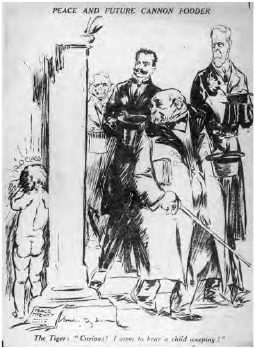

War artist Will Dyson achieves prophecy in May 1919, following the signing of the Versaille Peace Treaty, with a cartoon in which the child who will mature in 1940 weeps for his destiny, drawing bemused attention from Clemenceau of France, President Wilson and British Prime Minister Lloyd George. (Mary Evans Picture Library/AAP Image)

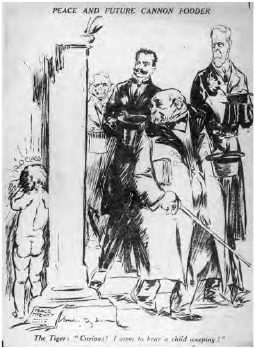

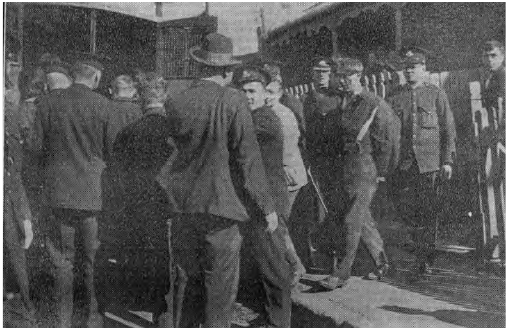

In 1920, Brigadier Gerald Campbell, a New South Wales grazier, formed the Conservative King and Empire Alliance with the tacit support of Prime Minister Billy Hughes. In May 1921, it held a monster loyalty meeting and two days later flooded Sydney’s Domain with over a hundred thousand men who stormed the platforms of the Socialist Labor Party, the Communist Party and even the ALP returned soldiers. These events foreshadowed the growth of private armies and profound divisions. (Sydney Mail, 11 May 1921, National Library of Australia)

Margaret Preston, influenced by Post-Impressionism and Cubism, produced the sort of artwork Norman Lindsay had attacked in his tracts on modernism. Prosperous by birth and marriage, in 1925 Preston produced a brilliant portrait of her maid Myra entitled The Flapper. The dress, cut to ride above the knees, was considered shocking by churchmen but was thought essential style by halfway adventurous girls. (Margaret Preston, The Flapper, 1925, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Australia, purchased with the assistance of the Cooma-Monaro Snowy River Fund 1988 © Margaret Rose Preston Estate. Licensed by Viscopy)

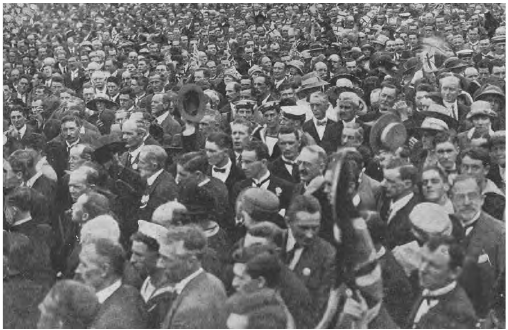

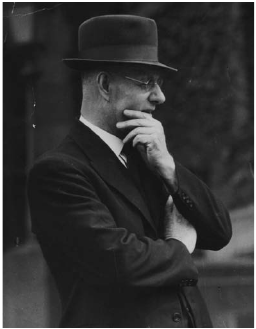

Country veteran and bush solicitor, Eric Campbell, disgruntled at lack of action by the not-so-secret Old Guard, formed the popular and numerous New Guard. Influenced by Fascist movements in Europe, he drew up plans for the kidnapping of Labor Premier of New South Wales, Jack Lang, in an era when civil war was no remote possibility. (Fairfax FXT169511)

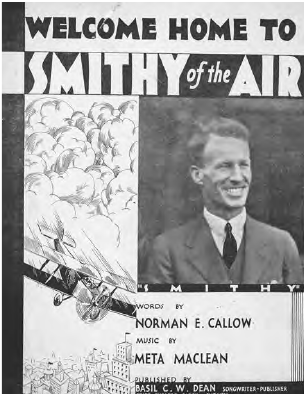

‘Smithy of the Air’ was composed and had a spate of popularity in 1930, a year when Charles Kingsford Smith would fly ten thousand solo miles and enjoyed membership in Eric Campbell’s New Guard. (National Library of Australia, nla. mus-vn5465277)

In 1927, twenty-year-old university student Beryl Mills of Western Australia became the first Miss Australia, a contest designed to promote a now defunct newspaper, the Daily Guardian. In an age of eugenics, Miss Australia was designed to represent ideal antipodean womanhood as envisaged in the age of White Australia. Heavily chaperoned by her mother on a tour of the United States, Beryl was acclaimed in San Francisco as a worthy sister to the Anzacs. (State Library of Western Australia BA287/146)

The Lindsays, Norman and Rose. Adventurous as regards theme in his writing, sketching and painting, and author of banned novels, Lindsay was a foe of both wowserism and modern art. This photograph by Harold Cazneaux, with the forthright, thin admirer and Rose as the rounded, yielding woman, seems to encapsulate his ideals of what art should be. (Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales)

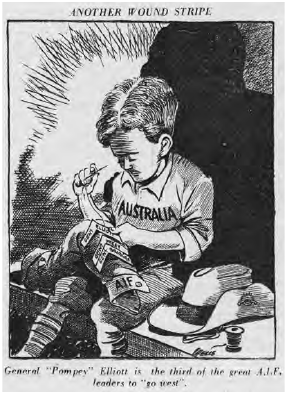

Pompey Elliott was the most famous of three AIF leaders who died by his own hand by 1931. Ironically, the wound stripe below Elliott’s on the sleeve the child is sewing is dedicated to Sir James McKay, whom Pompey despised and whose death was of natural causes, not of war neurosis. (Sunday Mail, 29 March 1931, State Library of Queensland)

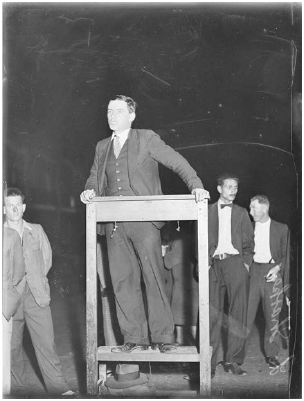

Adela Pankhurst Walsh, daughter of the leader of the Suffragette Movement, took her baby to the founding of the Communist Party in 1920, and thereafter embraced a number of radical positions, Left and Right. A strong isolationist as a new war neared, she mounted a chair to address a crowd on Japanese peaceful intentions in the Pacific. She and her husband would be interned during World War II. (Fairfax FXJ339541)

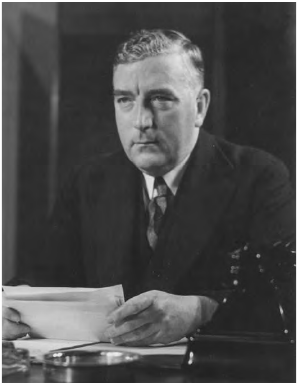

Stanley Melbourne Bruce, Melbourne soldier, businessman and Tory, was Nationalist Prime Minister of Australia from 1923 to 1929, and so the politician who moved government from Melbourne to Canberra. An urbane man, he shines here at the opening of the Canberra golf course. His influence continued in his participation in the League of Nations and as High Commissioner in London for twelve years before and during World War II. (National Library of Australia, nla.pic-vn3695870)

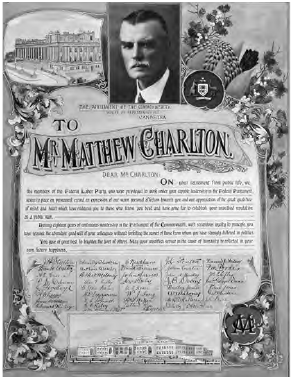

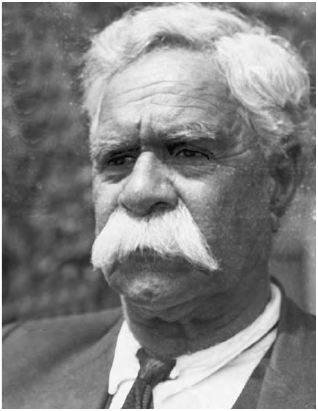

A miner from the Hunter Valley, the distinguished-looking Matthew Charlton led the Labor Party in the dog days, indeed years, from 1922 onwards. A moderate, he believed in a more independent foreign policy and in the League of Nations. By 1928, pressed by ill health and the rise of Jim Scullin, he retired from the leadership, and from parliament in 1929. It is interesting to speculate how he would have dealt with the Depression. (Newcastle Regional Library Collection, Image 345 002142)

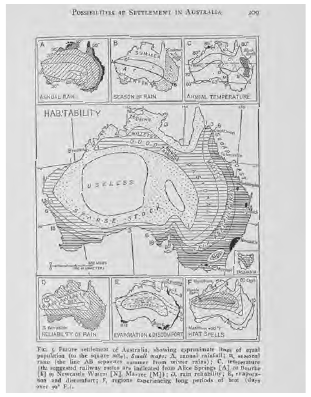

Geographer and Antarctic explorer, Griffith Taylor, committed a form of heresy against nationalist hopes for the continent when he declared the core of Australia useless and that he was under impressed with other sectors of the country. He would say in the 1920s in the United States that the term ‘Australian desert’ was ‘anathema’ to most Australians. (State Library of New South Wales, ML325/b)

Victorian Aboriginal leader, William Cooper, became a spokesman for Aboriginals denied aid in the 1920s drought and then in the Depression. Leaving his settlement to become eligible for the old age pension, he used it to fund his campaign for direct representation in parliament, the franchise, land rights and populating remote Australia with formerly dispossessed Aboriginals. In early 1938, he led the first Aboriginal deputation to a prime minister, and was the first to raise the idea of a constitutional amendment to empower the Federal government to legislate uniform Aboriginal rights. (Newspix)

Douglas Mawson, young geologist on the right, with his mentor Edgeworth David and Alistair McKay, located the South Magnetic Pole in 1909 as part of Shackleton’s Nimrod expedition. Mawson would decline an invitation from Robert Falcon Scott to join his fatal 1910 expedition and instead mounted a large expedition of his own to what would become Antarctic Australia. This and Mawson’s later BANZARE expedition of 1930 created a huge Australian Antarctic claim of 5.9 million square kilometres, over 40 per cent of the continent. (State Library of Victoria, H90.31/35)

Radio transmissions excited Australians as another weapon against distance and torpor. Here two sisters, little Jean and seventeen-year-old Dot Cheers, listen to a homemade crystal receiving radio in their back yard in Melbourne on Christmas Day 1923. Dot herself would become a radio star, broadcasting as ‘Aunty June’. (Museum of Victoria, courtesy of Dr Christina Chee, reg no. MM11115)

Western Australia expanded its population by land schemes that brought British migrants to the state. They gained and maintained their grants by living primitively and labouring long. Northcliffe, named to honour the press baron, began as such a settlement in the 1920s. Settlers such as these were required to clear their land. (State Library of Western Australia BA1881/3)

Sir Otto Niemeyer (left), the Bank of England man, came to Australia to tell State and Federal governments that, after heavy borrowings in the 1920s, they could not spend money on great public schemes to employ the poor. He seems to have survived a meeting with Premier Jack Lang in Sydney in 1930, even though Lang was the sole dissenter from Sir Otto’s message. (Fairfax FXT272525)

In the early 1930s, the Unemployed Workers Union tried to oppose what it considered unjust evictions. Increasingly, considerable forces of police were sent to break up its organised occupation of premises to which eviction notices had been sent, and the confrontations grew more and more violent. In this Newtown eviction of June 1931, the police have just pacified the occupation force of unemployed workers. (Sydney Morning Herald, 20 June 1931, National Library of Australia)

In grievous political trouble because of the Depression and the limitations on spending, Prime Minister James Scullin, addressing a Sydney crowd from the back of a truck just before the Christmas (19 December) election in 1931, holds out hope of better days if people will stick with Labor. His party would in fact be decimated, losing thirty-two seats, and the former Labor man, Joe Lyons, would lead the United Australia Party coalition thus elected to power. (Fairfax FXT22692198)

The Fascista Seziones, sections of the Italian Fascist party, were not as successful in garnering hardcore membership amongst the Australian–Italians as were the Fascios, the more informal business and social associations, and the Dopolavoro (after work) clubs. But engagement in Fascism was encouraged by Italian diplomats in Australia, where many conservatives publicly expressed their admiration of Mussolini, and in whatever form, Fascism was powerful in the Italian business and general community. This flag for the Werribee Fascista Sezione was made in 1928, and its display did not become illegal until Italy entered World War 11 in 1940. (Museum of Victoria SH940595)

The Young People Auxiliary line up to lead a Communist Party procession in August 1931 in an Australia where unemployment had climbed to one-third and Communist Party membership was rising. (Fairfax FXT269164)

The Secessionist delegates of Western Australia display the proposed flag of their independent country in London in October 1934. Backed by a successful referendum in Western Australia, they hoped that the Imperial Parliament would alter the Australian Constitution, originally an act of that parliament, in their favour. (State Library of Western Australia BA556/1)

Though the Republican side had lost the Spanish Civil War, their cause shone brightly with all anti-Fascists. In 1939, the Sane Democracy League welcomed back volunteer nurses May McFarlane and Una Wilson, who had nursed wounded Republicans during that fierce dress-rehearsal for World War II. (State Library of Western Australia 226,476PD)

Workers were still angry about the pig iron conflict of 1938 when Prime Minister Menzies visited Wollongong in 1939. Cries of ‘Pig Iron Bob’ filled the air, and police called on union leaders to help them escort Menzies through an angry crowd. (Fairfax FXJ156071)

From a studio in Melbourne in September 1939, Robert Gordon Menzies makes his well-phrased declaration of war against Germany, announcing Britain had already done so, and ‘for that reason’, a state of war existed between Australia and the Third Reich. (National Library of Australia nla.pic-an23217367)

Literally providing a lens on the war in the Western Desert, Greece and the South Pacific, the Melbourne cinematographer Damien Parer took the idea of frontline photography to a degree of skill, valour and recklessness that ensured his photographs became archetypal images of the war and that his life would not be easy or long. (Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales PXA 24, 1/a9451001)

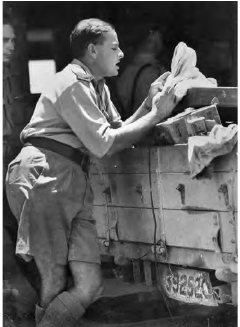

Chester Wilmott of the ABC would achieve international renown as a frontline broadcaster from within the besieged port of Tobruk. Here, in Syria in 1941, he broadcasts from the back of a truck with a cloth over the microphone to protect it from wind. (Australian War Memorial 008619)

In Hobart in September 1940, as petrol rationing begins, a car owner produces his ration cards for a service station attendant. Due to war needs for fuel, post-war shortages and economic pressure, rationing would continue for nearly ten years before being abolished by Robert Menzies, who first introduced it. It created much keenly felt inconvenience and a vigorous black market. (Newspix)

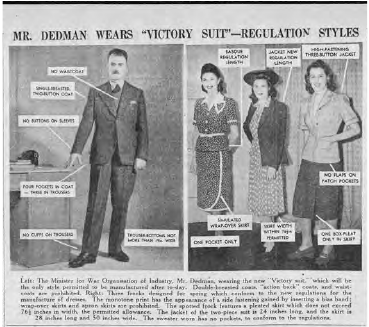

Mr Dedman, Federal Minister, wears the austere ‘Victory suit’. Double-breasted coats and waistcoats were prohibited by regulation. Three cheerful women model spring frocks for 1942, built according to exact measurements that prohibited wrap-overs and apron skirts, and pockets in sweaters. (Sydney Morning Herald, 27 July 1942, National Library of Australia)

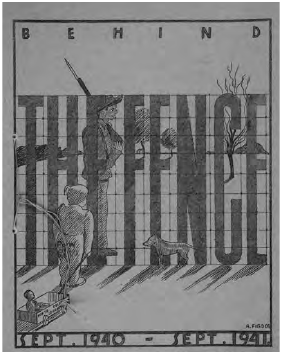

Enemy aliens were detained at a number of internment camps. This magazine was produced in Tatura camp in Victoria early in World War II, and contains articles in English and German as well as cartoons and quizzes. At Tatura, the innocent were imprisoned with the adults, sometimes themselves only questionably dangerous. (Museum of Victoria HT 15387)

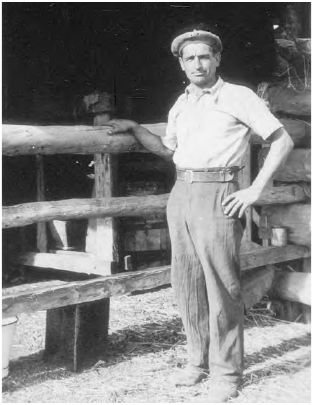

Italian POWs captured in the Middle East were men of many political beliefs. Those who were not camicie nere, blackshirt Fascists, were placed on farms to work, and remained in Australia for lack of shipping until months after the end of the Second World War. This Italian, nicknamed ‘Frisco’, worked on a dairy farm near Barmedman in New South Wales and was so happy there that he returned after the war and worked at the dairy until 1961. (Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales bcp_02815)

A member of the Women’s Auxiliary Australian Air Force, Alma Warren, and Dorothy Heitsch of the Australian Women’s Army Service, work on an aircraft engine together at the height of the Pacific War. (State Library of Victoria H98.105/533)

Kathleen Best would achieve the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel in the Women’s Medical Service. A veteran of Middle East and Greek campaigns, her nurses were subjected, while working in and escaping from Greece, to severe attacks from German aircraft. Her staging camp for nurses at Suez, guarded by wire and entered by only a single gate, was nicknamed ‘Katie’s Birdcage’. (Australian War Memorial 141181)

Something of John Curtin’s lonely burden is caught in this wartime photograph. Harried by the quarrel over bringing the Australian divisions home, tortured by fear that they would be sunk at sea, wracked by insomnia and the call of alcohol, he roamed Canberra’s streets and surrounding bush by night. He was as willing as any Australian to greet General MacArthur as a saviour. (National Library of Australia nla. pic-an23297484)

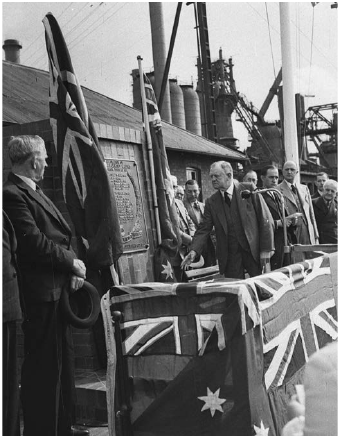

Essington Lewis, head of BHP and wartime Director of Munitions, was marked by philanthropy and a non-ideological commitment to social welfare. Appointed by Robert Menzies early in the war, he continued to work energetically with Curtin, for whom he had an abiding respect. Here, in Broken Hill in 1950, he unveils a war memorial. (State Library of New South Wales jppd_26382)

Three boy aces of the Battle of Britain created in Australian males a desire to be fighter pilots, though many of the willing young men were siphoned into Bomber Command, whose lumbering aircraft were considered the equivalent of buses, not sports cars. All three of these men would perish flying. Irishman Wing Commander Brendan ‘Paddy’ Finucane, in the middle, flying with an Australian squadron, was killed in the English Channel; Bluey Truscott, on the left, on a training exercise back home; and Thorold Smith, on the right, while rebuffing a Japanese raid on Darwin. (National Library of Australia nla. pic-vn3723178)

Max Martin, a boy from Balmain, enlisted under-age for the army and was discovered, but then rushed to the RAAF and was offered faster access to the air battles if he chose to become a gunner. A great grandson of Irish convicts, he flew ninety missions over Europe, many of them as a member of a Pathfinder squadron that marked targets at low level. Commissioned and decorated, he was appalled by the bombing of Dresden. (Judy Keneally)

Future prime minister, Gough Whitlam was a navigator in what became an elite Mitchell bomber crew. While his squadron operated against Japanese targets from Yirrkala in eastern Arnhem Land, his interest in the Yolgnu people was matched only by his enthusiasm to persuade fellow fliers to vote YES in a 1944 referendum to increase federal power. (The Whitlam Institute)

American troops were given a pocket guide to Australia with the warning that ‘when it comes to slang, the Australians can give us a head start and still win’. They should also have been warned that Australians called all United States personnel, North and South, white and black, ‘Yanks’. (National Library of Australia NL919.94UNI)

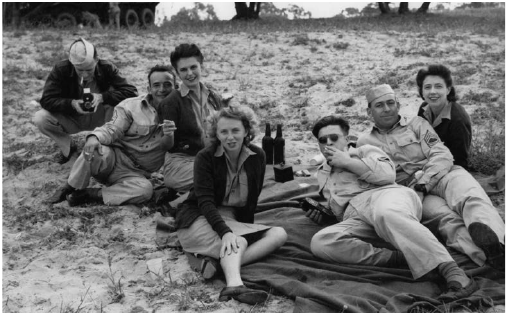

Australian girls picnic with the glamorous Yanks on a beach near a United States base close to Brisbane. These associations between Australian women and Americans would cause conflict in society, arousing the question of whether Australian women were too susceptible to Yankee glamour and trade goods. (Newspix)

Reg Saunders was the first Aboriginal soldier to be commissioned and to command a company. A veteran of the Desert War, he remained in hiding on Crete for twelve months after the island fell to the Germans. He then fought until mid-1944 in New Guinea and was commissioned as a platoon commander. In Korea, he commanded a company of the 3rd Battalion. His brother, similarly a veteran, was killed in New Guinea. (Australian War Memorial 003967)

A still believed to have been taken by Damien Parer. During the assault on Salamaua throughout mid-1943, an action designed to draw off Japanese defenders of Lae but becoming a savage battle in its own right, a burial party honours a casualty, and a soldier protects the padre’s prayer book from rain with a flap of raincoat. (Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales PXA 24,58/a9451058)

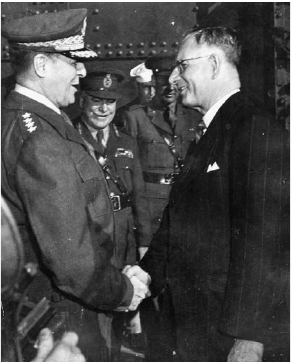

John Curtin arrives in Brisbane to consult with the American, Douglas MacArthur. Blamey, in the background, will regret the closeness between the conservative American and the Australian socialist prime minister. (Newspix)

In April 1944, an ailing and nervous John Curtin, who will become sick for most of the journey, and his shy wife, Elsie, chat with General Blamey aboard the Lurline as it departs for the United States. Curtin’s meetings with President Roosevelt and then the British would not bring quite the fruits he desired. (National Library of Australia nla.pic-vn3583643)

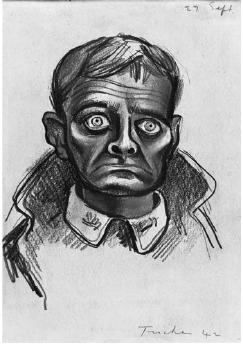

During his army service, the artist Albert Tucker was permitted to draw patients at the Heidelberg Military Hospital, near Melbourne. In this work he gives a stunning depiction of what it meant to suffer from the war neurosis described by soldiers as ‘being bomb happy’. (© Barbara Tucker. Courtesy of Barbara Tucker, Australian War Memorial ART28305)

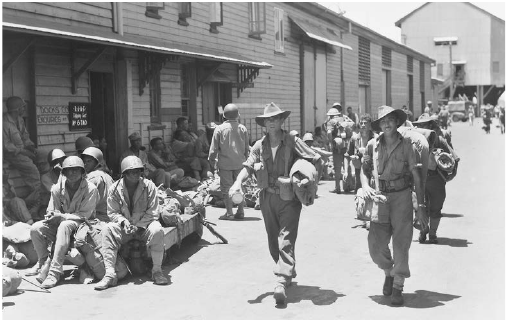

On a hot summer’s day in 1944, Australian infantrymen, returned home from New Guinea, move to their train, passing African–American soldiers, the second-class citizens of the American army, who are about to leave for the jungles these Australians have just left. (Australian War Memorial 064160)

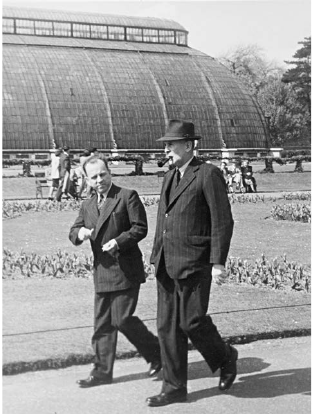

The war is over, and during an Imperial Conference in London, two men with a desire to build a new planned society, Nugget Coombs and Prime Minister Ben Chifley, go for a stroll in Regent’s Park. (National Archives of Australia M2153, 6/1)

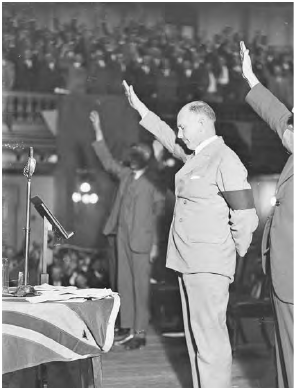

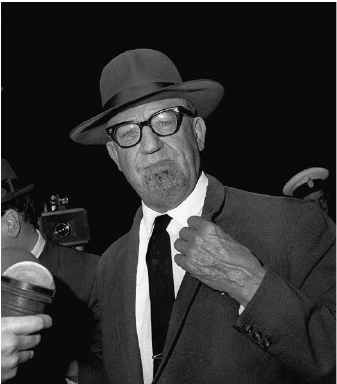

Lance Sharkey, Catholic-born Communist, addresses a crowd in Sydney on Soviet Communism after his return from the Congress of the Red International of Labour Unions in Moscow. He would follow the Kremlin in every alteration in Communist ideology, accommodating himself to the disgraceful non-aggression pact between Germany and the Soviet Union in 1939. When Prime Minister Menzies declared the Communist Party illegal in June 1940, he went underground, emerging again after the Germans invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941. (Fairfax FXT170871)

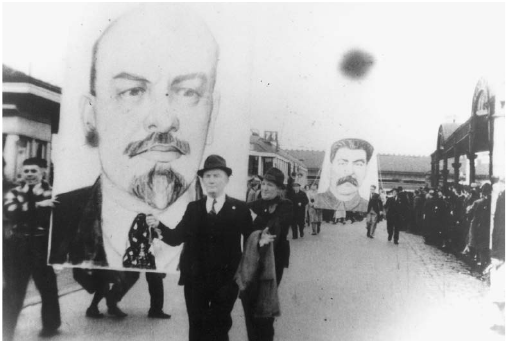

After Hitler invaded Russia in June 1942, Australian Communists, having previously condemned the war as imperialist, swung all their efforts behind the fight. Suddenly the images of Lenin and Stalin were acceptable in the general community, given that the USSR was now our ally, and the party itself, and its leaders such as Lance Sharkey, were no longer proscribed. (National Library of Australia nla.pic-an23608272)

The bitter coal strike of winter 1949 would become such a crisis for Prime Minister Ben Chifley that he took the exceptional option of sending troops to work the mines in July, causing the miners to return to work, defeated, two weeks later. The strike was one of the factors that would end Chifley’s prime ministership later in the year. (Noel Butlin Archives Centre, Australian National University: Australasian Coal and Shale Employee’s Federation, Edgar Ross Collection)

The miners’ strike of 1949 produced extensive blackouts and gas supply failure and families were reduced to seeking fuel for cooking and heat. (Newcastle Region Library, BHP Collection, Image 0020021)

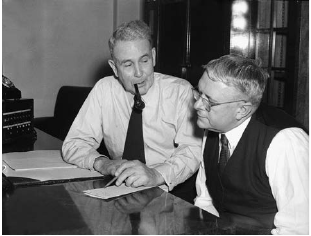

Following his defeat in the election of 1949, Ben Chifley consults Dr Bert Evatt, former Foreign minister and one of the architects of the United Nations, on the party’s future. In an Australia riven by sectarianism and anti-Communist fervour, Evatt would succeed Chifley as Labor leader, but fail to appease many Catholic members and in holding the party together. (Fairfax FXJ119728)

Young Britons transported to Australia under various schemes as a solution to their supposed economic and social disadvantage, suffered bitterly in repressive institutions from Western Australia to New South Wales. These boys at the Fairbridge Farm School at Molong, New South Wales, in 1949, are drying rabbit skins on a fence. (National Archives of Australia A1200, L11594)

Two unnamed Australian corporals of the Australian Occupation Force bring home their Japanese brides and children. Relationships between Japanese women and the occupation forces had at first been forbidden and considered as fraternisation with a recent enemy. But by 1956, when Australia had made a trade agreement with Japan, the Immigration minister allowed a crack to open in white Australia to admit ‘occupation brides’. (Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales APA 01486)

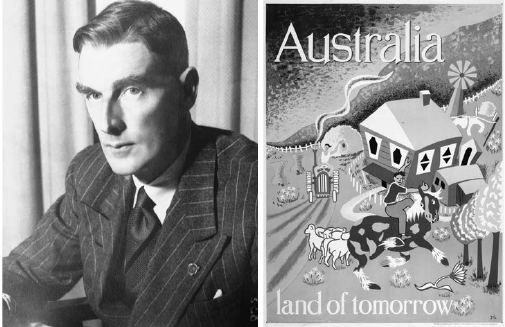

Left: William Hudson was Chief Engineer and Commissioner of the Snowy River Scheme. More than one hundred thousand workers from over thirty countries would be urged along by the tireless Hudson, who suffered the harshness of life in the Snowy along with the workers. (National Archives of Australia A11016, 358) Right: A post World War II poster aimed at attracting migrants was designed by newspaper graphic artist, Joe Greenberg. These images of the Australian idyll were hung in the grim displaced person camps in Europe and must have attracted even more than were accepted. (National Archives of Australia A434, 1949/3/21685)

Workers on the Snowy River Scheme have a party in the single men’s barracks at Island Bend in 1952. The man second from the left is a German immigrant, Karl Rieck, and his fellow German, Karl Pahl, is second from the right. (Collection: Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney. Gift of Mr Karl Rieck, 1999, PHM 99/101/2)

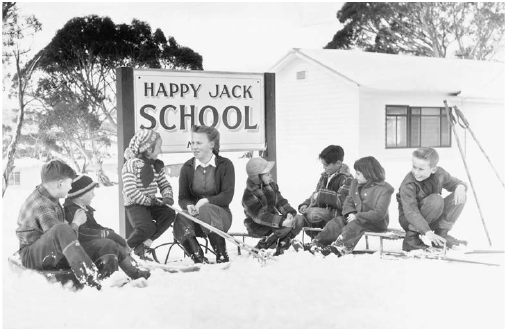

Children of workers on the Snowy River Scheme were taught at bush schools such as the Happy Jack School in Khancoban, which is seen here just after it opened in 1955. (Fairfax FXJ157257)

By 1956, displays of ethnic heritage from countries other than Britain and Ireland were becoming part of all civic ceremonies. At the Moomba Festival in Melbourne that year, the Good Neighbour Council organised a float on which candidates for the Miss New Australia appeared in national costume. As such displays became more common, all but a minority of Australia thought it appropriate that gestures of immigrant origins be made. (National Archives of Australia A12111, 1/1956/17/75)

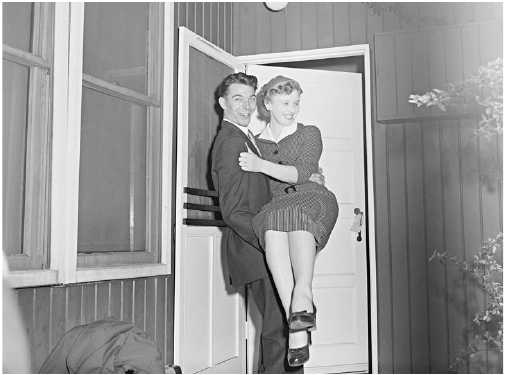

In 1955, Barbara Porritt, a pleasant but shy twenty-one year old from Redcar in Yorkshire, was credited with being the one-millionth post-war migrant, and found herself harried by the press after arriving in Melbourne aboard the liner Oronsay with her twenty-five year old husband, Dennis, an electrical fitter. Here the enthusiastic Australian press persuade Dennis to carry her over the threshold of their housing commission home. (National Archives of Australia A12111, 1/1955/4/41)

National service was introduced by Robert Menzies during the Korean War and the growing Communist infiltration of Malaya. Here a trainee named Brian Dryden of Fitzroy trips over barbed wire, to the appropriate amusement of his fellow recruits. (State Library of Victoria H98.105/4296)

Men from a Company of the 13th National Service Battalion based at Ingleburn near Sydney wait to go home after their period of national service. Such part time National Servicemen were referred to as ‘Nashos’. The scheme lasted from 1951 to 1959, but a system of conscription would be introduced again on terms of full-time duty in 1964. (Australian War Memorial P04443.007)

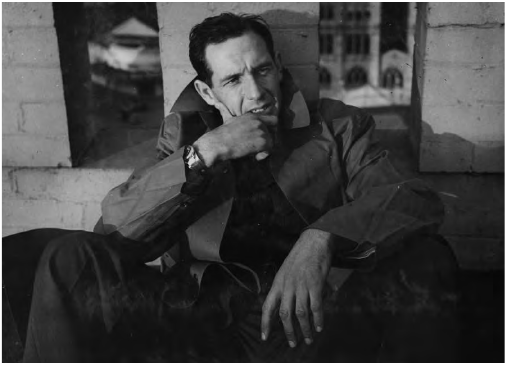

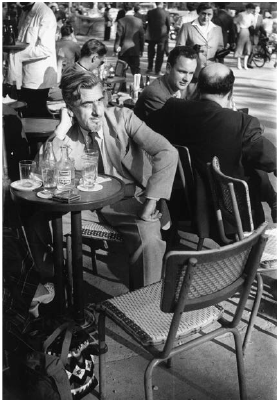

Robert Close, who first went to sea in a windjammer when he was fourteen, was a survivor of the Depression, and in an unhappy marriage when his racy Love Me Sailor was published in 1945. The following year he and his publisher were subjects of a charge of ‘obscene libel’. Sentenced to three months, he served only ten days, but thereafter moved to Paris, where he was compared to Hemingway and where this photograph was taken about 1948. (National Library of Australia nla.pic-an23609053)

At a communal washing area in Millers Point in Sydney in 1955, women take advantage of a dry day. These were typical of millions of Australian women of the period—they had heard and read of labour-saving devices, they had seen advertisements, but the miracle appliances were still beyond easy acquisition by most working people. (Fairfax/National Library of Australia/Ken Redshaw FXT162051)

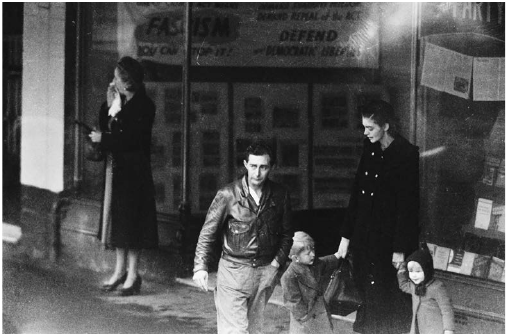

In the wake of the Communist take-over of China in 1949, surveillance of premises associated with Communism became more intense. At the stage this picture was taken by police, the Communist Party Dissolution Act was being framed by Robert Menzies’ government, though the act would be struck down by a High Court decision the following year, when the government would move to a referendum on the matter. (Surveillance of suspected Communist Party members, Police Photographers Merchant and Clarke, 26 June 1950. NSW Police Forensic Photography Archive, Justice & Police Museum, Sydney Living Museums, FP08_0158_002)

Bartolomeo (B.A.) Santamaria, son of a greengrocer of the Aeolian Islands, was founder of the Catholic Action Movement, the organisation from which the Industrial Groupers anti-Communist trade union warriors were recruited. Thus he was a catalyst for a disastrous Labor Party split in the 1950s and the emergence of the Democratic Labor Party. Combined with Santamaria’s uncompromising anti-Communism was an equally vehement call for social justice and the restriction of capitalism. (Newspix)

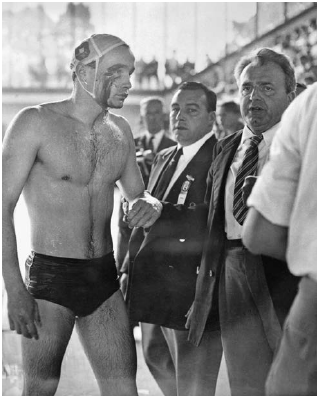

The 1956 Melbourne Olympics, as important to Australia’s assertion of identity and sporting prowess as they were, occurred at a time of intense international conflict, the Russians now having moved back into Budapest to suppress the Hungarian Revolution. When Hungary met the Soviet Union in the Olympic water polo semi-final, Ervin Zador of Hungary was only one of the Hungarian team who suffered spiteful damage in the pool, and who reciprocated. (Newspix)

The children of Melbourne were allowed an open day in the Olympic precinct and availed themselves of the chance at a gallop in this tapestry of Australian childhood past. (Newspix/State Library of Victoria H93.20/270)

Prime Minister Robert Menzies visited the Olympic Village and gave young sprinters Betty Cuthbert (right), eighteen, and Heather Innes, seventeen, a lift to the main stadium. Unlike modern similar scenes, this would have been an unscripted moment, and it delighted Australians who saw it as a gesture of social cohesion between avuncular politicians and ordinary people. It was an era too when our athletes trained in surf-fed pools and bush ovals and still won, as did Cuthbert, who would phenomenally fulfil Australian hopes by winning the 100m, 200m and relay Gold Medals. (Newspix)

The news of the coming British atomic tests on the Montebello Islands off the West Australian coast, to occur in October 1952, was kept such a secret that it was only when British war ships began arriving in Fremantle that the news got out. The leader of the ‘atomic fleet’, Rear Admiral Torlesse, complemented the people of Onslow, Western Australia, but when Perth newspapers heard the rumours, they dispatched journalists and photographers along desert tracks northwards to Onslow. (Australian War Memorial P00131.007)

In 1955 in South Australia, where atomic bombs tests were still in progress at Maralinga, the assurances of Professor Titterton, the eminent nuclear scientist, and of Minister of Supply Howard Beale, did not neutralise the scepticism and concern about the arms race of these members of the Union of Australian Women, Nan Sandy, Irene Bell, Kay Alexiou and Phyllis Powell. (State Library of South Australia B52555)

By modern standards the packaging of uranium being loaded aboard a commercial aircraft in Brisbane in 1952, by an unprotected, un-gloved airport luggage handler, seems cavalier and displays the systemic under-estimation of the peril of the tests by government and the Australian people. (Newspix/Bob Millar)

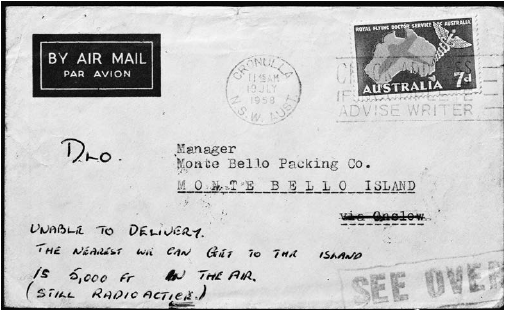

In 1952, the first nuclear device ever exploded by the United Kingdom was detonated in a bay on the main Montebello Island off Western Australia. There were two other tests in 1956. This airmail letter of 1958 carries the notation, ‘unable to deliver. The nearest we can get to the island is 5000ft in the air. Still radioactive.’ (National Archives of Australia C4078, N11350)

During the controversial British–Australia atomic bomb tests on the Australian mainland, bombs were detonated at ground level, in towers and by being dropped from aircraft. This RAF Valiant bomber dropped a bomb at Maralinga, eight hundred kilometres northwest of Adelaide, on 11 October 1956, and helped to create an environment uninhabitable by the Maralinga Tjarutja people. The release of the bomb, from a height of eleven thousand metres, was the first British launching of a nuclear weapon from an aircraft. (Newspix)

Sometimes the scientific officers at Maralinga, who wore more appropriate protective covering than many other personnel, were the ones most aware of the scale of radiation during the atomic testing in South Australia. (National Archives of Australia A6457, P214)

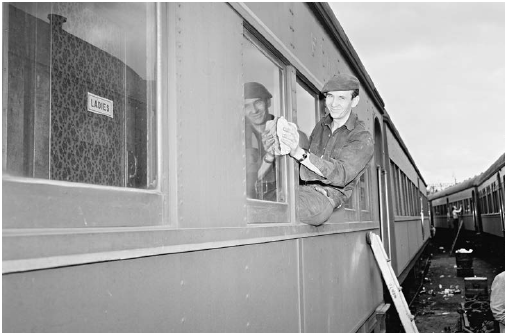

Michael Kmit, a graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków, was a displaced person in Austria by the end of the war. Under the terms of his migration to Australia in 1949, he was required to work for two years in a job as a railway porter and cleaner. Already a friend of James Gleeson, Donald Friend and Russell Drysdale, he won the Blake Prize in 1953 and the Sulman Prize in 1957. He was a major influence on the so-called ‘Charm School’ of painting, based in the Sydney mansion Merioola, that included such painters as Margaret Olley and the other ‘reffo’, Sali Herman. (National Archives of Australia A1211, 1/1953/6/7)

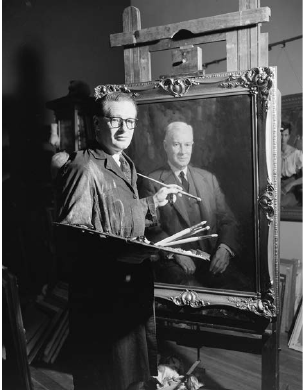

Seven-times Archibald Prize winner and World War II official war artist, William Dargie was a member of the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board at the time the Contemporary Art Society’s garnering of the first official invitation for Australia to attend the Venice Biennale. The invitation caused conflict and some embarrassment for the Australian art community. (National Archives of Australia A1200, L30134)

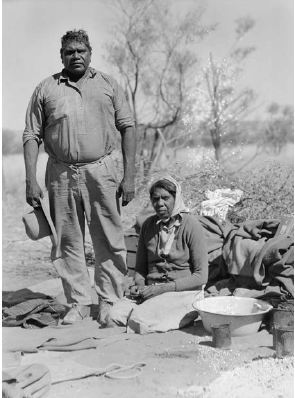

Albert Namatjira had already received renown as an artist when this picture of him and his wife was taken at a painting camp near the Hermannsburg Lutheran Mission in 1946. His marriage to Rubina in 1928 had caused a period of exile, given that she was from a prohibited ‘skin group’, and during that time he had worked as a camel driver, travelling extensively through a landscape he would become famous for depicting. (National Archives of Australia A1200, L7853)

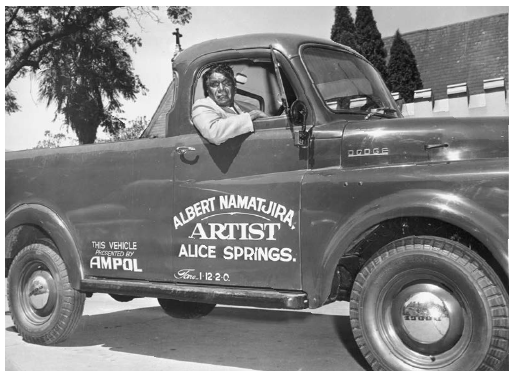

Albert Namatjira was presented with a truck by the oil company Ampol, and had by 1957 acquired full citizenship and been liberated from the restrictions that oppressed most Aboriginals. It was for carrying alcohol to a relative who still laboured under those conditions that he came to face a prison sentence. (National Library of Australia nla.pic-an24130689)

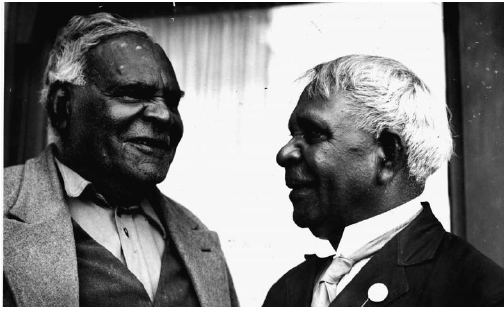

Desert Aboriginals Mark Wilson and David Unaipon attended the South Australian parliament in early 1942 to hear debate on an Aboriginals Bill aimed at a system of control of 3300 Aboriginals in South Australia. They were not happy that the normal controls on movement and employment of Aboriginals were reinforced by the legislation. (Newspix)

Pam, the young daughter of the secretary of the Australian Aborigines League, Doug Nicholls, has dressed in her best to see her father cast his vote in the 1949 federal election. This was the first federal election in which the minority of Indigenous people already registered in their states were allowed to vote. (Fairfax FXJ333271)

Pearl (Gambanyi) Gibbs, daughter of a Brewarrina Aboriginal woman and a white stockman, who spent her childhood on sheep stations, came to Sydney as a servant. Distressed by legislation which allowed the Aborigines Protection Board to confine anyone of Aboriginal blood at any of its managed stations, Pearl, seen here in 1954, began her long campaign against discrimination. (Fairfax/George Lipman FXJ72707)

Though of South Sea Islander background, Faith Bandler was often described as ‘an Aboriginal activist’. What was certain was that this persuasive woman was the face of the successful 1967 Yes vote. (Fairfax/ George Lipman FXJ2707)

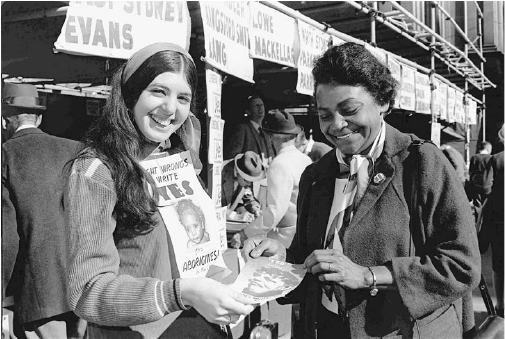

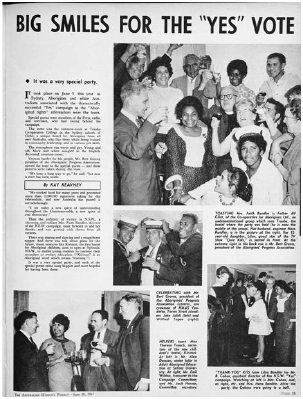

The 1967 referendum to empower the Federal government to take control of the rights of Indigenous people, ensuring standard laws throughout the nation, the franchise to all Aboriginals, and opening the door to land rights, was passed by the largest Yes vote of any referendum proposal in Australian history. (The Australian Women’s Weekly/Bauer Media Ltd)

At Green Valley in 1963, the New South Wales government opened a housing scheme for Aborigines. In this picture, Chief Secretary Kelly of New South Wales welcomes Arthur McLeod and his wife, who have moved from Worragee near Nowra. Mrs McLeod became president of the Parents and Citizens Association of the Sadlier Primary School. (Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales GPO 2 21630)

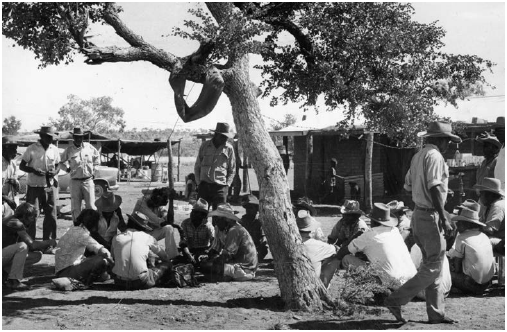

As part of their demand for land rights and wage justice, in 1966 the Gurindji stockmen sat down at the Northern Territory’s Wave Hill Station, owned by the international Vestey group. (Newspix)

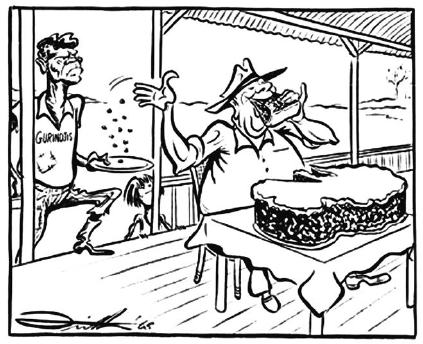

In 1968 this depiction of a Gurindji man receiving crumbs from the pastoral industry was a graphic statement of the validity Aboriginal land claims were coming to have in popular opinion. (Newspix/John Frith)

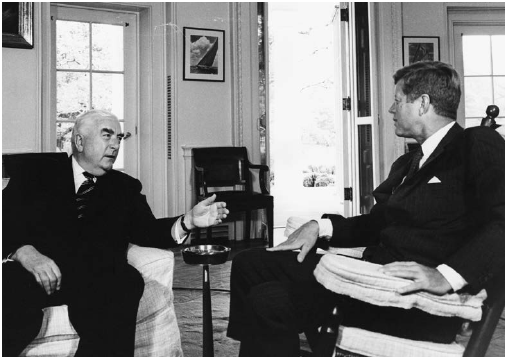

In 1962, Robert Gordon Menzies met President Kennedy on a September morning in the White House. Though one was a champion of Empire and the other a Massachusetts liberal democrat, both men were uneasy about the advance of Communism in South East Asia. (Abbie Rowe, White House Photographer. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum AR7489-B)

Labor leader Arthur Calwell had the distinction of being the only Australian political figure subjected to attempted assassination. Here he returns to Melbourne after treatment of facial wounds suffered when an unstable young man named Peter Kocan shot him in Sydney in mid-1966. Kocan, rehabilitated, would become a notable novelist. (Fairfax FXJ217389

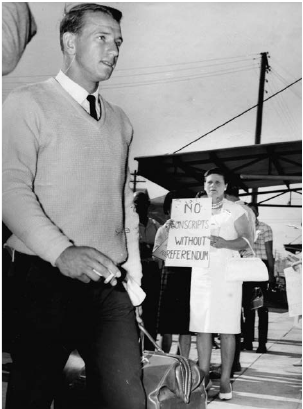

Doug Walters, the twenty-year-old Test cricketer, reports at Marrickville Barracks for induction as a conscript soldier, and passes anti-conscription protesters. As 2783873, Private Walters would not be sent to Vietnam, but while still a soldier, played against the Indians and toured England, scoring his one thousandth Test run in only his eleventh Test. (Newspix)

In early 1966, a pedestrian passes the placards of Save Our Sons in Martin Place, Sydney. The power behind the movement was the remarkable English-born Bridget Gilling, fourth from the right, who would also be involved in the founding of the Women’s Liberation Movement. (Fairfax FXJ171269)

Charles Perkins, the first Aboriginal university graduate, was leader of the Freedom Riders, a collection of students, white and black, who travelled around the state of New South Wales campaigning for an end to the segregation and exclusion of Aboriginals in places such as cinemas and pools. After fighting a hard campaign in Moree in 1965, he joins Aboriginal children in the town pool. (Newspix/Neville Whitemarsh)

By the end of the 1960s, Australian women were active in the equal pay campaign and Mrs Zelda d’Aprano made her point by chaining herself to the front doors of the Commonwealth Building in Melbourne. (Fairfax FXJ128797)

In October 1966, President Lyndon Johnson visited Australia, considering it an important ally in South Vietnam. When protesters blocked his motorcade, the colourful New South Wales Premier, Robert Askin, accompanying Johnson, shouted this advice to the driver. (Newspix)

At Nam Dong in South Vietnam in June 1964, the incisive, eloquent and vigorous leader of the Australian Army Training team, Ted Serong, inspects a mortar pit in which, the previous day, Warrant Officer Kevin Conway became the first Australian killed by enemy action. (Australian War Memorial P00963.005)

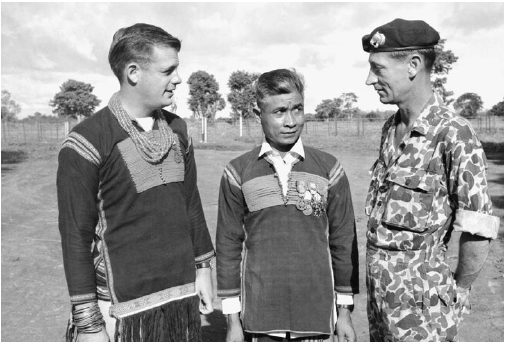

On the left, Captain Barry Petersen, a young Queenslander, had an extraordinary career as a leader of Montagnard irregulars, whose grievances he directed towards the Viet Cong. After two years of commanding the Montagnard Truong Son Force of a thousand tribesmen and having acquired the Montagnard name Dam San, Captain Petersen was brought back into the regular service. With him here is one of his Montagnard warriors, and his offsider Warrant Officer Jock Roy. (Australian War Memorial DNE_65_0428_VN)

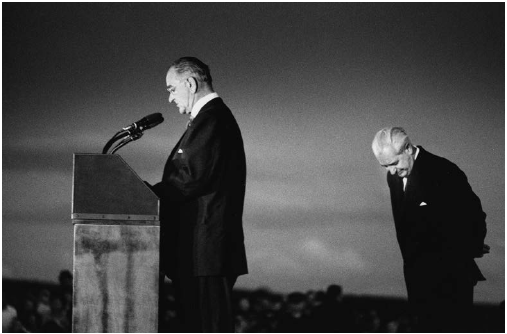

At Canberra Airport, Prime Minister Holt seems to assert his unity of intent with President Johnson, and will express it as, ‘All the way with LBJ’. The memory of American deliverance from the Japanese had been invoked but was rejected by millions of Australians. (David Moore Photography)

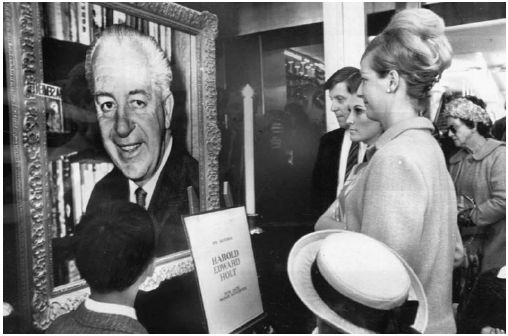

In a Melbourne store, in 1968, shoppers confront the conundrum of their Prime Minister’s tragic death, and the genial and worldly Holt, smiling back at them, seems to offer few indications of what happened. (Newspix)