3

HAVING A STORYLINE

Winning Leaders Use Mental Frameworks to Guide Good Judgment

Winning Leaders Use Mental Frameworks to Guide Good Judgment

- Teachable Points of View set direction and behavioral values.

- Narrative storylines animate the future scenario.

The Most Successful Storylines Are Compelling and Practical

The Most Successful Storylines Are Compelling and Practical

- They connect disparate elements in an unfolding stream of events.

- They enable leaders to deal with scale, complexity, and uncertainty.

Storylines Are Organic: They Evolve in Response to Changing Circumstances

Storylines Are Organic: They Evolve in Response to Changing Circumstances

- Leaders plug in options to test possible outcomes.

- Storylines provide the platform for subplots at all levels of the organization.

One year after being named CEO of Boeing, Jim McNerney was in front of the world testifying to the Senate’s Armed Services Committee about Boeing’s settlement with the Justice Department of serious legal allegations. He told the committee and the world at large:

I hope to discuss why, going forward, the Congress and the taxpayers of this country can place their trust in Boeing. Companies doing business with the U.S. government are expected to adhere to the highest legal and ethical standards. I acknowledge that Boeing did not live up to those expectations.1

This framed one of McNerney’s biggest leadership judgments since taking over as CEO of Boeing in July 2005. Boeing’s 2006 agreement to pay $615 million put an end to three years of Justice Department investigations into alleged improper behavior on the part of several Boeing employees, including two senior executives. Boeing’s settlement with the Justice Department allowed the company to avoid criminal charges or admission of wrongdoing. It was the largest financial settlement agreed to by a defense contractor for alleged wrongdoing. The Wall Street Journal summarized the story, saying that Boeing was charged with:

[I]mproperly acquiring thousands of pages of rival Lockheed Martin Corp’s proprietary documents in the late 1990s, using some of them to help win a competition for government rocket-launching business.

Years later, Boeing illegally recruited a senior Air Force procurement official while she still had authority over billions of dollars in other Boeing contracts. She also championed company efforts to skirt normal procurement procedures in offering to provide refueling takers to the Air Force through a controversial $20 billion leasing program.

The uproar led to the firing of Boeing Chief Financial Officer Michael Sears in 2003 and the resignation of Chairman Phil Condit. The flurry of Justice Department and congressional investigations expose the most sweeping Pentagon procurement scandal since the end of the Cold War.

Mr. Sears, as well as Darleen Druyun, the former Air Force official served time in federal prisons.2

This was pretty tough stuff for the new CEO to take on during his first year. Weeks later, on August 1, McNerney went before the public in a Senate committee hearing to defend Boeing and his first high-profile crisis judgments at the company’s helm. Senator John Warner opened the Armed Services Committee hearing on the Boeing Company’s Global Settlement Agreement with the following statement:

We meet today to discuss the results of two Department of Justice investigations of the Boeing Company, both begun three years ago, into the allegations of improper use of proprietary information obtained from a competitor to compete for launch services contracts under the Air Force’s Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle Program and an investigation of the circumstances surrounding the hiring of Ms. Darlene Druyan, a senior Air Force official, by Boeing.3

McNerney joined a once proud company with a very tarnished image facing very serious allegations. He was a board member prior to becoming CEO, so he was fully aware of the crisis he was inheriting. Three important leadership judgments at Boeing led up to his personal role in moving the crisis to a conclusion. The first two were people judgments by the board: the first was forcing the resignation of the previous CEO, Harry Stonecipher; the second was to appoint Jim McNerney, then CEO of 3M, to be the new CEO.

The third leadership judgment was for McNerney to involve himself deeply and directly in resolving the crisis that he inherited. He could have fought the allegations and dragged out the discussions; he could have underplayed the importance of the matter and blamed former leaders. Instead, he made a judgment that turned the crisis into an opportunity to transform Boeing’s internal culture and leadership behaviors so that the new DNA was one that supported his strategy for Boeing to be a world-class model of competitiveness and ethical leadership. He also saw an important opportunity with the settlement to further the restoration of Boeing’s tarnished public image and brand. He described the crisis in the following terms:

[T]he events, themselves, have caused an immense amount of introspection at Boeing. How could a company with a history of reliability and self-image of unquestioned integrity have made these mistakes? This introspection set a course of building one of the most robust ethics and compliance programs in corporate America. That is the lasting legacy—and silver lining—of this dark cloud in our history.4

McNerney Becomes Boeing’s Third CEO in Three Years

McNerney had been one of three finalists to succeed Jack Welch as CEO of General Electric in 2001. When that job went to Jeffrey Immelt, McNerney had gone to become chairman of 3M in Minneapolis. When first mentioned for the Boeing job in early 2005, McNerney had taken himself out of the running. He had been at 3M only four years. He had brought new energy and fiscal discipline to the struggling manufacturer. The company’s earnings and stock performance had rebounded for a gain of 45 percent, and he had begun developing new strong leaders to take the company into the future. He said he liked his work at 3M and he didn’t want to leave.

But aerospace was too exciting for McNerney to turn down. In the late 1990s he had headed GE’s Aircraft Engines business and helped it grow into the leading force in the industry. He had worked with Boeing as a supplier selling engines to customers buying Boeing planes. He had joined the Boeing board in 2001. So he knew a lot of people in the company and the industry, as well as a lot about its business. He had a passion for it, and when he thought of where he would like to end his career he realized that he had to seriously consider Boeing. He changed his mind and made a crucial judgment call to accept the job as Boeing CEO, he said, because the opportunity probably wouldn’t come around again, and he really wanted to do it.

After Condit’s sudden departure, the board had called Harry Stonecipher back from retirement. Stonecipher, a widely respected former Boeing president, stepped into the crisis and began to make good progress toward cleaning house. Then embarrassing e-mails surfaced, internally related to an affair with a female Boeing executive. At a time when Boeing was desperately trying to clean up its ethical act, the board made the difficult choice to request and accept his resignation, which it did in March 2005.

Even in good times, managing a company of the size and complexity of Boeing would be a major leadership challenge. But these were not good times for Boeing. Phil Condit had been forced out as CEO, after nearly forty years with the company, in late 2003. Condit himself had not been personally accused of any wrongdoing, but there were serious ethical violations associated with Boeing’s government business under his stewardship. The violations occurred at senior levels of the company, so the board held him accountable for not exercising good judgment regarding controls and ethical standards.

When McNerney arrived, Boeing’s senior ranks were demoralized, and employees throughout the organization were frustrated and embarrassed. The reputation of Boeing had been seriously tarnished by its top leaders twice in less than two years. Stonecipher had already been working on repairing the company’s reputation and was working to build an internal culture of enhanced integrity and accountability. His removal as CEO created a fresh round of self-doubt, confusion, and consternation among many Boeing employees. It was a clear bump in the road in the transformation of the culture.

Having seen the crisis unfold from his seat on the company’s board of directors, McNerney understood the legal, political, and business dynamics that surrounded the Boeing scandals and the company’s efforts up to that point to reach a resolution. And he had developed a sense of timing and a framework for the judgments he would ultimately need to make to put the past issues to rest and focus his team on the future. McNerney also was acutely aware that how he handled this crisis would be a watershed in his leadership, affording him the opportunity to reenergize the transformation of the Boeing culture around ethics and integrity.

Anyone who knew Jim McNerney would have known that he was not the type to leave the crucial judgments of something as important as the Global Settlement to others. McNerney is a world-class team player. Others, including his board and legal team, played key roles. McNerney relied on them for their insights and judgment. But the course of events was profoundly shaped by Jim McNerney. He had a plan for restoring Boeing to the top tier of worldwide industry, and that plan called for a quick and amicable settlement with the Department of Justice and a sincere and dedicated effort to restore Boeing’s reputation and relationships with both internal and external stakeholders.

TEACHABLE POINT OF VIEW AND JUDGMENT CALLS

In the second chapter, we laid out our framework for how successful leaders go about making good judgment calls. In the rest of this book, we will delve into the judgment matrix we described there. We will talk about how the good leaders we have observed go about marshaling their resources to make wise decisions and take effective action. We believe that this framework will help other leaders think about their own judgment-making processes. It will also help them build organizations that promote good judgment and develop the judgment-making abilities of others. But before we do that, we first need to take a couple of chapters to talk about some resources and attributes that good leaders bring to bear when working through the judgment matrix.

How a leader works the judgment process depends to a great extent on who the leader is. Winning leaders, the ones who continually make the best judgment calls, have clear mental frameworks to guide their thinking. They have stories running in their heads about how the world works and how they want things to turn out. And they have the all-important qualities of character and courage. They have the internal discipline and the guts to make the right calls and to follow through.

The personal resources that judgment leaders bring to the table are critical factors in their repeated success. The matrix is a valuable tool. It works. But to make good judgments, leaders must know to what aim they are using the matrix. They must know what they are trying to accomplish, where they are headed, and how they will get there. And they must have the courage to make tough calls and execute them. Any leader who follows the matrix can improve his or her judgment batting average, but without mental and moral rigor, they will never achieve consistency.

In our earlier work, we have both written extensively about transformational leadership, and about those who creatively destroy and remake their organizations for success in tomorrow’s world. We have devoted our careers to studying how leaders build companies that succeed in the marketplace and other organizations that accomplish their missions. We have been particularly interested in how leaders transform their organizations to maintain success in changing environments. We have talked about how winning leaders are teachers. They drive their organizations through teaching, and they develop others to be leader/teachers.

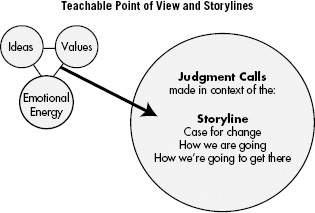

Noel has written that winning leaders are good at this because they have made the effort and spent the time to develop Teachable Points of View (TPOVs).5 TPOVs are what enable leaders to take the valuable knowledge and experiences that they have stored up inside their heads and teach them to others. Winning leader/teachers use their TPOVs to convey ideas and values to energize others and to help them make clear, decisive decisions.

While TPOVs are essential to transformational leadership and to developing others as leaders, TPOVs have an equally crucial role to play in guiding leaders’ own decisions and actions. Roger Enrico, the former head of Pepsico who is a world-class teacher, has remarked that “having a point of view is worth 50 IQ points.”6 If that is the case, which we think it is, then having a TPOV is worth at least another fifty points when it comes to making judgment calls.

The TPOV comes alive and is most valuable when a leader weaves it into a storyline for the future success of the organization. As a living story, it both helps the leader make the judgment calls that will make the story become a reality and enlists and energizes others to make it happen.

As Noel wrote in The Leadership Engine: How Winning Companies Build Leaders at Every Level, the story and the TPOV must be inextricably linked.

These points of view set the direction and provide the guiding principles for the organization. But these “points of view” can’t be just dry intellectual concepts. To be effective, leaders must bring them alive, so that followers can and will act on them. This means that they must make them understood not just rationally, but emotionally. And they do this by weaving them into personal stories. The stories and the points of view are intertwined. Without the stories, the points of view are often just arid concepts. However, the stories must be solidly based in the leader’s points of view. Otherwise, they are just idle entertainment that amuses and engages, but doesn’t lead anyone anywhere.7

A key factor in Jim McNerney’s judgment calls surrounding the settlement with the Justice Department was that he had a TPOV about how Boeing was going to succeed in the future. He had clear ideas about what would drive success for Boeing. He knew what kind of culture and values he needed to cultivate to make those ideas work. And he had a strong sense for how to reenergize workers to help bring this vision to reality. Furthermore, he had begun crafting those elements into a storyline for Boeing’s future success.

McNerney had a scenario that he was developing in his head about how the elements would interplay as the future unfolded. This meant that as issues came up and each judgment call needed to be made, McNerney could plug options into the mental scenario he had developed and foresee likely outcomes. The storyline, with its comprehensive scope, made it easier for him to keep an eye on the whole picture of what needed to happen at Boeing, rather than getting too narrowly focused on the specific issue at hand.

A leader’s TPOV guides the development of the narrative. But it is the leader’s capacity for writing his/her future story for the organization that provides the platform for making the key people, strategy, and crisis judgments. The larger and more complex the organization, the more the story looks like Tolstoy’s War and Peace written as a look forward, not backward.

All of us have the capacity to mobilize action through vision and stories. We do it when we plan a vacation. We create a vision of the future, a future story with real events, people, drama, and so on. We try to envision what our trip to Grand Cayman will be like, the vision of the hotel on the beach, the scuba-diving trip, the dinner at the restaurant on the beach. The story may be totally out of touch with reality when it turns out that we get booked in a crummy hotel with bad food and the scuba trip turns out to be a disaster. The story, however, got us motivated to make the trip. The more competent we are at crafting not only compelling stories but ones based in practicality, the more effective we are at making things happen in our own lives.

This is truer for a leader. Leaders play the complex role of playwright, producer, and director. They draft the dramas in their minds. They take them “off Broadway” and test them out with a few trusted friends and colleagues. They revise and rewrite in response to the criticism. Then they put them onstage for the wider organization, continuing to revise and adjust even through the execution phase. The basic storyline is the platform for subplots and stories throughout all levels of leadership.

Leaders’ storylines are always organic. They evolve in response to changing circumstances. Nonetheless, they are solid and concrete enough that they give good leaders solid foundations that enable them to deal with scale and complexity and uncertainty. Leaders who have storylines running in their heads are much better equipped to deal with unexpected events.

Clear storylines give leaders the critical ability to engage in “planful opportunism” when it comes to judgment calls. The “planful” part is the leader’s storyline for the future, built on a solid TPOV. The “opportunistic” parts are the unpredictable moments when the need or opportunity arises for a judgment call. Storylines help leaders make good calls regarding people and strategy, and they are absolutely essential for successfully handling crises.

JIM MCNERNEY’S STORYLINE FOR BOEING

Jim McNerney’s storyline for Boeing was a strong theme of high ethical standards that meant a new partnership with all of Boeing’s stakeholders, both internal and external. This theme was a key element in making that scenario play out as he wished. That understanding directly guided his judgment calls about how to move Boeing beyond the ethical and legal issues that had dogged its recent past.

Even before his arrival as CEO at Boeing, McNerney had been at work developing his TPOV and crafting its elements into a storyline that he could follow in his head and use to teach and lead others. As he gained knowledge and experience on the inside, including adapting and incorporating many positive aspects of the existing Boeing culture and business plan, he would refine and reshape elements of it. Here are the elements of McNerney’s TPOV for Boeing:

Ideas: About How to Make the Organization Successful in the Marketplace

McNerney inherited a focused set of core competencies, which Boeing leadership had defined several years prior, that were used to guide strategic decision making.

CORE COMPETENCIES

- Detailed customer knowledge and focus

- Large-scale systems integration

- Lean enterprise

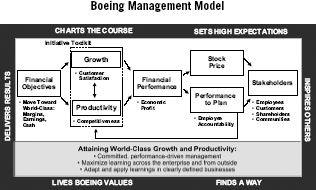

McNerney added a management model to align and integrate the company through common, disciplined approaches to leadership development, integrity, and values, and to work growth and productivity simultaneously to drive better business performance.

Values: About How We Behave and What Good Leadership Is at Boeing

McNerney inherited a strong set of values to which all employees aspired: leadership, integrity, quality, customer satisfaction, people working together, a diverse and involved team, good corporate citizenship, and enhancing shareholder value. He added a comprehensive model of leadership that not only defined the attributes Boeing would expect of good leaders but described how to animate leadership development throughout the ranks.

DEFINE IT: A BOEING LEADER

- Charts the course

- Sets high expectations

- Inspires others

- Finds a way

- Lives Boeing’s values

- Delivers results

MODEL IT: IN ALL WE DO

- Action/words

- Every day

- Leaders leading leaders

EXPECT IT/MEASURE IT/REWARD IT

- Reinforce in HR processes

TEACH IT: THE BOEING LEADERSHIP CENTER

- Candor/openness

- Leaders teaching leaders

- Step function impact

Energy: How to Generate the Positive Emotional Energy to Get Things Done

- Tie pay to performance on values as well as financials

- Help people to grow

- Free people to act

- Maintain high standards

In previous writings, Noel has included a fourth TPOV element: edge, which is the willingness to face reality and make tough decisions. In the context of leadership judgment calls, exercising edge is the central phase of the judgment-making process. Leaders exercise edge when they make clear yes-or-no decisions.

The TPOV is framed in the chart “Teachable Point of View and Storylines” as three interrelated components—ideas, values, and emotional energy—that interact in the mind of the leader to guide the exercising of edge and the making of judgment calls.

Using these elements of his TPOV for Boeing, McNerney began developing his storyline. That storyline, which significantly guided his judgment calls in handling the Justice Department settlement, follows, and fully reflects his management model and other TPOV elements. It is drawn from comments McNerney made to Wall Street analysts and to Boeing shareholders:

The Boeing Company aspires to deliver financial results that match the quality of our people and our technology—which is a meaningful improvement from where we are today. In short, we expect to meet a significantly higher standard of overall financial performance. We intend to get there by finding ways to make Boeing bigger and better than the sum of its parts.

The foundation for this framework will be driving and nurturing a culture of leadership and accountability. We have started by setting challenging but attainable financial objectives and more strongly linking them to our own pay and career development. An intense but equal pursuit of productivity and growth will be the building blocks of our improved financial performance. We must have both growth and productivity—simultaneously—since they fuel each other. We will always remember that growth, our future, begins and ends with our customers. I am pleased that Boeing’s teams have made significant strides in living at our customer’s place and at our customer’s pace.

And we won’t stop there. Further, we will strive to address growth as a disciplined process, not as a series of intermittent opportunities. Through this approach, we hope to anticipate our customers’ needs better and earlier than our competitors do, respond faster, and solidify our standing as the preferred supplier for our customers around the world.8

By tapping into the creativity of both our own people and those of our partners and suppliers…there is no end of opportunity for adding value and taking out cost in the wonderful products we build and the valuable services we provide.

Our growth will be customer-inspired and customer-driven. In one of our principal businesses, our customers include the world’s airlines and the traveling public; in the other, they include the armed services of the United States and allied governments. These are terrific customers to have. Without a doubt, if we do a great job of listening to them and finding the best way to satisfy their needs, Boeing will continue to grow…year after year.9

TPOV and Storylines

Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered at the Lincoln Memorial in 1963, is one of the most famous and compelling examples of a leader transforming a clear, logical Teachable Point of View into a vivid and inspirational storyline. The goal of achieving it drove both King’s decisions and the success of the civil rights movement. The elements of King’s TPOV were powerful.

Here’s the TPOV:

- Ideas: King was driven by the belief that America would one day fulfill its own Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal.”

- Values: His speech championed dignified nonviolent protest.

- Energy (teamwork and urgency): He also stressed the life-or-death urgency of immediate action.

- Edge: “There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights.”

But the narrative story he created brought it alive and made it even more powerful. It was the plot line that he played in his head to guide his own judgments and that he used to effectively mobilize millions of others in the civil rights struggle:

- Ideas: The dream that his children would “one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

- Values: An emphasis on the power of faith to end conflict and advance justice and brotherhood.

- Energy and Edge: “With this faith we will be able to work together, pray together; to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.”10

It’s all there. All of the points of his TPOV about how Boeing is going to succeed in the future are in that short narrative. With this storyline running in his head, it was clear to McNerney that Boeing would be in a far better position to settle with the Justice Department sooner rather than later, even if it cost the company more in the short term in the form of a larger settlement payment.

Where Are We Going?—How Will We Get There?

While including all the elements of their TPOVs, winning leaders’ storylines aren’t dry narratives that can only be summoned up with the help of PowerPoint reminders. Rather, they are active, engaging stories that start in the present and lead toward a rewarding future.

Winning leaders create these powerful visions and stories for where their organization is going and how it is going to get there. Then, they use them as “self-talk.” They tailor them to their situations and their audiences. They can tell the two-minute elevator version or give the eight-hour Fidel Castro oration. But no matter what the level of detail, these future stories provide the context for leaders to make judgments about people and strategy, and handle the crises that inevitably occur.

Winning leaders’ storylines specifically address three areas of questions:

- 1. Where are we now? What is the hand we have been dealt? The storylines precisely describe and diagnose the current situation. This is the starting point for the journey. It often includes the strongest elements for motivating the drive to change.

- 2. Where are we going? What are we trying to accomplish? What are the benchmarks of success? How will things look and feel when we get there? The inspirational storyline here adds to the motivation for change, but more important, it sets the beacon. It defines the goal, and thus helps both the leader and the people in the organization to make judgments about whether a decision or action will get them closer to it or farther away.

- 3. How are we going to get there? This is part road map and part defining of roles. The road map part charts a path toward the goal and suggests some steps along the way. The role-defining part describes the kinds of behaviors and the contributions that people will have to make to execute the plan.

The version of his story that McNerney shared with his senior team in early 2006 was a more detailed rendering of the story than the one he laid out for the analysts and shareholders.

1. WHERE ARE WE NOW?

He had his case for change. Where was Boeing now, and where did it need to be?

I want it to be more global than it is. We resist global pressures in some cases. They’re not always immediate, but over time we’re going to have to become a more global company. That’s where the talent is, in many respects; and where the training is, in many respects. That’s where the markets are. The fact is we’ve got a big competitor to BCA in Europe that has half the market. And we’ve got to know how to do business globally as well as they do, if not a whole lot better. They’re going to start doing some things globally. So more global.

2. WHERE ARE WE GOING?

How would the company have to operate in the future to make itself a strong global competitor?

Over the years, Boeing had grown through some major mergers and acquisitions, the largest of which was the 1997 merger with McDonnell Douglas. And when McNerney arrived, it was largely operating as separate commercial and defense companies under a loose corporate umbrella. Part of his vision was to unify the company around common values and processes, and also to share best practices and eliminate the duplication of efforts.

The theme in my mind is it’s still one company, multiple businesses…each with separate, well-defined roles, with the sum being greater than the parts, and the financial results to prove it. I come back to that theme. That’s my vision of this company. We’re not there yet, but you can see that at least we aspire to some of that as we try to get leverage.

3. HOW WERE THEY GOING TO GET THERE? WHAT WOULD IT TAKE?

Now, what else? Sure, in five to ten years I’d like to see a step-function change in financial results. Sure, I’d like to see the market shares we’re beginning to get in (Boeing Commercial Airplanes) and some key (Integrated Defense Systems) programs to stay and even improve. So I’d like to see business results better than historically. I think every management team in the world wants that, and I want that because I’m like you: I want to win. I don’t want to lose. I want the other guys to lose.

But even more importantly, what I want is better, more excited leaders. That’s what sustains companies. We’ve got great leaders. We’ve got great people…. We’ve got a pretty good group of people, not only in this room but also a year or two behind them, that are going to be better than us. I want to help create that. I want to help create a generation of leaders that are better than us and that are even more excited about this company and about this business than we are.

Ultimately, he said, he envisioned a company that would prosper because it was filled with people who were able and excited.

I want Boeing to be the best place to work. It is, in many respects, now. I want it to still be that way, even more so.

I want Boeing to be the most admired company not only in aerospace but in the country. That’s what I want. That’s an aspirational goal for me…but at the end of the day, I still have this fundamental belief that if we can create an environment where our people grow, our company will grow. It’s that simple. Because we know what to do, if we’re excited about it.

The chart “Storylines and Judgment” identifies what makes for good storylines and how they guide the judgment process.

MCNERNEY’S PLANFUL OPPORTUNISM IN A CRISIS

We interviewed Jim McNerney about his decision to settle quickly with the Justice Department and his other early judgment calls at Boeing. He talked to us in terms of where the company had been and where it needed to get. One hallmark of great leaders is their capacity for what we call “planful opportunism.” This is the ability to turn an unexpected crisis or event into a way to drive a very thoughtful and planful agenda. This is exactly what McNerney did: he took the scandal and resulting crisis and turned it into a driving force for the cultural change he wanted to foster at Boeing.

STORYLINES AND JUDGMENT

THE KEY ELEMENTS OF THE LEADER’S STORYLINE

- It interprets the present and shapes the future.

- It is both rational and emotional.

- Building a storyline for a company is an organic, ongoing process.

- The storyline creates a sense that the organization is embarked on an ongoing journey.

- The storyline is constantly updated as circumstances change.

- The storyline defines the beliefs, attitudes, and values that the company holds and that its employees share.

- The storyline creates a sense of purpose for the business.

- The story comes from the heart and engages people emotionally and personally.

JUDGMENT

- Good judgments further the future story.

- Bad judgments disrupt and hinder the story.

- Leaders at all levels need storylines that are tied to the larger story to guide their judgments.

Over the years, as Boeing worked to integrate its merged and acquired businesses, it struggled to create a common culture and the operating disciplines that go along with it. “We had patterns there that were not healthy,” McNerney told us. The culture apparently was not strong enough to prevent the improper acts of some key people who put the whole company at risk. People were allowed to hide in the company’s bureaucracy, and the culture lacked comprehensive functional checks and balances on individuals’ behaviors. Nor was it a place where individuals felt it was their responsibility to stand up and be heard when something just didn’t seem right to them.

So McNerney made a determined judgment to preserve the many positive elements of the Boeing culture but to challenge those he felt were dysfunctional. First, he stood strongly behind the efforts begun before his arrival to gain the commitment and alignment of all 155,000 employees. McNerney told us, “Every employee each year personally recommits to ethical and compliant behavior three ways: by going through a thorough training regimen, re-signing the Boeing Code of Conduct, and participating in one of our Ethics Recommitment stand-downs with his or her business or function.” In addition there is an Office of Internal Governance, created under Stonecipher to consolidate investigative audits, and oversight resources, that reports to McNerney and has regular and routine visibility with the board of directors. This office monitors potential conflicts of interest in hiring, overseeing specific ethical and compliance concerns and cases for our top leaders.

Second, he put his personal imprint on the company’s efforts to open up the culture. He is creating a work environment that encourages people to talk about the tough issues and to make the right judgments when they find themselves at the crossroads between meeting a tough business commitment and doing what is ethically right. McNerney says:

There simply can be no tradeoffs between Boeing’s values and Boeing’s performance. We want people to know that it’s OK to question what happens around them because that’s what surfaces problems early. Silence that ignores the misconduct of fellow workers is not acceptable…. Ethics and compliance are core to our leadership development, not off to the side. At the end of the day, the character of an organization—its culture—comes down to the behavior of its leaders and must be seen to be a central part of the whole system of training and developing leaders, and the whole process of evaluating, paying, and promoting people.

McNerney’s approach to the crisis—to get a reasonable settlement for both sides sooner rather than later and put Boeing on a new course—did work, and it created a new set of expectations for how McNerney and his team will conduct itself internally and externally for years to come. The judgments he made during this crisis clearly further the story he is creating for the future of Boeing.

Senator John McCain was Boeing’s toughest critic during the Druyun scandal. At the Senate hearing, McCain credited Jim McNerney’s judgment for a key decision that followed the settlement itself: a decision not to take a tax deduction for the huge cost of settling with the Justice Department. Senator McCain told the packed hearing room, “The fact is that Boeing did not have to make the decision it made on deductibility. But it did. And when coupled with the internal changes the company has made, what Boeing did here conveys to me how serious the company is to truly reforming and starting fresh.”

McCain’s comments were a testament to the leadership of Jim McNerney, who makes all of his judgments in the flow of his future story for Boeing. When he is faced with a key people decision, he places it in his mind in his storyline; he pictures how this person will interact with others to further the story. The strategy decisions, likewise, are done in the larger context of his story. And he faces crises not as one-off “put out a fire” situations, but in the larger context with a view to leveraging his longer-term storyline.

McNerney also seized an opportunity at the Senate hearing to further his leadership agenda by summing up his testimony with:

Mr. Chairman and members of the Committee, in my fourteen months as the company’s chairman, president, and CEO, I have made it my mission to understand the root causes of what went wrong in years past. And I can attest that those former employees referred to in the settlement do not represent the people at Boeing, who are devoted to conducting their work ethically and in the best interests of our customers and our country.

Boeing is fully committed to operating at the highest standards of ethics and compliance. I will continue to do everything in my power to ensure that the company never finds itself in a situation like this in the future.11

Throughout the remainder of the book we will meet other leaders who are making judgments on the platform of their future storylines.

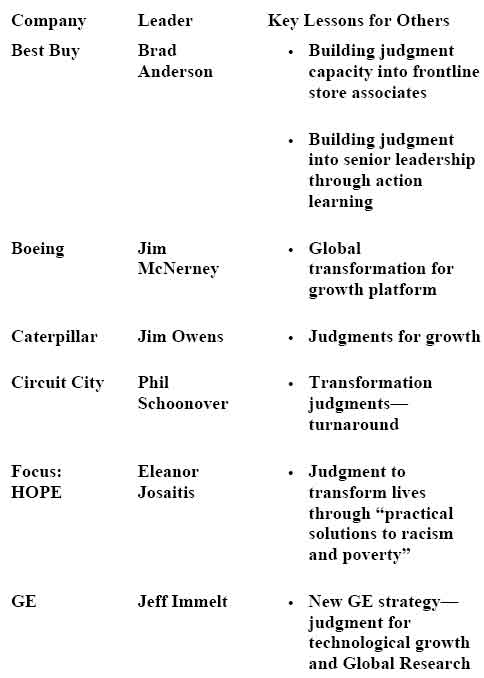

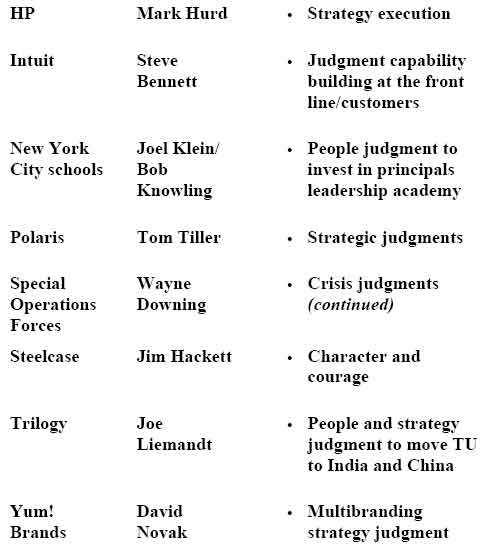

THE MAJOR WRITERS AND PRODUCERS IN THE JUDGMENT DRAMA

There are many leaders who were interviewed and studied for this book. They are the ones who are producing, writing, and directing their organizational stories into the future, figuring out when to make the big judgments about casting (people), plots (strategy), and crises. Here are the major ones.

Leaders make important judgments on the platform of their Teachable Points of View and the storylines they have for the future of their organizations. Much as Martin Luther King Jr. used his “I have a dream” narrative to guide his judgments about people, strategy, and crisis, CEOs like Jim McNerney use their own corporate storylines to lead them to sound judgments.

The storyline is never complete and always being modified by the judgments the leader makes. However, without a solid storyline, the leader’s judgments are disconnected acts that may or may not move the organization forward.