1

BUSINESS AND INDUSTRY

WIEDEMANN BREWERY

George Wiedemann was born in Eisenach, Germany, in 1833 and immigrated to the United States around 1853. He moved to Newport, Kentucky, in 1870 and founded the George Wiedemann Brewing Company. It became one of the largest brewing companies in the nation and the largest in Kentucky. A major expansion of Wiedemann’s brewing operations took place in the 1880s when he developed five acres of land at Sixth and Columbia Streets in Newport. Designed by architect Charles Vogel, it became, according to the Encyclopedia of Northern Kentucky, “one of the world’s largest and most efficient breweries.”

The Wiedemann Brewery structure became one of the most iconic and popular buildings in Northern Kentucky history. This was in part due to its magnificent size for a brewery of its time, the fame of the Wiedemann name, the popularity of the beer and its place in Northern Kentucky lore and the popularity of the old beer garden in the twentieth century. The brewery was five stories tall and included a stable that could house 150 horses. In 1893, the famous Samuel Hannaford and Sons architectural firm designed the beautiful and ornate Wiedemann offices. The brewery consisted of many iconic components, such as the curved corner, boiler and engine rooms, storage cellars, racking and wash house, main office, bottling shop, storage and garage complex, tower, stacks and brew house.

Aerial view of Wiedemann Brewery. Kenton County Public Library.

Wiedemann Brewery continued to grow and eventually was taken over by Wiedemann’s sons Charles and George Jr. However, the federal government shut the brewery down during Prohibition. Before the brewery was shut down, the federal government charged it with violation of the Volstead Act for producing 1.5 million gallons of illegal beer. The grand buildings were actually padlocked, and George Wiedemann’s grandson Carl served time in a federal penitentiary over the illegal brewing. It reopened following repeal and did very well for the next thirty years. Wiedemann kept up on technology and had the first steel fermenting tanks west of Pittsburgh in 1946. By 1967, the annual capacity stood at 900,000 barrels. However, the market changed. The number of breweries in the region went from twenty-six in 1898 to four by 1967.1 The G. Heilman Brewing Company bought Wiedemann in 1967 and closed the plant in 1983. Wiedemann ceased its independent operation after ninety-seven years. In part, the Newport plant became less efficient. There was a certain amount of pride in the community with the Wiedemann Brewery business, as well as the structure itself. Newport and Wiedemann went together; their identities were closely aligned. As the brewery was the largest employer in Newport, the city lost four hundred jobs and an eighth of its payroll tax revenue. The water department lost $100,000 in revenue.2 With this loss, Newport no longer housed the last large brewery in Northern Kentucky. It symbolized a need for the community to revitalize itself—which residents successfully did over the next couple decades. The entire structure was demolished in the 1990s, and today, part of the land is used to house the Campbell County Justice Center. It continues to live in the memory of many Northern Kentuckians who can remember the grand buildings that operated during their lifetimes. There were efforts to save the structures, and the city was awarded a federal grant to convert them to an office and retail complex. Unfortunately, those plans fell through. Even though a distant memory, the Wiedemann Brewery Complex stands as a symbol of the region’s strong brewing tradition and industrial innovation.

Beer garden at Wiedemann Brewery. Kenton County Public Library.

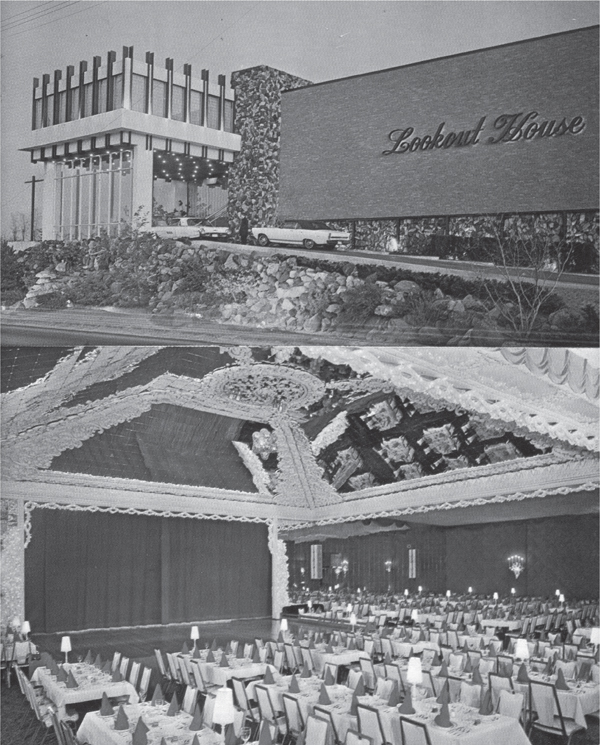

LOOKOUT HOUSE

The Lookout House was one of the great nightclubs in Northern Kentucky—with a past as interesting as it is historical. Dave Schrage, who parked cars at the Lookout House, recalls the time Tiny Tim’s limousine pulled under the large roofed carport. The carport was the main attraction of the front view of the supper club’s exterior. All parking was valet, and Schrage remembers the extreme perfume smell as he parked Tiny Tim’s limousine.

Known for its dinners, night life and gambling, the Lookout House was located on the corner of Kyles Lane and Dixie Highway in Fort Wright, Kentucky. In 1886, Aloise Hampel bought the land and opened a restaurant known for its tremendous views of Northern Kentucky and Cincinnati. As a result, it was renamed the Lookout House, but many falsely believed it was named because of its history as a lookout site for Union troops during the Civil War. Following Hampel’s death, Bill Hill bought the restaurant in 1912. Hill turned it into a flourishing nightclub. However, Prohibition caused the business to struggle. As a result, Hill sold it to Jimmy Brink, who made changes such as major remodeling and bringing live entertainment and gambling to the Lookout House. The rest is history, as they say. Since gambling was illegal, numerous charges were brought against Brink. Several high-stakes gamblers frequented the club, as well as, purportedly, members of organized crime. Brink was killed in a plane crash in 1952. It was suspicious according to the court. Brink was killed with Charles Drahmann, and both had recently testified before a federal panel investigating gambling nationwide.3 The Lookout House was sold in 1962 to Bob and Dick Schilling. The club did very well under the Schillings’ management, and famous entertainers came from around the country. One advertisement for the Lookout House, found on nkyviews. com, describes the supper club as “a focal point for the smart set from the mid-west area. Here, one can enjoy dining in a most magnificent manner. Our main dining room is the Casino Room. It will comfortably seat 500 guests, there are six other dining rooms serving the finest American foods and featuring nightly entertainment. There are also 15 other private rooms, seating from ten to 500.” Total seating capacity was said to be 1,800 guests. In 1970, Dick Schilling told Wayne Dammert, “I’ve taken this place about as far as it’s gonna go.” A month before, he purchased the site of the Beverly Hills Supper Club.4

On August 14, 1973, tragedy struck the Lookout House while it was closed for renovation. A thirteen-year-old Robert Schrage, standing on Vidot Court in Fort Wright, watched as the blaze dominated the view up the hill. The heavy smoke was engulfing the sky. With it went the building where so many Northern Kentucky residents and visitors enjoyed great food and national entertainment. Later in the year, Robert Schrage snuck into the ruins of the structure and noticed the remnants of the ornate hallway and some of the beauty of the entranceway could still be seen. It was rumored a grease fire in the kitchen started the blaze, and the Kentucky Post described it as “one of the most dramatic fires in local history.”

Lookout House from Dixie Highway. Kenton County Public Library.

The Lookout House was never rebuilt. Today, an office building and bank occupy the site.

BEVERLY HILLS SUPPER CLUB

The Beverly Hills Supper Club has two dramatic histories. First, it is the site of a famous nightclub known across the country as a spot for top-notch entertainment and excellent food. Second, it is the location of one of the most tragic fires in U.S. history.

Located just a few miles from downtown Cincinnati, the site of the former Beverly Hills Supper Club is a sad reminder of the tragedy that took place on the hill overlooking Southgate. The fire is indelibly imprinted into the memories of anyone alive at the time, especially the responders and the families of those lost.

The club began in the 1930s as a restaurant and gambling hall. Gambling is a major part of the Northern Kentucky entertainment history, and Beverly Hills was a major player. While illegal, it was a protected industry, especially by a syndicate mob. However, in 1961, George Ratterman was elected sheriff of Campbell County. He ran on a reform platform of cleaning up the small towns of Northern Kentucky. Organized crime eventually left, business suffered and the Beverly Hills Club closed. In 1969, the club was sold to Dick Schilling and his sons. Major renovation took place to reconfigure the site. According to the Encyclopedia of Northern Kentucky, a ground floor was constructed, the second floor remodeled, the casino turned into the Viennese Room and space converted into a show room and large banquet halls. In 1970, fire destroyed the interior of the building, and the Schillings started over again. After reconstruction, the building as it is remembered today was opened in 1971. In 1972, Schilling redesigned the front façade. The business thrived, and additions were constructed for the first six years of the decade. The most famous rooms were the Zebra, Viennese and Cabaret. The final addition to the building was the Garden Room. It was behind the club and overlooked the gardens. The building renovations created a “sprawling, non-linear complex of function rooms and service areas.”5

Exterior view of Beverly Hills Country Club. Kenton County Public Library.

Tragedy Strikes

May 28, 1977, is a date most longtime Northern Kentuckians will never forget. Singer and actor John Davidson was to perform in the Cabaret Room, which could hold 600 safely.6 Estimates by the fire marshal put the room above capacity, later estimated at 9007 to 1,300.8 A wedding reception party complained of excessive heat and left the Zebra Room early, and the space remained vacant until just before 9:00 p.m., when a worker opened the door to discover smoke. It quickly spread to other rooms and throughout the building. “Fire investigators later estimated that, once through the northern doors of the Zebra Room, the fire took only two to five minutes to arrive at the Cabaret Room; as a result, news of the fire and the first of the smoke and flame reached the Cabaret Room, the farthest point from the Zebra Room, nearly simultaneously.”9 Fire responders arrived quickly, and around 9:10 p.m., the lights went out, causing panic. When all was said and done, 165 people died in the Beverly Hills Supper Club fire. According to the Cincinnati Enquirer, the investigation found many construction deficiencies, including overcrowding, inadequate fire exits, faulty wiring, lack of firewalls, poor construction, safety code violations and poor regulatory oversight.10

The impact of the fire was tremendous in so many ways—perhaps none more important than the many governmental code and safety improvements that resulted. Today, the site sits vacant, resting on top of a hill overlooking I-471 and U.S. 27. Only some concrete remnants on the driveway remain. A state historical marker has been installed. On the sad hill, a large cross honors the deceased. It can be seen when driving on I-471.

THE LIBERTY THEATER

In Covington, like many urban centers of the early part of the twentieth century, citizens had several choices for movie going. The growth of movie theaters paralleled the growth of the film industry, especially from silent to talking pictures. According to Robert Webster in “A History of Northern Kentucky’s Long Forgotten Neighborhood Movie Theaters,” “[L]ive entertainment shows were the rage well into the early 1920s. Silent movies were first introduced in the late 1800s, but received little notice until the early 1900s when improved technology provided that they could be produced on a single reel.” The first movie theater in Covington was opened in 1905 on the north side of Pike and Craig Streets. Covington had four grand movie viewing options in the 1920s and ’30s. They included the Lyric Theater at 714 Madison, the Rialto (once called the Colonial and opened around 1916) at 425 Madison, the Strand on Pike Street and the Liberty between Sixth and Pike Streets.11 By 1920, over thirty movie theaters existed in Covington, Newport, Bellevue and Dayton.

Designed by architect Harry Hake, the Liberty Theater opened on July 21, 1923. Construction costs were estimated at $300,000, and the auditorium featured 1,500 blue leather seats on both the main floor and balcony. The theater also included a marble lobby and had a famous miniature Statue of Liberty. Other features were ticket booths made of mahogany, a grand staircase made of marble and brass, a large organ and a large mural of New York Harbor on the stage.12 The Liberty was financed by some important Covington businessmen: Richard Ernst, George Hill, Polk Laffoon, Frank Thorpe and L.B. Wilson. The theater was so named because it was adjacent to the new Liberty National Bank. One comment on the website Cinema Treasurers offers memories that “the Liberty had a huge selection of candies, sodas, and sandwiches and even the rest rooms were elaborate, it looked as though the rest room area itself was fit for a queen, I remember it being huge, lounging chairs & couches lining the sprawling lower level that housed it, down a luxurious sprawling staircase, rather scary and cold to a child yet inviting with its intrigue.” According to Webster, the Liberty Theater “was by far the most elegant theater building in the entire Northern Kentucky Region.”

Liberty Theater on Madison Avenue in Covington. Kenton County Public Library.

With Covington being a shopping hub of Northern Kentucky until the 1960s, parents would drop their kids off at the Liberty while they visited the department stores. The Liberty Theater closed in the 1970s. During this time, Covington saw a decline in downtown businesses. Movie theaters were also victims of the flight to the suburbs. “Long-term Covington businesses closed: Eilerman’s in 1973, Goldsmiths in 1966, and later Coppins, Marx, J.C. Penny, Montgomery Ward, Woolworth’s, and Sears.”13 Neighborhood movie theaters are now a thing of the past. The popularity of television paralleled the decline of the neighborhood theaters beginning in the late 1960s and early 1970s.14 The only one still operating as an entertainment venue is the Madison Theater in Covington, which is mostly opened for concerts. The Liberty Theater was bought by Mid-States Theaters Inc., which also bought the nearby Madison. The Liberty closed in the 1970s, and the structure was demolished by Peoples Liberty Bank for an office addition.15

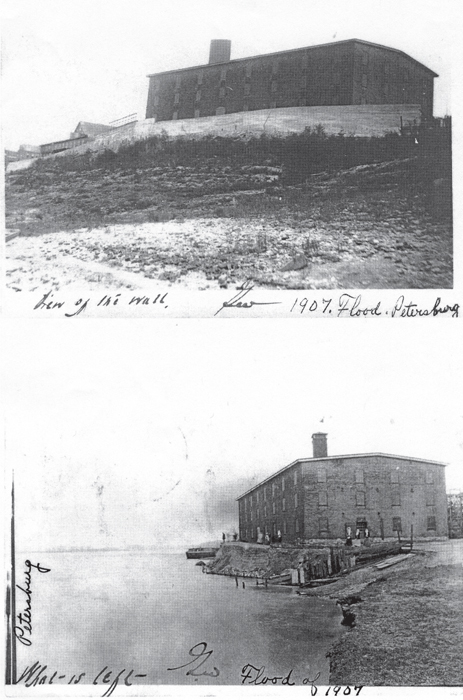

PETERSBURG DISTILLERY

The Reverend John Tanner established Tanner’s Station in an area of rural Boone County now called Petersburg. Petersburg is on the site of a Fort Ancient village from approximately AD 1200. Petersburg developed rapidly over the years, and in 1859, it had the largest population in Boone County.16 The town sits on a beautiful high bank of the Ohio River, providing not only protection from flooding but great commercial and recreational access as well.

Prosperity and growth began in the 1830s with the establishment of the Petersburg Distillery. The location of the distillery was at first the home of the Petersburg Steam Mill Company, founded in 1816. However, in 1833, the company was sold to two brothers, William and John Snyder. They quickly added a distillery, and according to Bridget Striker, Boone County Library historian, it “became an economic powerhouse in the region.” In 1860, the distillery was producing approximately 1.125 million gallons of whiskey per year.17 Snyder’s whiskey and flour were transported by the Ohio River. Despite this success, William Snyder fell on hard financial times and could not repay loans received to grow the business. Snyder sold the distillery, and his son-in-law Colonel William Appleton took over management. However, according to Striker, the Civil War and high excise taxes forced him to sell, and in 1864, 75 percent of the interest was sold to two individuals: Joseph Jenkins (50 percent) and James Gaff (25 percent). Ownership changed again with both Jenkins and Gaff selling their interests to Julius Freiberg and Levi Workman.

The whiskey industry prospered in the years to come, and the Petersburg Distillery did very well through the remainder of the century. By 1880, the Petersburg Distillery was producing more whiskey than any other in the state of Kentucky. The distillery was worth $250,000 and had a capacity of four million gallons per year; the daily capacity of twelve thousand gallons was 14 percent higher than the average Kentucky distillery in 1890.18 In 1899, the distillery was sold to the Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Company, which was buying like businesses across the state. The company started shutting down distilleries, and Petersburg survived until 1910. For the next few years, the distillery was used as a warehouse in order to distribute the remaining whiskey.

The Petersburg Distillery. Kenton County Public Library.

The buildings were dismantled. The site today has remnants of foundations, stone and walls. Three buildings remain: the distillery cooperage (on distillery site, circa 1870), the distillery scales office (circa 1859) and the superintendent’s office. According to the Encyclopedia of Northern Kentucky, “[T]he massive brick warehouses were dismantled one by one. Much of the brick was reused in construction projects outside Boone County. However, a number of buildings in Petersburg were built from distillery brick, including the tiny 1916 Petersburg Jail. Along with several houses, the National Register lists the 1913 Odd Fellows Hall and the 1916 Petersburg Baptist Church, also built of distillery brick.”

THE ALTAMONT SPRINGS HOTEL

The City of Fort Thomas was originally incorporated on February 27, 1867, under the name the District of Highlands. It was later incorporated as Fort Thomas in 1914. The beautiful city has a long and interesting history that includes Native American battles, military barracks, interesting historic figures and a retreat location. According to Sam Shelton, in an article on ftthomasmatters.com, “[T]he district of Highlands started taking shape. [Samuel] Bigstaff kept his promise of bringing his electric street cars that ran from Newport to the District of Highlands. This once desolate place started attracting people from around the area and people started moving in, building large estates. The surrounding land became a retreat for the rich and famous wanting to escape from the bustling, crowded river cities.” An area called the Midway District began developing near the site of the military fort, which began construction in 1883. These barracks were moved from Newport, where they were prone to flooding. By 1893, forty-nine buildings had been constructed at the new fort. The Midway District, according to Shelton, was made up of bars, restaurants, ice cream shops and prostitution.

However, an often overlooked part of the history of Fort Thomas is the development of hotels. The first was the Fort Thomas Hotel on South Fort Thomas Avenue. The most well known was the Altamont Springs Hotel. People would travel long distances because they believed its springs were beneficial to their health. While this belief helped make the hotel popular and successful, it may have led to its downfall. Once it was proven the springs had no health benefits, people stopped visiting. The Altamont sat on the current site of Crown Point, with a beautiful view of the Ohio River. The hotel was eventually sold to the army for the wounded and later had a few other owners. According to Shelton, “[A]fter going through several owners, the Altamont met its final match- the wrecking ball. All remains of the hotel were pushed over the hillside. To this day you can walk along the old road and stairs that once lead from the Ohio River to the famous hotel.”

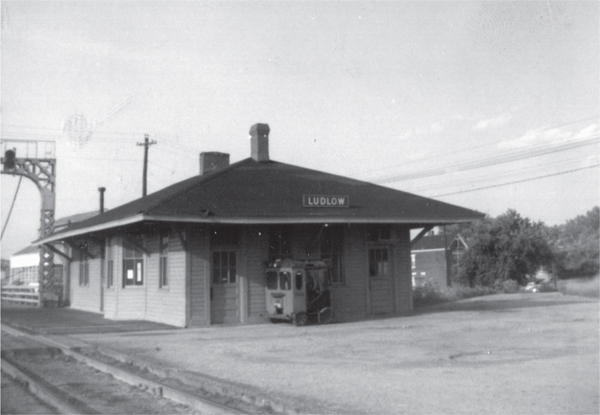

SOUTHERN RAILROAD DEPOT AT LUDLOW

The history of railroads is as much a part of Northern Kentucky as anything. It is a fascinating narrative that parallels the growth and development of the entire Northern Kentucky region. The most heartfelt aspect of the railroads to the people was the depots. Railroad depots dotted the Northern Kentucky landscape, facilitating arrivals and departures. They were also used to deliver shipments to the community and functioned as a place to get news through the Western Union telegraphs. People left via the depots to search for their fortune or fight in a war. Many came back through the depot in a casket, arriving in their hometowns for a final time. So many emotional goodbyes and hellos took place at Northern Kentucky railroad depots, which served as unofficial town centers. The station was in many regards the most important building in town. Residents’ emotional responses toward the loss of local depots could be felt. In Boone County, depots existed in Devon, Kensington, Richwood and Walton—which had both the Southern Railroad and Louisville and Nashville. Campbell County had depots in Bellevue, Brent, California, Dayton, Mentor, Newport, New Richmond and Ross. In Kenton County, there were as many as fourteen.

Southern Depot at Ludlow. Kenton County Public Library.

Both authors grew up in the railroad town of Ludlow, Kentucky, and its depot is a good representation of the many serving the region. As in other communities, the railroad had a tremendous impact on Ludlow. Even though Ludlow was an urban community, it had a rural feel. The railroad hired hundreds of people, and the population of Ludlow grew from 817 in 1870 to 2,469 in 1890. Many of them were Irish and German immigrants who came to work on the railroad. Businesses and industries opened operations to take advantage of the railroad location.19 Today, only a few of the railroad depots exist. Beginning in the 1960s, there was less need for depots. For example, shipments could be transported by other means, such as trucks. The railroads were aggressive at tearing down these historic structures, mainly for economic reasons, such as not paying real estate taxes to local communities. Two that have been saved are in Erlanger and Covington.

Discontinuation of passenger service in Ludlow was announced by the Southern Railroad in 1968. The Ludlow Depot was eventually demolished after almost one hundred years of service. Even now, decades later, current and former residents talk about the old depot, and its emotional bind still exists. This can be said of all railroad communities across Northern Kentucky. These depots hold a special place in the hearts of railroad towns.

BIG BONE SPRINGS HOTEL

The national significance of Big Bone Lick cannot be overstated. It was discovered by Europeans in the early 1700s, and today

Big Bone Lick is a unique state park showcasing the remains of some of America’s most intriguing Ice Age Megafauna. Once covered with swamps, the land that makes up Big Bone Lick featured a combination of odorous minerals and saline water that animals found difficult to resist. For centuries great beasts of the Pleistocene era came to the swampy land in what is now known as Northern Kentucky to feed. Animals that frequented Big Bone Lick included bison, both the ancient and the modern variety; primitive horses, giant mammoths and mastodons, the enormous stag-moose, and the ground sloth. '20

The earliest people can be traced to around 13,000 BC (Pre-Paleo period) to AD 1000 (Late Woodland period). For thousands of years, they hunted the big game that couldn’t resist the mineral and salt springs. The site became an archaeological and paleontological treasure.

According to Hillary Delaney, a researcher and historian with the Boone County Public Library, “The earliest documentation of a business established to cater to tourists in Big Bone dates to about 1815. The ‘Clay House,’ so named for Henry Clay, was positioned near the corner of what are now Beaver Road and Boat Dock Roads–A great spot, easily reached by stagecoach or river vessel.” It began operation in 1815 and was immensely popular. During this time, many people came to the hotel for its health benefits; however, the area also attracted scientists to do research and/or gather bones.

In 1864, Cincinnati grocer Charles McLaughlin bought land at Big Bone with plans for a grand hotel and built a forty-room hotel and several cottages in 1873.

According to Delaney, there are indications “that two to three hotels were operating in the Big Bone Springs area concurrently: the larger Big Bone Springs Hotel and smaller ones.” On May 29, 1869, the Cincinnati Enquirer reported,

[T] here probably never was a season when so many of our citizens have determined to leave the city for a more desirable locality as some of the watering places or at the sea-side shores, and from reports already received, these rural retreats are extensively patronized. The Big Bone Springs, Boone County, Kentucky, are now open for the reception of guests, and we have no hesitation in declaring that no place in the entire country can excel those springs for accommodation and comfort of its guests.

Bathers often frequented the springs for the healing benefits a good soak offered, and they were provided with the privacy and convenience of bathhouses built at near the source of the water.21 At this point in history, the quickest route to the Springs Hotel was on the Ohio River. Generally, guests would arrive at Hamilton, about two miles from the hotel. McLaughlin would arrange transportation to the hotel.

McLaughlin ran the Big Bone Springs Hotel for three years and then went west, turning over management to family and others. According to the Louisville Courier Journal on November 19, 1899, “It was not long after leaving, before the hotel went down, the old-time guests dropped away and the place was closed.” The hotel never reopened. In the 1899 article and interview with McLaughlin, he returned to the springs and lived with his family in one wing of the old hotel. “He is always ready to talk of the old days where things were not as they are now.”

McLaughlin often found bones and amassed quite a collection. He later presented “a valuable collection to the Cincinnati Museum of Natural History.”22