Chapter 2

How Sleep Works

We live in Colorado, a state with world-class skiing. We use the collective knowledge base about skiing to teach people about sleep. It sounds off-topic, but learning to ski—and specifically learning to ski off-trail and in the trees—can teach you a lot about sleep. When people are learning to ski this type of terrain, there is a natural concern about hitting a tree or other obstacles. As a result, novice skiers typically focus on the trees to avoid a collision. The journey down the mountain can be slow and anxiety-ridden.

More experienced skiers know that, to be successful, you need to focus on the space in between the trees. Your line of vision determines where your body goes. Your attention needs to shift from what you fear in that moment to where you want to be. Interestingly, even after skiers are told it would be best to shift focus, they still tend to look at the trees. It feels counterintuitive to not be acutely attentive to these large objects that would cause much pain if you were to collide with them. It is only over time and with repetition that skiers train their brains to shift their focus to the space in between the trees, allowing the trees to become part of the background. Concentrating on these open spaces allows for more freedom to create a continuous motion down the hill because you are now leading your body on the path of where you want to go, rather than avoiding where you do not want to go. It requires a willingness to trust in a process that does not immediately make sense to your mind. When this paradigm shift occurs, there is an “aha” moment, followed by an increase in confidence, ability, and enjoyment.

Sleep shares this paradigm. It is natural for people who are not sleeping well to become hyperfocused on what is going wrong, and to see danger or vulnerability around every curve. Yet this very vigilance can make sleep even harder, just like staring at the trees makes it more likely that you will run into one. Learning how to improve your sleep involves shifting your focus from fixing or avoiding your immediate sleep problems (the trees), to promoting and optimizing your healthy sleep (the open spaces). Concentrating on the components of healthy sleep will allow you more freedom to create a workable relationship with sleep, and a willingness to trust the process. When people make this shift in focus regarding their sleep, we typically get that same “aha” moment that leads to increased confidence and success (and, yes, even enjoyment) with sleep.

In this chapter we will discuss the “open spaces,” or how sleep works when we are sleeping well. Remember: understanding what you are targeting (healthy sleep) will help you achieve it!

The Physiology of Sleep

Your sleep patterns are a result of a complex and impressive array of bodily and psychological processes. We do not review all of these moving parts in this book. Rather, we highlight what is most relevant for this sleep program. The two big players are your sleep drive and your internal body clock.

Your Sleep Drive

Your sleep drive (Borbely, 1982) is your body’s personal tracker of your sleep. It is a drive because sleep is essential to survival: your body has an innate drive to get sleep in order to live. It tracks the amount of time you are awake and the amount of time you are asleep. When you are awake, your sleep drive goes up; as you sleep, the pressure valve is opened and your sleep drive goes down. When your sleep drive is high, your body will provide you with cues that it is important to go to sleep.

Your Internal Body Clock

Your internal body clock helps you navigate the cycles of day and night. This body clock is also known as your circadian rhythm (Halberg, 1969) and is responsible for the timing of your sleep. It is located inside your brain. Your body clock influences sleepiness and wakefulness by its impact on the endocrine system, the nervous system, and the body’s core body temperature.

The endocrine system is responsible for hormones. The hormones that are most important for sleep include melatonin and cortisol. The nervous system is responsible for signaling to your brain how to respond to the environment, including when to react and when to relax. Your core body temperature is registered by your brain in tiny increments of tenths of a degree. Fluctuations significantly influence your energy and focus.

When everything is working well, day after day your body clock produces consistent fluctuations in cortisol and melatonin production, nervous system arousal, and core body temperature. You may experience this as predictable waves of energy and focus throughout the day. For example, you may notice feeling more alert and focused at midmorning and early evening, with a dip in energy in the late afternoon.

The body clock runs on a slightly longer cycle than our twenty-four-hour day. In fact, “circadian” literally translates to “about a day.” Remarkably, the human brain is capable of aligning these two clocks. This requires support from the environment. We know this from a famous experiment conducted in Europe in the mid-1960s (Wever, 1979). When people with healthy body clocks were put in a windowless basement for an extended period of time, their body clocks got confused. They no longer had a twenty-four-hour sleep-wake rhythm. It turns out that light exposure is a natural—and essential—regulator that keeps us on schedule. Nightfall is a trigger for us to sleep, and daybreak is a trigger for us to awaken.

There is variability in how robust the body clock is in handling environmental changes. Some people easily adjust to external clock changes, such as Daylight Savings Time or travel across time zones. People with robust clocks may feel fine with an irregular sleep or meal schedule. But others have greater difficulty adjusting to changes in the external clock, and may feel a lot more out of kilter when they do not have a regular routine.

A Well-Choreographed Dance

Understanding the interaction between the sleep drive and the body clock is essential to understanding how sleep works. It also is extraordinarily helpful in understanding your insomnia. The sleep drive and the internal body clock are two separate, independent biological processes, but they must work together in a complementary, synchronized fashion to support your wake and sleep patterns.

We can use the metaphor of meals and appetite to better understand this relationship. In many cultures the norm is to eat three meals a day, and the timing of these meals is typically in the morning, at midday, and in the evening. When your appetite is balanced, eating at the scheduled mealtime is something your body craves. It will provide you with cues, such as hunger pangs, at the time it expects food. However, if your appetite is out of sorts—perhaps because you ate a large meal or too many snacks—then eating at the scheduled mealtime will not be something your body craves. The more consistent you are with your mealtime schedule and the amount of food you eat at mealtime, the more balanced your appetites are. It is this synchronous process that allows you to know it is time to eat without looking at the clock. It also allows you to accurately predict how much food you need to prepare in order to be neither too hungry nor too full after your meal.

Your body clock and sleep drive work in a very similar manner to mealtime and appetite. In our culture the norm is to have a distinct wake cycle and a distinct sleep cycle. When your body clock and sleep drive are in sync, your body craves sleep at a consistent time. It will provide you with cues, such as sleepiness, at the time it expects sleep. If, for several months, you have kept a schedule of going to bed at 10 p.m. and rising at 6 a.m., your body will be primed to sleep during these hours. This is a synchronous process in that when you schedule the opportunity to sleep at roughly the same time each day, you have the necessary resources to do so. If your body clock or sleep drive are out of sorts—perhaps because you did not sleep well over the past few days or took a long nap earlier in the day—then sleeping at your regular time may become more challenging.

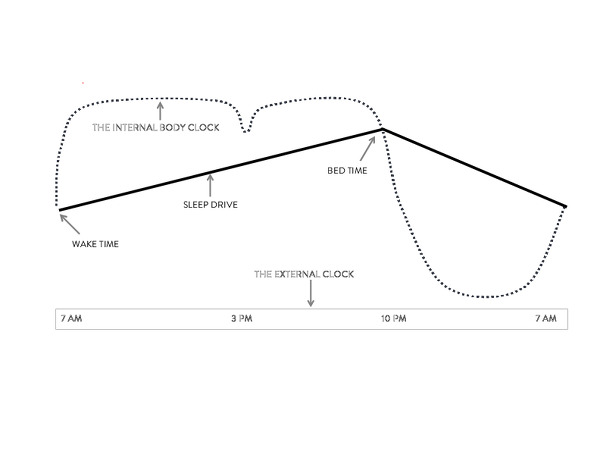

Figure 2.1 provides a visual depiction of the body clock and sleep drive, and how they interact with each other in a well-coordinated dance. This model is often called the “two-wave model,” highlighting the fact that both the body clock and the sleep drive fluctuate in wavelike fashion.

Notice the lines crossing at the wake times and bedtimes. These intersections indicate a change in which another wave is dominant. The change sets in motion the wake or sleep pattern. At wake time, the body clock’s signals for alertness are stronger than the drive for sleep, setting us up for the day. The body clock’s alerting force remains the stronger drive throughout the day, allowing us to stay awake and focused, even as our sleep drive pressure mounts. At bedtime, the sleep drive becomes stronger than the alerting force of the body clock, setting us up for sleep. As we sleep, the sleep drive decreases. However, it remains stronger than the alerting force until morning. This allows us not only to fall asleep, but to stay asleep throughout the sleep cycle.

As you will see in the next chapter, this model helps explain how you can be extremely tired, yet be unable to sleep. You are tired because your sleep drive is high. You are unable to sleep well because your body clock is not primed for sleep. Your sleep drive and body clock are out of sync.

How You Influence Your Sleep Physiology

We have already explained that the sleep drive is affected only by sleep: it gets stronger and stronger the longer you are awake, and steadily decreases as you sleep. We have also stated that there are individual differences in how robust our body clocks are, and how sensitive our body clocks are to the environmental cues of light and darkness. Maybe your mind has come to the conclusion that physiological aspects of sleep are “hardwired” and cannot be changed.

We have good news for you! Your behavior (what you do) and your thought processes (what, when, and where you think) also heavily influence your body clock and how it aligns with your sleep drive. Although you cannot force sleep, there is a lot you can do to promote it.

Behaviors that promote restorative sleep are designed to support your sleep drive and body clock. These behaviors support current restorative patterns, and encourage alterations in sleep patterns that have gotten dysregulated. They work at strengthening the body clock and the sleep drive, as well as the dance between the two.

In contrast to behaviors, there is not a prescribed set of sleep-promoting thoughts. It is not possible to force positive thoughts about sleep, or to simply will yourself to sleep. Check in with people who are sleeping well and you will hear them say that they do not think about sleep very much at all. Their general attitude reflects a sense of trust in the process of sleep. On the other hand, you, along with most people who are not sleeping well, probably think quite a bit about sleep. Or maybe you have a busy mind that keeps you up at night. Either way, these thoughts tend to be activating. This impacts the body clock in a way that can interfere with the “ideal” alignment of the sleep drive and body clock depicted in figure 2.1.

We want to help you support your body’s natural capacity to sleep. We do this in chapters 6–9 by reviewing behavioral programs designed to promote sleep. In chapters 4 and 10–12, we will help you think more like confident sleepers do.

Your Next Step

Sleep is the product of complex relationships between the internal regulators in your brain, cues from the environment, and your behaviors and thoughts. These are ever-changing, dynamic relationships that have natural fluctuations. For example, your internal body clock changes over the course of your lifespan, with notable shifts in adolescence and late adulthood. You are exposed to more daylight in the summer and less in the winter. And life events are sure to interfere with “ideal” sleep-related behaviors and thought patterns. You will stay up late or wake up early to meet deadlines, tend to sick family members, spend time with family and friends, read wonderful books, or play enjoyable video games. These disruptions often are not avoidable. Even if they were, we would not want you to avoid life! We encourage you to check in with yourself to assess if you are sleeping to live, or living to sleep.

Fortunately, your body is designed to navigate these challenges. Sometimes you will return to restorative sleep right away. Other times, it may take a few days or weeks to restore your sleep-wake pattern. But rest assured, your body is well equipped to function in the real world.

If we are designed to manage these variations, why is it that we have such an epidemic of poor sleep in our culture? What is happening that your body is not able to resolve your sleep disturbance the way it is designed to? In the next chapter we will help you understand why your brain has not self-corrected, and you are instead stuck in an insomnia spiral.

Figure 2.1. The 2-Wave Model of the Physiology of Sleep

Figure 2.1. The 2-Wave Model of the Physiology of Sleep