8

STRATEGY JUDGMENTS AT GE

Immelt: “My Job Is to Lead GE in…a New World.”

Immelt: “My Job Is to Lead GE in…a New World.”

- He foresees a global environment of slower growth, more regulation.

- He envisions a route to success through emerging markets.

Greatest Opportunities Are in Two Broad Areas

Greatest Opportunities Are in Two Broad Areas

- Developing economies will make big infrastructure investments.

- The biggest needs in developed areas will be medical and environmental.

GE’s Competitive Strength Will Be Its Technological Expertise

GE’s Competitive Strength Will Be Its Technological Expertise

- It will develop new technologies to serve new markets.

- It will find new uses for existing technologies.

IMMELT’S GROWTH JUDGMENTS FOR GE

The number one question is the organic growth rate, how much cash you generate to drive growth. Our goal is two to three times the global GDP. A company of GE’s size requires developing a $12 billion company every year. GE has to create a company the size of Nike every year to be able to have that kind of growth, and that’s the challenge.1

From its earliest days, General Electric has had a tradition of using groundbreaking research and professional management as a means for enhancing performance. The brilliant inventor Thomas Edison started the company with his patenting of the incandescent lightbulb in 1878. GE’s first CEO, Charles Coffin, set the fundamental building blocks of an integrated yet diverse company in 1893.

The company was integrated by common management discipline and practices, centralized financial and human resource controls, and the creation of the nation’s first industrial R&D center. It was a diversified electrical company making lightbulbs, streetcars, turbines, and related products that fed off a common R&D base. Coffin also created a set of standard management practices. By the 1920s, GE was conducting management retreats every summer in the “Thousand Islands” in upstate New York, with the leadership duo of Gerard Swope and Owen Young, president and CEO. This was the precursor to the current-day leadership development center at GE’s Crotonville. The Crotonville center, now officially named the John F. Welch Leadership Center, was created in 1956.

The GE DNA has always sought to add value across a diverse portfolio through technology transfer, financial and managerial disciplines, development of managerial and leadership talent, and common processes and systems. As Jeff Immelt has made judgment calls about how to reshape GE, the building blocks of this DNA of integrated diversity has informed his thinking and actions. Immelt articulated this DNA in the company’s annual report for 2005:

There are many companies that have been created through acquisitions that are frequently compared to GE, called conglomerates. However, our business model is designed to achieve superior performance through the synergies of a large, multibusiness company structure. The following strategic imperatives provide the foundation for creating shareowner value:

- 1. Sustain a strong portfolio of leadership businesses that fit together to grow consistently through the cycles

- 2. Drive common initiatives across the company that accelerate growth, satisfy customers and expand margins, and

- 3. Develop people to grow a common culture that is adaptive, ethical, and drives execution.2

This model is very different from that of a holding company or a portfolio of investments such as Warren Buffett’s. Buffett does not engage in any form of “integrated diversity.” So his strategy judgments are about which assets to buy or sell rather than about how to operate them. This holding company model is very different from the GE multibusiness operating company model.

At GE, strategy judgments are made in a much more hands-on context than in a holding company. But there are many paradoxes in the GE model. The heads of GE’s businesses have a great deal of local autonomy; yet there is also a lot of central control. For example, businesses at GE are of themselves Fortune 100 in size. (Infrastructure with sales of $46 billion ranks ahead of United Technologies, which is number 42 on the Fortune 100 list, and GE Industrial is bigger than all of Honeywell.) Jeff Immelt works closely with the CEOs of the businesses on their strategy, their budgets, their succession planning, and involvement in corporate initiatives such as lean Six Sigma quality program, growth platforms, leadership development, and technology transfer.

Immelt’s calendar reflects these tasks. He is personally teaching at Crotonville every few weeks. He visits the Global Research Center as many as four or five times a year. He gathers the heads of the business together with key corporate staff four times a year for multiday sharing workshops at Crotonville. Immelt also goes out to each business unit to do succession planning reviews, twenty days’ worth of reviews. He also holds all-day strategy reviews with each business, and operating plan reviews. Not one of those activities exists in a pure holding company. Judgment at GE is much more of a team sport, even though paradoxically the CEO makes the final call on the big items. During the preparation phase there is a great deal of mobilizing and aligning of key stakeholders for any given strategy judgment. This occurs in the various GE face-to-face forums for the heads of the business.

GE is also not like a new entrepreneurial company that starts with a clean sheet of paper. It has a legacy of 130 businesses, organizations, processes, and practices involving over 320,000 global employees. Thus, Jeff Immelt’s strategic judgments are, to some extent, limited and constrained by the past. But the success the company has enjoyed in the past also opens opportunities to him. GE’s size and wealth allow him to take risks and make bets that would be impossible for weaker companies.

Storyline

As he indicated in our early interviews, Immelt began crafting his storyline for where he would take GE by thinking about the in-house GE community. He wanted to make GE a better and more energizing place to work. But he quickly expanded his horizons to look at the global community.

To be effective a leader’s narrative storyline has to answer three questions: Where are we now? Where are we going? How will we get there?

In the early months of his tenure, Immelt began answering the “Where are we now?” question by describing the environment that he believed GE would encounter in the coming years. “I have taken over for a pretty famous guy, Jack, but to be honest with you, I have never thought of my job as replacing Jack,” he told a group of students. “It is a 120-year-old company. He happened to run it for a while, but it is a company that has staying power. My job is to lead GE in a new set of circumstances and a new world. Post 9/11, it is a different world. Even Jack would have had to change his style if he had stayed in the company in this environment. The job of the leader is to do the job of leadership in the time you are in.”3

In his first annual report letter in early 2002, Immelt described the world where GE had to operate. It was, he said, a world marked by slower growth and more volatility: “Jack left us a financially strong GE, as well as a culture that loves change. This is important because the world we knew in the late 1990s—a world of global growth, political stability and corporate trust—has changed. The U.S. economy began to slow in late 2000 and entered a recession in 2001. The world followed, with Europe and Japan in decline.”4

By September 2004 he had expanded on the storyline and made it more concrete. Here’s how he described the challenges that GE needed to overcome:

I look at it pretty optimistically. But it’s just going to mean that there’s not going to be a rising tide to lift all ships universally. There are going to be businesses that win and businesses that lose. There are going to be countries that win. There are going to be countries that lose. And so the need to be competitive has never been greater…which you’re going to see in the next five, ten, fifteen years.”5

In addition to the economic challenges of slow growth and volatility, Immelt saw important social changes that would affect how GE needed to do business. To attract and motivate good people, Immelt believed that GE needed to become more humane. But he also believed that better corporate behavior would be demanded by society and government.

It’s going to be “a world with more regulation, more laws, more cynicism about companies. And so that dictates that just being great isn’t enough anymore. The companies and people have to be both great and good to be successful in the future.”6

This reading of the state of the world informed the other elements of Immelt’s storyline about the direction he needed to lead GE and the kinds of behaviors he needed to encourage and develop to get there.

Based on this storyline and the underlying foundational points of his Teachable Point of View, Immelt would make judgments about what businesses GE should be in and how it would conduct those businesses.

Those judgments included his own pay. From the start, Immelt made sure that his pay package was moderate compared to other CEOs and that all his incentives are tied to GE performance. It is an example of contextual knowledge, reading the signals in the environment and responding to them appropriately, making the right judgment calls.

Given the assessment of the state of the world, Immelt’s next job was to figure out how GE could operate most successfully in that world. What products or services would be most in demand? And how could GE be the best at winning customers and delivering those goods and services? This is the “Where are we going?” part of the storyline.

The answer that Immelt arrived at was that the best way for GE to generate organic growth was to use its strong research and technology base to develop new markets. Some of the markets offering huge opportunities would be developing countries that needed to build infrastructure for power, water, energy, and transportation. In the more advanced economies, the best opportunities would be in as yet unserved, or underserved, markets. And these were most likely to be found in health care, in energy saving and production, and in environmentally friendly products. This assessment of where GE needed to go to succeed in the coming decades informed Immelt’s strategic judgments. These included buying Amersham, a leading company in the diagnostic imaging agents and life sciences markets, and increasing investment in wind-generation and advanced technology for the oil and gas industry.

The third element of Immelt’s storyline describes how GE will go about succeeding in these markets. His answer is, in part, about using the company’s strong technology and management systems for sharing knowledge to develop winning products. It is also about corporate citizenship. It is about not only what the company will deliver to customers but also about how it will behave in the global community.

Corporations, in Immelt’s view, would have to be more socially and environmentally aware. To be successful over time, they would need to make a greater contribution to the societies in which they operate. This would be mean greater efforts to support environmentally sustainable development and to attend to human capital issues such as housing, education, health care, and jobs.

Because he saw that global warming and the need for sustainable energy were serious concerns, he made the judgment to embrace the change and to come up with a GE response to them. In 2005 GE launched its Ecomagination initiative, which it described as “both a business strategy to drive growth at GE and a promise to contribute positively to the environment in the process.”7 It is a multidisciplinary campaign to apply GE technology to drive energy efficiency and improve environmental performance. He has always been clear that “green is green” for GE; he says that we are going to solve tough problems, yes, but Ecomagination has been a commerical enterprise from the start.

Immelt’s storyline for the future of GE includes new elements of global citizenship. Continuing Welch’s legacy of integrity, Immelt keeps reinforcing a commitment that GE must perform with the highest levels of integrity and compliance everywhere in the world. It must contribute and invest in the long-term well-being of the communities in which GE operates. It must build local capability, draw upon local resources to create jobs, and work with governments to implement solutions.

Finally, Immelt has provided much greater transparency to the investor community than in the past. He proactively set standards for other companies in the post–Enron, Tyco, Sarbanes-Oxley world. He is continuously pushing the boundaries of how transparent GE can become without giving away too much information to its competitors.

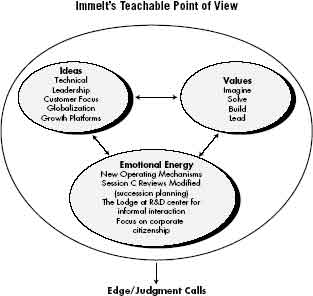

A leader’s Teachable Point of View and his or her storyline are always interwoven. It is easy to think of leaders’ storylines as a “fleshing out” or an animation of their Teachable Points of View, but in reality the action goes both ways. Sometimes leaders have TPOVs that they develop into storylines, and sometimes they have stories from which they draw foundational TPOVs. Most often a leader develops the story and the TPOV together. Sometimes the bullet points of the TPOV generate the narrative, but equally often a leader’s listening to the story produces the TPOV. Jeff Immelt’s TPOV for GE reflects his storyline.

Immelt Judgment Calls on Strategy

Based on his TPOV and storyline, Immelt has made a host of strategic judgments: some to get rid of businesses and others to add to existing businesses through acquisition. This is coupled with a massive emphasis on technology and R&D to build new businesses for the future. Immelt frames his judgments in terms of:

There are five traits that I think are consistent across GE businesses that I look for. I like businesses that are technically based, global. I don’t like selling through distribution, so I want to own customer interface. I like businesses that have multiple revenue streams, so you have product, you have service, you can do financing, and that are capital-efficient. I don’t like businesses that utilize a lot of cash. I like businesses that generate a lot of cash because we’ve got a lot of ideas on how to grow businesses.

I have a real rule…we sold any business that we think somebody can run better than we can. So we sold our motors business. We sold our insurance business. We sold our global exchange business. We’ve sold our backroom sourcing business in India. Any business that I feel like somebody can run better than we can, we sell.8

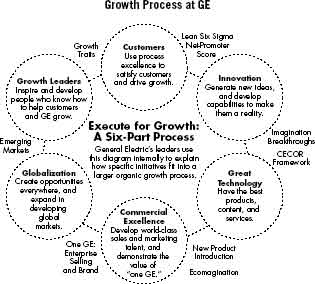

Immelt has created a growth process for GE. These are a set of interdependent processes owned and driven by the CEO. They are judgment-shaping and enabling processes. It is part of his strategy judgment platform. The six-part process as shown in the diagram “Growth Process at GE” is used by Immelt and other GE leaders to teach leaders throughout GE about how growth is generated at GE.

Immelt took several years to evolve his six-part process:

I knew if I could define a process and set the right metrics, this company could go 100 miles an hour in the right direction. It took time, though, to understand growth as a process. If I had worked out that wheel-shaped diagram in 2001, I would have started with it…. But in reality, you get these things by wallowing in them a while…Jack was a great teacher in this regard. I would see him wallow in something like Six Sigma, where easily the first two years were tough…. He’d get different businesses sharing ideas, and everything always crystallized in the end. He was a good initiative driver.9

GE’s Growth Tools10

These are the tools GE uses to drive top-line growth.

- Acquisition Intergration Framework: outlines a detailed process for ensuring that acquired entitles are effectively assimilated into GE

- At the Customer, for the Customer: brings GE’s internal best practices, management tools, and training programs to customers facing their own managerial challenges

- CECOR Marketing Framework: connects innovation and other growth efforts with market opportunities and customer needs by asking questions to calibrate, explore, create, organize, and realize strategic growth

- Customer Dreaming Sessions: assemble a group of the most influential and creative people in an industry to envision its future and provoke the kind of interchange that can inspire new plans

- Growth Traits and Assessments: outline and enforce the expectation that GE’s next generation of leaders will display five strengths: external focus, clear thinking, imagination, inclusiveness, and domain expertise

- Imagination Breakthroughs: focus top management’s attention and resources on promising ideas for new revenue streams percolating up from anywhere in the organization

- Innovation Fundamentals: equip managers with four exercises to engage people in innovation, and prepare them to transform new ideas into action

- Innovation Labs and Tool Kit: support business strategy, product development, and other cross-functional project teams with a variety of resources and materials relevant to innovation efforts

- Lean Showcases: demonstrate the power of “lean” thinking by allowing people to see how cycle times were reduced in a core customer-facing business process

- Lean Six Sigma: puts the Six Sigma methods and tools in the service of a critical goal—reducing cycle times in the processes that chiefly drive customer satisfaction

- Net-Promoter Score: holds all GE businesses to a new standard: They must track and improve the percentage of customers who would recommend GE. The scores are seen as leading Indicators of growth performance; business teams apply lean Six Sigma and other tools to analyze scores and identify and implement improvements

In addition to the six-part process, Immelt has a set of tools that are used to drive the six processes. These tools are levers and drivers for making the process work, such as “customer dreaming sessions” to drive innovation. These are one-to-two-day sessions held at Crotonville with the CEOs and key leaders from a business.

Ram Charan describes Immelt’s dream sessions:

He invites people from one customer industry at a time, usually CEOs and one or two associates for a one-or two-day session in which the conversation and presentations are geared toward what each of the participants visualizes over a long period of time—up to ten years. They discuss the external trends, the root causes of those trends, how they might converge, in what fashion and what the picture might be as viewed from as many different angles as possible, including the customer’s customers, suppliers, regulators, special interest groups and trends in technology.11

Immelt’s job as a leader is to create the platform for GE leaders to make good strategic judgments. He is the social architect of a set of processes to enable that and he is also the head teacher in getting these processes into the DNA of GE.

The Big R&D Judgment at GE

Growth through innovation is Immelt’s number one priority. He does it with innovation projects, and with a massive investment in R&D. He made a strategic judgment to drive the execution of innovation through the use of his personal time and his commitment to new innovations. He describes some of his activities to drive innovation.

We really, totally kind of focus on how do you get new ideas into the marketplace. In GE, we have a process now called imagination breakthroughs that are a hundred projects that have the opportunity of being $100 million in revenue in the next five years. And I am the program manager. I’m the person that makes sure that they’re funded; I help pick who the program managers are; I make sure that the risk and the time horizon can be taken at my level; and really trying to find ways to make size, to make this girth of GE a platform for innovation and not something that’s going to choke off real creativity in the future.12

Judgment Execution Phase at GE

MAKE-IT-HAPPEN STEPS:

Immelt’s big judgment bet on technology depends on solid execution, so he has put in place a number of core execution supports. These include increased capital expenditures for R&D, upgrading the facilities, and opening new satellite R&D facilities around the world in places as far-flung as Germany, China, and India. The most important of all is the way he is forging human linkages between Global R&D and the leaders of the businesses.

Innovation requires people to interact, to be creative together, to brainstorm, and to be able to make their own judgments about what will and will not work. When Noel interviewed him in the fall of 2001, Immelt already knew that he was going to expand GE’s focus and expenditures on R&D. In the same way that Welch expanded Crotonville and increased the focus on leadership at GE, Immelt would make GE’s R&D center the centerpiece of meaningful learning and interaction that would shape the future of the company.

Attendance at Crotonville and leadership development are required for business leaders at GE. All businesses send leaders to programs that are mandated by corporate GE. GE’s business leaders all teach at Crotonville and the heads of the businesses attend Immelt’s four-times-a-year Corporate Executive Council. At these two-day meetings at Crotonville, they meet leaders going through programs and also get action learning teams from Crotonville to report out to them. It is a large part of what makes Crotonville an integral part of the GE DNA.

Immelt made a judgment that all business leaders need to be in the technology game as well. Along the same lines, Immelt made the judgment to require all business leaders and their teams to go to the Global R&D center four times a year and “hang out,” to interact and work with the technology groups there. To make sure that this could happen, Immelt actually built a mini-Crotonville. He built a lodge, a residential facility to house business leaders and their teams in an informal learning environment, right on the campus of Global R&D. The goal is to support informal sustained interaction with the technology colleagues.

Immelt also makes sure to pull all the other GE execution levers. Leaders have technology elements to their strategic plans. Succession planning discussions and judgments are tied into technology and innovation, and budgets must reflect a commitment to technology. One of the hallmarks of GE is this systematic alignment around key initiatives.

One of the most significant judgment execution levers is the GE value system. The judgment to grow organically through technology led to a dramatic change in the GE values. The values that Welch emphasized included speed, simplicity, self-confidence, boundary-lessness, and the four E’s, which in Welch’s words are: “Energy to cope with the frenetic pace of change. Energize the ability to excite, to galvanize the organization and inspire it to action. Edge the self-confidence to make tough calls with yesses and noes and very few maybes, and Execute, the ancient GE tradition of always delivering, never disappointing.”13

Immelt has changed the values to be: imagine, solve, build, and lead. These four values are the ones that he feels will support the right behaviors throughout GE to execute on his growth strategic judgment. It means that all of the hiring and promotions screens at GE ask how well people have done and can be expected to do with regard to these values. Do they have imagination? Can they innovate, and have they done so in the past? Can they solve problems? Have they taken innovative ideas and turned them into solutions for customers? Can they take innovation that solves a customer need and build it into a viable business? And, finally, can they develop and lead others to grow through innovation?

Immelt operationalizes his development of growth leaders as follows. He states:

Our leaders are now trained and evaluated against five capabilities. They must:

- Create an external focus that defines success in market terms

- Be clear thinkers who can simplify strategy into specifications, make decisions, and communicate priorities

- Have imagination and courage to take risks on people and ideas

- Energize teams through inclusiveness and connection with people

- Develop expertise in a function or domain, using depth as a source of confidence to drive change.14

GE spends about $3.5 billion in R&D. Corporate Global Research and Development spends about $500 million of that, focusing on high-end technology, really deep, advanced thinking. The individual GE businesses, which also have their own R&D groups, spend the other $3 billion. The business and corporate R&D efforts work collaboratively to divide up the work based on expertise and need.

Learn and Adjust in the Execution Phase

A key player in Immelt’s execution of his R&D strategy is GE Global’s head of R&D, Mark Little. It is Little’s leadership and the processes he puts together that will greatly influence how key leaders and technologists interact, and ultimately determine how well they are able to create innovations that get commercialized. The success of Immelt’s technology-based strategy depends on this collaboration.

Mark Little describes his responsibility:

I’m the Head of GE Research and Development. I watch out for all the technologists in the company. It’s kind of interesting—GE has about twenty-seven thousand technologists working across our broad businesses. A few short years ago, we had almost no technologists in India or China. Today, 15 percent of our total technologists are in India and China, and we’re rapidly going toward 25 percent. Why do I bring that up? Globalization is real, it’s happening very fast, and we want to tap into the best global brains we can. We’re finding great talented people in these places, and they’re helping us change our business.

But there’s another very real thing. We want to be close to the markets that are emerging in India and China. Over even the near term, I think, they are going to be huge, important marketplaces for us, and we really need to understand how to play there. And having people on the ground thinking about markets is very important for us.

We have things we call “In China, For China,” and “In India, For India,” which are technology plays about developing products for these local markets. So we’re doing this across the entire business.

Little explained to us the processes he was setting up to make sure the technological advances at GE are understood by the people in the businesses and that the unmet customer needs are communicated to the technologists so that they can target their efforts to produce solutions.

The way it’s been done here over time has been a little bit more unstructured than I’d like it to be. So, for instance, you hear Jeff talking about the growth playbook process for GE. We don’t really have such a process here at the Global Research Center, and we’re creating that. So we put together a growth team to work on: How do you generate ideas from the ground up; how do you get them in externally; how do you feed them; and then, how do you pick from them? So we’re putting together a process that’s in sync with GE’s growth playbook process. It’s called Session T. As the businesses build up their growth playbooks, they start thinking about what they need for technology. So we’ve got a well-defined process to do this where the marketing people, the engineering leadership and our scientists get together in what’s called a Session T. And the way that works is, you spend a couple days, typically…first; saying what the market needs. Big picture, idea phase, brainstorming. Then you say, what can we do to develop some technology for that. And they’ll bring forward some ideas to do that. And the output of a Session T is a set of what we might do. The follow-on to Session T is sort out what we can do.

To support this process Little’s leadership role is to energize and engage his R&D technologists in a more productive way. He describes it, saying:

I wanted to get much more engagement from the folks here. There are tremendously smart, well-connected people here, and I really wanted to tap into their brain power and make it a more open process with a lot more debate, rather than having a bunch of smart people pitch their wares out and then having other smart people go into a room and decide what we’re going to do. We’re going to make it a much more open, interactive process.

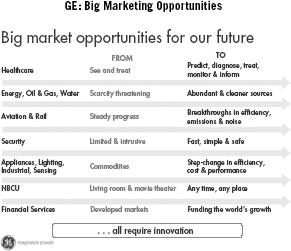

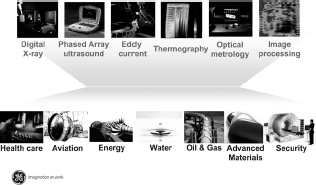

Little wants all of his technology leaders to be able to conceptualize opportunities from the “outside in,” meaning that they will be looking at customer needs and then try to couple them with emerging technology. The chart “GE: Big Market Opportunities” frames some of the opportunities for the GE portfolio of businesses.

This chart is key to how Little teaches his leaders to think not about what we are doing today but where the world is going so that technology and the R&D work execute on Immelt technology strategy.

In order to make the connection with the businesses work better,

Little is setting out to orchestrate a new set of processes. He gave us an example from the Rail Business, which manufactures railroad engines.

You’ll start off with people who represent the businesses feeding ideas for trends that they see to Rail, for which they know they’re going to need more efficient engines. They know they’re going to have a lot of pressure on emissions coming out of our transportation engines. So they’ll start to talk to the people in the laboratory groups about the need for low-cost, efficient, low-emissions transportation technology….

Then you ask the scientists to think about what can you do about that, and they start bubbling up ideas. Then you have the technical people vet those ideas. We have a process that gives people some money to play through the ideas and see whether they can be made to work or not. And if they can, then they’ll bring it forward to another level of decision making, and it all will come together in the thought process.

Immelt’s drive to increase the interaction with the businesses has had a positive emotional impact on both the R&D team and the business leaders, Little says. “People here are unbelievably self-confident and optimistic about what they can do. And the business guys love to come here for that reason, ’cause it’s so refreshing.” The scientists are teachers and learners with the business leaders. Because of the regular visits, the interactions are informal and include receptions and meals as well as opportunities to brainstorm; they are more productive than meetings where the businesspeople and the technologists just push one another on short-term deliverables.

GE Health Care and R&D

The acquisition of Amersham was a key element of GE’s strategy to become a leader in personal medicine. But despite the enormous size of the acquisition, it was not the whole strategy. In fact, the acquisition came after GE technologists had already begun looking at ways to expand beyond GE’s traditional diagnostic imaging business. The acquisition of Amersham furthered and redirected a strategic thrust that was aimed at taking GE more into bioscience. It gave GE a platform from which it could leap into the business. Little describes the course of events:

We’ve got a world-leading diagnostic imaging business. It became pretty clear that there was a lot happening on the biosciences side that would be a very nice companion to that. So they started up a research program here to try to open up some doors for us. And it wasn’t clear exactly what the doors were going to lead us to. But we started up a research center; started hiring some great people in. And then, as we started to think about that whole space, the [Amersham] acquisition came into play. We bought [Amersham], and now we’re building off that. We’ve got tremendously great programs going on. We’re going to change the face of medicine. There’s just no doubt about it.

The health care execution included moving scientists from the UK Amersham home base to the upstate New York labs so that they could work with Little and his team of scientists.

NANOTECHNOLOGY APPLICATIONS

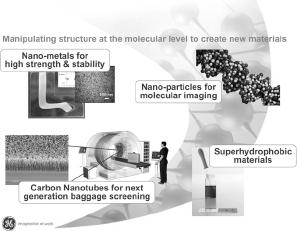

One exciting part of the execution of the Global R&D strategy is looking for new applications for nanotechnology.

You know, people spend billions on nanotechnology, most of it semiconductor that we’re not interested in at all. We care a lot about applications. For example, there’s a lot of nanotechnology that feeds into the biosciences sides, because you want to find very, very small particles that can attach onto things and absorb quickly, and nanoparticles do that. You get material properties that are phenomenal out of nanoscience stuff. We’re doing some fascinating things in lighting with nanotechnology. So it’s just a basic material science that’s very interesting and powerful and spreads across all our businesses.

The chart “Big Swings: Nanotechnology” is one that Little uses to show GE leaders about the potential applications of nanotechnology. The scientists in the lab are busy experimenting with these applications and are collaborating with the scientists in a number of the businesses to find new uses for them. This is one of the ways that Little supports Immelt’s strategic judgment on technology by providing the channels to “make it happen.”

Big Swings: Nanotechnology

In addition to nanotechnology, GE R&D is working on biotechnology. This is where physics meets biology to explore a new paradigm for early health detection. This will range from molecular and digital pathology for in vitro diagnosis, to targeted magnetic resonance contrast agents that make images far more accurate and clear and binders for disease-specific contrast agents.

CROSS BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY APPLICATIONS

One of the most promising aspects of the strategic execution of Immelt’s technology judgment is what is occurring at the Global Research Center (GRC) with cross-business applications. When we visited the GRC we saw examples of this, such as the use of medical imaging technology—CAT scan and MRI—being developed for oil pipeline and refinery scanning systems that might have prevented catastrophes like the BP oil pipeline leak in Alaska in 2006, or the BP refinery explosion in Texas that killed fifteen workers. The chart “Core Technologies: Imaging” shows some of these cross-business applications of technology.

Core Technologies: Imaging

For example, X-ray and imagining technology are being used to do preventive maintenance assessment with oil and gas pipelines; other imaging technologies are being applied to security and aviation. The GE advantage is multitechnologies across a multibusiness portfolio. If GE can execute their technology strategic judgment, they have an unmatched portfolio on size, breadth of technology, and breadth of businesses.

Jeff Immelt has made some very bold, bet-the-company strategy judgments. Initially, they have not paid off in terms of stock performance. In early 2007 the Financial Times summed up his challenges:

Despite having long commanded a place in the pantheon of the world’s most admired companies, the US industrial group enters the year having to prove its worth to the capital markets. GE shares have underperformed the S&P 500 index in the past six years…the challenge facing the company is disarmingly simple to make a convincing case that its strategy to drive profit growth across its sprawling portfolio warrants a high stock market valuation…the stakes are such that if 2007 does not prove a breakout year, there is a risk that capital markets may turn one of the following ones into GE’s break-up years.15

As the quote indicates, Immelt is on the line in 2007 for his GE strategy judgments. He has spent five years repositioning GE for future growth; now he needs to demonstrate that his strategic judgments will yield the promised results. His is a work in progress. He has dropped businesses from the portfolio, a never-ending process, and is adding new ones through acquisitions and organic growth to create the GE future engines of growth. Five years into the transformation, his judgments were showing clear evidence of being rewarded in the stock market. Jeff Immelt states:

To be a reliable growth company requires the ability to conceptualize the future. We are investing to capitalize on the major growth trends of this era that will grow at multiples of the global GDP growth rate. We are using our breadth, financial strength, and intellectual capital to create a competitive advantage.16

Below is a summary of how Immelt explains his strategy judgments to the world, both internally to GE and externally, including Wall Street, the press, and key stakeholders. He is relentless in sharing his storyline and relentless in driving the strategy execution.

SUMMARY OF IMMELT’S STRATEGY JUDGEMENT FOR GE

The Transformation of the GE Portfolio of Businesses

- Focus on a faster-growing, higher-margin set of businesses is paying off.

- Since 2002, completed approximately $80 billion worth of acquisitions of faster growth. High margin business and close to $40 billion of dispositions of slower-growth, lower-margin businesses.

- Delivering consistent double-digit earnings growth of 10 percent 2001–06.

- Two straight years of organic revenue growth of two to three times GDP.

- Two straight years of expanding margin rates and increasing returns.

- Global revenue almost doubling from $40 billion in 2000 to $75 billion in 2006.

- Higher-margin service revenue doubling from $16 billion in 2000 to $30 billion in 2006.

- Net income almost doubling since 2000.

The Transformation of the Portfolio and the Investment in Technology Position GE to Capitalize and Key Growth Drivers

- Changing demographics

- Digital connections

- Liquidity

- Global infrastructure growth

- Emerging markets

- Ecomagination—clean energy