He nearly killed me with his black tobacco.

PADDY DONOVAN, Orwell’s comrade in the Aragon trenches

The above title should have a parenthesis ‘with apologies to Simon Gray’. It was Gray who, in one of the great comic works of the last half-century, identified the essence of his being in the cigarettes he dragged on. I smoke, therefore I am.

Cyril Connolly recalls visiting Eric Blair in his room at Eton, reposing coolly among ‘a litter of cigarette ash’. Doubtless there was an overflowing ashtray in the hospital room where he died. In the notes for novels he might, if he lived, write alongside his bed in UCH was one provisionally called ‘Smoking Room Story’. It could be the story of George Orwell’s life.

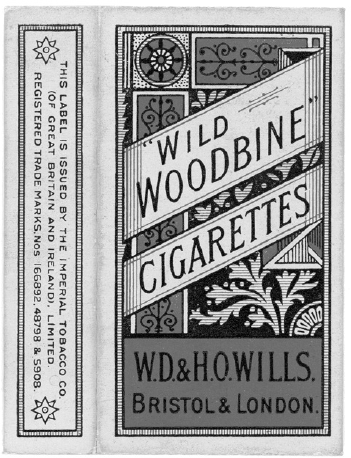

It is not recorded when Orwell had his first drag. Like one’s first lover’s kiss, he himself would have known. It was when he was very young, in Henley, one guesses. And furtive – a ‘behind the cycle sheds’ kind of thing. By the time he got to Eton, he had what would be a lifelong ‘habit’. His taste, and the kind of cigarette he favoured, changed over the years. When hard up, he went for the working-class standby, ‘Wild [“Willy”] Woodbines’ (a year’s use, he calculated, could be had for £40). The name ‘Wild Woodbine’ contained a literary allusion, and Orwell must have been one of the few of the puffers who recognized and relished it: ‘I know a bank where the wild thyme blows, Where ox-lips and the nodding violet grows; Quite over-canopied with luscious woodbine, With sweet musk-roses and with eglantine’ (A Midsummer Night’s Dream). In his down-and-out period, in Paris and London, he developed a taste for harsher, ‘foul-smelling’ roll-ups. He would be loyal to Gallic ‘black shag’ tobacco for life. It fascinated the children he taught, in his school-teaching year, that he had learned in Paris how to roll a cigarette single-handed.

As foul as his roll-ups was the stench of the places Orwell visited in this down-and-out phase of his life. The following, for example, is from ‘The Spike’:

In the morning they told us we must work till eleven, and set us to scrubbing out one of the dormitories . . . The dormitory was a room of fifty beds, close together, with that warm, faecal stink that you never seem to get away from in the workhouse . . . These workhouses seem all alike, and there is something intensely disgusting in the atmosphere of them. The thought of all those grey-faced, ageing men living a very quiet, withdrawn life in a smell of w.c.s, and practising homosexuality, makes me feel sick. But it is not easy to convey what I mean, because it is all bound up with the smell of the workhouse.

Tobacco would have to be super-foul to beat that.

Around the time that he went down and out, Orwell began to use the roll-up machines that became popular in the 1920s – and more so in the Depression years, when shop-bought packet cigarettes were out of reach for many. Even when he could afford ready-mades, Orwell liked the working-class statement that rolling your own made, as he liked drinking his tea from the saucer in the BBC canteen. It made a point.

Josh Indar has written an authoritative survey on Orwell’s ‘smoking obsession’.1 His dabbling, for example, with ‘green cigars’ in Burma. There are 41 references, Indar calculates, to smoking in Down and Out in Paris and London, and the characteristically Orwellian comment, ‘It was tobacco that made everything tolerable.’ As a tramp, doubtless he picked up and smoked – along with Paddy – ‘dog ends’. Part of the tramp’s constant battle with authority was preserving a tobacco stash from the strip-searches when entering the spike. ‘We would’, writes Orwell, in his notes for Down and Out,

[smuggle] our matches and tobacco, for it is forbidden to take these into nearly all spikes, and one is supposed to surrender them at the gate. We hid them in our socks, except for the twenty or so per cent who had no socks, and had to carry the tobacco in their boots, even under their very toes. We stuffed our ankles with contraband until anyone seeing us might have imagined an outbreak of elephantiasis.

Note the ‘we’: smoking, and its paraphernalia, was one of the few things that put the Etonian on equal terms with the working-class man – symbolized by the pseudo-handshake of the ‘offer’. If you couldn’t smoke, you’d put it ‘behind your ear’, because your turn to offer would, in time, come.

In Keep the Aspidistra Flying, Gordon Comstock comes close to nervous breakdown with only four ciggies to last him till payday. His brand is Gold Flake, with their distinctive canary-yellow packet. When ‘short’, however, he has to make do with Player’s Weights (poor relative of the ‘Player’s Please’, which were not quite so proletarian), so called because they were originally sold by the weight, not the number. The second paragraph of Aspidistra is one of tobacco-addiction torment:

The clock struck half past two. In the little office at the back of Mr McKechnie’s bookshop, Gordon – Gordon Comstock, last member of the Comstock family, aged twenty-nine and rather moth-eaten already – lounged across the table, pushing a four-penny packet of Player’s Weights open and shut with his thumb.

He has four cigarettes left, and no money to buy a new supply for two days. ‘Tobaccoless’ hours stretch before the ‘last member of the Comstock family’.

In Homage to Catalonia, tobacco is recorded by Orwell as being one of the five things a soldier in the trenches cannot live without. To paraphrase Napoleon, an army marches on its lungs. At a very low point the POUM ration sinks to five a day. The first thing Orwell did, on recovering from being shot in the throat, was ask his nurse for a cigarette. He writes:

I wonder what is the appropriate first action when you come from a country at war and set foot on peaceful soil. Mine was to rush to the tobacco-kiosk and buy as many cigars and cigarettes as I could stuff into my pockets.

George Bowling, in Coming Up for Air (between puffs, presumably), smokes cigarettes and, when he is feeling good, cigars, like the proverbial chimney. He had an early taste for Abdulla: ‘the one with the Egyptian soldiers on it’.

As a mark of his new bipedality, the former pig smokes a pipe in Animal Farm. And most readers, particularly smokers who roll up, recall Winston Smith, in the first chapter of Nineteen Eighty-Four, forgetting to keep his wretched Victory cigarette upright, and the tobacco tipping out on to the floor.

Cigarettes were one of the things that kept the British sane during the Second World War. In his essay ‘Books vs. Cigarettes’ of 1946, Orwell calculates that he smokes six ounces of Player’s tobacco a week, spending £40 a year to sustain the habit, £15 more than he spends on reading material. If most hand-rolled cigarettes contain about a gram of tobacco each, Orwell must have smoked close to 170 cigarettes a week, a little more than a pack per day. Empson, working alongside Orwell in the BBC, found the aura of ‘shag’ he generated ‘disgusting’. But, he notes, it was preferable to the body odour of Orwell himself. J. J. Ross, the author of Orwell’s Cough, concludes: ‘A heavy smoking habit probably also contributed to his gaunt appearance.’

Gauntness was the least of it. Orwell was prepared to undergo crucifying treatment for the lungs he was abusing. And still smoke – even after he was diagnosed, authoritatively, with TB, in 1947. Hilda Bastian notes that

Orwell had been given treatments that were common for tuberculosis in Britain at that time: ‘collapse therapy’ and other painful surgical procedures to keep the lung disabled to ‘rest’ it, vitamins, fresh air, and being confined to bed. The hospital staff confiscated his typewriter and told him to stop working – but they didn’t seem to advise him to stop smoking!

Why did Orwell smoke so self-destructively? He was addicted, of course. But also, I think, he smoked for tobacco’s deodorizing effect, and his morbid sensitivity about his own bodily smell. And, of course, because he loved the smell of tobacco.