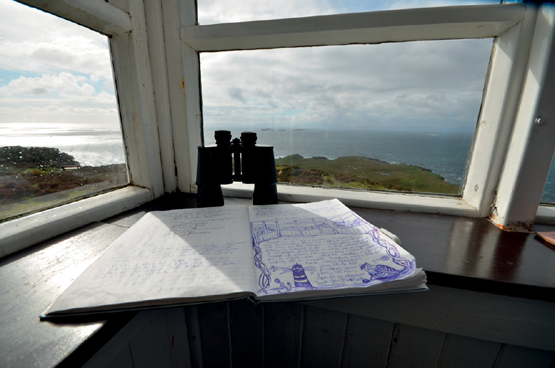

Something I love about this bothy, and every bothy, is how a network of adventurers and travellers is created through these pages. We may never meet. David, Owen and their friends who stayed here on the 5th October may never meet the famous Izzy and Rose who stayed here from 1–3 October, but there’s a connection there... something happened between them, even though separated by time, they are united by place.

Entry in Grwyne Fawr bothy book, by ’Hannah’, 2013

My face was stained orange by the flame. The flickering glow of a dying candle fizzed and spat as I leafed through the pages of a bothy book – the visitors’ log that’s placed in each and every shelter from the far north of Scotland to the forested valley of mid-Wales which makes up the bothy network. I was, at the particular moment, not really aware of my surroundings. Wasn’t taking in the view of the creeping valley at my window as a thin sliver of a river hewed its way through the undergrowth and tipped into the dam below it. Didn’t register the shrill hoot of a brown owl on the hunt in the clear sky above my little slate roof. Instead I was lost among the pages of this tome, caught in a space between time by Hannah’s words, meeting new people in the ink within the lines of paper. This is the power of the bothy book, and of the bothy itself – this ability for visitors to simultaneously find and lose themselves, to meet and connect with other people in a way that they never could in an office or house surrounded by mod cons and mobile phone reception.

But first, perhaps, I should rewind. I was in a bothy – a mountain hut that’s completely free to use as an overnight stop, positioned in a wild and stunning location. Somewhere you could go and stay tomorrow and not pay a penny for the privilege.

I know all too well how novel the idea of a bothy can sound to the uninitiated. The notion that landowners, who will make no money from it, will leave one of their buildings unlocked for walkers, climbers or outdoor enthusiasts to sleep in can sound bizarre. Furthermore, when you learn that an organisation regularly raises money to maintain these buildings and furnishes them with basics like a fireplace or stove, a table and a visitors’ book, it seems even more outlandish. But that’s exactly what the Mountain Bothies Association (MBA) – a donation-funded and volunteer-run organisation which has just celebrated its 50th anniversary – does to this day.

Bothies have a knack of bringing out both the best and the worst in people. Don’t believe me? Head to a popular one, close to a city, on a Monday night, and you might, if you’re unlucky, find piles of rubbish on the sleeping platforms, questionable yellow liquid in bottles above the fireplace and a visitors’ book filled with senseless scrawl. But, equally, there’s not another place in the world I can name where I’ve arrived in a storm, uninvited, and instantly been offered dry clothes, the comfiest armchair closest to the fire (forcing someone else to stand), and warm food and drink I didn’t bring myself.

Two extremes? Definitely. But I stand by my assertion that something happens to us when we venture into the wild, the remote, the isolated. Social barriers break down, we have time to think, time to reflect, and the opportunity to do things right – not through fear of being punished if we don’t, but because we get a feeling so good from doing them that we want to do them more and more. And it’s in those places that you’ll find bothies.

Until five years ago the MBA didn’t publish locations of their bothies online – they remained a secret for members and those in the know. But word got out, as it always does, and so they decided it was time to share them. Some disagree with the idea – think that it’s best that few people know their whereabouts because they operate within a system of trust. There’s nothing to stop someone ruining them for others.

Given that, you might wonder why I too have decided to publish details of some of these shelters myself in this book. The reason is simple – I want more eyes on them, more eyes to watch over them and keep them safe. The kind of person hell-bent on destroying a bothy is certainly not going to bother with a book when they can find the location of just about any bothy in the country with a quick search on Google.

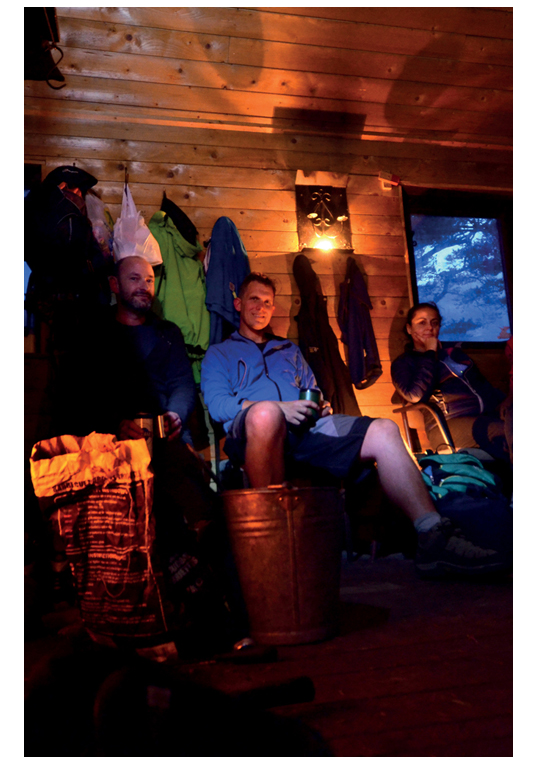

Warm fires and mountain adventures are shared by candlelight

The kind of person I want to tell about bothies is you. I want to invite you all to fall in love with these modest shelters as much as I have. I want to share the information I know about them, want to help you reach them the best way possible, would like you to be prepared for staying at them and, finally, I want to take you on a journey to visit them over the next couple of hundred pages so that, even if you don’t get chance to visit them all, you’ll feel like you have.

As the wise Hannah said – we may never meet, but through these bothies we will be connected, a network of travellers and adventurers created through these pages.

The easiest way to describe bothies is simply as stone tents. They may look like country cottages from the outside – pretty enough, with a ramshackle type of charm to earn them a spot on chocolate boxes – but inside it’s a different story. With no gas, no electric, no running water, no bathroom, no beds and certainly no TV, these are as basic a shelter as they come. But it’s amazing what a few candles, a lit fire and good cheer can do to a place.

In terms of size, bothies range from two-person shed-like affairs right up to multi-bedroom house-like structures with several fireplaces and even kitchen areas. There isn’t a standard bothy – they will constantly surprise you – but therein lies their charm.

Best of all they are left unlocked on a trust basis, for wilderness lovers to stay in, so that we might linger in the places we love so well. It’s funny how somewhere so basic that it wouldn’t even make a hotel grading system can be a place with views that are definitely five star.

Bothies can be found all over Britain in wild and remote places. Because of this, most are found in Scotland – arguably home to the wildest tracts of land in mainland Britain – with a few scattered in the north of England and parts of rural Wales.

To give you an idea of their distribution, the MBA has around 100 buildings in its care, of which just eight are in Wales (where the MBA is known as the CLLM) and 10 in England. The selection of bothies in this book reflects this northern bias.

Chatas, Alpenvereinshütten, cabins, wilderness huts, backcountry bunks – even if you’ve never stayed at a British bothy you will probably have heard of one of their foreign cousins. So the idea of staying out in the mountains or wild hinterland is certainly not a new one.

Glencoul, in Sutherland, is just one of the many bothies in Scotland that is ideally placed beside a loch

The Swiss Alpine Club has built huts for climbers and walkers since 1863, offering refuge and respite for those far from civilization. The Appalachian Mountain Club in North America constructed its first backcountry shelter in 1888. And places around the world from Norway to New Zealand, and from Poland to Patagonia, are home to a network of cabins that provide a bed for the night for weary travellers.

Where the bothies in Britain differ is that they were never built for that purpose, but rather were appropriated when that need arose. Originally old farmsteads or workers’ huts, they existed because employees on big remote estates, or those quarrying or building dams deep in the mountains, needed somewhere to rest or stay nearby – a commute would have been impossible.

However, the arrival of cheaper vehicles, agricultural machinery and greater transport links meant there was no longer a need for people to reside in these far-flung corners of the country. One by one they began to leave their homesteads behind, quarrying fell out of demand and workers’ quarters were no longer inhabited.

Around the same time, in the 1930s, came the Great Depression, a time when industrial workers’ hours were becoming shorter, giving the working classes more leisure time but little money to spend on it. Most of them were stuck in factories during the hours they did work, and longed to escape the cities. Naturally the mountains were calling. Mass trespasses began to take place – famously in the English Peak District on Kinder Scout, but also beyond – by which men and women demanded their right to roam in the empty swathes of land that surrounded them. Climbing clubs cropped up all over the country, but especially in Scotland, and more specifically Glasgow, where the famous Creagh Dhu club was formed in Clydebank.

Hutchison Memorial Hut in the Cairngorms is popular with climbers

For its members, getting into these wild spaces was more than just a hobby, it was what they needed to enable them to survive working in industrialised urban environments for the remaining five (or more) days each week. Putting on shared buses or, more often, hitchhiking, once they got where they needed to go, short on money, they would sleep wherever they could – in barns, under rocky overhangs (known as howffs), in caves and in these abandoned bothies, and they taught themselves to live off the land, so that they could be close to the crags the next day.

This spawned some of the most famous climbers of the 20th century – from Jimmy Bell (who put up a host of new routes on Ben Nevis and edited the Scottish Mountaineering Club Journal for an impressive 24 years) to WH Murray, author of Mountaineering in Scotland (first penned on toilet paper when Murray was a prisoner of war during the Second World War, it was destroyed by his captors, to which he retaliated by writing it again and finally – triumphantly – getting it published in 1947), and Don Whillans (working-class hero, incredible climber, gear inventor and renowned deliverer of the one-liner). For men such as these, bothies were key to enabling them to get into the countryside and stay on the doorstep of the peaks.

In the years after the Second World War society’s attitude to the outdoors and, more specifically, outdoor activities was changing too. Soldiers and their families looked to camping as a cheap holiday, and more and more people were discovering that walking was a therapeutic way to spend their increasing free time.

Some more intrepid walkers and mountaineers began to explore their own country’s wild corners, and as they did, those other than climbers stumbled upon these abandoned buildings. Giving them a convenient start point for a mountain ascent, walk or crag climb the following day, many began to stay the night in them – sometimes with and sometimes without the landowner’s consent. And thus the modern day bothy-er was born.

But an ill-maintained building can survive only so long, and soon many of these bothies crumbled into ruin. Some were adopted by climbing clubs that knew of their importance; others were lucky enough to have landowners who privately maintained them for outdoor enthusiasts and local shepherds. But many others were left abandoned. And so they would have remained were it not for one man, Bernard Heath. It was he who, back in 1965, got together with a group of friends to repair and restore the old farm building in Dumfries and Galloway now known as Tunskeen bothy. Later that year a group of like-minded bothy-lovers joined forces, and the Mountain Bothies Association we know and love was formed.

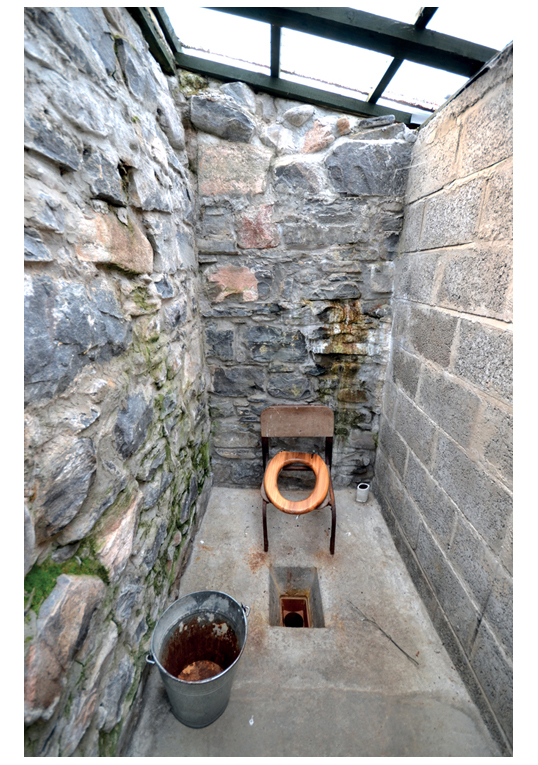

Toilets in or near bothies are a welcome addition – but should by no means be expected!

Membership grew (as did bothy projects), Maintenance Officers (MOs) were appointed in the 1970s, in 1975 the charity was officially registered, and in 1991 Bernard and Betty Heath were honoured with a British Empire Medal for their work.

Changes may have taken place over the years, with health and safety legislation being addressed, complaints procedures being established and company status being updated. But its purpose remains unchanged. Some 100 bothies, over 2000 members, regular work parties and 50 years later, the volunteer-run organisation is still working hard with landowners to preserve and restore ’open shelters for the use and enjoyment of all who love wild and lonely places’. And thank goodness they do.

The association’s founders once wrote that: ’Members’ only reward will be the knowledge that their efforts have helped save a bothy from ruin.’ And how many of us would want anything more?

Basically none. In fact, if you get four walls and a roof that doesn’t leak then you should count yourself lucky. In my experience it’s much better to go with low expectations and be pleasantly surprised, rather than to go expecting a Hilton and find a low-rent shack.

Many bothies will, of course, have something more in them, ranging from the basic (chairs, tables) to the more upmarket (sleeping platforms, a stove, a river nearby) and the downright luxurious (toilet, water pipe just outside, reading material, bed frames).

Go prepared for the worst. Even if you’ve read something about a bothy in this book, remember that things change, break or are removed – so be prepared. Expect the walk to the nearest water source to be a trek and bring a bigger container to minimise your trips to collect it; assume the fire won’t work and bring an extra layer and a hat to sleep in; know that there won’t be any toilet paper so bring your own.

Follow this simple rule and you will avoid any disappointment.

It’s a fair question, and one my friends and even family members frequently ask me. Aside from the obvious – that I love them, and once you get the bothy bug you can’t stop going to them (I swear it’s worse than being a Munro-bagger) – it’s really the same reason that you go wild camping, or even just walking. It’s to get away from everything and enjoy discovering the uncrowded and rugged corners of a beautiful country.

Of course, you can do exactly the same thing with a trusty bivvy bag or tent, so below is a list I’ve drawn up to show the pros and cons of staying in a bothy versus a tent. I’ll leave it to you to decide the best...

- Warmth You can have a fire and get warm.

- Space Rather than being stuck in a cramped crouch of a tent, trying to get undressed without touching the sides of your condensation-drenched walls, you have the luxury of space to manoeuvre, stretch – even dance if the mood takes you.

- Drying out Got caught out in the rain? At a bothy you can dry your clothes out above a fire or spread your belongings out on a table and let them dry.

- Escaping midges Bothies are usually home to spiders, and spiders mean fewer midges, so you can cook and eat your evening meal without getting bitten.

- People You may meet people with a similar love of the outdoors.

- Inside information Fellow visitors may share the location of other bothies or wild camp spots for you to discover.

- Mice A mainstay of nearly every bothy, you are guaranteed to hear at least one at some point in your bothying experiences – make sure you pack your food away before you go to sleep.

- People Although a few like-minded souls can be good, too many can be frustrating – staying up too late, being loud, not understanding the boundaries of personal space, snoring.

- Poop Where there’s lots of people there can sometimes be a toilet issue; put a foot wrong and the consequences could be dire.

Conclusion: Do use bothies, but take a tent or bivvy bag as a back-up – that way the choice is yours...

If you’re serious, the first thing you should do is join the MBA. At the time of writing, membership is a tiny £20 per year, with a reduced rate of £10 to under 16s, over 60s and the unemployed (see www.mountainbothies.org.uk for current prices). The money you give goes straight into the pot to pay for maintenance work – so you can stay at your next bothy and know that your contribution made a difference. You’ll get a members’ handbook, a regular newsletter and the annual report.

Skirting the reservoir en route to Arenig Fawr bothy, Snowdonia

This book is a good first step to finding a bothy, but before you head out get a good map – Ordnance Survey or Harvey Maps (if available). Using the grid reference find your bothy and then plot the best route there for you, based on your experience.

Then, pack the proper kit (see ’What to take’, below) and get out there and find it. I’ll warn you – some are easy to find, whereas others are more difficult. Many bothy-lovers will (or at least soon will) know the pain of wandering around tired after a long walk-in, mere metres from the spot where the bothy should be, in horrendous weather, mistaking boulder after boulder as the promised bothy (I’m looking at you, Hutchison Memorial Hut – if you come from the Linn of Dee approach). But the more you visit, the more confident you’ll get, and you might even find bothies not under the care of the MBA...

Not all bothies that exist do so under the umbrella of the MBA. Look at an OS map, in any of the wilder areas of Scotland, Wales and England, away from towns and cities, and you will see a number of tiny shelters marked on it. Of course that doesn’t mean that a) it’s actually a bothy or, perhaps more importantly, that b) it’s even there at all. Time is harsh to buildings in wild places. Wind, rain, ice and snow will eventually take their toll, and many a would-be bothy has been destroyed over the years completely unintentionally, because a landowner cannot afford to maintain a building that has no real purpose for them.

On the other hand, I’ve often stumbled upon a bothy belonging to a landowner, and equally as often it has been kept beautifully by the walkers who find and use it. The non-MBA bothies, of course, tend to be hard to find. But, and I guarantee this, the more that you use bothies the more you will find that are out there. Bothy-dwellers are a generous bunch, and having sussed out that you’re a responsible sort will often share with you other locations. So while all but one of the bothies in this book are maintained by the MBA (as denoted by the circular white MBA sign on the front door), it’s hoped that this book will serve as a starting point, a kicking-off into the wonderful world of bothies, from where you will discover more than you ever imagined.

Always take a tent or bivvy in case the bothy is full – particularly when visiting smaller bothies such as the Hutchison Memorial Hut

- Rucksack (suggest around 40–50 litres)

- Sleeping mat (if yours is inflatable and prone to puncture consider bringing a ground sheet)

- Sleeping bag (in winter consider taking a liner for extra warmth)

- Tent/bivvy (as a back-up)

- Camping stove

- Gas

- Spork (fork, knife, spoon combination)

- Mug

- First aid kit (don’t forget the blister plasters and tick remover/tweezers)

- Map (OS Landranger (1:50,000), Explorer (1:25,000) or Harvey – relevant maps are indicated in each chapter)

- Headtorch (with new batteries inside)

- Warm gloves, hat and buff

- Fleece/midlayer

- Waterproof jacket

- Waterproof overtrousers

- Insulated jacket (down or synthetic)

- Dry bag containing: toothbrush and paste, dry socks, change of underwear, tissues

- Toilet paper

- Sanitary products (if applicable)

- Disposal bag for toilet paper/sanitary products/general waste

- Hand sanitiser

- Water bottle (for purified water only)

- Water container (collapsible, wide-mouthed is best) for collecting stream water

- Food

- Candles (tea lights) and lighter/matches

- Fuel (see ’A note on fuel’ below) and small amount of kindling for the fire

- Midge repellent (trust me, you’d rather have it and not need it than need it and not have it)

- Pen for filling in the bothy book

Craig bothy, Torridon

- In winter consider taking down booties – those nights can get cold!

A note on fuel

Most (although not all) bothies have either an open fire or a multi-fuel stove. This book indicates whether or not the featured bothies have one. If they do, it’s strongly advised that – unless indicated otherwise in the relevant chapter – you take in your own fuel. So what to take? Coal is the obvious choice – it burns longer and hotter than wood and stores heat well – although it is heavy, of course. If you decide on coal, consider getting the smokeless variety. Wood is the other option, although a bag of wood is a lot bulkier than coal. If you decide on wood, a better option is wood briquettes (also known as ’heat logs’), which are compact and often have a guaranteed burn time of 1–2hrs.

If you forget to take fuel, think very carefully about what to use. Never cut live trees – only ever use dead wood. Don’t chop up furniture/shelves inside the bothy to burn. It may be annoying to forget fuel – we’ve all done it – but please still be a responsible user.

The former Warden’s Room in Craig bothy, Torridon, offers a luxury overnight experience

Much like wild camping, to be a good bothy guest you need to follow good etiquette. Members of the MBA follow a Bothy Code of Conduct, but you don’t need to be a member to be a responsible bothy user. Simply follow this fairly common-sense set of guidelines.

- Look after your bothy From tiding up food after you make it to taking out rubbish someone else has left behind – it’s all about doing as much as you can to make bothying a great experience for everyone else. So if you’ve got room left in your backpack, take out that rubbish that was there when you arrived – even if it’s not yours.

- ...and look after its surroundings This book indicates when a stove or fireplace is present, and also when you should bring your own fuel – so you can go prepared. Please don’t cut live trees or nearby fences for your fire, and don’t light a fire outside the bothy.

- Everybody’s got to go, but... When you need the toilet, be courteous. If there is a toilet (which is rare, but some have them) follow the instructions to the letter. If it says not to drop down anything but tissue and human waste, then don’t throw down a wet wipe. If it asks you to refill the bowl from the stream once you’ve flushed, then fill the bowl from the stream when you’ve finished – no matter what the weather. In the much more likely case that there is no toilet, note the spade in the corner. It’s there for entirely this reason – make sure you use it. When you do, remember these simple steps:

- Go at least 200m away from the bothy, at least 50m from a path and definitely at least 50m from a watercourse (it is, after all, likely to be the place where you’ll want to source your drinking water), and downstream of the bothy.

- Try to carry your own waste out with you (places like the Cairngorms operate a Poo Pot scheme – pick up a Poo Pot from the ranger base and return it there for disposal – and dry-bag manufacturers make bags for the same purpose).

- If you can’t carry out your own waste, bury it, even in winter. Using the spade, dig a hole at least 15cm deep (if there’s snow on the ground, it needs to be a hole in the ground below the snow to stop an unwelcome surprise for other walkers in spring) and go in that.

- Carry out all your toilet paper and any sanitary products (remember to take a special bag for this in your rucksack) and cover the hole.

- Remember to wash your hands – antiseptic hand sanitiser is the best method as no water is required.

This friendly sign hangs on the door of every bothy in the MBA network

- Make sure everyone is welcome It’s not first come, first served; bothies are there for everyone to use, so try to accommodate everyone who turns up – no one should be left out in the cold. Don’t like crowds? Take your own tent or bivvy to give yourself a Plan B.

- Be generous... to a point While it’s good to leave things for the next guest – be sensible. A few pieces of coal, some firelighters or tinder is great; rubbish that you think would work as kindling and can’t be bothered to carry out, not so good. Want to share your food? Think about it – what food would you be prepared to eat when you don’t know the source? Unopened tinned food – yes; a half-eaten bag of nuts – no. And remember mice are frequent visitors too; don’t encourage them by leaving opened food.

- Don’t outstay your welcome If an estate asks users not to visit the bothy at certain times of the year, it’s for a good reason. So respect their wishes, and if they ask you to call ahead to check it’s safe – then do it.

- Keep it brief The whole point of a bothy is that it’s a temporary refuge for walkers – so keep walking. Don’t turn up and set up home there for a week. One or two nights is fine, but any longer and you’ll need to ask permission first. There are plenty more bothies anyway, so get exploring rather than settling in the same one.

- Keep it to the minimum Bothies are not the place for large groups. With other users turning up all the time, you cannot arrive en masse and expect to fit. A maximum group size should be six or fewer. Any more and you will need to ask for permission from the owner first.

- When you leave, go gracefully Check the fire is out, and if it’s not, put it out – never leave it unattended. Close the door – cattle, deer and birds can all get inside if you leave it open, but then can’t get back out. And take rubbish with you.

The main risk in a bothy is from the fire. Stoves and open fires are a welcome facility, but if you leave a fire unattended, burn the wrong thing or – worse – have a faulty stove or chimney the consequences can be dire.

Check before you start your fire that there is nothing in the fire/stove that shouldn’t be – plastics, tins, and painted or varnished wood are a definite no-no. Remove these if you find them. Make sure there’s no masonry from the chimney in the grate – this could be a sign the chimney is faulty.

When you do start the fire keep a lookout for smoke seeping out where it shouldn’t – from panels or from part-way up the chimney or flue. If this happens, or if the room fills with smoke, put the fire out, open the windows or doors, leave the bothy and do not enter until it’s clear – CO2 poisoning is a killer.

If using a stove make sure the ash pan is empty before you start and empty it the next day before you leave.

Do not leave a fire unattended, and make sure the fire is out when you leave.

Most bothies are near a water source (river or stream), and this is indicated within each bothy chapter. While there are many people who swear they drink from these without treating the water first, and have always been fine, it’s best to err on the side of caution.

The simplest way to purify water is by boiling it on your camping stove. Once you’ve brought it to the boil be sure to let the water roll for a couple of minutes before using it. If you want to save fuel take chlorine tablets with you or consider carrying in a water filter/purifier device, though these can be a bulkier option.

Whatever method you choose, take fast-flowing water (as opposed to standing water) from as close to the source as possible.

As good a read as any book you’ll ever find, these wonderful pages contain days’, months’ and years’ worth of other people’s adventures. They will sometimes shock, sometimes make you laugh, often be a cryptic puzzle about the person who was here before you, but they are always sure to inspire you to go somewhere new and read another one.

Some bothy locations – such as that of The Lookout on the Isle of Skye – can bring out the artist in us

I’ve seen everything from poetry to illustrations, book extracts and even a 16-page polemic about why the outdoors shouldn’t be regulated. Each one is a gem that, if I had my way, would find its way into the National Archives. Better yet – they are all unique. They give a sense of the characters who’ve slept in the same four walls as you and tell a lot about the type of people who seek out the different ones – from the popular bothies, where lots of newcomers visit and Duke of Edinburgh groups stop for lunch, to the hard-to-reach ones where the entries are more sombre affairs full of advice and plans for the days ahead.

In each of the following chapters you’ll find my own bothy-book entry – a personal account of a memorable experience at that particular place.

Make sure, whenever you visit a bothy, you fill the bothy book in and become part of the wonderful legacy.

Enjoying a coffee in Ruigh Aiteachain bothy, East Highlands

Apart from writing in the bothy book – which should be mandatory (consider taking a pen in case there isn’t one or it’s run out) – many walkers often share whisky from a Sigg bottle, which I’ve done on more than one occasion. But if you don’t fancy that, your tradition could be being kind to any other users who come along. And while we’re talking new traditions, the best approach you can take at a bothy – whether you’re staying for a couple of minutes to look around, half an hour for a lunch break, or one or two nights – is always to leave it in a better state than when you arrived. Because if we all did that, we’d always find every bothy in a clean and well-maintained state.

Bothies are maintained by volunteers, who can’t always get out to them as often as they’d like. That means you can be their eyes and ears on the ground. Once you’ve visited a bothy contact the MBA via the website (www.mountainbothies.org.uk, ’Make a Report’ section) and let them know if vital work needs doing. If something’s missing – such as a shovel – tell them. If someone’s tried to burn a chair – tell them. Or even if everything seems in order just tell them – it’s nice for them to know.

Common things that go wrong with bothies are roofs, windows, doors and floors. So on your next visit take a look around. Are there tiles missing on the roof? Is water dripping inside when it rains? Are all the windows intact? Is the door still on the stove? Is the floor OK – no holes or soft spots underfoot? Do any of the walls, ceilings or floors have visible cracks? Is the front door closing properly and staying closed?

If you notice anything tell the MBA so that they can sort it before things get worse – a minor problem can easily develop into a major expense if not addressed.

Saws, often supplied at the bothy, are useful for cutting dead wood for the bothy fire

Then, perhaps consider joining one of the regular work parties held throughout the year all over the bothy network. You can help restore one of your favourite shelters, meet other bothy-goers and get to spend a weekend in one of the best spots in Britain.