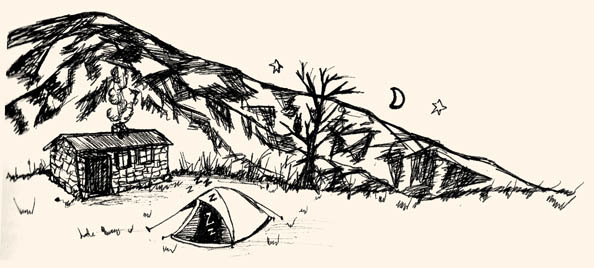

Arriving at Dulyn bothy in the Carneddau

Standing stones, hut circles, hill forts – ever since the Stone Age humans have descended on the valleys and mountains of the Carneddau, attempting to tame it. With the sea visible from its northern flanks and the higher Snowdonian peaks poking out at its southern end, the range is a perfectly placed vantage point from which to admire the surrounding landscape.

Not that the Carneddau don’t offer height themselves. Here sit seven of the highest hills in Wales, their banks a rolling mass of splintered rock, left behind from retreating ice over 400 million years ago. Carving through the grass and soil, in the valleys below the giants, are winding rivers, babbling and sputtering as they descend the hillsides or spill out from the reservoirs that sit beneath the amphitheatre of sheer cliffs.

One such patch of water is Llyn Dulyn, which pools below the craggy corners of Craig y Dulyn before rising up to the summits of Foel Grach and Carnedd Gwenllian (formerly known as Carnedd Uchaf). Its name translates as ’black lake’, and a visit to this particular part of the Carneddau will reveal why. Sinking to an estimated depth of around 60m, its waters appear dark and mysterious. Dig a little deeper and you’ll discover it’s been the site of several light-aircraft crashes due to the sudden height gain after a lower valley and the mist that such a place so often attracts. Llyn Dulyn is an eye-catching landmark to visit in its own right, but what makes it even more attractive to walkers is that a few hundred metres from its edge sits an old hut, now known as Dulyn bothy.

Thought to be a shepherd’s hut, or remnants of workers’ quarters built when they were damming the lake (which supplies water to the nearby town of Conwy), it is a cosy two-roomed affair that sits in arguably one of the wildest-feeling areas in the northern end of the national park.

Your walk-in alone will tell you that this is not the first homestead to sit among these mountains. En route you’ll be able to make out the old boundary walls of earlier farms. Look over to the peak of Drum and you’ll spy standing stones and circles, and if you head out along the river moss-covered remains of old settlements and sheepfolds will litter your route.

At the bothy itself, though, the presence of human neighbours feels a whole world away. You don’t get the crowds here that you will at the adjacent Ogwen valley, or the summer tourists that flock to Llanberis and Snowdon. No, here you can often find yourself quite alone...and it’s simply wonderful.

Did you know?

For at least 500 years the Carneddau has been home to a unique population of wild ponies, which the Carneddau Mountain Pony Association is working to have protected as a rare breed. They belong to no one, but each year are rounded up by the local community to be counted. Although a very difficult winter in 2013 saw at least 50 die, the last count showed healthy numvbers. And although you are by no means guaranteed to see them on a visit here, they are worth keeping an eye out for.

Half-light. That odd time of the evening when your eyes can play tricks on you – bushes become sheep, metres seem like miles and that shape of a building you’re peering down the valley hoping to spy keeps morphing into nothing more than another cluster of boulders.

It was this time of evening that I set off from the car to pay another visit to Dulyn bothy. The first time I saw it was several years before. I had been hoping to find it for an overnight sleep, arrived from Carnedd Dafydd too late, and instead wild camped next to Melynllyn. It was only the next morning when I walked out to the car that I spied the bothy and realised just how close I had been to it. I made myself a promise to return.

Now I walked, straining my eyes against the deepening purple sky, trying to spot it once more. My boots crunched on the gravel as I paced the ground, the moon above now beginning to offer more glow than the dying rays of daylight. Then, deep in the valley below I saw it, its stone walls visible against the rock-covered grass it sat on. I quickened my pace, eager to reach it before dark.

Every step I took felt like I was merely bobbing up and down rather than striding forwards. Soon I became impatient, and despite the clumps of heather I struck right, heading directly towards it. The sodden hillsides tugged at my boots as I descended the heather rising around me, up to my waist and occasionally my cheek, but still I continued, the bothy now sharpening into focus. Summoning up my strength I leapt across the river on a series of protruding rocks then stumbled up the slopes and made a left – I was going to make it.

The rhythmic sound of snoring alerted me to the fact that I was not going to get this place to myself. Outside the door a tent was pitched on the flattened grass, the occupant already sound asleep. I crept on by, knocked on the door and opened it to a group of ruddy-faced bothy-dwellers, their skin made red from the glow of the fire and the plates of pasta they were eating.

’Come on in,’ the one over the camping stove welcomed, and I was presented almost immediately with a plate of hot food and offered a seat by the fire. The smell of the pasta blended with the scent of a damp building being made warm in a summer evening, and I felt instantly at home.

Conversation began, and it transpired that one of them was the Maintenance Officer from the MBA. As we talked and I peered around the building I realised with a sinking heart that once more a stay in the bothy would elude me – it was full.

I went outside and admired my surroundings from the doorstep, which had now become drained of colour in the pallid tones of pre-darkness. I knew I could have squeezed in that night but I made my excuses and left, deciding to camp instead.

As my headtorch lit the way ahead I glanced back over my shoulder to my hosts. It was amazing how four simple walls could transform into a cosy shelter in an isolated valley and become instantly alive with the banter that comes from the gathering of strangers in a wild place. Despite a chill in the evening I felt a warmth running through my body and couldn’t help but smile.

Vegetation: The hardy plants that call these hills home range from Welsh poppies to bilberry, twisted hawthorn, holly and rowan – there’s lots to take in if you keep your eyes peeled.

History: What you can’t fail to see in the Carneddau are relics from the Stone, Bronze and Iron Ages, whose people littered these peaks with a mix of standing stones, circular stone huts and cairns. Although many are now just impressions of what used to stand there, or stones scattered on the ground, they are a testament to the fortitude of the people who used to live and farm these Welsh highlands.

Classic: The shortest way is from the car park near Llyn Eigiau. Finding the car park can be tricky – but it’s via the small lane heading uphill next to the bridge in Tal-y-bont. Once you’ve left your vehicle simply follow the well-maintained track around the bump of Clogwynyreryr and along to the water at Melynllyn. Here you veer north to pick up the path over to the Dulyn Reservoir, cross the river, and the bothy is about 300m east of it.

Time: 1½hrs

The main sleeping room

Candles and stoves provide light and heat in bothies such as Dulyn

Top tip

Directly outside is some flatter ground (in front of the building) that you could feasibly pitch a two-man tent on. Otherwise, the flat ground next to Melynllyn is perfect for a wild camp.

Hard: Those wanting to maximise their hills could approach the bothy from the A5 in the Ogwen valley. A track opposite Gwern Gof Isaf leads up to Pen yr Helgi Du and on to Carnedd Llewelyn and Foel Grach, from where you can take the path down towards Melynllyn, go off-piste towards the water and then pick up the path to Dulyn Reservoir and the bothy. Harder still – and really packing in the ascent and mountain peaks – would be to pick up the path further west down the A5, opposite Ogwen Cottage, and start by ascending Pen yr Ole Wen and Carnedd Dafydd, then go on to Carnedd Llewelyn and continue as per above.

Dulyn essentials

| Maps | OS Explorer 17; OS Landranger 115 |

| Grid ref | SH 705 664 |

| Terrain | Wide and well-defined track towards Melynllyn, then rougher, boggy ground to get to the bothy. A river crossing is involved, but this is usually straightforward. |

| Water source | The nearby Afon Dulyn flows below the bothy |

| Facilities | Coal fire (bring your own fuel); shovel |

| Building | Stone construction; metal roof |

| Inside | There are two rooms. After coming through a small porch you enter the main room. This is large and offers tables, chairs, a fire, an array of pots and pans left by other bothy users and candleholders on shelves. On your right is a door leading into the sleeping area. There are no raised platforms here, just a large space that could easily sleep 10 comfortably on the floor (more if you were prepared to snuggle!). |

| Nearby hills | Foel Fras, Carnedd Gwenllian, Foel Grach, Carnedd Llewelyn, Yr Elen |