SECTION ONE

INTRODUCTION

Judgment is the essential genome of leadership. Ultimately, a leader is judged by others on the performance of his or her organization. That performance is reliant on many factors; some are large—such as who to put in key jobs—while others are smaller—such as how to manage a product introduction or policy change. Each of these performance factors, whether big or small, requires judgment. That is, they demand that a leader use however much data is available to determine when to act and what to do.

This handbook deals with the big leadership judgments: people, strategy and crisis. These are the ones that determine leadership success or failure. While this handbook will help you apply the leadership judgment lessons discussed in the main text, it can also be treated as a stand-alone guide to improving your own judgment capabilities.

A DYNAMIC PROCESS

We make a distinction between judgment and decision making. Much of the academic literature and popular notions of decision making culminate in a single moment when the leader makes a decision. In this handbook, we focus on judgment as a process that unfolds over time. Analysis of this process has either been absent, leaving leaders to unconsciously pick a course of action, or has been unrealistically linear. In our experience, the judgment process is actually more like a drama with plotlines, characters, and sometimes unforeseen twists and turns. A leader’s success hinges on how well she manages the entire process, not just the single moment when a decision is made.

Key leadership judgments encompass several dimensions:

Time: We have identified three phases to the process. These phases do not always happen in a clean linear fashion; good leaders self-correct by using “redo loops,” repeating earlier phases to correct errors or adjust for oversights.

Preparation: What happens before the leader makes the decision.

The Call: What the leader does as he or she makes the decision that helps it turn out to be the right one.

Execution: What the leader must oversee to make sure the call produces the desired results.

Domain: We have identified three critical domains in which most of the most important calls are required:

Judgments about people

Judgments about strategy

Judgments in time of crisis

Constituencies: A leader’s relationships are the sources of the information needed to make a successful call. They also provide the means for executing the call, and represent the various interests that must be attended to throughout the process. A leader must interact with these different constituencies and manage those relationships to make successful calls. In addition, to improve judgment making throughout the organization, the leader must use these interactions to help others learn to make successful calls.

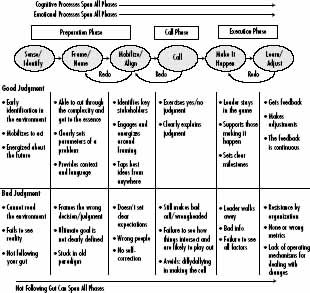

The diagram on the next page shows how these dimensions play out in the judgment process:

IT’S WHAT HAPPENS THAT COUNTS

A leader’s report card is ultimately a reflection of how he or she fared on the major judgments that impacted the well-being of the institution. The diagram on the next page lists factors that contribute to good or bad leadership judgment. The leader can make mistakes and still have a good judgment outcome by using the redo loops to continuously self-correct. The test of leadership is how well the leader adapts during the process to drive a successful outcome. There is no such thing as a strategy that’s good in theory but lousy in execution. A leader sets his or her organization on a course based on the premise that it will lead to success. Recognizing execution limitations during the judgment process is as vital as having intellectual clarity about a potential breakthrough strategy. Similarly, people judgments rest on whether people put in leadership positions are able to do the job with integrity and courage as they deliver results.

Bill George, former CEO of Medtronic and currently a Harvard professor, shared a story during an interview that encapsulated this sentiment. Reflecting on a wildly successful career that included growing the company from $1.1 billion in market capitalization to over $60 billion, and the market introduction of lifesaving technologies along the way, George shared what he called his “greatest failure.” Prior to his years at Medtronic, George had been a promising senior executive at Litton Industries. While there, for three years George actively groomed someone to ultimately be his replacement. “Every year I would present him as my successor and everyone said, ‘Yes, yes, yes!’” But when George left Litton, the CEO stepped in and selected a different production leader with less experience. George still blames himself for Litton’s poor performance and eventual closure after his own departure.

LEADERSHIP JUDGMENT PROCESS

George’s self-assessment is candid, honest, and, in our view, correct. His succession judgment was a failure. Although George’s succession candidate likely would have been better than the CEO’s choice—it’s hard to imagine much worse—George wasn’t able to make it happen. It would have been easy for George to let himself off the hook on this judgment call, even to have felt smug about the correctness of his analysis. After all, the CEO intervened and George had no real ability to campaign after he left the company. However, George holds himself accountable for his inability to get his people judgment implemented and realizes that the eventual closure of the business was related to that failure. In short, George knew long ago that the measure of a successful judgment isn’t how well-reasoned it is; only the outcome matters.

This doesn’t mean that a leader must make the right call on the first try. Rather, as the diagram on page 289 depicts, the leader can go back to earlier stages of the judgment call process to correct mistakes. We call these “redo” loops. This openness to learning and self-correction should not be mistaken for lack of commitment. As Bill George said of his many later successful judgments,

My style is I don’t second-guess myself…. I may be wrong and we may have to change it but I don’t say, ‘Why didn’t I do that’ or ‘Why did I go for that.’ You don’t know if something’s going to work until you go…. You just have to hang in there because you don’t know.

Another leader we interviewed, General Wayne Downing, the late four-star commander of the Special Operations Forces, described a “redo” loop he experienced on the battlefield. After a year and a half of planning, in 1989 a stealthy force was infiltrated into Panama to topple the illegal and corrupt regime of Manuel Noriega. Less than five hours before U.S. forces were prepared to strike, covert surveillance lost sight of the Panamanian leader. As Downing told us,

“We’re in a crisis, a major crisis…and the clock is ticking. We have the duly elected government under protection, which we planned to install as soon as we get Noriega and his regime out of there. Our forces are preparing to move to their attack positions as soon as it gets dark. The 75th Ranger Regiment and the 82nd Airborne Division were in the air flying down to jump in at 1 A.M. And we cannot find this guy.”

One response to the chaos of the situation would have been for General Downing to execute the plan as it had been rehearsed. This would have enabled the United States to stabilize the situation so that the elected government could have taken control. However, in the process Noriega likely would have eluded U.S. forces and escaped to Cuba or Venezuela. The long-term strength of the democratically elected Panamanian government would have been jeopardized. Downing described his team’s response:

It was me and my operations officers. We sat down and started peppering each other back and forth. In fifteen minutes, we turned that thing—changed something that we’d been working on for a year and a half—and changed it just like that because the situation had changed…. You’re prepared for this because on a battlefield the enemy always has a vote. You can have all these great plans, but you know things are going to change.

The new plan that Downing and his team came up with was to find the top 100 people that Noriega was associated with and from whom he would likely seek assistance. In the hours that followed the preplanned raids, U.S. forces found 95 of the top 100 people. As Downing recalled, “We dried up his support network to a point where he had to seek refuge with the Papal Nuncio, and then later surrendered to us.”

Downing’s story is a vivid example of a “redo” loop in action. Rather than hope his original plan would somehow still work and rather than completely abandon the mission, Downing created space for him and his team to deliberate, debate, and adjust.

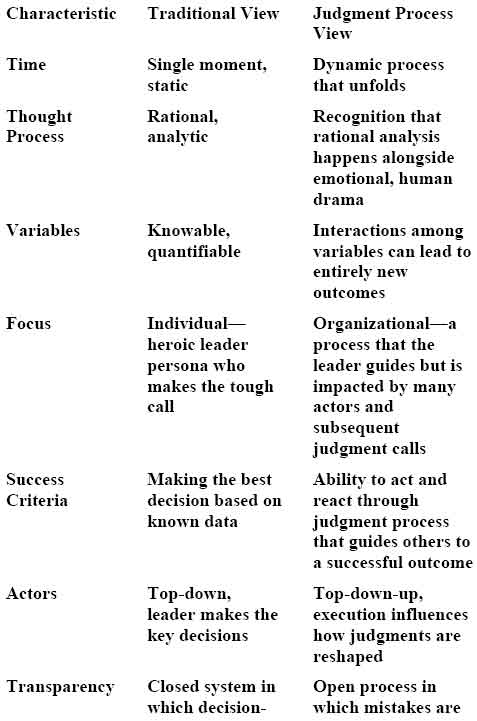

The following chart reflects some of the key differences between popular notions of decision-making and how we frame the judgment process:

DECISION MAKING AND FRAMING THE JUDGMENT PROCESS

JUDGMENT BUILT UPON DEEP KNOWLEDGE

Great leaders have a high percentage of good judgment calls. Every leader makes some bad judgments but great leaders learn from these and don’t repeat them. They manage the judgment process so that outcomes are successful while people are involved and developed along the way. Doing this requires the leader to have knowledge that spans beyond a “just the facts” analytical capability. It requires deeper knowledge in four areas:

- Self-Knowledge: Awareness of one’s personal values, goals, and aspirations. This includes recognition of when these personal desires may lead to a bias in sensing the need for a judgment or interpreting facts. It also includes the ability to create a mental storyline for how judgments will play out and the results they lead to.

- Social Network Knowledge: Understanding of the personalities, skills, and judgment track records of those on your team. This includes how they supplement or bias your judgment process.

- Organizational Knowledge: Knowing how people in the organization will respond, adapt, and execute. This also includes personal networks or mechanisms for learning from leaders at all levels in the organization.

- Contextual Knowledge: Understanding based on relationships and interactions with stakeholders such as customers, suppliers, government, investors, competitors, or interest groups that may impact the outcome of a judgment. This entails anticipating not only how they will respond directly to a judgment but how they will interact with one another throughout the judgment process.

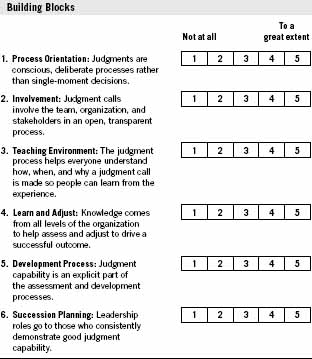

DEVELOPING JUDGMENT

Too often judgment is viewed as one of those ineffable leadership qualities that a person either has or doesn’t have. Obviously, judgment is built upon life experience. Most of us prefer the experienced doctor who has seen thousands of cases to the newly minted resident who will use our case to develop knowledge. Certainly, some people do seem to possess inherent leadership characteristics that enable the judgment process. To name only a few of these: they develop broader and deeper relationships, they empathize with others, they are future-oriented, or they have courage to act in the absence of full knowledge. Nonetheless, judgment is a capability that can be developed and improved when it becomes a conscious process.

This starts with the extent to which judgment as a capability is discussed and developed within your organization. Take the following test to assess where you stand:

Implications for my organization:

PLAN FOR THIS HANDBOOK

Now that you have reflected on the characteristics of successful leaders and the judgment processes they create, this handbook will help you to develop your leadership judgment capability. The organizing principle for the handbook is to examine the four bases of knowledge that lead to good judgment. Each section will focus on one of these and guide you through a series of exercises to assess your judgment and plan for improvement.

Section Two: Self-Knowledge

- Experiences that have shaped your judgment capability

- Evaluating your judgment track record

- Identifying your judgment pitfalls and development opportunities

Section Three: Self-Knowledge—Developing a Storyline

- Outlining your storyline

- Imagining alternate endings

- Knowing when you need to make judgments

Section Four: Your Team

- Evaluating your team’s judgment capability

- Recognizing how individuals affect judgment processes

- Building mechanisms for improving your team’s judgment process

Section Five: Organizational Knowledge

- Identifying your network for organizational knowledge creation

- Developing mechanisms for engaging the organization

- Judgment-building processes for all levels

Section Six: Contextual Knowledge

- Outlining your stakeholder network and relationships

- Determining when, where, and how to involve key stakeholders

- Developing processes that engage stakeholders

Section Seven: Make the Right Call

- Turning your learning into action