CHAPTER 3

Becoming Aware of What Others Are Truly Experiencing

If you only half say it, only half of it will be understood.

ANONYMOUS

Communicating Is Expressing and Receiving Messages

Saying it all, listening to it all

Every day I see that, for a host of people, communicating means managing to express oneself and allowing others to express themselves. And after both sides have had opportunity for expression, the belief is that there has been communication. How many of these people, however, complain about relational difficulties and say: “But my husband and I, or my children and I, communicate so much. We tell each other everything; I don’t understand why we don’t get along better”?

They say everything! Yes, but do they listen to everything?

The key often lies here: We fail to hear because we fail to listen. The title of a book by Jacques Salomé, If Only I’d Listen to Myself,10 is eloquent in this respect. Although we may often have learned to express ourselves, if only a little, at school or by observing others, seldom has anyone learned to listen, to listen without doing anything, without saying anything.

It is no easy matter. People come to me and say, “I communicate quite well with my husband, my children …” But they don’t easily accept that they’re very much at ease when it comes to saying everything—for saying what is in their hearts, preaching to other people, or giving them advice—but less at ease, or even incapable, of hearing things, simply listening to what another holds in their heart. They are less capable of examining the feelings and needs underlying the words, and then, in their turn, expressing the feelings and needs (without judgments) that are alive in them.

Talking true, listening true

Just listen to typical table, society, work, or reception conversations. Seldom do we listen truly. Rather, we politely wait for our turn to take the floor while preparing our own bit—at best focusing only haphazardly on what the others are saying and at worst using their comments essentially as a springboard for our own opinions. Sadly, most of these “conversations” are little more than sequences of monologues. There is precious little encounter, and that explains why there are so few nourishing, stimulating, energizing conversations. We don’t talk true, nor do we listen true. We pass each other by. We miss each other.

More and more, I’m of the belief that in this “passing by” lies the basic emptiness from which most of us suffer so acutely. We’re missing out on the nurturing presence that is born of true connection. And we’re missing out on the connection both to ourselves and others.

As long as we don’t know what we’re looking for, we try to fill the void with all sorts of tricks: We get a high out of work, amorous conquests, hyperactivity; we get giddy with consuming, possessing, seducing; we drive ourselves silly with alcohol, drugs (whether prescription or otherwise), sex, or gambling; we hide behind a screen called responsibility, duty, concepts, and ideas. Sometimes we desperately wait for a miracle breakthrough from a therapy workshop, a trip to the other end of the world, or a spiritual experience, before discovering, like Paulo Coelho’s alchemist, that we are sitting on our treasure, that our treasure is at the heart of the connection to ourselves, in ourselves, and with others.11 U.S. essayist and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson put it this way: “What lies behind us and what lies ahead of us are tiny matters compared to what lies within us.” Indeed, there is no other form of possession, no other power to hold, no inebriation to enjoy, no marvel to contemplate other than connection. Connection brings us to ourselves, to others, and to the world, so that we are neither excluded nor separated from anything unless by our own divisive thoughts.

The entire universe is moving and connecting—creative force itself.

As long as we live a polarizing binary consciousness (I leave you to be with me; I leave me to be with you), we shall experience separation, division, and therefore emptiness. It is by working the extra consciousness, unified consciousness, that we shall be more and more able to get a taste of unity through diversity, joining universality out of individuality.

Let us come back to feelings. In the way you use feelings, I urge you to be especially alert to your intentions, your motives. What is my intention, my motivation? To cleverly induce another person to do what I want or to move compassionately toward another? Beware of emotional manipulation!

Indeed, another old and unfortunate habit has gotten us into the habit of frequently using feelings to control others or exercise power over them. For example: “I’m sad when you get bad marks at school … I’m angry when you don’t keep your room clean … I’m disappointed when I see your report card.” Or, “better” yet: “You disappoint me greatly … You make me completely give up … You exhaust me.”

This way of acting provides minimal information about our needs and brings the full weight of our feelings onto the shoulders of another; another person becomes responsible for our state, and we make them pay the price. We allow our well-being to become virtually dependent on them, and we intend to make them aware of their responsibility for our well-being, also expecting them to feel guilty for our misery.

Acting this way, we assume less responsibility for what we are experiencing and give away to another disproportionate power to determine our happiness or our unhappiness. We give others the remote control for our well-being. They zap, and we skip from mood to mood at their whim.

An exchange between mother and child

Conventional version

“I am sad when you don’t clean up your things.” For the mother, that means:

“If the child tidies things up, I’m happy.”

“If the child doesn’t clean up, I stay sad.”

I therefore give another the power to keep me sad or keep me happy but not the freedom to do something else or to do something differently. In other words, I maintain an emotional power game, a trial by strength, where there isn’t real freedom.

As for the child, unless she understands and at that time shares the same need for order as her mother, she can only say to herself: “Oh, Lord! Mother is sad, so I’m going to be in for a rough ride if this goes on. I want her to be happy, so I’ll do as she says even if I don’t understand the reasons, even if I don’t agree with the reasons, even if it is done unwillingly.” At the end of this repeated conditioning, the child learns to adapt, even over-adapt, to the desire of others, ignoring herself.

Or the child may say to herself: “It has nothing to do with me. I do what I want to do, and I will never clean things up if I’m ordered to do so.” And at the end of this repeated conditioning, the child learns systematic rebellion, automatically contesting everything she is asked to do.

Nonviolent version

“When I see your exercise books on the table and your clothes on the floor (neutral observation to show the other person, without any judging, what I’m talking about), I feel upset (F) because I need help in setting the table for the meal (N). I would like to know if you would agree to put them away (concrete, negotiable R).”

The mother is annoyed because she has a need that isn’t being met; she isn’t annoyed because of her child. She expresses this need to her daughter and thus gives her a sense of her annoyance without accusing the girl, then she makes a negotiable request that allows her daughter complete freedom.

As for the child, she has the opportunity or the freedom to position herself in relation to the need expressed and may say:

“Yes, I agree to put them away.”

“No, I don’t agree because I don’t want to put them away—or maybe I’ll do it later. Why don’t you talk to my brother? He’s a lot messier than I am.”

Perhaps you have doubts about the efficacy of such an exchange, and you say to yourself for example: “Oh, my goodness! With my child that would be impossible. If I don’t demand something, I get nothing.” If that is so, check inside regarding:

Your feeling. Are you not tired with this situation?

Your need. Is it not a pleasure for you to share your values (order, for example) and your needs without systematically stirring up resistance or having to compel the other person?

If you can identify with the fatigue or the need, rejoice! You are reading the right book. Sharing, transmitting, and exchanging our values without submitting or making another submit is one of the advantages of practicing the method I am presenting to you here.

Obeying and taking responsibility are not the same thing.

By naming the need, on the one hand, we shed light on our own clarity and assume full responsibility for what we are experiencing; on the other hand, we inform others of what is alive in us and, at the same time, respect their freedom and their responsibility. We invite them to take responsibility and not simply to obey. We invite them to get connected to themselves while staying connected to us.

When noticing how carefully I had stressed the importance of expressing true feelings, identifying our own needs, and expressing them to others in the form of a non-compelling request, a workshop participant once told me the following story …

“In fact, I used to believe that I had trained myself through my readings and discussions in nondirective language and the ‘I’ form. I believed, therefore, that I had learned to speak about myself simply because I said ‘I’ rather than ‘you.’ However, the ‘I’ allowed me, with no compunction, to chuck my rubbish bin of frustrations in the face of others. I would scream at my husband: ‘I’m exhausted because you don’t do anything for the children … I’m at the end of my rope because you give me no help … I’m fed up because you’re away so often.’

“And he would reply (because he had read the same books as I), ‘But honey, use the ‘I’ form, talk to me about you, about what you feel, about what you want.’

“Then I would answer, ‘Well, that’s what I am doing; I’m telling you that I think you are away too often, that you should help me more, and that it’s time things changed.’

“And he would answer: ‘But I do help you sometimes, and then with my work I don’t have any choice. You just keep complaining.’

“In this exchange (one could hardly call it a dialogue because I was complaining; he was arguing and contradicting me) we were not trying to get closer to each other. We were both trying very hard to bring our spouse around to our point of view. I can now see the importance of expressing the feeling and the need together because that clarifies things and increases personal responsibility.”

An exchange between father and child

Conventional version

“I am very disappointed with you when I see the school results you got this month. If you go on like that, your year is going to be charming indeed! And then you won’t be ready to find a job later. Look at your sister; she is much more conscientious.”

I use the feeling here to make the other person react out of fear, guilt, or shame. Now reread this version as if you were the child, and check for yourself the state of mind you are in, the taste for life you have after what you heard your father speak that way.

Nonviolent version

“When I see your school results this month, and especially a D in math and an F in statistics (an observation that is both neutral and detailed, to express to the other person what I am reacting to), I feel worried and concerned (F). I need to be reassured about two things, namely that you:

Understand the significance of these subjects and know how they will be useful in the future.

Feel OK and welcome in your classroom with your teacher, so that if you do run into difficulties, you will feel at ease about saying so (F). Would you agree to tell me how you feel in relation to all that (R)?”

Once again, ask yourself how, if you were a child, you would feel if your father spoke to you that way. What energy, what taste for life would be alive in you?

When I do this exercise with children, the reaction is immediate. In the first version they have the impression of being judged, misunderstood, rejected. To get out of the discomfort caused by these feelings, either they sulk and argue (“It’s the teacher’s and the school’s fault … I’m hopeless … A buddy took my notes”) or they feign indifference (“I don’t care; it’s not important—just a minor test, no problem at all”) or they clearly demonstrate their distress over the meaning of things (“In any case, school is a waste of time since we’re going to wind up unemployed in the end”).

In the second version, the children feel considered and realize their feelings and thoughts count. They are made to feel welcome with their difficulties and the progress they may have made. The desire of the parents to understand without judging touches them. The proposal to speak freely (without fear of any compulsion, any expectation to face up to, any result to achieve) allows the leeway to express themselves freely. In the next two sections, “Communicating is also to give meaning” and “Listening without judging,” I will suggest observing and analyzing the reactions of two young people, John and Isabel, after hearing the second version of the parent/child exchange.

Communicating is also to give meaning

Here is the reaction of John, a fourteen-year-old student:

“Well, I’d like to say to my parents that I don’t give a hoot about math. I’d like them to tell me why I have to study that subject. They always say back to me, ‘Because it’s in the curriculum’ or ‘Because that’s the way it is’ or maybe ‘You don’t always do what you want to do in life.’ But I need to talk about it and find out why.”

“Are you saying you have a need to understand the meaning of what you’re doing, and if you don’t understand the meaning of it, then you don’t want to do it, or you do it badly?”

“Well, yeah … right. If I don’t see the meaning of it, I need someone to explain.”

Remarks

For me, this is the number-one property of communication: providing meaning for what I do or what I want. In previous generations—and certainly in mine—one might have heard: “That’s the way it is because that’s the way it is … Stop asking questions … Do it because I said so … You’ll understand later … There are things you have to do in life whether you like it or not.”

Not to mention, of course, the tragic “It’s for your own good,” which has done so much damage and to which psychoanalyst Alice Miller devoted a well-known book.12 The book For Your Own Good: Hidden Cruelty in Child-Rearing and the Roots of Violence taught me a great deal about the subtle mechanisms that generate violence from infancy, in a way that is all the more insidious as it is dressed up in good intentions. Fortunately, this attitude is on the wane. Many in today’s young generations are calling for meaning and are refusing things that don’t have meaning in their eyes.

Sooner or later each of us will be called upon to review how we define our life and our priorities—and deal with issues surrounding meaning.

The situation is relatively new, at least on a broad scale. Millions of young people are taking on the previous generation about meaning and are refusing to obey and blindly follow instructions, habits, automatic reflexes. It could be argued that this phenomenon already took place in much of the world in the 1960s and 1970s, but the trend appears to be even stronger today, enhanced in no small measure by global mass communications. I see here a fabulous opportunity for human beings to become more responsible for their acts because they’re more aware of why they are acting. Naturally, this is a transformation that cannot occur without conflict and without pain. Imagine yourself a parent or merely an adult (whether or not you fit one or both descriptions). Are you generally clear about the meaning of what you are doing? Can you usually name and explain the value or the need that is guiding you in your behaviors overall? Sooner or later each of us will be called upon to review how we define our life and our priorities—and deal with issues surrounding meaning. The present cause of discomfort among many parents and school staff has much to do with their being urged by young people, directly or indirectly, to reassess their priorities and redefine the meaning of their acts and their life. The following story illustrates this:

A father, a businessman, told me how his twelve-year-old son asked him why he worked ten hours a day and why he never seemed to be at home.

“To earn a living,” replied the father.

“Yes, but why?” continued the child.

“For our security and comfort,” said the father.

“If it’s for my security and my comfort, I’d rather you came to get me from school at four o’clock and we go and do sports together.”

Here is a father who reassessed his priorities and, after consulting with his son, agreed that once a week they would go and be involved in sports after school.

So you see how life invites us to change and renew ourselves.

Listening Without Judging

Here is the reaction of Isabel, a fifteen-year-old schoolgirl:

“Uh, there’s something I’d like to talk to my parents about, and if they would bring it up with me, I’d feel more comfortable talking about it.”

“Can you tell what it’s about?”

“Well, I feel awful in my class. Because of my schedule, I’m the only one to go to math class with a bunch of kids who know one another already. It’s hard for me to fit in and feel comfortable when it comes to asking questions that are bothering me. As soon as I say I don’t understand, everyone laughs and makes fun of me. So I don’t say anything anymore and don’t ask any more questions.”

“Do you feel alone (F) in this situation, and you would like to be made welcome and understood by the other pupils (N)?”

“Yes, that’s right.”

“And would you like to talk about that with your parents as well so they can understand and perhaps support you (N)?”

“Yes, but they don’t believe me. They think I’m not studying, that this is just an excuse. They tell me just to try harder.”

“So do you feel disappointed and perhaps annoyed (F) because you really have a need for them to understand that it’s not so much a question of studying but of atmosphere in the class (N)?”

“Right.”

“You perhaps also feel tired after all the efforts you’ve made (F), and maybe you just want to have consideration for the effort you’re making.”

“Yes (tears in her eyes). In fact, I’m just asking them to listen to me, for me to be able to express what I’m experiencing. I don’t really want them to help or do anything. I want them to listen to me without judging me.”

I very often hear a simple need like that: to be listened to without being judged. Why is it so difficult for parents to listen to their teenagers? Mostly I observe that it’s because the parents believe they have to do something, act, perform, get a result, a solution and, if possible, immediately. Yet a solution may elude them, and they may feel helpless, or perhaps they’re fed up with trying to come up with solutions. Consequently, to escape the tension brought about by the helplessness, the fear, or the fatigue, they’ll go for flight, denying the problem (“Oh, but it’s not so serious … What a drama you’re making of it all … You could at least try … Life isn’t always easy”)—or for aggression (“It’s your fault; you don’t study enough … If only you’d look over your lessons more”) rather than simply taking the time to connect with their children and listen to them genuinely.

It is worth noting that a young person can take on similar attitudes: aggression (“My parents just don’t get it … They’re such numbskulls … I’m so fed up”) or flight (“I don’t tell them anything anymore … I just secretly leave”), failing to make a true connection. Fortunately, listening can be learned.

Communicating means expressing and listening.

Indeed, communicating means expressing and listening; it means expressing oneself and allowing another to express also, listening to oneself, listening to the other person, and often checking to make sure the reciprocal listening is of good quality. Many relational difficulties stem from the fact that we don’t take the trouble to ensure that we have properly heard another person and that the other person has heard us correctly. Repeating or reformulating, if need be, what the person has said will make it possible for us to check if we have properly understood. Similarly, inviting another person to repeat or reformulate what we have said will often enable us to check whether we have been accurately understood.

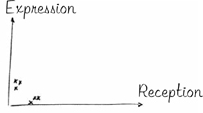

If we were to represent communication between human beings on a diagram, we could draw one like this:

The exchange of a message, therefore, comprises two aspects: expression and reception. We have learned to be good boys and good girls—not to make too much noise, not to bother people, not to occupy too great a space, not to “bother others with our little problems.” So we do of course express ourselves a little, but not too much, so as not to be subject to criticism, so as not to make ourselves vulnerable, so as not to show to what extent we are sensitive, even delicate. On the diagram, we are down on the left.

Since we have learned to listen properly to everybody else’s needs except our own—and to act as a St. Bernard dog and meet everyone’s needs except our own—when it comes to listening to another and receiving their messages, our tendency will be to think “I don’t mind listening to you a little, but not too much because it’s going to start getting on my nerves if I keep on listening to other people all the time. I have other more important things to do.” On the diagram, our ability to receive another’s message will often be located in the bottom left as well.

There also are extremes. From time to time, we get fed up with trying to listen to others, and we try to impose upon them our vision. We express ourselves completely, but we switch off the “receive” button. We start acting like tyrants, despots. We impose our need without listening to the other person’s need. We adopt an attitude of authority, power over others, control.

On the diagram, it will look like this:

At other times, we are perhaps so exhausted at having attempted in vain to get our needs recognized, to have expressed them without getting any form of recognition or consideration, we give up. We submit to the behavior of the other person and no longer react. We just give up.

In extreme cases, we act like slaves, victims. Our attitude is one of submission, resignation.

On the graph, it looks like this:

NOTE: We can be one thing at one time, another thing at other times—a tyrant at home, a slave at work, or the reverse (or a little of both, tyrant and victim, depending on the time of day and the circumstances). Within a single moment, within a single sentence, we can be both tyrannical and victimized: “Go and clean up your room immediately—and no discussion about it. Oh, my God! What have I done to deserve children like that?”

Tyrant, victim—or both?!

We can, therefore, go from one extreme to the other at regular intervals, and most of the time we wallow in an area of mistrust, which may be represented as follows:

As long as we operate in this area, we’re afraid to express ourselves, to reveal ourselves, to show others who we are, with our fortunes and misfortunes, our contradictions, our weaknesses, our vulnerabilities, our fear of developing our talents, our identity, our creativity, our fantasies, our multiplicity. We wear a mask to conceal most of that, to protect ourselves from others’ eyes.

Similarly, we are afraid to listen to another person, to hear their stories and their difficulties. We shut ourselves off or reduce to a minimum our ability to listen and take in because another’s difference or suffering makes us feel insecure or fragile and gives us the impression that we’re going to have to stop being ourselves or we’ll have to meet some outside expectations, a design someone else may have for us.

Relinquishing fear and moving to trust

Personally, I’m struck to see to what extent fear has for so long been at the heart of most of my relationships with human beings:

Fear of what others may think or not think

Fear of what they may say or not say

Fear of too many words, fear of too long a silence

Fear of lacking love, fear of being overwhelmed by love

Fear to speak, fear not to speak

Fear of having nothing to do, fear of being overloaded

Fear of pleasing, fear of displeasing

Fear of seducing or being seduced …

My word! What a bunch of fears. And think of the energy that goes into fighting those fears!

It took me a long time to realize that all of this energy “eaten up” by fear was then no longer available to act, to create, to quite simply be. Paralyzed to a greater or lesser extent by fear, I pretty much stopped evolving and, consequently, I stopped being. It was as if I was coagulated in the slough of my fear—stuck, identifying with my fears most of the time, having only momentary flights of confidence and creativity.

I remember very precisely the analysis session during which this way of “functioning” (if one can use a word like that for such a dysfunctional way of living!) exploded in my face. All of these little fears, side by side, heaped up one atop the other over the years, suddenly appeared to me like a crawling cancer. I had explored them one by one, nicely, for years of analysis: “I’m afraid of this. I’m worried about that. I’m concerned by such and such.” Examined separately, they looked benign, harmless, coincidental.

In a flash, though, with a breakthrough of consciousness into the fog of the subconscious, through therapy, I was able suddenly to see them as a single whole, like a teeming entity, a web-like network. I appreciated in an instant the extent to which they were neither coincidental nor occasional but structural, that is, representing the way I truly operated. At that moment, I became aware that I was in danger of dying. Perhaps not dying an immediate physical death, but in danger of psychic death, in danger of becoming what Marshall Rosenberg calls “a nice dead person, smiling and polite but dead inside, dead scared.” This awareness awakened my instinct for survival; it was a matter of urgency to change. It was essential to relinquish fear and swing over to trust.

Tired of fear, I wanted to try trust. It was new. Trust was unknown and therefore produced … fear. Too bad, I had had enough! I put my money on trust; I was counting on it. I calmed my myriad inner voices, which were kicking up a fuss and protesting: “Watch out! Things will go wrong! Be careful!” I repeated to myself: “Trust. What do you have to lose? Fear, the main alternative, certainly wasn’t satisfactory. At worst, trust won’t be satisfactory either. But, hey, there’s nothing to lose.” In my present paralyzed way of life, I would die of boredom anyway.

This is one of the challenges of life: either staying in the known—which weighs upon us or even tortures us, but which is reassuring because it is known, as familiar as an old coat or an old pair of jeans—or swinging over into the unknown, which can be infinitely more joyful, infinitely richer, but (and here’s the kicker) it involves a passage, a change.

Ah, changing! Stopping doing the same thing, saying the same thing, thinking the same thing … in order to do something new, say something new, think in a new way, pray in a new way!

If I don’t change, I die; if I don’t renew myself, I die. French author Christian Bobin expresses this fear of the unknown thus:

“Two words give you a fever. Two words nail you to your bed: change life. That is the aim. It is clear, simple. But we can’t see the path leading to the goal. Disease is the absence of a path, the uncertainty of routes. We are not faced with a question. We are inside. We are the question. A new life, that is what we would like, but willpower, part of the old life, has no strength. We are like these children, holding a marble in their left hand and not letting it go until they are sure that the swap is in their right hand: we would like to have a new life but without losing the former life. We refuse the moment of passage, the moment of the empty hand.”13

As soon as I decided to quiet my fears and swing over to trust, my entire energy field changed. More precisely, the energy I had previously been devoting to fighting my fears and attempting to manage them could now be engaged in change, in openness to novelty. And, within a few years, my professional life and my emotional life changed radically in ways that were fulfilling beyond all my hopes and expectations. In two or three years, my life evolved more than in the previous thirty-five.

I often get the feeling that one sometimes has when sailing. After a long time of sluggishness, with the water lapping against the boat and the boat turning around on itself, its sails flapping, there’s a stomach-churning moment, then the wind picks up and fills the sails, the boat heels over, finds its heading, and sets off toward the open water. It is that euphoric feeling of being carried away, joyfully forward, that is most often alive in me these days.

Although I have observed and experienced my own mistrust, I observe it just as much in people I work with. Whether at workshops with groups or in individual sessions, my observation is that the feeling dominating much of human experience is an uncomfortable mixture of fear and mistrust.

Do I act out of the joy of loving or out of the fear of not being loved?

Even for couples, where the dream might be all trust, emotional security, a letting-go in love, oh, what fears! What doubts! “If I do this, what will he believe or say? If I undertake to do this, what will she think? I must do this or that; otherwise they will be sad, angry, disappointed, etc.” So many behaviors are guided not by the joy of loving but by the fear of no longer being loved, not out of the joy of giving but out of the fear of not receiving in return. I buy love, I buy belonging. It isn’t a generous exchange of love in a spirit of abundance; it’s more in the spirit of a subsistence economy.

Many live in relationships governed by projection and dependence: “I cannot live alone; you cannot live alone. If you go, I die; you die if I go. I lean on you; you are the father (or mother) I didn’t have. I am the child you need to smother with all the care you yourself did not receive. I expect you to protect me and reassure me eternally; you expect to be able to comfort me eternally. Together, we attempt to fill up our gaps and voids, insatiably.”

It seems to me that very few people living as couples are truly in a person-to-person relationship, a relationship of responsibility, autonomy, and freedom where each party feels the strength and confidence to say, “I am capable of living and finding joy without you; you are capable of living and finding joy without me. We, you and I, both have this strength and autonomy, and at the same time we love being together because it’s even more joyful to share, to exchange, and be together. We don’t strive to fill up the gaps, but to exchange plenitude!” Sometimes this state of being is called synergism—where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Also evoked here are “pearls” of wisdom from Gestalt co-founder Fritz Perls of Germany who wrote:

I do my thing, and you do your thing.

I am not in this world to live up to your expectations,

And you are not in this world to live up to mine.

You are you, and I am I.

And if perchance we find each other,

It’s beautiful.

If not, it can’t be helped.

The practice of Nonviolent Communication also is an invitation to live confidently and to enter confidently into relationships. It urges us to find sufficient inner security and solidity, confidence and self-esteem to dare to take our place without fear of trespassing onto someone else’s space, confident that there’s room for everyone—to dare to say what we want to say, to be who we want to be, without fear of being criticized, made fun of, rejected, or abandoned. It therefore makes it possible for us to dare to maximize self-expression and self-actualization.

In the same way, by helping us find greater inner security and solidity, in better nurturing our self-confidence and our self-esteem, Nonviolent Communication encourages us to listen to others as completely as possible, to dare to welcome them in their complexity or their distress, without assuming we are responsible for what is happening to them. Nor must we “do something” other than listen and attempt to understand. Nonviolent Communication urges us to love others’ taking their place without fearing that they’re trespassing on ours, confident that we can set our own boundaries and that there is room for everyone.

On our diagram, this quality of presence—with oneself and presence with others, with oneself listening and expressing, and with others listening and expressing—may be represented like this: maximization of expression and reception shown by a cross in the top right-hand corner of the diagram, the area of trust.

We strive, therefore, to maximize our ability to express what we feel, what needs we have, and to maximize our ability to receive the feelings and needs of others.

We thus live increasingly in a climate of trust, trust that we can be in the world without fearing “bothering” other people and that others can be in the world without fearing our being “bothered” by them.

You can see that I have marked an arrow between the mistrust area and the trust area. This arrow does not go in a straight line. It represents the path we are invited to set out on—as long as we really want to—to evolve from the mistrust area to the trust area.

Walking quietly toward a fountain

An image that for me is an illustration of this path is one I found in The Little Prince by Saint-Exupéry, a book that has never lost any of its freshness. Remember, the Little Prince travels from planet to planet. One time, he meets a tradesman who has found a pill to make it possible never ever to be thirsty again. And the merchant is so proud that he boasts the qualities of his pill, saying, “Thanks to this pill, you will no longer have to go and draw water from a well or drink at a fountain. I have calculated that it will be possible to save fifty-three minutes a week!” When the Little Prince hears that, he is dismayed and answers, “If it were me, if I had fifty-three minutes, I would walk very slowly toward a fountain.”14

In other words, I would take the time to go very slowly toward anything that quenches my thirst, that which revitalizes me. I would rejoice at the freshness of the water even before tasting it. I would refresh myself with its melody even before having wet my hands. I would take the time to be wherever life nurtures me, truly quenching my thirst.

We live in an era, however, when we are communicating ever more quickly and ever more poorly. We have cell phones, answering machines, e-mail, information highways, and so on. We exchange huge volumes of information. Yes indeed, but do we connect? Do we have nurturing connections, satisfying ones?

We often use pills so as not to be thirsty. I worked for a business where a woman, a mother in an executive job, telephoned her son regularly around seven in the evening: “Darling, Mommy has a lot of work to do, and tonight she has another meeting. She’ll come back later. There’s a great pizza for you in the freezer. Put it in the microwave for five minutes, and you’ll have a good meal.” Pill! In other words: “I don’t have time for you, sweetie, so the pizza will be a substitute for a family dinner.”

Or: “Darling, Daddy has to leave this afternoon for an important meeting. There are two DVDs in the TV cabinet. Have a good time. Kisses, and see you tonight.” Pill! I don’t have time for you, darling. My golf game, my tennis match, or my meeting is more important. Watch the movies. That will be a substitute for a family evening together!

Or, more subtle yet: “Darling, I understand how very unhappy you are. Sleep well tonight, and all will be better tomorrow.” Pill! You know, listening to you tires me and bothers me. I have other things to do, and in any case it’s late and I’m tired. This piece of advice will be a substitute for understanding.

And we race on and on, from thing to do to thing to do, from pill to pill, and then we are surprised to be insatiably thirsty on our way, on a quest, ever dissatisfied, our throats and hearts dry! Not to mention our children and spouse … Without knowing it, we’re sitting next to the only well that could truly quench our thirst. It’s called presence with self, presence with others, presence with the world, presence with divinity.

Taking the time to understand one another

During a training session, a mother screamed at me: “That’s all well and good, but we don’t have time to listen to one another like that. You just don’t know, for example, the race it is in the morning for everyone to be on time to school and for me to get to work! Look, every morning for weeks, around 7:45, just when the two oldest children already have gotten into the car, with their backpacks on their laps, to be at school by 8:15, and I still have to drop off my smallest daughter so I can be at work by 8:30 … do you know what the little one is doing? She’s combing her hair in leisurely fashion, looking at herself in the bathroom mirror! Do you think I have time to say to her how I feel and what my needs are? I just explode and call her a selfish airhead and drag her off to the car.”

“And how do you feel then?”

“Furious. We waste time every day. The boys nearly always arrive late at school, and I’m late too. And besides, everyone grumbles for the whole journey.”

“And you say this has been going on for weeks?”

“Yes, every morning. So surely you can see that we don’t have time to discuss things as you’re suggesting!”

I proposed that she herself play the role of her daughter, and I would take her own role. Experience has shown that when we put ourselves into another’s shoes, that often allows “pennies to drop” and awareness to be enhanced. She threw herself into the part of her daughter, who was doing her hair in carefree style in front of the bathroom mirror.

“Daughter, when I see you doing your hair now (O), I really feel worried (F) because I’d like the boys to be on time to school, and I’d like to get to the office on time too (N). Would you be willing to come with us now (R)?”

(Silence.) The mother, playing her daughter, continued to do her hair, unperturbed.

As for me, in the role of the mother, realizing that talking about myself would be of no use at that time, I chose to speak about her and to attempt to connect with her. I then voiced the feeling and the need I imagined she may have had, because they were the ones apparent in me if I put myself in the shoes of the daughter who was choosing calmly to do her hair at this time of the day when everyone in the household was getting hot and bothered: “Daughter, are you sad (F) about something? Is there something you would like me to understand (N) that I don’t always understand?”

“You’re mean!”

“Are you sad (F) because you aren’t reassured about my loving you as much as you would like (N)?”

“You don’t wake me up in the morning anymore!”

As soon as those words came out, the mother stopped the role-play and blurted: “That’s it! I’ve got it! For several weeks now I haven’t been going up to give my daughter a special hug in her bedroom to wake her up in the morning. I always used to do that before waking up the boys with a ‘Morning, boys. It’s time.’ Waking up was different for the boys and for her. Now I go along the passage and ring out a single ‘Morning, children. It’s time.’ And I no longer give her a hug. In fact, she’s perhaps sad to be put on an equal footing with the older children and to lose her special status as the youngest child.”

The workshop was spread over two days at a week’s interval. So the woman had an opportunity to practice at home. She came back the next week and said, “That was it! The next morning when my daughter was once again taking her time to do her hair at 7:45, I decided we would perhaps all be late today, but that we were going to settle this matter once and for all. I sat beside her calmly in the bathroom and said to her: ‘Tell me, are you sad because I no longer come and give you a big hug every morning?’

‘Yes, you don’t love me anymore. You love the boys more than me.’

‘Are you disappointed because you’d like to be sure that you’re still my darling little girl and that I won’t force you to do the same things as the boys just because you’re growing up?’

‘Yes.’

‘What can I do to reassure you that I love you very specially and that you can grow up at your own pace?’

‘You can give me hugs again in the morning!’”

Thus, the mother resumed the ritual of the morning hug. Naturally, that day everyone arrived a few minutes late, but the younger daughter no longer had any need to hold everyone up every day to remind them that she existed and mattered.

Curiously, we often have time to argue every day for weeks but not the time to connect for just a few minutes! What are we truly focusing on? Logistics (being on time) or the quality of our connections (being on time willingly)?

When I see to what extent our misunderstandings can often be clarified in short order through reciprocal listening, I’m more and more surprised to observe the tragic old habit of considering that “arguing is normal” and that devoting a great deal of time and energy to arguments is “part of life.” But sitting down, listening to one another, and taking time together are often considered a waste of time or are quite simply not considered at all. Are we so allergic to well-being, the pleasure of being together, peace itself? Or is it difficult for us to believe that well-being, the pleasure of being together, and peace can actually be built up?

Each of us has the power to make war or to make peace.

For me, it’s a matter of urgency to revise our old patterns; each of us has the power to make war or to make peace. Faced with any situation, we choose our behavior: Constrain the younger daughter and repeat the scenario every morning or understand the younger daughter and connect with one another more deeply every day. We have that power in our hands.

Empathy: Being Present With Oneself and Others

Karim—swinging over to trust

I give the following example to illustrate the fact that the here and now takes root in our inner security, born of our self-knowledge and our confidence in our ability to listen, our ability to receive another’s message and take it in.

Karim is a twenty-year-old who suffers from a serious drug addiction and has been unable to break free. He joined the association for young people I belonged to. He was unemployed and had no plans. He lived alone in a small one-room apartment. I had just bought a house I wanted to refurbish, so I suggested paying him to paint and renovate the house. In the end, he settled in one of the rooms in my house and stayed for four or five months. He enjoyed the work because he saw his efforts producing results, day after day, and even hour after hour. As he was satisfied and tired in the evening, his consumption of drugs dropped dramatically. At the same time, a relationship developed between us, based on friendship and trust.

One day he said to me, “I’m deeply grateful to you. Not only have you given me work and an opportunity to earn my living, you give me shelter, and I’m no longer all alone. But most of all, you trusted me when I no longer trusted myself.”

Sometime later, he fell in love and left to live with his partner, two hours by car from Brussels. We kept in touch for some time. Then he moved again and did not give me his address, so nearly two years went by without any news from him. One weekend when I was at my father’s place in the country, he called. I was completely taken by surprise—two years without a word and then this call to a number he did not know before he left. That was strange. Here is a summary of the conversation we had, which in reality lasted nearly an hour.

“Thomas, this is Karim. You’ll be surprised to hear from me, but things are not working out at all with my partner. I’m alone again. I’m going crazy. I’m going to shoot myself or throw myself into the canal. She’s crazy. I’m crazy. Life has no meaning. We beat each other up. It’s not possible! You’re the last person I’m speaking to before I kill myself!”

To say Karim was in a state of panic would be an understatement. His words came tumbling out as if he had held them in for such a long time that only a torrent of words could relieve him of the pressure that had built up, as water behind a dam that is finally released. I first of all listened to him at length without interrupting. When he slowed down a bit, showing that the pressure was decreasing, I tried to connect with him by expressing my empathy for his feeling and needs:

“Karim, it sounds like you are feeling completely desperate (F), and I can see that it’s difficult for you to believe that your relationship can improve (N).”

“I tell you, it’s over,” he screamed again. “What a mess! I can’t believe in anything anymore. All I need is a bullet in the head.”

“It does look as if you’re at the bottom of a hole (F), and life has no meaning anymore (N: that life has meaning) and you prefer to get it over with (R or A—action). Is that how you’re feeling?”

“It must be very painful (F) for you to see that your relationship isn’t working out as you had wished (N: that the relationship should evolve satisfactorily), and there’s such a fear of being alone again (F) that you would rather cut yourself off from this suffering or protect yourself from it (N: protecting oneself from suffering), and you’ve come out with no other solution than putting a bullet in your head (R or A).”

“Well, yes … I can’t think of anything else.”

“You must be in such pain (F), and you can see everything collapsing. Nothing is worthwhile anymore (N: that things should stay in place and have meaning). Is that right?”

“Yes, that’s right.”

(Silence, a long silence.) I can hear him breathing more calmly. I go “Hmm, hmm” for a while, listening, alert to what he is experiencing and what I myself am experiencing (also to show him that my silence is presence). Then, I resume:

“Is it OK for you if I tell you how I feel in relation to all that?”

“Well, you can try.”

“Well, first of all I’m deeply touched that you would call me (F), that you would have gone to the trouble of finding me here this weekend.”

“You’re surprised, aren’t you?”

“Well, yes. How did you find the number?”

“I called the association’s secretary, who said that perhaps you’d be there. And it worked.”

“Well, I’m really grateful (F) for your confidence (N) and that you wished to speak to me from the depths of your distress.”

“Grateful?”

“Yes, I receive your trust as a gift of friendship, a friendship of the heart that isn’t burned out just because two years have gone by, but that is alive between us. And that trust and friendship, you see, is what I cherish more than anything.” (Silence.) “Perhaps that surprises you?”

“Yes, somewhat. I see myself as so useless and hopeless that I don’t see what I could contribute to you.”

“Do you feel surprised (F) because it’s difficult for you to believe (N: need to believe that sharing one’s pain is useful) that sharing your pain could actually be a source of joy?”

“Well, yes.”

“For me, it’s the joy of being together, of looking at things together, of seeking together how to go forward. The joy of counting on each other. You give me the joy of being with you, even if it is in suffering. How do you feel when I say that to you?”

“Better. That’s nice for me to hear. It even helps me relax a little.”

“Now, I know from experience that in a relationship one can stub one’s toe on the same stone, and one doesn’t see it because of being too close to the situation. Would it suit you to talk about it one evening so we can better understand together what’s going on?”

We went on chatting a bit more. He regained confidence, seeing doors ajar here and there, which a half-hour earlier had seemed to him to be bolted shut. He was betting on life again. We both ended the conversation with warmer hearts and an agreement to meet again within a couple of weeks. (Karim isn’t out of the woods yet, but at this writing he’s doing much better again.)

Remarks

What is dangerous is not going through a suicidal phase; what is dangerous is not listening to what is happening during that phase. Underlying the desire to die is a desire to live that has been disappointed, perhaps bitterly so.

I witnessed similar cases when I started working with young people. I had never been trained to listen, and often I used such clumsy tools as the following:

Denial or reduction: “Oh, it’s not so serious; you’ll get over it; life is wonderful, come on.”

Moralizing/advice: “Such-and-such relationship isn’t good for you. Get out of it.”

Advice: “Come and play some games. That will be a change for you.”

Returning to self: “You know, I too have been through difficult times …”

In those sincere but largely misguided efforts I was denying the others’ suffering or was seeking to deflect their attention from it, too afraid myself of the idea of suicide, fearful of the small suicidal part of myself that I had never taken the time to listen to or domesticate. I was, therefore, not available to listen to the distress of others, to move into their pain with them on an equal footing. I was trying to skirt the issue. Finding that looking at a festering wound was intolerable, I was attempting to distract the injured person by drawing their attention elsewhere, or I simply covered the thing over with a layer of ointment and a big bandage.

It is well known that to tend a wound, you need to clean it, that is, look at it closely to see what is hurting and why, get into it, get right inside again and again, and only then let it air, rest, heal. It hurts, yes, but it ends up hurting even more if real attention isn’t given as soon as possible. And the hurt of dressing a wound seldom harms it. In short, what hurts does not necessarily harm … and often helps.

What hurts does not necessarily harm … and often helps.

When it came to reflecting Karim’s pain back to him in the way I did, previously I would not have had the inner security or the trust in myself, in the other person, and in life to live through a long silence, to welcome Karim, and to offer him my presence after saying, “Nothing is worthwhile anymore?” I would immediately have attempted to supply him with all manner of solutions and good advice to reassure myself that I was doing everything that could be done. That’s because what I had learned best was to do things rather than to be and be with.

If today I manage to support people at the bottom of their pit in a more satisfactory way, it’s because I have understood that what they need most is presence, to not be alone. Karim saw himself (and he said so) all alone again, that is, abandoned and rejected, which was the essential drama of his life.

If I display for him all my solutions, my good reassuring advice, I am not taking care of him but of me, of my anxiety. I am not with him, but with me, with my panic or my guilt at the idea of failing in “my duty to do good.” So then he is more and more alone, more and more convinced that no one can understand the extent of his distress. And then the only solution for such a person is suicide, the ultimate anesthesia. Whereas, if through empathy I reach him, if I accompany him in his distress with my fully compassionate presence, he has a greater chance of feeling less lonely. Doubtless he is experiencing great pain, but at the same time we are together. And we converge on the need that lies at the very heart of Karim’s drama, as well as many others’ suffering: to count for someone, to have a place among other people, to connect, to exist in someone’s heart.

If today I’m more successful in the practice of this type of support, it’s because I have explored my own distress and continue to do so when it surfaces. I no longer discard it as I did before by running off “to do something”—see people, flirt with someone, get into activity (and then hyperactivity) in what French philosopher, mathematician, and epigrammatist Blaise Pascal called “entertainment.” I took a look at it, close up. I went in there often and observed that the only way of getting out of pain is to go into it fully. If, on the other hand, I’m pussyfooting around trying to minimize things (“It’s not serious … It will be better tomorrow”) or by going into my concrete bunker (“No, you don’t cry … Snap out of it … Think of something else”), believing that I can elbow my pain off to one side, I end up placing it right in the center and cannot get out of it.

It’s because I have gotten in touch with my own pain (some might even say “domesticated” it, though such is never completely possible) that I can hear Karim’s tale without having to immediately protect myself. Yet I don’t have to dwell on my story as I listen to another’s. It’s important that the pain of someone else is not simply a springboard or a bridge to mine, no matter how profound or fascinating my experience seems to me. If my attention is largely on how another person’s story compares with mine, I am not empathizing. The key to compassionate listening is staying present with the other’s pain—as long as it takes.

I would go a step farther by suggesting not only to be open to our emotional or psychic suffering, as well as the suffering of someone else, but to actually welcome it as an opportunity for further growth. If we want to see what this suffering means, it can be a chance to grow, to learn something about oneself, about another, even about the meaning of our life. In my experience, welcoming suffering always heralds (always—as long as we accept going in in order to get out!) profound joy, both renewed and unexpected.

Not that I would wish anyone to suffer. Let me make something clear: If we can spare ourselves pain, so much the better. Far be it from me to suggest seeking suffering, as some religious schools of thought have done in not granting individuals well-being and life in every respect. Since at least a certain degree of emotional or psychic suffering tends to be the lot of humanity, however, I suggest experiencing it as an incentive to get to a new level of consciousness, to change one’s plane of existence.

Indeed, my belief is that most often our suffering is out of ignorance. I am ignorant of a dimension of life in myself, a dimension of meaning that is walled up in a room lost inside my inner palace, a forgotten chamber. Suffering produces cracks in the wall, opens a breach, or turns the key of a secret door so I can gain access to a new space within myself, a profound and unexpected space, a place where I will get a better taste of ease and inner well-being, greater solidity, and more inner security. From that place I will be able to look upon myself, others, and the world with greater compassion and tenderness. And then the forgotten chamber opens like a balcony upon the world.

Listening at the right place

Empathy or compassion is presence directed to what I am experiencing or to what another is experiencing. Empathy for self or empathy for another means bringing our attention to what is being experienced at the present moment. We connect to feelings and needs in four ways: the stages of empathy.

Stage 1: Doing nothing

When we were young, we would often hear, “Don’t just stand there, do something,” so we dance around in a hundred and one different ways, and we’re truly incapable of just contenting ourselves to listen and be there doing nothing. Buddha suggests the following (just the reverse): Don’t just do something, stand there.

How difficult it is if we are too encumbered with our own pain, anger, and sadness to open up to the suffering of others—their anger, their sadness—and to accept just being there. Succeeding in listening to another while doing nothing presupposes that we have integrated what all human beings have within themselves: the resources necessary to heal, to awaken, and to know fulfillment. What alienates people from their inner resources, what conceals them behind a veil, is their inability to listen to themselves in the right place and in the right proportions. The inner resources are there. What is lacking is our ability to perceive them in a balanced way.

The inner resources are there. What is lacking is our ability to perceive them in a balanced way.

I’ve lost count of how many young, soul-searching people say to me something like this: “I would just like my father (or mother) to listen to me for a while when I want to talk to them about my difficulties. But as soon as I start to talk about what is not going right, they bore me to tears with all their advice. They bring out heaps of solutions that are their solutions. They tell me everything I should do or everything they did in their day. They don’t really listen.”

And this is typical. Doubtless the father or the mother, overwhelmed with a concern to “get it right,” is not available to deeply listen to the young person’s needs. They are virtually overcome by the fear of not measuring up to the perfectionistic and paralyzing image of the good father and mother, fearing that their child will get bogged down in untold difficulties. They panic at the idea that their child will be a school dropout or get into drugs, sexual excess, and/or manipulation by peers. The whole of the parents’ energy is being mobilized—most often unconsciously—in taking care of their own need for security, attending to their own need to provide help, or by the image of the good father/good mother, that is, their need for self-esteem. They are therefore not willing or able to listen in silence to another person. Being empathic with another, particularly if that other is someone close to us with whom we have significant emotional ties, requires considerable inner strength and security.

Stage 2: Focusing our attention on the other’s feelings and needs

The life within us manifests itself through feelings and needs. It would, therefore, be wise to listen carefully with the ears of the heart to another’s feelings and needs, listening beyond the words being said to the tone of voice, the attitude. To do so, we need to take time to resonate with the other person: “I wonder what they may be feeling—sadness, solitude, anger, some of each? When I feel things like that, what are the needs in me that those feelings may be pointing to?”

We set ourselves up as an echo chamber; we resonate or vibrate with the other person. You know how tambourines vibrate with one another: If you place several tambourines side by side, with the fabric parallel, and if you strike the first one, the vibration is transmitted down the line, by sympathy, to the last. Empathy invites us to vibrate out of sympathy.

Beware! This does not mean assuming responsibility for what the other individual is experiencing. That is their business. However, we do offer our presence.

Stage 3: Reflecting another’s feelings and needs

This is not a question of interpreting, but rather of paraphrasing in order to attempt to gain awareness of feelings and needs. It is of vital importance to realize that repeating or reformulating another’s needs doesn’t mean approving them, agreeing with them, or even being willing to meet them. Here is an example:

“My wife never appreciates how hard I work to earn the money she spends. She’s such a typical, demanding woman.”

“I see. You are angry, and you need respect as a man.”

Here we have not a reflection but an interpretation that maintains the “macho man/demanding woman” conflict. Yet what we really want is to check if we have truly understood the needs involved by avoiding any language that maintains division, separation, and opposition. We will hook a need onto the feeling. If we only reflect the feeling, the risk we run is of getting into complaining and aggressing.

“Are you angry (reflecting a feeling without a need)?”

“Yeah! You said it. She’s just unbearable. Now the other day …”

The person in pain continues accusing without getting any nearer to himself, without getting into his own pit. If we hook a need onto the feeling, we invite the other person to go deeper within himself to do the inner work that makes it possible to enhance both consciousness and the power to act.

“Are you angry (F) because you have a need for recognition and respect for the work you do (N)?”

The answer may be:

“That’s absolutely right. I need both recognition and respect” or …

“Not at all. I do feel recognized and respected. And I’m not angry. What I feel is sad and disheartened, and I need encouragement and cooperation.”

The reason I’m giving both responses is to show that it isn’t necessary to guess another’s feelings and needs accurately. Reflecting feelings and needs is like throwing the other person a lifeline. A response of this nature, on the one hand, is an incentive for the other person to look inside, to go deep down and ascertain an inner state. On the other hand, it demonstrates to the other person compassionate listening, which is needed to become aware of inner resources. It is, therefore, active listening. We are present and are displaying our presence by accompanying the individual in their exploration of their feelings and needs. The listening will be all the more active since the other person will tend to go back into their head, into a mental space, possibly needing help to come back to their feelings and needs.

If the man says, “In any event, all women are demanding, and nothing will change that,” we won’t pass by a “mental” sentence such as that because it is both a judgment and a category. On the contrary, we’re offered an opportunity to look at an invaluable need. Marshall Rosenberg rightly observes that “judgments are tragic expressions of unmet needs.”15

“Judgments are tragic expressions of unmet needs.”

We might, for example, go on as follows:

“When you say that, are you disheartened (F) because you would like human beings, and particularly women, to be more understanding and cooperative (N)?”

“With my woman, that is not about to happen!”

“Are you sad (F) because you would love to be able to trust her, believe that she can change, believe that she has the resources in her to change (N)?”

“Oh, of course. Naturally, she has amazing qualities. But she cuts herself off from most of her qualities. She is armor-plated.”

“As you say that, are you perhaps feeling divided (F) between one part of you that feels quite touched (F) by the qualities (N) your wife displays and another part of you that is disappointed (F) that she makes so little use of them (N)?”

“Yes, that’s right. I’m very touched by this woman and feel so close to her caring, compassionate side. At times she shows such sensitivity! But she’s so afraid of showing this side because she says she has been hurt in the past. And I’m sad when she doesn’t offer me the gift of her sensitivity.” (Silence.) “Isn’t that funny? Just now I was judging her as demanding, and now I see her as a sensitive and attentive woman who has gotten caught up in this game.”

“How do you feel when you notice that?”

“Moved, at peace (F) because I understand better (N) the game we’re both playing.”

“Do you mean you also see yourself included in this insight in relation to her?”

“Quite so. And as both of us are playing our games, we’re not always in a genuine relationship.” (Silence) “I need to change, to take off the mask, to show her who I really am and not who I would like her to see me as.”

“Specifically, what can you do along those lines?”

(Silence) “Ask her if she would agree to listen to me for a while and dare to say to her what I’ve just shared with you.”

Remarks

Empathy literally means “staying glued” to another’s feelings and needs. It also means putting yourself in the other person’s shoes. This means, on the one hand, you invent nothing, no feeling or need, and you attempt to get as close as possible to what the other is feeling by putting their feelings and needs into words; on the other hand, the other is urged to listen carefully and explore their feelings and needs rather than going up into their head, their intellect, into cultural, psychological, or philosophical considerations. The other person guides us, shows us the way.

Thus, in the “All women are demanding” example I don’t argue back, saying, “Not at all, not all of them, I know some men (including yours truly) who …” or “You’re right, they are unbelievable …” This would simply result in our going ‘round and ‘round, strengthening either the separation or the confusion. On the contrary, I keep up with the proposal, I accompany it by staying “glued” to what the other person is feeling and experiencing behind the words being said. For example, “Do you feel disheartened because you would like other human beings and especially women to become more understanding and cooperative with each other?” By doing that I’m inviting the other person to leave the world of images, ready-made categories, and prejudices propounded automatically by generations of people over the centuries—to connect with what is alive in them and bring them to life at that precise moment. I suggest that the other person direct their awareness toward what they truly want, a genuine need, concealed behind the catchphrase, habits of language, and particularly complaints.

I’m often aware of what I don’t want, and I complain about that to someone who does not have the skills to help me. I can work on my consciousness of what I want and address my request to someone who has the relevant skills.

When we complain, we often tend to identify with what we don’t want or no longer want. Then we talk about that to someone who isn’t able to help us. This is a recipe for spending a hundred years of one’s life complaining, while changing nothing. Our conscience and Nonviolent Communication help us identify and become aware of the need underlying the lack and to share that with a person able to help us—that person often being oneself. Thus, in the recent example of the man who acknowledged that “both of us are playing our games” and expressed a readiness to change and open up to his wife, here is a person who has left complaining and moved into assuming responsibility for himself.

Empathy is the key to a quality relationship with both ourselves and others. It is empathy that heals, relieves, nourishes. Look carefully at your sadness, your distress, your loneliness when these emotions get hold of you. Do they not stem from not having been made welcome, listened to, understood, and loved as you would have liked? Look at the suffering occasioned by grieving, a separation, the failure of a project. If you’re alone to endure the pain, it is hell. If you’re connected empathically to one or more caring individuals, to a family, then the situation is very different because you can share what you’re experiencing in an atmosphere of understanding and mutual esteem. It may even be an opportunity for renewed communion and a transformed well-being, as profound as it is unexpected, if you can seize this opportunity to move to another level of consciousness.

In the example, I showed that it wasn’t necessary to guess another’s feelings and needs accurately. But it was useful to propose a feeling and a need to the other person, to help them reach that level themselves. I recently had an opportunity to illustrate this point with a group of students. We were working in a poorly heated classroom in the middle of winter, and the end of the morning was approaching. At one stage, I asked a girl the usual two-part question: “How are you? How are you feeling?”

She replied, “Hmm … I’m all right.”

Then I continued, “Are you thirsty?”

She said, “Yes.”

“Are you cold?”

“Yes.”

“Are you hungry?”

She answered, “Yes,” laughing.

“You see that if I ask you more precise questions, you observe that you aren’t all that well after all. I didn’t force you to be hungry, cold, or thirsty. What I did do, though, was to invite you to check if you were in touch with those needs. You might well have answered no to my three questions or have added, ‘But I do feel tired’ if that had been the case. I threw a line to invite you to pay greater attention to yourself rather than answer in some automatic way. That is what empathy proposes—listening to oneself in the right place.”

Stage 4: Noticing a release of tension, a physical relaxation in the other person

Our nonverbal language often shows when we’re feeling understood, joined. Waiting for this sign is invaluable in checking whether the other person feels understood or is ready to listen to us.

In the exchange with Karim, that moment came clearly. Karim was in no way open to listening to me as long as he had not been listened to himself. With Kathy it took a little longer.

Kathy—allergic to empathy

I observe that most people have a huge hunger for empathy and feel deep well-being when they’re listened to in the realm of their feelings and needs, rather than in excessive talking or chitchat. At the same time, I also see people who have so lacked understanding, compassionate listening (free of judgments), and a nondirective openness to who they are that they’re even allergic to empathy. It’s as if being joined and understood by another person would dispossess them of the most precious thing they have built up: their rebellious, misunderstood identity; their shy and dark loneliness; their pervasive, inconsolable sense of ill-being.

Once again, there is fear of the unknown, but here it takes the form of existential angst: “I’ve always fought, always protected myself, always kept on armor. Will I survive if I open up, if I speak, if I give up any of my weapons?” Human beings as wounded as that need a great deal of silent empathy, for often they categorically reject words. This ranges from “F--- off … shut your trap … none of your damn business” among street kids to “I can’t stand the psychobabble and the wishy-washy concepts; I like things clear and logical!” from educated adults who see themselves as prim, proper, and all business. By dint of thinking and “thinking right,” they no longer dare to feel anything. Going a step farther, they no longer dare to exist.

The vigor of the rejection often reflects the depth of the need, as the example of Kathy illustrates.

A few years ago, I was canoeing down a river for a few days with about twenty young street people, or people living in group homes, in a very sunny, lovely region. Kathy had been abandoned by her mother at birth and was put into a home. For a fourteen-year-old kid, she had vocabulary that would have staggered a veteran prison guard. It was impossible to talk to her without getting back a whole truckload of swearwords, indecent images, and other expressions of her energy and vitality.

From the first few days, as we went down the river under a remorseless sun, I had suggested she put a long-sleeved shirt over her T-shirt to avoid getting sunburn. Able for once to be in the sun, she didn’t want to lose a second of it. That was understandable, but …

Come evening, when we set up camp, her arms were stiff with sunburn.

“Kathy, I have after-sun cream if you want some. I’m afraid your sunburn may hurt tonight.”

“I don’t give a rat’s a--. Go f--- your mother …”

“OK, Kathy, no problem. I’ll leave it there. If you want some, help yourself. Nonetheless, I do recommend you put on a shirt tomorrow, otherwise you’ll burn even more. The sun is much stronger here than back home.”

“Do I have to tell you again? Shut your face! Leave me alone.”

The next day, she again spent the whole day getting as much sun as possible without covering herself. In the evening, she was all red and stiff with burns. This time there was some blistering.

“Kathy, I think that must be hurting quite a lot. My cream is on the stone behind my bag. If you want, I can help you for your neck and back …”

“F--- you! Hands off, voyeur.”

“OK, Kathy.”

She left to put up her tent. I was looking and saw that she couldn’t do it. She saw that I was looking and called me.

“Hey, you bloody idiot! Can’t you help me put up my tent instead of sitting there messin’ with yourself?”

Playing it down the middle, I said, “Sure, Kathy.” I think I managed to suppress any “tone of voice.”

Then with a wink, I added, “You also may call me Thomas rather than ‘bloody idiot’ if you like.”

At that she giggled. I helped her put up her tent. We chatted a while. In our conversation the gentleness of the little girl peeked out from under the mask of the rebel. I went back to what I was doing and put after-sun cream all over myself. I then heard Kathy call me by my first name, showing me her red forearms, fluorescent with sunburn: “Hey, Thomas, why don’t you put some on me too?”

For that evening, the forearms were enough. The following day, she also accepted the nape of her neck and her shoulders. After that, it became our little ritual. Every evening of the journey, she would come to me and ask for this little refreshing massage, which was also an opportunity to casually receive tenderness and talk. We had come to terms with each other. Several contented sighs were further evidence of this.

Recall the fox in The Little Prince: “I would like you to tame me,” said the fox. “But what does tame mean?” asked the Little Prince. “You see, I’m a fox like any other fox for you, and you are a little fellow like so many others for me. However, once we have tamed each other, we shall become unique, one for the other.”

Becoming unique for another, being unique in another’s eyes, is doubtless what Kathy had been awaiting for fourteen years—being grounded, identified, welcomed as unique. Having missed out on all that to such an extent was a suffering so great that she couldn’t accept my first overtures, which she interpreted as intrusions.

When we got back, she was picking up her luggage to load it onto the bus to go back to her home in a large French city when she dropped her two bags, looked at me, smiled, and said: “I don’t want to go back home. Will you adopt me?”

An opposition toward empathy occurs in many marital and family relationships. Some people have accumulated so much suffering in relationships that they can’t take even one word, even a loving one, from this other person. For both the people concerned, a situation like that is extremely painful. The one who keeps the relationship closed suffers from shutting themselves off (without being aware of it, of course) in their distress. They are trapped and don’t want to believe that they hold the key to the trap. They have almost overwhelming feelings of powerlessness and loneliness.

The individual in the boat who’s trying to throw a line to the other person soon starts to suffer from not having their good intentions and efforts recognized or welcomed. Often, out of despair, this person in turn essentially gives up and gets aggressive in return. That only confirms to the first party that they were right to keep the barriers up. The vicious circle—even the spiral of violence—has begun. And it can last for centuries. Just look at the tribal or family hatreds that have lived on from generation to generation!

What can be done?

When we’re desiring to open a closed door

For the person who wants to keep the lines of communication open: First, avoid any aggression. That only begets aggression. However, if the situation has existed for some time, a healthy outburst of anger expressed in Nonviolent Communication will often make it possible to clearly express frustration without committing acts of aggression against the other party. We’ll see later how to express our anger forcefully without being aggressive toward anyone.

What frequently happens, though, is that the person who would rather sink than swim (with someone else’s help) takes everything personally. In this case, even an outburst of anger expressing needs with no aggressiveness can be taken as an act of aggression.

What remains is silent empathy—empathy from the heart.

What remains is silent empathy—empathy from the heart. This calls for inner-empathy work so that one doesn’t in turn get caught up (or bogged down) in the spiral of aggression.

In my view, the only way to refrain from getting into the vicious circle or spiral of violence is to maintain compassion, receiving within oneself both the suffering of the other party and the suffering that their behavior engenders in oneself, and work to get to a place of inner peace whatever the circumstances. Each of us is responsible for the war or the peace maintained in our own heart.

This work can require help if we don’t feel we have the strength to stand up alone to the spiral of violence. Personally, I have been able, on occasion, to sense a need for outside support and have asked colleagues to listen to me or give me empathy at times when I believed I was on the verge of switching into aggression, whereas I wanted to stay compassionate.

Naturally, I might have been able to obtain certain results by exploding aggressively. For example, throwing an alarm clock on the floor may get it going again, but it also might smash it to smithereens. Or I might lose an eye if a spring pops out the wrong way! I no longer have a taste for attempts to “resolve” conflicts in this way. I have too great a concern about such strategies backfiring. Now what I seek is not so much a result as a climate where the two of us can connect. Maintaining a climate of empathy, even unilaterally, is more pleasant for me than nursing resentment.