2

Anything Is Possible?

the plastic brain

Are taxi drivers clever? We trust that great geniuses like Einstein were. The physicist and developer of the theory of relativity, which almost nobody really understands, is estimated to have had an IQ of more than 150. We also expect philosophy professors and multilingual UN interpreters, for example, to top the intellectual performance tables. But taxi drivers? Who ferry their fares from A to B and rail against passengers vomiting in the backseat of their vehicles late at night? Sure, they have to be able to drive a car, but who isn’t capable of that? In London, they have to show knowledge of the locality to qualify for their taxi licence, but once that’s in the bag, they can rely on their satnav like anyone else. And it will even let them know when the traffic is particularly heavy on a given route. That doesn’t sound as if it requires a high IQ.

We know from real life that taxi drivers can be almost anybody. A former university professor from Tehran, forced into exile for political reasons. Or a brilliant musician, proficient not only on the violin and the piano, but also on the didgeridoo and the sitar, yet whose music does not attract audiences large enough for him to be able to make a living from it without topping up his income as a cabbie. It is impossible to say how many unrecognised experts, creative talents, and geniuses are on the roads behind the wheels of their taxis. But there are also the rednecks who spend their breaks snoozing with the latest tabloid scandal sheet over their face and complaining about the ‘immigrants’ stealing their customers. Or silent, passive-aggressive female taxi drivers who appear determined to make their passengers feel about as welcome as a dead cockroach in their morning muesli. The host of taxi drivers is extremely diverse. So, can we say anything about whether they are more or less clever than average?

No, we can’t. But we can establish a different fact. And that is that you can only get a taxi licence, or a PhD, by using your brain’s best feature: its extreme plasticity. Thus, newly qualified taxi drivers and potential Nobel Prize laureates have something in common: the activity inside their skulls is flexible and dynamic.

This is the conclusion reached by neuroscientists Eleanor Maguire and Katherine Woollett of University College London.1 In a study in the year 2000, Maguire had already established that London taxi drivers have larger hippocampi than many other people. The hippocampus, an evolutionarily primitive region of the brain, owes its name to the fact that it resembles a seahorse, with a horse’s head and the tail of a fish, and, just as that creature appears to transition from one animal to another, the main function of the hippocampus is to transfer information from the short-term to the long-term memory. For this reason, an enlarged hippocampus could be a sign of a capacity to retain large amounts of learned information. But the operative word here is ‘could’, since the hippocampus also plays a part in other functions, such as emotional behaviour. Furthermore, the hefty seahorses inside taxi drivers’ heads could have been present before those would-be cabbies decided to apply for a taxi licence, rather than having developed during driving. That would mean their enlarged sizes were the cause rather than the result of the drivers’ career choice. Thus, the mere fact that taxi drivers were found to have oversized hippocampi does not provide a reliable indication of whether this is due to changes in their brains were brought about by their profession.

So Maguire and Woollett explored the issue further. Using magnetic-resonance imaging, they began by scanning the brains of 79 people who had begun a four-year course to qualify for a London taxi licence. Forty of them failed the course, which is hardly surprising since in just the centre of the British capital there are 25,000 streets and several thousand places of interest to be memorised. The brain scans of those failed candidates showed that their hippocampi were the same size as before they began acquiring ‘The Knowledge’ — as the thorough understanding of London is famously known.

However, 39 candidates passed the notoriously difficult test. And their hippocampi turned out not only to be bigger than those of a control group and the group who failed ‘The Knowledge’ test, but also to be bigger than before they started the training course.

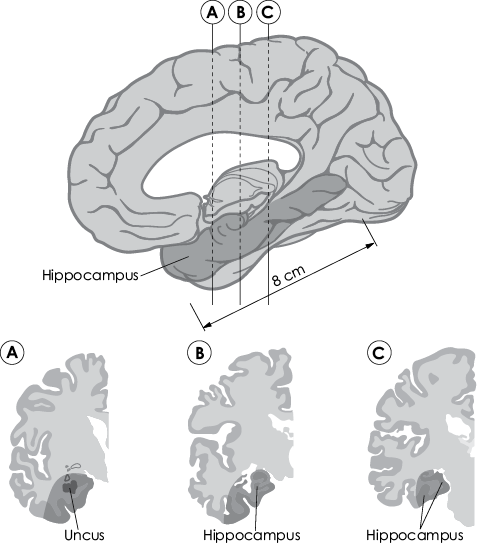

THE MAIN REGIONS OF THE BRAIN FOR EMOTIONS AND PLASTICITY

The neuroscientists could not identify anything to indicate in advance which participants would complete the training procedure successfully. The drivers’ brains were all more or less the same; in particular, each participant started with approximately the same amount of hippocampal grey matter. Yet after years of rigorous training, differences were apparent. The size of successful candidates’ hippocampi, and only theirs, had increased significantly. They also performed better in spatial orientation and memory tests. This is a pretty clear indication that their brains had not simply changed in random ways, but in such a way as to increase their functionality.

Did those trainees who became fully-fledged taxi drivers have some biological advantage over those who failed? Could it be that their hippocampi already had a greater potential for growth? Did they have a different predisposition? Or were they perhaps just more motivated? These are all questions that Maguire and Woollett have not yet been able to answer. What all this does make clear, however, is the enormous plasticity of our brains, not only as children but also as adults. And the changes made visible by scanning techniques are just one part of this huge flexibility.

The hippocampus plays an important part in the plasticity of the brain

The illustration shows three cross-sections of the brain (A, B, C), at the level of the hippocampus. The hippocampus and the surrounding areas of the temporal lobe are responsible for the associative connecting of memories to the cerebral cortex. Its destruction leads to a complete loss of conscious episodic and semantic memory. This means general facts and personal experiences can no longer be remembered. The hippocampus is particularly affected by dementia.

Stimulation and care: what really makes children’s brains grow

The plasticity of our brains is apparent on several levels. Some of those levels can easily be seen using appropriate visualisation technology, and that includes the abovementioned enlargement of the hippocampus. Such processes are based on the growth of individual brain cells, and more importantly, the layer of fat which surrounds them. These days, fat doesn’t have such a great image; in this fitness-obsessed age, fat is seen more as a passive mass and a dead weight than as a substance with a positive function. However, in the case of our brain cells, more fat means more electrical conductivity, and, of course, in an organ that works on the basis of the electrical transfer of stimuli, this increases its performance level.

Brain plasticity is also based on the creation of new cells and the formation of new, sturdier connections between neurons — an aspect that plays a crucial part in the learning process. However, these connections are an expression of not only plasticity, but also stability, since, as long as the learning processes are rewarded, those connections are not usually lost again.

Neuroscientists debate whether something once learned can ever be un-remembered by a healthy brain, since nothing is ever deleted in the brain; rather, it is overwritten, altered, and modified. A person who has learned how to ride a bicycle, swim, or play the piano but has not engaged in that pastime for the past 20 years will initially be better at the activity than someone learning it for the first time. This is because the associated neuron connections are still there, and need only be uncovered and reactivated.

However, the plasticity of the brain is also apparent within our cells, even at a genetic level. Until only a few years ago, it was believed that the genetic apparatus of our cells was fixed and always produced the same signals. Now we know that it can be altered by external influences, although only if it learned to do so early — in other words, if it gained the ability to change. Those who grow up as children in a low-stimulus environment will later lack the flexibility necessary for change — and that places a massive check on the potential for learning. Fewer connections are formed in the brain, the neurons are linked only loosely, the nourishment and growth of brain cells is reduced, and fewer cells develop in certain regions of the brain, such as the hippocampus, which is necessary for our episodic long-term memory.

The general importance of external factors on the structure of the brain has been demonstrated in experiments on rats, which were exposed either to an ‘enriched environmental condition’ (EC), including balls, tubes, and ladders, as well as obstacles to overcome in order to access food, or to a low-stimulus ‘impoverished environment condition’ (IC).2 The results showed that the brains of the EC rats were almost unrecognisable after just a few days. They had more neurons, which were also larger overall and had larger nuclei. The number of dendrites — the branched projections of a neuron that propagate electric stimulation — had also increased significantly. Overall, the cerebral cortex of the EC rats was 10 per cent larger than that of their bored peers and was better able to regenerate following the occurrence of lesions. The cerebral cortex had not only built up more mass, but also developed a better ability to repair itself. To reiterate: all these changes took place within a matter of a few days. To achieve a similar effect in a muscle would require several weeks or months of rigorous training.

Changes to the brain can, of course, disappear and become overlaid by other learning processes, but many remain intact if they developed during a critical learning phase. Studies on human subjects have revealed how powerfully and permanently environmental stimulus causes the brain to grow. Since the year 2000, American researchers have been investigating the influence of children’s environment on their development and the growth of their brain, as part of the Bucharest Early Intervention Project.3 The researchers compared Romanian children who had lived in institutions since birth with others who first lived in such homes but were later placed with foster families, and they compared those two groups with children who had grown up within families from birth.

When the researchers scanned the children’s brains, they found that those children who grew up in institutions had significantly less grey matter (made of neuronal cell bodies) and white matter (made of axons and bundles of nerve fibres) than those who grew up in family environments. Although the boys and girls who began life in institutions and were later placed with foster families had less grey matter, they had about the same amount of white matter as the children living in families from birth. This led researchers to conclude that emotional neglect and lack of stimulation causes low brain growth in children. ‘Lack of stimulation’ in this context means the children rarely engaged in play, received little attention, and had a monotonous daily routine. On the other hand, these deficits appear to be reversible, to a certain extent and within a certain timeframe, otherwise the children who began life in institutions and later grew up with a family would not have had the same amount of white brain matter as the original family children.

Having said this, the positive influence of the family should not be overestimated. Experiments with rats have shown that it is not so much the number of social contacts that’s important for the growth of their brains, but the challenges posed by their environment. Crucially, the Romanian children growing up in institutions lacked not only a consistent attachment figure, but also stimuli; games, stimulation, challenges, and a varied daily routine. Or, to put it another way, in an environment with little stimulation, brain development is not improved by being surrounded by many peers who are equally bored.

Indeed, Japanese scientists recently discovered that overbearing parents may even hamper the growth of their children’s brains. Of course, it seems doubtful that this effect is connected with boredom and a low-stimulus environment, since such parents actively seek to promote their children’s development in every conceivable way and to offer them all they can. It might be assumed that the excessive fear and worry of such parents concerning their children, and their inability to grant their offspring any independence or concede them any problem-solving skills, stunts the development of those children’s brains.

Kosuke Narita and his team from Gunma University scanned the brains of 50 men and women between the ages of 20 and 30 and asked them about their relationship with their parents up to the age of 16.4 Statements like ‘they tried to control everything I did’ and ‘they did not want to let me grow up’ were interpreted as indications of overprotective parents. The team found that subjects who were ‘smothered’ (and ‘sfathered’!) in this way had less grey matter in their prefrontal cortex (an area of the frontal lobe responsible, among other things, for self-control, emotional assessment, and memory integration) than those who were sometimes allowed to play boisterously and unsupervised in the playground as children.

Thus, overprotective parents have a similarly negative effect on the development of their children’s brains as living in a bare cage has on the development of the brains of rats. And that’s not all. The Japanese researchers compared the prefrontal cortices of their overprotected subjects with those of people who had been neglected or ignored by their fathers. And they found: no difference. In other words, overprotective parents enfeeble their children’s brains just as much as fathers who do not bother about their offspring at all.

Of course, such research results must be treated with caution, since people can lie or be mistaken when asked about their childhood. Furthermore, it is also possible that some subjects were simply born with a less well-developed frontal lobe and were mollycoddled by their parents as a consequence; once again, it could in principle be possible that brain development is the cause and not the effect of a particular environment.

Nevertheless, the fact remains: living in an intact family is far from being a guarantee of optimum brain development. When parents coddle and protect their children to such an extent that they stifle them with their love, leaving them no space to develop independently, they rob their child’s brain of one of the necessary prerequisites for its growth.

Alongside loving care, what really counts and what really gets things moving inside the skull is exposure to situations and experiences that earn individuals social recognition and that give them an image of themselves as active agents, finding their own solutions to problems and overcoming obstacles independently by discovering connections, gaining insights, and realising that they can influence and change their environment, even if all this also entails the risk of injury or failure. Passivity and exclusive consumption, by contrast, do not generally stimulate brain growth. And situations and experiences in which people feel powerless and which they are not able to change as they would like, such as anxiety, torture, or the absence of a father, can act as negative stimuli and even prevent brain growth.

The brain can still change in old age

‘Taking up Italian at 75? Impossible!’ ‘Starting a new career at the age of 50? You missed that boat long ago.’ There is a widespread opinion that learning is no longer possible in old age because our brains lose their ability to change and be changed as we grow older. But that is not the case. It is true that young neural structures react more quickly and dynamically than old ones, but that certainly does not mean that little or nothing is possible later in life.

In a recent study by neuroscientists at the University Medical Centre Hamburg-Eppendorf, 44 men and women between the ages of 50 and 67 were taught to juggle over a period of three months. Their brains were scanned before the three-month training period, after it, and three months after the end of the training.5 The control group was made up of 25 people of a similar age who were not given juggling training, who were scanned on the same days as the ‘jugglers’. After the training phase of the experiment, the jugglers displayed a localised, very specific increase in the grey matter in their visual-association cortex, which plays a major role in the perception of movement. The control group displayed no changes in this brain region. In addition, the researchers found increases in the hippocampus and the nucleus accumbens (part of the brain’s reward system) exclusively in the training group.

This and other studies show us that the brain retains its plasticity far into old age, and that means there is practically no age limit to learning. Nonetheless, there are certain phases that are especially good for learning particular cognitive activities. For example, the phase between the ages of 18 months and three years is critical for language learning, which also places limits on therapeutic measures such as cochlear implants. These are tiny computers that are implanted in the cochlea (the spiral-shaped chamber of the inner ear) and transform sound signals picked up by an external microphone into electrical impulses. These are then transmitted via very fine electrodes to the auditory nerve. This technology allows people to (re)learn to hear, unless they lost their hearing as children and didn’t receive the implant until adulthood, in which case the brain can hardly process the language signals it suddenly begins receiving. The person may develop some language comprehension, but is unlikely to be able to learn to speak normally. For this reason, it is of the utmost importance to diagnose and treat deafness as early as possible, to ensure that the auditory nerve and language centre of the brain develop optimally.

Limiting, inappropriate, and pathological patterns of perception and behaviour are also more likely to develop during certain phases of our lives. Puberty is a critical time for depression, which is often the result of separation or loss experienced during that time. By contrast, phobias, such as fear of spiders or the dark, are mostly formed between the ages of three and eight. And they develop more strongly, the more they are heeded by those surrounding the child, because attention is a kind of reward, and rewards release powerful learning impulses and strengthen the neural connections involved in information processing.

Size isn’t everything

The taxi drivers’ enlarged hippocampi, the increase in grey matter among the juggling seniors and stimulated rats — these results might give the impression that learning is mainly about increasing the size of certain regions of the brain. Like a sack that bulges increasingly, the more you stuff into it. But this image does not describe the plasticity of the brain correctly at all. In the brain, it is only at the start of the learning process that certain areas become enlarged — when a person has already become an expert, this growth moves into the background, to make room for the development of other areas.

Let’s take learning to play the guitar as an example. As we know, at first the learner must strive to attain a certain level of dexterity. This necessarily leads to growth in those regions of the cerebral cortex that control the motor skills of the fingers. Once those motor skills have become automatic — that is, when a learner can play without having to pass every plucking or fingering motion through the loop of conscious control — the finger-controlling regions of the cortex no longer need the space they originally required. They remain larger than those of a non-musician, but they will no longer be as large as they were when the guitarist first started learning to play.

The guitarist’s movements have become automatic, which means they can be controlled by the deeper regions of the brain without any special assistance from the cerebral cortex. Instead, other parts of the brain come to the fore, such as those responsible for musical emotionality and analysis. The products of these functional shifts in the brain are what we experience as great moments in our cultural history. Adept guitarists with years of practice under their belts can ‘put much more feeling’ into their playing than those who are happy if they can just manage to strum a few chords correctly.

The brain doesn’t mind — and so is open for anything

This begs the question: why should it be the areas for musical emotionality that develop when those for musical dexterity no longer require so much space? In other words, what does the brain gain from intensifying our ability to express emotions through music, once the manual skills required to produce it have become automatic? Is it hoping to gain a deeper understanding of the innermost essence of the world — in Schopenhauer’s sense — which can find no better expression than in music? Or is the explanation perhaps less metaphysical and more emotional and trivial? Namely that the brain simply has more fun performing well-practised operations with feeling. Another possible explanation is that emotional expression through music earns more respect from others. This is the view usually held by social psychologists who see the brain principally as a social organ interested in provoking effects in other people.

Which of these explanations is correct is a matter of pure speculation. It is probably a combination of them all. A philosopher might focus on Schopenhauer, while more-sociable or even vain individuals might place more emphasis on the social aspects of the question. However, the question of what controls the brain’s development, who or what maps out the path of its plasticity, is one that concerns more than just music. We need to ask in general terms: who or what decides the way in which a brain develops?

The answer is: nobody. Except the brain itself. Which does not mean, however, that anything is predetermined. The brain is interested in achieving the effects it desires. It wants to accomplish, affect, set things in motion. However, what it wants to achieve is open. Although it is interested in what might be good for the brain, what that turns out to be depends on what the brain has learned. Initially, the brain is completely indifferent to everything going on in the outside world. This indifference only disperses once constant interaction with the environment teaches the brain what is important to it.

Depending on the nature of that environment and how the brain reacts to it, the resulting character may be egoistic or altruistic. It may be kind and affectionate or cruel and malicious. It may favour reproduction and survival of the species, but also pain and extermination. There are people who sacrifice their lives for others, and there are people who sacrifice others’ lives for their own. Initially, it’s all the same to the brain; in other words, each of these is just one of a myriad of possible objectives that could become a target for its interests and desires.

The extreme plasticity of the brain means that it may be aimless at first, taking a specific direction only later, in the course of a constant learning and memorisation process. So it is impossible to say that the brain necessarily serves the preservation of an individual human being, or, indeed, that of the whole human species of Homo sapiens; it is not automatically ‘biopositive’, to use a word coined by the German expressionist poet Gottfried Benn, and can take a different direction and even disengage from life altogether. Which, however, does not necessarily mean suicide — I will return to this ‘cessation of the will’ later.

For now, let me just note that there is nothing predetermined in the brain to tell it in which direction to develop. No morality, no biological self-preservation, no human interaction, and no God. It must find and learn about its own orientation — and the associative connections it makes, as well as pure chance, play a significant part in that process.

Character — or just habit?

Against this background of the brain’s plasticity and fundamental indifference, the question naturally arises of whether human beings can have a personality, that is, a consistent character, at all, as this seems to lead to an incongruity: if we recognise plasticity as the only stable characteristic of the brain, we exclude the possibility of an immutable character; and by ascribing a distinct character to humans or animals — which we do, even basing our entire social interaction and our day-to-day lives on this premise — we are stating that there is something that is immune to plasticity.

Interestingly enough, in studies of twins, it is those characteristics with a reputation for fickleness that often turn out to be particularly stable, while those said to be persistent frequently reveal themselves to be particularly unstable. Since the late 1970s, scientists at the University of Minnesota have been recording the differences and similarities between more than 100 pairs of fraternal and identical twins who were separated immediately after birth and subsequently knew nothing of their twin siblings. The researchers discovered that the greatest point of similarity — after intelligence — was their political orientation.6

A few pairs of twins included in the study were particularly remarkable. Such as: Jack Yufe and Oskar Stohr, who were born in 1933 and grew up in different step-families. Jack was raised by their Jewish father in Trinidad; Oskar was brought up by their Catholic mother in Bavaria. One twin went on to work on a kibbutz and become an officer in the Israeli navy; the other became a member of the Hitler Youth. There was an awkward reunion at the age of 21, after which neither thought it was a good idea to see the other again. Nonetheless, when the brothers met again in Minnesota at the age of 47, brought together by the twin study, they had no problem getting along with each other. On the contrary. A closer examination of their political views showed they were on the same wavelength in many areas, particularly in their espousal of conservative values and their categorical rejection of outsiders. In addition, Oskar immediately abandoned his anti-Semitic stance, and his brother never mentioned it to him again. Rather than arguing, they settled on another, common enemy: Cubans, and communists in general. From that time on, there were no differences of opinion between the two twins, who remained on good terms.

Of course, this shows that blood is somehow thicker than water; and that genes can create an undeniable degree of similarity. On the other hand, however, this example of twins also exposes a typical human fallacy: our tendency to interpret characteristics that change little, such as shyness, pedantry, and political conviction, as permanent character traits. But on closer inspection, it often turns out to be the case that they only appear so stable because they have not been exposed to any pressure to change from the environment, as no one ever made a serious attempt to change them.

Returning to the case of Oskar and Jack in this context: one twin developed anti-Semitic views because that was ‘the done thing’ in the fascist environment he grew up in and because he was never confronted with strongly held opposing views. His brother, by contrast, was given a strictly religious upbringing. Hardly anyone would have thought that the two ideologically so opposed brothers could even sit down together at the same table. However, in reality, Oskar renounced his anti-Semitic views in no time at all. He was not an irredeemable Jew-hater — it was just that during his development in Bavaria he never encountered anyone who might have put an end to his anti-Semitic tendencies; indeed, he was encouraged to nurture them. After meeting his brother, however, his brain was confronted with different stimuli, with the reality of his own Jewish heritage and twin brother — and Oskar took up a new political perspective, almost like putting on a new pair of underpants in the morning.

The brain simply wants to achieve the effects it desires — in Oskar’s case, ideological agreement with his twin brother — but, ultimately, it does not care how those effects come about. If he had grown up in an environment characterised by the liberal 1968 generation, it is perfectly possible that Oskar would have become a staunch communist, only to convert to capitalism if the brother he met again in Minnesota had become a business executive. If I have mastery of a musical instrument, I will want to play that instrument over and over again because that achieves the desired effect for me. Colloquially, we say it ‘gives us pleasure’. And it is actually irrelevant whether I derive that pleasure from the fact of my own virtuosity or from the fact that others are listening to me — all that’s important is the effect it achieves for me.

And the same is true of human character traits. If I am an extrovert, I will always tend to show that trait, because it results in a positive effect for me. By the same token, if I am an introvert, I will always tend to display that trait, because it results in a positive effect for me. The brain always does whatever will convey the best effect in the situation it finds itself in at any given time. If my extrovert behaviour goes down well with others, the result will be a positive feeling for me, and I will repeat that extrovert behaviour again and again — and the external and internal affirmation I receive will gradually turn me into an extrovert. Contrariwise, I will develop into an introvert if my introverted behaviour repeatedly results in positive effects. And if I annoy people with my extrovert behaviour, my outwardly oriented brain will switch down a gear and may possibly even adjust to introverted behaviour.

The supposedly immutable features of a personality are mostly just characteristics that are not influenced by stimuli for change and which can therefore easily be mistaken for being invariable. However, if and when a situation occurs in which the brain no longer achieves effects with that behaviour, it once again deploys its capacity for flexibility — and the supposed character collapses like a house of cards.

Can anyone be a henchman?

One of the scientists who recognised as early as the 1960s that personality is not exactly a reliable constant for evaluating human behaviour was the American psychologist Stanley Milgram. His previously mentioned experiment remains one of the most notorious and controversial psychological studies to this day.

In 1961, Milgram was 27 years old and working as a young researcher at Yale when he placed a newspaper ad: ‘Persons Needed for a Study of Memory … Each person who participates will be paid $4.00 (plus 50c carfare) for approximately 1 hour’s time.’ Participants were paid in advance and were told they would be able to keep the money, no matter how the experiment ended. Milgram then told participants that the experiment would investigate some pedagogical aspects of learning, which, like the newspaper advertisement, was a lie. In reality, the trial was a test of obedience.

The participants were seated before a bank of 30 switches arranged in such a way as to deliver ever-increasing electric shocks to another person, who was strapped into a chair in another room. The switches on the shock generator were marked from 15 volts to 450 volts. The volunteers were then told to ‘teach’ a list of — mostly meaningless — word pairs to the person in the next room by reading them aloud so that the person could memorise and repeat them. The experimenter instructed the volunteers to administer an electric shock to the learner every time he made a mistake, with the voltage increasing incrementally each time. Via a speaker system, volunteers were able to hear the reactions of the unseen learner in the next room. And that reaction was shocking, since the ‘learner’ strapped into the chair was in fact an actor trained to give the same pattern of reactions for each volunteer ‘teacher’ when they appeared — the shock generator was just a dummy machine! — to give him an electric shock: demanding to be released from the experiment when the shocks reached 150 volts, screaming in pain and warning he had a ‘heart condition’ when the voltage reached 240, and remaining dead silent after 315 volts, leaving his supposed torturer and relentless punisher with the impression that the electric shocks they are administering were now simply causing an unconscious body to jolt.

Milgram found more than a hundred volunteer subjects for his experiment. And 65 per cent of those continued the shocks all the way up to 450 volts! Even though the man in the adjoining room was screaming with pain and they must have thought that he was unconscious by the end. Furthermore, they activated the switches although no one was forcing them to do so. The experimenter, who was with them in the room, simply repeated dispassionately that the shocks would ‘result in no permanent physical damage’ and that ‘the experiment requires that you continue’. Nothing more.

Milgram’s experiment caused an earthquake in the world of psychological study, since it showed that the level of obedience to authority of someone like Adolf Eichmann is no exception, and that it is not even necessary to exert very much pressure on a considerable majority of human beings to render them so compliant that they are willing to torment and even kill innocent people. All normal people could become torturers and murderers if they found themselves in a situation where torture and murder were permitted or supposedly served a ‘higher cause’. Milgram produced empirical evidence of the ‘banality of evil’, which Hannah Arendt had described in her book about Eichmann’s trial in Israel. Henceforth, no one could any longer claim that he or she would never have collaborated with the Nazis under any circumstances.

However, the question that most concerned Milgram was whether those who turned the shock generator up to 450 volts differed in their personality structure from those who refused to comply with the experiment all the way to the bitter end. To investigate this, he invited the volunteers back, and this time subjected them to comprehensive personality tests. Milgram died early of a heart attack in 1984, but his former collaborator, Alan Elms, later reminisced that the results were absolutely disappointing: ‘Catholics were more obedient than Jews … The longer one’s military service, the more obedience … Many of these findings “washed out” when further experimental conditions were added in …’ Typical characteristics like impulsiveness, extroversion, empathy, and moral sensitivity did not have any special significance. ‘In fact I didn’t get significant differences on any of the twelve standard scales [for personality traits]’, Elms says in summary.

This does not mean that there is no such thing as personality in general. But Milgram’s studies show that the given situation also plays an important a part in behaviour, and in some cases it is the deciding factor. What’s more, the fact that Catholics and those with long military careers were particularly obedient confirms that this apparently stable character trait was so strongly developed in those individuals because they had not been encouraged to overcome their obedience, but rather their obedient tendencies had been constantly reinforced. If a brain repeatedly experiences positive effects as a result of obedience — for example in a Catholic or military environment — it will also be more inclined to obedience in the laboratory setting, and send a signal to a finger to activate a switch that will administer an electric shock to a fellow human being. This is because it is real experiences and successes, as well as punishment and disappointments, rather than abstract principles and norms, which shape the brain and can continue to reshape it.

I am fully aware that this may be unwelcome or unacceptable news for those who are convinced that individuals make decisions consistently and freely. But I would like to stress that the news is not actually bad at all. The enormous plasticity of the brain also means that we can learn to live with situations that we commonly consider unbearable, and can even reshape them into sources of incomparable and unexpected happiness.