11

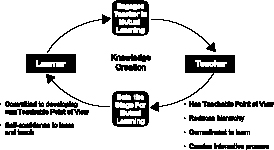

KNOWLEDGE CREATION

Leaders with Good Judgment Are Committed Learners

Leaders with Good Judgment Are Committed Learners

- They constantly evaluate their own performance.

- They seek knowledge and build on experience.

Knowledge Creation for All Constituencies Is an Explicitly Stated Goal

Knowledge Creation for All Constituencies Is an Explicitly Stated Goal

- Operating mechanisms support teaching and learning.

- Judgment capacity is a key leadership development target.

Customers, Stakeholders, the Larger Community Are Tapped for Input

Customers, Stakeholders, the Larger Community Are Tapped for Input

- Everyone teaches. Everyone learns.

- Frontline employees are the new knowledge workers.

I want to know everything I can about leadership. Because I don’t believe leaders are born. I don’t believe you spring fully armored out of the head of Athena to slay Hector in battle. I believe leaders choose to lead at some point in their life. And it’s because they have a call to action. They have a calling. They have something they want to make happen. They choose to be part of a change that they want to see in the world going around them, and they choose to step forward, and they choose to take the risk of leadership…the key is to be yourself. Be who you are. Be passionate about who you are and what you care about, and have fun.

—A. G. Lafley, P&G CEO1

We have a very strong belief that the first imperative to being a good leader who makes good judgments is a commitment to be a learner, to keep building one’s knowledge and wisdom. Leaders have two imperatives when it comes to knowledge creation. First and foremost, they must continuously strive to make themselves smarter and better at judgments by the kind of self journey to improvement that Immelt, Lafley, and other leaders profiled in this book have taken. In addition, leaders need to garner the support of their teams, their organizations, and their stakeholders in people, strategy, and crisis judgment making. While striving to make themselves better with the support of others, they must simultaneously invest in the development of leadership judgment in others: namely, their team, their organization, and the organization’s key stakeholder’s. This duality, making yourself better while teaching and developing others judgment capacity, is the key to good leadership.

SELF-KNOWLEDGE CREATION: A JOURNEY INTO YOURSELF

Good leaders are on a transformational journey starting with themselves, which carries over to their teams and organizations. To do this, leaders need the paradoxical combination of self-confidence and humility to learn. Twenty years of observing Jack Welch as GE’s leader provided deep insight into how a leader can create judgment self-knowledge.

First, it has to be a central agenda item of the leader. It takes commitment to self-learning, significant time, and relentless willingness to “look in the mirror” and a paradoxical self-confidence and humility. These are not descriptors that some would give to a leader like Jack Welch, often seen as just a leader of action. However, we have observed them firsthand. His quest for self-knowledge was fascinating to observe. It came in many forms. He relentlessly benchmarked other leaders, looking for new ideas from anywhere. He would use his almost every other week visits to Crotonville, not as a platform to pontificate but as a setting to learn about how his leadership was doing, collect new insights, and figure out ways of improving the company and his team so they could make better leadership judgments.

When Noel was running Crotonville in the 1980s, it was fascinating to observe Welch in action. He would often arrive toward the end of the day, taking the fifteen-minute helicopter ride from GE headquarters in Fairfield to Crotonville, GE’s leadership development institute, and walk into the “Pit” the 110-person tiered classroom where all those in programs at Crotonville would come to spend a few hours with the CEO. There might be first-time managers, twenty-eight-year-old engineers, executive program participants, twenty-year GE veterans who were pretty far up the hierarchy, all in the same session.

Welch would share ten or fifteen minutes maximum of what was on his mind, ranging from world events that might be impacting GE, to his Teachable Point of View on leadership, to challenges in some of the businesses, like the difficulty of integrating Yokogawa Medical Systems in 1987 with the Wisconsin headquarters. He would then tell the group, “I am here to discuss anything that is on your mind, from globalization to GE values, to why we made a particular acquisition.” These were not straight question-and-answer sessions. They were often question and question and highly interactive conversations with Welch, who wanted to know how people in the group thought. He actively solicited their opinions, asked how they would solve a problem, probe at why bosses hadn’t answered some question about the business. It was always a very interactive give-and-take mutual learning session, creating what we have called a virtuous teaching cycle: the teacher (Welch) shares his Teachable Point of View but then creates an environment where the learners become his teachers.

Virtuous Teaching Cycles

Welch engaged in two other activities to get him smarter. Before the 110 leaders broke for an informal cocktail session with Welch, each of the 110 filled out a feedback form that asked three questions: (1) As a result of this session, what has been resolved for me? (2) As a result of this session what is still unresolved or still troubles me? and (3) What is my biggest takeaway from the session? Welch would have these handwritten sheets either before he left in the helicopter or within twenty-four hours. He read them as the candor and insights kept him learning. People were overwhelmingly candid and most signed the forms and indicated where they were from in GE so Welch got regular feedback, which might include: What was resolved—“Now I understand why we sold the aerospace business.” I am still troubled by “why we are still not settling the PCB controversy in the Hudson River when we are saying we want to be good environmentalists.” The major takeaway might be “I learned things about my business that our leader should have taken the time to explain, and I am going to challenge him.”

Welch would then use the cocktail time to work the crowd as another source of learning, getting into often heated conversations with three or four managers at a time. One time he was standing with five or six managers from his old business, Plastics, challenging them with why they messed up with a major customer.

The regular teaching and learning interaction described above is in addition to the action learning platforms that were created at Crotonville when Noel was heading it up in the late 1980s and continue today. Basically, the GE CEO uses the executive programs to have teams work on real issues for GE, ranging from having teams go to South Korea for a couple of weeks to reexamine the GE strategy in that region, to coming up with strategy ideas with Immelt for how GE needs to handle global citizenship issues, both environmental and human service (these are multiweek action learning task forces).

Welch chose Jeff Immelt to succeed him as CEO in large part because he recognized that Immelt was a leader with an insatiable thirst for being better, who invested himself in self-knowledge creation. Immelt told an incoming class of MBAs at the University of Michigan:

The first part of leadership is an intense journey into yourself. It’s a commitment and an intense journey into your soul. How fast can you change? How willing are you to take feedback? Do you believe in self-renewal? Do you believe in self-reflection? Are you willing to take those journeys to explore how you can become better and do it every day? How much can you learn? Can you look in the mirror every day and say, gee, I wish I had done that differently, boy I think I’ve got to do better here…you’ve got to be willing to do an intense journey into yourself…. I’ve been lucky, you know, because I’ve got to do things that I love with people that I love. But more than anything else, the burning desire inside me was to get the best out of what I could be and go on that journey.2

Immelt also uses the Crotonville platform for “dreaming sessions” with customers and suppliers to develop new CEO knowledge.

A. G. Lafley, Jeff Immelt, Jim Owen, David Novak, and Steve Bennett all use their leadership development platforms as knowledge creation processes as well. They all have extensive commitments to working real problems with their leaders, engaging in virtuous teaching cycles so that they and their organizations create knowledge collaboratively. This is counter to what the vast majority of companies do—outsourcing leadership development to business schools and consultants, reading case studies and not having the leaders of the company teaching and driving real action learning projects. The traditional management development both in companies and at business schools delivers a fraction of the return on the investment of those that fully engage in knowledge creation; this is the opposite of academic knowledge download (rather than a mutual learning approach).

Self-Knowledge Creation Requires Reflection as Well as Action

Action with no reflection does not create knowledge. Our bad judgment leaders often end up destroying knowledge through hip-shooting and acting out the same behaviors that got them to succeed in the past even as the world around them has changed.

A. G. Lafley makes it clear that to have good leadership judgment you have to

first, know yourself…. You need to be in touch with what your aspirations really are; what your dreams really are. You need to understand your value system. You know, what is really meaningful to you? What do you really care about? What counts in your life?3

Knowledge creation for good judgment requires the leader to have a discipline to reflect and write. We have observed that leaders who get better and better at their judgments work at it not just in real-time interactive sessions, but then develop their Teachable Point of View as a work in progress. They also tend to write as a reflective tool, whether it is the twenty annual report letters Welch personally wrote, a tradition Immelt has followed at GE, or the curriculum that David Novak personally created for teaching his Yum! Brand leaders. Reflection, articulation, and then continuous improvement are the hallmarks of a leader continuously developing better judgment. This also includes a tough look at failures for learning.

Jeff Immelt describes how he works on improving his leadership judgment; it takes time and discipline to “wallow in ideas,” as he describes it, before making a final judgment call.

You get these things by wallowing in them awhile. We had a few steps worked out in 2003, but it took another two years to finish the process. Jack was a great teacher in this regard. I would see him wallow in something like Six Sigma, where easily the first two years were tough. People would say, “Whoa, what the hell is this?” Still, he wouldn’t move on to something else. He’d get the different businesses sharing ideas, and everything always crystallized in the end. He was a good initiative driver.4

The “wallowing” learning must ultimately get reflected in the leader continuously examining and improving his/her Teachable Point of View.

Self-Knowledge Creation and the Judgment Process

Developing judgment leadership capacity occurs during all phases of the process. A. G. Lafley has a well articulated Teachable Point of View that he uses not only to guide his own development but to develop judgment in his leaders at P&G. Immelt and the other good judgment leaders we have studied all share this common trait. It starts with facing reality, as Lafley states:

the ability to see things as they are, not as I would like them to be…to see things as they are, to come to grips with reality, not to see the world through rose-colored glasses. One of the things that helped me is, I’m reasonably good at seeing things and accepting them as they are, and then dealing with them.5

The leader needs to be real clear about what it means to make judgment calls. Lafley reflects on his point of view and underscores the importance of action.

Strategy, in my world, is critical, because strategy is the choice set. It’s the set of choices that we make that guide the allocation of the human resource, and the allocation of the financial resource, and frankly, place bets on what we’re going to do, and more importantly, what we’re not going to do.6

Lafley is on a continuous learning and knowledge creation journey. He is very clear that being able to make the tough judgment calls is critical to being a good leader; he shared what goes on in his mind when it comes to making judgment calls on strategy:

But we chose to grow from our core—core businesses, core capabilities and core technologies that we know. We chose to create a portfolio for the first half of the twenty-first century that would grow faster, and hence, our move into beauty care, health care and personal care. We chose to commit to low-income consumers in developing markets, ’cause we knew the growth was going to be faster there. Demographics drive our business.

We chose to focus on our core strengths and get better, in fact, best in class. So we want to be the best at understanding consumers, the best at creating brands and building brands, the best at innovating consumer products, the best at going to market through our channels of distribution and retailers, and the best at leveraging global scale. And then we wanted to be more productive than any other consumer products company in the world, and we wanted to attract the strongest talent and build the strongest cadre of leadership.7

It is obvious by now that our point of view on good judgment means the leader totally owns execution. If it does not happen and if the leader does not continuously monitor and learn and adjust, good judgments turn into bad judgments. Again, A. G. Lafley has a very clear point of view:

The power of execution. And execution is what really happens, what you really do. And execution, in fact, is the only strategy that your consumer…it’s the only strategy our retailer…it’s the only strategy our competitor…it’s the only strategy anybody else on the outside ever sees. They don’t see the strategy we wrote down. They don’t see the choice set.8

The leader’s knowledge creation journey is the necessary condition for then focusing on knowledge creation at the social network, organizational, and contextual levels where the leader not only mobilizes these domains to support the judgment process but builds their capacity to develop judgment knowledge capacity.

SOCIAL NETWORK/TEAM KNOWLEDGE CREATION

It is up to the leader to build knowledge creation processes for his/ her team and to ensure that they get executed. Bill George, former Medtronic CEO, reflects on this critical element of judgment capacity building at the team and social network level:

Every job I had been in in my life, including all my jobs at Medtronic, I never knew a fraction about the business as much as my team did at Litton. So what I did was just learn how to form a team around the people that I could rely on intimately, close. And I developed very professionally intimate relationships with my subordinates. I’ve always believed in separating my friendships in my personal life from my business life. So I don’t want all my friends to be the people I work with because I need to get away and I want to have different types of friends. But I developed very intimate, professional relationships so we could talk openly about anything.

Virtually every leader relies on a group of trusted advisers. Throughout history, whether Kennedy’s kitchen cabinet or Nicholas II’s Rasputin, these individuals or groups have influenced key leadership judgments; some good, some bad. For most leaders, their team is the group with which they spend the most time. When there are difficult judgments to be made, they convene their team to debate and deliberate. Making choices about who we surround ourselves with and from whom we take counsel is perhaps the biggest judgment that any leader can make. Building a social network that keeps developing knowledge creation capacity is central to the success of a leader.

Who Is on Your Team

The first component of this is making a conscious judgment about each individual on your team. You must ask the question: Does this person help the team to make better judgments? Organizations are littered with technically competent people who possess poor judgment. Rather than contribute to the judgment process, they encumber their teams with false assumptions, opaque judgment processes, or indecision. There should be no “neutral” ratings in your assessments. Saying that someone is neutral is equivalent to that person’s failing to impact the judgment process. There is a tremendous opportunity cost to having someone who is not trusted or incapable of offering good advice as you make judgment calls.

Assuming a team and social network that has a solid level of trust, it is then important to look at what each person brings to the team. Again, this is not a question of whether or not they are capable of doing their job; rather, it is whether they personally exercise good judgment and have a positive impact on the team’s judgment process.

If a team has been well formulated, there are diverse skills, perspectives, and relationships that can help the leader as he or she prepares to make a judgment call. Some of the assets that team members bring may include:

- Domain expertise: Deep understanding of a technical area such as a functional specialty or technology.

- Industry knowledge: The ability to diagnose industry trends or help place changes in historical context that is predictive of possible future outcomes.

- Organizational knowledge: Understanding of the organization’s competencies, talent, networks, processes, and culture that suggests execution capability or receptivity to change.

- Constituent knowledge: Up-to-date information and relationships about one or more key constituents such as regulatory agencies, key customers, or suppliers that predict how these actors will respond to your organization’s moves.

- Access to information: Personal networks, relationships, and know-how that enable the person to get reliable answers to questions even if they do not have the answers themselves.

- External experience: A different perspective based on experiences outside the company or industry that helps to identify best practices or alternate approaches.

- Unconventional problem solving: A differentiated thought style that can generate creative solutions not likely to come from standard analyses or the industry’s conventional wisdom.

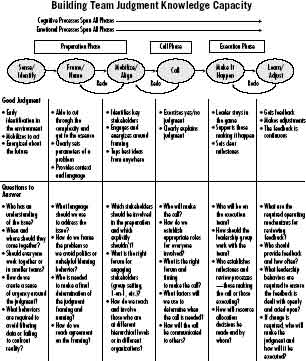

Team Dynamics for Good Judgment

Throughout the book we have portrayed judgment as a dynamic, emotional process that must account for the human actors who are involved. As a leader, you establish a social architecture—how people interact and the energy generated by those interactions—that directly influences the quality of the judgment process.

At each stage (preparation, call, execution), you must manage the process for your team. The framework on the next page provides the leader with guidelines and diagnostic questions to build team judgment capacity.

ORGANIZATION KNOWLEDGE CREATION

Building judgment capacity at scale in a global organization the size and complexity of GE, Yum! Brands, Wal-Mart, or Toyota requires the leader to be a large-scale social architect. It means creating processes that engage thousands of leaders in judgment muscle strengthening activities.

In chapter 10, we saw how Schoonover at Circuit City created an organization level knowledge creation process at scale during a crisis. The challenge for Schoonover will be to create steady-state, noncrisis, ongoing knowledge creation processes for thousands of his associates, which he undertook with a new operating system of how they do strategy, budgeting, and succession planning.

Leaders have three major levers for large-scale knowledge creation. First, there are the operating systems of the organization, including strategy formulation, budget processes, and succession planning. Second, there are the leadership development activities spread over one’s career, job experiences, rotations, and formal development experiences at different career stages. Third, there are the large-scale, total company knowledge creation platforms, such as training the whole workforce in Six Sigma quality, or cascade teaching to everyone in the company.

Knowledge Creation Through Operating Systems

Immelt inherited from Welch a totally revamped operating system of GE, one that was transformed into a learning and judgment creation set of mechanisms carried out throughout the year. The GE model has become the benchmark for many other companies including Best Buy, Intuit, 3M, Boeing, Yum! Brands, and Honeywell, to name a few. The true essence of what Welch accomplished was a radical transformation of what was purely a set of traditional bureaucratic processes into a learning/teaching judgment building set of activities.

“The GE Operating System” that follows is the actual diagram used to teach Welch’s organization about the operating system. The written portion in the right margin is in his own words and underscores the learning system aspect of the processes.

Immelt inherited the operating system and made significant additions, including a “session T,” which is a technology process for knowledge creation. The heads of businesses and key team members go to the Global Research Center four times a year to immerse themselves in interaction with the researchers to stimulate growth from new technology platforms.

As was discussed in chapter 8, “Strategy Judgments at GE,” GE leaders are generating new knowledge regarding technology growth platforms that set the stage for new strategic judgment while simultaneously building the organization’s judgment capacity.

These knowledge creation operating systems are always a work in progress and require the leader to keep redesigning them as interactive virtuous teaching cycles, or else organizational inertia and dry rot will set in to turn them back into bureaucratic knowledge blockers and destroyers.

Developing Leadership Judgment

All leadership development, from new hires through senior leaders, needs to be geared toward knowledge creation for better leadership judgments, both to support real-time judgments and to develop the next generation’s capacity for leadership judgment.

The GE Operating System

One platform for this was described in chapter 7, “Strategy Judgments,” at Best Buy. The shift to customer centricity was developed off an action learning platform, six teams coming up with the new segments for Best Buy to focus on. Over the six-month action learning process each of the leaders not only worked on solving the strategic segment challenge but received personal leadership feedback and development around business acumen, leading change, and team dynamics, all aimed at growing their judgment capacity. At the end of the process every leader was assessed by the CEO, Anderson, and the top team on their judgment performance and their leadership behaviors in the action learning process, which consumed about 30 percent of their time over the six months while they continued to have to manage their regular job. The action learning process not only framed and created the segments, but provided the development and selection platform for the leaders of these new segments. The leaders were selected for both their demonstrated leadership judgment in the process and their future potential to lead the building of the segments and thus their people, strategy, and crisis judgment as it would apply to their new segment.

This same action learning platform was used at GE Medical Systems in the early 1990s as it globalized and integrated two acquisitions, Yokogawa Medical Systems (two thousand Japanese) and Thomson-CGR (six thousand Frenchmen), with GE’s twelve thousand Wisconsin-based makers of CAT scanners, MRIs, and X-ray equipment, and at Royal Bank of Canada to drive their shift to customer centricity, and at Royal Dutch Shell, Intuit, and Intel.

JUDGMENT CAPACITY BUILDING AT THE FRONT LINE

When Peter Drucker presciently introduced the world to the concept of knowledge workers, he urged managers to treat knowledge workers as assets rather than as costs. Drucker’s line of thinking has been popularized to the point at which it can be found in an enormous volume of corporate reports and management writing. Drucker asked a fundamental question that, despite the increased attention, organizations still struggle with: What is needed to increase (knowledge workers’) productivity and to convert their increased productivity into performance capacity for the organization?

In their bid to create a differentiated customer experience, Best Buy and Intuit are realizing that the key to answering Drucker’s question lies in enabling knowledge workers at the front lines to make good judgment calls. The process starts with the CEO and senior leaders setting clear direction for the organization and defining the role and scope of contribution expected of frontline leaders. The senior leadership is ultimately responsible for setting the strategy, reinforcing desired values, energizing the organization, and making tough calls on resource allocation and staffing. In short, the senior leaders are responsible for developing a Teachable Point of View, which is taught throughout their organizations. Our work at both Intuit and Best Buy started with helping the senior teams develop such a Teachable Point of View.

Trilogy Software, an Austin, Texas, company founded by Stanford dropout Joe Liemandt, is a prototypical company for the knowledge economy. Selling complex enterprise software, Trilogy is an extremely successful private enterprise that partners with many Fortune 50 companies. Since its founding, it has relied on hiring the best and brightest computer scientists from top campuses. In a Harvard Business Review article, we chronicled how Joe Liemandt created Trilogy University, a three-month orientation “boot camp,” to simultaneously indoctrinate these hotshot new hires while creating the next generation of products. Today, Trilogy runs its university in Bangalore, India, because the bulk of its hiring is at the top Indian and Chinese universities, and new recruits create products for a global market.

Trilogy’s workers fit the old stereotype of the knowledge worker—the highly trained engineering and computer science graduate. The importance of knowledge workers such as these cannot be disputed, but we see the emergence of a new breed of knowledge workers.

Intuit, the Mountain View, California, company, also produces software. Its TurboTax, Quicken, QuickBooks, and other software solutions serve both small enterprises and individual consumers. As with Trilogy, computer scientists play a vital role in developing its products. Unlike Trilogy, however, Intuit relies heavily on specialists to support accountants and retail customers. These knowledge workers don’t necessarily hail from top universities or write complex computer code. They are frontline leaders and agents working in call centers, often paid an hourly rate. Intuit has learned that these call service agents can have a critical impact on customers and sales by both identifying customer needs and solving after-sale problems.

At Intuit, frontline leaders take responsibility for sharing best practices and creating new knowledge about customer needs. For example, one frontline manager developed a process in which customer service agents now meet several times a week to discuss common customer problems and role-play responses. By doing so, they not only share knowledge but also creatively come up with newer and more innovative ideas to enhance the customer experience. As a result, there has been a nearly 40 percent increase in the measure of customer satisfaction.

Intuit demonstrates how knowledge creation increasingly is shifting to the customer interface. Best Buy is another example. A frontline associate in one of Best Buy’s California stores knew that the area surrounding his store had a large number of real estate agents. After several failures to sell digital cameras to real estate agents, the associate researched their needs. Having been trained to diagnose customer problems and empowered to create his own solutions, he realized that real estate agents needed to take pictures and then e-mail or print them on the spot, often from their cars. He assembled a bundle of products and software that would enable an agent to snap a digital photo, produce the photo with a mobile printer that fit easily in any backseat, or e-mail the picture from a laptop or PDA. After the product bundle became a hot seller in the area, one of the agents invited the Best Buy associate to present to the real estate agents at a monthly meeting at the local Chamber of Commerce. The associate’s innovation resulted in thousands of dollars of incremental sales and a group of new customers who continued to shop at Best Buy.

The stories at Best Buy and Intuit demonstrate the impact that frontline associates have when they exercise good judgment and come up with innovative solutions to customer opportunities. We have collaborated with these companies in developing frontline leadership capacity for customer-centric knowledge creation. The specific solutions these frontline leaders provided their customers could not be anticipated in advance. Instead, leaders had to be adaptive, weigh their options, and figure out how to please their customers.

As companies strive to differentiate themselves with inundated consumers, more and more are realizing that knowledge is created at the customer interface, not at headquarters or in isolated development groups. This requires the full engagement and intellect of frontline associates. It can only happen with top-down support, a clearly articulated strategy with strong enablers at all levels of the organization, and intensive training and development of frontline leaders and their associates.

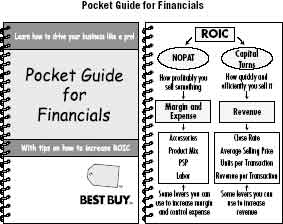

Stories like this are not uncommon at Best Buy. They could not have happened, however, if the company had not invested in the judgment capability of its frontline leaders. These leaders were able to read their store profit-and-loss statements, calculate return on invested capital, and understand their net operating profit targets. In contrast to the company’s traditional policy of handing down only operating targets without explanation, business acumen gave frontline leaders a new capability on which to base their judgment calls. The material in “Pocket Guide for Financials” is an example of frontline knowledge creation. A team of hourly associates in one of the stores developed teaching materials to teach their colleagues about customer centricity. They worked on their own time to create a booklet that was originally called “Customer Centricity for Dummies” until the store manager very supportively explained to them that they were violating both trademark and copyright laws. They quickly learned and changed the cover. The booklet walks through examples, such as creating a “T-shirt” stand, how to get capital, how to measure capital turns, and how to calculate return on invested capital. They then go from case example to application in their Best Buy store. The point is to unleash the knowledge-creating capability in people, and it is amazing how smart they can become and make others around them as well.

Best Buy also had to build new operating mechanisms to support knowledge creation in the stores. This included a morning forty-five-minute “chalk talk” with twenty to thirty associates before the store opened. They reviewed daily P&Ls, close rates, what happened with their segment the day before, and ideas for improving the performance for this day. The sessions were highly interactive, with the store manager and team fully engaged with the hourly associates. They were all generating new knowledge.

At Best Buy, there are now hundreds of stories describing how frontline employees dynamically created customer solutions. Innovative approaches to problems as diverse as ethnic marketing programs, tailored product displays, and new product introductions have been identified and implemented directly by frontline associates. This could only happen because Brad Anderson, Best Buy’s CEO, defined the organization’s strategy around “customer centricity,” a concept that we helped Best Buy’s leadership team frame in partnership with Larry Selden from Columbia University.

In Brad’s judgment, the strategy that had made Best Buy the leading consumer electronics seller in North America and a top-performing stock would not sustain the company’s success. Anderson had to create the conditions for enabling frontline leaders to fully implement a customer-centered strategy. The Best Buy transformation is still a work in progress as it has required a massive revolution. The company historically was built on strong centralization, with employees at its Minnesota headquarters setting strategy and passing down “knowledge” and direction for the troops to follow. Today, the “troops” are expected to act as local field generals, generating solutions and new knowledge. Best Buy continues to invert the organizational pyramid, empowering employees to turn customer hypotheses into business cases that can then guide headquarters to provide support for what was traditionally process controlled.

The transformation at Best Buy has required massive change of information, skills, and tools to make good judgments. The company is also providing each store with a local profit-and-loss statement, good customer data, and performance management tools. Similarly, the career paths, compensation systems, merchandising programs, and numerous other facets of the business have had to be entirely rethought.

Intuit’s Knowledge Creation in Call Centers

At Intuit the focus is on simplifying the technical challenges call center agents face in trying to find information, execute company processes, and share knowledge with one another. Intuit has engaged frontline associates directly in identifying and changing how the company works to support better customer interactions. Intuit is reducing the bureaucracy that stands in the way of letting customer agents focus on customers and make good judgments.

As a result of CEO Steve Bennett’s driven effort, the call center managers now create virtuous teaching cycles with their associates when examining the success metrics their teams use. One example was a manager who worked with her team to identify the vital metrics to measure team effectiveness and now assembles the team weekly to diagnose progress and share practices for improving each agent’s customer impact.

Teaching Frontline Managers to Teach

Best Buy, Intuit, and Trilogy all make the enormous investment of teaching frontline managers how to coach and teach their associates. At Best Buy, thousands of employees have participated in workshops teaching everything from financial basics to customer segmentation approaches to frontline leadership.

Intuit has required its call center managers to become teachers. We launched the process with a rigorous three-day process designed to prepare frontline managers to be more effective teachers of frontline agents. Following the workshop, each frontline manager conducted his or her own disciplined, highly interactive workshop for groups of frontline leaders. No consultants or staff personnel were allowed to teach. At the end of the three days the frontline leaders had new concepts and tools for enhancing the effectiveness of their call center agents. The frontline leaders identified how they could better structure their work to deliver the business strategy, how they could eliminate unnecessary activities, and how they could reshape goal setting and performance management. The frontline leaders also engaged the agents to provide input on companywide initiatives to streamline operational processes. As knowledge creation increasingly moves to the front lines, Intuit recognizes that its managers must be more skilled than ever in leadership fundamentals.

Intuit’s Frontline Leader Process

Intuit’s investment in developing the judgment capability of frontline leaders requires them to attend two workshop sessions, teach their own teams, implement new work routines, and execute a knowledge-creation project. The “Intuit Frontline Program” provides an overview of the Intuit process for the front line.

Intuit Frontline Program

Step 1:Three-Day Workshop

- Frontline leaders are immersed in the strategy, values, and vision and taught how to translate them to their area.

- Frontline leaders are immersed in business acumen.

- Frontline leaders are taught to focus on creating a team-teachable point of view and using operating mechanisms as virtuous teaching cycles.

- Frontline leaders are taught how different employee styles and capabilities may be deployed.

- Frontline leaders are prepared to teach.

Step 2:Frontline Leaders Teach

- Frontline leaders who attended the three-day workshop are required to teach—they personally re-create the workshop they attended, doing all of the teaching themselves.

- The process develops their ongoing teaching and coaching capability.

Step 3:Knowledge-Creation Project

- Frontline leaders work with their team of frontline associates to share knowledge and implement a project with measurable business impact.

Step 4:Two-Day Follow-Up Workshop

- Frontline leaders share results and best practices with one another.

- Frontline leaders continue learning on business acumen, company support processes, frontline leadership, and performance management.

When most people picture knowledge workers, they think of engineers, scientists, or service professionals, not hourly sales people or call center agents. However, as numerous companies increasingly attempt to differentiate themselves through their service, they are recognizing that the best strategy is creating judgment capability at the front lines.

The paradox of shifting power to the front lines is that it requires senior leaders to use their authority to overcome the technical, political, and cultural barriers that often stand in the way. Companies must actively invest in creating the support systems that enable frontline leaders to make good judgment calls. When they do, they realize that frontline leaders are those most skilled in making local decisions to simultaneously delight customers and protect the bottom line and continuously create knowledge.

CONTEXTUAL KNOWLEDGE CREATION

The final knowledge creation arena is how to work with key stakeholders, the board, the suppliers, the customers, and the communities in which the organization operates.

Immelt personally hosts customer dreaming sessions at Crotonville with his team and teams from key customer groups. Immelt describes a session as follows:

We hosted what we call a dreaming session in the summer of 2004 with the 30 biggest utilities. Some of the top players in the industry—CEOs like Jim Roberts and David Rutledge—came to Crotonville and heard Jeff Sachs from Columbia talk about global warming. There were other speakers who were pretty compelling on different topics, and breakout sessions. I floated the idea of doing something on public policy on greenhouse gases, and we had a good debate.9

This interactive virtuous teaching cycle process helped Immelt frame and name “ecomagination” as a way “to show the organization that it’s OK to stick your neck out and even to make customers a bit uncomfortable.” Leaders need to develop customer and supplier interactive processes for developing new knowledge.

Board Knowledge Creation

In the defensive post–Sarbanes Oxley age of boards of directors, all too many publicly traded companies are not partnered with their boards as knowledge creators. The paranoia and procedures imposed on boards due to the fallout from the Enron, Tyco, ImClone, WorldCom, and other ethical meltdowns is undermining the very real potential for boards to partner in knowledge creation.

Best Buy Board Engagement in Customer Centricity

Early on in the launch of customer centricity at Best Buy, the board was present and engaged with the 164 officers in the first big multiday workshop. Board members sat in with the teams and worked side by side with the leaders on what this meant for Best Buy. The preparation for leaders to teach thousands of Best Buy leaders was with the board members working with the executives. For half a day of the workshop, board members were mixed into groups of five or six Best Buy leaders, helping them work on their Teachable Points of View to take back to their teams.

During the transformation and action learning process to come up with the Best Buy segments and to move the organization forward to a new strategic platform, the board was engaged every step of the way. Larry Selden and Noel worked with the board and teams in three different sessions. These sessions involved having members of the action learning teams work interactively with the board on ideas they were developing for different segments, the value propositions. The board also spent time in the stores, walking them and interacting with the associates who were driving the transformation at the customer interface. Boards can and should be partnered in knowledge creation.

Community Engagement: Global Citizenship

The final contextual dimension is the wider societal community in which the organization operates. Over the past decade Noel has worked with Best Buy, Circuit City, Ameritech, U.S. West, Intuit, Genentech, HarperCollins, Ford, Royal/Dutch Shell, Royal Bank of Scotland, and Covad to incorporate corporate citizenship, dealing with both environmental and human capital challenges and blending them into the mainstream of leadership development. The leaders of the company are required to have a Teachable Point of View on “citizenship” and to engage their own teams in community work as a way to develop them, give back to the community, and also generate new knowledge.

At Best Buy, for example, all the leadership development programs would as a group spend half a day in the downtown Minneapolis Boys and Girls Club working one on one with the children. At Genentech, hundreds of leaders, as a regular part of the leadership development programs, work with Opportunities Industrialization Center West, a job retraining program in East Palo Alto.

GE’s Global Citizenship efforts have truly become large scale and mainstream to being a leader in the company. There are large-scale partnerships in Ghana to develop a community with both GE products and volunteers. In Stamford, Connecticut, there is a partnership to work with the school system that also exists in Louisville and Cincinnati.

The point of these efforts is that with the right leadership, the CEO drives their workforce to be a part of what Immelt has challenged his organization to be: namely, a company—that gives back globally to the communities in which the company operates.