11

Nirvana

is there life beyond greed, addiction, and want, want, want?

Bunga bunga! It’s a phrase that did the rounds in the media a couple of years ago and has now passed into general usage. No one is really sure where it came from or what it originally meant. It seems to have first appeared around the turn of the last century, in the context of British colonialism, perhaps as a reference to the immoral goings-on in the harems of African and Middle Eastern rulers. It is clearly meant to sound as if it comes from a ‘primitive’ language of the jungle or the bush. This was a way of reinforcing differentness: wild savages with their unbridled sexuality, contrasted with the decent, upstanding colonial overlords, whose moral superiority gave them the absolute right to rule over such barbarians. But few people these days are aware of this historical background when they hear the phrase ‘bunga bunga’.

Today, ‘bunga bunga’ conjures up images in our minds of old men cavorting with much younger women. Men like the octogenarian Silvio Berlusconi, who did not stop appearing in public with his young female playmates even after a court sentenced him to seven years in prison for paying for sex with an underage girl. Or like the nonagenarian Hugh Hefner, who still likes to surround himself with Playboy bunnies and who, on New Year’s Eve 2012, married a woman young enough to be his granddaughter.

In this way, ‘bunga bunga’ describes an inability to stop doing something even when it’s no longer in a person’s best interests, or, worse, when it is associated with disadvantage. Like a smoker who can’t kick the tobacco habit, these men are unable keep their hands off young women, even in extreme old age, and even if their behaviour makes them look ridiculous in most people’s eyes.

I do not intend to stoke any kind of moral outrage by mentioning this, since no one has the right to stick a sell-by date on older men’s sexual activity, or to demand that, if they really must have sex, they’d better do it with women of their own age. But even a free spirit like the American pop artist Andy Warhol once claimed that true freedom only comes once you’re through with sex. So it seems legitimate to ask why the Berlusconis and Hefners of this world don’t finally go into sexual retirement and enjoy the wisdom and liberty of old age. And, more generally, why so many people find it impossible to stop pursuing their desires and addictions although they know from experience that they will not provide ultimate satisfaction, but rather a short-term kick until the next urge comes along.

This behaviour pattern is not confined to old men continually chasing after young women and girls. When financial speculators unhinge the entire global economy with their rampant risky dealing, it is once again a case of ‘not being able to get enough’, which can refer equally to the actual money and the adrenaline rush they are chasing. The unbridled desire for power displayed by dictators and absolute rulers, which costs the lives of millions of people every year, also fits into this category, of course, as do the countless numbers of people who are trapped in addiction.

Strongly physically addictive drugs like heroin play only a minor role here, as psychological addictions are far more widespread. Innumerable people are hooked on gambling, interactive computer gaming, and the internet. Others’ eating habits are out of control and they are unable to stop themselves, even when their obesity leads to health problems and social isolation. Others become stalkers, violating the privacy of the object of their obsession.

There appear to be no limits on the variety of addiction — we now even have many cases of ‘tanorexia’, the obsessive need to lie in the sun or on a sunbed until the skin is more reminiscent of tanned leather than human tissue. Other addictions even seem to have become generally acceptable: when the actresses in ads for online shoe retailers shriek ecstatically over their newly delivered shoes, the implication is that shopping addictions have become socially acceptable. At least here in Europe.

Lists of possible addictions go into the dozens or even hundreds, depending on who draws them up. The German Professional Association for Addiction puts the number of people in Germany who are addicted to drugs and alcohol at 3.2 million; 3.8 million are thought to be addicted to nicotine; and then there are the non-substance-based addictions, to shopping or gambling, for instance. The German government’s drugs commissioner speaks of 16 million smokers, 1.3 million alcoholics, 600,000 regular cannabis users, and more than 500,000 gambling addicts, as well as an estimated 8 per cent of users who are addicted to the internet. However, none of those figures are particularly reliable. This is firstly because experts still argue over what exactly should be labelled an addiction. Secondly, very few people are addicted to only one thing, so there is much overlap. Thirdly, the statistics gathered about psychiatric and psychological disorders in general are rather vague. ‘In Germany, pigs are counted three times a year, and the fruit harvest is enumerated several times annually,’ laments the Düsseldorf-based sociologist Karl-Heinz Reuband, ‘but the number of people admitted every year to hospitals or psychiatric institutions with particular diagnoses is not recorded in any statistics.’

Nonetheless, we can be certain that addiction is a mass phenomenon. Addiction are such a mass phenomenon that it begs the question of whether many of them can still be called pathological, or whether they have become a part of ‘just the usual craziness’. When we take a closer look at our brains, it seems we must conclude that this is most likely the case.

The liking hardly changes — but the wanting increases

Arthur Schopenhauer believed the will to be ‘the eternal and indestructible in man’. Although he believed there were differences in the concerns of younger and older people (‘The character of the first half of life is an unsatisfied longing for happiness; that of the second is dread of misfortune’), and he recognised the possibility of affirming or denying the will, he believed that, in itself, the will was both infinite and everlasting: ‘All philosophers have made the mistake of placing that which is metaphysical, indestructible, and eternal in the intellect. It lies exclusively in the will.’

Schopenhauer’s great philosophical insight also holds true from the point of view of brain research. The will — in the sense of desirous wanting or wishing — is the anticipation, the expectation of the effects that result from our behaviour, and so it is indeed indestructible, and it also forms the basis of almost every learning process. However, in recent decades a distinction has established itself that offers a better explanation for why ageing playboys continue to seek the company of younger women in their old age, or why elder statesmen insisting on chain-smoking despite their doctors’ orders. We now distinguish between liking and wanting — and while the things we like change only negligibly, our will to get them increases continually.

An example from ordinary life might help explain this distinction better. There are many different things we might like. These can include sunsets, going to the cinema, beautiful faces, or sausages with sauerkraut. But we don’t feel the need to do everything in our power to have or experience these things as often as possible. We have no difficulty doing without them for a couple of days or even weeks.

However, in principle at least, any of these things can potentially become the object of a stronger desire, which could eventually become so powerful that we feel we can no longer do without them. Sunsets and sausages with sauerkraut can become an addiction just as much as cigarettes and alcohol. Due to the psychotropic substances they contain, which — unlike sunsets — directly affect the systems in the brain that control wanting, cigarettes and alcohol do pose a greater risk; but in principle we can develop an irresistible desire that even goes as far as a dependency to anything we like.

Anyone can become addicted to almost anything

Let’s assume you’re a fan of beautiful sunsets. You share this love with other people, and nobody thinks anything of it when you pull your car over of an evening to admire the picturesque scene from the roadside parking area, as the red orb in the sky slowly descends below the horizon. For most people, this would be enough to satisfy their desire to experience the spectacular wonders of nature for quite some time. But for you, watching the sunset at the side of the road is more than just a pleasant interlude; it triggers intense feelings of euphoria.

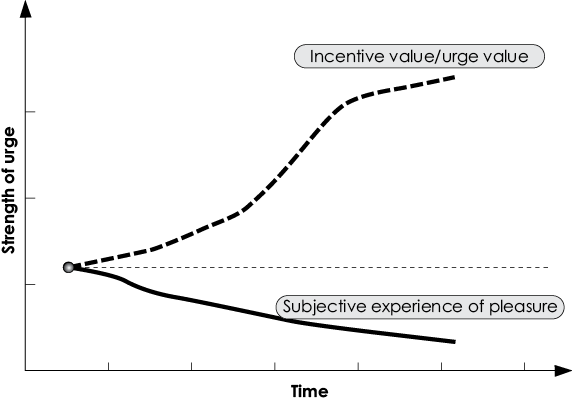

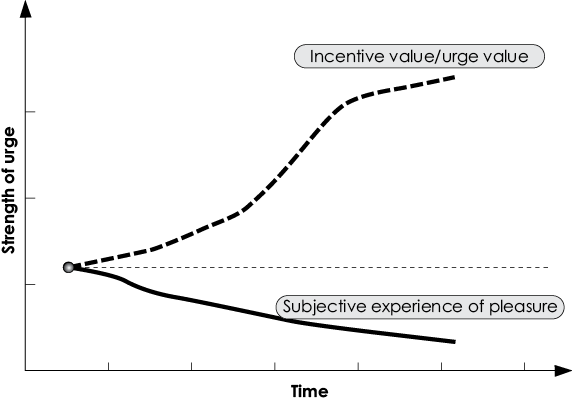

The development of ‘wanting’ and ‘liking’

This graph shows the development of ‘wanting’ (wishing for, top curve) and ‘liking’ (bottom curve) over time after repeated positive stimuli (e.g. from consuming drugs) or behaviour leading to positive feelings of satisfaction (e.g. having sex).

The attractiveness (or the ‘incentive value’) of positive stimuli increases exponentially with each repeated experience, while the subjective experience of satisfaction slowly declines: the latter phenomenon is often described as habituation. The rapid increase in the desire to experience a given stimulus is associated with the increased release of the neurotransmitter dopamine in the brain.

And so, the next evening, you drive to another roadside layby to repeat the experience one more time. It works, and once again you experience pleasure and sensual satisfaction. And so it goes on, until, eventually, laybys are no longer just laybys, but hold the promise of intense feelings of delight and euphoria. You now feel a thrill of exhilaration whenever you approach one, just like the thrill a shopaholic feels when she enters a boutique, or a porn addict feels when he switches on his computer. The actual event, the sunset, no longer takes centre stage, and is replaced by the layby that holds the promise of a beautiful sunset.

Boutiques, computers, and roadside laybys are nothing special in our modern world. Often, we don’t even notice them, and, even if we do, they have little significance for us. We make use of them whenever we need to, but, beyond their pragmatic purpose, we are indifferent to them. However, if our brain connects them with a powerfully pleasurable stimulus, they increase dramatically in significance for us. This is what psychologists call salience: the stimulus is taken out of context, losing its neutrality and taking on enormous meaning. It’s like a spot of red colour that jumps out at us from a sea of blue. The layby is no longer just a random place by the roadside, the boutique is no longer just a dress shop, and the PC is no longer just a work tool; they now harbour the promise of euphoria — and it is to that promise that we are liable to become addicted.

Such an addiction adversely affects people’s behaviour in social and work situations by causing such an obsession that their perception is dominated by it. They spend the whole day waiting for the evening; they can think of nothing else, and refuse all invitations that do not include a sure promise of a sunset — until their whole lives revolve around sunsets. If no sunset happens to be available at a given moment, they enthuse with other sunset addicts online or engage in replacement activities, such as collecting photos or paintings of sunsets. If they can’t get their regular fix, due to days of extended cloud coverage, they become increasingly nervous and restless and unable to concentrate. Eventually, they might start to film sunsets in order to guarantee a constant supply and to enable them to enjoy the spectacle even during the hours of daylight. Old friends and acquaintances find this obsession difficult to understand and begin to turn their backs on the sunset addict in irritation.

Of course, the addicts themselves become increasingly numbed to the effects of sunsets as time goes on, and the scenes have to be ever-more intense and impressive, which prompts the addict to head off to ever-more remote corners of the Earth. And the pinnacle is an evening flight heading west, which offers a permanent sunset to admire. All that travelling eventually leads to financial ruin, social isolation (except from fellow addicts), and unemployment, after getting caught by the boss ogling sunsets on the computer at work …

Of course, the chances of becoming addicted to sunsets is relatively small, not least because we get to see them too rarely. By contrast, the danger of becoming dependent on online chat, video games, or pornography is much greater because such addictions satisfy vital and fundamental human needs, such as the need for communication, adventure, excitement, or sex. Theoretically, however, almost any positive, and even some negative experiences and stimuli can become the object of an addiction — in the case of anorexia, this can even be the person’s own body, or rather the negation of it — because these things anyway become less and less significant as the addiction develops. After a few fixes, even heroin can no longer provide the initial euphoric effect on its own, but still the addict’s body and brain crave it. At that point, the anticipation of the pleasurable experience, the expectation of the moment of fulfilment, has become more significant than the act of satisfaction itself — and this is precisely the vehicle on which it is possible to slide into addiction to practically anything.

Thus, addictions do not come about, as believed by many people — including many doctors, psychologists, and addiction therapists — as a result of the negative stimulus of withdrawal (for example: as a result of the shakes and nausea we experience after a night of heavy drinking, as the alcohol level in our blood sinks, leading us to reach for the bottle to alleviate those symptoms). Such a mechanism does play a supporting role, but of far greater importance is the fact that the incentive value of the situations associated with the object of addiction increases, even when the object itself is no longer so attractive.

This is the reason why 80 per cent of addicts relapse within a year of withdrawal. An alcoholic may emerge clean from the clinic, but the next time he walks past a bar, he will still be drawn as powerfully to enter it as he was before, which is why the danger is so great that he will dismiss all good intentions and go in and get drunk. A smoker may be determined to cut cigarettes out of her life on the stroke of midnight on New Year’s Eve, but as soon as she finds herself in day-to-day situations in which she would routinely light up, such as with that first cup of coffee and the newspaper in the morning, or in front of the TV with a glass of wine in the evening, she will suddenly find herself facing a huge problem: her brain telling her in no uncertain terms that the pleasure of that morning coffee or that evening glass of wine is only complete with a cigarette. These are the situations in which people relapse — and no one, even with the best will in the world, is immune to them: from a homeless heroin addict to a rich and successful football manager such as Germany’s Uli Hoeness, who, during his tax-evasion trial, admitted to rampant, unbridled gambling on the financial markets. He ignored the risk of losing his entire fortune and, as a person in the public eye, the danger of becoming a national laughing stock in exactly the same way as heroin addicts ignore the physical decline of their bodies. The power of positive association is too great to allow such fears to gain the upper hand.

In the case of Uli Hoeness, the accusation was often made that a man of his experience should never have reached the point where he was permanently glued like a teenager to his smartphone or laptop, speculating on the financial markets. But there is no reason to hope that such urges, and thus the risk of addiction that goes along with them, will become less pronounced as we get older. On the contrary, although satisfying such wants happens less, the wanting itself actually increases. This explains why there are so many men whose impotence means they can no longer have sex at all, but who still gawk at any woman in a short skirt. There are enough examples from history to prove that lust for power increases continually over the course of the years and takes on ever more brutal forms, and this doesn’t apply only to dictators such as Hitler or Stalin.

Also, the idea that addictions appear mainly in younger people is wrong. In Germany, 1.5 million people over the age of 60 are addicted to sleeping pills and tranquilisers, and this is not an addiction they have had since their younger years, as is often the case with smoking, but rather one they have developed in old age. It happens according to the pattern described above: in the beginning, there is the wonderful experience of finally being able to get a good night’s sleep, with the aid of benzodiazepines; later, the brain can no longer imagine sleeping without them, although the body’s physical habituation processes mean they no longer have very much pharmaceutical effect.

Better dead than without dopamine

The great importance of joyous anticipation and association in the development of addiction can also be described in neurobiological terms, in particular in terms of a certain functional system: the mesolimbic dopamine pathway. It is made up of cells with long axons originating on the border between the midbrain and the interbrain and stretching all the way to the frontal regions. When this pathway is stimulated, it can trigger an urge to act that overrides any feelings of caution, even to the point of self-destruction.

In one experiment, hungry rats were placed in a T-shaped labyrinth. Food was available in the branches of the T, and in the longer section there was a lever that they had been taught would electrically stimulate their dopamine system when they activated it. It should not be forgotten that these animals were hungry, and the path to available food was short and easy.

However, once the rats had understood which reward was to be found where, they went exclusively for the electric stimulation. They pressed the lever up to 5,000 times a day, until they were too exhausted to press it any more. It was as if they would rather die than live without their dopamine fix. They even abandoned their young and their sexual partners, and were prepared to jump electrified dividers to get their fix. They also continued to do so even when researchers denied them the reward of the electric impulse for a time: the mere anticipation and association of the reward stimulus with the corresponding branch of the T-maze was enough to make them try to get there.

Observations of the dopamine systems of people who are addicted to nicotine show that these are considerably more active before they get their fix of the drug than during intake. And their dopamine system becomes especially active if the drug is not administered at the expected time. What this means is that dopamine levels are among their highest before the final object of wanting is attained, and reach an even higher level after the want fails to be satisfied, but there is no surge in dopamine release while the drug is being consumed. This explains why a smoker who is still smoking a cigarette will fidget like a nervous squirrel if he realises the packet is empty. It has absolutely nothing to do with withdrawal — after all, our smoker still has a lit cigarette between his lips. Rather, this reaction comes because the smoker’s neurobiology is now absolutely tuned to wanting.

What pubs and churches have in common

Against this background, we must consider whether addiction should really be seen as a medical issue at all, since recognised dependencies such as alcoholism or gambling addiction are controlled by the same circuits in the brain as romantic love and strict religious belief. These control circuits mainly function like this: there is something that we like (it is not possible without this — no one can become an alcoholic if they don’t like alcoholic drinks or the effect they have!), and there are situations that increase the feeling of wanting it. For alcoholics, this may be the hubbub of a crowded bar or the fun atmosphere at a party; for the pious believer, it might be the sight of a church or actual contact with a sin. Ultimately, however, the two behaviour patterns boil down to the same thing: a learned motivation in anticipation of something that is experienced as pleasurable.

The fact that dependencies on drugs like heroin, nicotine, and alcohol can cause sickness and death is in no doubt. What is doubtful, however, is whether an irresistible desire for something should be generally branded as pathological. By that logic, married couples who have nothing more to say to each other after 40 years together but do not break up, because neither one can imagine life without the other, should be labelled as sick. Eating breakfast or watching TV alone is unthinkable for them. Just as the smoker’s brain cannot bear to do without that postprandial or post-coital cigarette. Some widowed partners actually suffer from extreme withdrawal symptoms, and many soon follow their spouses to the grave. Their behaviour is described as unbreakable loyalty, while smokers are branded addicts and forced into glass cages at airports, the likes of which are usually only seen imprisoning the defendants at show trials in totalitarian countries. This does not seem very consistent. For this reason, the World Health Organisation (WHO) speaks of a dependence requiring treatment only if it significantly impairs the person’s daily life and leads to health problems. But it also expressly states that these circumstances can also be caused by such things as love, jealousy, and monetary greed. This insight has not yet made its way into the canon of psychiatric practice or addiction therapy.

We must accept the fact that every brain has an enormous potential for addiction. This is the dark side of the phenomena we have been examining so closely: the brain’s constant quest for effects (especially its pursuit of rewards) on the one hand, and its great plasticity on the other. The quest for effects (anticipation of rewards) sparks interest in the brain and triggers action; the brain’s plasticity means it can focus on almost anything as the object of that quest. This object may be dangerous or even threatening to the brain owner’s very existence — as shown by the experiment with the rats who preferred to get a dopamine fix than to fill their empty stomachs. But brains don’t necessarily think about the repercussions of their actions or the best interests of their owners — what they care about is achieving the effects they crave, the immediate satisfaction of a need or desire.

Escaping addiction

A harmful addiction must, of course, be treated if the person in question is unable to learn self-control. A behaviour-therapy-based option is offered by aversion therapy, based on the principle of conditioning. Consumption of the addictive substance is deliberately associated with extremely negative stimuli. This might be a harmless but painful electric shock; for those trying to quit smoking, it might also be a deliberate overdose caused by smoking a large number of cigarettes in quick succession to the point of nausea — with the process being repeated several times a day. This ‘rapid smoking’ is, however, only effective if it takes place not only in a scientifically controlled environment such as a psychotherapist’s practice, but also in the natural environment in which the nicotine addict would normally smoke. As I already described, addiction therapies must focus on the situation in which the object of the addiction is consumed.

This is why sending teenage drug addicts to the countryside for treatment is unlikely to lead to long-term success. They may indeed stay clean for a while during their stay on a farm, but as soon as they leave that neutral location and return to their usual environment and social circles, every street, bar, park, club, or public toilet will remind them of their past life. Their old friends and acquaintances are still using drugs as they did before, increasing both availability and peer pressure to particularly high levels, and so the young addict in treatment is advised to stay well away from them. But this will probably lead to isolation and confrontation with the fact that they have become part of the ‘boring mainstream’, which they always professed to hate. Constant sobriety does not necessarily make the world a more interesting place; on the contrary, it is hard work resisting the urge to get high. Especially if you know that all you need to do is go round the corner to the nearest club and snort a bit of coke to escape the misery. Very powerful positive incentives for self-control are necessary to prevent a relapse in such a situation. So much so that it seems almost miraculous that some people manage to remain abstinent.

Withdrawal is only the first step. Smokers also face the question of how to deal with situations in which they would normally light up a cigarette. What are they supposed to do while they are at their desk, waiting for the computer to boot? Or when they’re stuck in traffic, or waiting for the bus? How can they escape the peer pressure of their still-smoking friends without putting their friendships in jeopardy?

This is why addiction therapy has the greatest chance of success if all the ‘dangerous’ situations — that is, those that are associated with the object of the addiction — are removed, or if the length of time between their occurrence is made considerably longer. Moving to a neutral area, not associated with the addiction, can help and is worthwhile, but not always realistic. New activities, habits, and routines to fill the vacuum left by the object of the addiction are enormously important.

Yet such radical life changes are not easy — and they are rare. In addition, they are often incompatible with the life habits of the addict. A computer specialist who is addicted to the internet can’t simply avoid computers, since that would rob him of his livelihood. In such a case, the aim must be to restore the computer to the position of simple working tool. The only allowable association must be: computer = work, and not: computer = pleasure. This necessarily means that such a person must find another way to relieve stress, occupy his free time, and provide pleasure. A difficult task, but not impossible. At least the brain possesses the necessary plasticity to achieve it.

Can wanting be extinguished?

With this in mind, would it not be better to curb the wanting before it reaches the excesses of addiction? Buddhism is well-known for advocating this, its ultimate aim being the extinction of the will in the form of nirvana — the state in which there is no desire, no attachment, and no self-centred activity.

In western philosophy, the main proponent of this position was Arthur Schopenhauer. His philosophy was that life is eternal suffering and that this is the fault of the will, or of ‘wanting’, affecting the deep unconscious. This is because it is wanting that sparks any action in life, any interest we have, our wish to eat and drink, to desire each other and reproduce, to dominate and demean each other. The will is always desirous of fulfilment, and as long as we do not achieve that fulfilment, we will feel pain, which Schopenhauer also sees as including the feeling of being driven, which becomes stronger the more the will is forced to struggle against resistance. However, if the object of fulfilment of the will is achieved, it will not be long before we are overcome with boredom, until the wanting re-emerges, and the whole process begins again from the start. Thus, pain, lack of freedom, and boredom are the substance of existence, which is why Schopenhauer claims, ‘Every life story is a story of suffering’. This may sound pessimistic, but I believe Schopenhauer would have felt vindicated by the findings of modern brain science.

The same excitation curve of the mesolimbic dopamine pathway as described for drug addicts is seen in healthy individuals in a less pronounced form. It also rises rapidly before an aim is achieved, only to level off sharply once that objective is attained. We know that Parkinson patients who are no longer receiving dopamine agonists suffer similar symptoms to an alcoholic who is no longer getting anything to drink, and the basic principle is true of healthy people, too. When healthy individuals want something, they often become rather nervous and preoccupied, focusing their attention on how to attain the object of their desire. Once that goal has been achieved, they experience a brief moment of fulfilment, only to become despondent soon after. Self-doubt and depression set in, the previously driven and driving desire gives way to sadness and resignation. This cascade of suffering, fed by the activities of the dopaminergic system, sounds decidedly Schopenhauerian.

Incidentally, Schopenhauer would presumably have had no problem with his philosophy finding support in the results of modern brain research; after all, it was he who said, ‘Just as for the motion of a ball upon impact, so also ultimately for the brain’s thought, a physical explanation must be in itself possible’.

However, Schopenhauer was not a total pessimist; he did recognise opportunities to escape the eternal tribulation caused by wanting. He completely ruled out suicide, since that is a decision driven by the will. In fact, when people are treated for depression, either with drugs or psychotherapy, and initial signs of success begin to appear, that is often when they kill themselves. The initial treatment succeeds in awakening their previously dulled will, giving them the energy they previously lacked to go through with suicide. According to Schopenhauer, the preferred aim must be to extinguish the will, like snuffing the flame of a candle.

Schopenhauer saw one way to achieve this as being through art, by viewing the world from the standpoint of the artist, which should be disinterested and therefore liberated from will. A flautist himself, the philosopher considered music in particular to be an instrument of such deliverance, because in music we experience not things, but the will itself directly, allowing us to transcend the level of the objectifying want altogether. This theory is underpinned by the fact that research into addiction has never been able to identify an addiction to music as such. For sure, many musicians are workaholics or drug addicts, but this is more likely a consequence of the high-pressure industry they work in, as well as the narcissistic and psychopathic tendencies of many star performers. All those people who continually expose themselves to sounds through their personal stereo, smartphone, radio, or television could be described noise addicts, since they cannot stand silence around them. However, music itself appears to have no addictive properties.

According to Schopenhauer, other opportunities for deliverance from wanting are offered by self-denial and by compassion. Self-denial, as a way of breaking the power of wanting; compassion, to overcome one’s own, subjective suffering through empathy with the suffering of others. The Hungarian-American psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi would presumably include his notion of ‘flow’ (also known as ‘the zone’) — in which a person performing an activity is fully immersed in a feeling of energised focus — as one of the vehicles of deliverance from wanting. When we are immersed in an activity, the actual goal of the activity fades into the background as the activity itself takes centre stage. Or, expressed in Schopenhauerian terms: the will is extinguished because it no longer has any purpose on which to focus. Anyone who has ever lost track of time while out walking, while painting, or even while gardening, will know this to be true.

So there are many different ways to extinguish the will and the suffering it causes. And I can add to the list one more — rather surprising — way, which Schopenhauer could never have imagined. And that is where this book comes full circle.

The nirvana of locked-in syndrome

If there can ever be a description of the nature of the brain, then it must be this: the brain wants to achieve an effect, and the effect triggers the wanting. But what happens when the brain can no longer achieve any effects? When it no longer has access to the muscles and other organs of the body in order to set anything in motion — as is the case with locked-in patients?

For most people, the idea of being trapped in their own body is catastrophic, and can lead to nothing but despair. The reason for this is that we are creatures driven by will and so we cannot imagine the life of a locked-in patient from any other point of view. We see the totally paralysed patient lying in bed, being artificially ventilated, and feel only pity for that person and fear of ending up in the same position, because such patients are unable to do any of the things that people normally do. They cannot eat or drink, they cannot talk, they cannot even breathe unaided. If they want to raise their arm, or even just a finger, they cannot, because their body is as unresponsive as a corpse.

That sounds like something out of a horror film, and, indeed, a person who wants to do something but is suddenly unable to do it will undoubtedly suffer terribly at first. When a motorcyclist wakes up after an accident to find he is paralysed from the shoulders down, he will initially be aghast and horrified. However, the reason for this is that to him it seems that, only seconds before, he was in full possession of his ability to move and so he has had no time to become accustomed to his paralysed state. He lives in hope (for which read: will) of regaining his ability to move.

But what about someone who has come to terms with their condition and abandoned any hope that it will change in the future? This is precisely the case with many locked-in patients: with time, they no longer rebel against their fate, becoming accustomed to and accepting their paralysis, sure in the knowledge that they will almost certainly never recover. In the truest sense of the word, they are hopeless, without hope, which Zen Buddhism teaches can lead to a life full of peace, joy, and compassion.

Laboratory experiments have shown that lower lifeforms cease any activity that no longer produces an effect.19 No matter how much they are stimulated, they no longer respond. Their will to engage in that activity is extinguished even though, physiologically speaking, they would still have the energy available to perform the action. And this is no less true for the complex neuronal structure of the brain.

From an evolutionary point of view, this makes complete sense. Why expend energy and resources when there is nothing to be gained from it? Nature’s rule is: investments must pay off — and if an effect can no longer be achieved, then it is better to save the energy and stop investing resources.

We recognised this tendency in our locked-in patients. We had to use various ‘tricks’ and technical wizardry to rouse them out of their state of inactivity so that we could communicate with them. But does that mean they were unhappy?

Although we found barely any sign of will in the brain activity of our patients, we also found no indications that they felt miserable or desperate. We saw nothing of the withdrawal typical of addicts or anyone with a passionate want for something. Their brains also did not resemble those of people with depression, who see no point to their actions, because they expect only negative effects, and suffer as a result of this. The reason for all this is that locked-in patients do not suffer, because they have lost both the possibility to engage in any action and the expectation of negative results.

When we managed to make contact with our locked-in patients, they turned out to be happier than the average, healthy population. However, that was at a point when they were finally able to communicate, and so such a metric should not be afforded too much significance and should not be assumed to apply to patients who remain cut off. However, it does seem to be a strong indication that locked-in patients, in their own special way, have arrived at that ‘absence of will’ proclaimed by Schopenhauer and by Zen Buddhists to be deliverance from the tribulations of life: free of any feeling of being driven and free from any feeling of withdrawal.

What really goes on inside these people is something we may never know. Perhaps they inhabit a dream world, akin to daydreaming during a long train journey, when the driver and the tracks take over all responsibility for targeted motion. Maybe their thoughts are similar to those of meditating yogis. It would certainly be interesting to compare the brain activity of someone immersed in meditation and someone with locked-in syndrome.

I have now moved into the realms of speculation, since we have not yet managed to prove that completely locked-in patients are in a state of will-less bliss. And perhaps that is a good thing, since otherwise, some people might want to enter this state deliberately.

However, our results, as described in this book, are enough to persuade us to become more cautious. They show that we should not make judgements about the happiness or otherwise of a person who is no longer capable of wanting, from our point of view as creatures driven by will. The call for such patients to be ‘switched off’ and for them to ‘decide for themselves about life and death if it comes to it’ and for legally binding living wills — though they were drawn up when the signatory still had the capacity to want — are all nothing more than proof of a lack of an ability to imagine ourselves in such a different situation. We cannot completely exclude the possibility that even completely locked-in and severely injured patients can still find happiness. There is more evidence indicating that this is the case than that it is not. Our brains are capable of anything — even doing nothing.