8

The Trained Brain

living better with Parkinson’s and dementia

Chimpanzees are lucky. They are spared the fate suffered by more than 50 million people worldwide — and probably twice as many as that by the year 2050: dementia. Apart from a few elderly zoo animals, you will hardly find an ape that can’t remember where it stashed its oranges, or one that can no longer recognise its home, its relatives, or, eventually, its own self. Chimpanzee seniors are almost always still in full possession of their mental powers when they die, and their brains nearly always maintain the same volume as when they were in their prime and playing the mating game. They may become cantankerous, arthritic, hard of hearing, and half-blind, but their mental faculties are all present and correct. Enviable.

This begs the question of why chimpanzees don’t get dementia. Zoologically speaking, they are very similar to us and their brains also work like ours in many ways: they think long and hard when they want to solve a problem; they are skilful at using tools; and they murder, lie, and cheat if it is to their personal advantage. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, in Leipzig, have discovered that the genetic similarities between our two primate species are nowhere greater than inside our skulls: only 8 per cent of the genes in chimpanzees’ brains are distinguishable from those in our own (whereas no fewer than 32 per cent of the genes in our testes behave differently, for example). Despite this, we are prone to Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia, and those apes are not. Why is that?

A trivial answer to this question was recently discovered by American anthropologists.14 Simply: apes have a shorter life expectancy than we do — and this is sufficient to protect them from dementia.

The team of researchers led by Chet Sherwood at George Washington University used magnetic-resonance imaging to measure the brains of 87 human subjects between the ages of 22 and 88, and 99 chimpanzees between the ages of 10 and 51. They found that significant shrinkage in brain volume could be observed only in Homo sapiens, and the phenomenon was only present in subjects above the age of 50 — an age usually not even attained by the apes. The researchers interpreted this as clear proof that a stable brain structure and old age are basically incompatible. Or to put it another way: those who live on into old age — as is increasingly the case in industrialised nations — should not expect their brains to be able to perform in the same way they did when they were young. You can’t have everything.

Evidently, the brain reaches a critical point at around 50 years of age: its cells no longer work as well, and this is accompanied by a build-up of damaging metabolites. As a result, neurons begin to die en masse, and, since replacement of those dead nerves is incomplete and does not reach all parts of the organ, the brain shrinks. Chimpanzees, however, are spared that fate. ‘Their biological clock ticks faster, but the corresponding aging processes apparently do not affect their brains,’ explains Sherwood. That’s nice for the apes, and not so nice for us. But we should not despair, since there is also a good side to growing old, and our shrinking brain is usually sufficient to more or less get us through the day, and even still accomplish artistic and intellectual feats. Even when the degenerative process advances quickly, as in the disease generally known as Alzheimer’s. This is down to the brain’s mastery of the art of compensating.

Auguste Deter, the first dementia case described by Alois Alzheimer

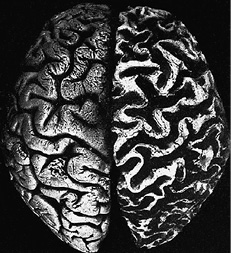

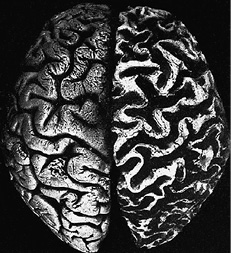

The hemisphere on the right is that of the dementia patient. The convolutions of the cerebral cortex are clearly shrunken, and the folds and fissures are clearly increased in size. As a comparison, the hemisphere on the left is from the healthy brain of a woman of the same age.

Seahorses in trouble

Emaciated and wrinkled, full of holes like a Swiss cheese — this is essentially how we usually imagine the brain of an Alzheimer’s patient to look, as if bits had been nibbled away from it. Or dried out like a sponge left out in the sun too long.

On the one hand, brain shrinkage is indeed one of the typical characteristics of dementia. On the other hand, it is a fate that none of us is spared, since several thousand of the cells of everyone’s brain die every day once we pass the age of 20. Yet the consequences of this are minor at first. For one thing, the quality of a brain’s functioning doesn’t only depend on the number of cells it contains. For another thing, the reserves are huge, with more than 20 billion neurons and 100 trillion contacts (synapses). Thirdly, the brain’s plasticity means it can compensate adequately for the loss of those cells.

However, it is well known that patients with Alzheimer’s show some pretty severe symptoms. Initially, they experience problems with their short-term memory, then their learning and speaking abilities suffer, as do their fine motor skills, and eventually they are unable to recognise familiar people and objects, and their faculties for speech and self-reflection ebb away: patients lose their ability to communicate, and their sense of self. This crescendo of decline is, however, not only caused by an accelerated rate of cell death in the brain. It is also due to fact that the decline begins in a very particular part of the brain: the hippocampus.

The hippocampus bundles together individual items of memory content to create a meaningful and understandable whole. For example, when you look at the face of your spouse, you see a forehead, two eyes, a nose, a mouth, a chin. But those sensory impressions are just the raw material, which then has to be connected to the memory content in your cerebrum to create a Gesamtkunstwerk if you are to perceive the face as that of your life partner. You first have to recognise that the moist ring of flesh encircling the teeth are ‘lips’, which means locating the concept in the memories stored in your cerebral cortex that corresponds to what you are seeing, and then you must also remember the special attributes that identify those lips as belonging to your spouse. So the hippocampus binds together the individual blossoms of our memory into a bouquet, which then causes the realisation in the cerebral cortex: ‘Ah, that’s my spouse.’

Patients with advanced Alzheimer’s disease are no longer able to bind that bouquet together. They see the eyes, ears, nose, and chin, but can no longer associate them with a familiar person. In the most severe cases, they are no longer even able to access mental concepts for what they are seeing, so they can longer recognise lips as lips and a nose as a nose. They lose the associations and contexts they once took for granted.

It is not until cell death has set in in the hippocampus that this process also begins to occur in the cerebrum. The final result is the typically atrophied brain of a dementia patient that we know from many textbooks. However, the reason why the cells of the cerebral cortex emulate the fate of their colleagues in the hippocampus has yet to be discovered.

If the flowers are not tied up in a bouquet, no one will want them. If the individual items of memory content are no longer bound together into a meaningful whole, they no longer have any meaning in themselves and they cannot be used — and anything in the body that is no longer used will atrophy, or even be deliberately destroyed to remove any ‘dead weight’. This theory seems to be supported by a recent study carried out by researchers at Berlin’s Charité hospital, in which Alzheimer’s patients were found to have an antibody against certain receptors in the brain.15 This antibody neutralises and inhibits associative information processing, which requires an intact connection between nerve cells to function.

The antibody discovery has led researchers to suspect that the condition known as Alzheimer’s is an autoimmune disease, similar to arthritis, which causes strategic confusion among the body’s immune defences, leading them to attack its own joints. This would mean immunosuppressive drugs might be effective in stemming the devastating immunological processes going on inside the skull. Or at least, they might be able to slow down the atrophying processes in the brain. However, it is equally possible that such medication has just as little effect as all the other drugs so far developed to treat Alzheimer’s disease.

The pharmaceutical industry, with its innumerable army of researchers, sees dementia as a possible source of huge profits, not only because more and more people are suffering from the condition, but also because those with the condition have it for many years, making them into potential long-term pill-takers. This is why laboratories are working flat-out, but all their results so far have been disappointing. Meanwhile, pharmaceutical companies’ profits continue to rise because their scientists and managers press tirelessly for early recognition of Alzheimer’s disease, claiming that their drugs work better if taken early (for which there is not one shred of evidence).

Anyway, the search for an anti-dementia drug has not so far resulted in successful treatment. Presumably, this is because the ultimate aim of anti-dementia medication is to halt something that simply cannot be halted: the natural ageing process. There is no treatment against getting old, and that goes for the brain as much as the body. Nevertheless, the brain can be helped to compensate for the damage caused by ageing — with pretty good chances of success.

Targeted training and stimulation

On the one hand, the fact that degeneration of the brain begins mainly in the hippocampus is devastating, because it hits right at the centre of our memory. On the other hand, this is also a region that forms the basis of the brain’s plasticity, which primarily depends on the fact that individual items of memory content can be linked in a huge variety of different ways. The hippocampus is the mastermind behind that linking process — at least for spatial associations (‘Where am I?’) and explicitly conscious episodic memories (‘My mother’s name is …’). It goes without saying that the hippocampus needs to be extremely plastic in order to perform this function, which in turn means that even in the case of progressive degeneration, it retains many possibilities for maintaining its functionality.

But this is only the case if those resources are in regular use, and so the hippocampus requires training and stimulation. Most people are now aware of the fact that the progress of dementia can be slowed down effectively by remaining active for as long as possible. Buzzwords like ‘brain jogging’ and ‘mental performance training’ imply that the brain can be kept fit by constant use, just like any other organ of the body. However, the aspect that is often overlooked is the importance of how the brain is used. Busily solving crossword puzzles is of little help because, although that activity does involve extracting individual items of memory content from their mental drawers, it does little to help establish connections with other memory content, and thus with the hippocampus. Far better training effects are achieved through contextual learning, for example by integrating terms to be memorised into a story. And the training effects can be further heightened by creating a story that is patently absurd. So, to memorise the words ‘plane’ and ‘giraffe’, it is a good idea to visualise a giraffe sitting on a plane. This is an unusual association — and it’s the kind of thing that trains the brain far more than solving crossword puzzles.

Indeed, anyone looking to train their brain should make a point of seeking out the unusual, in the sense of things they are not used to. When a computer specialist spends every day analysing bits and bytes to the point of exhaustion, or a chess grandmaster repeatedly plays out historic games in her mind, it will not do much to stave off dementia. It’s like a veteran footballer who keeps on playing despite the twinges of pain in his knee — setting a course towards overstraining the ligament and making the condition worse, until eventually his knee is ruined. A better course of action would be to try out other forms of exercise, such as swimming or cycling, allowing him to go easy on his damaged meniscus while building up muscle and other tissue structures that will take the strain off his problematic knee. Not to mention the fact that it would also help keep him active and healthy. And this strategy of making activity as varied and flexible as possible, rather than repeating the same patterns over and over again, is also the one that achieves the best results for the brain in the battle against degeneration.

A study carried out at Boston University shows how this can be put into practice.16 Thirteen Alzheimer’s patients and 14 healthy older adults were asked to learn 40 children’s songs that were previously unfamiliar to them. They were allowed to read the lyrics several times while receiving different kinds of support input: 20 of the song lyrics were accompanied by a corresponding sung recording, and 20 were accompanied by a spoken recording. Thus the visual stimulus of reading the text was associated with musical or spoken language stimuli. It may be assumed that some of the subjects would have had experience of the latter combination of stimuli, for example during a language learning course, but the subjects were unlikely to have experienced the first combination.

For the healthy participants, there appeared to be no performance difference in learning songs supported by spoken or sung recordings of the lyrics. The important thing for their brains was that they were able to associate the lyrics with some kind of stimulus, whether spoken or sung. By contrast, learning was much easier for the dementia patients when it was supported by musical stimuli. On the one hand, this corroborates clinical experience, which shows that the ‘musical parts of the brain’ are destroyed very late in the degenerative process caused by Alzheimer’s disease; they survive intact for a relatively long time. On the other hand, it also shows that confronting dementia patients with brainteasers and learning tasks that force them to form new associations can be effective. Clearly, this stimulates the plastic reorganisation processes in the brain.

Simply listening to music, however, offers about as much protection against dementia as watching television every day — that is, basically none. This is because it is a process that involves only consumption, and thus does not promote any kind of active learning or associative effort. Music must be combined with some kind of activity that demands associative effort of the brain. This may include not only learning song lyrics, but also performing motor tasks such as dancing or active music-making.

On average, active musicians develop Alzheimer’s relatively late in life, and few conductors, whose profession means they are constantly moving to music, develop the condition at all. A number of studies have shown that a combination of active music-making and cognitive training (including brainteasers, memory games, and word puzzles) forms an effective strategy in the battle against various kinds of degenerative brain disease. Given the right instruction, patients can train independently and alone, but working in small groups has proven particularly effective. In either case, the exercises should be repeated as often as possible. This method can enable Alzheimer’s patients to remain active in normal everyday life for around two years longer, which is a significant improvement considering that they can expect to live only another seven to ten years after their diagnosis. It is an improvement which benefits not only the patients themselves, but also their families and their care insurers.

However, it is of course also possible to achieve such an improvement without music, and even without tricky mental puzzles, as long as the brain is sufficiently stimulated. A team of researchers at the University Medical Centre Hamburg-Eppendorf motivated subjects between the ages of 50 and 67 to complete a three-month training course in how to juggle. The subjects’ brains were measured before and after the training program. After the training phase, the scientists found an increase in the size of the area of the brain that specialises in motion and spatial awareness. They also discovered an increase in the size of the hippocampus. This was undoubtedly due not only to the fact that juggling places many different demands on the brain, from motor skills to coordination and spatial orientation, but also to the fact that their brains were engaging in a new activity, requiring them to create new neural pathways, which were completely or almost completely lacking before.

Music-making and the brain

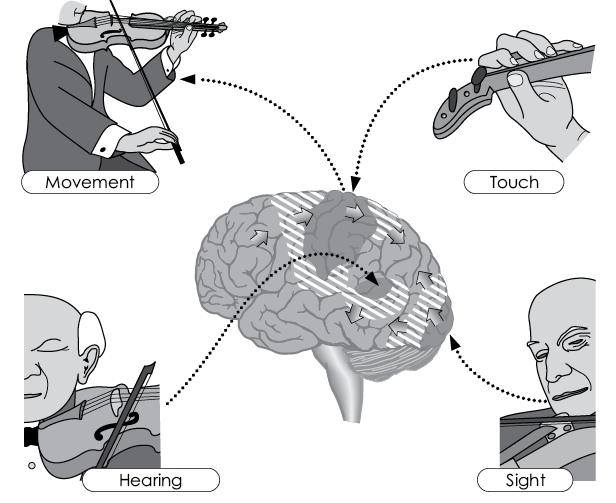

Growth and increased connections in the brain (positive neuroplasticity) are especially promoted by active music-making because it causes complex acoustic (hearing), motor (playing, singing), visual (reading music, watching fellow musicians), and tactile (feeling the instrument) excitation patterns to converge simultaneously and in immediate succession in the temporal lobes and the shaded central areas of the brain, where they are connected with each other associatively.

Not included in the illustration but of equal importance are the simultaneous emotional activation and the logical connections created by reading or reproducing musical notation, as well as all types of memorisation and learning (conscious and unconscious) in the temporal lobes, hippocampus (conscious), and the basal ganglia (unconscious).

Tuning the brain to the right wavelength

In Tübingen, we have carried out some successful work using a combination of cognitive training programs and electrical stimulation. This involves attaching contacts to patients’ heads to pass certain electrical impulses through their brains. These impulses are not strong enough for the dementia patients to feel them, and thus they are not comparable with electric-shock treatments. However, they are strong enough to have a positive influence on learning.

To understand why, it is necessary to know that neurons communicate with each other in networks by building up an electric charge until they ‘fire’. In an ideal learning process, many nerve cells will fire simultaneously, and if that happens often enough, the connections between those cells will become fixed — and the learned material is embedded in the memory. However, this is precisely the mechanism that breaks down in dementia patients: their neurons are no longer able to build up sufficient charge, and their firing is weak or non-existent. But it is possible to restart that process by providing the desired electrical charge from outside. This type of external stimulation is like giving a ‘jump-start’ to actions of the brain that it was designed to perform anyway: namely, building up electrical charges and transferring them between neurons.

This doesn’t mean that such a jump-start is like an alarm signal, as if to say, ‘a little electric shock to the head will increase alertness’. The effect of this electrical stimulation is rather the direct opposite. It often even produces the kind of brainwaves typical of deep sleep, as that phase of sleep is normally characterised by particularly intensive neural firing in order to fix permanently in the memory that which has been learned during waking. In small children, this phase can take up more than a quarter of a night’s sleep, while for older people it is only very short, and patients with advanced dementia barely experience such a phase at all. But if the brains of patients with early-stage dementia are fed the necessary brainwaves by means of electrical stimulation, giving them back their deep sleep in a way, their memories can be given a jump-start — as long as they continue to train their brain as well. Electrostimulation cannot replace practice; it can only be a complement to it and help stabilise its successes. If nothing enters the brain for it to remember, it cannot practise memorising.

Training, learning, and electrical stimulation can all take place simultaneously if the stimulation takes place while the patient is awake. In the 1980s, when we first measured the slow brain potentials of our patients and research subjects while they completed various mental tasks, we noticed that performance was always improved whenever those potentials indicated a state of readiness in the brain. That realisation gave us the idea of trying to produce such a state deliberately, using weak electrical stimulation from two electrodes placed over areas of the brain responsible for certain functions. This was the birth of transcranial direct-current stimulation (tDCS), which is so popular today.

We carried out a large number of experiments using ourselves as guinea pigs, and some of them yielded results that were nothing less than philosophical in their dimension. For example, we administered the current to the left hemisphere, or the right, without the test subjects’ knowledge. When they subsequently completed motor tests, they always used the hand on the opposite side to the side of their brain that had been stimulated, while their other hand remained virtually unused and the test subject showed no inclination to work with it. We had manipulated the subjects’ will, which raises the question of how much ‘free will’ human beings can really be said to possess.

Parkinson brains and champion compensators

Like dementia, Parkinson’s disease does not strike patients out of the blue. Rather, it is a gradual process, which the brain can counteract to a certain extent. This may be seen by simply observing the progress of the disease. It is caused by the death of dopaminergic cells in the substantia nigra (a central area of the midbrain), causing ever lower levels of dopamine. This neurotransmitter is extremely important, because it is dopamine that makes us into creatures with drive and motivation. It is also necessary for motor control. This might lead us to expect that a lack of dopamine would quickly result in those infamous symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, such as slowness of movement, rigidity, and shaking. Yet this is not the case.

Rather, although cell death in the substantia nigra often begins very early, sometimes as early as 35 years of age, without the patient noticing anything, symptoms don’t usually appear until between the ages of 50 and 60, when 60 per cent, or sometimes even 80 per cent, of the dopaminergic cells have died. The brain manages to cushion the increasing lack of dopamine for many years, although the substance is as important as oil is for your car’s engine. This is a masterly piece of compensation — and if we could find a way to increase it, we would be able to slow the disease’s progress even further than we now can.

Drugs used to treat Parkinson’s, such a L-DOPA, have the opposite effect, because they shut down this compensatory process by providing the body artificially with dopamine and removing the need to compensate. This can even lead to the body eventually ceasing any residual dopamine production of its own, leaving it unable to contribute anything to the metabolism of this neurotransmitter. This throws the balance of transmitters in the brain out of kilter, and patients lose their last modicum of motivation and can often only sit in a wheelchair or lie in bed, apparently indifferent to their environment.

Of course, this kind of treatment can still be appropriate for older patients, as it offers them certain relief from other symptoms during the short time left to them. For younger patients, however, the approach must be a different one, since they can expect to live for many years with the disease — and so their treatment should make use of all the resources offered by their own bodies.

When Parkinson’s patients jump up from their wheelchairs

There are probably several aspects underlying the compensatory achievements of a brain damaged by Parkinson’s disease. It is known that dopamine is produced not only in the substantia nigra, but also in other parts of the central nervous system. There is some evidence that those dopamine production areas kick in when the core dopaminergic region stops working. Another way of compensating involves restoring the balance of transmitters by reducing the production of dopamine antagonists such as acetylcholine. Furthermore, a team of German researchers has discovered that even before the appearance of their first symptoms, patients with Parkinson’s disease activate significantly more of the motor areas of the brain to execute a given movement than do others. It is almost as if the brain decides to spread the burden of the task when it is weakened by a dopamine deficiency.

These are all plausible hypotheses, but ultimately, the mechanisms for these compensation strategies remain unclear. The important thing is that they work — and they work particularly well in the case of Parkinson’s disease, although their effect is greater during the initial phase of the disease than in its more advanced stages.

This explains reports of Parkinson’s patients suddenly leaping out of their wheelchairs and running away when immediate danger threatens, for example from a fire. Others show no emotion on their mask-like faces until their birthday party comes around, when suddenly they are all smiles, as if their illness had left them completely. For a long time, such incidents caused people to suspect that patients with Parkinson’s might simply be faking it. What they actually are is proof of the brain’s ability to compensate for losses — and proof of the fact that certain situations in particular encourage the development of those powers.

A jump-start for the joker in reserve

Of course, we can’t scare Parkinson’s patients to death every time we want to get them on their feet, and it is not practical to celebrate their birthday every day in order to bring a smile to their faces. However, there are other situations and changes to their environment that can be used to encourage them to make use of the compensatory resources of their brains.

A line of tape stuck to the floor, leading from the patient’s favourite spot to the toilet can often enable them to go to the loo alone, even after they are otherwise no longer able to do so. And, of course, a similar trick can be used to point the way to other destinations, such as the patient’s bedroom or front door. The tape has the added advantage of stimulating patients to head off for these destinations independently.

Another example: patients with Parkinson’s are often very wary of climbing stairs without a handrail, leading them to avoid stairs or to be reliant on help to negotiate them. But as soon as they see a handrail, they approach the staircase without trepidation. When their movements get stuck mid-flow, concentrating on the ascending line leading to the top of the staircase can help them get moving up the stairs again.

But why do strips of tape and staircase banisters get people with Parkinson’s moving again? Is it that they give the patient a sense of security? This would somewhat contradict our example of patients running away from fire, in which the exact opposite — acute danger — causes them to move. An immediate hazard appears to mobilise huge powers for a moment of shock (secreting dopamine from their remaining cells), which however does not mean that patients can call on those powers at will in everyday life when they are not in shock. This leads us to assume that their reactions are based on something else entirely, which once again brings us back to the brain’s constant desire to achieve an effect. The tape and the handrail — both bring patients closer to their goal by guiding them in the right direction. This indicates to the brain that the planned action will actually end in success, making it easier for the brain to make a connection between the journey and the destination, allowing it to access its reserves of dopamine to make the action possible.

Thus, tape on the floor does not get patients with Parkinson’s disease moving because it indicates where the toilet is. Patients usually know that already. And despite the propensity of neurologists and psychiatrists to resort to the term ‘Parkinson’s dementia’, patients do not necessarily always suffer from cognitive limitations. Rather, their problems lie in an inability to communicate with their environment at a normal speed, if at all. Tape on the floor gets them moving because it conveys the meaningfulness (the eventual effect) of that action and thereby causes the brain to activate its compensatory powers.

You could say that tape provides a jump-start for the brain to play its reserve joker. Just as a motorist whose car is running on the last drop of fuel is finally convinced to use the canister of petrol in his boot rather than saving it in the belief that it might be useful when times get tougher.

Solidarity inside the brain

MRI neurofeedback can also help in these cases. Naturally, with Parkinson’s patients, attention is focused on the areas of the brain that are important in motor function — not just those areas that are weakened, but also those that are able to compensate for the lost functions of the weakened areas. When patients manage to increase the flow of blood to those areas of their brain, they see this represented on a computer screen.

It is important that patients are given no instruction about how they are to increase the blood flow to those parts of their brain. They are free to choose what to think or feel in order to achieve this. It may be thinking of a dear friend, or imagining walking through a forest, sailing round the world, or watching a football final — it’s entirely up to the patients themselves. Clinical experience has shown that those patients who are not really able to explain what was going through their mind when the anticipated symbol appeared on the screen are the best at directing blood to the desired areas of the brain. This is presumably because those areas are located deeper in the brain, beyond the reach of reflection and conscious memory.

A Dutch-British team of researchers achieved impressive results with MRI neurofeedback treatment for patients with Parkinson’s disease.17 The patients’ motor function increased by 37 per cent after just two sessions, based on the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, the international tool for measuring the stage of the disease. However, it remains to be seen whether this result can be transferred from the lab to everyday life. Nonetheless, the results are encouraging because they were achieved in only two sessions, which appears to indicate that the plastic powers of the brain can be activated relatively quickly. Furthermore, during this study, the blood supply increased not only to the target areas of the brain, but also to other regions that play a key role in initiating and controlling movement, including the subthalamus and the globus pallidus, which, in evolutionary terms, is part of the midbrain.

This once again shows that the individual areas of the brain can never be considered in isolation. When one weakens, others come to its assistance; and training one region necessarily means training others along with it. There are no lone wolves inside our skull, just team players all pulling together — unless they are being manipulated from outside. Unfortunately, this is precisely the strategy pursued by a psychiatric and neurological system dominated by the pharmaceutical industry.

Instead of pursuing that path, more funding must be approved and programs must be introduced to investigate scientifically the possibilities offered by neurofeedback for the containment of Parkinson’s disease and dementia. Lobbying by pharmaceutical companies cannot be a basis for this, since, understandably, they have no interest in brain-training methods. So the patients themselves, as well as their families and advocates, must demand that such funding be provided. This has been far too rare an occurrence in the past. Patients and their families are rarely given information about neurofeedback because doctors generally do not believe that a physical disease can be controlled in this way.