Rain had now been falling for nine days in a row. Professor Albert had every window in the house open so he could smell it. The drops splashed through the window screens onto Kona’s brown nose and into Gwendolyn’s sparkling blue pool.

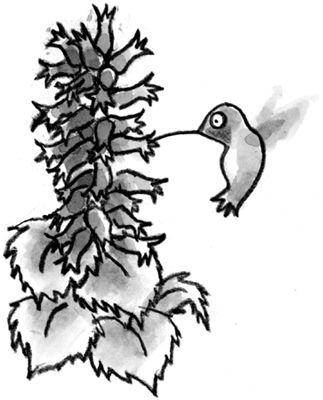

Everything had started growing again. Bright green needles were sprouting on the pines, and even the hydrangea bushes—which everyone had thought were long gone—had lifted up and produced tight, round, tiny balls of pink and blue flowers. Earthworms pushed up through the wet brown soil of all the yards and gardens, and even hummingbirds were sipping from the salvia again. Spiders wove strands of silk glistening wet with chains of pearls. Basements even flooded a bit; but fortunately for Kona and his friends, the basement in Professor Albert’s house stayed nice and dry, all the Christmas decorations still safe, and Murray’s stash of cheese curls tucked into the angel tree topper still crispy.

When Stan the Weatherman had finally predicted rain, almost a month had passed since the Night of the Owls (as everyone now liked to call it), and Kona and Herman and Gwendolyn had started worrying they might need a Master Plan Part Two. But they didn’t after all.

Still, the drought was sure to be remembered by everyone for a long time. Already flower beds in the Town Square that had not survived the heat had been replaced by little cacti and succulents, which needed hardly any water.

“Those are called ‘hens and chicks,’ ” Stumpy explained to Murray as they explored the square one evening to see the changes.

“Ohh, I see them!” said Murray. He pointed to a large, round succulent in what used to be the petunia bed.

“There’s the hen,” he said.

Stumpy nodded.

“And all those little ones are the chicks,” said Murray.

“I think we should name them,” Murray said.

“Murray, you want to name everything,” said Stumpy.

“Let’s call the hen Fluffy,” said Murray.

“Oh, for goodness’ sake,” said Stumpy.

Flower beds were, of course, not the only things that changed when the drought finally ended. Many people up and moved away, and so did many animals. It had all been too much. A lot of them headed for the rain forest in Olympic National Park.

But not Professor Albert. Not Kona and Gwendolyn. Not Stumpy and Murray and Top and Bottom and Sparrow. Not Herman.

This was their home. They loved it here. They couldn’t imagine being anywhere else or with anyone else. They wanted to stay.

And Morton.

Morton had been a wanderer for almost all of his life, and he had never known what it is to remain in place and watch the seasons come and go year after year, to watch children grow up, to watch old houses weather and fade, to watch saplings grow into maple trees.

Morton had been Murray’s long-lost brother in more ways than one. Because Morton had actually, at times, felt lost. As if he did not know where he belonged. And belonging is so important for anyone. If someone ever asked Gwendolyn what the grayest time of her life was, she always said it was the two months she spent in a bowl in the pet shop. This was because, she said, she belonged to no one. Gwendolyn said that it was a good experience, though, because ever after, she understood everyone who felt lost, and she could promise that one day, if they were patient and trusting in Life, they would find where they belonged.

And so the drought, and all of the hardship and worry it had brought to everyone in Gooseberry Park, turned out to have what is called a silver lining for a certain long-lost brother who had grown weary of fancy thoughts and fancy language about how to achieve a successful life.

What Morton really wanted, he discovered, was someone nice to eat dinner with every day. So he found a little birch tree near Stumpy and Murray’s sugar maple.

And he unpacked his Zen cookbook.

And he stayed.