In Nicaragua I experienced an extraordinary optimism, a moment in which a whole society was mobilized, uniting together as they overthrew a dictatorship. The images I made came to stand in for that optimism. If I’ve returned to Nicaragua so often, it has been to see what has remained of that hope among present generations, born after the revolution.

The building that housed the newspaper La Prensa was bombed in the last month of the war, destroying their archive. To replace some of the visual evidence, I collected images made by a number of international photographers and brought them back to Nicaragua on the first anniversary of the overthrow of Somoza. Those images became part of the Museum of the Revolution, contributing to the documentation of a history that might otherwise have been lost.

The photographs I made during the popular insurrection from 1978–1979 have become the reference for a continued relationship and sustained engagement with the people and places I once framed. I see this work as part of an archive to reexamine, revisit, and perhaps rerender. Returning is a way to reconnect.

FIGURE 10.1 Anastasio Somoza Portocarrero, with recruits of the elite infantry training school (EEBI) (July 1978), from the series Reframing History, Managua, Nicaragua, July 2004; Susan Meiselas.

Initially I gathered the publications that had used my photographs to track the different contexts in which they were seen. It was as if each image had taken on a life of its own.

Five years after the insurrection, in 1984, I curated a small show, titled Mediations, presenting three parallel narratives: in the center, the sequenced pages from my book Nicaragua: June 1978–July 1979 interrupted with a framed image that had been acquired by a museum and transformed into Art. Below were the outtakes from my selection process, and, above, I placed the tearsheets to show the images that had been chosen and published in popular international magazines.

FIGURE 10.2 Installation view from the exhibition Mediations, held at Side Gallery, Newcastle-on-Tyne, 1982–1983; Susan Meiselas.

In a sense, this is an interrogation, from and of a history; an attempt to remember and reread images. This process of inquiry continued ten years after the revolution, while making the film Pictures from a Revolution, which was a search for the people who were within the photographs that I had made, to find them and find out what had happened to them in the years that had intervened. My intention was to create a tension between the formal framed “iconic” image and the life that had gone on beyond it, following the trauma of a long war.

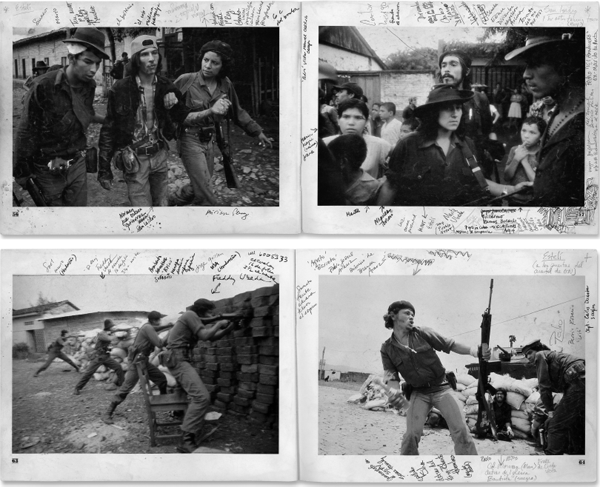

FIGURE 10.3 Nicaragua: June 1978–July 1979 (New York: Pantheon, 1981), annotated with field notes by the subject while searching for people in the photographs for Pictures from a Revolution (1991); Susan Meiselas.

Fifteen years later, I returned with the project Reframing History, in which these photographs were again reexamined, as a marking of time, a point of departure and reflection. The concept was to create a public installation, in the streets, not a permanent museum, but a temporary crossroad. The 2004 project was a collaboration with the Institute of History at the University of Central America and took place for a month in Nicaragua, around the twenty-fifth anniversary of the triumph over Somoza.

FIGURE 10.4 Youths practice throwing contact bomb s in forest surrounding Monimbo (June 1978), from the series Reframing History, Masaya, Nicaragua, July 2004; Susan Meiselas.

There were three phases to Reframing History: the most important for me was the dialogue initiated to create the actual installation of the photographs as murals in the landscape of four towns where they were first taken. The second phase was filming people looking, while gathering community reactions and recollections. The last phase was a further transformation, an exhibition throughout Europe and later New York with the murals and video creating a work of remembrance for a distant international audience who had initially experienced the war through some of these pictures.

Rather than remaining buried within an archive, the photographs were alive again. On-site, they ignited reflections that reaffirmed both my connection to Nicaragua and their own deepening historical value.