3

SCHOOLS AND CIVIC BUILDINGS

COVINGTON CITY HALL

Many people remember the old Covington City Building that sat at Third and Court Streets at the site of today’s Roebling Suspension Bridge on ramps. Sitting just a couple blocks from the Ohio River, it was a magnificent building and also housed the offices of the Kenton County government. The city and county governments were previously housed in a structure that outgrew its usefulness. Covington and Kenton County were growing and so was the size of the government. The 1843 building was razed in 1899 to make room for a new city hall. During construction, the city made its temporary offices at the Hermes Building, now Molly Malone’s. Dedicated in 1902, the new Covington-Kenton County Building was three stories and had a gable roof lined on each side with a higher tower in the middle. The gabled structure was designed by the architectural firm of Dittoe and Wisenall, which designed many beautiful and historic buildings in Covington, including First Christian Church, the Kentucky Post Building and an addition to Citizens National Bank. The new City Building was composed of brick with a stone foundation and had an archway of stone at the top of entrance steps on Court. It took up the entire block from Court to Greenup and was located on the north side of Third Street. Perhaps the most impressive aspect of the new government building was its appearance as people came across the Suspension Bridge into Covington and saw its beautiful and impressive design. It was the dominant structure upon entering Covington from the bridge.33 The building was razed in 1970.

Covington City Hall and Courthouse, Third and Court Streets, Covington, Kentucky. Kenton County Public Library.

The City Building saw almost seventy years of history and politics of Covington. It was an interesting time, spanning from near the turn of the century to the opening of Riverfront Stadium just across the river and on the other side of the Suspension Bridge. A brochure in 1903 offered tax breaks to companies moving to the city and touted that “Covington also offered cheap coal, good transportation and the best water in America.”34 According to writer Jim Reis, “[B]usinessmen touted Covington as an ideal spot for tobacco factories and warehouses with a base of 7000 union laborers and an excellent streetcar system.” Despite the growth leading to the need for the new city hall, more was to come. Around the time of construction, Covington grew outside its borders. It annexed Peaselburg in 1906 and Latonia and West Covington in 1909. It failed in attempts to annex Ludlow.35 The building served Covington well until its demolition in 1970.

COVINGTON HIGH SCHOOL

Although Covington has had a public school of some type since 1825, the very first public high school was established in 1853. The district organized formally in 1841 when the city council created a board of five citizens to oversee public schools in the city. The next year, the new board started constructing schools.36 Between 1842 and 1852, the first four district schools were built, and by 1925, eleven district schools had been constructed for white elementary school children. In 1872, the beautiful Covington High School building was opened. It was located at Russell and Twelfth Streets and was a twelve-classroom, three-story brick building. It is best described as Victorian Gothic.

The cornerstone was laid on October 25, 1872. By 1880, there were five faculty members and 172 students. According to the bicentennial book Covington, Kentucky: 1815–2015, “The Covington High School was described as having a comprehensive program that offered three graduation courses—a commercial course, a general academic course, and a manual-training course.” Around this time, Covington’s second high school, one for black students, opened. It was named for William Grant, who donated property on Seventh. There were significant differences between the course offerings of the Covington High School and the William Grant High School. Again, according to the Covington bicentennial book, “The William Grant High School was referred to as a standard high school, and the graduates were listed as having received a general degree.”

Covington High School. Kenton County Public Library.

It did not take long for Covington High School to become overcrowded. By 1896, it was beyond capacity. This lasted for over twenty years. In 1915, a bond issue was placed by the school board for funding a new high school building. It failed, and the problem grew worse. In January 1916, another bond issue for $165,000 was placed on the ballot in part because the high school building capacity was 400, with enrollment at 471. By 186 votes, this second bond issue passed.

The cornerstone of a new building was laid on November 27, 1916. Opened in 1919, Holmes High School was located on the Holmesdale property. The school board paid $50,000 for the property from the Holmes estate, which included the Holmes mansion. Daniel Henry Holmes was a wealthy merchant and department store owner from New Orleans. The mansion was better known as the Holmes Castle and stood until 1936, when an administrative building was constructed on the site.

As a result of the opening of Holmes High School, the old building at Russell and Twelfth Streets was left vacant. The school board decided to remodel the old high school building and reopened it in 1919 as a junior high school. They named it John G. Carlisle Junior High School. It served in this capacity until 1937, when a new John G. Carlisle Elementary and Junior High School was constructed.37 The old high school building was then demolished.

HOLMES CASTLE

Daniel Henry Holmes Sr.’s parents died when he was two years old, and he was raised in the Columbia section of Cincinnati by his brother Sam. As a young adult, Holmes went to New York City and worked at the Lord and Taylor Department Store, and when the company opened a new store in New Orleans, Holmes became its manager. Eventually, Holmes bought the store in New Orleans and renamed it the Daniel Holmes Store. He became a very rich man. According to the Encyclopedia of Northern Kentucky, Holmes “purchased all of his merchandise in Europe, where he was known as the ‘King of New Orleans’. By the 1960’s, the Holmes Department Store Chain operated 18 department stores in three states. It was among the largest independent department store chains in the nation.

“Not wanting to keep his family in the hot South in the summer, he built a summer home in Covington, on what is now the Holmes campus. His original estate was called ‘Holmesdale,’ and more or less was bordered by Madison, 25th Street, the Licking River, and Lavassor Avenue. He also had homes in New York City, New Orleans, and Tours, France.”38 It was during or just after the Civil War when Holmes moved his family to Covington. Following the war, he purchased for $200,000 a large Victorian Gothic house and named it Holmesdale. The mansion is better known as Holmes Castle. Upon his purchase of the castle, Holmes hired a Boston firm to create a landscape plan with a pond, pasture and hundreds of trees. A groundskeeper kept cows and sold milk from the property to neighbors.39 Holmes Castle, according to an article published by the Kenton County Library, is likely the most well-known example of lost architecture in Covington “and was designed in the Gothic Revival style, which can be identified by its pointed arch windows and church-like details.” It had sprawling grounds and a lavishly appointed interior. The thirty-two-room estate house was designed after a castle in Siena, Italy.

Holmes Castle, home of Daniel Henry Holmes. Kenton County Public Library.

Holmes died on July 3, 1898, at his apartment in New York City. His body was returned to the Castle for services and was later buried in a family crypt in a suburb of New Orleans. He left the mansion to his son Daniel Jr. The family sold the mansion to the Covington Board of Education for $50,000 in 1919, and it was used as a cafeteria and classrooms for sixteen years but was demolished in 1936. According to the Holmes High School website, “In November of 1936, the senior class was given a tour of the Castle. An auction was held, and anything that could be removed was put up for sale. Any furnishings that remained were taken down to the football field and burned. Over the Thanksgiving holidays, the wreckers moved in, and the Castle was razed.”

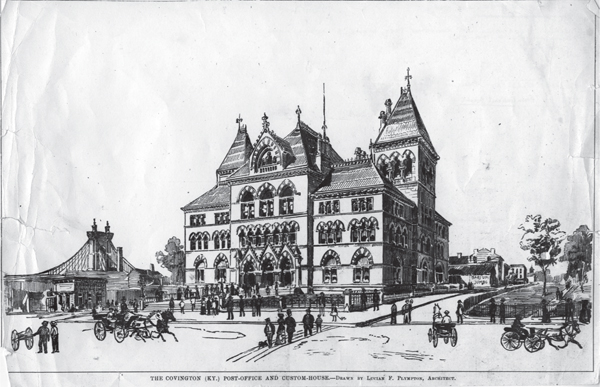

COVINGTON POST OFFICE/FEDERAL BUILDING

Described as an “architectural jewel” of the city of Covington, the U.S. Post Office and Federal Building was a large Victorian Gothic structure. It stood at the southeast corner of Third and Scott Streets. Even before the Civil War, a federal building/post office was considered for the city of Covington. In the early 1870s, the U.S. government allocated $250,000 for the project. The project started when the Treasury Department purchased a 167-foot by 150-foot lot for $30,660.55–the Third and Scott Street site. According to the Kenton County Public Library webpage and research, “The building was designed by William Appleton Potter, Supervising Architect of the United States Treasury Department. The 3-story structure was built of native limestone on 3’ thick foundations. The exterior was decorated with intricate stone carvings and an ornate mansard roof. The interior included woodwork of ash, fruitwood and oak; marble columns and detailed molded plaster friezes in the courtrooms. The cornerstone of the building was set in place on July 4, 1876, the centennial of the Declaration of Independence. Total cost of the structure amounted to $264,231.01”40 Potter was known for his design of many structures at Princeton University and municipal buildings, and he served as supervising architect of the U.S. Treasury. The Richardsonian Romanesque style is identified by “heavy stone masonry, lots of arches, and decorative belt course banding between floors.”41

Covington Federal Building, “an architectural jewel.” Kenton County Public Library.

During its time of service, the federal building housed the Covington Post Office and the federal courts. In 1946, the building was abandoned by the federal government when a new structure was constructed on Scott Street and Seventh Avenue. The old federal building was sold to Kenton County for $15,000 and eventually became home to the Kenton County Vocational School. The school left the building on June 5, 1962, to move into a new facility. The county used the old federal building for storage until 1968, when it was demolished. On its site, Kenton County built a new government building for its operations. The high-rise building sits at the foot of the Roebling Suspension Bridge and houses the administrative office of the county. Until a new corrections facility was built, the county jail was located on the upper floors.

In August 1999, a new federal courthouse opened on Fifth Street. It was constructed for $22 million and came in $1 million under budget. The Scott Street federal building (the second federal building) was given entirely to the postal service, which still operates out of the facility.

SPEERS MEMORIAL HOSPITAL

Elizabeth L. Speers was a wealthy resident of Dayton, Kentucky. She and her husband, Charles, settled in Dayton in 1883. Unfortunately, Charles died that same year. When she died in 1894, Elizabeth gave $100,000 to build a hospital in Dayton named after her late husband. The family money was made by Charles selling cotton during the Civil War. In accordance with the will, a circuit court judge appointed trustees for the new hospital, and they met for the first time on July 6, 1895. Construction of the hospital was begun in October 1895, and in 1897, the facility admitted its first patient. In the beginning, the hospital had thirty private rooms and four wards. In 1911, an east wing was built, adding another ward and seven more private rooms.42 The additional ward was for children.

Speers Hospital was built at a large block of Main and Boone Streets and Fourth and Fifth Avenues. The total cost was $75,000, and Elizabeth Speers’s donation provided for construction and equipment purchases. It did not provide for operating costs, which included thirty-one doctors, many of them quite prominent for the area.43 A nurse training program was started in 1901, and three years later, the first class of seven women graduated. The ceremony was held at the Dayton High School auditorium. Other major developments in Speers Hospital’s history include a deal with the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad in 1912 to care for employees and the construction in 1937 of a residence for student nurses. Speers became known as “a railroad hospital.” By the time of the great flood of 1937, the hospital had one hundred beds, five wards and thirty-eight patient rooms.

However, in 1937, the flood caused devastation not only to the hospital but to the entire region as well. Patients were removed to the Dayton High School and other facilities in Bellevue and Newport. Floodwaters made it into the first floor, ruining equipment and resulting in major damage. The Campbell County Chamber of Commerce led a fundraising campaign to help the hospital. According to the Encyclopedia of Northern Kentucky, “In 1938 a number of prominent physicians lectured at the hospital. The speakers included the world-renowned brain surgeon Dr. Frank Mayfield and the developer of the first live polio vaccine Dr. Albert Sabin.” Speers Hospital ran into problems in the years following the flood. The new equipment aged, and the facility was in need of modernization. The funds were not available. In many ways, public support for the hospital began to wane, and many questioned its existence. By the late 1940s, doctors grew even more concerned about the Speers facility and discussed the need for a new hospital. Seven doctors led efforts for a $1 million bond issue for a new hospital. The issue was approved by the voters, and a new modern hospital was constructed in 1954–St. Luke Hospital. It was located in Fort Thomas and today still stands as St. Elizabeth Hospital. Speers actually survived for many more years and ceased operations in 1973 after being purchased by St. Elizabeth Hospital of Covington. Speers Hospital sat vacant for six years and was demolished in 1979. Senior citizen housing was built on the site approximately four years later.

Speers Memorial Hospital, Dayton, Kentucky. Kenton County Public Library.

FORT THOMAS MILITARY RESERVATION

The military barracks of Newport were covered heavily by water in the great floods of 1884 and 1887. As a result, it was decided to move the barracks to a new reservation in Fort Thomas that offered higher grounds, fresh water, train transportation for materials and accessibility by streetcar to the urban core of Cincinnati, Newport and Covington. The Kentucky General Assembly ceded that land to the federal government for the military reservation, which was dedicated on June 29, 1890. Congress appropriated $3.5 million for construction, and it began quickly. First named Fort Crook, the establishment was later renamed by Army Chief of Staff General Phillip Sheridan to honor General George Henry Thomas. Thomas was known as the “Rock of Chickamauga.” The Battle of Chickamauga and Thomas’s defeat of Confederate general John Bell Hood in 1864 was a decisive battle in the Civil War.

Fort Thomas military barracks. Kenton County Public Library.

The first buildings at the fort were funded by Congress in 1887. The first commanding officer was Colonel Melville A. Cochran, and the first troops arrived in 1890. These troops, the Sixth Infantry, started what would be a military operation until the 1960s. Over thirty buildings would eventually be built at the fort. The water tower, which became the symbol of the fort and the city, was constructed in 1889–92.44 It was the sixteenth structure built at the fort and spans 102 feet. Enclosed within its walls was a standpipe with a capacity of 100,000 gallons. It was constructed at a cost of $10,995. In 1891, the mess hall was finished at a cost of $20,407 and today serves as a beautiful community center. One of the most famous Fort Thomas troop assignments started in April 1898 with the outbreak of the Spanish-American War. The Sixth Regiment joined the rest of the army in Tampa, Florida, and left for Cuba and participated in the Battle of San Juan Hill. During this time, the barracks were used as a temporary hospital, and the army regiments stayed in tents on the property.

During the twentieth century, the fort stayed in use but was more limited. During World War I, the fort was a recruit center, and seventy thousand men passed through. Twenty temporary buildings were constructed. In 1922, the Tenth Infantry arrived and remained at the complex until 1940. The unit was called upon to do community service at various times, especially during the Great Depression.

The fort served as an induction center during World War II. Paul Tibbets was inducted at Fort Thomas as a flying cadet–Tibbets was the pilot who dropped the first atomic bomb in August 1945. According to the Campbell County Historical Society, three thousand men passed through the fort per week. It served in this capacity until the end of the war in 1945. A rehabilitation center was opened in 1944 by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Starting in the 1960s, the Department of Defense began to dispose of the fort, and in 1964, the last soldier went through the induction center. The facility became a nursing home operated by the Department of Veterans Affairs in 1967. In 1972, the land was subdivided and sold. Land was also transferred to the City of Fort Thomas for what is now called Tower Park.

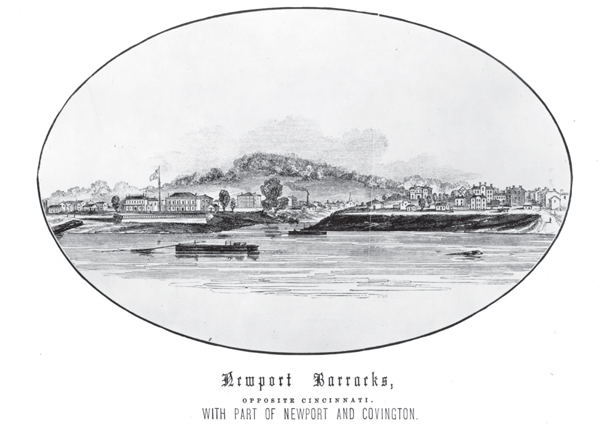

NEWPORT BARRACKS

Fort Washington in Cincinnati was the first military post in the Greater Cincinnati area and was built around 1789. Several things changed in a short time frame. Indians were no longer much of a threat to the region, and the land Fort Washington sat on (Third and Broadway) in downtown Cincinnati had become quite valuable. Across the river was an opportunity with two things going for it. First, the land was a good location, right on the conflux of the Ohio and Licking Rivers. Second, moving the fort to Newport had a big supporter–General James Taylor, one of the richest and most influential individuals in Kentucky. Not only was he the founder of Newport, he was the cousin of two future presidents, Madison and Taylor, as well. It was decided to move the fort and establish the Newport Barracks. In 1803, on approximately four acres, the Newport Barracks was established. The land was bought for one dollar from the Taylor family, but an additional two acres were purchased in 1806 because the original purchase proved to be too small. This time the acres were bought for forty-seven dollars each, and people questioned why such a high price was paid.45 In 1848, the City of Newport gave additional land to the government. General Taylor was chosen to oversee construction of the barracks and, according to the federal government, was charged with constructing three buildings: a two-story arsenal, barracks and a circular brick powder magazine.

The first group of soldiers to occupy the barracks as a permanent garrison did so in July 1806. Steve Preston described some early action in an article titled “Our Rich History: When the Army Came to Newport”:

[A]s the United States began its second war with England, the War of 1812, the Newport Barracks became the major supply and mobilization point for the Western Theater. Although war materiel was hard to come by, much of what was available came through Newport on its way to troops fighting in Northern Ohio and near Detroit. Units such as the 4th Regiment, 7th Regiment, 17th Regiment and nearly all Kentucky Militia units passed through Newport. During the Mexican American War, the Newport Barracks was heavily utilized. Its location on the Ohio River provided rapid deployment for troops heading to the Mississippi River and Louisiana, and thence to Mexico. The Barracks was at its peak as it sent recruits to Louisiana, soon after Mexico broke off diplomatic relations with the United States in 1845.

Newport Barracks. Kenton County Public Library.

In 1814, the barracks held approximately four to six hundred prisoners of war, most from General William Henry Harrison’s victory at Moravian Town in 1813.

During the Civil War, the Newport Barracks was a Union post. It served as a prisoner-of-war camp and hospital. The downfall of the fort resulted from neglect after the Civil War, and its fate was sealed by the great floods of the 1800s. In fact, it was flooded three straight years: 1882, 1883 and 1884. The Newport Barracks covered in water prompted the federal government to move to Fort Thomas. In 1887, it was recommended that the barracks be abandoned, and General-in-Chief Phillip Sheridan agreed. In 1896, after some debate, the City of Newport accepted the return of the property. Today, the site of the Newport Barracks is the General James Taylor Park, located on the Licking and Ohio Rivers.

BOONE COUNTY COURTHOUSE,1817

The old courthouse currently standing in Burlington is in reality the third courthouse built on the corner of Washington and Jefferson Streets. Between the years of 1799 and 1801, county functions were conducted in homes until the first courthouse was constructed. The 1801 courthouse was made of logs. It had only served as the official courthouse for around sixteen years when it was replaced with a larger two-story brick building in 1817. In addition to the courthouse, in 1817, several other notable occurrences took place, including the Anderson Ferry carrying its first goods across the Ohio River, the Benjamin Piatt Fowler House being built near Union and the Petersburg Mill incorporating.

The 1817 courthouse was remodeled several times and eventually replaced in 1889 when a new one was built. The 1889 courthouse still stands on the site of the two previous buildings and was renovated in 2017. It was named the Ferguson Community Center in 2018.

THE MORGAN ACADEMY

Very few people in Northern Kentucky are aware of the Morgan Academy of Burlington. Long lost to history, the academy was a private school, as were most early schools of Northern Kentucky. Originally known as the Boone Academy, it was an important learning institution in Boone County. Established in 1814, it was funded by the sale of seminary lands set aside by the Commonwealth of Kentucky following its entry into the United States. It had various names throughout the years, including Boone Academy (1814–32), Burlington Academy (1833–41) and Morgan Academy (1842– 97). According to the Encyclopedia of Northern Kentucky, “By 1842 the new name, Morgan Academy, had been cut in stone and etched in gold leaf on the front of the Academy’s building.”

Allen Morgan, a Boone County resident, died without a will or heirs, and under Kentucky law, estates in this situation had to be donated for educational purposes. The Morgan Academy adopted his name after inheriting his estate. Tuition near the end of its operation was $1.50 per month for primary students, $2.50 for intermediate students, $4.00 for high school. Room and board was an additional $2.50 to $3.50 per week.46 County leaders who attended Morgan Academy include J.W. Calvert, Dr. Otto Crisler, J.W. and Fountain Riddell and Dr. Elijah Ryle.

In 1835, a Lawrenceburg, Indiana newspaper reported an order of the Morgan Academy Board of Trustees that “teachers are wanted to conduct the male and female departments of the above Institution, as both the teachers now engaged in said school will leave at the end of the present session. No teacher need apply whose moral character is not unexceptional, and who cannot come well-recommended, as it regards qualifications, to teach a respectable Academy. The next session will commence on the first Monday in October ensuing.”47 In 1840, the academy had sixty students and a $5,000 endowment.48

Morgan Academy closed in 1897, just ahead of school reform in Kentucky that changed the landscape. According to Margaret Warminski, writing for the website Chronicles of Boone County by the Boone County Public Library,

A series of reforms enacted by the Kentucky legislature beginning in 1908 revolutionized education and raised standards. In the wake of these changes, local school districts began to consolidate into larger entities serving wider geographical areas, and one- and two-room schools were replaced by new buildings. Throughout the county new buildings were constructed housing grades one through twelve under one roof, with primary and secondary classes on separate floors. High schools also were established in Burlington,

Union, Walton and Verona. The next major building campaign took place in the 1930s, as graded schools of conspicuously modern design were built in Florence, in Burlington and on U.S. 42 south of Union.

The Morgan Academy building was located next to the Old Burlington Cemetery and shared a fence with the burial ground. It was a two-story red brick colonial building “well-constructed with two class rooms below and an assembly hall on the second floor. The front entrance opened into a hall from which a stairway led to the second floor where dances and town meetings were held. (In the) back of the hall was a large class room. (In) back of this was another hallway with an outside door at either end and another door opening into another large classroom at the back.”49 Today, the site is an empty lot.