CHAPTER 1

Why We Are Alienated From Ourselves

Our intellectual world is made up of categories, it is bordered by arbitrary and artificial frontiers.

We need to build bridges, but for that there is a need for knowledge, a greater vision of man and his destiny.

YEHUDI MENUHIN

U.S. and British violinist and conductor

Preamble

I have no words to describe my loneliness, my sadness, or my anger.

I have no words to speak my need for exchange, understanding, recognition.

So I criticize, I insult, or I strike.

Or I have my fix, abuse alcohol, or get depressed.

Violence, expressed within or without, results from a lack of vocabulary; it is the expression of a frustration that has no words to express it.

And there are good reasons for that; most of us have not acquired a vocabulary for our inner life. We never learned to describe accurately what we were feeling and what needs we had. Since childhood, however, we have learned a host of words. We can talk about history, geography, mathematics, science, or literature; we can describe computer technology or sporting technique and hold forth on the economy or the law. But the words for life within … when did we learn them? As we grew up, we became alienated from our feelings and needs in an attempt to listen to those of our mother and father, brothers and sisters, schoolteachers, et al.: “Do as Mommy tells you … Do whatever your cousin who’s coming to play with you this afternoon wants … Do what is expected of you.”

And it was thus that we started to listen to the feelings and needs of everyone—boss, customer, neighbor, colleagues—except ourselves! To survive and fit in, we thought we had to be cut off from ourselves.

Then one day the payment comes due for such alienation! Shyness, depression, misgivings, hesitations in reaching decisions, inability to choose, difficulties to commit, a loss of taste for life. Help! We circle ‘round and ‘round like the water draining from a sink. We are about to go under. We are waiting for someone to drag us out, to be given instructions, and yet, at the same time, recommendations aren’t exactly welcome! We’re snowed under with “You must do this … It’s high time you did that … You should …”

What we need most of all is to get in touch with ourselves, to seek a solid grounding in ourselves, to feel within that it is we who are speaking, we who decide and not our habits, our conditioning, our fears of another’s opinion. But how?

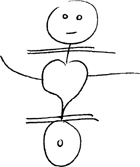

I like to introduce the process that I advocate by using the picture of a little man born of the imagination of Hélène Domergue, a trainer in Nonviolent Communication in Geneva, Switzerland.

-

(or observation)

Feelings

Needs

(or values)

The request

(or concrete and negotiable action)

1. Intellect (or observation)

Intellect

Judgments, labels, categories

Prejudices, a prioris, rote beliefs, automatic reflexes

Binary system or duality

Language of diminished responsibility

The head symbolizes mind. The main beneficiary of our educating is the mind. It’s the mind that we have honed, toned, and disciplined in order to be effective, productive, and fast. Yet our heart, our emotional life, our inner life, has not enjoyed such attention. Indeed, we learned to be good and reasonable, to make well-thought-out decisions, to analyze, categorize, and label all things and place them in separate drawers. We have become masters of logic and reasoning and, since childhood, what has been stimulated, exercised, refined, and nuanced is our intellectual understanding of things. As for our emotional understanding, it has been encouraged little or not at all, if not overtly reproved.

Now, in the course of my work, I observe four characteristics of the functioning of the mind that are often the cause of the violence we do to ourselves and others.

Judgments, labels, and categories

We judge. We judge others or situations as a function of the little we have seen of them, and we take the little we have seen for the whole. For example, we see a boy in the street whose hair is orange and combed into a crest; he has his face pierced in various places. “Oh, a punk, another rebel, a dropout feeding off society.” In a flash, we have judged, faster than the sun creates our shadow. We know nothing about this person, who is perhaps passionately engaged in a youth movement, a drama troupe, or computer research and who is thus contributing his talent and his heart to the evolution of the world. However, as something about his looks, his difference, generates fear, mistrust, and needs in us that we’re unable to decipher (perhaps the need to welcome difference, the need for belonging, the need to be reassured that difference does not bring about separation), we judge him. Look how our judging does violence to beauty, generosity, the wealth that may well lie within this person whom we have not seen.

Another example. We see an elegant woman dressed in a fur coat, driving a large car. “What a snob! Just another woman who can’t think of anything better to do than display her riches!”

Again, we judge, taking the little we have seen of another for her reality. We lock her into a little drawer, wrap her up in cellophane. Once again, we do violence to the whole beauty of this person, which we have not perceived because it lies within. This person is perhaps quite generous with her time and money, and she may be engaged in social work, giving support to destitute people, or pursuing other unknown endeavors. We know nothing about her. Once again, her looks awaken fear, mistrust, anger, or sadness in us and put us in touch with needs that we don’t know how to decode (need for exchange, need for sharing, need for human beings to contribute actively to the common good) as we judge, so we imprison others within a category; we close them away in drawers.

We take the tip of the iceberg for the whole, whereas another part of us realizes that 90 percent of the iceberg is under the surface of the sea, out of sight. It is worth recalling the words of Saint-Exupéry, author of The Little Prince, “We only see well with our hearts; what is truly important is invisible to our eyes.” Do we really look at others with our hearts?

Prejudices, a prioris, rote beliefs, automatic reflexes

We have learned to function out of habit, to automate thinking, to presumptively have prejudices and a prioris, to live in a universe of concepts and ideas, and to fabricate or propagate unverified beliefs:

Men are macho.

Women can’t drive.

Officials are lazy.

Politicians are corrupt.

You have to fight in life.

There are things that have to be done, whether one wants to or not. That’s the way it always has been done.

A good mother, a good husband, a good son … must …

My wife would never put up with me speaking to her like that. In this family, one can certainly not raise an issue like that.

My father is someone who …

These are expressions that basically reflect our fears. Using them, we enclose ourselves and others in beliefs, habits, concepts.

Once again, we do violence to the men who are anything but macho, who are open to their sensitivities, their kindness, the nurturing “feminine” that lies within them. We do violence to the women who drive much better than most men, having both more respect for other motorists and greater safety in traffic. We do violence to the officials who give of themselves generously and enthusiastically through their work. We do violence to the politicians who do their jobs with loyalty and integrity, working idealistically and selflessly for the common good. We do violence to ourselves and others regarding all the things that we dare not speak or do, whereas they are truly important for us, as well as for the things we believe we “have to” do without taking the time to check whether they indeed are a high priority or whether we might better take care of the true needs of the people concerned (those of others or our own) in some different way.

Binary system or duality

When all is said and done, most of us have gotten into the all-too-comfortable habit of expressing things in terms of black and white, positive and negative. A door has to be open or closed; something is good or bad; one is right or wrong. This is done or that is not done. It is fashionable, or it is obsolete. It is just great or absolute rubbish. There are subtle variations on the theme: You are intellectual or manual, a mathematician or an artist, a responsible father or a free spirit, a social butterfly or a couch potato, a poet or an engineer, a homo or a hetero, “with it” or a fuddy-duddy. This is the trap of duality, the binary system.

Most of us have gotten into the all-too-comfortable habit of expressing things in terms of black and white, positive and negative.

It’s as if we could not possibly be both a brilliant intellectual and an effective manual worker, a rigorous mathematician and an imaginative artist, a being both responsible and fanciful, a sensitive poet and an earnest engineer. It’s as if we could not possibly love ourselves beyond our male/female sexual duality, be conventional in some areas and highly innovative in others.

Stated another way, it’s as if reality were not infinitely more rich and colored than our poor little categories, these tiny drawers into which we try to stuff reality because its mobility, diversity, and enchanting vitality disconcert and frighten us. In order to gain reassurance, we seem to prefer to lock everything away in apothecaries’ pots, carefully labeled and placed on the shelves of our intellect!

The logic of exclusion and division is something we practice on the basis of or. We play at “Who is right, who is wrong?”—a tragic game that stigmatizes everything that divides us rather than extolling the value of what unites us. Later we will see to what extent we allow ourselves to be trapped by the binary system and what violence it perpetrates on ourselves and others. The most frequent example is the following: Either we take care of others, or we take care of ourselves, with the consequence that either we are alienated from ourselves, or we are alienated from others—as if we couldn’t possibly take care of others and take care of ourselves while being close to others without ceasing to be close to ourselves.

Language of diminished responsibility

We use a language that allows us not to feel responsible for what we’re experiencing or for what we are doing. First of all, we have learned to project onto others or onto an outside agency most of the responsibility for our feelings. “I am angry because you … I am sad because my parents … I am depressed because the world, the pollution, the ozone layer …” We take little or no responsibility for what we are feeling. On the contrary, we find a scapegoat, we make heads roll, we off-load our negative energy onto someone else who serves as a lightning rod for our frustrations! Then we also have learned not to take responsibility for our acts. For example: “It’s the rule … Orders from above … Tradition has it that … I wasn’t able to do otherwise … You must … I have no choice … It’s time … It is (not) normal that …”

We will see to what extent this language alienates us from ourselves and from others and enslaves us all the more subtly as it appears to be a language of diminished responsibility.

2. Feelings

Through this traditional way of functioning, which sets mental processes at a premium, we are cut off from our feelings and emotions by something as effectively as by a concrete slab.

Perhaps to some degree you will recognize yourself in what appears below. Personally, I learned to be a good and reasonable little boy, ever listening to others. Speaking of oneself or one’s emotions in regard to self was not well-received when I was a child. One could describe with emotions a painting or a garden, speak of a piece of music, a book, or a landscape, but speaking of oneself, especially with any emotion, was tantamount to being tainted with egocentricity, narcissism, navel-gazing. “It isn’t right to be busy with oneself; it is others whom we should attend to,” I was told.

If one day I was very angry and expressed it, I might hear something like: “It isn’t nice to be angry … A good little boy doesn’t get angry … Go to your bedroom and come back when you have thought things over.” Back to reason.

I thought things over with my head, which wasted no time in judging me guilty. So I then cut myself off from my heart and put my anger in my pocket and went downstairs to redeem my place in the family community by displaying a contrived smile. If another day I was sad and unable to hold back my tears, suddenly shaken by one of those heavy moods that can fall upon you without understanding why, and I just needed reassuring and comforting, I would hear: “It’s not nice to be sad. Just think of everything that is done for you! And then there are people who are really unfortunate and who don’t have nearly as much as you do. Go to your room. You can come back when you have thought things over.” Dismissed again!

I would go to my room, and the same rational process would predominate: “It’s true, I have no right to be sad. I have a father, a mother, brothers and sisters, books for school and toys, a house, and food. What am I complaining about? What is all this, this sadness? I’m so selfish. Useless idiot!” Once again, I judged myself and found myself guilty, alienating myself from my heart. Sadness went off to join anger in my pocket, and I went to redeem my place in the family, displaying another contrived smile. So you can see how early we learn to be nice rather than genuine.

Finally, another day when I was brimming over with joy, exploding with happiness and expressing it by running around, playing my stereo full blast, and singing and talking nonstop, I would hear the following words: “What’s wrong with you? Life is no spring picnic!” My goodness, that was the death knell! Even joy wasn’t welcome among adults! So what did I do then as a ten-year-old lad? I entered the following two messages on my internal hard drive:

To be an adult is to cut oneself off as much as possible from one’s emotions and use them only once in a while to produce the right effect in a party conversation.

To be loved and have my place in the world, I must not do what I feel like doing, but what others want me to do. To be truly myself runs the risk of losing the love of others.

This data-entry operation generates several factors of conditioning that we will explore further in Chapter 5.

Yes but, I hear you say, is it really necessary to give a warm reception to all these emotions? Might we not run the risk of being manipulated by our emotions? You are doubtless thinking of some people who have been angry for fifty years and who have been wallowing in their anger without taking a single step forward—or others who are sad or homesick and dwell incessantly and morosely on their perceived problems, with little hope of escape. Still others rebel against everything and drag around their rebellion like a ball and chain, without ever finding peace. Indeed, swimming perpetually in one’s feelings brings no development and may even induce nausea.

Our emotions are like waves of multiple feelings, pleasant or unpleasant, that are useful to identify and distinguish. It is useful to identify our feelings because they inform us about ourselves and invite us to identify our needs. Feelings operate like a flashing light on a dashboard, indicating that something is or is not operating properly, that a need is or is not being met.

As we are so often cut off from our feelings, we tend to have few words to describe them. On the one hand, we may feel good, happy, relieved, relaxed; on the other, we may feel fearful, rotten, disappointed, sad, angry. We have such a paucity of words to describe ourselves, and nonetheless we still function. In Nonviolent Communication training sessions, a list of more than two hundred fifty feelings is handed out to participants to enable them to expand their word power and, in so doing, broaden the consciousness of what they are feeling. This list doesn’t draw its words from an encyclopedia or thesaurus. Rather, it is a glossary of common words that we read daily in newspapers or hear on television. However, a sense of propriety and reserve handed down from generation to generation in most families prevents us from using them when speaking about ourselves.

Developing our vocabulary expands our ability to deal with what we are experiencing.

Much of what we learn from infancy onward plays a part in developing our awareness of subject matters or fields of interest that lie outside ourselves. As noted in the preamble, we become quite proficient at learning history, geography, and mathematics, and later we can specialize in plumbing, electricity, data processing, or medicine. We develop a vocabulary in all sorts of areas, and we thus acquire a certain mastery, a certain ease with which to deal with these matters.

Acquiring vocabulary goes hand in hand with developing awareness; it is because we have learned to name elements and differentiate among them that we can understand how they interact—and modify such interaction as necessary. Personally, I don’t understand much about plumbing, and when my water heater doesn’t switch on, I call a plumber and tell him what the problem is. My level of awareness of the elements at play and my ability to act on them are pretty close to zero. As for the plumber, he will identify what is going on and express that in practical terms: “The burner is dead” or “The pipes are scaled up, and the gas injector has had it.” This gives the plumber power to act and, in this case, power to repair.

When I was still a practicing lawyer and received people in my office who were muddled, confused, and powerless when faced with legal difficulties, I experienced pleasure in sorting out the matters at stake, seeing how they interacted, defining priorities, and thus being in a position of strength to propose a way forward. Power of action is therefore tied to awareness and the ability to name elements and differentiate among them. Each of us has thus learned to exercise a degree of power of action in areas outside ourselves.

However, when in our education did we learn to name what was at stake in our inner life? When did we learn to become aware of what was going on within us, to distinguish and sort through our feelings, as well as our basic needs, to name those needs and then simply and flexibly make concrete and negotiable requests, taking into account the needs of others? How often do we feel helpless, even rebellious, at the powerlessness we experience relating to our anger, sadness, or nostalgia—feelings overflowing within us, poisoning us like some venom—without being able to react? To our feelings of being ill at ease and angry, sad or nostalgic, are now added discomfort and helplessness: “Not only am I unhappy or angry, I also don’t know what to do to get out of it.”

Often “to get out of it” we can only blame someone or something: Daddy, Mommy, the school, buddies, colleagues, clients, job, the state, pollution, the slump. Having neither understanding of nor control over our inner lives, we find a party outside ourselves to serve as a scapegoat for our pain. “I am angry because you … I am sad because you … I am disgusted because the world …”

We export our difficulty, we off-load it onto someone or something else as we are unable to process it ourselves. On the other hand, to be able to process what is happening within us, we need to develop a vocabulary of feelings and needs in order to become more at ease with the method. Little by little we gain mastery, which is not suffocation of our true needs and feelings. Instead, it is appropriate management of them.

Feelings act like a blinking light on a dashboard or control panel. They inform us about a need: A pleasant feeling shows that a need is being met; an unpleasant feeling indicates an unmet need. It is therefore invaluable to be aware of this key distinction in order to identify what one needs. For, rather than complaining about what I do not want and often asking someone incompetent to help, I will be able to clarify what I want (my need rather than my lack) and to inform a competent person in order to get help—this person most often being “yours truly”!

Feelings act like a blinking light on a dashboard; they tell us that an inner need is or is not being met.

Here is an example I give at conferences: I am driving my car along a country road, and I may find myself in one of the following three situations:

I am driving an old car with no control panel, like a Model T Ford of the early 1900s. I’m driving along confidently, using up all the reserve gasoline and have no concern for my need for gas (since there is nothing to alert my awareness). Sooner or later I run out of gas in the middle of the countryside—no signal, no awareness of the need, no power to act.

A more conventional scenario: I’m driving a modern-day car that has a fully equipped dashboard. At some stage, my gas gauge shows me that I’m on reserve. So I complain: “Who forgot to put gas in this car? It’s simply unbelievable; it always happens to me! Isn’t there anyone besides me in this family who can think about filling up?” I complain and complain, so much so that I’m totally absorbed by my complaining and fail to see all the gas stations I drive past. Sooner or later I run out of gas in the middle of the countryside. There had been a signal, I became aware of the need, but I undertook no actions to remedy the situation. I devoted all my energy to complaining and seeking a guilty party and someone on whom to vent my frustration

A scenario advocated by Nonviolent Communication: I’m still driving a modern-day car that has a fully functioning dashboard/control panel. The gas gauge shows that I’m on reserve. I identify my need: “Aha, I’m going to need fuel, but I don’t see a gas station right now. What am I to do?” I then take concrete and positive action. I will be alert to the next gas station I come across. I’ll go there and take care of my need. I provide the rescue service myself. Being aware of the need I have voiced, I awaken myself to the possibility of coming up with a solution. The solution does not occur immediately, but as I have become aware of the need, there is a much greater chance I will come up with a solution than if, as in the first scenario, I have no awareness.

If I sorted things out myself by filling up, this doesn’t mean I’m going to forgo my need for consideration or respect. Back home, I may say to my teenage child or spouse: “I’m disappointed at having had to fill up after you used the car (feeling—F). I have a need for consideration of my time and respect for having loaned you my car (need—N). In the future, would you agree to filling up the tank yourselves (request—R)?”

Indeed, we are often alienated from our feelings through our education or habit. This is even more so when it comes to our needs.

3. Needs (or values)

Most of us nowadays are to a large extent cut off from our feelings, and we are almost completely alienated from our needs.

I sometimes like to say that a concrete slab separates us from our needs. We have been taught to try to understand and meet the needs of others rather than listen to our own. Listening to oneself has long been synonymous with sin, or at least egocentricity or navel-gazing: “It is not right to listen to oneself like that. Oh, another person who listens to himself.” The very idea that we might “have needs” is still very often perceived as problematic.

Now it’s true that the word need has often been misunderstood. It does not mean a passing desire, a momentary impulse, a whim. We are referring here to our basic needs, the ones that:

Are required simply to maintain life.

We meet for the sake of balance

Relate to our most basic human values: identity, respect, understanding, responsibility, liberty, mutual aid.

The more I practice NVC principles, the more I’m aware of the extent to which better understanding our needs enables us to better understand our values. I will expand on this issue a bit later.

In a workshop I was running, a mother was complaining how she failed to understand her children. A state of war reigned in the household, and she said she was exhausted at “having to require them to do a thousand things that either they appeared not to understand or that made them feel like doing exactly the opposite.” When I asked her if she could identify her needs relating to this situation, she exploded and said:

“But it is not here on earth that we are meant to look after our needs! If everyone were to listen to their needs, war would break out all over. What you are offering is dreadful selfishness!”

“Are you angry (F) because you would like human beings to be attentive and listen to one another (N) in order together to come up with solutions to meet their needs?”

“Yes.”

“Is your wish (N) that there should be understanding and harmony among human beings?”

“But of course.”

“Well, you see, it’s difficult for me to believe that you will ever be able to listen properly to the needs of your children if you don’t begin by listening sufficiently to your own. It’s hard for me to believe that you will be able to understand them in all their diversity and contradictions if you don’t take the time to understand yourself and love yourself with all your multiple facets and your own contradictions. How do you feel when I say that to you?”

She was speechless, on the brink of tears. Then it was as if something clicked in her heart. The group stayed with her in silence, a moment of profound empathy. Then laughing, she observed: “It’s incredible. I’m just realizing that I never learned to listen to myself. So I don’t listen to them either. I just demand that they obey my rules! And of course they rebel. At their age, I rebelled too!”

Can we genuinely give proper listening attention to others without genuinely giving ourselves proper listening? Can we be available and compassionate toward others without being so toward ourselves? Can we love others with all their differences and their contradictions without first of all loving our own differences and contradictions?

If we cut ourselves off from our needs, there will be a price to pay—by ourselves and others.

If we cut ourselves off from our needs, there will be a price to pay—by ourselves and others. Alienation from our needs generates “invoices” in various ways. Here are the most frequent ways:

It is difficult for us to make choices that involve us personally. At work we usually manage to. But in our emotional, intimate lives, when it comes to more personal choices, how difficult it is! We hesitate, not knowing how to choose, hoping that eventually events or people will decide for us. Or we force the choice upon ourselves (“That’s more reasonable … That’s wiser”), helpless as we are to listen and understand our deeper yearnings.

We have an addiction: the way others see us. Unable to identify our true needs, those that are personally our own, we become dependent on the opinions of others: “What do you think about that? … What would you do if you were in my place?” Or, worse, we fit perfectly into the mold of their expectations, such as we imagine them to be, without checking them and simply adapting or over-adapting to them: “Whatever will they think of me? … I absolutely must do this or that … I must behave in such and such a way, otherwise …” We wear ourselves out being dependent on others’ recognition and, at worst, we become fad addicts (“Everyone does it like that … I’m going to behave like everyone else”). We become the playthings of various addictions (money, power, sex, television, gambling, alcohol, prescription drugs and other drugs, and now the Internet) or formal instructions (submitting to the authority of a demanding company, a directive political movement, or an authoritarian cult or sect). I have met many people suffering unconsciously or consciously from addictions recognized as such. In my view, the most widespread and the least recognized is the addiction to how we appear to others. We are not aware of our needs, and for good reason, since we weren’t taught to recognize them. We therefore expect our needs to be met through drugs, alcohol, people. We become dispossessed of—and disconnected from—our deepest and truest selves.

We have been taught to meet the needs of others, to be a good boy (or good girl), polite, kind, and courteous—the “good fellows,” as Guy Corneau calls them, listening to everyone except oneself.2 So, if one day, despite all that, we confusedly observe that our needs are not being met, then there is necessarily a guilty party, someone who has not bothered about us. We then get into the process of violence by aggression or projection referred to earlier, that is, a process where criticism, judgment, insults, and rebukes loom large. “I’m unhappy because my parents … I’m sad because my spouse … I’m feeling down because my boss … I’m depressed because of the economic situation or all the pollution … I’m in a bad mood because [name sports team] keeps losing …”

More often than not, we have experienced being subservient to the needs of others (or we have feared not being able to have our needs met) to such an extent that we bossily impose our needs on others—and no questions asked. “That’s how it is. Now, go and clean your room—and at once! … Do it because I said so, that’s why.” We then get into a process of violence through authority.

We are exhausted at trying to get our needs met and forever failing. Finally, we capitulate: “I give up! I give up on myself. I close in on myself, or I run away.” Here, the violence is directed against ourselves.

Yes, I hear you say, but what is the good of being aware of one’s needs if it means living in perpetual frustration? And doubtless you are thinking of persons who have indeed identified their needs for a sense of community or some sort of recognition and who haphazardly spend life seeking to belong and be recognized, going from cocktail parties to meetings, from sports clubs to humanitarian activities, never satisfied. Others, who so need to find their place, their identity, or their inner security, run to and fro from workshop to therapy, never finding real respite.

In the next chapter we will see how the very act of identifying our need, without it even being met, already produces relief and a surprising degree of well-being. In fact, when we are suffering, the first level of suffering is not knowing what we are suffering from. If only we could identify the inner cause of our discomfort, we would come through the confusion. Thus, if you do not feel well physically, if you have suspect stomach pains, headaches, or backaches, you get worried: “What is happening? Maybe it’s cancer, a tumor …” If you see your doctor and he identifies the cause, pointing out that you are suffering from indigestion, that your liver is overloaded, or that you have twisted your back, the pain does not go away. However, you feel reassured in the knowledge of what is happening, and you cut through the confusion. The same is true of need. Identifying it makes it possible to get out of the confusion that only adds to our misery.

A key reason for us to be interested in identifying needs is that as long as we’re unaware of our needs we don’t know how to meet them. We often then wait for others (parents, spouse, child) to come along and meet our needs spontaneously, guessing what would please us, whereas we ourselves find it difficult to name those needs.

A key reason for us to be interested in identifying needs is that as long as we’re unaware of our needs, we don’t know how to meet them.

Here are two examples of couples who came to me for consultations to sort out their relationship difficulties:

But first, notes on examples quoted

The examples from real life quoted in this book are deliberately abridged to avoid the length and detail of storytelling. I have endeavored to maintain the essence of the interaction because the exchanges took a lot longer than what appears here. Too, the time devoted to silence and inner work cannot be conveyed very well by the text, even though contemplative disciplines constitute a basic component of the work.

The tone or the vocabulary might at times seem naïve. I do this deliberately in many of my consultations in order to get to the heart of the matter, avoiding as much as possible any thinking or intellectualizing about what is truly at stake that might interfere with listening and inner awakening.

In an atmosphere of openness and profound mutual respect, the simplest words and tone often have the greatest impact. I have observed that simplicity sharpens consciousness, because attention, being required only a little or not at all for intellectual understanding, is available for emotional understanding.

People’s names have been changed, and sometimes roles have been reversed in order to respect confidentiality.

In the first example, a wife is complaining about her husband’s inability to understand:

“He doesn’t understand my needs.”

“Could you,” I suggested, “tell me a need of yours that you would like him to understand.”

“Oh, no! He’s my husband after all! It’s up to him to understand my needs!”

“Are you saying that you expect him to guess your needs, whereas you yourself find it difficult to determine them?”

“Precisely.”

“And have you been playing this guessing game for a long time?”

“We’ve been married for thirty years.”

“You must feel exhausted.”

(She bursts into tears.) “Oh, I am! I’m at the end of my rope.”

“Are you exhausted because you have a need for understanding and support on the part of your husband, and that is what you’ve been waiting for so long?”

“Yes, that’s exactly it.”

“Well, I fear you may wait a long time unless you clarify your needs for yourself and then tell him.”

Then, after a long, tear-filled silence, she said: “You’re right. I’m the one who is confused. You see, in my family, we were not allowed to have needs. I know nothing about my needs and, of course, I chide him for usually being wrong, without being able to tell him what I really want. Basically, I think he’s doing his best, but in the heat of the moment I seldom tell him that. And then of course he gets angry, and I sulk. It’s hell!”

With this couple, therefore, we did lengthy work on understanding and clarifying the needs of both. People who have always expected others to take care of them without doing much for themselves find it difficult to accept responsibility for themselves, and taking that initiative can be painful. However, it’s only through work on the relationship with oneself that the relationship with others may improve.

In the second example, the husband is the one doing the complaining.

“My wife doesn’t give me recognition!”

“Are you angry because you need to hear her express recognition?”

“Yes.”

“Could you tell me what you’d like her to say or do to express the recognition you need?”

“I don’t know.”

“Well, she doesn’t either! So it seems to me that you’re fervently expecting her to express recognition to you without you saying, in the most practical of terms, how you envision such recognition. It must be exhausting for her to sense on your part that there’s a strong request for recognition, yet faced with it, she feels helpless. I suppose the more recognition you ask of her without saying specifically what that means, the more she flees.”

“Yes, that’s exactly how it is!”

“Then I suppose you’re tired of this never-ending quest.”

“Actually, exhausted.”

“Exhausted because you want to share with her and feel close to her?”

“Yes.”

“Then I suggest you tell her how you would like to receive recognition, in concrete terms, and in relation to what.”

With this couple, we worked not on the need but on the practical request. This man felt wounded because he was not receiving the approval and recognition he wanted for the efforts he had made for years to provide the household with financial security, despite physical and professional circumstances of a trying nature. So he got stuck in complaining to his wife: “You fail to take the full measure of the efforts I’ve been making. You have no idea how hurtful that has been to me.” And she, shutting herself off from each criticism, was incapable of reaching him through all the bitterness. Finally, I suggested the following:

“Would you like to know if your wife has taken the full measure of the efforts you made and if she appreciated your profound commitment?”

“Yes, that’s exactly what I would like to ask her.”

“Well,” I turned to his wife, “you have heard that your husband would like recognition for his efforts. In more concrete terms, I would like to know if you’re aware of the efforts he has made and whether or not you appreciate them.”

“But of course I’m aware, and of course I appreciate them. I simply no longer know quite how to tell him. In the long run, I fear he can’t hear me. It’s true, I no longer respond, and I rush away to do something else.”

“Do you mean that, in your turn, you would like him to be able to hear that you’re not only aware of his efforts but also touched by them?”

“But of course, most touched, even moved, but he seems to be so hurt that he can no longer ‘recognize’ my appreciation.”

Turning to her husband, I asked, “How do you feel when you hear that your wife is touched, even moved, by your efforts?”

“Very moved, in my turn, and relieved. I’m becoming aware that I was actually obsessed with my complaining and feeling I was not receiving the recognition I was expecting, and I was no longer aware of the affirmations that in fact she gave me regularly. I myself am shut away in a cage.”

This awareness lightened the relationship and removed from it a weight that had, in effect, anesthetized the couple to the caring that each had for the other.

This second example makes two things clear: a)

a) As long as we fail to explain in concrete terms to the other party how we wish to see our need met, we might well see our request crushed under the weight of an insatiable need. It’s as if we were to have the other person carry the full responsibility for this need. Faced with a threat like that, the other person goes slightly berserk and says, “I cannot on my own assume responsibility for this huge need (love, recognition, listening, support, etc.), so I take flight or shut myself off” (in silence or sulking). This is precisely what Guy Corneau describes with these words: “Follow me, I flee; flee me, I follow you.”3 The husband is clearly desirous of recognition. The wife is just as desirous of escaping from the request. And the faster she takes to her heels, the more he chases after her.

Of course, this works in the other direction too. For example, a wife deeply wishes for tenderness and intimacy. Her husband panics when faced with such an expectation and seeks escape in work, sports, his papers. The farther away he goes, the more pressing her request. The more pressing her request, the farther away he moves. What he fears, perhaps even on a subconscious level, is having to meet a need for love unmet since childhood. That is too much for one man on his own. Were the situation reversed, it would be too much for a woman as well.

The lesson from this story: If needs aren’t followed by a concrete request in an identifiable time and space (e.g., need for recognition: “Would you agree to thank me for specific efforts I’ve been making for thirty years?” … need for intimacy and tenderness: “Would you agree to take me in your arms for ten minutes and gently rock me?”), it often looks to the other person like a threat. The other person wonders if he or she will have the capacity to survive such an expectation and remain themselves, maintain their identity, and not be swallowed up by the other person.

It’s worth remembering that we are often caught in the binary-thinking trap. Not knowing either how to listen to another’s need without ceasing listening to our own or how to listen to our own need without ceasing listening to the need of another, we often terminate the relationship. We cut off the listening primarily to protect ourselves. When I perceive listening to another’s need as a threat, I cut myself off from it and flee, or I take refuge in silence.

When I perceive listening to another’s need as a threat, I cut myself off from it and flee, or I take refuge in silence.

By expressing our practical request to the other party (e.g., “Would you agree to take me in your arms for ten minutes and gently rock me?”), we make the need less threatening (“I need love, tenderness, intimacy—help!”) because we “materialize” it into reality, into our day-today existence. This is no longer a virtual need, apparently insatiable and threatening. Rather, it’s a concrete request, well-defined in terms of space and time. In relation to a request like that, we are able to position ourselves and adopt a stance.

b)Another issue the above example clarifies is this: As we are obsessed by the idea of our need not being recognized, we aren’t open to observing that it is so. The wife had striven to recognize her husband’s efforts. Yet he was so caught up (or bogged down) in the notion of not being understood, that he couldn’t hear her. This is a common phenomenon. By dint of repeating to ourselves the thought that we aren’t being understood or recognized, that we are the subject of injustice or rejection, we give ourselves a new identity, to wit: “I am the one who is not understood, not recognized; I’m the one who is the subject of injustice or rejection.”

We get caught in the rut of this belief to such an extent that the outside world may well send us messages of warmth, understanding, and belonging—but in vain for we can’t hear them or see them. We will return to this matter in Chapter 3.

In these instances, it’s necessary to work on fundamental needs. The questions we may be asking ourselves, among others, are as follows:

Am I able to provide myself with the esteem, the recognition, the warmth, the understanding that I’m so fervently expecting others to give me?

Can I begin to nurture these needs myself rather than maintain myself in a dependent position regarding the approving opinions of others?

And above all:

Am I able to experience my identity other than in complaints and rebellion?

Am I able to feel safe and secure in ways other than leaning on something or someone, other than by justifying myself or objecting?

Am I able to feel my inner security, my inner strength of and by myself, outside the domain of power and tension?

Once we have identified our need, we are going to be able to make a concrete, negotiable request designed to meet it.

4. The Request (or concrete and negotiable action)

By formulating a request, or making a practical and negotiable proposal for action, we free ourselves from the third “concrete slab” that hampers us and prevents us from taking steps to meet our needs. By making a practical request, we release ourselves from the often intense expectation that another person should understand our need and accept the “duty” or challenge of meeting it. Such an expectation can last a long time and prove very frustrating.

Making a request means we assume responsibility for the management of our need and therefore assume responsibility for helping to meet it. Too often, though, we fall into the trap of mistaking our requests for fundamental needs.

The following example illustrates the distinction between a basic need, which forms an integral part of ourselves in most circumstances, and a practical request, which will vary according to circumstances.

The example of Terry and Andrea

During a workshop, I raise the issue of needs, stating that, in my view, human beings basically have the same needs. Doubtless they do not always express them in the same way, nor do they experience them in the same way at the same time. That is what lies behind marital, domestic, or school misunderstandings, the day-to-day battlefields of needs, not unlike wars waged with machine guns and missiles. To date, out of all of the behaviors I have observed, even the most frightening and the most appalling, I have been able to detect needs common to the whole of humankind.

Obviously, this is the basic hypothesis of my work, and it is based mainly on experience. In no way am I claiming to put forth a universal, comprehensive truth.

A participant, Terry, interrupted me and said: “I completely disagree with you. My wife and I do not have the same needs, and that has been the cause of so much tension that we’re on the verge of divorcing. We’ve come together to attend your workshop just to make sure we’ve done everything we can. We’ll be able to say to ourselves that we’ve left no stone unturned, but it’s without much conviction, especially when you start out by stating that basically human beings have the same needs.”

I suggested he come up with an actual situation where he got the impression that he did not have the same needs as his wife. This was his answer:

“Well, it happened a few months back. Things just exploded between us. You need to know that we both work outside the home, and we have three children. One weekend, the children had been invited to stay with their cousins. I came home on the Friday evening after work, tired and … whew (a long sigh), I really needed to go out to a restaurant with my wife. Do you think she did? Not in the least! She needed to stay at home and watch a movie. I then told her that she had no understanding at all about my needs, and she said it was exactly the same for her. We both flew into a rage, and in the end I went to bed in the children’s room. Since then, we continually have the impression that we do not share the same needs.”

“When you came home that evening, what feelings were alive in you?”

“Whew (another sigh). I was tired.”

“It looks like an unpleasant feeling to be experiencing at that time, and it shows that a need was not being met. Could you tell us what that need was?”

“That’s easy—a need for rest, of course. Hence the idea of going out to eat that evening. No meal to get ready; no washing to do!”

“So your feeling of fatigue shows a need for rest, for relaxation at that time. At the same time, I observe your sighing, a reference to your tiredness. You twice gave a long sigh. My impression is that the sigh is the expression of another feeling. What lies behind that sigh? If you go down a bit into your ‘well,’ what other feeling was with you then?”

Terry stopped for a moment to think.

“Well, I think that in addition to the fatigue of the week (it was Friday, and we had been on the run since Monday), there was an older tiredness. We have been running around for months—years—with work, the children, the house, and we don’t see much of each other.”

“A feeling of lassitude, being used up?”

“Yes, lassitude, deep lassitude, and a kind of listlessness.”

“And what unmet need did this unpleasant feeling point to?”

Once again Terry listened within. “I believe I just said it: My wife and I don’t see each other anymore. I need time to be with her, to connect. I need time for us to join with each other again and share intimacy.”

As Terry was expressing his needs, his wife, Andrea, sitting not very far from him in our circle, bursts into tears. “It’s crazy,” she said. “I had exactly the same need! I had gone to buy a prepared dish and a bottle of wine both of us like. I went to the video store to rent a movie we had never had the time to go see and, for once, the children were not at home. I was preparing for us to spend a happy little evening together as lovers, precisely to be able to get together for a few hours and share some intimacy!”

So what happened? What was it that occurred that led this couple, lucky enough to have the same need at the same time, to declare war on each other? Well, they mistook their requests for fundamental needs, and the needs became an obsession. Terry mistook his request to go out for a meal for a basic need, and Andrea did not listen. Andrea mistook her request to stay at home for a basic need, and Terry did not understand! Both Andrea and Terry stuck to their guns—and both were unconsciously trapped in their little cage! It wasn’t so much the wife failing to listen to the husband as the husband not having listened to himself before opening his mouth. It wasn’t so much the husband not understanding the wife as the wife not having taken the time to understand herself before opening her mouth.

I suggested re-enacting the scene. Terry and Andrea had had some practice and were aware that underlying their request, which was their present wishes, there was a basic need. If we listen to this basic need and understand it, we give ourselves the freedom to formulate a variety of requests to explore various wishes and to release ourselves from the trap into which the need/request confusion can plunge us.

To facilitate understanding of the example, I have again shown in parentheses the abbreviations for the components of the process: observation (O), feeling (F), need (N), request (R).

The role-play began.

“Darling,” Terry began, “this evening I’m tired (F). I just need to rest. I don’t feel like cooking or anything else (N), and I would like to know if you are in agreement for us to go out for a meal (R)?”

“Honey, I’m dead beat too. I’m happy (F) that we have the same need for rest (N). At the same time I feel sad (F) that we’ve both been so busy in recent times. I need to spend some quiet time with you, just the two of us (N), and I’m so afraid (F) that if we go out to dinner, we’ll be bothered by the waiter or distracted by friends. So I prefer to stay quietly at home. Everything is already on the table for the meal. We can dine, just the two of us, and then afterward, if you like, we can watch a movie I’ve rented that we haven’t had time to see yet (R).”

“You’re making me aware that I have the same need: to regain some lost intimacy with you, to spend the evening together, just the two of us, and that’s why I suggested going out for a meal this evening. At the same time, when I hear your proposal to stay at home, I feel a bit disappointed (F) because I also need a change of scenery, to get out of the house for once when the children aren’t here (N). So now that we have set out the criteria of what is at stake for us [formerly that would have been called a conflict!]—need for relaxation, need to get together, and have a change of scenery—what solution, what concrete action could we come up with to meet these varying needs?”

During that workshop, once Andrea and Terry had played out their exchange and deciphered it, they found that what would please both of them most that evening would be to go for a walk to the end of a lake in their area, taking a picnic basket with them and a little wine. In the old days when they were in love, they often went there, arm in arm. And then they got caught up by their working lives to such an extent that they forgot to even think about it. Yet this walk would have truly nurtured their need to get together, to relax, and to have a change of scenery!

This example sheds light on four main points:

We fall into the trap ourselves—and tend to drag the other person in too—when we don’t take care to differentiate our true need from our request. By seeing what underlies our request and identifying our need, we give ourselves freedom. We note, for example, that we can meet our need for intimacy and getting together with our spouse or our need for rest (restaurant, walk, movie) in all sorts of different ways. We escape from the fallacy that there is only one solution.

By taking care of our true need instead of haggling over our request, we together free ourselves from the trap, and we give ourselves a space to meet, a space to create! Andrea and Terry, harassed by the pace of their lives, had not taken time to get together or to be creative to make their evening truly satisfying. The solution they finally came up with, after looking at their needs together, proved much more innovative and satisfactory than any they had hastily come up with previously on their own.

By taking care of our true need instead of haggling over our request, we give ourselves a space to meet, a space to create!

In this spirit, it is useful to observe that we often skip to the “quickly done, poorly done” solution. For a long time I worked as a legal adviser to an American company where the expression “quick and dirty” was the common way of describing a quick solution to meet an emergency when there wasn’t enough time to look for the best solution.

Thus Terry, coming back tired from the office, decided on the quick-and-dirty solution to take his wife out for supper. Andrea, in the same way, coming back from her work completely drained, hurriedly buys a dish from the corner take-out and rents a video. Both of these initiatives of course have their value. However, it can be seen that neither he nor she really took the time to ask, “Deep down, how am I feeling this evening, and what would truly do me and my partner the most good? What would meet our real needs?”

This is one of the consequences of our education: seeking intellectually to solve things—and solve things fast!—using our intelligence, our performance capabilities, getting immediate results, moving as quickly as possible from seeing the problem to solving it without taking the time to listen to what is truly at stake.

Some time ago, I was emptying our dishwasher and putting away the utensils in a kitchen drawer. As I was closing the drawer, it stuck halfway. Bang! With a swing of the hip, I tried to close it by force. But it refused to budge, and I wound up with a painful hip, a damaged drawer, and a bent fork! Quick and dirty indeed. I was bowled over. What old “force to solve” pattern was alive in me? I thought I had released myself quite considerably from my own violence, but I still had some way to go when it came to acceptance and listening. Observing that the drawer is stuck, pulling it out, bending over, observing what is blocking the drawer, suggesting to the wayward fork that it lie down quietly among its kin, then simply closing the drawer … Thank you, fork, for having taught me to listen and accept before looking for a solution.

Since that time, I have truly believed ever more deeply that violence is a habit, an old reflex we can get rid of if we really want to. I’ll cover this in greater detail in the last chapter.

Our misunderstandings are often “mis-listenings,” themselves resulting from “mis-expressions,” “ill-spokens,” and “unspokens.” We are capable of learning to speak with sensitivity, force, and truth.

Remarks

Terry and Andrea as a couple were lucky enough to have the same need at the same time. This of course facilitated the negotiation of requests and the adoption of a common satisfactory solution. Having had the opportunity to clarify this misunderstanding in a way that finally pleased them, they went deeper into their training and found pleasure again in joining each other in the life they led together.

To be sure, not all disputes work out like that one. I can quote the example of spouses who had gotten to the stage of throwing plates at each other before they went to a training session together. After some practice they learned to listen to each other. It was even agreed between them that in their drawing room there would be two “nonviolent armchairs.” When a tiff occurred in the household, they would cry: “Stop! Armchairs!” As in a game of musical chairs where children chase each other, they placed themselves in a Nonviolent Communication zone where the instruction was “Here each takes turns to speak and to listen.”

After a while they observed that they didn’t operate at all at the same pace, that their respective needs were doubtless the same but seldom at the same time, and this made life together very difficult and, finally, unbearable. So they decided to split, to go arm in arm to see a lawyer and then the judge. They went as friends who loved and respected each other. One day after their divorce they told me they spent at least one evening a week together, and there they finally nurtured the friendship, the trust, and the transparency between them that they had always dreamed of. Such a relationship, however, had been impossible to achieve living under the same roof.

It’s often difficult to observe peacefully, with esteem and compassion, that we aren’t in agreement. Difference and therefore disagreement are frequently perceived as a threat.

We tend to be justly proud of our language and its wealth of nuances. However, verbal language represents but a tiny percentage of communication. Nonverbal language, according to the specialists, is thought to make up some 90 percent of our communication, while a mere 10 percent comprises verbal language! Being aware of that enables us to be attentive to our own body language (our tone of voice, our speed of delivery, our facial expressions, our body positions), as well as the body language of other people. To become aware of this, note the impact, the power of a single reproachful look or, on the other hand, a look of approval coming from someone close (parent, spouse, child, hierarchical superior, teacher).

In secondary school, we had a Latin and French teacher we liked very much, particularly on account of his humor and volubility. When he would tell us, once a month, that he would start the first lesson in the afternoon ten minutes late because he had a meeting, each time he told us mischievously, “And when I do come, I’ll be listening to hear nothing!” We loved the way he used words; he stimulated our young grey matter and made us appreciate the finer points of language. Returning from his meeting (we carefully respected his instructions, out of affection and respect for him), he came in from the back of the classroom and went right up to the blackboard without a word. He looked us up and down approvingly, one hand cupped behind his ear to show he was listening and hearing not a sound, the other hand showing with thumb and index joined that he appreciated the quality of the silence we had respected. When he reached his desk he started teaching at once. We had no need for any other sign of recognition for our efforts to be silent. Although I was highly amused by each of these little rituals, I was astounded at the strength and sobriety of his presence alone, where not a word was spoken. Nor did it need to be.