Our suffragist meetings have become rather monotonous. The men have stopped attending, and the women would rather discuss the new ice rink in Madison Square Garden than the ratification of the state constitution. They are more intrigued by the new five and dime store, Woolworth’s in New York, than the new bill allowing female attorneys to discuss cases before the U.S. Supreme Court. I am even more discouraged when I learn that a high number of citizens in our county don’t pay taxes. I believe in the basic strength of our government, so I quietly begin paying my taxes again.

Mrs. Manor, a sometimes suffragist, travels in loftier social circles than I do. Nonetheless, our paths cross from time to time. Often, her son, James Henry, accompanies her. For years we nod and comment on how the boys have grown, how nicely behaved they are, how polite. During meetings, James Henry Manor and Marion played together as children. As young adults, they sit demurely and discuss issues of vast importance to no one but them. I begin to wonder if Marion is falling in love.

But James Henry Manor has his eyes on another, and I notice before Marion does. When I see him at meetings now, his gaze follows Ellie, not Marion. He is more likely to be present if Ellie is also there. I watch Marion closely, but her face is neutral. After a meeting one evening, Marion and I walk home together. My son has stayed home to study, as he does more often than not these days. Ellie walks ahead with James Henry, her laugh floating back to us. I peek at Marion without turning my head toward her. She scowls.

“Why aren’t you walking with Ellie and James Henry?” I ask. She knows I’m not stupid, but that comment doesn’t prove it.

“He’s in love with her.” Her tone tells me nothing about her feelings.

“I don’t know, Mary, I think he has feelings for you, too. He’s spent a lot of time with you.”

“I was there. He was there. It was easy. But this…” she motions toward her sister. “This is different. He’s like a puppy begging for a ball to be thrown.”

“Ellie seems happy,” I venture. It’s an understatement. My daughter comes alive when she catches a glimpse of young Mr. Manor.

“I suppose.”

I can’t stand this any more. I stop and face her. “Mary, do you love him?”

An incredulous look of shock spreads over her face. “Mama, I introduced them! How could you think I would love James Henry? He’s as much a brother to me as Henry is. I wish Ellie well.”

“Then why do you seem so morose?”

She laughs. “Is that what this is? You think I’m pining for my sister’s beau? No, Mama, I merely miss time spent with a friend. I have no desire to marry.”

We continue walking in silence. I am glad on many levels that my daughters will not be competing for a man. I cannot bear the thought of our days being taken up with the shallowness of such a competition, nor do I want to see either of my daughters hurt.

When eventually Ellie becomes engaged to James Henry Manor, I still find it difficult to reconcile the boy, seashells in his pockets and sand his hair, with the young man who makes my daughter’s eyes glow. Marion is as pleased with their match as if she alone was responsible, even though she is not a proponent of the state of marriage.

At the wedding in January of 1879, I sit misty-eyed with memories of my own weddings and husbands; the hope and promise of dear Jacob, and the businesslike necessity of Henry.

Marion sits with me in the church pew, her face solemn. “She’s beautiful and happy, but I can’t help but think she’s throwing her life away,” she whispers.

“No, Mary, she is making a different choice than you are. That’s all. Marriage is not for all of us, but maybe it is for Ellie.”

“It will tie her down to her husband’s wishes and the demands of her children,” Marion insists.

I lay my hand on her leg in reassurance. “And that may be the life that pleases her, as it does many. It is her choice. Be happy for her. It is possible to work for a cause and be married. In fact, most of our leaders have husbands and families.”

“If Papa hadn’t died, would you be just a wife and mother?”

I pause to consider the tone of her words, the derision faint but present, and wonder what sort of memories my daughter has of her father. “A wife and mother can be a powerful position,” I tell her.

Ellie floats down the aisle in a vision of white satin, white lace, and pearls. Her veil is a cloud on her blond hair, and her blue eyes shine like sapphires. I marvel that such a creature is my daughter. Henry is best man. He and James Henry are dashing in their fine clothes. The elite of Santa Cruz are here to witness this wedding and attend the reception afterwards where they will toast the newlyweds. L’Amie and Simeon come in from Los Gatos on the train. All is laughter and joy. My words to Marion are solid mothering, but in my deepest heart I wonder. And worry as only a mother can.

But Ellie blooms. James Henry sets off each morning to his produce store in town, and she cooks and cleans and flits about society as if she’d been trained for that and nothing more. The nation’s economy is recovering from a post-war depression, and her future is bright. She draws me into her whirlwind for a time, first as the mother of the bride then as the grandmother-to-be. Ellie often sends a servant around to collect almond butter that I make from the tree in my yard. Her newly acquired social position as Mrs Manor the younger requires her presence at a number of soirees where my almond butter is appreciated. Often I attend with her.

One day that summer, I assist Ellie in the kitchen. She is with child and preparing for a luncheon with five of her friends. She slices cucumbers paper-thin for sandwiches. My job is to remove the crusts from the white bread and spread the slices with butter.

“So how are you feeling, dear?” I ask. “Has the morning sickness passed?”

She nods. “Yes, Mama, I feel much better. I think of you going to Papa’s mill every day in this condition and I cannot imagine how strong you must have been.”

“It’s truly a vindication of my effort to hear that,” I say with a smile.

An hour later, Ellie and her friends are nibbling sandwiches and sipping tea. I note only to myself that they are imitating a custom already grown cold in Britain. I am conscious of being older than them, and feel so wise.

“Oh but you simply must engage a nursemaid,” one of the young ladies is saying. I think her mother attends my meetings.

“Raising your own baby is so exhausting,” another affirms. She looks as if she has never changed a diaper in her life. Her nails are perfect, and not a hair on her head is out of place.

“James Henry’s family has a nanny we will use,” Ellie says. I am proud of her quiet confidence. She doesn’t have to remind these young women that the Manor family could afford three nannies.

I am tired of nannies. “Have any of you heard that the Susan B. Anthony Amendment was defeated in Congress?”

They look at the wall, the floor, anywhere but me. They sip their tea. Ellie leans toward me and says gently, as you would to an old woman, “Mama, that was months ago. You know Senator Sargent will introduce it again.”

They wait a long moment. Then the animation returns to their faces and they begin discussing fall fashion. It is all I can do to subside into silence, struggling to comprehend how this round of shallow interactions with women of no depth can fulfill one’s soul.

Harder still is comprehending, three months later, the miracle of my first grandchild, Harold, born a proper ten months after his parents’ wedding. I thank God for vanquishing the diphtheria epidemic that took all four of Mrs. Hind’s children just before this precious bundle arrived.

At the tender age of three weeks, I hold the tiny bundle in my arms. He is swaddled tightly in a blue blanket crocheted by his mother, his eyes squeezed shut. He yawns, his tiny mouth resembling a hungry bird’s.

“Ah Harold,” I murmur.

Ellie is as starstruck as I am. “We call him Hal, Mama.”

“Hello, little Hal,” I croon. I am smitten long before he smiles at me.

“Married life and motherhood agree with you, Ellie,” I tell her as I hand the baby back to be fed.

She beams, but directs it at her son. “He’s perfect, Mama. I want a dozen more!”

“That’s a lot of babies, dear.” I laugh with her. “And this fills you, Ellie?” She darts a quizzical look at me, and I remember the first months of motherhood. “Your time is filled, I know, and your heart, but your soul?”

“I don’t know what you mean.” Her brow furrows and her mouth frowns. The tone of her voice is sharp.

With her blond hair swept back and pinned up, and her starched apron, she is every bit the mother. Maybe the fire in her soul burns for this, is fueled by the day to day tasks of raising children. It is too early to tell. “Never mind, honey, he is beautiful.”

“Mama, not everyone is brave like you,” she tells me, with what appears to be sympathy in her eyes.

Now it’s my turn to feign ignorance. “What do you mean?”

“Women’s rights are important to you. While I was growing up you were always pushing for reform. Abolish slavery, temperance, the vote—always some wrong that needed to be put right.” She tucks the blanket closer around Hal, then looks right at me. “Were you ever happy, Mama? If Papa hadn’t died would you have had more children and stayed home more?”

Happy? A montage of past moments plays through my mind, of sandy children at the beach, of dolls and laughter and picnics in the yard. Yes, I was happy, but I am stung to waspishness. “Would you have rather had a mother like Mrs. Manor?”

Ellie grimaces, but polishes her features back to neutrality. I know she is not fond of her vapid mother-in-law. “Mama, your substance is not in question here. Maybe you should look at your motives. Who are you really striving to right the world for? Me? Or you? Did it ever occur to you that I may not want to vote?”

“I will never force you to vote against your will,” I tell her. I cannot control the edge to my voice, and I know it won’t help. I try for a smoother tone. “My efforts are all about giving you the choice.”

Without smiling or responding, she takes Hal from me and escapes into the nursery to feed him, leaving me alone with my thoughts.

When Marion was born, I felt complete for awhile. Then I became pregnant again, and Ellie’s birth filled my time. Amusing a baby and a toddler chased notions of any other use of my time right out of my head. My husband’s death threw me into the business world, and I hardly noticed my last pregnancy. That taste of the greater world ruined me as a full-time mother. Would I have been content had I not stepped up to run the mill? Or if Henry hadn’t died? That is water under the bridge, as they say. My eyes, my heart, my soul, were opened and will not be shut. I am in a position to make a difference for those who are unable to help themselves, and so I must.

Later that evening at home, I am still pensive. Marion brings me a cup of tea and I smile my thanks.

“Hal is a cute little fellow,” Marion says, taking a seat near me.

I am fully aware that she senses my mood and is testing to see where my thoughts are dwelling. “Yes, he is. Not for you, though?”

She shakes her head.

“My children are a great joy to me, Mary. I grieve that you choose not to know the same joy.”

“I will share Ellie’s children,” she says, “and Henry’s.” There is no hint of loss in her tone or expression.

In fact, we both smile at the notion of Henry having children. Although he approaches adulthood, he is still a child himself in so many ways.

“I am content, Mama.”

“As am I, my dear.” I don’t want my daughter to think I disapprove of her choice not to marry, and I am well aware that her decision could change with a simple introduction to the right man. I refuse to do as my own mother did and push every eligible man at her. But by doing so have I limited her choices? I can only do as I see fit.

My children are certainly capable, but only Marion shares my passion for women’s rights. I consider the women I know in our little town. Many of them dabble in political causes to fill their social calendars. I don’t think it matters to them if it is the vote for women or homes for stray kittens. Their world is limited to their family, focused on raising happy healthy children and creating a pleasant home. I cannot fault them for that any more than I personally can be content with that life. I only hope that someday Ellie sees value in a political cause, and Marion sees value in a family.

Daughters stay close to their mothers. My mother lived with me, or with my sister, until she passed away. Marion still lives with me. Hal is a son, though, and destined to leave. My brother left home at seventeen and made only quick visits after that. His home was never again with us. Even my son has gone to Hayward to work on his cousin’s farm. Seventeen must be the age of separation for young men. They feel they are adults, but their mothers see only children striking out alone in the world. It is a lonely thing to watch your youngest child seek their future alone, and I am glad I have my politics to fill my heart. I wonder where Hal will be at seventeen.

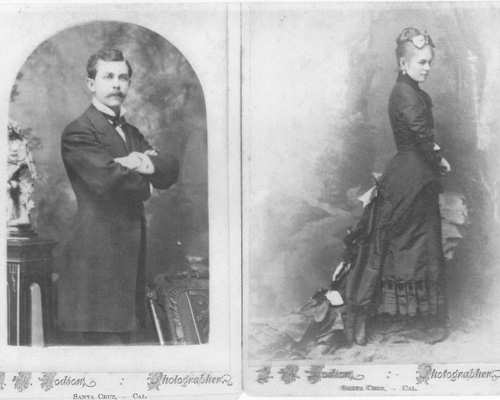

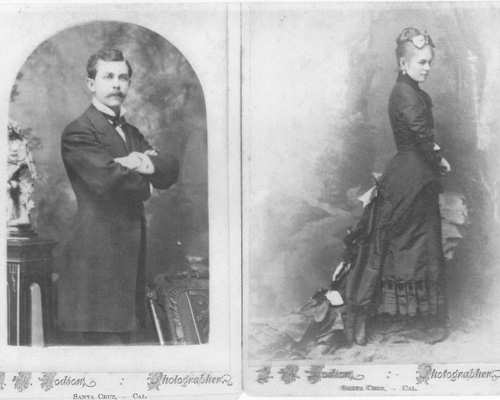

Wedding photo of James Henry Manor and Ellie VanValkenburgh, J.R. Richard Photographer, Santa Cruz