6

Brutal Confrontation

controlling anxiety and depression without medication

Most spiders are perfectly harmless. Even most kinds of the dreaded tarantula are safe, and those that are native to Europe are not even able to pierce human skin with their fangs. Only the bite of the European yellow sac spider can sometimes be painful, but no more than a bee or wasp sting, and, unlike those wounds, the bite of the yellow sac spider has very rarely been known to cause allergic reactions. Not to mention the fact that it is extremely unusual to come across one of these rare, timid, nocturnal spiders. To summarise: where I live, there is actually no reason to be afraid of spiders. Cars, cigarettes, and even electric toasters pose a far greater threat to Europeans than do spiders.*

[* Even in parts of the world with dangerous spiders, the danger of spiders in general is greatly overstated, e.g. there’s no need to fear the basically harmless huntsman or much-maligned white-tailed spider in Australia.]

Nevertheless, up to 10 per cent of people in Germany suffer from arachnophobia — fear of spiders. Nine out of ten of those people are women. But why does this phobia even exist, when spiders are so harmless? Some psychologists believe the more dissimilar an animal is to humans in appearance, the more common and the more extreme phobias of it will be. However, sticklebacks and tree frogs are hardly similar to human beings, and they don’t provoke fear in anyone. Another explanation is based on the argument that it is the unpredictable way arachnids move that frightens people. Along with their apparent ability to appear suddenly as if from nowhere. But most arachnophobes will scream just from catching sight of a spider waiting motionless in its web beneath a bridge, in full view of any passers-by.

Is it because at some time during the evolution of Homo sapiens, an idea that any hard-bodied creepy-crawly is a potential source of danger was programmed into our ‘primal knowledge’? After all, thousands of people die from scorpion bites every year in Africa and Asia. In fact, however, arachnophobia is much less common in those regions than Europe, where there are no scorpions at all. So why should evolution have allowed Europeans the luxury of a phobia of something that does not even exist here, and presumably never did throughout the history of human occupation of this geographical area? And why should evolution have ‘blessed’ almost exclusively women with that fear, although they are no more likely to encounter a dangerous arachnid than their male peers?

For us, a phobia of cars or nuclear power plants would make much more sense, but if you show people from industrialised nations pictures of those objects, they tend not to show a strong emotional reaction: for example, there is no significant reaction in their thalamus — a very primal, from an evolutionary point of view, part of the brain, involved in relaying information about potential threats to the cerebrum. This lack of reaction is presumably because such modern potential dangers as motor vehicles and atomic power stations were not yet in existence when the brain evolved and because, especially in the case of automobiles, we have become used to them as a normal part of our daily lives and are desensitised to their dangers.

Yet this is not the case for spiders. Many people, even those who do not suffer from arachnophobia, will often react rapidly and violently to an object before they are even consciously aware of its presence. However, that is precisely why such a fear is as senseless as a compulsion to wash one’s hands 30 times a day out of a fear of germs. And just as senseless as Pablo Picasso’s habit of insisting that his family — including two restless young children — sit quietly together in a room for a minute’s silence before any outing, because he feared something terrible might happen otherwise.

As understandable as it is, even post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) — following an accident, an experience of war, a severe illness, or a serious crime — is not rational. When someone is too afraid to ride a bicycle after an accident, or when a war veteran panics at the sound of sirens or aeroplane engines, we can understand their behaviour, but it does not serve any purpose for us or the person affected. If a big dog is bearing down on you and gnashing its teeth, it makes sense to run away in fear; if it is peacetime and you still scurry under a table in fear every time you hear a fire engine’s siren go off — and you even know that your reaction is out of all proportion — you have a problem. And it is, in fact, a communication problem.

You can tell an arachnophobe as many times as you like that spiders are not dangerous, and she can repeat it to herself like a mantra until she’s blue in the face — but that will not alleviate her fear. A concentration-camp survivor can assure himself a hundred times that he no longer faces torture and execution, but that will not stop him dreaming of it every night and panicking when he sees film footage from that time. The central problem with anxiety disorder is that sufferers — or more accurately, their conscious mind and conscious will — do not have access to the deeper areas of the brain where their fear originates. That access is interrupted due to a weakening of the anatomical connections between brain cells. It’s a breakdown of communication between neighbours, so to speak, who should be working together inside the skull, but who — for various reasons — have ceased to do so. However, that situation need not be a permanent one.

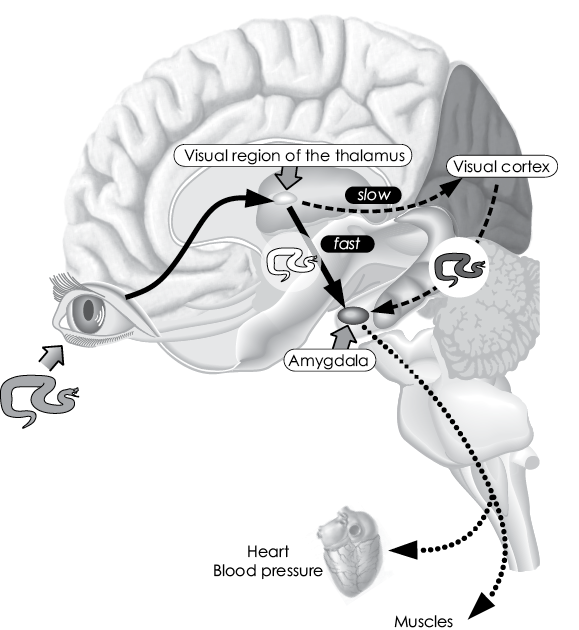

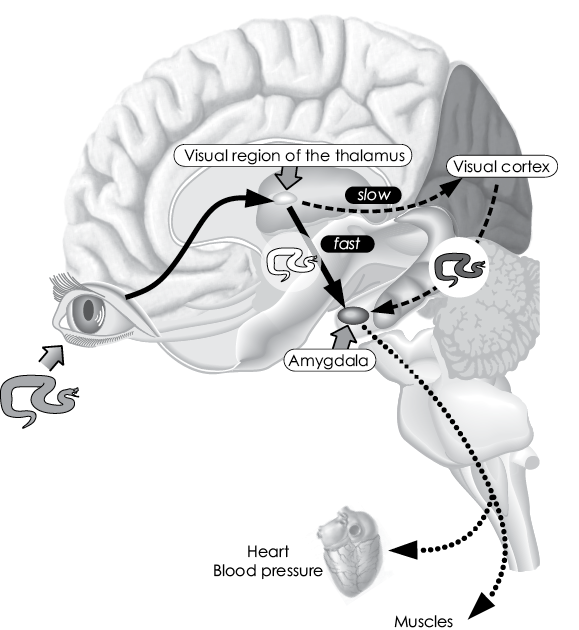

Development of fear, anxiety, and avoidance within the brain

A simplified illustration of the nerve signal pathways from the eye to the brain and the body, using the example of seeing a dangerous snake. First, the visual information is relayed within a few milliseconds to the visual region of the thalamus (arrow from eye to brain), which triggers an initial, unconscious pre-processing of the perception and relays a rough copy of the perception ‘snake’ to the amygdala (bold black arrow), which activates the relevant parts of the body (muscles, cardiovascular system) (dotted arrows) for fight or flight. This physical stimulation is fed back to the cerebrum (not shown here, for the sake of simplicity), and, a short time later (approximately 200 milliseconds), the visual cortex (dashed arrow from the thalamus) and the attached memory centres are activated — and only then is the person aware of the fear and its cause (dashed arrow to the amygdala).

Freud’s idea of fear — and the false conclusions he drew from it

If I were to name the greatest common denominator in brain science — which is no easy task for such a complex organ — then it would be ‘effect’. The brain wants to trigger effects, to initiate, to set things in motion, even without an ultimate aim. It wants to get rewards, pleasurable feelings; it wants dopamine and amphetamine. If the brain does not succeed in this, the areas that no longer achieve an effect and are no longer of any use are overwritten, and eventually wither away. Someone who had a couple of years of French at school but has never needed to use it will hardly be able to speak it in any useful sense at the age of 50. They might still be able to understand a word or two, but coming up with entire sentences will be a major challenge.

Our work with locked-in patients gave us a terribly haunting insight into the crucial role played in the workings of the brain by the expectation of effect. No longer having any access to their bodies, such patients are unable to achieve effects for themselves or anyone else, and that means their brains are in danger of descending into infinite indifference and lack of interest. Unless, that is, their brain can be convinced that it can still ‘bring it’, that it can still achieve effects. And, of course, some things are now possible that used to seem impossible, such as a totally paralysed man writing entire letters using only his own brainwaves.

In a way, anxiety disorders are the opposite problem. Take those people traumatised by war. Their panic response is totally disproportionate behaviour that does not achieve any meaningful effect. Quite the opposite, in fact: the war situation is over, and running screaming through your building will only cause disconcerted reactions in other people. Not to mention the fact that this behaviour renders the person concerned helpless and trapped by their own flight response.

That fear should be expected to disappear, since it achieves no sensible effect. But, in fact, the opposite happens, because there is a different, even more powerful effect involved! It may not be sensible, but it leads to positive consequences and thus a positive effect. The person concerned has no control over the senselessness of his or her panicked actions, but engaging in such flight and avoidance behaviour does bring relief from the deep-seated fear that’s causing them. These people ‘know’ cognitively that their behaviour is irrational, can repeat that credo many times, and may even be ashamed each time they end up under a table in a state of panic. But that knowledge is isolated in the upper regions of the cerebrum and never reaches the lower areas of the brain, where fear reigns supreme. What remains is the immediate effect of reducing that fear by means of the rapid flight reaction, and that effect is enough to maintain the irrational fear response.

Added to this is the fact the fear response inhibits other parts of the brain. The connections between the over-trained fear centres and those brain regions that regulate fear reactions are strengthened, but only in one direction: from the fear system to the regulating system. Connections going in the opposite directions atrophy and die away.

Even in his time, the Italian poet Dante highlighted in his work The Divine Comedy the powerful extent to which our fears are fed by our emotional unconscious mind. Sigmund Freud raised this insight to the central pillar of his theory of psychoanalysis. However, he drew the wrong therapeutic conclusion from it when he reduced the entire unconscious to memories of early sexual experiences or the parent–child relationship. And by maintaining that patients can be ‘talked out of’ their fears or trauma in psychotherapy — the success rate of this approach is extremely low, in particular for unconscious processes. It may happen that a phobia is eradicated during such a therapeutic conversation, but the usual effect is to strengthen it. It will only be weakened if the conversation leads to the emotional imagination deep in the brain being activated as violently as it was during the original traumatic experience, but without the much-feared effect occurring.

The brain needs to learn first-hand how it can overcome the fear in question without triggering a flight reaction, by directly experiencing the fact that there is nothing to flee from. So when a patient traumatised by experiences of war flees the psychotherapist’s practice in a panic and learns immediately from that experience that there is no actual danger and he can safely return to the therapist’s office, that experience — especially if it is repeated several times — may lead to the extremely well-ingrained fear mechanism in the brain being overwritten. The problem is that such extreme situations are difficult to bring about purely by talking. And when it happens, it usually happens by chance — and, as such, the phenomenon has nothing to do with systematic therapy or science.

Confrontation therapy, on the other hand, offers a prospect for treatment, which means ‘confrontation with the real impossibility of flight’. This may sound absurd, since an impossibility is something that doesn’t exist, but the meaning becomes clear on examination of a few examples.

Confrontation rather than conversation

Fate sometimes works in convoluted ways to make an idea seem credible even though it is nothing but an astonishing cascade of coincidences. This was the case with Horst, a patient who later became a good friend of mine. He was a jeweller by profession, and nothing untoward ever happened to him in the exercising of that profession. But it was a different story when he was driving. Horst had no less than five car accidents in succession and they all followed the same pattern: while he was overtaking a truck, the larger vehicle’s trailer suddenly swung out to the side and hit his car. After each collision, Horst’s car was overturned. Not once, but five times in succession, within just a few years; on two occasions, his car even caught fire and burned out!

After the fifth accident, Horst threw himself out the window of the hospital he had been taken to. He later described this himself as an act of attempted suicide, and it had considerable consequences for his life: in addition to the brain damage from the accident, he also suffered brain damage from the fall, leaving him lying immobile in bed, stiff as a board, and unable to react in any way.

His doctor at the hospital diagnosed an organic brain syndrome with mutism. ‘Mutism’ describes a condition in which patients are able to perceive and comprehend their environment normally, but for some reason do not ‘want’ to react to it. Thus, this is different to the condition of locked-in patients, who want to communicate but cannot. The doctor’s diagnosis of Horst’s condition was certainly the most obvious one, since he had suffered various brain injuries and he barely uttered a sound.

Yet this medic was sceptical. Somehow, Horst did not resemble someone whose brain was irreparably damaged. Rather, he gave the impression of someone who had retreated into a kind of cocoon. The doctor researched his patient’s background and discovered the incredible series of accidents he had suffered, which would easily have been enough to trigger a severe case of post-traumatic trauma and cause shock-induced paralysis. This meant the original diagnosis of irreparable brain damage might be wrong; indeed, the indications were that all was not lost for Horst. And so that scrupulous and self-questioning doctor referred his patient to my institute in Tübingen.

I did some more research into the jeweller’s former life, and became convinced that his condition was due to trauma. He had not only experienced those five serious car accidents, but also — at that time of complete helplessness — been terribly hurt by his wife. She had realised that the death or disablement of her husband meant full possession of their house would pass to her, so she took advantage of his complete helplessness and confined him to the cellar. During one of the panic attacks that caused Horst to rattle wildly at the door of his basement prison and then slump weeping to the floor, she kicked him in the head with her stiletto-heeled shoe. Her aim was presumably either to kill him outright, or to injure him so badly that a legal battle between the two over possession of the house would no longer be possible on his part.

During the ensuing court case and therapy sessions, she described the stiletto incident as an act of self-defence during a marital dispute, although anatomical examination of Horst’s injuries appeared to show otherwise. Eventually, possession of the house was awarded to Horst, but lawyers were not able prove a charge of attempted murder against his wife. Thus, he won a partial victory at court, but in the process his brain had suffered yet another injury, which presumably, in combination with his previous injuries, led to the severe memory disorders he suffers to this day.

Worse than those organic brain injuries, however, was the fact that the series of accidents he had suffered appeared to have left him with a — literally — paralysing fear, which we now needed to treat. We were aware that Horst had already tried almost everything, including psychotherapy, physiotherapy, and treatment with psychoactive drugs such as benzodiazepines (Valium), antidepressants, antipsychotics, and opiates. He had even tried homeopathic globules. But none of these had worked.

This was reason enough to try a completely different strategy, based on a phenomenon described by Ivan Pavlov in the context of his research into the psychology of learning. This is extinction — the phenomenon in which a conditioned behaviour is prevented by means of repeated confrontation without the possibility of avoidance. This kind of therapy may seem shocking and even inhumane, but if it can save lives or return them to normal, it should be used — as long as it is used properly.

So, I strapped the motionless Horst into my Mercedes and drove off with him. We jumped red lights, overtook without indicating, executed emergency stops until the tyres squealed, and raced at breakneck speed down the autobahn — famously, the world’s only major highway system with no speed limits. In short: I drove like a maniac — and the treatment began to take effect. My patient awoke from his lethargy and started screaming, whimpering, and crying. He vomited and evacuated the contents of his bowel and bladder onto my upholstery. Eventually, he slumped back in his seat, completely exhausted and unresponsive.

I repeated this procedure with Horst at least 30 times in the same way — just as his accidents had all occurred in the same way — but this time with no accidents: fasten seatbelts, drive recklessly, faeces, urine, vomit … and eventually calm. It may have been disgusting and unsavoury, but this is precisely what rendered the experience so intense that it caused an effective counterbalance to Horst’s previous experience, reducing his accidents in the hierarchy of significance in his brain. He learned that our drives left him stinking dreadfully, but, otherwise, nothing bad happened to him: nothing. Everything was okay. No matter how wild I was behind the wheel. The only drawback was that this course of therapy left my Mercedes practically worthless on the second-hand car market!

Horst was not completely cured after this, but that was not to be expected considering everything he had been through. He was, however, once again able to communicate with those around him. One problem he continued to face was his recurring dreams about his car accidents, which meant those experiences were constantly being re-inscribed on his memory. He would often jump out of bed at night and run away, only waking up when he hit his head against the bedroom door. In his dreams, he always managed to escape the danger eventually, which was a positive effect that rewarded his fear reaction and therefore reinforced it.

It was once again Freud who first realised that any psychotherapeutic approach must also delve into the realm of dreams if it is to be effective. This is not — as Freud thought — because of the supposed symbolic meaning of night-time phantasies, but simply because dreams stabilise the embedding and interlinking of (possibly unwanted) memories. Horst continued to dream of his devastating accidents and was able to escape from danger successfully in his nightmares, making it difficult for the experiences he had with me to establish themselves in his brain as an alternative pattern (driving = fear = no catastrophic consequences).

The result of this was that Horst’s phobia continued to return repeatedly, albeit often in a different manifestation. There was a time when Horst was able to drive again, but was no longer willing to fly. When this occurred, I took him along with me on my long-haul flights, for example from Germany to America and back. I always carried a syringe of Valium with me just in case, but I never needed it: although Horst was anxious and peed his pants on more than one occasion, he survived the ordeal.

We would share a room in hotels, and he would sleep with me in my bed. At night, I would handcuff him to myself, so that he was unable to run away while dreaming. Sometimes, after one of his nightmares, he would jump out of bed, dragging me along with him like a man being drawn through the prairie behind a bolted horse in an old western film. Horst had agreed to this treatment, incidentally, because he was determined to get over his phobia. He was prepared to do and to suffer anything to be cured.

This constant confrontation — with the ‘real impossibility of flight’ caused by the fact that a determined psychologist was always at his side — enabled Horst to regain the ability to travel by car, ship, train, and plane. Today, he leads a mobile life, although he sometimes still cowers in fear in the passenger seat when he is in the car with me (though that might have more to do with my driving style). He leads a contented life and is able to spend time and laugh along with other people. And he is now separated from the wife who had bullied him so badly in the past.

Another patient, traumatised by his time in a Nazi concentration camp and longing to be free of his obsessive recurring memories, learned to live with them by, once again, being handcuffed to me — once again, with the patient’s express permission — and being taken to visit a Holocaust museum, where we entered a reconstruction of the gas chambers. He relived his experiences, this time without them leading to pain and death. And this immediate emotional — not cognitive! — realisation was enough to free him from his tormenting dreams. It must be admitted, however, that the chances of successfully treating concentration camp survivors using confrontation therapy are limited. Nothing is truly comparable to the experiences of those who survived the industrialised murder machine of the Third Reich.

Even dog shit can be a cure

Confrontation therapy can also be used to help people with obsessive-compulsive disorder, since this is also based on fear. For example, compulsive handwashing originates in a panic-stricken but rationally understandable fear of infection, and an obsession with control originates in a desire to protect against unpredictable accidents and disasters. The feeling of relief engendered by such obsessive behaviour is perceived as the reward for those fears and leads to their deep embedding and stabilisation in memory. They sit so deep, in fact, that a patient cannot receive a ‘talking cure’ from psychotherapy. A cure depends much more on teaching patients directly, by means of an intense, emotional confrontation, that they are not in any serious danger and that their fears are unfounded.

To achieve this, I and other therapists treated patients with a handwashing compulsion by taking them for a walk through Hyde Park (I had found sanctuary in London after I was thrown out of the University of Vienna for my rebellious behaviour there). We went round picking up dog dirt and smearing it on our faces. Each in our own face, it should be noted, since when confrontation therapists do not ‘practise what they preach’, they lose all credibility. In cases like this, the therapist must be seen to experience disgust, and to overcome that feeling as a model for the patient to learn to do the same. Patients were then instructed not to wash for a week. In real terms, this meant seven days of awful stench and social isolation, as no one wanted to stay around such a smell for long. No one, that is, except the therapist, since, when necessary, we handcuffed ourselves to our patients for control purposes. And, of course, that meant not washing ourselves either, otherwise the therapy would not have worked.

Relapses were extremely rare and could be cured by a renewed confrontation.

Confrontation therapy demands much more of the therapist than communication from chair to chair or from chair to couch. This is probably the real reason why psychotherapists these days prefer to try to treat their patients through talk. Not to mention the fact that today such a confrontation could lead to legal problems (legal liability guidelines have changed a lot) for therapists who handcuff themselves to their patients and then urge them to smear themselves with dog faeces or to jump a red light.

Various studies show, however, that confrontation therapy is an effective treatment for anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder — more effective than psychoanalytical and psychotherapeutic talk therapy. And it has more chance of success than drugs-based therapies, which can inhibit the brain activity that is causing the problem, but cannot replace those activities with other, more desirable ones.

Confrontation therapy was developed as part of research into behavioural therapy and has been studied in many research projects. As mentioned earlier, it is based on the theory of extinction developed in learning psychology and neurobiology. Eric Kandel, who was honoured with a Nobel Prize in the year 2000, showed at the molecular level that repeated confrontation that does not result in the expected consequences leads to potassium molecules at the synapses (the connections between nerve cells) changing in such a way that the stimulation is reduced with each repetition. Pavlov, who received his Nobel Prize in 1904 and who described the optimum conditions for extinction, laid the foundations of behavioural and confrontation therapy. His laboratory dogs were clearly traumatised after nearly drowning when St Petersburg was hit by a flood. After Pavlov confronted them repeatedly with a simulation of the floodwaters breaking into the laboratory, they recovered and were able to take part in learning experiments again.

The aim of confrontation therapy is to force the brain to experience an intense and emotional ‘light-bulb moment’. The brain must experience directly that the feared effect of a certain behaviour — and the emotional experience connected with it — do not occur, after all. This allows the brain to develop space in the memory for other things that do not have to do with the trauma or the obsession in question. An arachnophobe will still retain the memory of jumping on the conference table during a meeting at work because she saw a spider crawling across the carpet — but those memories will no longer have the previous paralysing effect. They leave the brain in enough peace for it to continue working normally, without being overwhelmed by negative emotions.

Test jump from the Golden Gate Bridge

Charly was tired of life and wanted to end it all. He really wanted his suicide attempt to be successful. He didn’t want to be one of those losers who make a song and dance of killing themselves only to fail miserably because they were not really trying to die. So Charly decided not to leave anything to chance. He got himself a pistol, a bottle of sleeping pills, and a rope — and with those tools in hand, he set off for the Golden Gate Bridge. His reasoning was that at least one of those methods of killing himself must work.

When Charly reached the bridge, he first took the sleeping pills. With red wine, to increase their toxic effect. Then he put the pistol in his mouth and pulled the trigger. However, his aim was wrong, presumably due to nerves, and the bullet missed his brain, leaving him with a bullet hole in his mouth. Charly pulled the trigger again and heard nothing but an empty click — he had been sold a gun with just one bullet in it. He tossed the gun into the water in anger and tied the rope to the bridge railings. His figured that if he failed to hang himself properly, he would still plummet more than 50 metres and meet his death when he hit the water. Or failing that, as a non-swimmer, he would drown miserably in the bay. But Charly tied the noose too loosely round his neck, and his body was slung feet first into the water. The sound his body made as it hit the water alerted the harbour police, who rescued him immediately. As he was recovered from the water, his stomach rebelled, perhaps due to the cold of the water or the stress of the situation, and he vomited — instantly neutralising the lethal effect of the overdose.

Since that experience, Charly’s thoughts of suicide have never returned. On the contrary: he now works in social services, trying to convince people suffering from depression to abandon their thoughts of suicide. That is very much to his credit. But if he relies purely on the power of conversation to achieve that, he will not have much success. It would be far more effective if he put those suicidal people through the same ordeal he suffered at the Golden Gate Bridge. Those are the stimuli that really make a brain abandon any thoughts it might have of suicide.

Charly’s case is one of the favourites in the rich treasure trove of psychological anecdotes. It makes us chuckle. Some people feel a kind of respect for the unlucky suicide-attempter’s dogged determination to try everything he could to kill himself. What we see is that he went to the Golden Gate Bridge with the intention of committing suicide. The emotion centres of his brain were fixated on the idea that he was about to end it all. His pulse would have been racing, his veins throbbing in his temples, his body trembling, his thoughts revolving only around his approaching end, which would be final and forever. Yet in the end, it was not his final end that came, but rather — nothing. Thus, the desired effect never occurred. There is no better way to convince the brain that suicide is a completely unnecessary act.

Of course, there is the argument that men especially who are prevented from attempting suicide (women attempting suicide are less likely to succeed then men) will not infrequently try again, and are often then ‘successful’. However, such repeated attempts usually only occur if the first attempt was interrupted at an early stage in the chain of behaviour, with most of the steps towards an actual attempt at suicide never completed. In such cases, the person attempting suicide does not experience the entire chain of behaviour (preparation and failed implementation) as having no effect, but only the beginning of the reaction chain. If, by contrast, the action is carried out to completion (such as when the gun goes off but ‘only’ causes a non-fatal injury), the recurrence rate is considerably lower.

In a therapy situation, it is difficult to reconstruct a suicide scenario such as that experienced by Charly. It would involve taking the patient to a bridge, encouraging him to jump and then holding him back at the very last moment. For a period of time, we actually did that with our patients, with therapeutic success. When patients expressed a desire to kill themselves, they were asked to ‘walk through’ the entire chain of behaviour with a therapist, right up until just before the actual act of suicide, and then imagine that act as vividly as possible. However, there is a danger that this can become nothing more than training for the actual act if the expected negative side effects experienced by the patient are not sufficiently intensive or physically negative. This approach should only be attempted by experienced therapists.

Still, our results indicate that depression could also be treated using confrontation therapy. This could be done not only by showing patients that their suicidal, everything-is-pointless thoughts do not result in a desired effect, but also by showing them that they are not in fact as powerless and helpless as they feel.

The film Fearless (1993) shows what such a confrontation might look like. In this movie, a young woman called Carla (Rosie Perez) becomes depressed because she blames herself for not holding on to her baby tightly enough during a plane crash in which the child died. Those feelings of guilt lie like a lead weight on her soul, and no therapist has been able to help her. She then meets Max (Jeff Bridges), a fellow survivor of the same plane crash. He tries to help the Carla by taking her to buy Christmas gifts for her perished loved ones. However, that doesn’t help — because giving presents to dead people does not achieve an effect.

Max then straps his depressed friend into the backseat of his car and has her hug a toolbox as tightly as she can. He tells her to imagine she is back on the doomed plane, holding her son in her arms. Then Max crashes the car head-on into a wall. Both survive, albeit with serious injuries. Although Carla was prepared for the impact, she was still unable to hold on to the toolbox. She learns from this experience that she never had any chance of keeping hold of her baby during the plane crash. The result was that her brain immediately realised that her feelings of guilt were baseless.

The brain mechanism involved here is the same as that involved in the process of extinction as described earlier. Carla gets her life back. She leaves her husband, who is only interested in how much the insurance payout for their son’s death will be. And she also leaves Max. He may have cured her of her depression, but he is also a physical reminder of the sad times she now wants to leave behind her.

Moving forwards out of the backwards of depression

It must be said that there are many differences between films and computer-generated virtual realities on the one hand and actual reality on the other, and that depression rarely disappears as result of one single action. Those who have battled against depression for years cannot be cured in one fell swoop. Once a certain thought and behaviour pattern has become fixed in the brain, it takes a corresponding effort to dislodge it. Yet there’s no reason to view depression as an irreversible fate, which can at best only be attenuated somewhat with pharmaceuticals and electric shock treatments. There is something that can be done, but it takes some effort and is based on the specific way our brains work.

A certain area of the frontal brain, below the corpus callosum, plays an important part in depression: Brodmann area 25, where a large number of brain functions converge. These include our sleeping–waking cycle, which is in itself important in depression, as the condition is almost always accompanied by insomnia. This area of the brain is also a significant driver and director of the brain’s ‘thought pump’. When Brodmann area 25 is highly active, our attention is focused, and so it is necessary for concentration. If there is less activity in this area, on the other hand, we are easily distracted, which can be difficult if we need to concentrate, but can also be extremely relaxing.

In people with depression, Brodmann area 25 is significantly overactive. We still do not know the precise reasons for this hyperactivity, but scientists believe that it is triggered by experiences of loss. Many patients with depression have suffered a drastic experience of loss, especially during puberty, such as parental divorce, the death of a loved one, or a move to another city or even another country. They don’t necessarily reveal this in talk therapy, but it is almost always present in their personal history. We believe this experience of loss then over-activates Brodmann area 25, causing the patient’s thoughts to return again and again to the idea that there is no point to anything because everything always goes wrong anyway. Just as the patient’s parents’ marriage went wrong, or their beloved original home was suddenly replaced by a new, unwanted dwelling. Helplessness and lack of control unite!

Any therapy must therefore target this thought pump with the aim of weakening its effect or redirecting it. One way to do this is by using electric shocks to curb its activity, which has yielded impressive results in the treatment of depression in some studies. However, this approach is also associated with side effects, including lack of concentration and learning problems, because it also switches off Brodmann area 25’s function in focusing attention. This occurs because the electric shock triggers an epileptic seizure, which, like a blow to the head, disperses memory for a time. This can become a problem if the patient’s condition recurs and electroconvulsive therapy has to be administered repeatedly, potentially leading to permanent memory loss. Nevertheless, severely depressed patients usually agree to this serious intervention because their suffering is so great.

Cognitive therapy, however, has fewer side effects with a similarly high level of treatment success. Unlike conventional psychotherapeutic approaches, it does not seek to wrap patients in cottonwool, but confronts them head-on with their problem. For example, when a patient says he no longer wants to go to work because he is always being put down by his boss, a skilled therapist will immediately intervene and steer the conversation towards the many times the patient did not have a problem with his boss and perhaps even received praise from her. In such cases, mere talking can help tackle the problem. But this should optimally take place in motion. Thus not in the classic scenario, with the therapist and the patient sitting facing each other, or with the patient lying on the infamous couch, but rather with the patient moving forward as the conversation takes place. This evokes for the patient the opposite of his static, nothing-to-be-done attitude caused by his depressive state. It gives his brain the feeling of moving forward again at last after all the numbness and backward-looking (‘Why should I ever succeed at anything in the future when I’ve never succeeded at anything in the past … ?’), and everything the patient learns during this process will be stored in his memory in the context of this forwards motion. Not to mention the fact that walking and running increase the production of dopamine and other neurotransmitters, which leads to an increase in interest generally and an improvement in mood. It takes about 15–20 hours of cognitive and movement therapy for an improvement to set in.

Despite this, there are many areas of day-to-day life in which a therapeutic conversation, even in motion, is not enough to break the avoidance patterns typical of depression. For patients who believe they have no chance of finding a partner, it is of little help to reassure them that ‘there’s someone out there for everyone’. If they were encouraged by such a platitude and actually joined an online dating agency, for instance, and were then rejected by eight out of ten possible partners, they would only see this as confirmation of their original opinion that it is useless to even try to find a partner. Even though eight rejections from ten attempts is not such a bad average, as it means that two of those ten were successful. But a rational view is precisely the one that depressed people will not take, and no amount of persuasion will convince them. The solution then is to arrange contacts for such people (which can work even if the other person receives money for the arrangement).

A person who shuts herself away in a darkened apartment all day needs to go out into the sunshine. Talk is not enough.

At first sight, it might seems strange for therapists and their patients to embark on various social and sometimes risky escapades together. But how else is the brain to learn that the actions it has been avoiding do not entail the consequences it fears? That, on the contrary, these actions can achieve a desirable effect? Well-meaning conversation is usually not the way for it to learn this lesson — anyone who hopes otherwise might as well hope that lifting weights with just one arm will lead to the other arm gaining muscle mass, too.

Meanwhile, there is still no hard evidence that antidepressant drugs are any more effective than placebos. Marcia Angell, the first female editor-in-chief of the world’s most prestigious medical journal, The New England Journal of Medicine, undertook a thorough comparative study of all the scientific literature, including that published in her own journal, on the subject of antidepressants.13 She came to the devastating conclusion that most studies are so badly designed or distorted by the pharmaceutical industry that any interpretation of them is useless. The few methodologically sound research projects showed that antidepressants have scarcely more effect than placebo tablets. And although lithium compounds were found to offer effective treatment of manic-depressive disorders, their side effects are often very severe.

Although it no doubt requires great commitment from the therapist, and sometimes comes into conflict with traditional concepts of morality and even the law, confrontation therapy enables us to achieve the necessary intensity required to make use of the brain’s plasticity in the treatment of phobias and depression. No other approach offers such prospects. So, before agreeing to pay for psychotherapy, health insurers and authorities should promote real, targeted confrontation therapy, in particular for the treatment of phobias, depression, and addiction disorders.

But what is the solution if the problem is not anxiety or depression, but precisely the opposite: a total lack of fear and remorse?