11

Admiral Richard Bennis: Captain of The Port, 9/11

In Dick Bennis, we had the right guy at the right time in the right place.

—Admiral James M. Loy, US Coast Guard

On the morning of September 11, 2001, US Coast Guard Admiral Richard Bennis with his wife Gloria was driving south in their jeep to look at potential retirement properties, someplace they might spend some time fishing. They had always had a small fishing boat of some kind, Gloria said, and especially enjoyed fishing for grouper in Florida. The previous day in New York City Bennis had staples removed from the back of his head from the cancer surgery he had endured earlier in the summer. The admiral had been in the Coast Guard for close to thirty years and he and Gloria thought that maybe it was time to slow their lives—but it was still just a maybe.

At Quantico, Virginia, where they had stayed overnight, they got into their car for an early start when Bennis’s deputy at Station New York, Captain Patrick Harris, called. In Bennis’s absence, Harris had just convened the morning staff meeting at their Fort Wadsworth Coast Guard base on Staten Island. “You’ve left town again, Admiral. And something always happens when you leave town,” Harris said. Last time it was someone pulling a stunt and getting his parachute caught in the Statue of Liberty torch. But this was no stunt.

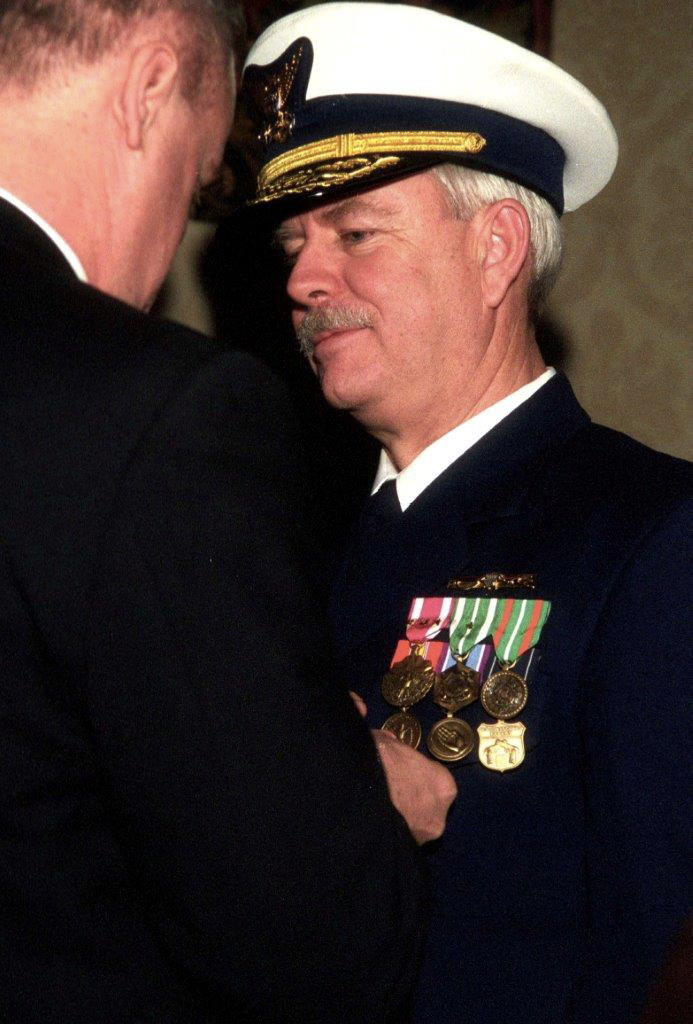

Rear Admiral Richard E. Bennis

Courtesy US Coast Guard

“We pulled off the road and I got the portable TV from the trunk,” Gloria said. “I saw the plane hit. This was the second plane, but at that moment I thought it was a rerun of the first one.” They immediately turned around and headed to New York. As captain of the Port of New York and New Jersey and commander of Coast Guard activities for New York, Bennis was in charge of the largest operational field command in the Coast Guard. “He drove with the lights flashing. Most people let us go by,” Gloria recalled. It was more than two hundred miles to the city. As they were crossing the Potomac over the Woodrow Wilson Bridge they saw a huge ball of black smoke rolling out of where the Pentagon should be. They were stopped at a bridge but once Bennis showed his credentials, they were allowed through. “We drove eighty to ninety miles an hour and the police didn’t stop us,” she said, although she was frightened by the speed for the two-hundred-mile trip. “They assumed we had to get somewhere.” The Bennises got a call from their son Timothy at the base near the Verrazano Bridge when armed officers stopped him from going into their house. “They put guns on him until he passed the phone to them so they could hear from the admiral that it was okay. The Bennises were told to drive to Sandy Hook where they would be met with a boat to take them to Station. “It was eerie. I was scared for my family; I wasn’t sure where they all were at the time.” The Bennises had another son and daughter as well as a grandson.

“For the next thirty days, he never stopped working,” Gloria said of her husband.

Station New York: Where He Wanted to Be

Bennis had asked to be stationed in New York. He was particularly interested because of OpSail, the event that would bring more than a hundred tall ships, forty warships and more than seventy thousand small boats into New York harbor in 2000, and would require creating a special plan for security. Little did Bennis know then how useful that plan would be a year later. While he was stationed as captain of the port in Hampton Roads, Virginia, which he called a dream assignment, he explained to Commandant Admiral James Loy, “I heard that New York was going to come open and I decided to put in for it. Throw me into the briar patch. I knew OpSail 2000 was coming and I thought that was the greatest peacetime gathering of ships in history, and it sounded like a pretty good bone to chew on.”

Bennis described it to a reporter from the New York Daily News as “the waterborne equivalent of directing traffic in Times Square on New Year’s Eve.” OpSail 2000 kicked off seven days and nights of celebrations of the millennium and America’s 224th birthday. As many as four million people crowded seventeen miles of shoreline around New York harbor to take it all in. When it was over Bennis looked forward to a year of writing about what had been learned from OpSail, while anticipating his next assignment from the Coast Guard. (He had been in New York for two years and it was traditional to be reassigned every three to four years.) It was then Bennis learned he had incurable melanoma, the cancer that eventually invaded both his lungs and his brain. Bennis refused to acknowledge the prognosis that he had six months to live, so he underwent eight hours of brain surgery, had a metal plate embedded in his skull and went back to work a day and a half later.

The Early Years

Richard Ellis Bennis was born in Syracuse, New York, but he grew up in Wyoming, Rhode Island, a small town near Providence, with his parents Winifred Turner and Mason A. Bennis and his sister Joyce. Gloria Smith met Richard Bennis in sixth grade. They had a rather long bus ride to school, so became friends. “He made me laugh,” Gloria said, but it wasn’t until they went to the high school prom together that she realized they were much more than friends. That summer Bennis went on an extended trip to Canada with his dad, who soon realized something other than the trip was on his son’s mind. The couple married in 1968 while both were in their second year of college and began a family. After earning a bachelor’s degree in natural resource development from the University of Rhode Island, Bennis enrolled in officer training school with the Coast Guard, receiving his commission in 1972.

Like most military organizations, life in the Coast Guard meant moving a lot, which could be hard on families. The Bennises lived in Texas, Florida, Virginia, Charleston, and New York. “Our oldest son didn’t like moving; most tours were three to four years, but in Washington, DC, we held out for five years so he could graduate high school. However, Gloria said that by that time they had made close friends, “and it was even harder to move.”

In his off-duty hours Bennis enjoyed reading military history and Tom Clancy novels. And he loved to restore cars, especially the original Volkswagen Beetles. As Bennis himself described it to the Coast Guard’s historian, “I had a ’71 Super Beetle convertible; candy apple red, and I believe in driving them after you fix them. I had my surgery and it was one of my first or second days back at work for the very first time and I almost got run over by a fire truck. I pulled over to the side of the road, got my cell phone and called my wife, and I said, wouldn’t it just piss you off if I went through all this, I lived, and I get killed by a fire truck the next day. I mean it’s the way it is, you know, you never know.”

An Environmental Expert on Oil Spills

During his career Bennis earned a master’s degree in energy and environmental studies from Harvard and developed an expertise in handling spills of oil and other hazardous materials that was well known, especially in East Coast ports. He served as captain of the three largest East Coast container ports: Charleston, South Carolina, Hampton Roads, Virginia, and New York.

In 1992 Bennis was credited with saving the crew of the container ship Santa Clara, and the adjoining port area of Charleston by averting the explosion of highly unstable materials spilled onto the deck during a storm, and which could explode if exposed to water. In addition to saving the ship and protecting the crew and surrounding community, Bennis devised a method of eliminating this type of threat and his action led to national improvements in shipping container safety and inspection. He led the Coast Guard Office of Response as it updated the way it dealt with everything from oil spills to fires, explosions, natural disasters, and search and rescue missions.

The Coast Guard awarded many medals and commendations to Bennis for Meritorious Service and Achievement. In 2008 a channel (called a reach) leading to a harbor in Charleston was renamed Bennis Reach by the South Carolina legislature on a recommendation from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). This was the first time a reach was named for a person.

A Boatlift Compared to Dunkirk

But on that fateful morning of September 11, thoughts of retirement and fishing with Gloria were put on hold indefinitely as their lives changed forever. While Bennis directed operations from his cell phone not only for the evacuation of crowds flocking to the waterfront from the World Trade Center, but to close the port and stop any inbound commercial ships and boats at Ambrose Light (see chapter 7). There were already a dozen commercial ships with fuel waiting to enter the nation’s largest oil port, where the fuel was then distributed to locations all over the Atlantic Coast. The Port of New York and New Jersey is the economic nerve center of the East Coast with its oil and chemical storage tanks, tunnels, power grids, and container port facilities. It was important to get those supplies delivered, but nothing could enter the harbor until it had been thoroughly searched by the Coast Guard to secure it from maritime threats.

The biggest concern during the first 24 hours was the possibility of more attacks. They worried about the Statue of Liberty, the Indian Point Nuclear power plant, as well as all those chemical tanks lining the New Jersey side of the harbor. Everything Bennis had strategized for the previous year’s Op Sail event was put into action, including the possible evacuation of Manhattan and where to set up triage sites.

One of Bennis’s officers in a patrol boat described a literal monsoon of dust rolling from the Twin Towers toward the Battery, which became so dark people could not see. Paper and debris were flying everywhere, and what appeared to be the entire population of lower Manhattan was racing inside this dust cloud to the waterfront, desperate to flee the island. Crowds were knocking each other over in their panic to get away. One witness described a hot dog stand in Battery Park lying on its side, and even an overturned baby carriage.

Amid the smoke and dust the Coast Guard used radar to navigate their way around them. Officers passed out gas masks, and unloaded water for people scorched by smoke. They directed them to medical centers that had been set up, and tried to maintain some sort of order with the commercial tugs and other boats coming in to take people off. Terrified people were jumping onto the decks of any boat they found close by.

At the time the Coast Guard did not keep a large fleet of boats in the harbor. They had a few tugs, two patrol boats, lifeboats, inflatables, and utility boats, complemented by the 175-foot-deep class coastal buoy tender Katherine Walker (see chapter 8). But there were plenty of other boats in the harbor that could come to the rescue of the thousands of panicked people trying to find some way out of the chaos to get home to their families. Ferries, tourist boats, fireboats, yachts, dinner cruises, tugs, and other work boats were all put into action. Bennis directed his crew as they organized a flotilla of more than one hundred boats, many crewed by volunteers, who brought the people to safety and often brought back much needed supplies on the return trips. By the end of the day five hundred thousand people had been evacuated from lower Manhattan.

The retired 1931 fireboat John J. Harvey, which had greater pumping capacity than any active duty New York City fireboat at the time, pumped river water to fire trucks, which could not get water from the broken water mains at Ground Zero. The Harvey, which had been retired in 1994, was on the National Historic Register and was maintained by a crew of volunteers. Dinner boats provided floating cafeterias and resting areas for exhausted workers.

Later, this waterborne rescue of half a million people from Manhattan would be compared with the evacuation of Dunkirk in 1940, where allied troops trapped by the German army at this north coast seaport of France had no means of escape other than the English Channel. Private boats sped across the Channel from Britain to the rescue, but that evacuation took nine days.

In 2011 a twelve-minute film about the 9/11 event, Boatlift: An Untold Tale of 9/11 Resilience, narrated by Tom Hanks, was funded by Center for National Policy and was produced and directed by Eddie Rosenstein Eye Pop Productions. It is available on the Internet (www.road2resilience.com).

The Right Guy in the Right Place at the Right Time

Coast Guard headquarters in Washington was nervous about what was happening and Bennis needed to reassure them. “I would take my little bitty cell phone, and I’d take it outside the command suite and I’d lean against the bicycle rack near the galley, because that was where I had the best reception.” He programmed his phone so he had a button for his commanders in Washington and Boston.

“And I’d call them on this tiny cell phone and give them the status report, telling them what we were doing, and that I would call them in forty minutes, an hour, and hour and a half. And I said to the commandant, “You need to know that everything we need to be doing, we are doing. We’re doing it well. But we need more people, and more logistics support.” The only thing they couldn’t really do was demonstrate it to those officers outside of New York because of the lack of communications. Even two months later, as the site continued to burn, Bennis kept up his daily briefing. Finally phone lines on Staten Island were rerouted through Denver. When he got his new phone and called his wife, she told him that the caller ID read Tony’s Pizza. “Don’t ask why,” Bennis told her. “It works.”

Bennis told his superiors he knew what he wanted to do and from working with the city the best way to accomplish it. “But what I wanted to know was, was I in fact a free agent? And I was. And at the start I need to know if I was going to have that freedom or were they going to micromanage me. They didn’t send in a team to oversee the operation. Instead they sent exactly what I needed, the people I needed. It worked out very well.” Bennis himself was never a micromanager. He felt his staff was well trained and if they could not reach him for approval and believed they were right and needed to act then they should go ahead. Pat Harris described his technique: “He would say, ‘go make magic and be brilliant.’”

The plans previously made for OpSail included all kinds of contingencies for that event, including an appearance by the president, which occurred a few days after 9/11. When 9/11 occurred, they went through all of those plans. “That’s why Bennis thought his cancer was meant to be,” Harris said. “Everything we ever learned, we used that day and in the six weeks after it.”

Bennis visited Ground Zero often during those days, when the commandant from Washington was there and he accompanied New York officials as well. “The first Sunday afterwards, my wife and I went there with several of our chaplains,” he said, “just to be with the folks that were there and the folks that were responding there.” His son Tim, who worked for Moran Towing at the time, was helping decontaminate the site, as barges towed away the ashes and other debris.

Charting a New Course for the Coast Guard

Bennis led a round-the-clock effort designed to increase the Coast Guard presence in the port of New York and New Jersey by 500 percent, changing their primary mission from protection to prevention. He charted a new direction for the entire Coast Guard as it entered a new phase in history.

Until 1996, the Coast Guard had been stationed on Governors Island and some felt that leaving this base close to the tip of Manhattan had compromised its ability to quickly respond to any emergency. Others noted that it would have made it difficult for them because their own families would have had to be evacuated from the cloud of dust. Fort Wadsworth was the right place to stage the evacuation. A Coast Guard utility boat can cross from Staten Island to the Battery in about fifteen minutes.

One of the first things Bennis did when he got to Manhattan and evaluated the scope of the devastation that first day was to put out a call to the rest of the nation’s Coast Guard to send everything to New York. He wanted fast boats to be taken out of mothballs and sent to New York to increase Coast Guard presence, to reassure the population they were being protected. They had thirty-eight-foot deployable pursuit boats (DPBs), the guard’s “go fast” boats for chasing drug-running boats. These had been mothballed in recent years in Virginia, but have found their element in the harbor.

“Without knowing it, that is what those boats were designed to do, where they were meant to be.” Bennis believed they were a very good tool for a public that respects and appreciates the Coast Guard while at the same time believing that “the Coast Guard can’t catch a Boston whaler.” They got the DPBs early on and “I would have them run from the George Washington Bridge to the Verrazano Narrows Bridge at speed several times a day, just so people could go, ‘What the hell was that?’ It’s the Coast Guard. Just knowing we had that capability gave a lot of people pause, be they tourists or people intent on violating a security zone.”

Until then the public was used to seeing one or two Coast Guard white boats with the orange stripes working in tandem with the New York Police Department’s blue boats with white stripes. Now they were seeing forty-five or fifty Coast Guard boats. Bennis also made sure that the media carried as many pictures as possible of the gray-hulled, black-striped port security boats (PSUs), so they knew this was a different operation. In the past, such boats were not used domestically, but now they were, so the public knew there was a heightened level of security from the Coast Guard.

In strengthening its harbor presence during the weeks after 9/11, Bennis led the Coast Guard in changing its mission from response to prevention. Security enforcement patrols were brought back to New York harbor for the first time since World War II. Maritime security before 9/11 was a relatively small priority in the overall scheme of the nation’s commercial shipping and port operations. Two major exceptions were the world wars. During World War I, with the Espionage Act of 1917, the Coast Guard first designated officers as captains of the port. These were senior officers whose job was to oversee loading of cargo, looking for any possible sabotage at a time when German U-boats were sinking merchant and passenger ships.

For most of its three-hundred-year history, the Coast Guard was under the auspices of the Treasury Department. That changed after 9/11 and, along with the National Guard, Customs, the Secret Service, Emergency Management, and other local and federal agencies, responsible for the nation’s security, the Coast Guard came under the umbrella of the newly created Department of Homeland Security. In November 2002 President George Bush signed the Maritime Transportation Security Act of 2002.

By now promoted to rear admiral, Bennis officially retired from the Coast Guard in March 2002, six months after 9/11, but that didn’t mean he was finally going fishing with Gloria. He accepted Secretary of Transportation Norman Minetta’s invitation to become associate undersecretary for maritime and land security in the new Transportation Security Administration. Bennis’s challenge now was to develop strategies to protect the maritime, rail, highway, mass transit, pipelines, and waterways of the National Transportation System at a cost the industry and the traveling public could afford. Minetta, who had called Bennis’s work on 9/11 remarkable, said “He brings many hard-won skills into a demanding new environment.”

When he took the TSA job in Virginia, Bennis brought along several officers on his staff, including Pat Harris. He worked there for a year before the cancer finally caught up with him. Harris and his family said they were shocked when Bennis died, because he didn’t appear sick. On Sunday, August 3, 2003, almost two years after 9/11, Bennis died at Mary Washington Hospital in Fredericksburg, Virginia. He was fifty-three and was buried with full honors in Arlington National Cemetery. There was a memorial service in New York at the Coast Guard base.

“He didn’t want people to know how bad his condition was,” Gloria said. “He wanted to live. He told me that ‘If you stop living, it takes you.’”

And indeed Bennis had long passed the original six months of life that had been predicted for him. He never wondered why he had brain cancer; after the terrorist attacks on 9/11, he told a friend he knew exactly why he had gotten ill. His failing health had kept him in New York at the moment his nation needed him most.

A Continuing Presence

The US Coast Guard established the Rear Admiral Richard E. Bennis Award to honor exceptional commitment to the security of the US and the marine transportation system. Among the first recipients of the award was the Port Authority of NY and NJ’s security program in 2014.

When New York Waterways named a new ferryboat for Bennis in 2003, his family came to New York to christen it. “We all went,” Gloria said, and as is customary, she broke a bottle of champagne over the hull. In January 2009, the Admiral Richard Bennis was one of the ferries that helped rescue passengers from a US Airways jet that splash-landed in the Hudson, after a collision with a flock of birds knocked out both engines. Everyone survived, so you could say Admiral Bennis is still looking out for us in the Port of New York and New Jersey.

Ten years after the death of Admiral Bennis, Gloria Bennis lost her son Keith to the same cancer that had taken her husband. Today her son Tim and daughter Wendy and her grandchildren all live near each other outside of Charleston, not far from the Bennis Reach.

Author’s Note: Some of the dialogue with Admiral Bennis comes from the narrative taken by the Coast Guard historian after 9/11 with the people involved, which is available for use without restriction.