2

FRAMEWORK FOR LEADERSHIP JUDGMENT

Good Judgment Calls Are a Process, Not an Event

Good Judgment Calls Are a Process, Not an Event

- It starts with the leader recognizing a need and framing the call.

- It continues through execution and adjustment.

Leaders Must Make Calls in Three Critical Domains

Leaders Must Make Calls in Three Critical Domains

- Calls about people are the most difficult, and the most critical.

- Other key domains are strategy and crisis.

Exercising Good Judgment Requires Self-Knowledge

Exercising Good Judgment Requires Self-Knowledge

- It isn’t a solo performance; support teams are vital.

- Engaging others leads to success.

Fingerspitzengefühl.

It’s a word our late friend Wayne Downing used with us one day. Downing was the former head of the U.S. military’s Special Operations Forces and a retired four-star general.

“You have to have a sense for the situation…know when to act, and know what to do. You need fingerspitzengefühl,” he told us.

Fingerspitzengefühl. It’s a German term that is often translated as “sure instinct.” More literally, it’s about feeling through the tips of one’s fingers. You get it, Downing told us, from experience. He’s right. Experience is very important in developing judgment.

One of the reasons that we and other students of leadership haven’t written a lot about judgment is that it is a hard subject. It’s easier—and therefore tempting—to toss it off as one of those important but ineffable qualities. Downing wasn’t doing that. His comment came in the midst of a long, thoughtful conversation. But it brought to mind how often we do hear, and sometimes even think to ourselves, that judgment is largely about intuition. It’s about the je ne sais quoi of just sensing, having good antennae. There are things you know in your gut. Or you “blink” and have a wondrous, instantaneous epiphany.

These statements of nonrational “thinking” certainly do feel true, and it might be that in a sense they even are true. There is the moment, as Jeff Immelt puts it, when “Boom, I decide.” But to the extent that that is true, it is a shorthand description for a complex web of other thoughts and activity. It’s like saying that Duke beat Michigan at basketball because the Blue Devils scored more points. It may be true, but it is not very helpful to understanding how the Blue Devils came to outscore the Wolverines. What about the strategy, the practice, the timing, the training, and even the recruiting? As sports fans know, there’s a lot more to it.

And, as all of us know, there is a lot more to exercising good judgment as well. Good judgment is not one terrific aha moment after another. In the real world, good judgment, at least on the big issues that make a difference, is usually an incremental process. Quantum theory, the polio vaccine, cubism, the double helix, the iPod—all these landmark breakthroughs in business, science, engineering, and the arts came about only after years of trying and “trialing,” of mistakes and missteps, of correcting, refining, and, yes, trying again. Intuition helps; so does blinking, but it is rarely sufficient. As the Talmud says, expect miracles, but don’t count on them.

So, here goes. Having come face-to-face with our belief that good judgment is the essential genome of good leadership, we have tackled it head-on. We have come up with a framework for understanding how good leaders go about making good judgment calls.

All the usual caveats are present. We don’t pretend to have all the answers. We don’t even presume that we have asked all of the possible questions. But we have been around and watched hundreds of leaders making thousands of judgment calls. We have seen good calls and bad ones. We have seen leaders make so-so initial calls and then manage and retune them midair to produce brilliant results. And we have seen leaders make spot-on, inspired decisions and then end up in the ditch because they didn’t follow through on execution, or looked away at a key moment and missed a critical context change. We have seen, and learned, a lot. And, putting our brains and experience together, we have come up with our framework.

We offer it with two goals in mind. One is to help leaders working in the field not only to improve their own judgment-making faculties, but also to do a better, more intentional job of developing good judgment in others. The second goal is to encourage and influence a more vigorous public conversation about judgment. We need more leaders with better judgment. In the terms used in the process we describe below, we have “sensed and identified” the need for a keener focus on judgment. Now we are “naming and framing” the issue.

THE FRAMEWORK

Despite the implications of the word call, the judgment calls that leaders make cannot be viewed as single, point-in-time events. Like umpires and referees, leaders do, at some moment, make a call. They make a determination about how things should proceed. But unlike umpires and referees, they cannot—without risking total failure—quickly forget them and move ahead to the next play. Rather, for a leader, the moment of making the call comes in the middle of a process.

That process begins with the leader recognizing the need for a judgment and continues through successful execution. A leader is said to have “good judgment” when he or she repeatedly makes judgment calls that turn out well. These calls frequently turn out well because the leader has mastered a complex, constantly morphing process that unfolds in several dimensions. We have identified three phases to the process.

TIME

Pre: What happens before the leader makes the decision

The Call: What the leader does as he or she makes the decision that helps it turn out to be the right one

Execution: What the leader must oversee to make sure the call produces the desired results

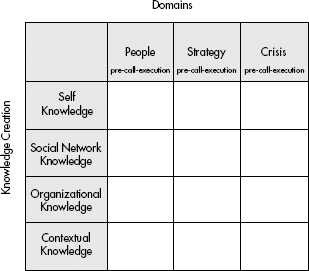

DOMAIN

The elements of the process, the attention that must be paid to each of them, and the time over which the judgment unfolds varies with its subject matter. We have identified three critical domains in which most of the most important calls are found:

judgments about people

judgments about strategy

judgments in time of crisis

CONSTITUENCIES

Leaders make the calls, but they do it in relation to the world around them. A leader’s relationships are the sources of the information needed to make a successful call. They also provide the means for executing the call and represent the various interests that must be attended to throughout the process. A leader must interact with these different constituencies and manage the relationships to make successful calls.

In addition, to improve judgment-making throughout the organization, the leader must use these interactions to help others learn to make successful calls. We have identified four different types of knowledge needed to do this.

SELF-KNOWLEDGE

How do you learn? Do you face reality? Do you watch and listen? Are you willing to improve?

SOCIAL NETWORK KNOWLEDGE

Do you know how to build a strong team? How do you teach your team to make better judgments?

ORGANIZATIONAL KNOWLEDGE

Do you know how to draw on the strengths of others throughout the organization? Can you create broad-scale processes for teaching them to make smart judgments?

CONTEXTUAL KNOWLEDGE

Do you know how to create smart interactions with the myriad other stakeholders, such as customers, suppliers, government, stockholders, competitors, and interest groups?

The Judgment Calls Matrix

JUDGMENT: the essence of effective leadership. It is a contextually informed decision-making process encompassing three domains: people, strategy, and crisis. Within each domain, leadership judgments follow a three-phase process: preparation, the call, and execution. Good leadership judgment is supported by contextual knowledge of one’s self, social network, organization, and stakeholders.

THE THREE JUDGMENT DOMAINS:

PEOPLE, STRATEGY, AND CRISIS

These are the three domains that make the most difference to the survival and well-being of any institution. If they are unattended to or if bad calls are made in these domains, it can be fatal to an organization.

1. People Judgment Calls

While misjudgments in any of the three domains have the potential to be fatal, the one with the most potential is people. If leaders don’t make smart judgment calls about the people on their teams, or if they manage them poorly, then there is no way they can set a sound direction and strategy for the enterprise, nor can they effectively deal with crises. The first priority is getting the right people on the team, and then setting the strategy and being ready for the inevitable crises.

The selection of Mark Hurd to succeed Carly Fiorina as CEO of Hewlett-Packard made all the difference. Almost without changing Fiorina’s strategic portfolio at all or changing her team, he turned her dismal failure into a roaring success. When Fiorina was fired in early 2005, her $19 billion acquisition of Compaq was considered a bad strategic judgment. The company was in disarray. HP’s stock price had declined 15 percent during a period when rival Dell’s shares had surged a remarkable 90 percent. Morale was terrible.

When Hurd walked in the door two months later, he immediately turned his attention to “rebuilding the foundation,” as he put it. Undoing the Compaq merger was not an option. But there was a rising clamor on Wall Street for a strategic shift. Spinning off the company’s marginally profitable PC business from its very profitable printer business was one often-discussed scenario. But Hurd judged that after years of turmoil, the people at HP didn’t need yet another new vision. What they needed was to buckle down and solve the thorny problems in the existing businesses.

Hurd’s philosophy of leadership and his personality couldn’t have been more different from Fiorina’s. She was a celebrity who viewed her role as being the highly visible poster girl for HP. She talked about her grand vision for the company in an interconnected world and jetted around the globe attending conferences and making speeches. But her look-at-me style and failure to deliver results alienated both employees and investors.

Hurd, who had previously been CEO of NCR, was a hands-on operations guy. He was immediately welcomed within HP because he seemed to be the “anti-Carly.” Unlike her, he avoided the limelight and focused all of his attention on fixing internal problems and pleasing customers. His unflashy style and no-nonsense approach were what allowed him to succeed where Fiorina failed. He laid off an additional fifteen thousand workers, on top of the twenty-six thousand that were let go after the Compaq merger. He reached outside the organization to bring in a few key executives and he made cost cutting a top priority. Under another leader, these could have been unpopular moves. But Hurd dug in and went to work alongside his new colleagues. He focused on the fundamentals and delivered on Fiorina’s promises where she could not. To be fair to Fiorina, Hurd got the benefit of her strategic judgments, including the company acquisition that finally started paying off.

At Merck, there were several serious failures in the people judgment category. One very questionable judgment was the hiring of Ray Gilmartin as CEO. He appears to have delayed and avoided facing up to the problems with the company’s Vioxx drug until a rising tide of evidence tying the drug to heart problems forced a multi-billion-dollar recall. There were over 86 million people using Vioxx in eighty countries. In planning for his anticipated retirement, Roy Vagelos, Merck CEO, who preceded Gilmartin as CEO, had begun grooming a successor, and in 1993 had named Richard Markham, chief operating officer, the heir apparent. But just months before Vagelos was to retire, Markham abruptly left for “personal reasons” and the Merck board began a frantic search for a successor.

Driven by the urgent need to replace Vagelos, who was approaching the mandatory retirement age, the board made a poor judgment call in Gilmartin. His background and job as CEO of Becton Dickinson, a much smaller company in the medical technology business, had not prepared him to lead a company of the size and complexity of Merck, nor did he have any experience in big pharma, a vastly different industry than medical technology.

Mark Hurd also joined Hewlett-Packard from a much smaller company, but NCR’s business was much more similar to HP’s than Becton Dickinson’s was to Merck’s. In fact, an HP board member said that the reason Hurd was chosen was that he demonstrated in his interviews that he had a deep understanding of HP and how it made money.

Once Gilmartin arrived, he was unable to build the sort of high-performance team he sorely needed. The deck was stacked against him in part because Vagelos, as a longtime Merck insider, a medical doctor, and former head of research at Merck, had been comfortable dealing with the scientific side of the business. Because he had expertise of his own, he was less dependent on his scientists and was able to make better judgments about their work. But Ray Gilmartin, who was not a research scientist, had to depend on others. And, as things turned out, he depended on the wrong people. He didn’t put together a team that gave him good information and wise counsel.

Carly Fiorina was similarly unprepared to head HP. Her previous career had been as a sales and marketing executive manager at AT&T and then Lucent Technologies, where she rose to group president of Lucent’s Global Service Provider business. She lacked the experience to lead a complex, multibusiness, high-tech multinational firm. Both Fiorina and Gilmartin did not exercise good judgment in people and did not put together strong collaborative teams to augment their own competencies.

People calls are often more complex and difficult to get right than other types of calls. They are more likely to be affected by the emotional attachments or dislikes of the leader, and they evoke emotional reactions in the people affected by the calls. People calls must be made while the actors in the drama are reacting to and shaping the judgment process as it is under way.

People calls are often viewed as win-lose decisions for various players in the organization, and as such they unleash the most powerful of political forces in an organization. In order to make good judgment calls, a leader must effectively manage these forces.

2. Strategy Judgment Calls

The Vioxx crisis was not the only problem at Merck on Gilmartin’s watch. He also made strategic mistakes that could, again, be traced back to people judgment. Before Gilmartin arrived, Merck had a history of going it alone and relying on its scientists to come up with big new drugs. It was a strategy that had served Merck well. But in the mid-nineties, as several promising products didn’t work out, the new-drug pipeline was nearly dry. Faced with a historically go-it-alone culture and without good guidance, Gilmartin didn’t recognize the severity of the problem, nor did he make the necessary changes to the company’s strategy.

The role of the leader is to lead the organization to success, so when the current strategic road isn’t leading toward success, it is his or her job to find a new path. How well a leader makes strategic judgment calls is a function of both (a) his or her own ability to look over the horizon and frame the right question and (b) the people with whom he or she chooses to interact.

In the case of Jack Welch, interactions with Peter Drucker had a powerful impact on his strategic thinking. Soon after he became CEO of General Electric, Welch had a meeting with Drucker. As they discussed GE’s various businesses, Drucker, Welch recounts, asked him at one point: “If you weren’t already in this business today, would you go into it?” It was a question that crystallized Welch’s thinking and ultimately resulted in his famous “#1, #2, fix, close, or sell strategy.”

It took Welch a while to arrive at the conclusion that the way GE was going to succeed was by having only businesses that were number one or number two in their industries. Other businesses that couldn’t be raised to one of those positions would be sold or closed. One prominent example was the sale of GE Housewares in 1984. The press derided Welch for selling off one of GE’s most visible businesses, but as a division increasingly under pressure from knockoffs coming from Asia, it was unquestionably the right move at the right time. Welch’s consultation with Peter Drucker started the process that helped him frame his strategic thinking in a new way. This judgment call radically altered the history of GE.

Over the course of his twenty-year tenure, Welch changed the content of his strategy for GE several times. But he never forgot Drucker’s fundamental question. In the late 1990s, a group of midlevel students at GE’s Crotonville leadership institute challenged him, saying that the “#1, #2, fix, close, or sell” strategy was hurting the company because executives were gaming the system.

They were deliberately defining their markets narrowly so that they could be number one or number two, and as a result, the company was missing opportunities. In response, Welch ordered that all business heads redefine their markets so that they had no more than a 10 percent share. And in the mid-1990s he redefined GE from a company that sold products to be a company that delivered services. It still manufactured many kinds of equipment and electrical machinery, but Welch’s new business model was, for example, to provide a hospital with an efficient radiology department, rather than just a good CAT scan or MRI. The machinery was only part of a package that included software and support to help the hospital get and remain operationally effective.

When Jeff Immelt succeeded Welch, he made judgment calls of his own about the strategy of GE. He decided it was time to transform the company into a technology growth company. He selected ten key technologies, such as nanotechnology and molecular imaging, and has made several acquisitions to execute this strategy, including the $10 billion Amersham acquisition.

Immelt says he believes making strategic judgment calls is how he adds value to the company. In the fall of 2004, he told a group of Michigan MBAs: “There’s more importance today on strategy, on picking businesses than ever before…. When you’re Chairman of GE, you spend a lot of time thinking about which businesses to pick, investing in health care, or investing in entertainment…. In the environment we’re in, good execution and good operations aren’t enough to fix a business with a flawed strategy. So you need to spend time understanding what businesses you think are going to work, what business models seem to make sense. Strategy is more important than ever before.”1

3. Crisis Judgment Calls

It’s obviously important for leaders to make good judgment calls in crisis situations because crises are by definition very dangerous moments. But errors at these times aren’t actually any more likely to be fatal than errors in judgment regarding people and strategy. The big difference is that they are usually time pressured and, as a result, any disastrous consequences brought on by bad calls at these moments often come very quickly.

It’s instructive to look at crisis calls, not only because getting them right is so important, but also because they compress and highlight so many of the important elements of making judgment calls. They require that a leader have clear values and know his or her ultimate goal. There must be open and effective communication among members of the senior team and throughout the ranks. There must be a good process for gathering and analyzing data. And there must be effective execution. These are the fundamental elements for making good judgment calls under any circumstances, but the added pressure of a crisis brings them more clearly into focus.

One organization that paradoxically handles crises as part of its regular routine is the military when it is at war. The leaders at all levels in the military deal with crises as a regular part of their role. The stakes are clearly different in business than in the military, but the urgency, the unpredictability, and the serious nature of the situations are the same. There are important lessons for business leaders to be found in reflecting on how the military handles crises.

Wayne Downing pointed out that the first thing you need to do in a crisis is keep your wits about you. Understand, as best you can, what you are facing, and then come up with the best strategy you can for accomplishing your ultimate goal in the given circumstances. First of all, you need to know what your strategic goal is. “It’s amazing to me how in crisis, sometimes people forget that one,” he said. “They will come up with a great solution but they will find that it has nothing to do with accomplishing what it is they are supposed to be doing. If you don’t stay focused on the mission, you drift into activity that is wasted.”

Crises are not restricted to military organizations. All organizations face crises at one time or another. Some are life-threatening to the institution, if not to human life. Crises not handled well, where good judgment calls were not made, can lead to the demise of an institution. The organizational crisis most taught to business students is the Johnson & Johnson (J&J) Tylenol case, where poison was found in bottles of the product on store shelves. The CEO at the time, Jim Burke, did a masterful job of pulling the product, assuring all employees and consumers that they were taking quick action to deal with the crisis, and ultimately won the consumers back to the product. Burke made great on-the-fly judgment calls in that crisis. They were guided by the J&J credo that puts the customer first.

CHAMBERS AT CISCO

A much more complex crisis than Tylenol, one that threatened the total organization’s future, was the stock-price crash Cisco faced in early 2001. Cisco, led by CEO John Chambers, was at the top, literally. For a couple of days its market cap was number one in the world, bigger than GE at $531 billion (GE was $520 in March 2000). Then in early 2001 the crash occurred in the industry and the near-death Cisco crisis. As Chambers said, “If somebody would’ve told me that we’d go from 70 percent growth to minus 30 percent growth in forty-five days, I’d have said it was mathematically impossible. The company was in a free fall.”2

At its peak in 2000 its stock was over $80 a share. When it finally bottomed out, it hit $9.42 in late 2002 (at its peak it was performing 250% above the S&P average, at its lowest it was 50% below). Never in the history of business has a company gone from number one to such depths and then had a comeback, all under the leadership of the same CEO. In mid-2007 the stock had rebounded and was around $28 per share with a market capitalization of $170 billion. In contrast, the IBM crisis under John Akers in the early 1990s was triggered by the market capitalization going from close to $100 billion to below $38 billion. In the IBM case it resulted in Akers being fired and the board going outside for the turnaround CEO, namely, Lou Gerstner.

Chambers’s crisis judgments set the stage for one of the most unique turnaround stories in business history, made even more amazing because the leader who was at the helm when the company went off the cliff is the same one who made the judgments to transform and revitalize the company.

He can be faulted for not originally sensing and identifying the need for dealing with the crisis earlier, because there were those inside the company and outside who saw some of the signals. Once the crisis hit, Chambers was quick on the trigger to frame and name the judgments that had to be made. The result: deep staff cuts, 8,500 or 18 percent of the workforce, stopping all acquisitions, changing how the company worked together, breaking down silos, stopping the free-spending culture, and setting the stage for a new strategic direction for the company. Chambers says that “after fifty-one days we were already focused on the upside.”3 This was when all the IR [information retrieval] competitors, such as Lucent, Nortel, and 3Com, floundered for several years.

Unlike Burke’s Tylenol crisis, a great example of crisis judgment to save a brand and the reputation of J&J, Chambers’s crisis judgment was about saving a company and resulted in major people judgments for who would lead various elements of the company. New strategy judgments were also required to get out of the crisis. There has been a totally new Cisco created out of the crisis. Cisco was not only freshly imagined but re-created. J&J got one of its many brands and its sterling reputation.

THE PROCESS OF JUDGMENT CALLS:

PREPARATION, CALL, EXECUTION

In all three of our domains, people, strategy, and crisis, good judgment calls always involve a process that starts with recognizing the need for the call and continues through to successful execution.

Understanding that a judgment call is a complex flow of events rather than a single, one-point event leads to the inevitable recognition that adjustments can be made throughout the process. There are points when irrevocable actions are taken. A bomb is dropped. A business is sold. A key leader is fired. An opportunity is missed.

Once JPMorgan Chase acquired Banc One, there was no turning back. But there are myriad opportunities along the way to make adjustments to the execution. That merger decision will turn out to be a good or bad judgment call over time, as the execution phase produces either continuous improvement or value destruction. It will depend on the quality of the judgment calls of Jamie Dimon and the team at JPMorgan Chase as they sort out strategy, make key people decisions, and deal with crises along the way.

Another implication of viewing judgment calls as flows rather than single events is that there are also myriad opportunities to mess it up. Carly Fiorina may have made a good strategy judgment when she decided that HP should acquire Compaq in 2001. But her efforts were doomed by flaws in the execution phase. By failing in the execution part of the process, she wasn’t able to implement the merger effectively and reap the benefits. So by our definition, Fiorina’s acquisition of Compaq was a bad judgment call. The fact that Mark Hurd, Fiorina’s successor as CEO of HP, was able to make a success of the merger doesn’t change the fact that Fiorina’s judgment call didn’t work out. Hurd simply made some new and better judgment calls after he took over.

Unlike Fiorina, who recognized the need to make a call but messed up the execution, the leaders at the old AT&T, Westinghouse, and GM (General Motors) failed at the beginning of the process. They succumbed to the boiled frog phenomenon. Like the frog that sits in the pan and doesn’t jump out if the water is heated slowly enough, they didn’t react quickly or aggressively enough to changes in their competitive environments. They saw the ongoing changes in their industries as only incremental, so they waited until their companies were nearly dead before they took action.

Andy Grove, whose career is a record of great judgment calls, illustrates the opposite of the boiled frog phenomenon. Like many people who are known for their good judgment, he is always scanning the horizon and looking for important change. In his book Only the Paranoid Survive: How to Identify and Exploit the Crisis Points That Challenge Every Business,4 the former CEO who led Intel through the tumultuous early years of the computer industry focuses on what he calls strategic inflection points. A SIP is a ten-times force—a change of such magnitude that it is at least ten times stronger than any that preceded it. He explains that leaders must recognize the moments when fundamental changes are occurring and act swiftly and decisively. Framing the issue and mobilizing the troops when there are only the slightest bits of change in the air are what has kept Intel at the top of its game.

Good judgment depends on how you think as much as what you know. It requires intelligence and values. It depends on the ability to gather information and to process it. It draws on experience and knowledge. The ability to shape and guide the judgment process plays out in the context of a lifetime of learning. But when things go wrong, it is often because the leader has stumbled on the fundamentals.

The Preparation Phase

SENSING AND IDENTIFYING THE NEED FOR A JUDGMENT CALL

As simple as this one seems, as Barbara Tuchman pointed out in The March of Folly: From Troy to Vietnam,5 failure to face reality and see the need to change has often had disastrous consequences. In the business world the demise of U.S. steel companies and of high-tech firms like Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) and Compaq, as well as the disastrous decline of the U.S. auto companies, attest to the difficulty of recognizing the need to make tough judgment calls. This was Andy Grove’s great strength and Ken Olsen’s great weakness. Olsen, as head of the Digital team, could have led the transformation of the computer and information technology industry, but instead allowed Digital to be lolled into complacency.

Sensing the need for a judgment call varies in each of the domains. For people judgment calls, identifying the need for a call isn’t really about whether something is going to happen, but rather when. Every CEO, every person in every job is going to leave it some day. Replacements will be needed. Nevertheless, an incredible number of otherwise highly regarded companies aren’t ready when it comes time to name a new CEO.

There is nothing more important to an institution than who is going to be its leader. Good people judgment calls require that it be the most important agenda. Yet the last decade has seen Merck, HP, 3M, Boeing, Kodak, Motorola, AT&T (sold to SBC, which salvaged the brand to rename SBC to AT&T), and many others having to bring in outsiders as CEO. What were these companies’ leaders doing ten years before the CEO crisis? One of the things they were not doing was identifying the need to develop strong leaders.

The companies that have developed internal CEO candidates and done well, such as GE, Pepsi, Intel, and P&G, have developed leadership pipelines, which, among other things, support making good judgment calls.

The other side of people judgment calls is letting go of the people who shouldn’t be around. This weeding-out test is one that many leaders fail, and often the failure starts with an emotional unwillingness to see the need. Facing reality around difficult issues is one of the hardest things a leader has to do. And the reality of having to fire people, especially ones who you know, and perhaps like, is one of the hardest-to-face realities of all.

This is because leaders are human. We all have blinders. We get attached to people. We distort the facts. We look the other way. Our experience is that contrary to what you might expect, the more senior-level leaders seem to have a tougher time with this than people lower down in the organization. How could the late Ken Lay not have fired Jeff Skilling and Andy Fastow at Enron? If we assume that Ken was not an out-and-out crook, which we can’t, then he made a very bad judgment call leaving these people on his team. As extreme as the Enron example is, it is not all that rare.

For strategy judgments, as we have already noted, scanning the horizon and identifying the need to make a judgment early are extremely helpful. The best prescription for helping leaders recognize the need for strategic judgment calls is captured by Andy Grove’s view that you must look over the horizon at tomorrow’s environment, be paranoid, and reinvent the organization. It’s hard to do this all the time. It requires discipline and a constant searching. There have been all kinds of examples throughout history of leaders not recognizing the need for strategic judgment calls. The legendary economist Joseph Schumpeter (1883–1950) pointed out that most new industries do not grow organically from those in the industry because they can’t see the need for change. Think the telegraph to telephones, railroads to automobiles, IBM hardware to Microsoft software.

Great leaders are always asking Peter Drucker’s questions about what businesses are good for today and which ones will be good for tomorrow. Drucker was all about “purposeful abandonment,” leaving behind what no longer worked while developing the breadwinners of tomorrow. A new environment often requires a new business theory. As the saying goes: “What brought you here won’t get you there.” Good strategy judgments usually start well before the need becomes obvious.

Many crises present themselves with such alarm-clanging ferocity that it is impossible to miss them. But others are more subtle. Sensing and identifying the need for a judgment call is what leadership at Merck did poorly. The leaders at Merck had plenty of data to have identified the Vioxx crisis long before its recall and the lawsuits started to pile up.

Two processes are required by the leader. One is cognitive: the ability to distinguish the important signals from the unimportant. The other is emotional: having the guts to face that something is indeed a crisis. Jack Welch always looked for leaders who had both qualities, but particularly the latter—the ability to make the really tough calls. Those who did not shy away from the most difficult decisions had what he called “edge.” They knew when to say yes or no and avoid the maybes.

FRAMING AND NAMING THE JUDGMENT CALL

Once there is recognition that a judgment call is required, a leader has to frame it and name it. Framing can drive the whole process. The “power of the first draft” is a phrase Noel picked up from a CEO in the 1970s. The point he was making is that there is tremendous power in framing issues, and then giving them a name. For Jack Welch and GE, in the 1990s Welch wanted to get his business leaders to grow more services to offset the pressures on product pricing. He framed and named the GE strategy as “We are a service company with competitive products, not a product company with services on the side.”

Best Buy had succeeded historically as a product-centric, big-box consumer electronics retailer selling the same products in all 675-plus stores regardless of the demographics of the location. Brad Anderson, the CEO who took the reins in 2002, and his leadership team framed and named the judgment as becoming “customer-centric,” that is, understanding the value propositions for segments of customers and then being able to tailor product and service offerings to fit their individual needs.

There is a vast social psychology literature on “framing” and how people’s cognitive maps make sense of the world around them. These are often referred to as mental models, and creative leaders use them to get people thinking about problems in ways that will be productive.

At Hewlett-Packard Mark Hurd framed the judgment he had to make when he arrived as “how to make the current portfolio of businesses succeed.” “Our portfolio of businesses has yet to prove its full value—not due to issues with the strategy, but rather due to the execution of the strategy,”6 he told investors in his first annual report letter. As a result, he focused on improving performance in those businesses. Had he framed the problem differently, as “What businesses do we want to be in?” he would have set about gathering data differently, and the answer would almost certainly have resulted in a realignment of the portfolio.

When Lou Gerstner took over IBM in the early 1990s, Big Blue was in big trouble, about to report its biggest loss ever, $8.1 billion. The company had missed the personal computer revolution, and arrogance and insularity had taken its toll on the once vaunted computer maker. Gerstner framed the judgment he had to make as follows: “In the spring of 1993, a big part of what I had to do was get the company refocused on the marketplace as the only valid measure of success. I started telling virtually every audience…that there was a customer running IBM, and that we are going to rebuild the company from the customer back.”7 Gerstner of course executed one of the great turnaround stories of modern-day business, turning an $8 billion-plus loss into a $5 billion gain in five years.

The mistake that most people make in framing crisis judgments is being too short-term. Almost by definition, there is great time pressure in a crisis, but a short-term fix uses up resources and is often not productive in getting toward the ultimate goal. “What should drive you in a crisis is your mission,” General Downing said. “In business that mission is carrying out your business strategy. You’ve got to accomplish the mission. You can drift off into activity that is gonna make you feel good, but if that activity is not ultimately accomplishing what your mission is, then it’s wasted and you’re going to have to go back and do it anyway.”

Ray Gilmartin never framed the Vioxx crisis appropriately. This failing compounded the series of failed judgment calls that threatens the survival of Merck.

MOBILIZING AND ALIGNING THE RIGHT PEOPLE

It is essential to get the people who have something to contribute on your team and into the game at the right moment while keeping all others out. Sometimes it means skipping over layers of the organization. Sometimes it means reaching out to unexpected places. It’s a tricky art to figure out how many people you need and who they are. You need to engage the right brains and experience, but also the right personalities and dynamics. You don’t want groupthink, but carpers, complainers, and footdraggers are no help either.

A poignant example of how bad judgments happen took place in GE Appliances’s business. It resulted in a $1 billion compressor fiasco in the 1980s.

In the early 1980s Appliances borrowed an idea previously used in small air conditioners. GE Appliances’ engineers designed an advanced rotary compressor to cool its refrigerators. Compared to GE’s existing compressors, it would require one-third the parts, half the manufacturing cost, and far less energy to operate. There were many risks: the technology required parts manufactured to tolerances of as little as one one-hundredth the width of a human hair, and the cost included a $120 million investment in a new automated factory. After much agonizing with executives from Appliances, Jack Welch approved the plan to make the new compressors instead of buying them. This turned out to be a bad judgment.

When the new refrigerators appeared in 1986, people bought so many that GE’s market share rose two percentage points. The rotary compressors represented breakthrough engineering. Then, in 1987, rotary-compressor refrigerators began to break down. The GE engineers found that certain critical parts were far less durable than expected and very difficult to repair. Welch made another judgment call: replace all of them with conventional compressors purchased from other manufacturers. In his 1988 annual report letter to shareholders he wrote, “Our aim is to come out of this situation with our reputation for customer support and satisfaction not only intact but—if anything—enhanced.”

In hindsight, the judgment process was flawed. The right people, whose mobilization and alignment could have changed the judgment, were left out of the loop. There were engineers who wanted to express their concerns. The layers of bureaucracy stifled these voices from being heard. Welch reflected on why that type of bad judgment happened and concluded, “With all the layers of approval we had then, no one had ownership of the decision. Ownership is essential.” That judgment cost the organization’s finances and reputation. This lesson and other, similar lessons strongly influenced Welch’s maniacal attack on hierarchy in GE so that, in his words, the organization should be “ventilated and free” of oppressive layers. Getting the right people influencing key judgments with firsthand knowledge was the goal.

The aligning part of the equation means getting on board not only the people who can help you make a smart decision and get it executed, but also the people who can derail it. One of the biggest mistakes we have seen leaders make time and time again is to underestimate the power of resisters and ambitious plotters. At Ford this cost Jac Nasser his job. When the Firestone tire crisis hit, there were Ford Explorer rollovers causing accidents and deaths. Nasser, quite rightly, spent the majority of his time personally leading the response to the crisis. By not having a trustworthy team, several formed a coalition to plot against him while he was dealing with the crisis. Leaders should always consider the opposition and manage the politics.

The Call Phase: Making the Judgment Call

Jeff Immelt’s “Boom, I make the decision” comes after he has gotten all the input. There is a moment when, based on his view of the time horizon for the judgment and sufficiency of input and involvement, the leader makes the call. Wayne Downing described a similar process when he was leading troops in battle. The judgment call for strategic direction of the company is often embedded in a stream of activity, such as Jeff Immelt’s GE strategy, which took several years to work through. The seeds were in his mind and part of the conversation among senior leaders at GE as early as 2001. Since then a series of judgment calls have resulted in shaping the strategic direction of GE.

The Execution Phase: Action—Make It Happen

Larry Bossidy, the retired CEO of Honeywell who coauthored a book called Execution: The Discipline of Getting Things Done,8 says that “thinking does not matter if nothing happens. There are too many people with bumble bee mentality who can’t make things happen.” Execution is a critical part of the exercise of good judgment. Once a clear call is made, then resources, people, capital, information, and technology must mobilized to support it. If they aren’t, the decision doesn’t get carried out and any good preparation and decision making simply goes down the tubes. By our definition, good judgment calls always produce good results.

When Brad Anderson and his leadership team at Best Buy made the judgment call in 2002 that Best Buy needed to be transformed into a customer-centric enterprise, he began a process that would take years of focus and effort. Once the call was made, he mobilized several senior-level action learning task forces to spend six months finding the segments in the Best Buy customer base that the company would cultivate. Next came selecting from among those leaders the people who would head up the segments, selecting the stores to be transformed, and mobilizing all the support functions to execute the new strategy. The whole execution process continues to play out in 2007 and will probably never be over.

Learn and Adjust: Continuous Adjustment

Because judgment calls are determined to be good or bad by their results, there is almost always time to make adjustments. Leadership judgment is a process; the final outcome can sometimes be dramatically altered in the execution phase. One example is Jack Welch’s judgment call to acquire Honeywell for $41 billion in October 2000. At the time this was seen as a brilliant move and a capstone to Welch’s twenty-year run at GE. The call was vintage Welch. GE and Welch knew Honeywell (AlliedSignal had acquired Honeywell and taken the name) and its businesses in depth and had them on GE’s acquisition radar screen for years. Welch exercised what we call “planful opportunism.” The planning work (“our preparation phase”) of judgment, of understanding Honeywell, was done in depth at GE. The opportunism part was Welch jumping on the “opportunity” when he saw that GE’s competitor, United Technology, was also going after Honeywell. He made the call and made it fast. There were two important reasons to make the call. One was to prevent United Technology from getting the acquisition, the other was acquiring the businesses of Honeywell for GE’s benefit. Both were strategically important. He made another call as well: he requested the GE board delay his retirement date so that the new CEO would not be burdened and potentially overwhelmed with the acquisition challenges.

As the judgment process unfolded in the execution phase, Welch had an opportunity to exercise one of his leadership precepts, to “face reality as it is, not as it was, or as you wish it were.” Following the U.S. Justice Department giving its blessing to this huge deal, GE and Honeywell notified the European Commission (ruling on antitrust issues) for its clearance. This left the final part of Welch’s judgment (“our execution phase”) in the hands of the European Commission. The new reality for Welch and GE occurred in June and July of 2001, when GE was told that the European Commission rejected the proposed acquisition. The European competition commissioner, Mario Monti, said at the time, “I regret that the companies were not able to agree on a solution that would have met the Commission’s competition concerns…. The European Commission and the U.S. Department of Justice have worked in close cooperation during this investigation. It is unfortunate that, in the end, we reached different conclusions.”9

In June 2001 GE made a number of proposals to the Commission to deal with the competition problems they had identified. The packages that GE proposed were all rejected because the Commission did not view them as resolving the problems they had identified. On July 3 the European Commission formally rejected the merger. The new reality, a rejection from the Commission, plus a greater risk due to an economic downturn, led to a good judgment by Welch, backed by new CEO Jeff Immelt, to walk away from the deal.

Was the attempted Honeywell acquisition a good or a bad call? This is an interesting question, as it can be looked at as both. The preparation phase of going after Honeywell qualifies as a good judgment, given all the information at hand. Where there is room for argument around good or bad judgment is in the execution phase. Should Welch and his team have done a better job of anticipating the EC resistance? We will never know that answer. But given twenty-twenty hindsight, we can say that the final Honeywell judgment was a good one. For one thing, GE could walk away without having to pay Honeywell a huge merger breakup penalty. For another, Immelt did not have to deal with a huge merger deal on top of filling Welch’s sizable shoes. All things considered, the outcome was good for the organization.

RESOURCES AND CONSTITUENCIES

The quality of a person’s judgment depends to a large degree on his or her ability to marshal resources and to interact well with the appropriate constituencies. Most of the time the resources and the interested constituencies overlap. A good leader uses four types of knowledge to make judgment calls.

Self-knowledge

Do you know who you are? Do you have clear values about what you are trying to accomplish? Do you have clear values about what you will and will not do to achieve your goals? Do you know what you know and what you don’t know? Can you empathize with others and anticipate their possible responses? Can you draw on your own experiences for future guidance? Are you willing to learn? Leaders who exercise good judgment calls are able to listen, reframe their thinking, and give up old paradigms. Jeff Immelt says, “It is an intense journey into yourself.”10 You are always looking for ways of doing it better, willing to break it and make it better.

Social Network Knowledge

In the language of social psychology, a person’s social network is a map of all of the relevant ties between the nodes being studied. The network can also be used to determine the social capital of individual actors. These concepts are often displayed in a social network diagram, where nodes are the points and ties are the lines. But we are using it here to mean the people you interact with and rely on most to help you achieve your corporate goals. Leadership is a team sport; there must be alignment of the leader’s team, the organization, and critical stakeholders to create the ongoing capacity for good judgment calls. The leader must consciously work to encourage teamwork, draw on the best resources of each individual, and help them learn to make better judgments in their own areas of responsibility.

Organizational Knowledge

Good leaders work hard to continuously enhance the team, organizational, and stakeholder capacity at all levels to make good judgment calls. Brad Anderson, CEO of Best Buy, and his leadership team are building a customer-centric organization at all levels. The effort is designed to enable store-level associates to participate in strategic judgment calls, as they go from a product-centric, one-size-fits-all business model to one that differentiates store merchandise and marketing according to the customer demographics in the area. It is not a static model; the store personnel are trained to continuously adjust the strategy based on day-to-day learning and teaching. The process not only keeps strategy on target, but also keeps improving the capacity of store associates to make good judgment calls. One example of the many we will explore later involved a twenty-year-old associate in the Westminster store in California. He spoke with us about his area of the store, plasma televisions. He told us: “I have really good news. I made the judgment call to change the physical display, widening the aisles, making the products stand out more. It has been great, my sales are significantly improving as measured by the store’s daily P&L, but I also made a mistake that I have to fix real fast. I have too much inventory stacked up in the store. My ROIC [return on invested capital] is going down; I need to get rid of the inventory fast.”

Reflect on this for a moment. In the old Best Buy the associate would never have been given the freedom or the tools to make the judgment call about the plasma TV area. Those decisions were centralized, all dictated by standardization from headquarters. All Best Buy stores looked the same and had the same products. The associate also would not have had any training to understand the financials and customer centricity. The Westminster associate has been equipped to make good judgment calls and to continuously adjust them based on data and commitment to the judgment call Brad Anderson and his top team made to implement a customer-centric strategy.

Stakeholder Knowledge

Engaging customers, suppliers, the community, and boards in generating knowledge to support better judgments is the final category. When GE started running Work-Out sessions with suppliers, it was a way to engage them in the generation of knowledge to feed better judgments. Work-Out was the name GE had given to the town hall meetings it began to implement with all of its employees and many of its suppliers, in which problems were literally “worked out” of the company. One such session in Medical Systems focused around building better MRI and CAT scan products, and included low-level teams from GE, low-tech metal cabinet producers, Kodak, and 3M as imaging materials producers, as well as small high-tech component makers.

In one workshop we had six supplier teams of six or seven members along with about twenty GE Medical Systems managers. The focus was on how to improve quality and productivity together in order to make better strategic judgments around the products. By spending three days in a workshop, the groups developed a common Teachable Point of View regarding their collective work and also worked out a lot of the human dynamic problems, conflicts, and unnecessary secrecy, thus building a stakeholder team that improved performance.

Engaging customers with the organization is another way to generate new stakeholder knowledge. At Intuit, the call centers work with customers—accountants who pay a fee for help in using the Intuit tax software with the accountants’ clients. The role of the Intuit call center associate is to support the accountant in making better judgments for their clients. A database has been developed at Intuit to capture and share best practices and generate new customer knowledge to support better and better judgments.

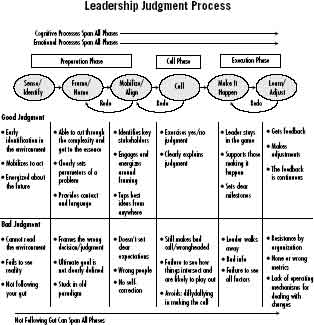

A FRAMEWORK FOR GOOD AND BAD JUDGMENTS

The chart “Leadership Judgment Process” lays out the phases of a judgment with the leadership behaviors, good and bad, that impact the outcome of judgments. No leader is perfect in all of the behaviors. When mistakes are made due to bypassing a step, good leaders recover by looping back. A. G. Lafley, CEO of P&G, for example, once left out a good mobilizing and aligning process and had to loop back with his top team to get them aligned, even though he had made an initial judgment call. David Novak, CEO of Yum! Brands, had to go back in the process after he launched the multibranding strategy, having two stores in one store, for example, half KFC (Kentucky Fried Chicken) and half Taco Bell. He made the judgment, but his team was not at all aligned and not fully supportive of executing the strategic judgment.

REDO LOOP

The judgment process is not simply a linear process; the leader is managing a process that can include mistakes and facts gleaned along the way, with plenty of opportunities to recover. In programming there are “redo loops”; in Perl and other computer languages, redo “starts this loop iteration over again.” We are using the term to underscore the importance of leaders self-correcting when they see a need to revisit and revise parts of the process.

Later in the book we will see how A. G. Lafley, CEO of P&G, created a “redo loop” in naming a CEO for one of the businesses because he did not have his vice chairmen and other senior executives mobilized and aligned. He did a redo that set the stage for a good judgment. David Novak had to do a redo in the execution of his multibranding of stores strategy judgment, which would have failed had he not slowed down the process, learned, and adjusted to make sure the judgment got executed. Welch’s Honeywell judgment process included a big redo loop during the execution phase, one that dramatically altered the outcome that started out as an acquisition of Honeywell but ended up as walking away from the deal. GE did not acquire Honeywell, but neither did United Technology.

We have begun to lay out our framework for leadership judgment calls. It is based on our premise that there is nothing more important in leadership than having the right people on the team who are able to set and execute the strategy and are capable of handling crises as they occur.

Great leaders not only make more important good judgment calls; they also take on the responsibility to develop the next generation of leaders with the capacity to make good judgment calls. They win today while very consciously building the team for tomorrow.

Furthermore, judgment is a process, not a “blink,” as Malcolm Gladwell argues in his book Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking11 where he postulates, “When experts make decisions they don’t logically compare all the options. They size up a situation immediately and act.” We are more aligned with Jerome Groopman’s How Doctors Think12 analysis, which takes a counter position, namely, “Relying too heavily on intuition has its perils. Cogent medical judgments meld first impressions with deliberate analysis.”

Blink and How Doctors Think both wrestle with judgment by “experts,” not leaders, making organizational judgments. The judgments we are dealing with are ones that impact the total institution and involve others both in making the judgment and in executing it.

When Jeff Immelt, CEO of GE, makes a strategic judgment to invest billions in new technologies, he does not make a “blink” judgment. When he describes the process, he says that he “wallows” in the preparation phase, which for some strategic judgments can be more than a year. At the point he feels he has done sufficient framing/ naming, mobilizing, and aligning, he does take that existential and intuitive leap, making the judgment call.

He then spends years ensuring that the judgment execution occurs. Otherwise, as a leader, his good “call” could turn into a bad judgment in the execution phase. Immelt is able to use the “redo loop” to ensure the success of the judgment process.