5

PEOPLE JUDGMENT CALLS

People Judgments Are the Platform for Good Strategic and Crisis Judgments

People Judgments Are the Platform for Good Strategic and Crisis Judgments

- Who-is-on-the-team-or-off-the-team judgments.

- Building a team at the top to support good judgment.

P&G CEO Lafley Making a Critical People Judgment to Head Up Baby Care

P&G CEO Lafley Making a Critical People Judgment to Head Up Baby Care

- Framing and naming the judgment.

- Making the call but failing to mobilize and align his team.

- Creating a redo loop to get alignment.

Team First, Strategy Second

Team First, Strategy Second

- McNerney’s Teachable Point of View.

On the morning of June 6, 2000, A. G. Lafley was in San Francisco. As the fifty-two-year-old president of Procter & Gamble’s global beauty care business walked into a nine A.M. meeting, his cell phone rang. The call was from P&G headquarters in Cincinnati. The caller was John Pepper, now retired P&G chairman. The message to Lafley was brief: come home. Immediately.

The last thing Lafley had done the previous day, just before leaving Cincinnati, was to meet with P&G’s chairman and CEO Durk Jager. The meeting between the two top executives had been routine. They met often. Lafley got along well with the brusque Dutch-born leader and was seen as a likely successor to him. But Jager was only fifty-seven years old and had held the top job for just seventeen months.

So when Pepper asked Lafley if he was prepared to accept the job as P&G’s president and CEO—immediately, Lafley was stunned. After a moment he said yes and Pepper told him to get on a plane. The two would talk later. As he flew back across the country, trying to behave normally with the other P&G executives on his flight, Lafley didn’t know if he had been offered the job or if the board was just considering him. And why exactly was the job open? What had happened to Durk Jager?

The board officially voted to name A. G. Lafley president and CEO of Procter & Gamble the next day, and the following morning, June 8, the change at the top was announced to the public. Durk Jager had resigned and was leaving the company.

As Lafley took the reins, the company was in turmoil. Jager’s aggressive plans to grow the company by launching new products and acquiring other successful businesses hadn’t worked. In an effort to make its management structure more global, he had drastically reorganized the company and in the process succeeded in confusing and demoralizing thousands of workers. As a result, in recent months Jager had had to reduce two P&G earning projections. And on June 5 it became apparent that another downward revision would be necessary.

P&G’s stock was in a tailspin. On March 7, the day the spring quarter’s earnings projection had been reduced, P&G shares had tumbled 30 percent. The total drop from a January peak to the day that Jager left five months later was 50 percent. The company was in crisis. The biggest crisis, Lafley would later tell us in 2005, “was not the loss of $85 billion in market capitalization. The far bigger crisis was the crisis in confidence…particularly leadership confidence.” As Lafley recalled: “P&G business leaders (had) retreated to their bunkers. Leaders were lying low. Heads were down…. Business units around the world were blaming headquarters for their problems. Headquarters was blaming line business units. Employees were calling for heads to roll.” Meanwhile, analysts and investors were irate. Retirees, whose retirement plans were built on P&G stock, were distraught. In short, as the new CEO saw it, “We’d made a mess, and we had to fix it.”

The question was, how? John Pepper lasted as CEO for only three and a half years in the mid-1990s because he had been unable to get the tired old consumer products company on the road to profitable growth. Jager’s new-product and globalization strategies were aimed at fixing a fundamental problem at the company. So just backtracking from Jager’s radical changes would not fix the ailing company. But doing nothing was also not an option.

The company had an “emergency room” full of problems, and Lafley had only a finite amount of time and personal energy. He had to decide where to apply his limited resources to gain the most leverage and produce the greatest benefit. So he started with people issues.

Judgment calls about people are the most critical ones that leaders have to make. This is because they have a huge impact on everything a company does. Strategy calls are important because they set the objectives and the agenda. And crises are important because they, by definition, threaten the well-being of the organization. If they weren’t high-stakes with a potential for disaster, they wouldn’t qualify as crises. But when it comes right down to it, it’s the people who make things turn out well or not. A good team member can fix a call that is going wrong, and a bad one can mess up even the most brilliant decision.

The P&G board’s decision to accept Jager’s resignation was thus the critical first step toward fixing the company’s problems. As the new leader, Lafley needed to pull the company out of its current crisis and devise a strategy that could turn the company around. But most important, he needed to build a strong team that could make the necessary judgments and take the effective actions to carry the company to success.

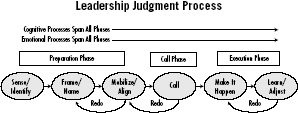

In many ways the process for making good people judgments is similar to that for making other types of good judgments. A leader has to recognize the need, frame the issue, and mobilize and align the parties who can provide the information and advice needed to make a good call. Then the leader must make the call at the appropriate moment, and follow through on the execution to make sure that the result turns out as well as possible.

People judgments are the most complex of the three domains for several reasons. First, a judgment about whether someone will be a good leader is a judgment call about how well they will do making other judgment calls. Will they be able to build a good team? Develop effective strategy? Deal with the inevitable crises? Fundamentally, a judgment about selecting a person should be based on how well he or she will operate in all cells of our judgment matrix.

The evaluations do not have to be made explicitly, and sometimes they are made intuitively, but to make a solid call about the likelihood of the person’s success, a leader needs to consider them all. The judgment matrix plays two roles in making good people judgments. First, the leader making the judgment needs to follow its process; second, the matrix provides the framework for measuring the candidate. It is a template for examining the candidate’s track record across the three domains—people, strategy, and crisis—as well as his or her depth of self-knowledge and capacity for knowledge creation at the social network, organizational level, and contextual level.

People calls also have other distinct challenges. Unlike strategies, the “objects” of people judgments are humans who make their own judgment calls and engage their own political circles even as the process unfolds. In a competitive world, no judgment call is ever made in a static situation. But in people calls, the dynamics are more complex, if not more fluid, than in other realms.

Leaders do, of course, get attached to ideas. They become enchanted with a visionary dream. They fight so hard to explore an intriguing possibility that they become too invested, emotionally and/or financially, to accept outcomes that fall short of their goals. But with people, the emotional stakes are much higher.

No matter how hard-nosed some leaders may appear, they all have emotions that affect their judgments. They have feelings about other people. They become attached to them, or maybe detest them, to degrees that hardly ever apply when they are considering strategic business plans. And it’s these feelings that can keep them from making good, objective calls.

Wayne Downing, the late four-star general who ran the Special Operations Forces, told us that “most of my bad judgment calls were generally about people. There have been times when I knew I had to take people out of a position. I knew they weren’t going to change, and they weren’t going to do what had to be done. But it’s traumatic when you do that. The higher up you go, the more traumatic it is for the organization to remove people, and you don’t like to do that, but in the final analysis you have to.”

Even Jack Welch, who is highly regarded for his track record in hiring and developing thousands of leaders during his tenure as CEO at GE, told us that at the end he was still batting only about 800. He estimated that as a first-time manager starting out, he only got about 50 percent of his people calls right, but even after twenty years, he thought he still got 20 percent wrong.

Of course, Welch set the bar for talent very high, so probably some of the hires that he considered failures would have been roaring successes in the eyes of others or in other organizations. But the point is that getting people judgment calls right is very difficult.

In our research for this book, we interviewed and polled hundreds of people about their good and bad judgment calls. An amazing number of them told us that many of their bad judgment calls occurred when they had overridden their gut instincts. You have to remember that these conversations were influenced by hindsight, when the results were in and the person was second-guessing him-or herself. But one interesting thing about people calls, we discovered, is that many leaders said the reason that they messed them up was often just the opposite. It was because they paid too much attention to emotions (“gut feelings”), and not enough to logic and intellect.

Joe Liemandt, CEO of Trilogy, an Austin, Texas–based enterprise software company he cofounded in 1989, frames the issue in terms of the compassionate Nobel Prize–winning missionary Mother Teresa and Mr. Spock, the stony half-human/half-space alien of Star Trek fame.

“You know, I don’t know what the percentage is, but a huge percent of bad decisions around people I feel are made because they misalign the emotional and the logical. I know personally for me that that’s what I struggle with. I come to a good logical answer (to a situation) but then I can’t make myself make it because I don’t want the emotional pain.”

So, Liemandt explained, at Trilogy

we have a framework we actually use internally around tough people decisions. These are the ones like whether you lay off your friend or whatever. We call it “Spock and Mother Teresa.” What I mean is that when you’re faced with a tough people decision, most people feel uncomfortable, so they sort of Mother Teresa it. They don’t really give the good feedback to the person or they don’t make the decision to move them out. They stall, they delay, you know, they’re vague in their feedback, whatever it is. And then, because of a crisis or whatever happens, that they finally are forced to make a decision, they then become Spock and they basically become an asshole to the person. Then, they very abruptly deal with it.

What we try to do around it is the exact opposite, which is, when you’re faced with a tough decision you’ve got to be Spock upfront. Be super-logical, super-analytical, really ask yourself: “What is the right answer?” and don’t worry about the downstream implications right now. Just come to the logical right answer.

But, then once you make the decision, absolutely Mother Teresa how you deal with the person. Be super-good, make sure you don’t delay six months before you tell someone you think they’re bad and then cut them off and give them a lousy severance. It’s tell them six months earlier that you’re going to be moving them out of the organization and give them six months extra severance or help them find a new job. That framework all of a sudden makes making the right decision six times easier.

SELECTING THE TOP TEAM

In the six years that A. G. Lafley has been CEO, P&G has turned around. Its earnings and stock price have climbed more than 58 percent. It has consolidated its position in its core businesses, including diapers. And it has made several substantial acquisitions, including Clairol and Wella, in the hair care markets. Its 2005 $80 billion purchase of Gillette has given it a solid entry in men’s care.

A. G. Lafley’s success in the months and now years since his appointment in June 2000 is a reflection of his good judgment calls. Ironically, many of the steps he has taken, including the acquisition of Gillette, Jager had attempted. The difference was that Lafley was able to get them executed while Jager did not. One of the primary reasons is that Lafley did a better job selecting and leading people.

“I came in during the middle of the night in June of 2000 in sort of emergency circumstances,” Lafley told us. “I actually was thinking on that long flight back from San Francisco, when I had four hours to think alone, that we had a pretty good team. Some were team members or individuals who were de-motivated for various reasons. But I honestly thought that the team had talent and a lot of experience and would come together. But in the first hundred days, all of a sudden guys that looked pretty good as colleagues didn’t look like they were going to have the right mind-set to take on the tough calls and choices we would need to make, and to take their game to the next level on a collaborative team. And it was clear that we had other up-and-comers with more appetite for change and more courage to make tough calls.” So, over the next two years, more than half of P&G’s top thirty executives left the company or moved on to other assignments. “It wasn’t that they were failing. It was that they were not going to take us to the next level. So we worked through that, and then we worked through the priorities, which ones we have to change first, second, third.”

LAFLEY’S P&G STORYLINE

Lafley’s storyline for the future success of P&G gave him the stage to make critical judgment calls. Here is how he told it to CEO Magazine in late 2005:

Everything begins here with our purpose. It’s very simple. We provide branded products that improve everyday lives. The values of the company are integrity, trust, ownership, leadership, passion for service and winning. Then we have principles such as “respect for the individual” and “innovation is our lifeblood.” Every employee has one of these little pamphlets. It’s on every Web site and in almost every conference room everywhere in the world. We’re quite public about all that and we’re even, in a shorthand kind of way, pretty public about our strategy. We’re not surprising our competition. They know broadly what we’re trying to do.

Then we turn to strategy, which is choices. Our whole focus has been to grow and profit from the core—and that means core businesses, core capabilities, core technologies. Our second choice was to expand our portfolio in health, personal care and beauty care because that would serve more consumers’ needs for longer lifetimes. Then the third one is to serve low-income consumers who can’t always afford our products, especially in developing markets. I say this because I live it. But I guarantee you that if you dropped into any group, anywhere, in the company, they could explain all this.

Then (the other piece of this is) selecting, developing, training, teaching and coaching the leadership team. They are the leadership engine. We’ll do at least $68 billion in sales post-Gillette. We’re in 80 countries. We sell in 160. We have over 100,000 employees. It’s going to go to 130,000 or 140,000. This company is run by 20 presidents of line businesses and 100 general managers and their functional leadership that supports them. So that’s about 250 people. It’s one team with one purpose and one dream and one set of strategic choices.1

Although Lafley refined his storyline as time went by and he gained experience, the essentials were in his mind from the beginning. So when he became CEO, he went business by business evaluating and judging what he needed to.

One of the biggest calls that Lafley made early on was to pick Deb Henretta to be in charge of the baby care business. With the storyline in his mind that the overall success of P&G would depend on the quality of its leadership team, he made a judgment for the baby care business that surprised a lot of people. He selected someone with no expertise in the area because he thought that she was a good leader and would be able to bring a needed new perspective to the business.

The steps he took as he worked his way through this judgment call are instructive. He didn’t get everything right the first time. He had to circle back and cover some bases that he missed. The result was a success because he was constantly aware of the importance of getting each phase right and because he stuck to it until he got it right.

ANATOMY OF A PEOPLE CALL

The unique aspect of people judgments is that the full judgment matrix is the framework for making a key people judgment. Whether someone is a good leader or not is based on their track record of past judgments about people, strategy, and crisis; it is also a prediction about how well they will do on judgments in new and future settings. This is unlike strategy or crisis judgments, which only deal in their unique domain.

JUDGMENT PREPARATION PHASE

Step 1: Sense and Identify

The first thing Lafley had to do before making the judgment call was to sense and identify the problem that needed solving. The sensing part was easy. “Baby care is our biggest single category after laundry. It was struggling,” Lafley told us.

Kimberly-Clark’s Huggies took leadership of U.S. baby diapers in the mid-’80s because we made a huge strategic mistake. We had a Pampers brand with about 65 percent market share. Then we introduced a new technology—shaped diapers—but instead of making the new shaped diapers on the flagship Pampers brand for better fit and performance, we introduced them on a new brand. Luvs was a huge success.”

Overnight, it went to like a thirty-plus market share. But we, of course, were cannibalizing unmercifully. So we took most of it out of Pampers. We reduced Pampers from a 65 percent to

70 percent to a one-fourth share. We have Luvs at a 30 percent share. And Huggies came right up the middle with an improved shaped diaper. Pampers ended up being third into the market with the new shared diaper technology. When the dust settled, they had the biggest brand. We had the biggest company (total), but we divided our forces. We weakened our position. In addition, they introduced the pull-up or pull-on diaper. We all had the technology at about the same time. We all had the patents, but they went to market, and we didn’t. So we were in tough shape in baby care.

P&G’s dominance in the baby care market was flagging. It had two successful brands of diapers, Pampers and Luvs, but neither was as strong as Kimberly-Clark’s Huggies. The reality that there was a problem in baby care was obvious.

Identifying the exact problem was not, however, as straightforward. Lafley needed to “fix baby care,” but there were many ways to go about doing that. He could have identified the problem as an issue of management performance. The unit currently wasn’t running very well, but maybe the problem was that people weren’t working hard enough or smart enough. If they were coached, or removed and replaced with better performers out of the same mold, maybe things would turn around.

Alternatively, Lafley could have focused on marketing. Since diaper sales weren’t as strong as they once had been, maybe the problem was the marketers. Or he could have decided that the problem he needed to fix was distribution or research. But he didn’t choose any of those.

Instead he identified the problem as having a business model and approach to the business that was off the mark. “I felt that we were technically competent in baby care,” he says, “but that the machine guys and the plant guys and the engineers were running the show. And our problem was on the consumer and the brand equity side.”

Step 2: Frame and Name

Once he had identified the need for a total transformation of the baby care unit, Lafley framed the issue as leadership. The problem wasn’t that the unit wasn’t well managed, and it wasn’t that the people in the unit were poor players. The unit needed a new strategy, and the only way to get that new strategy was to get a new leader and a new top team in place. He framed his task specifically as finding a transformational leader. He needed someone from outside the division who would be able to look at the business with fresh eyes.

Baby care was technology and machinery-centric rather than customer-centric. The goal that he wanted to achieve was to transform the culture and the way the people in the baby care unit thought and conceptualized their jobs. “I wanted someone who had not spent a minute in baby care to go in. I wanted a good leader, and an outstanding consumerist and brand builder.” The framing of the people judgment that Lafley had to make for baby care was to look for a leader who would, in turn, make good judgment calls. He needed someone who could build a good team, align people throughout the organization, develop a smart new strategy, and pull the unit out of its current crisis.

Lafley created the frame and specifications for the new leader as someone who would make good judgment calls, and then he started thinking about specific candidates who could successfully fill the role. The judgment matrix is how Lafley both intuitively and explicitly framed the leadership judgment. He wanted a leader who could make good people judgments so as to quickly assess who should be on or off the baby care top team; then he wanted a leader who could make the strategic judgments to turn the business around; finally, the leader had to be good a making crisis judgments as the business was in a crisis.

Step 3: Mobilize and Align

Once he had framed the call as finding a leader who could make a series of good judgment calls, Lafley began mobilizing others to help create a slate of candidates. He worked with Dick Antoine, head of HR; and with Mark Ketchum, group president with responsibility for baby care, family care, and feminine care, both of whom agreed with his framing. They quickly came up with a slate of candidates, at the top of which was Deb Henretta.

Then they began to assess her, based on her ability to perform in the various boxes of the judgment matrix. The process involved both explicit reviews of Henretta’s past performance and her HR assessments, and more general discussions with a network of people who knew her and had worked with her.

Here are the kinds of questions that leaders need to consider to answer in each cell of the matrix.

Questions for Each of the Cells of the Matrix

- 1. People/Self: Does she have a solid sense of herself? Does she have a Teachable Point of View; ideas, values, and emotional energy to guide making good people judgments? Is she comfortable making tough decisions that affect the lives of others?

- 2. People/Social Network: Does she know how to draw on the resources of those around her to get the input she needs? Is she able to figure out who she needs to involve? Can she align and energize them to support the ultimate call on key people?

- 3. People/Organizational: Does she know how to design and implement organizational processes that support her in making good people judgments?

- 4. People/Contextual: Is she willing to tap relevant stakeholders for input? Does she know when to ask, and how to get meaningful input?

- 5. Strategy/Self: Does she see herself as a change agent? Does she look over the horizon? Can she conceptualize new opportunities and execute new strategies?

- 6. Strategy/Social Network: Will she get the people with the right expertise and right chemistry in the room? Will she have the discipline to exclude those with little to contribute? Can she frame the issues so that the best solution is reached?

- 7. Strategy/Organizational: Can she build the processes to get all levels of the organization aligned to execute the new strategy? Can she energize them to deliver on it?

- 8. Strategy/Contextual: Can she teach the rationale of the strategy to key stakeholders and get them aligned with her? Can she create recognizable benchmarks and deliver on them?

- 9. Crisis/Self: Will she assume personal responsibility for dealing with crises? Does she have a strong Teachable Point of View to guide her? Is she clear on her ultimate goal? Does she have strong values to shape what is acceptable and what is not? Does she have the self-assurance to make clear, firm decisions when necessary?

- 10. Crisis/Social Network: Does she have a high-trust team? Can she mobilize them quickly? Can she efficiently elicit a range of options and honest discussions of them? Can she manage conflict so that it is productive?

- 11. Crisis/Organizational: Can she focus the organization on essential actions? Can she impose the needed discipline without sapping morale?

- 12. Crisis/Contextual: Can she manage while in the spotlight?

Can she manage external expectations? Can she build/maintain the trust of others that will buy her time to develop and implement effective solutions?

After going through all the cells of the matrix, Lafley concluded: “She was a laundry person, but I knew what she really was, which was a tough and decisive leader. She was great at understanding consumers and great at branding and great at building innovative programs. And that’s what we needed.”

At this stage, Lafley made a big misstep. Having been at P&G for over twenty years, rotating through jobs with increasing scope, Lafley knew who was in the candidate pool. He didn’t do a big search, because with his own knowledge and the supporting information provided by his HR chief, Dick Antoine, and Mark Ketchum, he didn’t need to. He knew Deb Henretta, and he had the information about her he needed to answer the questions about how she would perform on the matrix questions. He was confident that she could do the job.

Still, his failure to mobilize a search team cost him, and cost him dearly. He didn’t need a lot of input from others in order to make a good choice. But by not consulting his top team members, he missed an opportunity to get them aligned behind her. While he didn’t feel that he needed their advice, Henretta would need their support, or at least their acquiescence, to succeed in the job. Lafley jeopardized the outcome of his judgment call because he didn’t pay sufficient attention to the politics involved or to the feelings of the other senior executives who had their own candidates.

As a result, on the day he announced that Henretta would be the new head of baby care, “there was almost a revolt,” he says. “I announced Deb’s appointment at the morning management meeting. It was before the announcement went out to the company. It was to go out in a day or two. By three o’clock the revolt was well under way. All of the vice chairs and group presidents were ticked off because they had their own candidates ready for promotion.”

JUDGMENT CALL PHASE

The “call” phase of judgment-making is often as quick as the flipping of a switch. As Jeff Immelt describes his style, he does a lot of consulting with others, and then, “boom!” he makes the call. In truth, most judgment calls actually are made in the blink of an eye. At one moment a leader hasn’t chosen a course of action and by the next, he or she is ready to move on to the execution phase.

Even though many calls do go this smoothly, leaders who have good judgment track records never assume that anything will happen so easily. Aware that the ultimate goal is to produce a successful outcome, they are always vigilant. They are constantly checking to make sure that conditions are as favorable as they can possibly make them to support the success of the judgment. If they need to take time and expand the decision-making process, they do.

In this case, that is exactly what Lafley did. When the revolt broke out, he stopped action and called the top team together. With everyone sitting around he invited each one to make their case against Henretta and/or for someone else. “I said, ‘Okay, here’s what we’re going to do. I want you to take your list. I want you to make the best case you can for why your candidate or candidates are a better choice than Deb.’ So we went around the table and I listened…sequentially, publicly in front of everybody else. Then I said, ‘Okay, you know there were a couple of good cases. But let me tell you why I chose Deb.’”

Lafley didn’t expect that he would change his mind as a result of the meeting, and he didn’t change it. Nonetheless, he did open himself up to the possibility. He heard his colleagues out and responded to their concerns directly and respectfully.

Lafley knew that even if the powerful vice chairmen and business heads were not transformed into supporters of Henretta, they were no longer justified in any visible resistance to the call. The important thing here is that he did not try to slam-dunk his decision. He made time before moving on to set the stage for success.

EXECUTION PHASE

Step 1: Make It Happen

At the end of the day Lafley knew the powerful vice chairmen and business heads were not all transformed into supporters of Henretta. Her selection was a gutsy one. At the time, the baby care organization was very male. Its values were around technical degrees and the ability to build innovative machinery, and Henretta was not at all technically oriented. She was interested in consumers and marketing.

“They thought she was from outer space because she was talking about the consumer. She was talking about how to create an innovation program to attract customers. She said, ‘I don’t even understand how that machine works. You need to understand what the consumer wants, then make the machine work for them.’ We were running an operation that had a machine as boss. We needed an operation where the consumer was boss.” (Think back to chapter 1 when IBM’s Lou Gerstner proclaimed that the company needed a customer in the CEO’s chair. Lafley came to that same conclusion for his baby care unit.)

Lafley clearly understood that making the call was part of a longer process that required his active role in the execution phase. He knew that if he was not careful to maintain his support of Henretta during execution, there were plenty of political land mines that could make his call go bad. Lafley clearly understood that his role was to stay with Deb not only in the “make it happen” first step but to be an active partner in the “self-correction” process.

So, after backtracking with the top team to defuse their rebellion, Lafley stayed on the job. This included giving her the political backing to replace key members of her team, to make sure that everyone knew that he was in full support of her success. He also made himself available for mentoring and coaching Henretta.

“I had a pact with her that if she needed to change somebody out to let me know, and we would do it,” he said. “I supported her every step of the way. In fact I pushed her to make all her decisions. I learned this in Asia: make as many of your people decisions as you can in the first one hundred days, because you have to get your team on the ground.”

Step 2: Learn and Adjust

This is where many CEOs and other leaders end up with bad judgments: they do not stay the course on execution and their failure to do so costs them the ball game. Lafley clearly understood that he was the head leader/teacher at P&G and that he had to own the judgment through all three phases. This meant being available to Deb as a sounding board, as a coach, and as a political backer when the going got rough.

Henretta was handed a massive transformation challenge, which included dealing with resistance to change, putting together a new team, and coming up with a new strategy while dealing with the very real crisis of a business in a downward business spiral. This all had to be done in a much bigger arena than she had played before. Thus the scale, the complexity, and the political dynamics were at levels far beyond anything she had ever dealt with. Stretching a leader to achieve Olympic standards required Lafley to be an Olympic-level leadership coach to Henretta. This included giving her the political backing to fire and replace key members of her team, to make sure that everyone knew that he was in full support of her success.

The judgment matrix provides the template for what the leader needs to accomplish and therefore it is also the template for what coaching and help might be required by Lafley. He, in turn, helped Henretta base her people judgments on the matrix, and build a team that was going to be able to make good people, strategy, and crisis judgments and develop others.

Lafley declared his judgment call on Deb Henretta a victory only after the business turned around and there was irrefutable evidence of her success as a leader. As we reflect on this example, we can see how Lafley used his storyline for building a leadership team that would take P&G to success and his TPOV, ideas, and values to make the judgment on Henretta.

As a result of her success in turning the business around, Lafley subsequently promoted Henretta to head of P&G’s Southeast Asia business, a position that has considerably more career runway (i.e., potential) for her and will stretch her in new ways around people, strategy, and crisis. She handled it well and was then promoted to group president for all of Asia.

Later, in looking back on the early days of his tenure, Lafley would explain:

We did four things:

- 1. We faced up to the reality of our situation.

- 2. We accepted change, and stopped trying to ignore or resist it.

- 3. We starting making choices, clear choices, tough choices.

- 4. We put together a strong, cohesive team to lead the business.

As we noted in laying out our framework about how leaders make good judgment calls, these four elements are all critical. We might not put them in that order. We would probably move the “strong cohesive team” up to the number one, but all of them are important.

TEAM FIRST/STRATEGY SECOND

We have taken the position that people judgment comes first. If there is not a team of trusted leaders, it is impossible to make good strategy judgments as the people politics will undermine what is good for the enterprise. This is what happened at Ford with Jac Nasser, in a company with a long history of politics and leadership changes.

Nasser was leading a massive strategic transformation of Ford and was handling a crisis, the Firestone tire troubles, when a small group of his top leaders pulled off a coup d’état. It is not possible to lead an organization through such turbulence without trust. In Nasser’s case he was too trusting, or did not have the authority to make the people changes that were necessary. When the crisis hit, Nasser spent his time and attention focused on curing the company’s ills while three members of his team used it as an opportunity to lobby Bill Ford to oust him so they ended up with all the power.

Carly Fiorina, former HP CEO, was fired not because of strategic judgment, but because she did not have the leadership teamwork with the board and with her own internal team. Her perfect storm hit, starting with missed earnings in August 2004 followed immediately with the firing of three senior leaders: Mike Winkler, head of customer solutions; Jim Milton, CSG senior vice president; and Kasper Rorsted, CSG senior vice president. This internal political turmoil, coupled with poor financial performance, dropped the stock price another 15 percent and gave the anti-Fiorina HP board members a window to go after her, which they did, getting her fired in early 2005. The lack of teamwork with the board exacerbated by the internal political turmoil without financial performance was the perfect storm.

Ray Gilmartin at Merck could not get the strategy right because he could not get a team of trusted leaders at the top. He simply grew too removed. Once there is a team that is reasonably cohesive, then the strategy judgment process can unfold with a reasonable chance of success.

When Jim McNerney spoke to us about his experience, he concluded that it is always people first, then strategy:

It’s all about understanding what organizations can and can’t do. That’s where the judgment comes in. It’s not about strategy. Strategy’s relatively easy to define. You can do a market assessment, you can do a competitive assessment, you can figure out a way you can differentiate yourself, and if you can do it, then you can make money and grow. That is…It’s not easy, but I’m saying that is more commonly done well than the assessment that a leader has to make about execution—whether it can be done.

So if an organization’s standing in front of you with this great strategy and says that to implement it we’re going to do this using skills we’ve never managed before, selling to customers we’ve never seen before, yet it fits the strategy beautifully, judgment has to be applied. As to whether it can be done, how long it will take…And that is really derived from experience. I have a very different view of that than I did twenty-five years ago when I was a McKinsey consultant.