10

CRISIS AS A LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY

Leaders Who Make Good Judgments Are Prepared in Advance for Crises

Leaders Who Make Good Judgments Are Prepared in Advance for Crises

- They have built aligned and trusted teams.

- They have clear Teachable Points of View and storylines.

When a Crisis Arrives, Winning Leaders Respond Immediately

When a Crisis Arrives, Winning Leaders Respond Immediately

- They engage the appropriate people with the needed knowledge.

- They mobilize their team of aligned leaders for quick execution.

Crises Provide Leadership Development Opportunities

Crises Provide Leadership Development Opportunities

- Leaders role-model behaviors necessary for success.

- An explicit teaching process keeps everyone focused on critical issues.

The most important task of an organization’s leader is to anticipate crisis…perhaps not avert it, but to anticipate it.

—Peter Drucker, Managing the Non-profit Organization: Principles and Practices1

Why are some leaders better equipped to deal with crises than others? Even when hit with totally unpredictable events, why do some leaders do a better job of responding? Why are some of them even able to turn organizational crises into leadership development opportunities?

The answer is because they anticipate crises. They aren’t psychics. They can’t see into the future and predict seemingly random events that are going to strike two days or two years hence. But they clearly understand that some crises are going to come down the pike, and they prepare themselves and their organizations to respond effectively and efficiently when they do. These leaders know that in order to survive crises, and perhaps even come out ahead because of them, they must have three things:

- 1. An aligned and highly trusted team;

- 2. A Teachable Point of View and storyline for the organization’s future success;

- 3. A commitment to developing other leaders throughout the crisis.

David Novak, CEO of Yum! Brands, and Phil Schoonover, CEO of Circuit City, are two leaders who have successfully navigated their organizations through several crisis situations. Both Novak and Schoonover do three things simultaneously. They

- 1. Effectively, in real time, deal with their crises.

- 2. Mobilize, align, and engage the right social network of leaders in their organizations by tapping their brains and their emotional energy to handle the crises.

- 3. Focus explicitly on developing the leaders engaged in the process, taking the time to teach and coach in real time.

Leaders who succeed in crises are able to do so because they work on developing their own capabilities and on building them into the fabric of their organizations. The conventional wisdom regarding crisis management and communication, basically, nets out to be good public relations advice. It includes such things as (1) preparation of crisis contingency plans, (2) analysis of the crisis and public perceptions, (3) identification of the relevant audiences, (4) repairing a tarnished image, (5) suggestions for effective ways to repair the organization’s image.

All of these are reasonable actions, but they do not address how to fundamentally help the leader deal with the crisis judgment process in a way that furthers the organization’s storyline, builds for the future, and also develops a broader social network of leaders better able to handle future crisis judgments.

David Novak has successfully made a number of crisis judgments, including responding to the avian flu in China, which was affecting the perception of the safety of the KFC food supply chain, and the E. coli outbreak first believed to be associated with green onions at Taco Bell that resulted in sixty-three confirmed illnesses. Both of these crises were serious threats to Yum!’s businesses. In the Taco Bell case, it appeared that the unit’s green onions were the source of E. coli causing illnesses in consumers. The source of the problem was never completely confirmed, but Taco Bell immediately ordered the removal of all green onions from its fifty-eight hundred outlets nationwide as a precaution after samples initially tested positive for E. coli. Subsequent testing ruled out green onions as the source. The CDC later determined that lettuce may have been the more likely source. Taco Bell replaced all its lettuce across the Northeast, and switched its regional produce supplier as an added precaution.

Novak has repeatedly exercised good crisis judgment for the organization while simultaneously developing his leadership team’s capacity to handle future crises. In his business, most crises are likely to be around the safety of the food supply chain. He has a very clear Teachable Point of View for Yum!, and it is played out in his storyline for where the company is headed; this is the context for his crisis judgments.

Phil Schoonover faced an earnings crisis with the collapse of the pricing for flat panel TVs in the holiday season of 2006. Wal-Mart and Costco brought down the price of a 42-inch plasma flat screen TV from a 2005 price point of about $2,200 to $999 in one year.

The revenue plans for Circuit City’s holiday season were based on old assumptions about price and profitability, as were its full-year projected profits. The holiday season is the major contributor to Circuit City’s full-year profits. Because they were in the midst of a turnaround situation, they were much more vulnerable to price cuts than their much bigger and stronger key competitor, Best Buy.

The result was that Schoonover’s team had to call a “time-out” and do a radical “redo” loop around the execution of the longer-term strategy for Circuit City. They had to radically reduce expenses while accelerating growth. This was done in an engaging process where eleven teams in sixty days worked on special “crisis” projects three days a week, plus managed their day jobs during the busiest season of the year and came up with ways of keeping Circuit City delivering on its Teachable Point of View and storyline. While working on the crisis, they also were coached and taught by Schoonover and the top team to be more effective leaders.

By mid-2007 the Circuit City crisis was still a work in progress, as reported by the hometown press:

Circuit City Stores Inc. continues to have nagging health problems as it nears its 60th birthday.

But the Henrico County–based consumer electronics retailer seems to be taking steps that could put it on the road to better shape.

Sales have grown only slightly in recent years. Profit margins have shrunk. Earnings are unstable. In less than a year, its stock price has been sliced in half.

Circuit City has opened a net of 38 U.S. stores since 2002 and is debating the sale of its Canadian operation. Rival Best Buy Co. Inc. has added nearly 350 stores during the same period, has a strong foothold in Canada and is expanding into China.

After posting a net loss for the fiscal year, things got worse for Circuit City when the chain said last month that it expects a bigger operating loss—as much as $80 million to $90 million—than it had forecast for its fiscal first quarter, which ends May 31. The company said sales fell “substantially below-plan” in April.

Philip J. Schoonover, Circuit City’s chairman, president and chief executive, knows he has his work cut out to get a grip on costs, boost sales and increase profitability.

“We’re at the beginning of act two of a three-act play,” Schoonover said last week. “Despite the choppiness in our near-term performance, we are staying true to our long-term strategy.”2

YUM! BRANDS

David Novak is a veteran at crisis management. He is a seasoned leader who knows that crisis judgment starts with good people judgment. He painfully learned this lesson is his early days as CEO at Yum! Brands. As the company, then called Tricon Global Restaurants, was being spun off from PepsiCo, he compromised on a key people judgment, the CFO, and almost created a crisis for the company.

Novak has a clear Teachable Point of View and storyline for the company. However, when he was just taking over, he felt pressured to have a successful launch. He made a compromise that he later regretted. He told us:

One of the worst leadership decisions I’ve made was hiring a CFO who supposedly brought expertise to the table that we thought we may be lacking. He was president of a competitive company and had a good pedigree. But my gut told me that this guy really wouldn’t be a good cultural fit. He lacked the leadership style that I’ve found motivating in others. He was smart and PepsiCo thought he had the right technical skills for our new public company. It was in the very early stages of our company and I agreed to compromise on my decision. We had very little time to take our company public and with that time pressure, we didn’t do enough homework on our own how to explore how he’d fit in with our other teams. I should have trusted my gut reaction and taken the time before making the call.

PepsiCo hadn’t given us a lot of time to staff with the right people. I was pressured on time. And we were looking for an experience that we didn’t necessarily have. And those two things really drove, I think, a very poor decision.

The result was he got the CFO to resign in order to avert a crisis during a critical time for the organization.

AVIAN FLU CRISIS IN CHINA

This experience bolstered Novak’s determination to have a very clear approach to crisis judgment. First and foremost he says it is critical at Yum! “to have process and discipline around what really matters and keeps you out of crises.” But even with effective crisis prevention, and all the discipline on the planet, some crises can’t be prevented. In 2005, for example, KFC in China had to cope with the avian flu scare. Many Chinese were afraid to buy and eat chicken, and partly as a result fourth-quarter profit dropped 20 percent. However, within months KFC sales rebounded largely because of how Yum! and KFC handled the crisis.

Preparation Phase

SENSE AND IDENTIFY

Novak and his team sensed and identified the need to make a crisis judgment regarding the sale of chicken at Yum!, most important in KFC stores in China, very quickly. As the World Health Organization (WHO) and the media chronicled the avian flu epidemic in Asia, the judgment was how to support the brand and keep selling chicken in the face of the flu scare.

FRAMING AND NAMING

The key was the framing and naming of the judgment. For Novak and his team the framing was that “people need education and understanding” regarding the safety of chicken at KFC. Sam Su, the president of Yum! Brands International Greater China, faced the reality of avian flu in his territory and then started educating the public on the myths and realities associated with the disease. He explained that chicken meat served at KFC outlets was safe because bird flu could not be spread via thoroughly cooked chicken or egg products. He also explained that authoritative organizations, including WHO, had shown that high temperature is one of the most effective ways to kill avian flu virus and that all KFC chicken is processed above the required temperature. This teaching was aimed at mobilizing and aligning both internal and external stakeholders so that the judgment call to keep selling chicken and defend the brand could succeed.

MOBILIZE AND ALIGN

The Yum! corporate team provided materials to all the store managers and staff worldwide so that they could answer questions and concerns of customers.

The Call Phase

The judgment call that was made by Novak, Sam Su, and team was to keep selling chicken in China and around the world by making sure that customers knew and understood they were safe. The way to do this was to keep teaching the community about avian flu and the food chain.

The Execution Phase

There were many actions taken to drive the execution of this crisis judgment. These included a preemptive campaign of putting small stickers on the lid of every KFC bucket, assuring customers that the chicken was rigorously inspected and thoroughly cooked, quality assured.

Novak and his team learned and adjusted as they went along and ultimately proved that they had exercised good crisis judgment, as the brand is doing fine and KFC is selling record amounts of chicken in China.

ANOTHER CHINA CRISIS: RED DYE

In addition to the avian flu crisis Yum! got hit with another crisis in China when a red dye used there was linked to cancer. Profit again plunged 30 percent until they worked out a solution. “A food safety issue can happen in any country,” Novak told us. “We have to use education to insulate ourselves.”

In talking about the food dye crisis Novak made his role as CEO clear.

I trusted Sam Su (the local CEO). We gave him coaching, we gave him ideas but we knew he knew the Chinese government, he knew the Chinese media, he knew the Chinese consumer better than us, and he handled it extremely well…my job was to let him know that we are 100% confident behind him…. I sent a letter to the Chinese team and said we’ll come back, this is a short-term thing, I appreciate all the hard effort…. I felt that my big job as a leader was to understand what was going on there, provide whatever coaching I could…and provide support.

Novak reflected on another lesson: Even though not one customer was hurt, he made it clear that the red dye crisis never should have occurred. It should not have been in their supply chain. He told us, “No one ever got sick or would ever get sick by what was in the supply chain. But it shouldn’t have been in there. It wasn’t an approved ingredient.”

TACO BELL GOOD CRISIS JUDGMENTS

As Novak predicted, the food supply chain created another crisis, this one the E. coli outbreak in the United States linked to Taco Bell. Once Novak identified the need for crisis judgment, he followed his well-developed approach. Based on the strong Teachable Point of View and a storyline that builds customer mania and growth, the team framed and named the judgment around how to support customers’ safety and therefore the brand. The judgment to stop using any green onions in all 5,800 stores was how this judgment was executed, along with constant communication with the staff and the public.

The crisis judgment success led Novak to write in his 2006 annual report letter:

I’m particularly proud of the Taco Bell team for weathering a produce supply incident impacting our restaurants in the Northeast during December. Brands can go either forward or back on how they deal with a crisis, and our customers told us we did a very good job. As we move ahead, Taco Bell will be leading the industry by requiring our suppliers to test produce at the farm level, in addition to testing already being done by the produce processors. This additional precaution will enhance our stringent food safety standards for all our brands and give our customers added assurance that our produce is as safe as possible.”3

Novak’s Teachable Point of View on Crisis Judgments

David Novak personally teaches his leaders how to deal with judgments in times of crisis. He has a very clear Teachable Point of View on crisis leadership: First, “what you don’t do is try to solve a crisis by jumping to the wrong solution too early. Seeing the total landscape and trying to instill the need to do that is important.” This sets the stage for proper framing and naming, which takes some cool, cognitive thinking, not emotional knee jerking.

Second, it is important that the mobilizing and aligning be done by the right people. Rawl at Exxon missed this totally when he distanced himself from the Valdez crisis. Novak told us:

You have to look to your senior leadership to get those crises…. When you’re in a crisis, you don’t hand off the problem to the rookie, because rookies haven’t gone through it before. You show the rookie how to go through it when they have to go through it. You don’t delegate crisis management. You’re in there, you’re helping people figure this out. When you do delegate, you delegate to people that know a heck of a lot more about it than you.

No matter what they do, Novak and his team will undoubtedly face more crises in the food supply chain. And there will probably be other crises caused by external catastrophes or by internal errors. What Novak is doing is developing other leaders who can drive his Teachable Point of View and in turn develop others who can make good crisis judgments. His last piece of advice to us on this matter was this important insight:

The worst thing that can happen in a crisis is to have some jerk sitting there saying, “We should have done this, we should have done that.” You don’t have time at that point to say, “We should have done this or should have done that.” At that point you’ve got to help. It comes down to people. If you have people that you trust and believe in, you can handle crisis judgments. If you do not, you work with them, you coach them so they’ll solve the problems and handle the crises. If you don’t, you better get some different people.

PHIL SCHOONOVER AND THE CIRCUIT CITY CRISIS

Philip J. Schoonover took over as CEO of Circuit City in March 2006. Schoonover had been a key leader at Best Buy. He helped Best Buy’s turnaround in the mid-1980s, led the building of its service business, and helped lead the transformation from product-centric to customer-centric, so he was a veteran in large-scale retail transformation. Still, he was taking over a company that had a number of serious problems. While the company had once been number one in its industry, it was then left to flounder and was underinvested both in terms of stores and human capital. The first thing Schoonover did was get a team in place and develop a Teachable Point of View and storyline for the future.

The transformation hit a serious road bump. After the stock shot up to $40, reflecting positive expectations for Schoonover’s transformation plans, the wheels came off. The competitive environment changed, and Schoonover was dealing with a stock price that in the first half of 2007 was down to $16. Less than one year into the turnaround, Schoonover was faced with an even tougher environment than imagined.

This raises an important, albeit somewhat obvious, point about crisis judgments. While making the right ones at critical junctures can literally save a company so that it may live another day, successful crisis judgments do not guarantee the future success of an organization. The Circuit City/Schoonover case is a prime example of how a CEO can make and execute one excellent crisis judgment and execute it to great precision, only to face other, even greater problems in the months ahead.

In the fall of 2006, Schoonover had been Circuit City CEO for about eighteen months. In baseball terms, that put him at about the bottom of the first inning. That is too little time to measure the success of a leader of a complex company like Circuit City (GE’s Jeff Immelt has had more than five years at the helm, and that, too, is not enough time to measure his effectiveness).

There have been some painful lessons along the way. One leadership judgment that Schoonover made in March 2007 was to both shrink and grow simultaneously. He had to do layoffs in one part of the business while simultaneously adding head count to the Firedog services organization and other growth platforms. The judgment to make the cuts was good; the PR was not good. He got slammed in the press for cost cutting, something he knew was the right thing to do. From his point of view it was a necessary turnaround tactic, not unlike what Jack Welch did in the mid-1980s when he laid off more than one hundred thousand workers, garnering the “Neutron Jack” moniker that he detested (Noel was head of GE’s Leadership Development at the time).

Even though the move set off a firestorm in the media, Schoonover is clear that he would make the same decision today, although he would frame it differently. Cost-cutting is seldom praised in the press, but it is often a necessary and critical step in executing a successful big-company turnaround.

What he learned was the importance of shaping and controlling the overall storyline that is part of a rebuilding for the future, a painful but necessary step in his journey. As controversial as that decision might have been, it shouldn’t detract from Schoonover’s handling of the flat-panel pricing crisis. His successful navigation of this crisis is a textbook example of how not only to weather a storm, but also how to build a leadership capability for the future.

When prices collapsed in flat-panel TVs, Circuit City’s earnings, which depended largely on the 2006 holiday season, were headed for disaster, as were the plans for 2007 and 2008. Rather than attempt to respond as the “lone ranger” crisis leader, Schoonover created a crisis judgment platform for eleven teams of leaders at Circuit City. He led it; and it enabled his team to make the short-term crisis judgments needed so as to be able to drive the longer-term Teachable Point of View and storyline for Circuit City.

Circuit City Being Prepared for Crisis

The most important preparation for a crisis is the fundamental work on developing a Teachable Point of View and storyline for the organization, as these provide the context for crisis judgments. Schoonover led an effort in the first half of 2006 involving hundreds of top leaders at Circuit City to develop a long-term strategic plan and a TPOV and storyline. The top leaders then had to engage thousands in leader/ teacher workshops to drive the new Teachable Point of View throughout Circuit City.

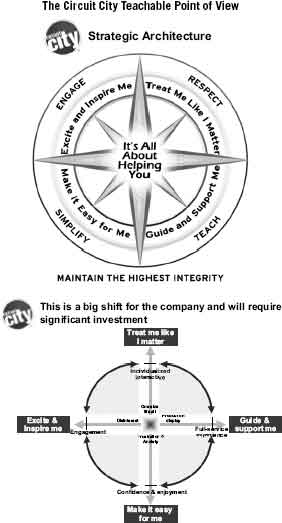

In August and September 2006, the top two thousand leaders taught several daylong workshops to thousands of employees throughout the stores, including the forty-five thousand part-time associates. These workshops were designed to teach everyone the storyline for the future of Circuit City. The chart “The Circuit City Teachable Point of View” is what Schoonover and the top team developed. It lays out the basics of the Circuit City Teachable Point of View. It reflects Schoonover’s belief that what is good for associates is also what helps customers. Both groups need to be treated like they matter, be supportive, be inspired and excited, and have things made easier. Schoonover and his team together crafted that into a storyline for the future. They described what the stores and Web experience would look like, how the new Firedog services would be different and better than the competition, what the associates would be doing with customers, and how Circuit City would perform competitively.

One powerful exercise for helping the team get the narrative developed was to have Schoonover and each of the top team write a narrative, a story, taking place two years in the future, that they would each like to see it on the cover of BusinessWeek. These stories had to include a vision for where the company was going to be in two years in terms of sales, profits, organization, performance versus competitors, as well as a blueprint on how Circuit City would transform itself from 2006 to 2008. The stories had to capture the leadership, the culture, and the challenges along the way, and they had to be living narrative stories, not PowerPoint presentations.

After an hour of writing, each team member read his or her story to the group and the group then listed the themes that were in each story. Generally, there were about ten critical elements, including the people who were running what part of the company, problems encountered along the way, expected performance and stock price, what stores looked like, how the company faired versus the competition, and so on.

The process ended with the team reviewing where they were aligned and not aligned. In situations where they were not aligned, they talked about what they would do to get there. This process of aligning leaders around a common Teachable Point of View and getting everyone to take a role in making it happen was cascaded throughout the company, as was the development of a future storyline for every associate in every part of the organization.

For example, the head of an individual Circuit City store had to personalize the Circuit City Teachable Point of View for that store and had to be able to have a future storyline for his or her associates. Noel facilitated this process and can attest to the total lack of focus on the potential for a price collapse driven by an aggressive competitive action on the part of Wal-Mart, Costco, or others. They did not anticipate the severity of the problems created by what they later called the “perfect storm.”

The Circuit City Crisis Judgment Process

PREPARATION PHASE

Sense and Identify: The Circuit City top team failed on the early warning. They were overconfident on their assessment that they had another year before there would be a pricing problem in flat panels. During the summer of 2006 they rallied all forty-five thousand associates, charging them up to win in the holiday season through their flat-panel sales. There was no discussion on the potential of Wal-Mart raining on their parade with a price war. This was vintage “boiled frog” behavior: letting the changes in the environment stay below the threshold of awareness until the organization was thrown into crisis, just like what happened to Michael Dell.

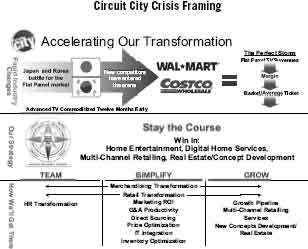

Frame and Name: Once they got slammed, Schoonover responded quickly. The chart “Circuit City Crisis Framing” is the Schoonover framing and naming document that he used to teach his organization about the crisis in the context of where the company was headed. He wanted to make sure that he had a very clear Teachable Point of View for all of his leaders. He taught this slide to thousands of Circuit City staff in town hall meetings so that they all understood what the top team was setting out to accomplish. His team and teams of leaders at all levels used the slide to teach the context for the crisis judgments that Circuit City was having to tackle.

The top third of the slide taught associates about the rapid change in the environment that precipitated the crisis. There was overcapacity of flat-panel televisions in Japan and Korea, and that bloated capacity gave new competitors, namely Wal-Mart and Costco, a cheap supply of flat panels to sell at rock-bottom prices. The example made earlier makes the point: suddenly, $995 42-inch high-quality flat panels became available at Wal-Mart in November 2006—the same televisions that a year earlier sold at Circuit City for $2,400. When the prices dropped below $1,000, havoc was created with the Circuit City business model, which was dependent on sales of extended warrantees and bundles of accessories such as extra speakers, cables, furniture, and brackets to mount the TVs. The lower price for the TV also reduced what customers were willing to pay for these peripheral items. Thus, the “perfect storm” was created at Circuit City, and the company had to deal with a new strategic inflection point that threatened its existence.

The chart basically makes the case that the Wal-Mart and Costco disruption of the market due to overcapacity drastically cut pricing—and in turn margins and average ticket (bundle of products and services sold) dropped precipitously at Circuit City. Schoonover reinforced the message that the crisis is not altering the Circuit City strategy; in fact, it is driving an acceleration of the strategy. He used the metaphor of climbing Mount Everest and having to face an unexpected blizzard. He said: We are unwavering in our vision of scaling the mountain. However, we have to deal with the crisis in that context.

The bottom of the chart lists the projects that will accelerate Circuit City’s transformation. Schoonover mobilized and aligned eleven teams of Circuit City leaders and gave each team a clear charge as to what they needed to come up with in a sixty-day period.

The teams were made up of executives from different functions with responsibilities for important day-to-day running of the business from merchants, to finance, to human resources, to retail and IT (information technology). Every one of the eighty members of the “Acceleration Initiative” teams were told that they would continue to do their “day job” while also working three days a week on the “Acceleration Initiative” projects. Tuesday through Thursday were the days blocked out from 8 to 5 for work on the crisis “Acceleration Initiative” projects.

War rooms at the headquarters in Richmond, Virginia, were set aside for each team so that they could have a “home room” and they could also be in easy touch with other teams, as many of the issues cut across more than one team. Each team had a leader from Schoonover’s senior management team who met with the teams every week, multiple times. Schoonover, as CEO, was the overall team leader and he blocked his calendar to spend every Thursday visiting each team to help them and provide whatever coaching was required.

The projects were a mission critical to helping Circuit City get out of the crisis and back to executing its strategy. Each “Acceleration Initiative” was carefully framed and the deliverables were specified in writing to each team. The chart “Acceleration Initiative Transformation Teams” shows how several of the projects were framed for the teams. Note the clear expectations and specifications. A great deal of work went into the framing of each project, all personally led by Schoonover.

Acceleration Initiative Transformation Teams

1. RETAIL TRANSFORMATION TEAM

DELIVERABLES

The teams will have 6 working weeks with 2 touch points along the way. The process will culminate in a 2-day commitment process. As you scope deliverables, ensure that the action items encompass a 3-year view, 1-year operating plan, and 100-day action plan. Review the questions below, and then try to fill in specific deliverables on the table.

The team will develop a comprehensive business plan that will include the following:

Sales, General, and Administrative Expenses: Benchmarking and Optimization

Sales, General, and Administrative Expenses: Benchmarking and Optimization

Review and benchmark all SG&A (fixed and variable) by functional area throughout the retail organization

Review and benchmark all SG&A (fixed and variable) by functional area throughout the retail organization Geographic alignment and consolidation of the Regions and Districts

Geographic alignment and consolidation of the Regions and Districts

Operational Excellence

Operational Excellence

Field organizational structure/span of control; leaders as teachers

Field organizational structure/span of control; leaders as teachers Corporate (retail) organizational structure

Corporate (retail) organizational structure Store standards

Store standards Systems and processes for improved execution of retail fundamentals including SOP compliance process and reporting

Systems and processes for improved execution of retail fundamentals including SOP compliance process and reporting Next wave of SOP refinements and implementation

Next wave of SOP refinements and implementation Gatekeeper responsibilities and communications

Gatekeeper responsibilities and communications P&L management process and reporting

P&L management process and reporting Clear and balanced goals (key performance indexes): Associate, Customer, Financial, Growth

Clear and balanced goals (key performance indexes): Associate, Customer, Financial, Growth

Workforce Management

Workforce Management

Task management (time studies and scheduling)

Task management (time studies and scheduling) Labor Optimization

Labor Optimization

- Labor standards development

- New scheduling tool for forecasting, budgeting, scheduling, and reporting

- Labor planning software selection and implementation

Stratified store management solutions

Stratified store management solutions Full floor capability, earned hours capability

Full floor capability, earned hours capability Performance management system—KPIs, tools, training, implementation

Performance management system—KPIs, tools, training, implementation Training and certification

Training and certification

What must the project team deliver to complete a 3-year validation of the financial/operational targets?

Value target key elements of the three major work streams (SG&A, Operational Excellence, and Workforce Management)

Value target key elements of the three major work streams (SG&A, Operational Excellence, and Workforce Management) Determine hurdle rate

Determine hurdle rate Forecast steady state benefit

Forecast steady state benefit Identify investment (3rd party costs and Circuit City incremental)

Identify investment (3rd party costs and Circuit City incremental)

What must the project team deliver to create a 1-year operational plan with budgeted financial impact?

- Develop a Business Plan:

Clear and compelling mission and vision

Clear and compelling mission and vision

- Problem we’re trying to alleviate

- New value proposition

A clear, actionable agenda including all strategies and plans

A clear, actionable agenda including all strategies and plans

- Customer and associate viewpoint at the top

- Process capabilities

- Infrastructures

- Org structure—field and retail SSC

- Roles and responsibilities

- Compensation models

- Measurements, objectives, and incentives aligned with the key financial outcomes and North Star

- Learning transfer and coordinated metric development with current Team/Simplify work

- Lab and pilot selection, support model

- Milestones

- Team RASI

- Enterprise support requirements; cross-functional business rhythms

What must the project team deliver to create a detailed 100-day implementation plan?

Identify the priorities and sequence of key deliverables—draft the first phase of the plan (100 days) with clearly identified GRPI

Identify the priorities and sequence of key deliverables—draft the first phase of the plan (100 days) with clearly identified GRPI

2. MARKETING RETURN ON INVESTMENT TEAM

TARGET

As we develop our 100-day, 1-year, and 3-year plans, we will do so with the following issues in mind. What must the team deliver to complete a 3-year validation of the financial/operational targets?

The project team will need to identify “best in class” performance as a benchmark. This will likely be within our segment of retail, and will need to be a multichannel view of all media spent.

The project team will need to identify “best in class” performance as a benchmark. This will likely be within our segment of retail, and will need to be a multichannel view of all media spent. The team will need to set growth rate goals for improvement.

The team will need to set growth rate goals for improvement. We will need to balance needed improvements in process and tools with balance sheet–driven investment capability.

We will need to balance needed improvements in process and tools with balance sheet–driven investment capability. We have set a preliminary goal of $40–$60 million incremental margin contribution in three years.

We have set a preliminary goal of $40–$60 million incremental margin contribution in three years.

What must the project team deliver to create a 1-year operational plan with budgeted financial impact?

Scope achievable increases in print gross margin return on assets employed (GMROAE) for f/y ’08.

Scope achievable increases in print gross margin return on assets employed (GMROAE) for f/y ’08. Scope increased vendor contribution to marketing plan over and above conventional coop/market development funds collections.

Scope increased vendor contribution to marketing plan over and above conventional coop/market development funds collections. Scope a basic multimedia optimization modeling process that will enhance our media balance.

Scope a basic multimedia optimization modeling process that will enhance our media balance. Scope a usable media spend allocation process across all channels.

Scope a usable media spend allocation process across all channels.

What must the project team deliver to create a detailed 100-day implementation plan?

Determine current baseline for spending and measure current ROI. This will enable us to track and measure the incremental return from the initiative.

Determine current baseline for spending and measure current ROI. This will enable us to track and measure the incremental return from the initiative. A comprehensive spend plan for f/y ’08 that has the flexibility built in to leverage process improvements as well as analytical and operational learnings as we move through the year. We do not want to find ourselves “smarter” and better able to invest our marketing dollars later in the year, only to determine that we are unable to redeploy any funds.

A comprehensive spend plan for f/y ’08 that has the flexibility built in to leverage process improvements as well as analytical and operational learnings as we move through the year. We do not want to find ourselves “smarter” and better able to invest our marketing dollars later in the year, only to determine that we are unable to redeploy any funds. We must create a compelling vendor (as well as analyst) presentation for the Consumer Electronics Show in January to solicit both incremental funding as well as cooperation and flexibility from our vendors.

We must create a compelling vendor (as well as analyst) presentation for the Consumer Electronics Show in January to solicit both incremental funding as well as cooperation and flexibility from our vendors. We must create and deliver a new process map for Integrated Promotional Planning that will be in effect by March 1 to impact Q2 “go to market” strategies and spend.

We must create and deliver a new process map for Integrated Promotional Planning that will be in effect by March 1 to impact Q2 “go to market” strategies and spend.

What other deliverables can the team accomplish?

New process map for Integrated Promotional Planning.

New process map for Integrated Promotional Planning. New analytical tools for merchant ad planning.

New analytical tools for merchant ad planning. New accounting procedures for joint vendor/Circuit City promotional funds.

New accounting procedures for joint vendor/Circuit City promotional funds. Goal setting for promotional effectiveness for 1 and 3 years.

Goal setting for promotional effectiveness for 1 and 3 years.

3. EXPENSE REDUCTION TEAM

DELIVERABLES

Review outsourcing potentials in the following areas

Imaging

Imaging Accounts Payable

Accounts Payable Meetings

Meetings Relocation

Relocation Property Management

Property Management Store Planning

Store Planning New Store Setup

New Store Setup Excess Property

Excess Property Benefits

Benefits

ORGANIZATIONAL REALIGNMENT

Meetings & Travel

Meetings & Travel Store construction & new store setup services

Store construction & new store setup services Intertan

Intertan

- Procurement

- Real Estate

- Accounting

- Logistics & Distribution

- Store Maintenance

PROCUREMENT SAVINGS

Meetings

Meetings SOP—Travel

SOP—Travel Cell phones (SOP)

Cell phones (SOP) Fixtures (Store in a Box)

Fixtures (Store in a Box) Stores & store support center supplies

Stores & store support center supplies Benefits

Benefits Legal

Legal Aircraft

Aircraft

POTENTIAL BARTERING CANDIDATES

Travel & Meetings

Travel & Meetings Excess Inventory

Excess Inventory Advertising

Advertising

LEASES

Review (Possible Closings)

Review (Possible Closings)

Mobilize and Align: This was a unique aspect of what Schoonover did. As the top team was working with the teams throughout this period, they were coaching and motivating the teams. They were looking for connections between the teams. Simultaneously Schoonover said that this was not just about “crisis” management; the process was also about developing each of the participants as leaders. This was a leadership and organizational capacity-building activity.

He wanted the Circuit City values role-modeled throughout and invested in team building from the start, teaching new skills for team effectiveness, project management, and change leadership. This was an opportunity for growing leaders and simultaneously transforming the company. Schoonover made sure to allocate both time and resources to agendas, crisis management, and leadership development. A multiday workshop was run at the front end of the process to build the teams, to set learning objectives for each member of the eleven teams, and to prepare them for the sixty-day journey to develop crisis judgments and become better leaders.

Judgment Calls

At the end, Schoonover led a highly interactive process that engaged all the team members and the senior team as he made the final judgment calls on the recommendations. In most companies that have teams work on recommendations, the teams make recommendations to a top team who listens, questions, and then tells the team they will get back to them (which may or may not happen).

In the case of Circuit City, at the end of the sixty days, the teams joined with Schoonover and the top team as throughout the judgment process. Schoonover’s goal was total transparency of the decision-making process in each of the eleven areas. He and the top team would make their judgment calls in a “fishbowl” with the participants from the eleven teams in the room and watching.

This final phase of making the judgment calls on the projects came after a very carefully orchestrated multiday process of mobilizing and aligning all the participants and the top team. This process had all seventy “Acceleration Initiative” participants influencing the final judgments along with Schoonover and the top team. In order to make informed inputs into the judgments, every “Acceleration Initiative” participant was required to read all the reports and recommendations before coming to the multiday judgment-making session.

Making good judgments requires discipline and homework. One of the requirements of all the leaders in the final process was that everyone come prepared, meaning that all eleven reports are read by everyone, with written notes and ideas for improvement ready for discussion. This then sets the stage for an interactive problem-solving process to enable the leadership team to better make good judgment calls on the recommendations or modify them in real time with the top team. This is in contrast to the all-too-often case where no one has done the prereading, there are no notes or ideas coming into the session, and the meeting ends up in a “show and tell mode” without engaging the brain power, ideas, and commitment of the almost hundred leaders who were in the “Acceleration Initiative” process.

The process steps for each team were followed in an extremely disciplined and time-bounded fashion.

- REPORT REVIEWS: Three days prior to the setup for “judgment calls,” reports were distributed that everyone was asked to read and be prepared to give their input. A workshop with the CEO, the top team, and participants was held, and the judgment process for each team lasted three hours apiece. The room was set up as a big workshop with six people at a table; the top team and all of the “Acceleration Initiatives” participants were randomly assigned. One team at a time went through the process, which had a very disciplined set of steps.

- TEAM REPORT OUT: Each team had twenty minutes to present their recommendations to the total group (everyone had already read the reports so this was as a reminder and reinforcer).

- INDIVIDUAL PREJUDGMENT RATING (10 minutes): Everyone in the room including the CEO filled out a written report. First, on a 1-to-10 scale rating the recommendations (1 = can’t support it at all, 10 = totally support it; no changes required). Second, if the report did not get a 10, then what specific changes were needed for “my support.” Last, how does this relate to other projects.

- TABLE DIALOGUE (45 minutes): Each table has a facilitator who starts by listing names and numbers: How did each of the six leaders rate the recommendations? That helps calibrate where each person at the table is vis-à-vis the recommendations (someone who is a 9 is thinking marginal changes whereas someone who is a 5 is thinking major). The rest of the discussion at the tables is around substantive modifications and changes that, if made to the proposal, would lead the people at the table to support a judgment call. These items are recorded on a flip chart so that at the end of the session the output of each of the ten table groups can be shared with the CEO and the presenting team.

- CEO AND PRESENTING TEAM (60 minutes): The CEO and members of the team that just presented go off-line to a breakout room with the flip charts that include everyone’s numerical rating as well as the recommended modifications or changes. This meeting is an integration of ideas and input meetings and then a judgment preparation meeting for the CEO and the team. Schoonover and the team review all the input and can see what the ratings were for everyone, which means that he and the team can treat them differently. For example, if a fairly junior executive, new to the company, rated the expense savings recommendations a 5, Schoonover is not going to give it anywhere near the credence he would give a 5 from his chief financial officer. The numbers, however, are not the most important input to this meeting. It’s substantive recommendations that are. Schoonover used this meeting to coalesce his final position on the recommendations with a very participative set of input and discussion with the presenting team.

- PARALLEL MEETING WITH OTHER LEADERS (60 minutes): While the CEO is meeting with the presenting team, the rest of the CEO team is meeting with participants who fall in their chain of command to get their input on the recommendations. The head of marketing caucuses with his marketing participants, the head of retail with his, head of HR with his, and so on. They use this meeting to get ready for a final session—the judgment call session with the CEO.

- CEO AND TOP TEAM JUDGMENT CALL MEETING (45 minutes): The final step in the process is a judgment call session with the CEO and top team in what is called a “fishbowl.” The eighty participants get to see the meeting. They sit in chairs around the CEO and the top team so that there is total transparency in the judgment process. At this point the CEO has all the input from everyone, gets any additional input from his team, and then brings the meeting to a close with a summary of the judgment calls they are making and why.

EXECUTION PHASE

At the end of the multiday workshop Schoonover and his team had made judgment calls on each of the eleven projects. Because of the crisis that they were in, execution was launched immediately.

MAKE IT HAPPEN

Schoonover and the top team selected individuals from among the eighty to take ownership of the judgment calls and gave them milestones, timetables, and resources of both people and money to deliver the results.

LEARN AND ADJUST

The remainder of 2007 is a turnaround year for Circuit City. The eleven “Acceleration Initiative” projects are a key element in accelerating the transformation and are monitored on a weekly basis by Schoonover and the top team so that they are in a position to take ownership over any “redo loops.”

Schoonover’s Commitment to Leadership Development

Even though the process was to deal with a crisis, Schoonover made certain that it was an opportunity for all eighty team members to grow as leaders. In the final workshop where the teams went through the process described above, they also went through two very rigorous leadership feedback processes designed to keep making them better leaders.

One feedback process was done within the teams. Each individual on the team was asked to give “tough love” feedback to every other team member. The process had each participant provide written feedback to every other team member in three areas: (1) Your biggest contribution and strength on this team was…(2) What you need to work on to continue to grow as a leader…and (3) Future help I can provide to you in your leadership development journey is…

The written feedback was all posted on a flip chart for each person. Then the team focused on one member at a time. Everyone could read everyone else’s feedback and the focus on one person at a time was to make sure there was understanding, discussion, and help in translating the feedback into improvement action plans for every team member. The process was highly engaging, created new learning, and led each participant to have a clear action plan for continued improvement.

In addition to feedback within the teams, the top team reviewed all eighty participants on a nine-cell matrix: one axis indicated performance on the project—low, medium, and high; the other axis depicted the Circuit City values on the team—low, medium, and high. Each of the team coaches/sponsors (a member of Schoonover’s team) came to a top team meeting with all of the team members plotted on the nine-cell matrix and a written, qualitative rationale for where they appeared on the matrix.

Schoonover and his top team spent half a day reviewing all the team members and coming up with specific feedback that would be given to each of them to make them better leaders. This data also went into the formal succession planning process as an important data point.

The simultaneous crisis judgment process and leadership development process requires substantial time and discipline, as evidenced by Schoonover’s CEO calendar. The leaders who do this get the triple hit we discussed at the start of the chapter: (1) deal with the crisis; (2) engage the larger social network in the crisis judgment; and (3) develop leadership capacity.

THE RETURN ON INVESTMENT FOR ACCELERATION INITIATIVES

The process was designed to have immediate and long-term business impact. The business outcomes included the teams coming up with $300 million in new incremental revenue for the year and $20 million in profit; they also took out $150 million of SGA in 2007 and proposed another $200 million for 2008. They also completed and started executing plans for a new concept store. These are smaller, more efficient stores with new value propositions called “New City.” The Acceleration Initiative New Concept team developed the new physical architecture and the new format in the stores, as well as the all important human resource strategy, which included a totally new way of hiring, developing, and training the staff. The store associates all do the interviewing, selecting, and developing. The first of these stores was launched in the summer of 2007 and was dramatically outperforming other stores. The plan is to add hundreds of New City stores in the next two years.

This chapter provided two best-practice examples of leaders making crisis judgments. The Yum! Brands/Novak examples were food safety examples. In that industry Yum! has more risk exposure than any other fast-food chain because of the diversity of the ingredients, even compared to the larger McDonald’s. Every crisis that Novak has faced has led to good judgments. They have also given him the platform to keep developing other leaders who will be better and better at handling inevitable and unforeseen crises. The lesson for others is to clearly have mechanisms in place that provide quick responses to crises and that develop the next generation of leaders.

Schoonover at Circuit City is dealing with the legacy of a company that was underled and underinvested in prior to his arrival in the spring of 2006. He was previously at Best Buy, where he led much of the transformation efforts to customer centricity. Therefore, he understands only too well what the major competitor is capable of doing. He was quick in developing a Teachable Point of View and storyline for Circuit City, providing the platform for making good judgments. He missed the rapid change in the environment, but moved fast to develop his crisis judgment platform. The not-so-good lesson here is vigilance with regard to the external competitive environment, the same mistake made by Michael Dell. The good lesson is to engage the hearts and minds of the leadership and associates in supporting the judgments, engage them, and build future capacity for the organization.