3

The Coming Out of Locked-in Patients

how the brain gives a voice to the voiceless

There is little that stretches our powers of imagination more than the fate of patients with locked-in syndrome, whose brains are strangely detached from the rest of their body because nerve signals can no longer reach their muscles. That means they are condemned to total paralysis. Not only can they no longer walk, grasp, eat, drink, or go the toilet, but also all their channels of communication are cut. Speaking, facial expressions, and physical gestures are all impossible without the use of muscles. Patients with total locked-in syndrome are not even able to use eye movements to communicate with their surroundings. What remains for them?

The Swiss philosopher Ludwig Hohl spent many years living in a dingy basement flat, misunderstood and sometimes even unnoticed by those around him. That is far removed from the fate of a locked-in patient, but it was enough to lead the isolated poet to the insight that ‘once the ability to communicate is gone, life is over’. This encapsulates the feeling most of us have when we think about an absolute inability to communicate: that it means the end of everything. Over and done! After all, humans are not trees or grass plants. We are creatures with a powerful need to communicate; we want to talk or engage in exchanges with others in some way; we want to reveal our thoughts and show others that we are who we are. But all that is impossible for those who are trapped in a completely paralysed body.

What can locked-in syndrome mean, then, other than a kind of living death, which simply requires the life-support machines to be switched off to finish the process in the hereafter?

Can a life in a state of senselessness make sense?

The fact is that locked-in syndrome is far from a kind of death before death. To understand this, it is necessary put yourself in the place of the locked-in patient — that is, to imagine the unimaginable. This involves casting off preconceived ideas about the way this situation comes about. For example, that it comes all of a sudden. In fact, it is usually a gradual process, unnoticed at first, later becoming more obvious and increasing irreversible. Rather than spontaneous strokes leading to complete paralysis, it is more often caused by diseases that take years or even decades to develop, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), multiple sclerosis (MS), and Parkinson’s disease. On the one hand, this means that the grim developments slowly build up and hopes of improvement are repeatedly quashed by the body’s increasing process of deterioration; on the other hand, it also means that patients have time to grow accustomed to their future. Of course, this means getting used to a catastrophic fate, but that is still different to being overcome by it without warning.

When all muscle activity ceases, patients are left lying motionless in bed, dependent on a ventilator and a feeding tube. The patient’s mucous membranes dry out unless they are artificially moistened. Their eyes are closed, and if someone opens them, they see only shadows at best, as their corneas dry out over the years. Their sense of touch is similarly atrophied by years spent without grasping anything and lying in the same position. This means patients literally lose skin contact with the world. Often, they can barely feel when others touch them. On the plus side, this often means they also no longer feel any pain.

However, their ears remain functional; locked-in patients can still hear. This means they are aware when doctors and relatives — thinking the patient lying in front of them with their eyes closed is in a constant, unconscious state of sleep — thoughtlessly debate switching off their life-support machines in their presence.

Research carried out by my collaborator Boris Kotchoubey shows a third of patients thought to be in a persistent vegetative state — that is, without conscious awareness due to massive damage to the cerebral cortex — are in fact trapped in a locked-in state with an almost fully or even completely functioning and receptive cerebral cortex.7 Kotchoubey examined more than 100 patients in Germany, and our cooperation partners in Belgium reached a similar conclusion in their study of 100 patients. This means we must assume that in my own country alone, in Germany, there are some 3,000 people lying motionless in hospital beds who are being treated as if they were unaware of what is going on around them, although they are conscious and in possession of their perceptive faculties! Many of them are forced to listen to conversations about turning off their life-support systems. Even Franz Kafka could not have conceived of a more nightmarish scenario.

Or are locked-in patients perhaps not so aware of their surroundings after all? Even if their sense of hearing still works, they are unable to react to what they hear. And if a brain can no longer achieve the effects it desires, it stands to reason that it will begin to shut down and eventually no longer consciously register the stimuli it receives from the senses. Could it not be the case that locked-in patients and those in a persistent vegetative state are actually quite similar? And that the world has not only lost them, but they have also lost the world?

First contact

Silence. The first thing you notice when you enter a locked-in patient’s room is the silence, broken only by the regular hiss of the artificial-ventilation machine. It is not like an intensive-care unit, where the atmosphere is dominated by constant coming and going, and the beeping of life-support machines and monitoring devices. Locked-in patients lie in bed apparently as stiff as a corpse, as if they had already shuffled off this mortal coil. And that’s why we feel afraid as we approach one’s bed.

But we approach, in spite of our fear, because the human being lying there is the person we laughed, joked, ate, and chatted with just a few years before. We take the person’s hand — and then comes the surprise. That hand, which appears so pale and lifeless, is soft and warm. The room is still quiet, we still hear nothing but the hissing of the ventilation machine, but now we know: there is life here; warm, pulsating life. And perhaps this person would feel better if we broke the silence a little. Not by just talking about them as if they were lost forever, and not by reducing them to just a body that might need to be moved to another bed. But by speaking to them, making contact with them as an important part of our life, worthy of respect, as we used to in the past. After all, that warm, soft hand can’t lie. It alone is evidence that we are not confronted with a half-dead human, but with someone who is still fully alive, and not only that, but with someone who we want to be involved in our lives? Right?

In an attempt in Tübingen to find out how locked-in patients experience the world, and to learn more about their psychological state, we began by examining their brain activity by means of a classic EEG (electroencephalogram). Sensors are placed on patients’ scalps to measure the voltage fluctuations in their brains. We then confront them with various tasks and training programs. For example, letting them hear different sequences of letters of the alphabet. As soon as patients hear the letter they want to say, there is an increase in brain activity, which causes a computer to record the relevant sound. In this way, it is entirely possible to put together complete words using the answers from the patients’ brains.

Another method consists of training patients in neurofeedback techniques in which they learn to control their own brain activity in order to pick out the desired letters. After hearing a prompt signal, they create the appropriate brainwaves by activating specific thoughts or emotions. Many people imagine making a movement and thereby create a frequency of more than 20 hertz (cycles per second) in the areas of the brain responsible for movement. Others stimulate a frequency of 8–13 hertz in the same brain regions by imagining stillness. At the same time, an audio signal increases or decreases in volume to allow them to monitor whether their brain activity is increasing or decreasing during these acts of concentration. When they succeed in increasing their brain activity at the appropriate time, they are rewarded by the computer (‘Well done!’). In this way, they learn — albeit after many hours of practice — to stimulate the desired brainwave frequency alone and this allows them to select letters from a list as it is slowly read out to them, which are then repeated aloud by the computer to inform them of the result and give them a chance to correct it if it is wrong. The advantage of this method is that it does not require any muscle activity, speech, or eye movements; rather, communication takes place via a so-called brain–machine interface (BMI). This should be ideal for patients with total locked-in syndrome.

However, despite the success of this method with healthy volunteers and with locked-in patients who still have the ability to move their eyes, when we attempted it with totally locked-in patients the results were crushing. There was no indication that those patients retained any conscious awareness, let alone an ability to communicate. However, a classic EEG works using electrodes placed on the outside of the skull. That is, at a distance from the brain, not to mention the fact that the cranium does not let all electrical impulses through.

Therefore, we decided to use a different, much more informative method, in which the sensing electrodes are placed in numerous locations within the brain itself. We initially planned to perform the operation on two patients, but this confronted us with an ethical dilemma: who should make the decision about such a massive intervention when the patients themselves could — presumably — understand everything going on around them, but were unable to communicate?

Legalistically, the answer appears to be clear: the decision is incumbent on the court-appointed guardian of the patient, usually a family member, but in some cases it is the guardianship judge him- or herself. When such guardians provide written permission, the brain operation can go ahead since it counts as a medical emergency; and if the operation results in an improvement in the ability to communicate, the patient’s quality of life will also improve. But does the patients share this — unverified and speculative — view? There is really no way to tell, since the very aim of the operation is to allow the currently non-communicative patient to ‘talk’. Non-linguistic techniques have to be found to allow patients to express their consent or refusal.

One way is to use the mucous membrane of the mouth. We chose this method to ask the consent of a totally paralysed patient whose guardianship judge and husband had already given their consent — albeit hesitantly. We asked her to imagine drinking a glass of milk if her answer to our question was ‘yes’, and to visualise drinking lemon juice if the answer was ‘no’. By measuring the acid content of the mucus in her mouth, we were able to ascertain whether she was signalling ‘yes’ or ‘no’. If the pH value sank (more acidic), the answer was ‘no’, if it rose (more alkaline), the answer was ‘yes’. We then informed the patient of the risks and possibilities associated with implanting electrodes in the brain and asked her if we could perform the operation. The mucus in her mouth signalled her consent. We repeated the question several times over the next two days and her answer remained the same. Of course, we still had our doubts, since the pH level of mucus is not the same as a spoken or written word. I spent many a sleepless night worrying about this, but eventually we decided to perform the operation.

In the case of the second patient, our decision was made easier by the fact that he was able to give his consent before he slipped into his totally locked-in state.

Neurosurgeons from the University of Tübingen then implanted electrodes in the brains of both patients. Subsequently, whenever one of these contacts showed increased activity in a desired region of the brain, we rewarded the patient, for example by encouraging them verbally. In this way, we ‘seduced’ them into repeatedly activating certain areas of the brain in expectation of a reward. The aim of this positive reinforcement was to turn random neuronal activity into deliberate activity controlled by the patient. We were already imagining playing recordings of spoken letters or sequences of letters to patients so that they could select the ones they intended by activating a certain area of their brain, which we would measure with our instruments. It is easy to imagine how long it takes to piece together a word or even an entire sentence using this procedure. But the concept of patience acquires a whole new meaning when you are working with locked-in patients.

And that patience is not always rewarded. We had one patient who appeared to provide purposeful yes-or-no answers to our questions. She was able to confirm the names of her children and the profession she had learned. We then went one step further and asked her questions to which we did not already know the answers. For instance, whether we should change the position she was lying in, or whether we could implant more electrodes in her brain — which she answered in the affirmative. However, over the next few weeks, all logic disappeared from her brain signals. Her yeses and noes changed as randomly as flipping a coin.

Communication was more reliable with another patient, George, who was a former soldier. However, he had had the opportunity to learn the brain language to some extent while still able to use his eyes to see. He was able to recognise a change in colour on a computer screen, or see a point moving up or down as he managed to activate certain areas of his brain. The way he managed this, what exactly he thought of to achieve it, was left up to him without any interference from us. We adhere to this principle of non-interference when using the brain–machine interface to this day. As the saying goes, thoughts are free — and why should that principle not hold for locked-in patients in particular, who consist almost exclusively of thoughts?

Another advantage for our still-sighted former soldier was that he could give conformation using eye movements, whenever we were unsure about his brain signals: ‘Did you mean “yes”?’ If he raised his eyes, as we had agreed with him earlier, that meant we were correct.

However, at some point, his eyes fell shut and he was left optically and communicatively in the dark. Just like the female patient mentioned earlier, his yeses and noes were now purely random. We made another attempt to improve communication with him by also implanting electrodes within his brain, but the results remained disappointing. Not just for us, but also for his carers and family members, who had hoped they would soon be able to communicate with him again.

Where there’s a will…?

These results, then, appeared to show that totally locked-in patients no longer have any interest in the outside world. And that would be a logical conclusion, since all movement — and thinking is ultimately nothing other than a form of movement! — aims to achieve an effect.

When a baby cries and realises that this prompts a rapid response from its parents, it will include crying permanently in its repertoire of behaviours. If, by contrast, no one responds, crying will disappear as a behaviour pattern. When we close our hand around a glass we, literally, get a grip on it; if that were no longer to be the case, our brain would no longer issue instructions to that end and our hand would remain motionless. No effect, no action. Thus, it would be perfectly absurd to hope that locked-in patients could communicate with us over the long term when their brains are no longer able to make anything happen.

An electronic ‘caress’ to the reward centre of the brain may be nice, but it is no substitution for a real effect. Locked-in patients may still be able to fantasise and wallow in the memories stored in their intact cerebral cortex, but their capacity for intentional thinking becomes paralysed. Their will is snuffed out — and with that, they are no longer what we would generally consider an animate individual. Such were my thoughts, at least, at that time.

However, I was not ready to give up yet. I was plagued by the unbearable thought that these people might still yearn to communicate. I was also loath to disappoint the patients’ families, who had a deep desire to have contact with their loved ones and who were also unwilling to abandon all hope. After much head scratching, I hit on another method. The electrical processes of the brain had proven difficult to control. But what if we took a different approach to the BMI, and used changes in blood flow, which we could measure with near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), rather than electrical impulses, to allow the brain to speak?

The ‘communication advantage’ of blood flow lies in the fact that there are receptors and sensory organs for it in the blood vessels. Patients are able to perceive where their blood is flowing with higher or lower pressure. Even in the brain. We can feel changes in the metabolic activity and the associated blood flow. We may not be able to put it into words as we would describe something we see or hear, but we register it nonetheless. This is in stark contrast to the core business of the brain, electricity, which we cannot feel, because we lack the necessary receptors for it. Which also makes sense. Just imagine if every thought we had caused a different physical sensation, perhaps even pain! Our brain would then be completely trapped inside itself, permanently occupied with thinking and the sensations that thinking caused. It would get caught up in an endless, senseless cascade of thoughts and feelings, which would presumably overwhelm us. Evolution has therefore left us without such receptors and provided us instead with a feeling for blood flow in the brain. That’s why this appeared to be more promising than an EEG as a way of enabling our patients to speak. But would it really work?

We were all eager to find out and keen to put it to the test. So we launched another study with a totally locked-in patient. And indeed, after just a few days, she began to make contact with us via the blood flow in her brain! This, despite the fact that for months she had managed to communicate with us only very rarely via her brainwaves. We asked her yes/no questions, such as whether she would like a visit from her children, and she sent blood flowing to a particular area of her frontal lobe to signal a ‘yes’. We then reworded the questions, so that the same meaning required a negative answer, and the patient had to change her original answers around. This was to make sure that there was no chance element to her responses. Our patient gave the expected responses, changing from ‘yes’ to ‘no’ and from ‘no’ to ‘yes’. Not always, but with a certainty of more than 70 per cent over the course of many days — therefore with a much higher certainty than the 50 per cent probability that a tossed coin will come up heads.

When the question was sufficiently important to her, the patient achieved a quota of 100 per cent. Once, she developed bedsores due to a lack of attention by her carers, and we asked her in several ways whether she was in pain. The blood flow in her brain signalled a clear ‘yes’. When her bedsores had healed, we asked her, again in several different ways, whether she was still in pain. Her answers were a clear ‘no’. When the stimuli were sufficiently intense — which is of course so in the case of pain — and affected her essential, vital interests, the patient was fully with us. It was possible to communicate with her more reliably than with some people who are in full possession of their communicative faculties.

This was a great success, even if successes in the scientific world are never as sudden and overwhelming and euphoric as they are on the football pitch when goals are scored. In science, they are always connected with doubt. The central question is always whether the results of an experiment can be reproduced, whether they are consistent, or whether they are just a fluke. Furthermore, the interpretation of those results could have been influenced by the researchers’ anxious expectation, making them a victim of the infamous confirmation bias. This explains why scientists rarely experience feelings of triumph.

By contrast, every day and every question successfully answered by patients fills their loved ones with more relief and joy that they are ‘still there’ and do not appear to be in a desperate situation. And, of course, even scientific researchers are not left cold by such reactions.

Our patients could communicate! They could open up to us. They could influence their environment in order to bring about an improvement in their physical comfort. There seemed now to be no doubt: the will of a locked-in patient may weaken, but it does not disappear. And why should it? After all, these people are usually adults whose will has ingrained itself in their brain over the years and neurologically stabilised itself so strongly there that it cannot simply be snuffed out. This would be different in the case of a small child whose will is still only weakly anchored in its brain and would indeed be snuffed out if the child were to fall into a locked-in state. But in adults, it remains more or less in place.

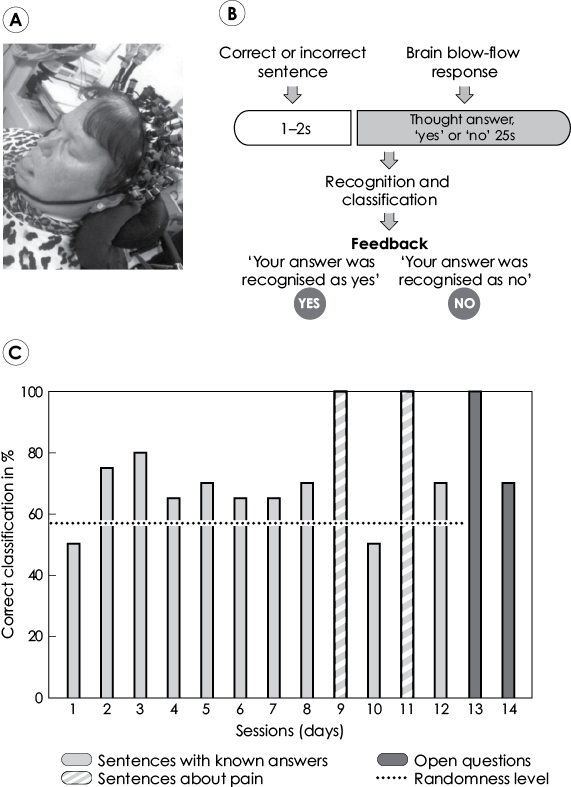

The locked-in patient Waltraud Faehnrich working on the brain–machine interface (BMI)

(A) The patient suffers from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). She is fed and ventilated artificially; all her muscles, including her eye muscles, are paralysed. The photo shows her with sensors attached to measure the blood flow in her brain with infrared light (near-infrared spectroscopy, NIRS).

(B) Experiment design for questions in which the key word or phrase (e.g. ‘quality of life’ or ‘pain’) is at the end of the question. This last word or phrase takes one to two seconds to say, after which the patient has 25 seconds’ time in which the think the answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’. This is then followed by feedback from the computer, ‘Your answer was recognised as yes (or no)’.

(C) The chart shows recognition levels of the brain–machine interface (BMI) over 14 days. For general questions to which we already knew the answers, the accuracy of the answers generated by the BMI was about 10 per cent above the random level. Accuracy was significantly higher for questions relating to pain, and open questions. On day 9, the patient was in severe pain and answered ‘yes’ with 100 per cent accuracy to the question ‘Are you in pain?’ On day 11, she was no longer in pain and she answered ‘no’ with 100 per cent accuracy. The final two bars on the chart show her answers to open questions (‘Are you happy to be alive?’, 100 per cent ‘yes’).

This has nothing to do with any concept of Homo sapiens being metaphysically equipped with an immortal will. It has to do rather with a fundamental fact about the brain: it never loses anything, but is constantly modifying and rewriting what it has learned. Once something’s there, it’s there forever — and this is particularly true of our will, which develops over many decades and becomes one of the driving forces of our lives.

However, the will does need to be tracked down and loosened up to make it visible. And this is, of course, a challenge to those around the patient. It requires a great degree of sensitivity. When family members, carers, and doctors are not capable of such sensitivity and simply write the patient off, the patient’s will is destined to go unrecognised.

Attention is everything

To establish contact with totally or almost totally locked-in patients, the first thing is to find out whether they are aware. When they are dozing or sleeping, it is just as impossible to communicate with them as with healthy subjects. But when do locked-in patients sleep? Their external appearance offers no indication in this respect, since their eyes are always closed and their bodies still, the only little movement caused by rhythmical wheezing of the ventilation machine as it pumps oxygen through a hole in the patient’s trachea.

Luckily, an ordinary EEG can provide more information on the waking state of such patients. And this shows us that their normal day-night rhythm has often ceased. This is not surprising, since it is no longer of any use to them. Instead, their sleeping patterns become rather chaotic. Extended periods of dormancy alternate with shorter periods of heightened awareness, which mostly do not coincide with our own — locked-in patients’ periods of productive wakefulness often occur between three and five o’clock in the morning, which poses a considerable problem for researchers, who naturally prefer to work during the day and sleep at night. Not to mention the fact that even for a healthy individual who is interested in the subject matter, continuing a conversation by pressing a button, with just yes/no answers and without the aid of gestures and facial expressions or the written word, can be a rather tedious activity. Those who wish to communicate with locked-in patients must adapt to them and their particular rhythms and means of communication — and that is not easy.

This is where the patients’ family members come into play, since they are ultimately the ones who can open a window on the patients’ life or close it forever. The patient described earlier was lucky that her husband never left her side. He also never asked us to stop the experiments we were carrying out with his wife, seeing them rather as a chance to re-establish contact with her — a chance he intended to seize, whatever the nature of that contact might turn out to be. He learned to use the BMI so that he could communicate with his wife without outside help. Most locked-in patients are never given such a chance, since their doctors and their relatives dismiss them as hopeless cases who can only be granted a dignified end. And it is true that if nobody engages with locked-in patients, their situation does indeed become hopeless and without prospects for the future, since they have no positive experiences and no means of communicating. The premise that they should not be made to suffer unnecessarily long then becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

In a different case, we were helped in gaining a patient’s attention by her husband. The couple had been married for many years and they knew each other better than anyone else. And so he aroused her attention by stimulating her nipples. He was also able to tell by the state of his wife’s nipples, whether his wife was responsive to speech. Thus, he would gently wake her by stimulating her nipples and developed a very precise feeling for when she was awake and receptive. None of our modern, high-tech instruments were able to provide this information nearly as accurately as the patient’s husband.

Many people find such erotic stimulation of a defenceless patient disconcerting or even appalling. But physical contact is a stimulus that can still reach totally paralysed patients, allowing them to feel themselves and the presence of another person. Loving family members can provide pleasant sensations for patients by caressing them, which strengthens their connection to life and helps keep them in the world of the living. It goes without saying that we need to be certain that a patient wants to be touched by the person touching her and the normal rules of intimacy must be preserved — a woman would be more likely to experience stimulation by a random carer or doctor as an act of rape, and may not be in a position to enjoy such stimulation by her husband if carers or doctors are present and watching.

With those provisos, we usually encourage the family members of locked-in patients to stroke, caress, and massage their loved ones. After all, wouldn’t it be far more terrible to deny totally locked-in patients the opportunity to rediscover this means of access to the world and to their own libido?

The return of Ariel Sharon

Even for patients in a persistent vegetative state, there can be a doorway into the inner world of their existence. It just requires someone willing to take to the trouble to open it. This is strikingly demonstrated by the example of Ariel Sharon, who died in January 2014 after eight years in a coma.

The Israeli prime minister had suffered a stroke in December 2005, resulting in several operations on his brain. An EEG showed activity in his cerebral cortex, but the stroke had caused serious damage. At that time, Sharon’s doctors predicted that the 78-year-old would not regain consciousness. In April, now in a persistent vegetative state, Sharon was moved to the Sheba Medical Centre, near Tel Aviv. He was still able to breath unassisted, but that was about all. His son Gilad wrote, ‘He lies in bed, looking like the lord of the manor, sleeping tranquilly … When he’s awake, he looks out with a penetrating stare.’ He was fed through a tube — and showed no response to his environment.

As early as the beginning of 2006, doctors advised Sharon’s family to let the former prime minister die. Based on the computed-tomography (CT) scan, the doctors were basically saying, the game was over. But Sharon’s two sons insisted their father should be kept alive. He was visited every day by family members, his sons, his daughters-in-law, and his grandchildren. They spoke to him, caressed him, held his hand, or just chatted among themselves, eating home-made food so the aromas would reach his nose. They shaved him, dabbed him with his favourite cologne, let the children play noisily in his presence, sang him songs, and played the instruments they were learning to him — indeed, his hospital room was a busy place throughout the day. At some point, Gilad had the impression that his father was looking at him and even moved a finger when Gilad spoke to him. Or was it just his imagination, wishful thinking rather than reality?

In early 2013, the neuroscientists Alon Friedman (Ben-Gurion University) and Martin Monti (University of California, Los Angeles) carried out some tests on their famous coma patient. They played him recordings of his sons’ voices and exposed him to various kinds of tactile stimuli — and observed the way his brain reacted, using magnetic-resonance imaging. Those scans showed: Sharon was reacting. Not always, but often. Which of course did not say anything about his state of consciousness. Nor did it say anything about his prospects for the future. But there was no doubt that Sharon’s brain was displaying recognition abilities that his doctors had pronounced impossible almost seven years earlier.

Perhaps they had misinterpreted the scan images back then. Or, perhaps Sharon’s brain had recovered, at least to the extent that was just possible despite the enormous damage it had suffered. With all the commotion around him in his hospital room, his brain never had the chance to degenerate completely and depart from the world forever. Instead, it was repeatedly challenged and confronted with stimuli — and since all the commotion was more or less focused on Sharon, his brain was also able to observe effects. Under such conditions, a brain does not usually switch itself off. Rather, it tries to make use of the resources it still possesses, to play the card of its enormous capacity for plasticity.

This is also borne out by our experiences with 100 patients whose condition had been diagnosed as a permanent vegetative state. We identified 30 whose brains were shown by MRI or by EEG to retain significant reactivity to the type of cognitive tests also given to Sharon. I will never forget the way one patient suddenly opened his eyes and stared at me quizzically. After five years of lying impassively in bed! This was a patient from Israel, and, after waking up, he was even able to tell of the ordeal he had suffered in the Nazi concentration camps. His doctors and his family had already requested several times that he should no longer be tube-fed and allowed to die. However, their requests had been denied, since Israel is extremely cautious about euthanasia, due to religious considerations and the terrible events of the Holocaust. This prevented him from being sent from a supposedly irreversible vegetative state into a state that would have been truly irreversible.