The chapter contains the proof of the Chow’s Theorem, a fundamental result for algebraic varieties with an important consequence for the study of statistical models. It states that, over an algebraically closed field, like  , the image of a projective (or multiprojective) variety X under a projective map is a Zariski closed subset of the target space, i.e., it is itself a projective variety.

, the image of a projective (or multiprojective) variety X under a projective map is a Zariski closed subset of the target space, i.e., it is itself a projective variety.

The proof of Chow’s Theorem requires an analysis of projective maps, which can be reduced to a composition of linear maps, Segre maps and Veronese maps.

The proof also will require the introduction of a basic concept of the elimination theory, i.e., the resultant of two polynomials.

10.1 Linear Maps and Change of Coordinates

We start by analyzing projective maps induced by linear maps of vector spaces.

The nontrivial case concerns linear maps which are surjective but not injective. After a change of coordinates, such maps induce maps between projective varieties that can be described as projections .

Despite the fact that the words projective and projection have a common origin (in the paintings of the Italian Renaissance, e.g.) projections not always give rise to projective maps.

The description of the image of a projective variety under projections relies indeed on nontrivial algebraic tools: the rudiments of the elimination theory.

Let us start with a generalization of Example 9.3.3.

Definition 10.1.1

Consider a linear map  which is injective.

which is injective.

Then  defines a projective map (which, by abuse, we will still denote by

defines a projective map (which, by abuse, we will still denote by  ) between the projective spaces

) between the projective spaces  , as follows:

, as follows:

– for all  , consider a set of homogeneous coordinates

, consider a set of homogeneous coordinates ![$$[x_0 : \dots : x_n]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq8.png) and send P to the point

and send P to the point  with homogeneous coordinates

with homogeneous coordinates ![$$[\phi (x_0,\dots ,x_n)]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq10.png) .

.

Such maps are called linear projective maps .

It is clear that the point  does not depend on the choice of a set of coordinates for P, since

does not depend on the choice of a set of coordinates for P, since  is linear.

is linear.

Notice that we cannot define a projective map in the same way when  is not injective. Indeed, in this case, the image of a point P whose coordinates lie in the Kernel of

is not injective. Indeed, in this case, the image of a point P whose coordinates lie in the Kernel of  would be indeterminate.

would be indeterminate.

Since any linear map  is defined by linear homogeneous polynomials, then it is clear that the induced map between projective spaces is indeed a projective map.

is defined by linear homogeneous polynomials, then it is clear that the induced map between projective spaces is indeed a projective map.

Example 10.1.2

Assume that the linear map  is an isomorphism of

is an isomorphism of  . Then the corresponding linear projective map is called a change of coordinates

.

. Then the corresponding linear projective map is called a change of coordinates

.

Indeed  corresponds to a change of basis inside

corresponds to a change of basis inside  .

.

The associated map  is an isomorphism, since the inverse isomorphism

is an isomorphism, since the inverse isomorphism  determines a projective map which is the inverse of

determines a projective map which is the inverse of  .

.

Remark 10.1.3

By construction, any change of coordinates in a projective space is a homeomorphism of the corresponding topological space, in the Zariski topology.

So, the image of a projective variety under a change of coordinates is still a projective variety.

From now on, when dealing with projective varieties, we will freely act with the change of coordinates on them.

The previous remark generalizes to any linear projective map.

Proposition 10.1.4

For every injective map  ,

,  , the associated linear projective map

, the associated linear projective map  sends projective subvarieties of

sends projective subvarieties of  to projective subvarieties of

to projective subvarieties of  .

.

In topological terms, any linear projective map is closed in the Zariski topology, i.e., it sends closed sets to closed sets.

Proof

The linear map  factorizes in a composition

factorizes in a composition  where

where  is the inclusion which sends

is the inclusion which sends ![$$[x_0:\dots :x_n]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq31.png) to

to ![$$[x_0:\dots :x_n:0:\dots :0]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq32.png) ,

,  zeroes, and

zeroes, and  is a change of coordinates (notice that we are identifying the coordinates in

is a change of coordinates (notice that we are identifying the coordinates in  with the first

with the first  coordinates in

coordinates in  ).

).

Thus, up to a change of coordinates, any linear projective map can be reduced to the map that embeds  into

into  as the linear space defined by equations

as the linear space defined by equations  .

.

It follows that if  is the subvariety defined by homogeneous polynomials

is the subvariety defined by homogeneous polynomials  then, up to a change of coordinates, the image of X is the projective subvariety defined in

then, up to a change of coordinates, the image of X is the projective subvariety defined in  by the polynomials

by the polynomials  .

.

The definition of linear projective maps, which requires that  is injective, becomes much more complicated if we drop the injectivity assumption.

is injective, becomes much more complicated if we drop the injectivity assumption.

Let  be a non injective linear map. In this case, we cannot define through

be a non injective linear map. In this case, we cannot define through  a projective map

a projective map  as above, since for any vector

as above, since for any vector  in the kernel of

in the kernel of  , the image of the point

, the image of the point ![$$[p_0:\dots :p_n]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq52.png) is undefined, because

is undefined, because  vanishes.

vanishes.

On the other hand, the kernel of  defines a projective linear subspace of

defines a projective linear subspace of  , the projective kernel

, which will be denoted by

, the projective kernel

, which will be denoted by  .

.

If  is a subvariety which does not meet

is a subvariety which does not meet  , then the restriction of

, then the restriction of  to the coordinates of the points of X determines a well-defined map from X to

to the coordinates of the points of X determines a well-defined map from X to  .

.

Example 10.1.5

Consider the point  of projective coordinates

of projective coordinates ![$$[1:0:0:\dots :0]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq62.png) and let M be the linear subspace of

and let M be the linear subspace of  of the points with first coordinate equal to 0, i.e.,

of the points with first coordinate equal to 0, i.e.,  . Let

. Let  be the linear surjective (but not injective) map which sends a vector

be the linear surjective (but not injective) map which sends a vector  to

to  .

.

Notice that M defines a linear projective subspace  , of projective dimension

, of projective dimension  (i.e., a hyperplane), and

(i.e., a hyperplane), and  . Moreover

. Moreover  is exactly the projective kernel of

is exactly the projective kernel of  . Let Q be any point of

. Let Q be any point of  different from

different from  . If

. If ![$$Q=[q_0: q_1 :\cdots : q_m]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq75.png) then

then  determines a well defined projective point, which corresponds to the intersection of

determines a well defined projective point, which corresponds to the intersection of  with the line

with the line  . This is the reason why we call

. This is the reason why we call  the projection from

the projection from  to

to  . Notice that we cannot define a global projection

. Notice that we cannot define a global projection  , since it would not be defined in

, since it would not be defined in  . What we get is a set-theoretic map

. What we get is a set-theoretic map  . For any other choice of a point

. For any other choice of a point  and a hyperplane H, not containing P, there exists a change of coordinates which sends P to

and a hyperplane H, not containing P, there exists a change of coordinates which sends P to  and H to

and H to  . Thus the geometric projection

. Thus the geometric projection  from P to H is equal to the map described above, up to a change of coordinates.

from P to H is equal to the map described above, up to a change of coordinates.

We can generalize the construction to projections from positive dimensional linear subspaces.

Namely, for a fixed  consider the subspace

consider the subspace  , of dimension

, of dimension  , formed by the

, formed by the  -tuples of type

-tuples of type  and let M be the

and let M be the  -dimensional linear subspace of

-dimensional linear subspace of  -tuples of type

-tuples of type  . Let

. Let  be the linear surjective (but not injective) map which sends any

be the linear surjective (but not injective) map which sends any  to

to  .

.

Notice that N and M define disjoint linear projective subspaces, respectively  , of projective dimension

, of projective dimension  , and

, and  , of projective dimension n. Let Q be a point of

, of projective dimension n. Let Q be a point of  (this means exactly that Q has coordinates

(this means exactly that Q has coordinates ![$$[q_0:\dots :q_n]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq104.png) , with

, with  for some index i between 0 and n). Then the image of Q under

for some index i between 0 and n). Then the image of Q under  is a well defined projective point, which corresponds to the intersection of

is a well defined projective point, which corresponds to the intersection of  with the projective linear subspace spanned by

with the projective linear subspace spanned by  and Q. This is why we get from

and Q. This is why we get from  a set-theoretic map

a set-theoretic map  , which we call the projection from

, which we call the projection from  to

to  .

.

For any choice of two disjoint linear subspaces  , of dimension

, of dimension  , and

, and  , of dimension n,there exists a change of coordinates which sends

, of dimension n,there exists a change of coordinates which sends  to

to  and

and  to

to  . Thus the geometric projection

. Thus the geometric projection  from

from  to

to  is equal to the map described above, up to a change of coordinates.

is equal to the map described above, up to a change of coordinates.

Example 10.1.6

Let  be any surjective map, with kernel

be any surjective map, with kernel  (of dimension

(of dimension  ). We can always assume, up to a change of coordinates, that

). We can always assume, up to a change of coordinates, that  coincides with the subspace N defined in Example 10.1.5. Then considering the linear subspace

coincides with the subspace N defined in Example 10.1.5. Then considering the linear subspace  defined in Example 10.1.5, we can find an isomorphism of vector spaces

defined in Example 10.1.5, we can find an isomorphism of vector spaces  from M to

from M to  such that

such that  , where

, where  is the map introduced in Example 10.1.5. Thus, after an isomorphism and a change of coordinates,

is the map introduced in Example 10.1.5. Thus, after an isomorphism and a change of coordinates,  acts on points of

acts on points of  as a geometric projection.

as a geometric projection.

Example 10.1.6 suggests the following definition.

Definition 10.1.7

Given a linear surjective map  and a subvariety

and a subvariety  which does not meet

which does not meet  , the restriction map

, the restriction map  is a well defined projective map, which will be denoted as a projection of X from

is a well defined projective map, which will be denoted as a projection of X from  . The subspace

. The subspace  is also called the center of the projection.

is also called the center of the projection.

Notice that  is a projective map, since it is defined, up to isomorphisms and change of coordinates, by (simple) homogeneous polynomials (see Exercise 31).

is a projective map, since it is defined, up to isomorphisms and change of coordinates, by (simple) homogeneous polynomials (see Exercise 31).

Thus, linear surjective maps define projections from suitable subvarieties of  to

to  . Next section is devoted to prove that projections are closed, in the Zariski topology.

. Next section is devoted to prove that projections are closed, in the Zariski topology.

10.2 Elimination Theory

In this section, we introduce the basic concept of the elimination theory: the resultant of two polynomials.

The resultant provides an answer to the following problem:

– assume we are given two (not necessarily homogeneous) polynomials ![$$f,g\in \mathbb C[x]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq143.png) . Clearly both f and g factorize in a product of linear factors. Which algebraic condition must f, g satisfy to share a common factor, hence a common root?

. Clearly both f and g factorize in a product of linear factors. Which algebraic condition must f, g satisfy to share a common factor, hence a common root?

Definition 10.2.1

. Write

. Write  and

and  . The resultant

R(f, g) of f, g is the determinant of the Sylvester matrix

S(f, g), which in turn is the

. The resultant

R(f, g) of f, g is the determinant of the Sylvester matrix

S(f, g), which in turn is the  matrix defined as follows:

matrix defined as follows:

Notice that when f is constant and g has degree  , then by definition

, then by definition  .

.

Example 10.2.2

and

and  (both vanishing at

(both vanishing at  ), the resultant R(f, g) is

), the resultant R(f, g) is

Proposition 10.2.3

With the previous notation, f and g have a common root if and only if  .

.

Proof

The proof is immediate when either f or g are constant (Exercise 33).

![$$\mathbb C[x]_i$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq154.png) for the vector space of polynomials of degree

for the vector space of polynomials of degree  in

in ![$$\mathbb C[x]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq156.png) . Then the transpose of S(f, g) is the matrix of the linear map:

. Then the transpose of S(f, g) is the matrix of the linear map:![$$ \phi : \mathbb C[x]_{m-1}\times \mathbb C[x]_{n-1}\rightarrow \mathbb C[x]_{m+n-1} $$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_Equ4.png)

(matrix computed with respect to the natural basis defined by the monomials). Thus

(matrix computed with respect to the natural basis defined by the monomials). Thus  if and only if the map has a nontrivial kernel.

if and only if the map has a nontrivial kernel.Let  be a nontrivial element of the kernel, i.e.,

be a nontrivial element of the kernel, i.e.,  . Consider the factors

. Consider the factors  of f, where the

of f, where the  ’s are the roots of f (possibly some factor is repeated). Then, all these factors must divide

’s are the roots of f (possibly some factor is repeated). Then, all these factors must divide  . Since

. Since  , at least one factor

, at least one factor  must divide g. Thus

must divide g. Thus  is a common root of f and g.

is a common root of f and g.

Conversely, if  is a common root of f and g, then

is a common root of f and g, then  divides both f and g. Hence setting

divides both f and g. Hence setting  ,

,  , one finds a nontrivial element

, one finds a nontrivial element  of the kernel of

of the kernel of  , so that

, so that  .

.

We have the analogue construction if f, g are homogeneous polynomials in two or more variables.

Definition 10.2.4

If f, g are homogeneous polynomials in ![$$\mathbb C[x_0,x_1, \dots , x_r]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq175.png) one can define the 0th resultant

one can define the 0th resultant  of f, g just by considering f and g as polynomials in

of f, g just by considering f and g as polynomials in  , with coefficients in

, with coefficients in ![$$\mathbb C[x_1,\dots ,x_r]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq178.png) , and taking the determinant of the corresponding Sylvester matrix

, and taking the determinant of the corresponding Sylvester matrix  .

.

is thus a polynomial in

is thus a polynomial in  .

.

and

and  , then the 0th resultant is:

, then the 0th resultant is:

Proposition 10.2.5

![$$\mathbb C[x_0,x_1, \dots , x_r]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq184.png) . Then

. Then  vanishes at

vanishes at  if and only if there exists

if and only if there exists  with:

with:

Less obvious, but useful, is the following remark on the resultant of two homogeneous polynomials.

Proposition 10.2.6

Let f, g be homogeneous polynomials in ![$$\mathbb C[x_0,x_1, \dots , x_r]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq188.png) . Then

. Then  is homogeneous.

is homogeneous.

Proof

of the Sylvester matrix

of the Sylvester matrix  are homogeneous and their degrees decrease by 1 passing from one element

are homogeneous and their degrees decrease by 1 passing from one element  to the next element

to the next element  in the same row (unless some of them is 0). Thus for any nonzero entry

in the same row (unless some of them is 0). Thus for any nonzero entry  of the matrix, the number

of the matrix, the number  depends only on the row i. Call it

depends only on the row i. Call it  . Then the summands given by any permutation, in the computation of the determinant, are homogeneous of same degree:

. Then the summands given by any permutation, in the computation of the determinant, are homogeneous of same degree:

is homogeneous, and its degree is equal to d.

is homogeneous, and its degree is equal to d.

Next, a fundamental property of the resultant  is that it belongs to the ideal generated by f and g. We will not give a full proof of this property, and refer to the book [1] for it.

is that it belongs to the ideal generated by f and g. We will not give a full proof of this property, and refer to the book [1] for it.

Instead, we just prove that  belongs to the radical of the ideal generated by f and g, which is sufficient for our aims.

belongs to the radical of the ideal generated by f and g, which is sufficient for our aims.

Proposition 10.2.7

Let f, g be homogeneous polynomials in ![$$\mathbb C[x_0,x_1, \dots , x_r]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq201.png) . Then

. Then  belongs to the radical of the ideal generated by f and g.

belongs to the radical of the ideal generated by f and g.

Proof

vanishes at all points of the variety defined by f and g. But this is obvious from Proposition 10.2.5: if

vanishes at all points of the variety defined by f and g. But this is obvious from Proposition 10.2.5: if ![$$[\alpha _0:\alpha _1:\dots :\alpha _r]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq204.png) are homogeneous coordinates of

are homogeneous coordinates of  , then

, then

and

and  , polynomials in

, polynomials in ![$$\mathbb C[x_0]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq208.png) , have a common root

, have a common root  .

.

10.3 Forgetting a Variable

In Sect. 10.1 we introduced the projection maps as projectifications of surjective linear maps  . It is important to recall that when

. It is important to recall that when  has nontrivial kernel (i.e., when

has nontrivial kernel (i.e., when  ) the projection is not defined as a map between the two projective spaces

) the projection is not defined as a map between the two projective spaces  and

and  . On the other hand, for any subvariety

. On the other hand, for any subvariety  which does not intersect the projectification of

which does not intersect the projectification of  , the map

, the map  corresponds to a well defined projective map

corresponds to a well defined projective map  .

.

In this section, we describe the image of a variety in a projection  from a point, i.e., when the center of projections has dimension 0. It turns out, in particular, that

from a point, i.e., when the center of projections has dimension 0. It turns out, in particular, that  is itself an algebraic variety.

is itself an algebraic variety.

Through this section, consider the surjective linear map  which sends

which sends  to

to  . The kernel of the map is generated by

. The kernel of the map is generated by  . Thus, if X is a projective variety in

. Thus, if X is a projective variety in  which misses the point

which misses the point ![$$P_0=[1:0:\dots :0]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq227.png) , then the map induces a well defined projective map

, then the map induces a well defined projective map  : the projection from

: the projection from  (see Definition 10.1.7).

(see Definition 10.1.7).

For any point  ,

, ![$$Q=[q_1:\dots :q_n]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq231.png) , the inverse image of Q in X is the the intersection of X with the line joining

, the inverse image of Q in X is the the intersection of X with the line joining  and Q. Thus

and Q. Thus  is the set of points in X with coordinates

is the set of points in X with coordinates ![$$[q_0:q_1:\dots :q_n]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq234.png) , for some

, for some  .

.

Remark 10.3.1

For all  , the inverse image

, the inverse image  is finite.

is finite.

Indeed  is a Zariski closed set in the line

is a Zariski closed set in the line  , and it does not contain

, and it does not contain  , since

, since  . The claim follows since the Zariski topology on a line is the cofinite topology.

. The claim follows since the Zariski topology on a line is the cofinite topology.

![$$J\subset \mathbb C[x_0,\dots ,x_n]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq242.png) be the homogeneous ideal associated to X. Define:

be the homogeneous ideal associated to X. Define:![$$ J_0=J\cap \mathbb C[x_1,\dots ,x_n]. $$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_Equ9.png)

is the set of elements in J which are constant with respect to the variable

is the set of elements in J which are constant with respect to the variable  . In Chap. 13 we will talk again about Elimination Theory, but from the point of view of Groebner Basis; there, the ideal

. In Chap. 13 we will talk again about Elimination Theory, but from the point of view of Groebner Basis; there, the ideal  will be called the first elimination ideal

of J (Definition 13.5.1).

will be called the first elimination ideal

of J (Definition 13.5.1).Remark 10.3.2

is a homogeneous radical ideal in

is a homogeneous radical ideal in ![$$\mathbb C[x_1,\dots ,x_n]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq247.png) .

.

Indeed  is obviously an ideal. Moreover for any

is obviously an ideal. Moreover for any  , any homogeneous component

, any homogeneous component  of g belongs to J, because J is homogeneous, and does not contain

of g belongs to J, because J is homogeneous, and does not contain  . Thus

. Thus  , and this is sufficient to conclude that

, and this is sufficient to conclude that  is homogeneous (see Proposition 9.1.15).

is homogeneous (see Proposition 9.1.15).

If  for some

for some ![$$g\in \mathbb C[x_1,\dots ,x_n]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq255.png) , then

, then  , because J is radical, moreover g does not contain

, because J is radical, moreover g does not contain  . Thus also

. Thus also  .

.

We prove that  is the projective variety defined by

is the projective variety defined by  . We will need the following refinement of Lemma 9.1.5:

. We will need the following refinement of Lemma 9.1.5:

Lemma 10.3.3

Let  be a finite set of points in

be a finite set of points in  . Then there exists a linear form

. Then there exists a linear form ![$$\ell \in \mathbb C[x_0,\dots ,x_n]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq263.png) such that

such that  for all i.

for all i.

If none of the  ’s belong to the variety defined by a homogeneous ideal J, then there exists

’s belong to the variety defined by a homogeneous ideal J, then there exists  such that

such that  for all i.

for all i.

Proof

Fix a set of homogeneous generators  of J.

of J.

First assume that all the  ’s are linear. Then the

’s are linear. Then the  ’s define a subspace L of the space of linear homogeneous polynomials in

’s define a subspace L of the space of linear homogeneous polynomials in ![$$\mathbb C[x_0,\dots ,x_n]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq271.png) . For each

. For each  , the set

, the set  of linear forms in L that vanish at

of linear forms in L that vanish at  is a linear subspace of L, which is properly contained in L, because some

is a linear subspace of L, which is properly contained in L, because some  does not vanish at

does not vanish at  . Since a nontrivial complex linear space cannot be the union of a finite number of proper subspaces, we get that for a general choice of

. Since a nontrivial complex linear space cannot be the union of a finite number of proper subspaces, we get that for a general choice of  , the linear form

, the linear form  does not belong to any

does not belong to any  , thus

, thus  for all i. This proves the second claim for ideals generated by linear forms.

for all i. This proves the second claim for ideals generated by linear forms.

The first claim now follows soon, since the (irrelevant) ideal J generated by all the linear forms defines the empty set.

For general  , call

, call  the degree of

the degree of  and

and  If

If  is a linear form that does not vanish at any

is a linear form that does not vanish at any  , then

, then  is a form of degree d that vanishes at

is a form of degree d that vanishes at  precisely when

precisely when  vanishes. The forms

vanishes. The forms  define a subspace

define a subspace  of the space of forms of degree d. For all i, the set of forms in

of the space of forms of degree d. For all i, the set of forms in  that vanish at

that vanish at  is a proper subspace of

is a proper subspace of  . Thus, as before, for a general choice of

. Thus, as before, for a general choice of  , the form

, the form  is an element of J which does not vanish at any

is an element of J which does not vanish at any  .

.

Theorem 10.3.4

The variety defined in  by the ideal

by the ideal  coincides with

coincides with  .

.

Proof

,

, ![$$Q=[q_1:\dots :q_n]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq303.png) . Then there exists

. Then there exists  such that the point

such that the point ![$$P=\pi ^{-1}(Q)=[q_0:q_1:\dots :q_n]\in \mathbb P^n$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq305.png) belongs to X. Thus

belongs to X. Thus  for all

for all  . In particular, this is true for all

. In particular, this is true for all  . On the other hand, if

. On the other hand, if  then g does not contain

then g does not contain  , thus:

, thus:

contains

contains  .

.Conversely, identify  with the hyperplane

with the hyperplane  , and fix a point

, and fix a point ![$$Q =[q_1:\dots :q_n]\notin \pi (X)$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq315.png) . Consider an element

. Consider an element  that does not vanish at

that does not vanish at  and let W be the variety defined by f. The intersection of W with the line

and let W be the variety defined by f. The intersection of W with the line  is a finite set

is a finite set  . Moreover no

. Moreover no  can belong to X, since

can belong to X, since  is empty. Thus, by Lemma 10.3.3, there exists

is empty. Thus, by Lemma 10.3.3, there exists  that does not vanish at any

that does not vanish at any  . Consider the resultant

. Consider the resultant  . By Proposition 10.2.7, h belongs to the radical of the ideal generated by f, g, thus it belongs to J, which is a radical ideal. Moreover h does not contain the variable

. By Proposition 10.2.7, h belongs to the radical of the ideal generated by f, g, thus it belongs to J, which is a radical ideal. Moreover h does not contain the variable  . Thus

. Thus  . Finally, from Proposition 10.2.5 it follows that

. Finally, from Proposition 10.2.5 it follows that  . Then Q does not belong to the variety defined by

. Then Q does not belong to the variety defined by  .

.

Remark 10.3.5

A direct consequence of Theorem 10.3.4 is that the projection  is a closed map, in the Zariski topology.

is a closed map, in the Zariski topology.

Indeed any closed subset Y of a projective variety X is itself a projective variety, thus by Theorem 10.3.4 the image of Y in  is Zariski closed.

is Zariski closed.

We can repeat all the constructions of this section by selecting any variable  instead of

instead of  and performing the elimination of

and performing the elimination of  . Thus we can define the i -th resultant

. Thus we can define the i -th resultant  and use it to prove that projections with center any coordinate point

and use it to prove that projections with center any coordinate point ![$$[0:\dots :0:1:0:\dots :0]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq336.png) are closed maps.

are closed maps.

10.4 Linear Projective and Multiprojective Maps

In this section, we prove that projective maps defined by linear maps of projective spaces are closed in the Zariski topology.

Remark 10.4.1

Let V, W be linear space, respectively, of dimension  .

.

The choice of a basis for V corresponds to fixing an isomorphism between V and  . Thus we can identify, after a choice of the basis, the projective space

. Thus we can identify, after a choice of the basis, the projective space  with

with  . We will use this identification to introduce all the concepts of Projective Geometry into

. We will use this identification to introduce all the concepts of Projective Geometry into  . Notice that two such identifications differ by a change of basis in

. Notice that two such identifications differ by a change of basis in  , thus they are equivalent, up to an isomorphism of

, thus they are equivalent, up to an isomorphism of  .

.

Similarly, the choice of a basis for W corresponds to fixing an isomorphism between W and  .

.

A linear map  corresponds, under the choice of a basis, to a linear map

corresponds, under the choice of a basis, to a linear map  . Thus, the study of projective maps in

. Thus, the study of projective maps in  and

and  induced by linear maps

induced by linear maps  corresponds to the study of projective maps in

corresponds to the study of projective maps in  induced by linear maps

induced by linear maps  .

.

Proposition 10.4.2

Let  be a linear map. Let

be a linear map. Let  be the projective kernel of

be the projective kernel of  and let

and let  be a projective subvariety such that

be a projective subvariety such that  . Then

. Then  induces a projective map

induces a projective map  (that we will denote again with

(that we will denote again with  ) which is a closed map in the Zariski topology.

) which is a closed map in the Zariski topology.

Proof

The map  factors through a linear surjection

factors through a linear surjection  followed by a linear injection

followed by a linear injection  . After the choice of a basis, the space

. After the choice of a basis, the space  can be identified with

can be identified with  , where

, where  , so that

, so that  can be considered as a map

can be considered as a map  and

and  as a map

as a map  . Since X does not meet the kernel of

. Since X does not meet the kernel of  , by Definition 10.1.7

, by Definition 10.1.7  induces a projection

induces a projection  . The injective map

. The injective map  defines a projective map

defines a projective map  , by Definition 10.1.1. The composition of these two maps is the projective map

, by Definition 10.1.1. The composition of these two maps is the projective map  of the claim. It is closed since it is the composition of two closed maps.

of the claim. It is closed since it is the composition of two closed maps.

Notice that the projective map  is only defined up to a change of coordinate, since it relies on the choice of a basis in

is only defined up to a change of coordinate, since it relies on the choice of a basis in  .

.

The previous result can be extended to maps from multiprojective varieties to multiprojective spaces.

Example 10.4.3

and an injective linear map

and an injective linear map  . Then the induced linear map:

. Then the induced linear map:

Of course, the same statement holds if we replace i with any index or if we mix up the indices. Moreover we can apply it repeatedly.

Similarly, consider a linear map  and a multiprojective subvariety

and a multiprojective subvariety  such that X is disjoint from

such that X is disjoint from  . Then there is an induced linear map:

. Then there is an induced linear map:  which is multiprojective and closed.

which is multiprojective and closed.

Proposition 10.4.4

Any projection  from a multiprojective space

from a multiprojective space  to any of its factor

to any of its factor  is a closed projective map.

is a closed projective map.

Proof

The map  is defined by sending

is defined by sending ![$$P=([p_{10}:\dots :p_{1a_1}],\dots ,[p_{s0}:\dots :p_{sa_s}])$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq389.png) to

to ![$$[p_{i0}:\dots ,p_{ia_i}]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq390.png) . Thus the map is defined by multihomogeneous polynomials (of multidegree 1 in the ith set of variables and 0 in the other sets).

. Thus the map is defined by multihomogeneous polynomials (of multidegree 1 in the ith set of variables and 0 in the other sets).

To prove that  is closed, we show that the image in

is closed, we show that the image in  of any multiprojective variety is a projective subvariety of

of any multiprojective variety is a projective subvariety of  . Let

. Let  be a multiprojective subvariety and let

be a multiprojective subvariety and let  . If

. If  , there is nothing to prove. Thus the claim holds if

, there is nothing to prove. Thus the claim holds if  , i.e.,

, i.e.,  is a point. We will proceed then by induction on

is a point. We will proceed then by induction on  , assuming that

, assuming that  .

.

Let Q be a point of  . Then no points of type

. Then no points of type  with

with  can belong to X. Thus X does not contain points

can belong to X. Thus X does not contain points  , with

, with  in the projective kernel of the projection from Q.

in the projective kernel of the projection from Q.

The claim now follows from Example 10.4.3.

Corollary 10.4.5

Any projection  from a multiprojective space

from a multiprojective space  to a product of some of its factors is a closed projective map.

to a product of some of its factors is a closed projective map.

10.5 The Veronese Map and the Segre Map

We introduce now two fundamental projective and multiprojective maps, which are the cornerstone, together with linear maps, of the construction of projective maps. The first map, the Veronese map, is indeed a generalization of the map built in Example 9.1.33.

We recall that a monomial is monic if its coefficient is 1.

Definition 10.5.1

Fix n, d and set  . There are exactly

. There are exactly  monic monomials of degree d in

monic monomials of degree d in  variables

variables  . Let us call

. Let us call  these monomials, for which we fixed an order.

these monomials, for which we fixed an order.

The Veronese map

of degree d in  is the map

is the map  which sends a point

which sends a point ![$$[p_0:\dots : p_n]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq416.png) to

to ![$$[M_0(p_0,\dots , p_n):\dots :M_N(p_0,\dots ,p_n)]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq417.png) .

.

Notice that a change in the choice of the order of the monic monomials produces simply the composition of the Veronese map with a change of coordinates. After choosing an order of the variables, e.g.,  , a very popular order of the monic monomials is the order in which

, a very popular order of the monic monomials is the order in which  preceeds

preceeds  if in the smallest index i for which

if in the smallest index i for which  we have

we have  . This order is called lexicographic order

, because it reproduces the way in which words are listed in a dictionary. In Sect. 13.1 we will discuss different types of monomial orderings.

. This order is called lexicographic order

, because it reproduces the way in which words are listed in a dictionary. In Sect. 13.1 we will discuss different types of monomial orderings.

Notice that we can define an analogue of a Veronese map by choosing arbitrary (nonzero) coefficients for the monomials  ’s. This is equivalent to choose a weight for the monomials. The resulting map has the same fundamental property of our Veronese map, for which we choose to take all the coefficients equal to 1.

’s. This is equivalent to choose a weight for the monomials. The resulting map has the same fundamental property of our Veronese map, for which we choose to take all the coefficients equal to 1.

Remark 10.5.2

The Veronese maps are well defined, since for any ![$$P=[p_0:\dots :p_n]\in \mathbb P^n$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq424.png) there exists an index i with

there exists an index i with  , and among the monomials there exists the monomial

, and among the monomials there exists the monomial  , which satisfies

, which satisfies  .

.

The Veronese map is injective. Indeed if ![$$P=[p_0:\dots : p_n]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq428.png) and

and ![$$Q=[q_0:\dots : q_n]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq429.png) , have the same image, then the powers of the

, have the same image, then the powers of the  ’s and the

’s and the  ’s are equal, up to a scalar multiplication. Thus, up to a scalar multiplication, one may assume

’s are equal, up to a scalar multiplication. Thus, up to a scalar multiplication, one may assume  for all i, so that

for all i, so that  , for some choice of a d-root of unit

, for some choice of a d-root of unit  . If the

. If the  ’s are not all equal to 1, then there exists a monic monomial M such that

’s are not all equal to 1, then there exists a monic monomial M such that  , thus

, thus  , which contradicts

, which contradicts  .

.

Because of its injectivity, sometimes we will refer to a Veronese map as a Veronese embedding .

The images of Veronese embeddings will be denoted as Veronese varieties .

Example 10.5.3

The Veronese map  sends the point

sends the point ![$$[x_0:x_1]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq440.png) of

of  to the point

to the point ![$$[x_0^3:x_0^2x_1:x_0x_1^2:x_1^3]\in \mathbb P^3$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq442.png) .

.

The Veronese map  sends the point

sends the point ![$$[x_0:x_1:x_2]\in \mathbb P^2$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq444.png) to the point

to the point ![$$[x_0^2:x_0x_1:x_0x_2:x_1^2:x_1x_2:x_2^2]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq445.png) (notice the lexicographic order).

(notice the lexicographic order).

Proposition 10.5.4

The image of a Veronese map is a projective subvariety of  .

.

Proof

We define equations for  .

.

Consider  -tuples of nonnegative integers

-tuples of nonnegative integers  ,

,  and

and  , with the following property:

, with the following property:

and

and  for all i. Define

for all i. Define  , where

, where  , Clearly

, Clearly  . For any choice of

. For any choice of  , the monic monomial

, the monic monomial  corresponds to a coordinate in

corresponds to a coordinate in  . Call

. Call  the coordinate corresponding to A. Define in the same way

the coordinate corresponding to A. Define in the same way  and then also

and then also  . The polynomial:

. The polynomial:

![$$Q=v_{n,d}([\alpha _0:\dots :\alpha _n])$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq463.png) it is easy to see that:

it is easy to see that:

appears in

appears in  with exponent

with exponent  . It follows that Y is contained in the projective subvariety W defined by the forms

. It follows that Y is contained in the projective subvariety W defined by the forms  , when A, B, C vary in the set of

, when A, B, C vary in the set of  -tuples with the property (*) above.

-tuples with the property (*) above.To see that  , take

, take ![$$Q=[m_0:\dots :m_N]\in W$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq470.png) . Each

. Each  corresponds to a monic monomial in the

corresponds to a monic monomial in the  ’s, and we assume they are ordered in the lexicographic order.

’s, and we assume they are ordered in the lexicographic order.

, corresponding to a power

, corresponding to a power  , must be nonzero. Indeed, on the contrary, assume that all the coordinates corresponding to powers vanish, and consider a minimal q such that coordinate

, must be nonzero. Indeed, on the contrary, assume that all the coordinates corresponding to powers vanish, and consider a minimal q such that coordinate  of Q is nonzero. Let

of Q is nonzero. Let  correspond to the monomial

correspond to the monomial  . Since

. Since  is not a power, there are at least two indices

is not a power, there are at least two indices  such that

such that  . Put

. Put  and

and  where

where  ,

,  and

and  for

for  . The

. The  -tuples A, B, C satisfy condition (*). One computes that

-tuples A, B, C satisfy condition (*). One computes that  with

with  ,

,  and

and  for

for  . Moreover, since

. Moreover, since  , then:

, then:

, while

, while  , since

, since  preceeds

preceeds  in the lexicographic order. It follows

in the lexicographic order. It follows  , a contradiction.

, a contradiction.Then at least one coordinate corresponding to a power is nonzero. Just to fix the ideas, assume that  , which corresponds to

, which corresponds to  in the lexicographic order, is different from 0. After multiplying the coordinates of Q by

in the lexicographic order, is different from 0. After multiplying the coordinates of Q by  , we may assume

, we may assume  . Then consider the coordinates corresponding to the monomials

. Then consider the coordinates corresponding to the monomials  . In the lexicographic order, they turn out to be

. In the lexicographic order, they turn out to be  , respectively. Put

, respectively. Put ![$$P=[1:m_1:\dots :m_n]\in \mathbb P^n$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq505.png) . We claim that Q is exactly

. We claim that Q is exactly  .

.

we have

we have  . We prove the claim by descending induction on

. We prove the claim by descending induction on  . The cases

. The cases  and

and  are clear by construction. Assume that the claim holds when

are clear by construction. Assume that the claim holds when  and take m such that

and take m such that  . In this case there exists some index

. In this case there exists some index  such that

such that  . Put

. Put  ,

,  and

and  where

where  ,

,  , and

, and  for

for  . The

. The  -tuples A, B, C satisfy condition (*). Thus

-tuples A, B, C satisfy condition (*). Thus

and

and  ,

,  , and

, and  for

for  . It follows by induction that

. It follows by induction that  ,

,  and

and

, and the claim follows.

, and the claim follows.

We observe that all the forms  are quadratic forms in the variables

are quadratic forms in the variables  ’s of

’s of  . Thus the Veronese varieties are defined in

. Thus the Veronese varieties are defined in  by quadratic equations.

by quadratic equations.

Example 10.5.5

. The monic monomials of degree three in 2 variable are (in lexicographic order):

. The monic monomials of degree three in 2 variable are (in lexicographic order):

![$$Q=[3:6:12:24]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq538.png) , which satisfies the previous equations. Since the coordinate

, which satisfies the previous equations. Since the coordinate  corresponding to

corresponding to  is equal to

is equal to  , we divide the coordinates of Q by 3 and obtain

, we divide the coordinates of Q by 3 and obtain ![$$Q=[1:2:4:8]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq542.png) . Then

. Then ![$$Q=v_{1,3}([1:2])$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq543.png) , as one can check directly.

, as one can check directly.Example 10.5.6

(the classical Veronese surface) are given by:

(the classical Veronese surface) are given by:

![$$Q=[0:0:0:1:-2:4]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq545.png) satisfies the equations, and indeed it is equal to

satisfies the equations, and indeed it is equal to ![$$v_{2,2}([0:1:-2]).$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq546.png) Notice that in this case, to recover the preimage of Q, one needs to replace

Notice that in this case, to recover the preimage of Q, one needs to replace  with

with  in the procedure of the proof of Proposition 10.5.4, since the coordinate corresponding to

in the procedure of the proof of Proposition 10.5.4, since the coordinate corresponding to  is 0.

is 0.As a consequence of Proposition 10.5.4, one gets the following result.

Theorem 10.5.7

All the Veronese maps are closed in the Zariski topology.

Proof

We need to prove that the image in  of a projective subvariety of

of a projective subvariety of  is a projective subvariety of

is a projective subvariety of  .

.

First notice that if F is a monomial of degree kd in the variables  of

of  , then it can be written (usually in several ways) as a product of k monomials of degree d in the

, then it can be written (usually in several ways) as a product of k monomials of degree d in the  ’s, which corresponds to a monomial of degree k in the coordinates

’s, which corresponds to a monomial of degree k in the coordinates  of

of  . Thus, any form f of degree kd in the

. Thus, any form f of degree kd in the  ’s can be rewritten as a form of degree k in the coordinates

’s can be rewritten as a form of degree k in the coordinates  ’s.

’s.

Take now a projective variety  and let

and let  be homogeneous generators for the homogeneous ideal of X. Call

be homogeneous generators for the homogeneous ideal of X. Call  the degree of

the degree of  and let

and let  be the smallest multiple of d bigger or equal to

be the smallest multiple of d bigger or equal to  . Then consider all the products

. Then consider all the products  ,

,  . These products are homogeneous forms of degree

. These products are homogeneous forms of degree  in the

in the  ’s. Moreover a point

’s. Moreover a point  satisfies all the equations

satisfies all the equations  if and only if it satisfies

if and only if it satisfies  , since at least one coordinate

, since at least one coordinate  of P is nonzero.

of P is nonzero.

With the procedure introduced above, transform arbitrarily each form  in a form

in a form  of degree k in the variables

of degree k in the variables  ’s. Then we claim that

’s. Then we claim that  is the subvariety of

is the subvariety of  defined by the equations

defined by the equations  . Since

. Since  is closed in

is closed in  , this will complete the proof.

, this will complete the proof.

Indeed let Q be a point of  . The coordinates of Q are obtained by the coordinates of its preimage

. The coordinates of Q are obtained by the coordinates of its preimage ![$$P=[p_0:\dots :p_n]\in X\subset \mathbb P^n$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq583.png) by computing in P all the monomials of degree d in the

by computing in P all the monomials of degree d in the  ’s. Thus

’s. Thus  for all i, j if and only if

for all i, j if and only if  for all i, j, i.e., if and only if

for all i, j, i.e., if and only if  for all i. The claim follows.

for all i. The claim follows.

Example 10.5.8

and let X be the line in

and let X be the line in  defined by the equation

defined by the equation  . Since f has degree 1, consider the products:

. Since f has degree 1, consider the products:

by the previous three linear forms and the six quadratic forms of Example 10.5.6, that define

by the previous three linear forms and the six quadratic forms of Example 10.5.6, that define  .

.Next, let us turn to the Segre embeddings.

Definition 10.5.9

Fix  and

and  . There are exactly

. There are exactly  monic monomials of multidegree

monic monomials of multidegree  (i.e., multilinear forms) in the variables

(i.e., multilinear forms) in the variables  . Let us choose an order and denote with

. Let us choose an order and denote with  these monomials.

these monomials.

The Segre map

of  is the map

is the map  which sends a point

which sends a point ![$$P=([p_{10}:\dots : p_{1n_1}], \dots ,[p_{n0}:\dots :p_{na_n}])$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq602.png) to

to ![$$[M_0(P):\dots :M_N(P)]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq603.png) .

.

The map is well defined, since for any  there exists

there exists  , and among the monomials there is

, and among the monomials there is  , which satisfies

, which satisfies  .

.

Notice that when  , then the Segre map is the identity.

, then the Segre map is the identity.

Proposition 10.5.10

The Segre maps are injective.

Proof

Make induction on n, the case  being trivial.

being trivial.

![$$\begin{aligned} P&=([p_{10}:\dots : p_{1a_1}], \dots ,[p_{n,0}:\dots :p_{n,a_n}]), \\ Q&=([q_{10}:\dots : q_{1a_1}], \dots ,[q_{n,0}:\dots :q_{n,a_n}]) \end{aligned}$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_Equ22.png)

. The monomial

. The monomial  does not vanish at P, hence also

does not vanish at P, hence also  .

. . Our first task is to show that

. Our first task is to show that  for

for  , so that

, so that ![$$[p_{11}:\dots : p_{1a_1}]= [q_{11}:\dots : q_{1a_1}]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq616.png) . Define

. Define  . Then

. Then  and:

and:

, the monomials

, the monomials  satisfy:

satisfy:

so that

so that  for all i. Thus

for all i. Thus ![$$[p_{10}:\dots : p_{1a_1}]=[q_{10}:\dots : q_{1a_1}]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq623.png) .

.We can repeat the argument for the remaining factors ![$$[p_{i0}:\dots : p_{ia_i}]=[q_{i0}:\dots : q_{ia_i}]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq624.png) of P, Q (

of P, Q ( ), obtaining

), obtaining  .

.

Because of its injectivity, sometimes we will refer to a Segre map as a Segre embedding .

The images of Segre embeddings will be denoted as Segre varieties .

Example 10.5.11

The Segre embedding  of

of  to

to  sends the point

sends the point ![$$([x_0:x_1],[y_0:y_1])$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq631.png) to

to ![$$[x_0y_0:x_0y_1:x_1y_0:x_1y_1]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq632.png) .

.

of

of  to

to  sends the point

sends the point ![$$([x_{10}:x_{11}],[x_{20}:x_{21}:x_{22}])$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq636.png) to the point:

to the point:![$$ [x_{10}x_{20}:x_{10}x_{21}:x_{10}x_{22}:x_{11}x_{20}:x_{11}x_{21}:x_{11}x_{22}]. $$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_Equ25.png)

sends the point

sends the point ![$$P=([x_{10}:x_{11}], [x_{20}:x_{21}],[x_{30}:x_{31}])$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq638.png) to the point:

to the point:![$$ [x_{10}x_{20}x_{30}:x_{10}x_{20}x_{31}:x_{10}x_{21}x_{30}:x_{10}x_{21}x_{31}: x_{11}x_{20}x_{30}:x_{11}x_{20}x_{31}:x_{11}x_{21}x_{30}:x_{11}x_{21}x_{31}]. $$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_Equ26.png)

Recall the general notation that with [n] we denote the set  .

.

Proposition 10.5.12

The image of a Segre map is a projective subvariety of  .

.

Since the set of tensors of rank one corresponds to the image of a Segre map, the proof of the proposition is essentially the same as the proof of Theorem 6.4.13. We give the proof here, in the terminology of maps, for the sake of completeness.

Proof

We define equations for  .

.

define the form

define the form  of multidegree

of multidegree  as follows:

as follows:

![$$J\subset [n]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq645.png) and two n-tuples of nonnegative integers

and two n-tuples of nonnegative integers  and

and  . Define

. Define  as the n-tuple

as the n-tuple  such that:

such that:

, where

, where  is the complement of J in [n]. Thus

is the complement of J in [n]. Thus  , where:

, where:

is homogeneous of degree 2 in the coordinates of

is homogeneous of degree 2 in the coordinates of  . We claim that the projective variety defined by the forms

. We claim that the projective variety defined by the forms  , for all possible choices of A, B, J as above, is exactly equal to Y.

, for all possible choices of A, B, J as above, is exactly equal to Y.![$$ Q=s_{a_1,\dots ,a_n}([q_{10}:\dots :q_{1a_1}],\dots ,[q_{n0}:\dots :q_{na_n}]) $$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_Equ31.png)

and

and  are equal to the product

are equal to the product

.

.To see the converse, we make induction on the number n of factors. The claim is obvious if  , for in this case the equations

, for in this case the equations  are trivial and the Segre map is the identity on

are trivial and the Segre map is the identity on  .

.

Assume that the claim holds for  factors. Take

factors. Take ![$$Q=[m_0:\dots :m_N]\in W$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq663.png) . Each

. Each  corresponds to a monic monomial

corresponds to a monic monomial  of multidegree

of multidegree  in the

in the  ’s. Fix a coordinate m of Q different from 0. Just to fix the ideas, we assume that m corresponds to

’s. Fix a coordinate m of Q different from 0. Just to fix the ideas, we assume that m corresponds to  . If m corresponds to another multilinear form, the argument remains valid, it just requires heavier notation.

. If m corresponds to another multilinear form, the argument remains valid, it just requires heavier notation.

Consider the point  obtained from Q by deleting all the coordinates corresponding to multilinear forms in which the last factor is not

obtained from Q by deleting all the coordinates corresponding to multilinear forms in which the last factor is not  . If we consider

. If we consider  , then

, then  can be considered as a point in

can be considered as a point in  , moreover the coordinates of

, moreover the coordinates of  satisfy all the equation

satisfy all the equation  , where

, where  are

are  -tuples

-tuples  and

and ![$$J'\subset [n-1]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq679.png) . It follows by induction that

. It follows by induction that  corresponds to the image of some

corresponds to the image of some  in the Segre embedding in

in the Segre embedding in  .

.

![$$P'=([p_{10}:\dots :p_{1a_1}],\dots ,[p_{n-1\, 0}:\dots :p_{n-1\, a_{n-1}}])$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq683.png) . Since

. Since  , i.e., the coordinate of

, i.e., the coordinate of  corresponding to m is nonzero, then we must have

corresponding to m is nonzero, then we must have  for all

for all  . Let

. Let  ,

,  , be the coordinate of Q corresponding to the multilinear form

, be the coordinate of Q corresponding to the multilinear form  . Then we prove that the coordinate

. Then we prove that the coordinate  corresponding to

corresponding to  satisfies

satisfies

![$$ P=([p_{10}:\dots :p_{1a_1}],\dots ,[p_{n-1\, 0}:\dots :p_{n-1\, a_{n-1}}], [p_{n0}:\dots :p_{na_n}]), $$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_Equ34.png)

for all

for all  .

.To prove the claim, take  ,

,  and

and  . Then we have

. Then we have  and

and  for

for  , while

, while  and

and  . Thus

. Thus  ,

,  ,

,  and, by induction

and, by induction  . Since

. Since  , the claim follows.

, the claim follows.

We observe that all the forms  are quadratic forms in the variables

are quadratic forms in the variables  ’s of

’s of  . Thus the Segre varieties are defined in

. Thus the Segre varieties are defined in  by quadratic equations.

by quadratic equations.

Example 10.5.13

. The 4 variables

. The 4 variables  in

in  correspond, respectively, to the multilinear forms

correspond, respectively, to the multilinear forms

and

and  , we get that

, we get that  . Thus

. Thus  corresponds to

corresponds to  ,

,  corresponds to

corresponds to  ,

,  corresponds to

corresponds to  and

and  corresponds to

corresponds to  . We get thus the equation:

. We get thus the equation:

Hence the image of  is the variety defined in

is the variety defined in  by the equation

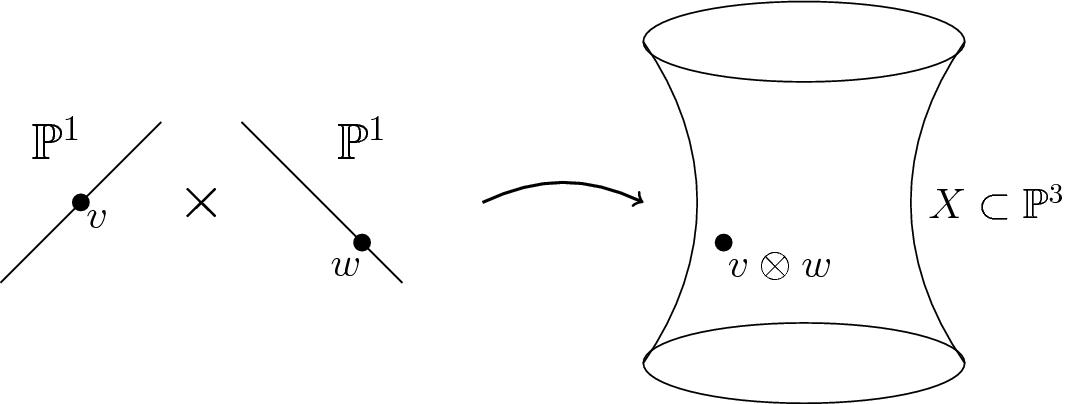

by the equation  . It is a quadric surface (see Fig. 10.1).

. It is a quadric surface (see Fig. 10.1).

Segre embedding of  in

in

Example 10.5.14

(up to trivialities) are given by:

(up to trivialities) are given by:

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  .

.Example 10.5.15

We can give a more direct representation of the equations defining the Segre embedding of the product of two projective spaces  .

.

Namely, we can plot the coordinates of  in a

in a  matrix, putting in the entry ij the coordinate corresponding to

matrix, putting in the entry ij the coordinate corresponding to  .

.

Conversely, any matrix  (except for the null matrix) corresponds uniquely to a set of coordinates for a point

(except for the null matrix) corresponds uniquely to a set of coordinates for a point  . Thus we can identify

. Thus we can identify  with the projective space over the linear space of matrices of type

with the projective space over the linear space of matrices of type  over

over  .

.

and

and  (choosing

(choosing  we get the same equation, up to the sign) produces a form equivalent to the

we get the same equation, up to the sign) produces a form equivalent to the  minor:

minor:

Thus, the image of a Segre embedding of two projective space can be identified with the set of matrices of rank 1 (up to scalar multiplication) in a projective space of matrices.

As a consequence of Proposition 10.5.12, one gets the following result.

Theorem 10.5.16

All the Segre maps are closed in the Zariski topology.

Proof

We need to prove that the image in  of a multiprojective subvariety X of

of a multiprojective subvariety X of  is a projective subvariety of

is a projective subvariety of  .

.

First notice that if F is a monomial of multidegree  in the variables

in the variables  of V, then it can be written (usually in several ways) as a product of k multilinear forms in the

of V, then it can be written (usually in several ways) as a product of k multilinear forms in the  ’s, which corresponds to a monomial of degree d in the coordinates

’s, which corresponds to a monomial of degree d in the coordinates  of

of  . Thus, any form f of multidegree

. Thus, any form f of multidegree  in the

in the  ’s can be rewritten as a form of degree d in the coordinates

’s can be rewritten as a form of degree d in the coordinates  ’s.

’s.

Take now a projective variety  and let

and let  be multihomogeneous generators for the ideal of X. Call

be multihomogeneous generators for the ideal of X. Call  the multidegree of

the multidegree of  and let

and let  . Consider all the products

. Consider all the products  . These products are multihomogeneous forms of multidegree

. These products are multihomogeneous forms of multidegree  in the

in the  ’s. Moreover a point

’s. Moreover a point  satisfies all the equations

satisfies all the equations  if and only if it satisfies

if and only if it satisfies  , since for all i at least one coordinate

, since for all i at least one coordinate  of P is nonzero.

of P is nonzero.

With the procedure introduced above, transform arbitrarily each form  in a form

in a form  of multidegree

of multidegree  in the variables of

in the variables of  . Then we claim the

. Then we claim the  is the subvariety of

is the subvariety of  defined by the equations

defined by the equations  . Since

. Since  is closed in

is closed in  , this will complete the proof.

, this will complete the proof.

To prove the claim, let Q be a point of  . The coordinates of Q are obtained by the coordinates of its preimage

. The coordinates of Q are obtained by the coordinates of its preimage ![$$P=([p_{10}:\dots :p_{1n_1}],\dots ,[p_{n0}:\dots :p_{na_n}]\in X\subset V$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq785.png) by computing all the multilinear forms in the

by computing all the multilinear forms in the  ’s at P. Thus

’s at P. Thus  for all

for all  if and only if

if and only if  for all k. The claim follows.

for all k. The claim follows.

Example 10.5.17

defined by the multihomogeneous form

defined by the multihomogeneous form  of multidegree (1, 2). Then we have:

of multidegree (1, 2). Then we have:

that defines

that defines  in

in  , define the image of X in the Segre embedding.

, define the image of X in the Segre embedding.Remark 10.5.18

Even if we take a minimal set of forms  ’s that define

’s that define  , with the procedure of Theorem 10.5.16 we do not find, in general, a minimal set of forms that define

, with the procedure of Theorem 10.5.16 we do not find, in general, a minimal set of forms that define  .

.

Indeed the ideal generated by the forms  constructed in the proof of Theorem 10.5.16 needs not, in general, to be radical or even saturated.

constructed in the proof of Theorem 10.5.16 needs not, in general, to be radical or even saturated.

We end this section by pointing out a relation between the Segre and the Veronese embeddings of projective and multiprojective spaces.

Definition 10.5.19

A multiprojective space  is cubic

if

is cubic

if  for all i.

for all i.

We can embed  into the cubic multiprojective space

into the cubic multiprojective space  (n times) by sending each point P to

(n times) by sending each point P to  . We will refer to this map as the diagonal embedding. It is easy to see that the diagonal embedding is an injective multiprojective map.

. We will refer to this map as the diagonal embedding. It is easy to see that the diagonal embedding is an injective multiprojective map.

Example 10.5.20

Consider the cubic product  and the diagonal embedding

and the diagonal embedding  .

.

The point ![$$P=[p_0:p_1]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq807.png) of

of  is mapped to

is mapped to ![$$([p_0:p_1],[p_0:p_1])\in \mathbb P^1\times \mathbb P^1$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq809.png) . Thus the Segre embedding of

. Thus the Segre embedding of  , composed with

, composed with  , sends P to the point

, sends P to the point ![$$[p_0^2:p_0p_1:p_1p_0:p_1^2]\in \mathbb P^3$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq812.png) .

.

We see that the coordinates of the image have a repetition: the second and the third coordinates are equal, due to the commutativity of the product of complex numbers. In other words the image  satisfies the linear equation

satisfies the linear equation  in

in  .

.

We can get rid of the repetition if we project  by forgetting the third coordinate, i.e., by taking the map

by forgetting the third coordinate, i.e., by taking the map  that maps

that maps  to

to  . The projective kernel of this map is the point [0 : 0 : 1 : 0], which does not belong to

. The projective kernel of this map is the point [0 : 0 : 1 : 0], which does not belong to  , since

, since ![$$P=[p_0:p_1]\in \mathbb P^1$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq821.png) cannot have

cannot have  . Thus we obtain a well defined projection

. Thus we obtain a well defined projection  .

.

The composition  corresponds to the map which sends

corresponds to the map which sends ![$$[p_0:p_1]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq825.png) to

to ![$$[p_0^2:p_0p_1:p_1^2]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq826.png) . In other words

. In other words  is the Veronese embedding

is the Veronese embedding  of

of  in

in  .

.

The previous example generalizes to any cubic Segre product.

Theorem 10.5.21

Consider a cubic multiprojective space  , with

, with  factors. Then the Veronese embedding

factors. Then the Veronese embedding  of degree r corresponds to the composition of the diagonal embedding

of degree r corresponds to the composition of the diagonal embedding  , the Segre embedding

, the Segre embedding  and one projection.

and one projection.

Proof

For any ![$$P=[p_0:\dots :p_n]\in \mathbb P^n$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq836.png) the point

the point  has repeated coordinates. Indeed for any permutation

has repeated coordinates. Indeed for any permutation  on [r] the coordinate corresponding to

on [r] the coordinate corresponding to  of

of  is equal to

is equal to  , hence its equal to the coordinate corresponding to

, hence its equal to the coordinate corresponding to  . To get rid of these repetition, we can consider coordinates corresponding to multilinear forms

. To get rid of these repetition, we can consider coordinates corresponding to multilinear forms  that satisfy:

that satisfy:

(**)  .

.

By easy combinatorial computations, the number of these forms is equal to  . Forgetting the variables corresponding to multilinear forms that do not satisfy condition (**) is equivalent to take a projection

. Forgetting the variables corresponding to multilinear forms that do not satisfy condition (**) is equivalent to take a projection  , where

, where  . The kernel of this projections is the set of

. The kernel of this projections is the set of  -tuples in which the coordinates corresponding to linear forms that satisfy (**) are all zero. Among these coordinates there are those for which

-tuples in which the coordinates corresponding to linear forms that satisfy (**) are all zero. Among these coordinates there are those for which  ,

,  . So

. So  cannot meet the projective kernel of

cannot meet the projective kernel of  , because that would imply

, because that would imply  .

.

Thus  is well defined for all

is well defined for all  . The coordinate of

. The coordinate of  corresponding to

corresponding to  is equal to

is equal to  , where, for

, where, for

, is the number in which i appears among

, is the number in which i appears among  . Then

. Then  .

.

It is clear then that computing  corresponds to computing (once) in P all the monomials of degree r in

corresponds to computing (once) in P all the monomials of degree r in  .

.

10.6 The Chow’s Theorem

We prove in this section the Chow’s theorem: every projective or multiprojective map is closed in the Zariski topology.

Proposition 10.6.1

Every projective map  factors through a Veronese map, a change of coordinates and a projection.

factors through a Veronese map, a change of coordinates and a projection.

Proof

By Proposition 9.3.2, there are homogeneous polynomials ![$$f_0,\dots , f_m \in \mathbb C[x_0,\dots , x_n]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq867.png) of the same degree d, which do not vanish simultaneously at any point

of the same degree d, which do not vanish simultaneously at any point  , and such that f is defined by the

, and such that f is defined by the  ’s. Each

’s. Each  is a linear combination of monic monomials of degree d. Hence, there exists a change of coordinates g in the target space

is a linear combination of monic monomials of degree d. Hence, there exists a change of coordinates g in the target space  of

of  such that f is equal to

such that f is equal to  followed by g and by the projection to the first

followed by g and by the projection to the first  coordinates. Notice that since

coordinates. Notice that since  for all

for all  , then the projection is well defined on the image of

, then the projection is well defined on the image of  .

.

A similar procedure holds to describe a canonical decomposition of multiprojective maps.

Proposition 10.6.2

Every multiprojective map  factors through Veronese maps, a Segre map, a change of coordinates and a projection.

factors through Veronese maps, a Segre map, a change of coordinates and a projection.

Proof

By Proposition 9.3.11, there are multihomogeneous polynomials  in the ring

in the ring ![$$\mathbb C[x_{1,0},\dots ,x_{1,a_1}, \dots , x_{n,0}\dots x_{n,a_n}]$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq881.png) of the same multidegrees

of the same multidegrees  , which do not vanish simultaneously at any point

, which do not vanish simultaneously at any point  , and such that f is defined by the

, and such that f is defined by the  ’s. Each

’s. Each  is a linear combination of products of monic monomials, of degrees

is a linear combination of products of monic monomials, of degrees  , in the set of coordinates

, in the set of coordinates  , respectively. If

, respectively. If  denotes the Veronese embedding of degree

denotes the Veronese embedding of degree  of

of  into the corresponding space

into the corresponding space  , then f factors through

, then f factors through  followed by a multilinear map

followed by a multilinear map  , which in turn is defined by multihomogeneous polynomials

, which in turn is defined by multihomogeneous polynomials  of multidegree

of multidegree  (multilinear forms). Each

(multilinear forms). Each  is a linear combination of products of n coordinates in the sets

is a linear combination of products of n coordinates in the sets  , respectively. Hence F factors through a Segre map

, respectively. Hence F factors through a Segre map  , followed by a change of coordinates in

, followed by a change of coordinates in  ,

,  which sends the linear polynomial associated to the

which sends the linear polynomial associated to the  ’s to the first

’s to the first  coordinates of

coordinates of  , and then followed by a projection to the first s coordinates.

, and then followed by a projection to the first s coordinates.

Now we are ready to state and prove the Chow’s Theorem.

Theorem 10.6.3

(Chow’s Theorem) Every projective map  is Zariski closed, i.e., the image of a projective subvariety is a projective subvariety.

is Zariski closed, i.e., the image of a projective subvariety is a projective subvariety.

Every multiprojective map  is Zariski closed.

is Zariski closed.

Proof

In view of the two previous propositions, this is just an obvious consequence of Theorems 10.5.7 and 10.5.16.

We will see, indeed, in Corollary 11.3.7, that the conclusion of Chow’s Theorem holds for any projective map  between any projective varieties.

between any projective varieties.

Example 10.6.4

defined by

defined by

, followed by the linear isomorphism

, followed by the linear isomorphism  and then followed by the projection

and then followed by the projection  to the first, second and fourth coordinate.

to the first, second and fourth coordinate.

is a projective curve in

is a projective curve in  , whose equation can be obtained by elimination theory. One can see that, in the coordinates

, whose equation can be obtained by elimination theory. One can see that, in the coordinates  of

of  ,

,  is the zero locus of

is the zero locus of

Example 10.6.5

Let us consider the subvariety Y of  , defined by the multihomogeneous polynomial

, defined by the multihomogeneous polynomial  , of multidegree (1, 0) in the coordinates

, of multidegree (1, 0) in the coordinates  of

of  . Y corresponds to

. Y corresponds to ![$$[1:1]\times \mathbb P^1$$](../images/485183_1_En_10_Chapter/485183_1_En_10_Chapter_TeX_IEq922.png) .

.

,

,

corresponds to the quadric Q in

corresponds to the quadric Q in  defined by the vanishing of the homogeneous polynomial