Chapter 3

The Insomnia Spiral

If we all have sleep disruptions from time to time, and our bodies are designed to navigate these challenges and self-correct, how is it that you are experiencing ongoing problems with insomnia? In this chapter we will answer this question by describing the 3P model of insomnia (Glovinsky & Spielman, 2006). We will then illustrate it with a case example. Finally, you will complete an exercise to make the model personal to you.

The 3P model, along with the two-wave model that you learned about in the last chapter, provides the rationale for all of the treatment recommendations we will be making in this book. We are sure you are eager to dive into treatment. Still, we encourage you not to skip this chapter! In our experience, this education will help you better understand the various treatment elements of this program. And this understanding can make all the difference in your willingness to do the treatment fully. Understanding the rationale also will allow you to make informed choices about when and how much to deviate from the recommended guidelines, and how to adapt the treatment in challenging circumstances.

As you work through this chapter, continue to complete your sleep log. You soon will use all the data you have been collecting!

How People Get Stuck

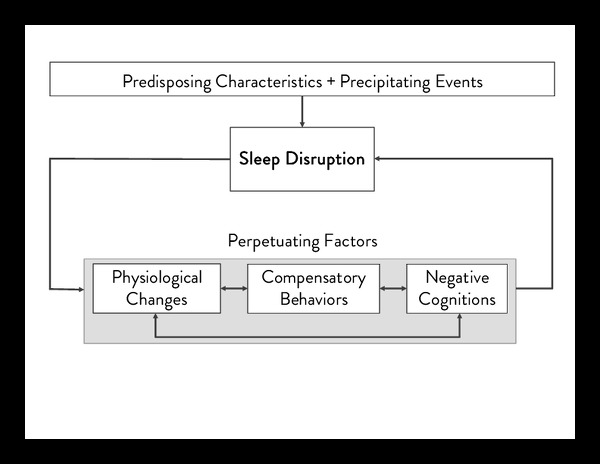

The 3P model of insomnia provides a framework for understanding how insomnia starts and how people get stuck. The three P’s stand for predisposing characteristics, precipitating events, and perpetuating factors (namely attitudes and practices). As you read this section, refer to figure 3.1 for a visual depiction of the model.

The basic idea is that we all have characteristics that predispose us to develop a particular type of sleep problem. “Predispose” means to come before. Predisposing characteristics are present before you have a chronic sleep problem. They are risk factors. They may be traits that you were born with (such as being a “night owl” or a “high-energy” person) or that you acquired over time (such as an injury, or age). Predisposing characteristics do not automatically interfere with sleep, but they make it more likely that you will have sleep troubles. In less technical terms, we think of predisposing characteristics as “What You Had” leading up to your insomnia journey.

Precipitating events are whatever kicked off your sleep problems. These may be life events (such as becoming a parent or losing a job) or a biological process (such as menopause or an enlarged prostate). We like to think of precipitating events as “What Life Gave You.”

“Precipitate” means to cause. In truth, precipitating events interact with your predisposing characteristics to create sleep disruption. For example, you may say something like: “I was always a bit of a night owl, but it was never really a problem until I took my first office job. Suddenly I had to be up by 7. I was exhausted by 11 p.m., but sleep just wouldn’t come. I would lie in bed for hours.” In this scenario, being a night owl predisposed you to—or put you at risk for—developing a sleep problem. Having to shift your schedule precipitated—or triggered—the insomnia. Here is another example: “I was always a light sleeper [predisposing characteristic], but I didn’t have sleep problems until I had to sleep in a noisy dorm in college [precipitating event]. Now I have a nice, quiet home, but I still can’t sleep.”

As you have been reading, perhaps your mind quickly identified “What You Had” and “What Life Gave You.” Maybe there is no way to change some or all of these things. Or maybe you do not want to change your triggers, such as working in a field with demanding hours, or having children. Or perhaps you have no idea why you developed insomnia, or why you developed it when you did.

Do not despair! You do not need to know, or be able to change, what caused your insomnia in order to treat it. Remember, our bodies are designed to self-correct—and sleep—even in the face of “What Life Gave You.” Many people who are under tremendous physical or emotional stress have only a night or two of poor sleep. Then something in their brain says, Sorry, pal, I need to sleep. And they do. And many other people get back on track with sleep as soon as the trigger resolves, such as moving out of a noisy environment. So the real question is not why you experienced sleep disruption in the first place. The million-dollar question is, Why did you get stuck?

This brings us to the third “P,” perpetuating attitudes and practices, or “What You Do.” These are the thoughts you have and things you do in response to your insomnia. Your thoughts may be completely natural. Your actions may be completely sensible as you try to compensate for sleep loss. Natural. Sensible. Yet unhelpful, or even counterproductive. How can this be? This is because sleep is like skiing the trees. The interventions that help sleep get back on track are often counterintuitive. Choices we make to provide short-term relief in the moment (such as going back to bed, or taking naps) may work against what the body needs to return to its natural patterns (such as building a stronger sleep drive to get it back in sync with your body clock). This turns into a vicious spiral. We are trying to feel better and when our choices are not effective, over time we experience feelings such as anxiety, frustration, disappointment, and anger. These feelings then produce tension, which interferes with sleep. We continue to have poor sleep and we naturally have thoughts such as, I will never sleep, Tomorrow is going to be awful, and Nothing is going to work. This makes it even more likely that we will continue to choose behaviors that might provide some short-term relief but that, over time, confuse the body clock and deplete the sleep drive, maintaining our sleep problems. And the spiral continues.

A Case Example: How George Got Stuck

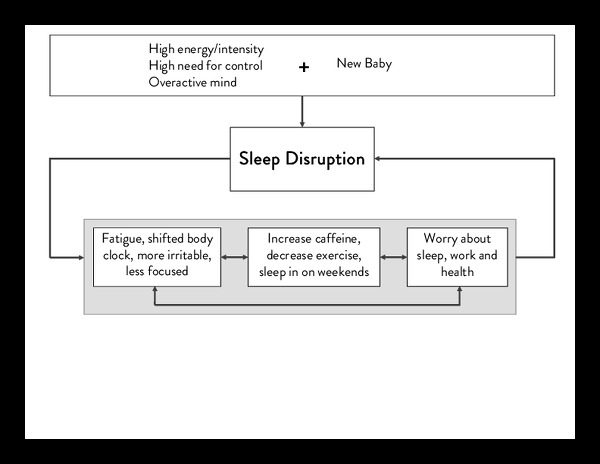

What George had. George is an active businessman who is always on the go. He runs an advertising agency and bikes five miles to and from work. He prides himself on his quick mind, working long hours, being creative, running a “tight ship,” being liked and respected by his employees, and still having time and energy to spend with his wife and children. He generally sleeps well, and feels rested on seven hours of sleep each night. On occasion, he struggles to wind down from the day. On these nights, his mind is busy and his body is taut with energy as bedtime approaches. A little reading settles him down, and he falls asleep soon after he turns out the lights. We can describe George’s predisposing characteristics as: high energy/intensity, high need for control, physiological hyperarousal, and an overactive mind (also known as “cognitive hyperarousal”).

What life gave George. Five years into running his business, George and his wife decide to have a third child. They are very excited! However, their new baby has colic, and fusses much of the night. George finds that, even when it is his wife’s turn to be up soothing the baby, he has trouble sleeping. Once he is awakened by the baby, he starts thinking about issues at work and how to solve them. It is 3 a.m., but his brain will not turn off. Although he has the opportunity to sleep approximately six hours per night, he is only averaging about five hours. He now has insomnia. His insomnia was triggered by caring for a newborn. Many parents in this situation would be sleep deprived because of the decreased opportunity to sleep, but would nevertheless sleep soundly when not up with the baby. George was vulnerable to this event triggering insomnia, and not just sleep deprivation, because of his overactive mind.

At this point, George’s sleep problems are new. We can expect that they will resolve as soon as the baby starts sleeping better. It also is likely that George’s sleep will get better even before his baby’s sleep improves, as his brain’s natural ability to adapt kicks in. George is confident that, like his other two children, this baby will learn to sleep, and then his own sleep patterns will be restored.

What George did. George was right about his baby’s sleep improving. Six months later, she is sleeping much better. George is not. He wakes up most nights around 3 a.m., and his mind immediately starts thinking about work. Sometimes he remains in bed, tossing and turning, and finally getting some light, fitful sleep in the hour before the alarm sounds. Other nights he gets up and works at the computer.

Not surprisingly, George is really fatigued. His mind still moves quickly, but in a more frenetic kind of way. He feels less focused, and is a bit more forgetful. He tries to put on a bright face for his children, but his family can tell that he is less exuberant, and sometimes even a little irritable, with them.

George now has a chronic problem. He does what any of us would: he tries to fix it. George tries to manage his fatigue by sleeping in on weekends. He drives to work rather than biking. He gradually starts to drink more caffeine, hoping to get more energy and focus. He stops drinking alcohol, and has a regular wind-down period at bedtime. His disrupted sleep continues. He is confused about what is going on. He starts to feel anxious, and worries about the effects this sleep deprivation may be having on his business, and on his body.

Notice in figure 3.2 that What George Did impacted his sleep physiology. For example, his body clock is now primed to see 3 a.m. as a time to be awake and working. His body clock shifts when he drinks more caffeine, and when he conserves energy by reducing his exercise. Worrying about his insomnia further arouses him. What George Did also impacts his sleep drive. Sleeping in on the weekends depletes his sleep drive as he heads into Sunday night. He is so sleep deprived that his sleep drive still is higher than his alerting force at bedtime, so he falls asleep easily. However, because it starts at a lower place, his sleep drive is depleted enough by 3 a.m. that it cannot trump the message he is getting from his body clock to wake up and think about work. The body clock’s alerting force spikes up above the sleep drive, and George awakens and cannot get back to sleep. He faces another Monday of sleepiness and difficulty focusing, and reaches for extra caffeine to get him through the day. And the cycle continues.

The very things George has been doing to help himself have now become a part of the problem. And the longer this pattern of thoughts, behaviors, and physiological changes persists, the more new data George’s body is getting, and the more it will adapt to his new patterns, moving him further and further away from his more natural and workable sleep-wake pattern.

Exercise: How Did You Get Stuck?

Use worksheet 3.1 to take a close look at your own 3P’s. What made you vulnerable (predisposed you) to developing insomnia? What, if anything, seemed to trigger (precipitate) your initial sleep problems? How are you responding to your unreliable sleep? Here are some typical things we hear. These are not exhaustive lists, so do not limit yourself to these examples when you complete the worksheet.

What I Had:

|

Poor sleeper all my life |

“Light” sleeper |

Worry or fret a lot |

|

Chronic pain/discomfort |

Depression |

Anxiety |

|

Hormonal fluctuations |

“Type A” personality |

High energy/intensity |

|

High need for control |

A body that tends to be ready for action (physiological hyperarousal) |

A very active mind (cognitive hyperarousal) |

What Life Gave Me:

|

Birth of a child |

Death of a loved one |

Increase in daily stress |

|

Job promotion |

Job loss |

Moved |

|

Financial hardship |

Financial windfall |

High conflict with someone |

|

Health concerns/problems |

Onset of menopause |

Start or end of a relationship |

What I Did to Handle Sleep Disruption:

Catch up on sleep by sleeping in on the weekends

Nap

Watch the clock at night and get concerned as time passes

Spend more time in bed

Skip exercise the day after a poor night’s sleep

Drink alcohol to sleep

Cancel activities when I have not slept well

Avoid scheduling morning activities for fear I won’t feel up to them

Take sleeping medications

Avoid scheduling evening activities for fear they will interfere with sleep

Watch television or play video games when I can’t sleep.

Eat in middle of night

Increase caffeine/stimulants

A Balancing Act

Remember that “What You Had” consists of one or more risk factors, because these variables do not automatically interfere with the process of restorative sleep. Similarly, “What Life Gave You” may or may not impact your sleep. This variable, like the first, makes you more vulnerable to sleep problems. Similarly, no one thing that you did or thought in response to your sleep disruption is likely to be causing your sleep problems. It is all a delicate balancing act.

We use the equal-arms scale to illustrate this point. An equal-arms scale is the type of old-fashioned scale that has a beam anchored in the middle with one “arm” on each side of the beam. When you put objects on each arm, the arm with the heavier objects will tip down while the lighter side moves up.

On one side of our scale are things that promote or support restorative sleep. This includes aspects of your body clock and your sleep drive that are functioning well, and all the thoughts and behaviors that support and promote your sleep cycle. As long as this side of the scale is “heaviest,” you will have restorative sleep. On the other side of the scale are all the variables that challenge restorative sleep. Medical and mental health issues, current environmental stressors, and the thoughts and behaviors that undermine or sabotage sleep are on this side of the scale. As long as this side of the scale is the heaviest, you will have sleep problems.

Stopping the Spiral

Throughout this chapter we have explored how your thoughts and behaviors interact with your physiology and sleep patterns. There is actually one more layer involved—time. The longer the spiral of thoughts, behaviors, and physiological changes persists, the more your body will pay attention. It is getting new data about your patterns of wake and sleep. So it does what bodies do. It adapts. Your body creates a new pattern based on the current cues from the body and the environment. It recalibrates and starts to identify these current trends as a new pattern. Sometimes this pattern has a known rhythm to it (such as napping during the day and awakening every night at 3 a.m.), and sometimes there is no obvious rhythm, so that you never know if this will be a “good night” or a “bad night.” The common theme is that you no longer have predictable, restorative sleep.

Fortunately, we can change What We Do, and this is exactly what helps stop the spiral of chronic insomnia. CBT-I is focused on helping you identify the behaviors and thought patterns that were natural responses to your sleep problems but that have, inadvertently, “backfired” and become part of the problem. All of the interventions in CBT-I share the common goal of helping you reconnect and stay connected to the automatic and natural rhythms of your body. In chapter 5 we will build on the work you did in this chapter to help you choose the interventions best suited to stopping your spiral, so that you can return to a more restorative sleep pattern.

But first we must turn our attention to the topic of willingness. Remember our metaphor of skiing the trees? The end result of working on this skill is to become aware that you are in a forest that presents more risk than skiing on an open trail, and yet still be able to resist your urge to hyperfocus on the trees. Now you have a relationship with the entire mountain. This relationship is not built overnight, but over time, through consistent practice, skills, and willingness. Successful sleep is similar. Your relationship with sleep is lifelong, and you will do best when you are aware not just of this one night, this one urge, or this one feeling, but also are aware of how your choices today will impact your long-term sleep pattern. Although this paradigm shift is not part of classic CBT-I, we have found that it is essential to decreasing your struggle with sleep and supporting your willingness to do CBT-I.

Figure 3.2. George’s 3P Model of Insomnia

Figure 3.2. George’s 3P Model of Insomnia Worksheet 3.1: Your 3P Model of Insomnia

Worksheet 3.1: Your 3P Model of Insomnia