It would be hateful if things did not smell: they would not be real.

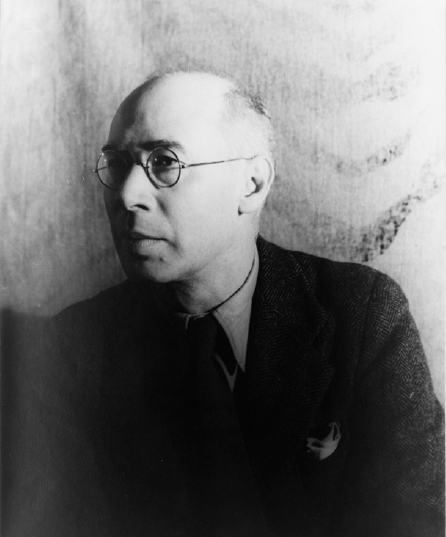

ADRIAN STOKES

Three years ago, in high hay-fever season, I lost my sense of smell. It has never returned and I’m told it never will. Of all the five senses one can expect to part with en route to sans everything, smell is the most dispensable.

And if the Freudians (and Jonathan Swift) are right that civilization is the distance Homo sapiens (‘Yahoos’) puts between his nose and his excrement, I am a more civilized person for living in my organically neutralized world. The 94 per cent of British adult women and 87 per cent of British men who use deodorants daily would perhaps agree. (These figures, taken from the Internet, seem high to those I’ve spoken to with the power of smell. Particularly on homeward journeys on the London Tube.)

About the same period that my nasal membranes wilted I had embarked on a reread of Orwell, in the spirit of Janeites who revisit Austen’s six novels every year, just to relax into the comfort of old literary places. The writings I had known for half a century were, I found, interestingly different. Not quite as comforting. Imagine, for example, a person born with no sense of smell. Would Animal Farm ‘read’ the same way as for someone with functioning nostrils and long familiarity with the richly mixed but detectably different aromas (cow shit, chicken shit, horse shit, pig shit) in a farmyard? And then, at the end, Napoleon walking past on two legs with – what else? – an aromatic cigar.

According to Norman Mailer, a fellow connoisseur, with Orwell, of life’s olfactions (or, as Mailer would call them, ‘olfactoids’), there ‘ain’t but three smells’ in the whole Hemingway oeuvre. Papa’s fish, to adopt the working-class insult, don’t smell. Mailer’s count, thrown out, as I recall, on the Dick Cavett talk show, was not the result of careful textual examination but nonetheless rings true.

Compare the first three richly scene-setting aromas in Nineteen Eighty-Four. The story opens with Winston Smith escaping the April cold through the glass doors of Victory Mansions. Instant nasal attack: ‘The hallway smelt of boiled cabbage and old rag mats.’ Having slogged up to his apartment on the seventh floor (the lift, of course, is broken), Winston pours himself a reviving swig of Victory Gin. ‘It gave off a sickly, oily smell, as of Chinese rice-spirit.’ He smokes a Victory cigarette (no need to describe that acrid smell), and is called to the Parsons’ flat next door. Can he unplug the sink? begs the harassed mother:

There was the usual boiled-cabbage smell, common to the whole building, but it was shot through by a sharper reek of sweat, which – one knew this at the first sniff, though it was hard to say how – was the sweat of some person not present at the moment.

You need a nose that a bloodhound would envy to track the perspiratory reek of someone who has been out of the house for hours. Later, in the grim waiting room for the dreaded Room 101 trip, Winston is obliged to smell, at close range, Parsons’s shit while it is still warm and at its most odoriferous. Horrible as it is, it is preferable to the smell that awaits Winston in Room 101.

There are many threads in Orwell’s fiction. But it is interesting to compile their ‘smell narratives’. I append one for A Clergyman’s Daughter, along with the most smell-referential of his non-fiction books, The Road to Wigan Pier. The latter contains the four words that have hung like an albatross around Orwell’s neck: ‘The working classes smell.’ The qualifications with which he surrounded the allegation are rarely quoted.

Smell narratives would be as terse as a 140-character tweet with some authors. I asked Deirdre Le Faye, the doyenne of Jane Austen studies and editor of her surviving letters, what smells there were in the six novels. Deirdre’s reply was interesting and perplexed:

Smell I think is only specifically mentioned in Mansfield Park, with the bad air and bad smells of the Portsmouth house. This does strike me as slightly odd, because by our standards at least, the past must have been a fairly smelly place.

The ‘lady’ who wrote Sense and Sensibility was, apparently, short of one sense.

What would the ambient smell of Jane Austen’s outside world have actually been? Easily answered. Inside the house, the communal toilet sand box. Outside, horse droppings, predominantly – whether in rural Hampshire or urban Bath. The Regency world moved on four legs. Horses deposit between 7 and 14 kg (15 and 30 lb) of excrement and 9 litres (2 gallons) of urine per day where they will. There is no such beast as a house-trained horse.

Orwell, who claimed he would have preferred to have lived two hundred years ago, with his fellow ‘Tory-anarchist’ Jonathan Swift, might have found that equine-excremental world more bearable, attractive even, than the world he was born in. He loathed twentieth-century mechanical smells – although paraffin (his commonest source of home heating and lighting, when in the country) he found oddly ‘sweet’ to his nostrils, probably because of its association with warmth and light. More than most twentieth-century authors, he did a lot of reading and writing by tilly lamp, the odoriferous heater meanwhile throwing its mottled pattern onto the ceiling.

One of Orwell’s perceptive observations in his 1946 essay ‘Politics vs. Literature’, on his most admired author, Swift, is that in Gulliver’s Travels the morbidly naso-sensitive hero finally accepts as his ideal the horse, ‘an animal whose excrement is not offensive’. It is a ‘diseased’ choice on Swift’s part, Orwell grants. But Gulliver’s first experience when he arrives in Houyhnhnmland is to be spattered with human shit. Of the two varieties, which would one prefer? Orwell was, whenever the opportunity came up, a smallholding farmer: horse shit he valued (there are diary entries recording him examining minutely the quality of recent droppings) as fertilizer. Pig shit (he hated the omnivorous pig) was useless for that purpose.

Human excrement, like that of other carnivores, is offensive. Herbivores and graminivores, like the horse and goose (an animal Orwell loved and kept, whenever he could), have inoffensive excrement (when walking in Regent’s Park I have to prevent my dog from eating that variety of animal dropping. Dog shit does not attract her).

Not that it’s relevant, but I’ve often wondered where vegan droppings would stand on the Orwellian offensiveness scale. But Orwell despised ‘sandal-wearers’ and ‘fruit-juice drinkers’ as cranks, and they would not have attracted his nasal interest. He despised, as he told his working-class friend the aptly named Jack Common, ‘eunuch types with a vegetarian smell’.1

The reasons Orwell, ruinously for his health, spent the best years of his adult life in Burma, are hard to disentangle. But one was surely the call of the nostalgic curries, and the fading but still pungently mingled scents of sandalwood, rattan and teak (the most long-lastingly odoriferous of woods) in the Anglo-Indian house he was brought up in. He could not, joked his friend the critic Cyril Connolly, ‘blow his nose without moralising on conditions in the handkerchief industry’. Or sniff, one suspects, his mother’s vindaloos and chutneys, without wondering about the subcontinent and the ethics of colonialism.

There were indeed intoxicating aromas to be found in Burma for a young man. And if Orwell’s description of his hero, John Flory’s, lovemaking in Burmese Days is to be trusted, erotic nasal stimulus was a major part of the oriental package. Flory, as he embraces his house concubine, Ma Hla May, is aroused: ‘A mingled scent of sandalwood, garlic, coconut oil and the jasmine in her hair floated from her. It was a scent that always made his teeth tingle.’ Tingling teeth is a fine detail. And it is not metaphorical. The trigeminal nerves connect nasal and dental sensation. The English working class (as Orwell would have overheard many times) glorify the ‘knee trembler’ (sex, faute de mieux, standing up, in an alley – Orwell describes it in The Road to Wigan Pier). Tooth tinglers are less common with the cold wind whipping round your bare ankles – damned uncomfortable, but relatively smell-less.

Compare aromatic Burmese copulation with the whiffiness of the whore Winston Smith recalls using in Nineteen Eighty-Four:

He seemed to breathe again the warm stuffy odour of the basement kitchen, an odour compounded of bugs and dirty clothes and villainous cheap scent, but nevertheless alluring, because no woman of the Party ever used scent, or could be imagined as doing so. Only the proles used scent. In his mind the smell of it was inextricably mixed up with fornication.

Whorish filth, for Orwell (who is known to have used common prostitutes at various stages of his adult life), was as powerful as sandalwood. It too ‘allures’, like the rotten apple that Schiller kept in his desk drawer to revive his literary inspiration when it flagged. Fresh apples don’t get the teeth tingling.2

Orwell’s discrimination of the sniff reaches a pitch of sheer nasal virtuosity, as in the following, ascribed to George Bowling, on one of his time trips back to Sundays in his childhood Lower Binfield (Orwell, of course, is describing the church of St Mary he attended, as a child, in Henley-on-Thames):

How I could smell it! You know the smell churches have, a peculiar, dank, dusty, decaying, sweetish sort of smell. There’s a touch of candle-grease in it, and perhaps a whiff of incense and a suspicion of mice, and on Sunday mornings it’s a bit overlaid by yellow soap and serge dresses, but predominantly it’s that sweet, dusty, musty smell that’s like the smell of death and life mixed up together. It’s powdered corpses, really.

In his essay on Swift, ‘Politics vs. Literature’, Orwell rhapsodizes on ‘the gloomy words of the burial service and the sweetish smell of corpses in a country church’.

Biographers are sometimes surprised that Orwell, who claimed to have embraced atheism aged fourteen, should have insisted on being buried in a country church rather than the ‘sanitary’ option of cremation. He wanted, one surmises, to leave the world accompanied by his personal decaying smell as he had entered it, inter urinas et faeces.

Only the proles used scent.

Adrian Stokes, in his curious essay ‘Strong Smells and Polite Society’,3 notes that for the English ‘decent’ classes all smells are bad smells. Particularly those emanating from the human (sweating, perspiring or, with ‘ladies’, glowing) body.

And what Stokes (an artist who chose to live the life of a peasant) calls, with an irrepressible patrician sneer, ‘politeness’ entails suppressive cultural inhibition. The English have, with a sense of national self-righteousness, never developed any aesthetic cultivation via the nose. For the French, by contrast, the pleasure of the ‘bouquet’ is an essential preliminary to the enjoyment of wine or liqueurs. The French value an ‘art’ of smell. Watching a Frenchman drink a fine vintage, and his British counterpart down a pint of bitter, is a lesson in national difference.4

Suppression of smell is, for the British since the puritan revolution of the seventeenth century, ‘moral’. Even cultural revolutionaries find it difficult to shake off this nasal puritanism. D. H. Lawrence, for example, fought valiantly, in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, to liberate four-letter (‘dirty’) words for writers’ creative use – fuck, arse, shit, piss. ‘Hygienising’, he called it. There is one four-letter word not on the liberated Lawrentian lexicon – ‘fart’. It is beyond hygienization. Why? Because as Richard Hoggart insisted in the 1960 trial (to the shattering discomfiture of the prosecution), ‘Lawrence is a puritan.’ And in that silence about flatulence one hears, distantly, his evangelically inclined woman, immortalized as Mrs Morel, saying, ‘No, please no Bert; that word is so vulgar.’

Orwell did not read Ulysses until 1933, when his cosmopolitan lover, Mabel Fierz, smuggled him, at the risk of both their prosecutions, a copy of Joyce’s prohibited book. Among the legally offensive passages was the description of Bloom ‘asquat the cuckstool . . . seated calm above his own rising smell’. Joyce, of course, wrote the bulk of Ulysses in France.

The flatulent virtuosity of ‘Le Pétomane’, the French artiste du fart, could, one feels, have originated nowhere but at the Moulin Rouge where Joseph Pujol, as a rousing finale, would nightly ejaculate an anal Marseillaise. In English theatres and cinemas, it was ‘God Save the King’. Standing to attention, buttocks decently clenched.

Orwell’s obsessive relationship with smell created odd cultural comradeships: principally with Swift, Salvador Dalí (the one artist he wrote an essay on) and Henry Miller.

His decades-long fascination with the author of The Tropic of Capricorn is, on the face of it, odd. It was not a casual thing. One of the few times Orwell fell foul of the law was for illicitly having a smuggled collection of Miller’s Paris-published oeuvre. He wrote about and referred to Miller many times, and went out of his way to visit him. What principally drew him was not the ‘pornography’ (as then defined – Miller is now an American classic) but the sensory extravaganza on interesting French stench, from the gripping second sentence of the first tropic onwards: ‘Last night Boris discovered that he was lousy. I had to shave his armpits and even then the itching did not stop.’

As Orwell wrote, in his first tribute piece to Miller, he creates a Paris permeated with:

the whole atmosphere of the poor quarters of Paris as a foreigner sees them – the cobbled alleys, the sour reek of refuse, the bistros with their greasy zinc counters and worn brick floors, the green waters of the Seine, the blue cloaks of the Republican Guard, the crumbling iron urinals, the peculiar sweetish smell of the Metro stations, the cigarettes that come to pieces, the pigeons in the Luxembourg Gardens.5

More specifically, the smell of it. Orwell found in Miller the most congenial nasal Francophile. A brother of the nose. The company of Cyrano.

Outside the whale. Henry Miller, Orwell’s idol.

One seemed always to be walking a tight-rope over a cess-pool.

Orwell was born with a singularly diagnostic sense of smell. He had the beagle’s rare ability to particularize and separate out the ingredients that go into any aroma. One memorably odoriferous passage, never forgotten by anyone who has read the account (‘Such, Such Were the Joys’) of Eric Blair’s (as he then was) awful prep school, describes the ablution ordeal that the pupils had, daily, to endure at St Cyprian’s. It centred on ‘the slimy water of the plunge bath’:

and the always-damp towels with their cheesy smell: and, on occasional visits in the winter, the murky sea-water of the local Baths, which came straight in from the beach and on which I once saw floating a human turd. And the sweaty smell of the changing-room with its greasy basins, and, giving on this, the row of filthy, dilapidated lavatories, which had no fastenings of any kind on the doors.

The ‘cheesy smell’ of the towels? An odd adjective, one might think. But it’s not. The ‘aromatographer’ (not, one suspects, a crowded specialism) Avery Gilbert has devoted himself to ‘olfaction – the strange and wonderful world of smell’. He offers a precise analysis (as Orwell’s is a precise description) of the exclusive masculinity of the cheese-on-towels smell. In a recent study,

researchers . . . spent three winters collecting droplets of fresh sweat from volunteers in the sauna. It turns out that women have far higher amounts of the MSH precursor than do men, which means women (or rather the bacteria that love them) can liberate significantly more of the sulfur volatiles that smell like tropical fruit and onions. Male BO, in contrast, tends to smell cheesy and rancid.6

That gender-distinct odour is something that only a nasal virtuoso would pick up on. Orwell qualifies as just such a virtuoso of the nostril.

For eight-year-old Eric Blair, St Cyprian’s was a traumatizing culture shock, beginning with the affront to his young nose. It was not a wholly English nose, which was a major part of the problem.

Eric Blair was half French. He was brought up by a French mother in the expatriated absence of his English father, in his formative first seven years of life. The Blair household, by the Thames, was, behind its walls, as Gallic as a household along the Loire. His essential Frenchness was efficiently camouflaged in later life by an ultra, almost theatrical, English carapace. Close friends, such as Anthony Powell, saw through it. For those not close to him he was as ‘English’ as the legendary Major Thompson (played by Jack Buchanan in The French, They Are a Funny Race, 1955).

Orwell’s ‘toothbrush’ (pubic hair of the upper lip) and unflowing locks (‘short back and sides, please’ – in later life he would perform it himself with kitchen scissors) were the kind uniformly adopted by young English men in the early twentieth century, to proclaim that they were no Oscar Wildes (Francophile and worse). ‘Nancies’? Orwell despised them, viz. the (outrageously homophobic, by today’s standards) opening chapters of Keep the Aspidistra Flying. The ‘tash’ also served as a barrier between the nose and the smelly world outside.

Photographs bear out the fact that no great author was less the dandy than George Orwell. A cadaver with suits that hung like an unwashed shroud is the usual verdict of friends such as the dapper Malcolm Muggeridge. Gordon Bowker notes amusingly that in his Jura period Orwell actually carried a scythe and shotgun around with him – looking like something out of Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal. But as a small and rather touching filial tribute he chose poodles, the dandy’s pooch, as his favoured domestic pet (his mother, Ida, had bred them). One poodle, in later life, he called ‘Marx’ – the closest he ever got to reading Das Kapital, as Bernard Crick, never one to admire Orwell as a political thinker, sourly observes.

Maternal, Gallic influence meant that young Eric was wholly unacculturated to the nasal shocks of St Cyprian’s and their underlying ideological meaning. If there were a word that summed up the ethos of schools like the one his parents sent him to, it was ‘manly’. The above ‘plunge bath’, for example, would have been ‘bracingly’ chill. The testicle-shrivelling ‘cold bath’ or ‘shower’ is, for the English, a moral, not a sanitary thing. It forms ‘character’. In A Clergyman’s Daughter, the heroine, Dorothy, takes a cold bath at 5.30 every morning to purify her mind and tame her body. The English shiver into virtue. Warm baths, the pupils at St Cyprian’s would have been ritually warned, led to the downfall of the Roman Empire. No such fate should befall England’s dominions.

Nations, societies and groups founded on a bedrock of puritanism, like the UK and u.s., take up arms (up to the very armpits themselves) against smell, as militantly as Christians going to war. In the hazy picture that Christians traditionally have of the place, hell is horrifically odorous. Its smell (like rotting eggs but worse) is fearful. In an illuminating book, Why Hell Stinks of Sulfur: Mythology and Geology of the Underworld (2013), Salomon Kroonenberg traces our conviction that those of us condemned to suffer eternal damnation will have our noses punished, while devils go at our rumps with pitchforks, and the large worm feasts on us as the whim takes it.

Heaven (with all those freshly laundered white robes) is as odour-free as we would like our inconveniently odoriferous bodies to be. We spray every dubious carnal pit, hole and suspect warm place. Perhaps, we fantasize, the tiniest ‘fragrance’ is permissible ‘up there’ – the ‘odour of sanctity’, for example, which hovers over the rotting flesh of those destined for beatitude when mother church gets round to it (Orwell’s first – incense-laden – primary school was run by nuns).

Cosmic stink/fragrance merits a short digression. Orwell discovered Paradise Lost when he was sixteen. He read, in a small tutorial group at Eton, the whole poem aloud. ‘It sent’, he later recalled, ‘shivers down my backbone.’7 Another tingler.

Anyone who, like Orwell, knows the poem will recall how extraordinarily, and theologically, smelly it is. There is no mystery as to why Milton should have been so sensitized. He was blind and his other senses were sharpened in compensation. To take one of many examples, the following typically extended Miltonic simile describes Satan’s (the fiend’s) use of seductive odour (Milton, puritan that he was, did not approve of perfume. Or Satan):

now gentle gales

Fanning their odoriferous wings dispense

Native perfumes, and whisper whence they stole

Those balmy spoils. As when to them who sail

Beyond the Cape of Hope, and now are past

Mozambic, off at sea north-east winds blow

Sabean odours from the spicy shore

Of Arabie the blest, with such delay

Well pleased they slack their course, and many a league

Cheered with the grateful smell old ocean smiles.

So entertained those odorous sweets the fiend

Who came their bane, though with them better pleased

Than Asmodeus with the fishy fume,

That drove him, though enamoured, from the spouse

Of Tobit’s son, and with a vengeance sent

From Media post to Aegpyt, there fast bound.

(Paradise Lost, IV, 156—71)

There are no fewer than six different smells described in these dozen lines.

When, by contrast, in Book V the archangel Raphael comes to Eden to warn Adam and Eve, he shakes his wings and exudes a decently ‘heavenly fragrance’ – no deceptive Sabean odour or fishy fume.8

Smells, one agrees with Milton, are charged with religious significance. According to the Washington Post, over 90 per cent of Americans, adult and teenage, use deodorants as a gusset tribute to the puritan fathers of the nation. Most do so ‘religiously’ around the time when puritans would say their morning prayers. These applications are laboratory-designed to ‘kill’ smell – at source. They are also implausibly accused of killing their too-enthusiastic users. But a few cancers are, surely, a small price to pay for national odourlessness.

One can fancifully draw up a list of objects and rituals that define the cultural distance created by 21 miles of channel. The bidet; the caporal cigarette with its North African ‘bite’; the stale incense of the country church at noon on a hot day in Provence; the olive-oil tang wafting from the adjoining street café; the open street ‘pissoir’ on a warm night; the fragrance that, to this day, wafts with dry, offshore winds over the Côte d’Azur from Grasse; the ‘bouquet’ of its perfumeries; the mouth-watering aroma of café express and fresh croissant; the memory-stirring madeleine.

Only French culture could produce such triumphs of art nasale as Huysmans’ Le Gousset (in his Croquis Parisiens) – an extended rhapsody on the woman’s armpit: ‘no aroma has more nuances’ Research (there’s not much in this area) has discovered that it is maternal armpit odour that draws the baby to its food supply underneath.

To summarize: for the Americans, it’s purifying deodorant; for the French, enriching fragrance. For the English, as the German cynic von Treitschke put it, ‘soap is civilization.’ The ‘Great Unwashed’ is a very different concept from sansculottes or Lumpenproletariat or white trash. That ‘cleanliness is next to Godliness’ has been drilled proverbially into English children for centuries. The hope of resurrection requires a carbolic bar in one hand and the Bible in the other. Salvation is hinted at by the premier soap of Orwell’s day (and mine), ‘Lifebuoy’. sos. Soap saves souls.

In later life the rule is: ‘Working classes sweat, gentlemen perspire, ladies “glow”.’ Class and gender are subtly involved in our engagement with smell. And, of course, selfhood.

Most people enjoy the sight of their own handwriting as they enjoy the smell of their own farts.

W. H. AUDEN

Gordon Bowker argues that Blair/Orwell sought out ‘evil odours . . . as if to rub his own nose in them to exorcise his demons through self-inflicted suffering’. But there seems to be interest, and on occasion relish, in his fascination with smell.

One suspects that Blair/Orwell was of that sexual group of paraphiliacs for whom Freud could only devise a French term – renifleurisme; male erotic gratification from the covert sniff.9 Freud developed the theory and practice of the renifleur in his case study of the ‘Rat Man’ (an appropriate pseudonym for Orwell). Shoes and underwear are the two popular fetish objects for the active renifleur. Both, of course, must have been used, and must still reek with the spoor of their owner.

A relevant literary comparison comes to mind. Orwell, as has been said, was late coming to James Joyce – in 1933, as he was writing A Clergyman’s Daughter. He must have been struck by the idea that Joyce was as connoisseurial about sexual smell as he was. A ‘smell narrative’ of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man would be as lengthy as any novel of Orwell’s.

In Portrait, Joyce observes that smell is the primal sense the newly arrived human being uses to make sense of its extra-uterine environment. Freud calls this the ‘anal stage’. It is vitally important for the newborn child to recognize the smell of the milk-giver, and to clamp onto it. The autobiographical Portrait opens with little Stephen, two years old, ‘all ears’ under the table as his family argues. He thinks: ‘When you wet the bed first it is warm then it gets cold. His mother put on the oilsheet. That had the queer smell. His mother had a nicer smell than his father.’

It is a few years later that more complex sensory discrimination is cultivated. In his Swift essay, Orwell recalls the child’s ‘horror of snot and spittle, of the dogs’ excrement on the pavement, the dying toad full of maggots, the sweaty smell of grown-ups, the hideousness of old men, with their bald heads and bulbous noses’. It’s a little coming of age, and a toe-dipping plunge into the universal cesspit. The child, of course, whatever its dislike of the ‘sweaty smell of grown-ups’, has grown, over the years, to be fond of its own (‘my’) smells and treats them as treasured properties, privately and, usually, shamefully as it grows older. Hence Auden’s remark above about one’s own farts. Other people’s are mephitic.

James Joyce records the olfactory narcissism (‘my smell, right or wrong’) more indulgently than Orwell. There remained enough Catholic in the Irish writer to absolve himself of this little carnal indulgence. Most interesting in Portrait is the passage describing Stephen’s self-mortification, in his religiously fanatic period. He determines to bring ‘each of his senses under a rigorous discipline’. Sight and hearing are relatively easy. But

To mortify his smell was more difficult as he found in himself no instinctive repugnance to bad odours whether they were the odours of the outdoor world, such as those of dung or tar, or the odours of his own person among which he had made many curious comparisons and experiments.

His most intimate body odours are dear to him, because they are his own. But what is implied by ‘many curious comparisons and experiments’? It requires an inward holding of the nose to pursue that question.

Joyce, an unashamed coprophiliac (as, one can conjecture, was Orwell – hence his recurrent use of the word ‘faecal’), was driven to ecstasies of erotic excitement by female soiled knickers. He once disclosed that all he needed to come to climax was a sniff of his wife Nora’s underwear. In one of the famous ‘dirty letters’, he rhapsodizes,

The smallest things give me a great cockstand – a whorish movement of your mouth, a little brown stain on the seat of your white drawers, a sudden dirty word spluttered out by your wet lips, a sudden immodest noise made by your behind and then a bad smell slowly curling up out of your backside.

Joyce’s ‘dirty letters’ were not published until half a century after Orwell’s death.10 It’s interesting to speculate what the latter would have made of passages like the above. There might well have been fraternal sympathy.

When from a long-distant past nothing subsists, after the people are dead, after the things are broken and scattered, taste and smell alone, more fragile but more enduring, more unsubstantial, more persistent, more faithful, remain.

MARCEL PROUST, Remembrance of Things Past

Comparisons with the so-called ‘Proust Phenomenon’ (as psychologists call it) – temps perdus recovered via the smell of a teacake – are not out of place when discussing Orwell’s fiction. As his amiable ‘Tubby’ Bowling puts it in Coming Up for Air (we first encounter him in the family ‘lav’), the past is a very curious thing:

It’s with you all the time. I suppose an hour never passes without your thinking of things that happened ten or twenty years ago, and yet most of the time it’s got no reality, it’s just a set of facts that you’ve learned, like a lot of stuff in a history book. Then some chance sight or sound or smell, especially smell, sets you going, and the past doesn’t merely come back to you, you’re actually IN the past.

Science is as interested in the Proust Phenomenon as literature is. In what is claimed to be the largest ever investigation to date,

the National Geographic survey gave readers a set of six odours on scratch-and-sniff cards. From a sample of 26,200 respondents (taken randomly from over 1.5 million responses), 55% of respondents in their 20s reported at least one vivid memory cued by one of the six odours and this fell to just over 30% of respondents in their 80s, remarkable proportions with such a small number of odours.11

In his essay ‘Music at Night’ (1932), Aldous Huxley foresaw, with a shudder, cinemas of the future in which ‘egalitarians’ (Huxleyese for ‘proles’) will experience the total sensory barrage of ‘talkies, tasties, smellies, and feelies’. In the manuscript of Nineteen Eighty-Four Orwell also played with the idea of ‘smelloscreens’. Roll on, say I. Orwell and Joyce will be rich sources for this madeleine for the people.

To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.

ORWELL (1946)

Orwell’s socialism is a battleground, best avoided by those who do not wish to find themselves in a slough of hot-tempered tedium. One thing one can safely say is that his political thought is commonsensical and that the Orwellian ‘smell test’ is central to it. Who but Orwell would diagnose the current (1936) malaise of socialism nose-first, as a malodour? ‘Socialism, at least in this island, does not smell any longer of revolution and the overthrow of tyrants; it smells of crankishness, machine-worship, and the stupid cult of Russia. Unless you can remove that smell, and very rapidly, Fascism may win.’12 It is hard to think of it inspiring a rousing call (‘We Must Reform our Smell, Comrades!’) at the annual Labour Party Conference. But it is echt Orwellism.

Orwell trusted the ‘smell test’, and made crucial changes in his life on the strength of it. When he came back for good, after five years in Burma, ‘one sniff of English air’ confirmed that he had done the right thing. The nose knows. One inhalation, and he decided he was never going back.

Orwell was, elsewhere, raised to heights of mirthful satire by the odour of left-wing ‘crankishness’:

It would help enormously, for instance, if the smell of crankishness which still clings to the Socialist movement could be dispelled. If only the sandals and the pistachio-coloured shirts could be put in a pile and burnt, and every vegetarian, teetotaller, and creeping Jesus sent home to Welwyn Garden City to do his yoga exercises quietly!

The money stink everywhere

Keep the Aspidistra Flying

Another kind of socialism – which Orwell repudiated more angrily – was the hypocritical, silk sheets, variety. There is a telling episode in Keep the Aspidistra Flying. Gordon Comstock (a ‘moth-eaten’, short-arse, prematurely burned out, talentless, self-punitive caricature of Orwell himself) bullies his rich magazine-proprietor friend and patron, Philip Ravelston, into accompanying him into a working-class pub. Ravelston is an ungrateful caricature of Richard Rees, the ‘socialist baronet’ and proprietor of The Adelphi. It was ‘Dickie’ who assisted Orwell into authorship, publishing the nucleus of articles that became his first book, Down and Out in Paris and London.

Comstock drags his rich best friend into the awful-smelling spit-and-sawdust boozer. What follows is usefully summarized via its ‘smell narrative’. ‘A sour cloud of beer seemed to hang about [the place]. The smell revolted Ravelston.’ They are served two pints of ‘dark common ale’ (‘mild’, for those who can remember the sickly-sweet-smelling swill). The air is ‘thick with gunpowdery tobacco-smoke’. Ravelston catches sight of a well-filled spittoon near the bar, averts his eyes and thinks, wistfully, of the wines of Burgundy.

The two friends have their usual argy-bargy about socialism. Ravelston tries, vainly, to explain Marx. What does Marx mean, Comstock snorts, in the stinking ‘spiritual sewer’ to which £2 a week has consigned him? ‘He began to talk in obscene detail of his life in Willowbed Road [his fifteen-bob-a-week lodgings]. He dilated on the smell of slops and cabbage, the clotted sauce-bottles in the dining-room, the vile food.’ ‘It’s bloody,’ murmurs Ravelston several times, in feeble sympathy. Bad-tempered, and with a belly full of bad beer, the two men go out into the now night-time street. The discussion drags on. If you’re poor, says Comstock, those who are not poor hate you – because you have a bad smell: ‘It’s like those ads for Listerine. “Why is he always alone? Halitosis is ruining his career.” Poverty is spiritual halitosis.’

Perverse, thinks Ravelston, with an automatic sniff. Desirable women won’t look at you, complains Gordon, now in full cry. You have to buy sex from women who smell as bad as you (there’s a later scene when, very drunk, Gordon does just that). Ravelston thinks, inwardly, of his fragrant mistress, Hermione, as wholesome to her lover’s nostrils as a ‘wheatfield in the sun’. ‘Don’t talk to me about the lower classes,’ she always says whenever he brings up his damned socialism. ‘I hate them. They SMELL.’ She must not call them the ‘lower classes’, he objects mildly (tacitly agreeing with the smell point). They are the ‘working class’. Very well, she says, ‘But they smell just the same.’

The two men go their separate ways: Comstock to his ‘slops and cabbage’ in Willowbed Road; Ravelston by taxi to his flat, where a sleepy Hermione is waiting for him, curled voluptuously, half-dressed, in an armchair. ‘We’ll go out and have supper at Modigliani’s,’ she commands (in other words, Quaglino’s in Piccadilly, London’s best restaurant). In the taxi she lies against him, still half asleep, her head pillowed on his breast. The ‘woman-scent’ breathes out of her. Philip inhales it, sensually, thinking of his favourite corner table at Modigliani’s and of sex, trying not to think of that vile pub with its hard benches, stale beer-stink and brass spittoons.

Outside Modigliani’s a beggar importunes them for money: ‘A cup of tea, guv’nor!’ The request is half-coughed through ‘carious teeth’. Halitosis. Spittle. Phlegm. SMELL. Hermione forbids Ravelston to give this human offal a single penny. Ravelston obeys. His socialism is a paper and print thing. He loves the people – but not their smell. He and Hermione dine, expensively, on grilled rump steak and half a bottle of Beaujolais. A feast to the nose and the palate.

Orwell’s feelings towards Rees and his kind were deeply confused. He was grateful enough for favours given to name his son (Richard Blair) after the socialist baronet who so helped his early career and whom he made his literary executor. He liked the man. Who could not? Everyone who knew him liked him. Yet Orwell hated Rees ‘for what he was’. Rees/Ravelston’s kind of socialism, well meant as it might be, smelled wrong to Orwell because it had the aroma of expensively scented sex, French cuisine and newly washed underwear, after the morning bath fragrant with its expensive Selfridges-bought ‘salts’. Where, then, was the healthy ‘smell’ of socialism to be found? Not in that ‘hotbed’ of theory, the LSE, dominated by the Laski faction – those incorrigible abusers of plain English (half-gramophone, half-megaphone, all phoney) and sympathizers with Moscow. Not in the brimming chamber pot under the working-class Wigan breakfast table. Not in what is called, in Aspidistra, the ‘money stink’ that leaks, like furtively broken wind, from the well-meaning, well-bred rich, like Ravelston.

It is found in two places, one deduces from Orwell’s writing. One is the naked coal miner, hundreds of feet underground, his finely muscled body exposed in the murky light: ‘but nearly all of them have the most noble bodies; wide shoulders tapering to slender supple waists, and small pronounced buttocks and sinewy thighs, with not an ounce of waste flesh anywhere.’ Around them the ‘fiery dusty smell’ of their work place. It is a ‘real’ smell. The stench of honest labour and erect manhood. The other location where socialism smells ‘right’ is the trenches of wartime Spain. ‘I suppose I have failed to convey more than a little of what those months in Spain meant to me,’ says Orwell in the epilogue to Homage to Catalonia: ‘I have recorded some of the outward events, but I cannot record the feeling they have left me with. It is all mixed up with sights, smells, and sounds that cannot be conveyed in writing.’ Orwell’s nose can do more than most, but it cannot put into words what it knows, on the senses, is right, and what is wrong.

And what, one wonders, would socialism smell of now, in the second decade of the twenty-first century, were Orwell and his diagnostic nose here to sniff it for us?

Nineteen Eighty-Four is at the top of teachers’ list of books ‘every student should read before leaving secondary school’.

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE TEACHING OF ENGLISH, July 2015

My acquaintance with Orwell occurred on 19 December 1954 – I can date it as precisely as my wedding days.

Nineteen Eighty-Four was published, by Orwell’s most loyal publisher, Frederic Warburg, on 9 June 1949. It sold brilliantly but by the autumn of 1954, three years after Orwell’s death, reprint sales had steadied to 150 a month; just sufficient to keep the novel in print. It was not, as now, a novel that the schoolteachers of England were advised to drill into their pupils like imams in a madrasa.

All this changed with Nigel Kneale’s ‘horror’ adaptation, put out by the BBC on Sunday evening, 12 December 1954. With it the novel’s rise to supersellerdom took off like a Guy Fawkes rocket from a milk bottle. The fact that it was the first novel in which the arch-villain is a television set must have helped. BB was watching Winston. When, then, would the BB(C) be watching us?

My family home couldn’t yet run to a ‘goggle-box’. I missed out on the first broadcast but, inflamed by playground gossip (‘rats! eyeballs!’), I was careful to book a place with a better-off friend to see the repeat, a week later. It wasn’t actually a repeat in the modern sense, there being no video technology then. The cast, troupers all, went through the whole thing again.

The production starred Peter Cushing as Winston Smith (the eighty-year-old Churchill, after whom he is named, was currently prime minister, which added a resonance). Cushing’s constipated, haunted look would be carried over into his portrayals of arch-agents of light versus darkness in Hammer Horror films of the 1960s. There was a preliminary Auntyish warning that the programme was ‘unsuitable for children or those with weak nerves’. This had the predictable effect of gluing even the most susceptible viewer (including, of course, fifteen-year-old schoolchildren like myself) to the screen, their nerves pinging like over-wound violin strings.

The dramatization (still available on YouTube, as a muzzy TV-grab from the surviving 35-mm film) opened with a clanging overture based on Holst’s ‘Mars’ and the monitory voiceover: ‘This is one man’s alarmed view of the future’ (not, that is, Lord Reith’s view). There followed a Wagnerian montage of atomic explosions before the opening scenes in Minitrue (an institution inspired, as we dimly apprehended, by the BBC’s Broadcasting House). And so, with the competent performance level of a good provincial repertory company, the narrative rolled on, for one hour and 47 minutes, to rats and eyeballs. Orwell’s bleak ending was respected by Kneale (as it was not in the CIA-financed animated film of Animal Farm that also came out in 1954; or the ciA-financed American version of Nineteen Eighty-Four).

The effect of the 1954 dramatization of Nineteen Eighty-Four on the population – soon, they were informed, to become telescreen-enslaved citizens of ‘Airstrip One: Oceania’ – was electrifying. Susceptible housewives, who had lived serenely through the Blitz, were reported (apocryphally) to have died of shock watching the ‘H[orror] Programme’. On 15 December five Conservative MPS put down a motion deploring ‘the tendency evident in recent BBC programmes, notably on Sunday evening, to pander to sexual and sadistic tastes’. A less pompously inclined weather forecaster began his bulletin with ‘Stand by your sets, Citizens, bad news coming up.’

Television lives by viewing figures. Those for Nineteen Eighty-Four were, for a live drama, unprecedented. The tally (seven million) was exceeded only by that for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth the previous year. ‘Big Brother is watching you’, ‘doublethink’, ‘thought-crime’ and the ‘two-minute hate’ became catchphrases. They still are.

The 1954 televization jump-started Orwell’s upward progress to his present status as the Cassandra of his time. All time, perhaps. As the estate’s literary agent, Bill Hamilton, reported in January 2015: ‘Interest in Orwell is accelerating and expanding practically daily . . . We’re selling in new languages – Breton, Friuli, Occitan – Total income has grown 10% a year for the last three years.’13 With some difficulty (it’s not yet on Google Translate) I’ve discovered that the Occitan for ‘Big Brother Is Watching You’ is ‘Gròs Hrair T’espia’.

Not only has Nineteen Eighty-Four lasted, selling nowadays better than ever; it is, we’re told, a work of biblical importance. In November 2014 a list was drawn up on behalf of YouGov (or ‘You the People Govern’, an interesting example of what Orwell calls ‘Newspeak’), asking a representative two thousand members of the reading public what they thought were ‘the most valuable books to humanity’. The top ten were as follows:

1) The Bible (37 per cent)

2) The Origin of Species (35 per cent)

3) A Brief History of Time (17 per cent)

4) Relativity: The Special and General Theory (15 per cent)

5) Nineteen Eighty-Four (14 per cent)

6) Principia Mathematica (12 per cent)

7) To Kill a Mockingbird (10 per cent)

8) The Qur’an (9 per cent)

9) The Wealth of Nations (7 per cent)

10) The Double Helix (6 per cent)

Nineteen Eighty-Four is judged more ‘valuable to humanity’ than the Qur’an. Not everyone (probably not two billion everyones in the Islamic world) would agree. But few would disagree with the assertion that Orwell ‘matters’. It is a pity he did not live to enjoy the vast revenue (the copyright is still in force for another five years) and join his rich friends on equal terms. What Orwell – who is recorded as giving away his meagre ration-book coupons to the deserving during the war – would have done with great wealth is a nice speculation.

I devoured Nineteen Eighty-Four in the days following the 1954 broadcast and had read all the principal works by the end of 1955.14 Any relationship such as mine with Orwell has been enriched by Penguin’s handsome, budget-price reprints (Allen Lane was a staunch admirer); by the four-volume The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell (Secker & Warburg, London, 1968), edited by Ian Angus and Sonia Orwell; and, climactically, by the twenty-volume Complete Works of George Orwell (1998). This last was the life’s work of Peter Davison. His efforts took seventeen years and required a sextuple bypass to complete, he told the launch party under UCL’s cupola, fifty yards from where Orwell had died. Few literary critics would pay the price that Davison did.

The posthumous biographical situation has been troubled. In the will made three days before his death, Orwell forbade biography. His widow, Sonia, whom he married on his deathbed, would be a ferocious guardian of the flame. It may be that Orwell had that prohibition in mind when he made her his ‘future widow’, as he bluntly put it. It may be, as Gordon Bowker shrewdly suggests, that she insisted on it, as a kind of prenup/post-mortem. In the years after her husband’s death, Sonia slammed the door in the face of any serious life-writer (as they are now called) by appointing the deeply unserious Malcolm Muggeridge, in 1955, as the ‘authorized biographer’ – with the implicit understanding that he would do nothing. He did nothing.

The first biographers to do something, Peter Stansky and William Abrahams, were forbidden by Sonia to quote any incopyright material and were denied access to literary remains. Friends and family were instructed not to cooperate. A ferocious anathema was published in the TLS when their book appeared. Sonia was convinced that they had somehow cheated her. But working as they did, shortly after Orwell’s death, the American biographers had access to living sources. Their work, hampered as it was, has been foundational in the personally vouched-for witness it supplies.

Nonetheless, Stansky and Abrahams were stumped, as all biographers have been, by strange turns in Orwell’s life. Why, having excelled at prep school, did he slack at Eton, closing off access to privileges that, with some effort, were his for the taking? Why did he, already sceptical about Empire, enrol and serve for five years in one of the most brutally exploited and neglected of the Crown’s colonial territories? And then, why did he come back, an Etonian, God help us, and plunge into the down-and-out depths of London and Paris?

Born into a class neurotic about sanitation, what was it about dirt that so fascinated and obsessed Orwell? He went to Spain, as many of the militant left did, but why volunteer for a Fred Karno’s Circus outfit like the POUM? Anarchists are damnably efficient terrorists but they do not make good soldiers of the line. What on earth does ‘Tory anarchism’, as Orwell called it, mean? Where, precisely, did Orwell’s ‘socialism’ lie? Was he, come to that, really a socialist? Did he love the working class (the ‘animals’ of Animal Farm) or did they, particularly their porcine (trade union) leaders, disgust him to the point of nausea? Did he ever tell the low-life characters he dossed and tramped with, and the miners he accompanied, that Mr Blair was writing about them, unflatteringly, under another name? Why, in the last year of his life, was he so desperately keen to marry? Why, on his deathbed, was he so insistently desperate that there should be no biography when so much of his writing was infused with autobiography?

Why did he, the creator of Big Brother, compose his ‘list’ – a lettre de cachet – denouncing people who thought they were his friends to one of the more sinister British secret-service agencies?15 One could extend the questions, but it is enough to say that his life is wreathed in enigma.

The problem is small – relative to what is unproblematically great in Orwell’s achievement. But it is troublesome. One could call it ‘VH’-the vein of hurtfulness in his fiction to those who did nothing to deserve cruelty.

Examples are legion. How could he, for example, write that cruel description of a son’s callous indifference at his father’s funeral in Coming Up for Air, as his own father was dying of cancer? (Luckily Richard Blair went to his burial having read only a glowing review of the novel.) His mother and sisters (particularly) had sacrificed their life chances for Eric’s expensive, and apparently wasted, start in life (as his father sacrificed a painfully large chunk of his income). It was not an easy thing for a family of four on £450 a year to send a child to Eton. Resourcefully, in 1933, Orwell’s mother and sister Avril set up a tea room and bridge club, ‘The Copper Kettle’, in Southwold’s Queen Street, where the family was then living. The café was a success and won them respectful affection from townspeople, along with good trade from summer holidaymakers. The Blairs’ Southwold tea room is scornfully rubbished in A Clergyman’s Daughter. In fact Avril did very well out of the Copper Kettle and her locally famed cakes. She even bought herself a new car with the profits. Orwell himself could not, for most of his life, afford motorized transport better than second-hand motorbikes. Avril had some right to be proud of her small achievement. What, then, did she and her mother (who ran the Copper Kettle bridge club) make of passages in A Clergyman’s Daughter like the following (Knype Hill is, transparently, Southwold):

The two pivots, or foci, about which the social life of the town moved were Knype Hill Conservative Club (fully licensed) . . . and Ye Olde Tea Shoppe, a little farther down the High Street, the principal rendezvous of the Knype Hill ladies. Not to be present at Ye Olde Tea Shoppe between ten and eleven every morning, to drink your ‘morning coffee’ and spend your halfhour or so in that agreeable twitter of upper-middle-class voices [it goes on lengthily in this vein].

The scorn shocks (‘Ye Olde Tea Shoppe’?) When he wrote this, Orwell, a thirty-year-old layabout, was out of work in his parents’ house, convalescing from pneumonia, at the very period the women were setting up their brave venture. He evidently disapproved.

When, after the publication of A Clergyman’s Daughter, he was on his uppers, his rich, aristocratic and ever-obliging friend Richard Rees helped find him a stop-gap job in a bookshop in Hampstead – then, as now, the most intellectually active enclave in Britain. The bookshop, a local institution at the corner of Pond Street and South End Road (there’s a Daunt’s nearby now) was called the ‘Booklovers’ Corner’. The branch of Le Pain Quotidien that has replaced it in this degenerate age has a plaque commemorating Orwell’s fifteen months’ service as an assistant and manager in the shop.16 The first fifty pages of Keep the Aspidistra Flying revolve around Gordon Comstock’s wage slavery in Booklovers’ Corner – unnamed in the novel. The proprietor in the novel is Mr McKechnie, a white-haired and white-bearded ‘dilapidated’ Scotsman (a nation Orwell peculiarly disliked). He is a chronically lazy, penny-pinching, stupid, rabidly teetotal, snuff-taking ignoramus who underpays and exploits Gordon before firing him for a night on the town that landed him in jail.

The actual proprietor of Booklovers’ Corner was Frank Westrope. A founder member of the Independent Labour Party (with which Orwell would affiliate himself a couple of years later), Westrope had been imprisoned for years as a conscientious objector during the First World War. His conduct was gallant. He was still, in the mid-1930s, under surveillance (as was Orwell when he worked in the shop) by M15. He was no teetotaller. He would certainly have been indulgent to, and amused by, a youngster as bright as Orwell (it was by this name that Eric Blair introduced himself to Westrope) who went on the razzle and found himself up in front of the beak next morning. Westrope’s wife, Myfanwy, had thrown herself into the suffrage movement. It would not, until 1928, fully emancipate women.17 The kindest of landladies, she gave Orwell a bedsit around the corner, rent-free for six months, and intimated that she would turn a blind eye if he invited girlfriends in (this was freethinking Hampstead). He did. Noisily, according to later complaints (he was running at least two women – ‘compartmentalized’, as one of them later complained – during his months at the shop).

In the novel, Gordon pigs it in wretched lodgings: his ogre of a landlady’s ears are always suspiciously cocked to hear any creaking bed springs in the rooms of her ‘paying guests’. Then it’s ‘pack your bags and get out, you filthy fellow’.

Booklovers’ Corner also had a ‘tuppenny library’ of current bestsellers. Good-Bad Books, as Orwell called the best of them. These, however, were not, all of them, the best bad books. They were tat of the Ethel M. Dell and Edgar Wallace kind. Before Allen Lane’s Penguins came on the scene in 1936, ‘tuppenny’ loans were a profitable sideline. Even Boots the Chemist lent them. Orwell is scathing in Keep the Aspidistra Flying about the clientele who patronize the 800 volumes of ‘soggy, half-baked trash’ Gordon is in charge of. Dowdy, ill-smelling women, so-called ‘book lovers’, come in, looking like ‘draggled ducks nosing among garbage’, with their insatiable appetite for Ethel M. Dell’s romantic slush and the loathed Warwick Deeping (author of Sorrell and Son, 1925). Similarly held up for scorn are timid smut hunters (how Lawrence’s Women in Love will disappoint them!) and ‘nancies’, delicately fondling books about ballet. There is not a single admirable customer in the hateful bookshop Gordon superintends, and no ‘Hampstead Intellectuals’.

Booklovers’ Corner: Gordon Comstock’s hell.

Victor Gollancz, the publisher of Keep the Aspidistra Flying – soon to launch, in 1936, his Left Book Club (in which Orwell would later publish The Road to Wigan Pier) – had a high regard for his fellow socialist Frank Westrope and for Hampstead intellectuals generally. When Gollancz pointed out to Orwell that the depiction of Frank (and, indirectly, his wife) was derogatory and possibly libellous, the author replied, in honest innocence, how could that be? Mr McKechnie is Scottish, has a white beard and takes snuff. Frank Westrope was clean-shaven, English and did not take snuff. Case closed. No malicious intent whatsoever. Orwell, so clear-headed about so many things, never seems to have worked out what libel and its consequent criminal damage were. If there was one place in London where a book like Keep the Aspidistra Flying was likely to be read (did Westrope display it in the window?), it was bookish Hampstead. What customers, thereafter, would be encouraged to browse and buy from the Westrope establishment with the imputation hanging over them that they were so many draggled ducks, smut hounds and nancy boys? And knowing that the superior young man behind the desk was looking at them with secret contempt, which he would put into print?

Why did Orwell hurt in this way (as he surely did) the Westropes, who had offered him nothing but kindness? What had the kindly Richard Rees, who got him the Booklovers’ Corner job (a life saver), done to deserve the lampoon of himself as Ravelston in Keep the Aspidistra Flying? Or the literary critic William Empson in Nineteen Eighty-Four as the big-brained buffoon Ampleforth? To find yourself in Orwell’s novels, said the woman he first loved, was to feel torn limb from limb.

You might find it interesting to be a writer’s widow.

ORWELL’s proposal to his second wife, Sonia

Orwell’s depiction of his first wife, Eileen (as Rosemary), in Keep the Aspidistra Flying is disparaging.18 Much more so is the fictional portrait of his second wife. It is accepted that Julia in Nineteen Eighty-Four ‘is’ Sonia. Hilary Spurling titles the memoir of her friend The Girl from the Fiction Department. It’s how Winston Smith first identifies his future lover.19

In Nineteen Eighty-Four Julia works in Pornosec (the ‘Muck Factory’), engaged in churning out ‘the lowest kind of pornography’. Sonia Brownell (later ‘Orwell’ – she took his pen name in marriage rather than ‘Blair’) was, in fact, a long-serving co-editor, with Stephen Spender and Cyril Connolly, of the most distinguished literary magazine of the 1940s and early 1950s, Horizon.20 It was no muck factory. Among the galaxy of writers it published was George Orwell. Sonia later worked as an editor at Weidenfeld & Nicolson, where she is credited with ‘discovering’ the novelist Angus Wilson. She had sound literary, and even better artistic, taste. Anthony Powell depicts her, admiringly and infinitely more kindly than does Orwell in Nineteen Eighty-Four, as the efficient Ada Leintwardine in Books Do Furnish a Room.

For her lovers, Sonia Brownell was not merely a beauty (‘the Venus of Euston Road’ – she was sketched by an admiring Picasso and Lucian Freud) and a gratifyingly easy lay (allegedly Connelly would pimp her out to potential backers of his magazine), but an intellectual equal. The love of her life was not Orwell, but the philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty. She formed lifelong friendships with such other French intellectuals (her command of French was perfect) as Georges Bataille, Jacques Lacan (later the darling of deconstruction) and the roman nouveau novelist Marguerite Duras, whose work Sonia translated and who honoured her with yet another friendly depiction in her fiction.

Sonia Orwell (left), the Venus ofEuston Road, at work in the Horizon office.

In Nineteen Eighty-Four, Julia is depicted as an intellectual dolt. She falls asleep when Winston Smith reads The Theory of Oligarchical Collectivism out loud to her. It is beyond her feeble brain. Sonia Brownell, by contrast, had no difficulty, we understand, grappling with Merleau-Ponty’s Phénoménologie de la perception, or Bataille’s Histoire de l’oeil. Julia’s one virtue in Nineteen Eighty-Four is that she has a politically rebellious vagina, which she uses like an anarchist’s indiscriminate bomb. Winston raves about the organ’s voracity. ‘Listen,’ says Winston, ‘The more men you’ve had, the more I love you. Do you understand that?’ Was Sonia’s highest claim to Orwell’s respect that she had been, over the course of her life, rampantly promiscuous? A living vagina dentata? Sonia had not liked Orwell, when healthy, as a lover. She was one of the ‘once in a lifetime with that man is quite enough’ party. She was not, the evidence suggests, the ‘gold-digger’ some biographers have portrayed her as. She would have been the least competent gold-digger in literary history. She died so penniless that her friends Francis Bacon and Hilary Spurling had to kick in for her funeral. The reason she married Orwell, I suspect, was that she respected what he was – a great writer. And serving the writing and art she most admired was her self-imposed mission in life. Stephen Spender liked to tell a story about Sonia that is probably apocryphal but which contains an essential truth about the woman. She was spending a weekend

in the country with Connolly’s friend Dick Wyndham, a leathery, lustful satyr who pursued her round his garden until she dashed into the pond. ‘It wasn’t his trying to rape me that I mind,’ she gasped when the writer Peter Quennell fished her out, ‘but that he doesn’t seem to realize what Cyril stands for.’

She married Orwell because of what he stood for. Literary greatness.

Particularly hurtful in Orwell’s depiction of Julia was O’Brien’s casual answer to Winston’s question, ‘What have you done with Julia?’ O’Brien smiles: ‘She betrayed you, Winston. Immediately – unreservedly.’ Sonia never betrayed the man whose name she bore.

Why, one wistfully thinks, could Orwell not have portrayed a more loyal and clever Julia/Sonia in his last novel? It would not have hurt, in either sense – hurt the novel, or hurt her.

Finally, in 1974, Sonia relented and broke the dying Orwell’s prohibition. The pressure had become irresistible. She invited Bernard Crick to write an ‘authorized’ biography. Crick was the editor of Political Quarterly and an LSE-trained political scientist with no outstanding literary-critical qualifications. He was mystified at the summons. Sonia was reportedly won over by a review in which he had called Orwell a ‘giant with warts’ and by his unrelenting attacks on the then prime minister, Harold Wilson.

Crick took as his guiding thesis the premise that Orwell’s great, and achieved, mission had been to turn political writing into art. The subtext, for hard-nosed Crick, was that Orwell’s fine words buttered no political parsnips. Himself a no-nonsense writer, Crick had no pretension to any art whatsoever. He was sadly lacking a ‘literary touch’, sighed Frank Kermode, reviewing the resulting biography.21 True enough. What political scientist trusts ‘literature’? Crick, it was clear, saw Orwell as a political ignoramus.

Sonia did not like one bit this line of biography that she had unwittingly commissioned. Crick was determined that his portrait would be ‘external’. There would be no psycho-biographical nonsense. And he would be Solomonic in his judgements. He acid-tests for falseness such ubiquitously quoted (late-life) declarations as: ‘From a very early age, perhaps the age of five or six, I knew that when I grew up I should be a writer.’22 In their milestone four-volume Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell Sonia and her co-editor, Ian Angus, use that sentence as their epigraph. This was the dominant Orwellian ‘fact’. It was as if a fairy godmother had come to little Eric Blair’s cradle, waved a wand and uttered ‘Be a writer, my child.’ But does it, Crick wondered, if you give it a moment’s thought (and recollect your own career aspirations aged five), ring true? A train driver, perhaps. But a ‘writer’? By his own account, little Eric was only months past bedwetting. Orwell was, Crick concluded mildly, ‘laying it on a bit thick’. He peeled off many other layers of thickness. Leaving what? Not enough to keep admirers of Orwell happy.

Least of all the woman who had ‘authorized’ Crick. There was much in his account to vex Sonia – and not merely his antipathy to literariness and refusal to take anything Orwell wrote at face value. He chronicled, without moral judgement, Orwell’s apparent indifferent attention to his first wife, as she died on the operating table of something he never seemingly inquired about (uterine cancer). And, along the way, there was his wayward, sometimes ‘rough’, sexuality, of which telling glimpses were on record. Crick glimpsed and recorded, with a cold, camera-like eye. And, unflatteringly to his patroness, he recorded the string of women to whom Orwell impulsively proposed when he knew for a fact that he was dying. Sonia came in at about number five.

Crick’s authorized biography saw publication, belatedly, in 1980. A mortified Sonia’s last weeks, petulant, alcoholic and broke, were anything but sweetened by the account she had brought into being. Crick’s task had been complicated, at every step, by his fallings-out with Sonia. Her touchiness is immortalized by her vitriolic, much-quoted outburst across a dinner table when Crick queried one of the most frequently cited ‘facts’ about Orwell and Empire: ‘Of course he shot the fucking elephant. He said he did. Why do you always doubt his word!’ Crick, predictably, is highly sceptical about the elephanticide, although he valued the famous essay as a brilliant allegory of the rotten core of colonial power.

Orwell inspires moral nobility in his admirers. Crick, not a rich man, made over his royalties to found the Orwell Society and its annual prize.

Orwell in his NUJ picture, 1930s.

Other, less self-restricting, full-life biographies followed. They went, some of them, very psycho-biographical. Gordon Bowker, the most intrepid, promised that ‘the main thrust of [my] book will be to reach down as far as possible to the roots of [Orwell’s] emotional life, to get as close as possible to the dark sources mirrored in his work.’ But all the biographers have been obliged, in the main, to chew over the same old facts, from their subject’s first recorded word (‘beastly’) to the fact that his coffin was six inches too long for his grave. He was always an awkward customer.

Orwell remained shadowy. Maddeningly, for someone who had worked at the BBC, there were no voice or pictorial recordings (he had a ‘flat’, toneless voice, we are told, croakier after he was shot in the throat in Spain), no moving film and very few photographs of the man. No revealing private journals. Reviewers of Davison’s mountainous Collected Works concluded that their sense of Orwell had been usefully solidified, but not overset. And the enigmas remained. Still remain. It was almost as if, like Winston Smith, he had a memory hole beside his desk. Stansky and Abrahams had called their quick-off-the-mark biography The Unknown Orwell (1972). They, and their successors, could have called it ‘the unknowable Orwell’.

The most informative of the post-Crick biographies are currently the third generation (following the work of the Americans Stansky and Abrahams, Michael Shelden and Jeffrey Meyers) by D. J. Taylor and Gordon Bowker, both published in 2003. As a novelist, Taylor lets his imagination loose more than the others. Among Orwell’s scrawled final words in his hospital notebook are: ‘At 50, every man has the face he deserves.’ He never made that age, but what does that rueful, moustached, expressionless face in the few photographs that survived tell us? Taylor was imaginatively speculative about that. He presents, I think, the ‘living’ Orwell as well as anyone will ever be able to. Paul Foot, in a haughty review of Taylor’s biography (it annoyed him as being insufficiently engaged politically), was rude. What next, he asked, a biographical meditation on ‘Orwell’s bum’?23 Actually, that might be interesting, if lifelong scars remained on the traumatically caned buttocks. They might explain a lot about the punitive and self-punitive Orwell.

For me, Taylor’s and Bowker’s are the biographies to start from, as on their part they started from Crick. Their accounts have been added to, and complicated, by new tranches of correspondence that have more recently come to light. John Rodden has been illuminating.24 Critical verdicts are in on all the half-dozen or so biographies: mine are supererogatory other than that I have drawn on them gratefully.

What I offer here is an approach from oblique, self-indulgent angles. The relationship of coarse fishing (that smelliest of sports) to Orwell’s notion of civilization, for example, may be thought a little too fine-drawn. But the indirect approach can sometimes pay off, as in John Ross’s illuminatingly medical Orwell’s Cough (2012). George Orwell’s bum may, I concede, be an obliquity too far.