AS THE APO FOUNDERED, THE majority of those to the left of the SPD remained committed to legal, aboveground activism. Nevertheless, a section of the movement had begun testing the waters with another kind of praxis, and for the purposes of our study, it is to this that we will now turn.

The first experiments with armed struggle developed out of the counterculture, as individuals around the K.1 commune in West Berlin began carrying out firebombings and bank robberies. Coming from a milieu where drugs and anarchism mingled freely, these young radicals hung out in a scene known as “the Blues,” and would take on the purposefully ironic name of the “Central Committee of the Roaming Hash Rebels.” As Bommi Baumann later explained, with perhaps a tongue in his cheek:

Mao provided our theoretical basis: “On the Mentality of Roaming Bands of Rebels.” From the so-called robber-bands, he and Chu-Teh had created the first cadre of the Red Army. We took our direction from that. We directed our agitation to make the dopers, who were still partly unpolitical, conscious of their situation. What we did was mass work.4

The Hash Rebels carried out actions under a number of different names, but became best known as the Tupamaros-West Berlin, after the urban guerillas in Uruguay.1 Initially, this antiauthoritarian, pre-guerilla tendency suffered from anti-intellectualism, unquestioned male chauvinism, and a lack of any coherent strategy. It has also been criticized for tolerating and engaging in antisemitism under cover of anti-Zionism, one of its first actions being to firebomb a cultural centre housed in a synagogue on the anniversary of a Nazi pogrom.2

On the other hand, it did seem to enjoy an organic relationship with its base, such as that was.

As the APO fell apart and many of the Hash Rebels’ leading members were arrested or simply had a change of heart, what remained of this tendency would crystallize into a guerilla group known as the 2nd of June Movement (2JM—a reference to the date when Benno Ohnesorg had been killed in 1967). Rooted in West Berlin, this group eventually overcame many of its initial weaknesses while retaining an accessible and often humorous rhetorical style that resonated with many in the anarchist and sponti scenes throughout the country.

The second guerilla tendency, with which we are more directly concerned, brought together individuals who were peripheral to the countercultural milieu of the Hash Rebels, and of a somewhat more serious bent. As Bommi Baumann would later explain, they “formed at about the same time as we did, because they considered us totally crazy.”3 This second tendency was much more theoretically rigorous (or pretentious, to its critics), and heavily influenced not only by Marx, Lenin, and Mao, but also by New Left philosophers ranging from Nicos Poulantzas to the Frankfurt School.

This nascent Marxist-Leninist guerilla scene had its earliest manifestation in the firebombing of two Frankfurt department stores on April 3, 1968, one week before Rudi Dutschke was shot. Petrol bombs with rudimentary timing devices were left in both the Kaufhaus Schneider and Kaufhof buildings, bursting into flames just before midnight. The fires caused almost 700,000 DM ($224,000 U.S.) in damage, though nobody was hurt.

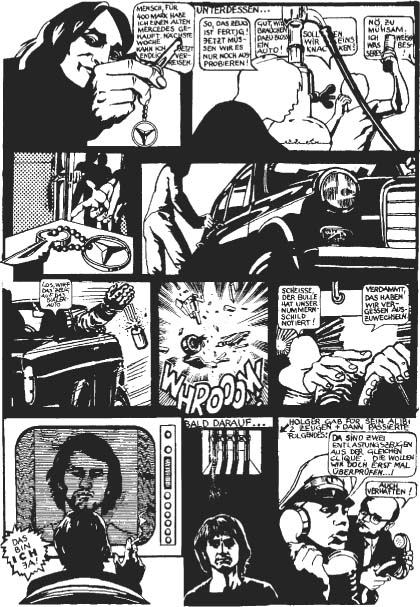

A cartoon from the radical counterculture magazine Agit 883 shows a young man bearing a striking resemblence to Holger Meins (who was a member of the newspaper’s editorial collective) throwing an incendiary device of some sort out of a car. He gets busted because he forgot to change the car’s license plates, but luckily some of his friends are willing to vouch for him and the police are forced to release him, even though they know he did it.

On April 5, Horst Söhnlein, Thorwald Proll, Gudrun Ensslin, and Andreas Baader, who had all traveled from West Berlin to carry out the action while attending an SDS conference, were arrested and charged with arson.

The four had taken few precautions to protect their identities and avoid arrest. They had issued no communiqué, and in retrospect, the action appears almost flippant in its execution. Indeed, some of those arrested initially denied their participation, and later tried to minimize it all, Baader claiming, “We had no intention of endangering human life or even starting a real fire.”1

In court, the four had no united strategy; apparently without bitterness or recrimination, Baader and Ensslin at first tried to present a legal defense, and then switched to accepting full responsibility while insisting that Proll and Söhnlein were both completely innocent.2 For their part, these two did not deny their involvement, yet chose not to defend themselves, though Proll did offer an eloquent denunciation of the court and judicial system (see pages 66-78).

In the end, there was no denying that this was a political action, albeit an ill-defined one. In court, Ensslin explained that that the arson was “in protest against people’s indifference to the murder of the Vietnamese,” adding that “We have found that words are useless without action.”3

Then, in a statement that could only be appreciated in retrospect, she told a television reporter, “We have said clearly enough that we did thewrong thing. But there’s no reason for us to discuss it with the law or the state. We must discuss it with people who think as we do.”4

While the four were repudiated by the SDS, they were embraced by others for whom the step into illegality seemed both appropriate and timely. “They were like little media stars for the radical left,” Thorwald’s younger sister Astrid Proll would recall years later.5

One of these admirers was Ulrike Meinhof, who had divorced konkret publisher Klaus Rainer Röhl and moved to West Berlin with their twin daughters in 1967. Meinhof visited Ensslin in prison, and would approvingly write about the case in her magazine column. “[T]he progressive moment of arson in a department store does not lie in the destruction of goods,” she opined, “but in the criminality of the act, the breaking of the law…”6

Publicly, the arsonists’ friends from the K.1 commune declared their solidarity, Fritz Teufel paraphrasing Bertolt Brecht to the effect that “It’s always better to torch a department store than to run one.”7 Privately, however, they wondered at how clumsily the whole thing had been carried out, some even supposing that the four might suffer from some “psychic failure,” a subconscious desire to go to jail.8

In October 1968, the four were each sentenced to three years in prison.

As the judge read out the verdict a familiar figure stood up: “This trial belongs before a student court,” Daniel Cohn-Bendit9 shouted, at which point the gallery erupted into pandemonium, spectators swarming the guards as two of the accused attempted to make a break for it. Three people, including Cohn-Bendit, were arrested as a result of this melee, and all four young arsonists remained in custody.10

The next day, persons unknown lobbed three molotov cocktails into the Frankfurt courthouse.11 Again, no one was hurt.

The arsonists had been represented by Horst Mahler, whom the state failed to have disbarred just days after this defeat, in the hearings which would provoke the aforementioned Battle of Tegeler Weg. The four would not be able to participate in that historic rout of the West Berlin police: despite appealing their sentence, they remained imprisoned until June of 1969. Only then were they finally released on their own recognizance until such a time as the court finally reached its decision.

As the summer of 69 turned to fall and the court continued to deliberate, the newly released Ensslin, Baader, and Proll would busy themselves working in the “apprentices’ collectives” scene. These collectives consisted of young runaways from state homes, and were at the time the object of political campaigning from the disintegrating APO. As Astrid Proll would recall:

When Andreas Baader and Gudrun Ensslin were released from custody they knew exactly what they wanted. Unlike the drugged “communards” they radiated great clarity and resolve… Gudrun and Andreas launched a big campaign in Frankfurt against the authoritarian regimes in young offender institutions. We lived with youths who had escaped from closed institutions, joined them in fighting for their rights, and managed to achieve some successes. Ulrike Meinhof, as a commited (sic), critical journalist, joined us and became friends with Gudrun and Andreas.1

In November 1969, the court denied their appeal and ordered the four back to prison: only Söhnlein turned himself in. Ensslin and Baader went underground and set about establishing the contacts that would be necessary for a prolonged campaign of armed struggle. Thorwald Proll was soon abandoned—he was not considered serious enough—but his sister Astrid joined them.

Over the next months, the fugitives would cross into France and Italy and back to West Berlin again, laying the groundwork for the future organization. At this point, they resumed contact with their lawyer Horst Mahler,2 who was still facing criminal charges stemming from the April 1968 revolt.3 While enduring these legal battles, Mahler had himself been trying to set up a “militant group” in Berlin,4 and so joining forces with his former clients simply seemed like a wise strategic decision.

At the same time, the serious Marxist-Leninists considered—and rejected—the idea of joining forces with the anarchist guerilla groups that were coalescing within the Roaming Hash Rebels scene. The reasons for this decision to continue following separate paths are not clear-cut, and the consequences were more nuanced than might be expected. It is important to remember that many of the figures involved knew each other from the APO, in some cases were friends, and certainly would have had opinions about each other’s politics and personalities. It has been said that Dieter Kunzelmann, a prominent figure in the Hash Rebels scene, was wary of Baader claiming leadership.5 It has also been suggested that the RAF as a whole had a haughty manner, and was made up of middle-class students who didn’t fit in with the supposedly more proletarian 2JM.6

While none of the guerillas have ever said as much, one cannot help but wonder what RAF members might have thought of the countercultural scene out of which the Hash Rebels had developed, specifically the sexual arrangements. The K.1 commune was not only famous for its brilliant agit prop, its radical cultural experiments, and its phenomenal drug consumption, but also for its iconic role in the sexual revolution which swept the Federal Republic in the years of the APO. At the same time as K.1’s sexual politics constituted a reaction to the oppressive conservatism of Christian Germany, it was also very much a macho scene built around the desires of key men involved. Polygamy was almost mandatory, and women were passed around between the “revolutionaries”—as one male communard put it, “It’s like training a horse; one guy has to break her in, then she’s available for everyone.”7 As Bommi Baumann would later admit regarding the Hash Rebels, “They were just pure oppressors of women; it can’t be put any other way.”8

There were always many women playing central roles in the RAF. It is difficult to imagine Ulrike Meinhof, Gudrun Ensslin, or Astrid Proll putting up with the kind of sexist libertinage which has been documented in the West Berlin anarchist scene. Indeed, during her own period in the wild depths of the counterculture, Proll had not gone to K.1 but had chosen to live in a women’s only commune, helping to form a short-lived female version of the Hash Rebels, the Militant Black Panther Aunties.9

These various explanations, however, are not only difficult to evaluate, they also risk obscuring the fact that cooperation between the anarchist guerilla scene and the Marxist-Leninists would continue throughout the seventies, many members of the former eventually joining the RAF, while a few individuals continued to carry out operations with both organizations. Certainly, from what can be seen, a high level of coordination and solidarity existed between the groups at all times. While their supporters might occasionally engage in unpleasant disputes, the actual fighters seem to have maintained good relations even as they traveled their different roads.

Ultimately, in the early 80s, the 2nd of June Movement would publicly announce that it was joining the RAF en masse. This provided the opportunity for some 2JM political prisoners who opposed the merger to give their own explanation as to why they had always chosen to fight separately. Although these observations were made over ten years later, they help shed light on relations in these early days:

The contradiction between the RAF and the 2nd of June at that time was the result of the different ways the groups had evolved: the 2nd of June Movement out of their members’ social scene and the RAF on the basis of their theoretical revolutionary model. And, equally, as a result of the RAF’s centralized organizational model on the one hand, and our autonomous, decentralized structures on the other. Another point of conflict was to be found in the question of the cadre going underground, which the RAF insisted on as a point of principle.

As such, the immediate forerunners to the 2nd of June Movement were always open to a practical—proletarian—alternative; an alternative that had nothing to do with competition, but more to do with different visions of the revolutionary struggle.

There was strong mutual support and common actions in the early period of both groups… At the time both groups proceeded with the idea that the future would determine which political vision would prove effective in the long run.1

So, during this germinal period, friendly contacts were maintained even as differences were clarified between the various activists who were choosing to take the next step in the struggle.

For shelter and support, those who were underground became dependent on the goodwill and loyalty of friends and allies who maintained a legal existence. One of those who occasionally sheltered Baader and Ensslin was Ulrike Meinhof, who was already feeling that their commitment and sense of purpose contrasted sharply with what she experienced as her own increasingly hollow existence as a middle class media star, albeit one with “notorious” left-wing politics. At the same time, Meinhof continued to work with young people in closed institutions, specifically girls in reform school, with whom she began producing a television docudrama.

While Meinhof eventually became world famous for what she did next in life, it is worth emphasizing that her time as a journalist was far from insignificant. As her biographer Jutta Ditfurth has argued:

With her columns, and above all with the radio features about things like industrial labor and reform school children, Meinhof had an enormous influence on the thinking of many people. Much more than she realized. She took on themes that only exploded into view years later. For instance, the women’s question. When women in the SDS defended themselves from macho guys, they did it with words and sentences from Meinhof’s articles. She could formulate things succinctly.2

Baader was captured in West Berlin on April 3, 1970, set up by a police informant.3 Peter Urbach had been active around the commune scene for years, all the while secretly acting on behalf of the state. He was particularly “close” to the K.1 commune, and had known Baader since at least 1967. While the bombs and guns Urbach supplied to young rebels never seemed to work, the hard drugs he provided did their job nicely, showing that even as theories of the “liberating” effects of narcotics were being touted in the scene, the state knew on which side its bread was buttered.4

While it has always been stressed that there were neither hierarchies nor favorites amongst the various combatants, Baader seemed to bring with him a sense of daring and possibility which would always make him first amongst equals, for better or for worse. As such, following his capture, all attention was focused on how he could be freed from the state’s clutches.von Seckendorff

A plan was hatched, whereby Meinhof would use her press credentials to apply for permission to work with Baader on a book about youth centers, an area in which by now they both had some experience. The prison authorities reluctantly agreed, and on May 14 Baader was escorted under guard to meet her at the Institute for Social Issues Library in the West Berlin suburbs.

This provided the necessary opportunity. Once Baader and Meinhof were in the library, two young women entered the building: Irene Goergens, a teenager who Meinhof had recruited from her work with reform school kids, and Ingrid Schubert, a radical doctor from the West Berlin scene. They were followed by a masked and armed Gudrun Ensslin, and an armed man. Drawing their weapons, these rescuers moved to free Baader. When an elderly librarian, Georg Linke, attempted to intervene, he was shot in his liver.1 The guards drew their weapons and opened fire, missing everyone, and all six jumped out of the library window and into the getaway car waiting on the street below.2

Barely a month after his arrest, Baader was once again free.

The library breakout made headlines around the world, both Meinhof and Ensslin being identified as likely participants. Journalists tried to outdo each other in their sensationalist tripe, describing the one as a middle class poseur and the other as a former porn actress.3 Headlines continued to be made when a neofascist arms dealer, Günther Voigt, was arrested and charged with selling the guerilla their guns.4 Then, French journalist Michele Ray declared that she had met with Mahler, Meinhof, Ensslin, and Baader in West Berlin—she promptly sold the extensive interviews she had taped to Spiegel.5

The group had made an impression. Its first action had struck a chord. Yet this was very much a mixed blessing, as Astrid Proll, who had driven the getaway car during the jailbreak,6 would later explain:

I think we were all very nervous; I remember some people throwing up. Because we weren’t so wonderful criminals, we weren’t so wonderful with the guns, we sort of involved a socalled criminal who could do it so much better than we, and… he was so nervous that he shot somebody. He didn’t kill him, but he shot him very very badly, and that was really really very bad for the whole start of it.7

As she elaborated elsewhere:

After a man had been severely hurt… we found ourselves on wanted lists. It was an accident that accelerated the development of the underground life of the group. Ulrike Meinhof, who had so far been at the fringes of the group, was all of a sudden wanted on every single billpost for attempted murder against a reward of DM 10,000… When we were underground there were no more discussions, there was only action.8

In what would be a recurrent phenomenon, the state made use of the media frenzy around the prison-break to help push through new repressive legislation—in this case the so-called “Hand Grenade Law,” by which West Berlin police were equipped with hand grenades, semiautomatic revolvers, and submachine guns.9

This was all hotly debated on the left, prompting the fugitives to send a letter to the radical newspaper 883, in which they explained (somewhat defensively) the action and their future plans. At the insistence of the radical former film student Holger Meins who was working at 883 at the time and who would later himself become a leading figure in the RAF, the newspaper published the statement, making it the first public document from the guerilla. (Even without Meins’ support, it would have been odd for 883 to not publish the text: Baader, Meinhof, Mahler, and Ensslin had all formerly served in the editorial collective, as had several other individuals who would go on to join the guerilla.)1

The Red Army Faction had been born.

The next year was spent acquiring technical skills, including a trip to Jordan where more than a dozen of the aspiring German guerillas received training from the PLO. While this first trip may not have had great significance for the group, given the subsequent importance of its connection with certain Palestinian organizations, it may be useful to examine the context in which it occurred.

At the time, Jordan contained a very large Palestinian refugee population, one which had swollen since the 1967 Israeli Occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip; by 1970, the Palestinians constituted roughly 1,000,000 of the country’s total population of 2,299,000.

Based in the refugee camps, the PLO managed to constitute itself as a virtual parallel state within the country. Indeed, many considered that revolution in Jordan could be one step towards the defeat of Israel, an idea expressed by the slogan, “The road to Tel Aviv lies through Amman”—a sentiment which worried King Hussein, to say the least—as did the increasing use of Jordanian territory as a rear base area for all manner of Palestinian radical organizations.2

In September 1970, the left-wing Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine skyjacked three western aircraft, landing them in Dawson’s Field, a remote desert airstrip in Jordan. This provided Hussein with the excuse he needed, and the PLO soon came under attack from the monarch’s armed forces, supported by Israel. By the time a truce was brokered, between 4,000 and 10,000—Yassir Arafat would claim as many as 20,000—Palestinians had been killed, including many noncombatants. (This would be remembered as “Black September,” and it was in memory of this massacre that the PLO’s unofficial guerilla wing would adopt that name.)

Prior to this, the Palestinians’ Jordanian bases were important sources of inspiration and education for revolutionaries, not only in the Arab world, but also in many European countries. While the largest number of visitors came from Turkey3—many of whom would stay and fight alongside the Palestinians—there were also Maoists, socialists, and aspiring guerillas from France, Denmark, Sweden, and, of course, West Germany. (It would be claimed that members of the Roaming Hash Rebels scene had already received training from the Palestinians, and Baumann has pointed to this as a turning point in its transformation into a guerilla underground.)4

Even during their Middle Eastern sojourn, the RAF continued to make headlines in Germany, Horst Mahler sending a photo of himself waving a gun and dressed like a fedayeen to a radical newspaper with the message, “Best wishes to your readers from the land of A Thousand and One Nights!”5

Juvenile theatrics aside, this trip signaled the very public beginning of an aspect of the RAF which would bedevil the police, namely, their proficient use of foreign countries as rear base areas. As has been discussed elsewhere:

Rear base areas are little discussed, but essential to guerillas. This is something precise: a large area or territory, bordering on the main battle zone, where the other side cannot freely operate. Either for reasons of remoteness or impenetrable mountain ranges, or because it crosses political boundaries.6

The RAF would make extensive use of various Arab countries as rear base areas throughout their existence, places where one could go not only to train, but also to hide when Europe got too “hot.” During the 1970s at least, it does not seem to have been the governments of these countries which provided the group with aid and succor, but rather various revolutionary Palestinian organizations which were deeply rooted in the refugee populations throughout the region. In this way, in the years following the Palestinians’ defeat at the hands of Jordan’s armed forces in 1970, Lebanon and the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen emerged as homes away from home for more than one West German revolutionary.

Another source of foreign support, of course, was the “communist” German Democratic Republic—East Germany—from which the RAF and other guerilla groups would receive various forms of assistance over the years. As far as the RAF is concerned, it is unclear exactly how or when this relationship began. Certainly if it existed in the early seventies, this was very secret, and indeed unimagined on the radical left, for which the “other” German state remained a corrupt and authoritarian regime, alternately “Stalinist” or “revisionist,” but in any case one from which little good could come.

And yet it is known that, as early as 1970, the GDR did choose to knowingly allow the guerilla to pass through its territory, for instance on flights to and from the Middle East. After the first trip to Jordan, it even detained one member—Hans-Jürgen Bäcker—and questioned him about the underground for twenty-four hours, but then released him.1 Clearly, by the end of the decade, this policy had been extended to provide other sorts of assistance. It has also been claimed that even at the time of the 1970 training expedition, there were plans to relocate Meinhof’s twin daughters to East Germany if their father won custody away from her sister.2

Given the unpopularity of the GDR, why was this aid accepted, and what effects did it have on the RAF?

The answer to the first of these questions is easy enough to guess: at first, East German “aid” seems to have been very limited in scope, really little more than turning a blind eye to what was going on.3 Who could complain about that?

Eventually, as we will see, more substantial favors would be forthcoming: shelter, training, even new identities—and yet, for most of its history, there is absolutely no indication that the RAF was choosing its targets or formulating its ideology to please foreign patrons. This would become more debatable near the end, but certainly in the 1970s, the RAF - Stasi connection seems to have been casual if not ephemeral.

At most, one might perhaps argue a case of the GDR egging the guerilla on as a way to get at the Americans, in the context of the ongoing conflagration in Vietnam.

Certainly, throughout the 1970s, the Palestinian connection was of far greater importance, and yet the guerilla’s first visit to the Middle East ended on an unpromising note: according to several reports, the West Germans were far from ideal guests, and the Palestinians eventually sent them on their way.

They returned to West Berlin—via the GDR—as the summer of 1970 came to an end.4

The group now set about obtaining cars and locating safehouses. New contacts were made, and new members were recruited, among them Ilse Stachowiak, Ali Jansen, Uli Scholze, Beate Sturm, Holger Meins, and Jan-Carl Raspe, this last being an old friend of Meinhof’s, and himself a founding member of Kommune 2.5 Some of these individuals would soon think better of their decision and drop out at the first opportunity, others would determine the very course of the RAF, and in some cases give their lives in the struggle.

But first, the young guerilla needed to acquire funds, and to this end a daring combination of bank raids was planned in cooperation with members of the Roaming Hash Rebels scene.6 Within ten minutes, on September 29, three different West Berlin banks were hit: the revolutionaries managed to make off with over 220,000 DM (just over $60,000) without firing a shot or suffering a single arrest.7 As Horst Mahler’s former legal assistant Monika Berberich, who had herself joined the RAF, would later explain, “It was not about redistributing wealth, it was about getting money, and we weren’t going to mug grannies in the streets.”8

The “triple coup” was a smashing success. Things were looking good.

Then, on October 8, police received an anonymous tip about two safehouses in West Berlin: Mahler and Berberich, as well as Ingrid Schubert, Irene Goergens, and Brigitte Asdonk, were all arrested. (It was suspected that Hans-Jürgen Bäcker had snitched to the police. He was confronted and denied the charge, but quickly parted ways with the guerilla. The fact that he was left unmolested should be taken into account when evaluating later claims that the RAF executed suspected traitors or those who wished to leave its ranks.)1

Following these arrests, the RAF moved to transfer operations outside of West Berlin, and members of the group began crossing over into West Germany proper. During this period, the fledgling guerilla burglarized the town halls of two small towns, taking blank ID cards, passports, and official stamps for use in future operations.

On December 20, Karl-Heinz Ruhland and RAF members Ali Jansen and Beate Sturm were stopped by police in Oberhausen. Ruhland, who was only peripheral to the group, surrendered while Jansen and Sturm made their getaway. The next day Jansen was arrested along with RAF member Uli Scholze while trying to steal a Mercedes-Benz. (Sturm soon left the guerilla, as did Scholze when he was released one day after his capture. Ruhland cooperated with police, helping to reveal the location of safehouses and testifying in court against RAF members. Jansen received a ten year sentence for shooting at police.)

On February 10, 1971, Astrid Proll was spotted by Frankfurt police along with fellow RAF member Manfred Grashof. The police opened fire in a clear attempt to kill the two as they fled; luckily, they missed. Subsequently, the cops involved would claim that they had shot in selfdefense, yet unbeknownst to them the entire scene had been observed by the Verfassungsschutz, who filed a report detailing how neither of the guerillas had even drawn their weapons. This fact would remain suppressed by the state for years.2

The alleged “firefight” with Proll and Grashof was added to a growing list of propaganda stories used by the police to justify a massive nationwide search, with Federal Minister of the Interior Hans-Dietrich Genscher publicly declaring the RAF to be “Public Enemy Number One.” Apartments were raided in Gelsenkirchen, Frankfurt, Hamburg, and Bremen, yet the guerilla managed to elude capture.

Meanwhile, the trial of Horst Mahler, Ingrid Schubert, and Irene Goergens opened in West Berlin on March 1. Schubert and Goergens were charged with attempted murder and using force in the Baader jailbreak, while Mahler (who had arranged to be in court during the action, and so had an alibi) was charged as an accessory, and with illegal possession of a firearm.

This first RAF trial would set the tone for twenty years of collusion between the media, the police, and shadowy elements intent on presenting the guerilla in the most horrific light. The term “psychological warfare” was eventually adopted by the left to describe the phenomenon.

Already in February, police had announced that the RAF had plans to kidnap Chancellor Willy Brandt in order to force the state to release Mahler.3 The guerilla would subsequently deny this charge, claiming it was intended to make them look like “political idiots.”4

Then, on February 25, a seven-year-old boy was kidnapped. Newspapers announced that his captors were demanding close to $50,000 ransom as well as the release of “the left-wing lawyer in Berlin,” which journalists quickly explained must be a reference to Mahler.5

Clearly horrified, Mahler made a public appeal to the kidnappers to release the child.6 At the same time the provincial government of North Rhine-Westphalia agreed to pay the ransom—the boy was from a working class family that could not afford such a sum.7

Arrangements were made, a well-known lawyer agreeing to act as the go between. The money was delivered on Saturday February 27 and a young Michael Luhmer was released in the woods outside Munich, suffering from influenza but otherwise unharmed. According to the lawyer who personally delivered the money to the kidnappers, they denied being in the least bit interested in Mahler or anyone else from the RAF. Indeed, he came away with the impression that they were in fact “a rightist group like the Nazi party.”8 Police later announced that they suspected the son of a former SS officer of being involved in the plot.9

This first kidnapping occurred just as Mahler, Schubert, and Goergens were about to go on trial. This is what could be called a “false flag” action, a term referring to an attack carried out by certain parties under the banner of another group to which they are hostile in order to discredit them. As we shall see, false flag attacks were to plague the RAF throughout the 1970s, as all manner of antisocial crimes would be carried out or threatened by persons pretending to be from the guerilla.

The RAF repeatedly denied its involvement in these actions, and yet the slander often stuck.

Doubly vexing is the fact that in most of these false flag actions, no firm evidence has ever come to light proving who in fact was responsible. Suspicions have ranged from some secret service working for the state, or for NATO, or else perhaps neofascists, or some combination thereof. Or perhaps these were “normal” criminal acts, and it was the media or police who were fabricating details to tie them to the RAF.

Judging from experiences elsewhere in Europe, it is entirely possible that elements within the state, within NATO, and within the far right collaborated in some of these attacks. Such scenarios are known, for instance, to have played themselves out in France, Italy, and Turkey. The goal for such operations was generally not simply to discredit the left-wing guerilla, but rather to create a general climate of fear in which people would rally to the hard right.

In most cases, we may never know, but amazingly enough, there was a second false flag kidnapping during the first RAF trial, and the authors of this second crime actually ended up admitting the ruse.

On Sunday April 25, newspapers reported that a university professor and his friend had been kidnapped by the guerilla, which was threatening to execute them if Mahler, Schubert, and Goergens were not released. The kidnappers were allegedly demanding that the three be allowed to travel to a country of their choosing, and insisted that this be announced on television.1

Two days later, the men were found, one of them tied to a tree. The kidnappers, however, were nowhere in sight. After some questioning, the “captives” broke down and admitted that they had staged the entire thing in the hopes of scaring people into voting against the “left-wing” SPD in the provincial elections in Schleswig-Holstein.2 The mastermind behind this plan, Jürgen Rieger,3 was active in neofascist circles; he would eventually be sentenced to six months in prison as a result.

As a corollary to these staged actions, the police were happy to oblige by setting the scene at the trial itself:

The criminal court in the Moabit prison had been transformed into a fortress for the trial. There were policemen armed with submachine guns patrolling the corridors, the entrances and exits; outside the building stood vehicles with their engines running and carrying teams of men, there were officers carrying radio equipment, and more units waited in the inner courtyard to go into action if needed.4

Far-right hoaxes were helping to justify shocking levels of police militarization and repression. One did not need to be a paranoid conspiracy theorist to think that the state was more than willing to play dirty in order to get rid of its new armed opponents and that the talk of a “fascist drift” was more than mere rhetoric.

Not that the radical left was unwilling to fight for the captured combatants, though kidnapping innocent children or academics would never feature amongst its strategies. When kidnappings would eventually be carried out, the targets would always be important members of the establishment, men with personal ties to the system against which the guerilla fought.

In 1971, however, nobody was in a position to carry out such operations, and so the struggle for the prisoners’ freedom took place largely in the streets. As the trial wrapped up, rioting broke out for two days in West Berlin: “youths blocked traffic, and smashed store and car windows,” all the while shouting slogans like “Free Mahler!” and “Hands off Mahler!”5

Clearly, although its capacities were not yet developed, a section of the left was willing to carry out militant actions in support of the guerilla, while itself preferring to remain aboveground.

In late May, after twenty-two days in court, the verdicts came down. Goergens was sentenced to four years youth custody, and Schubert received a six-year sentence.1

It should be noted that both women would soon have additional years tacked on, as they also faced charges relating to various bank robberies.2

As for Horst Mahler, he was found not guilty, but was kept in custody as the state appealed the verdict. He was also facing additional charges stemming from the bank robberies.3

Throughout the trial, other combatants had been picked up by the state.

On April 12, 1971, Ilse Stachowiak was recognized by a policeman and arrested in Frankfurt. Known by her nickname “Tinny,” Stachowiak was probably the youngest member of the guerilla, having joined in 1970 at the age of sixteen.

The next day, Rolf Heissler was arrested trying to rob a bank in Munich. Heissler had previously been active in the Munich Tupamaros (a Bavarian group inspired by the West Berlin Tupamaros),4 but had followed his ex-wife Brigitte Mohnhaupt into the RAF.

Then, on May 6, not three months after her narrow escape in Frankfurt, Astrid Proll was recognized in Hamburg by a gas station attendant who called the police—she tried to escape by car, but was surrounded by armed cops and arrested.5

Two documents appeared about this time, each allegedly produced by the RAF. The first of these, Regarding the Armed Struggle in West Europe, was published under the innocent title “New Traffic Regulations” by the radical West Berlin publishing house of Klaus Wagenbach.6 Not only did this lead to Wagenbach receiving a suspended nine-month sentence under §1297—the catch-all “supporting a criminal organization” paragraph of the Orwellian 1951 security legislation—but the document was quickly disavowed by the RAF itself: it had been written by Mahler in prison, without consultation with any of the others, and did not sit well with the rest of the group.

While Mahler would remain in the RAF for the time being, this was the first visible sign of an ongoing process of estrangement between the former attorney and the rest of the guerilla.

Almost at the same time as Mahler’s document began to circulate, a second text, one which enjoyed the approval of the entire RAF, was released. On May 1, at the annual May Day demonstrations, supporters distributed what became known as the RAF’s foundational manifesto, emblazoned with a red star and a Kalashnikov submachine gun: The Urban Guerilla Concept. This text was widely reprinted, not only in radical publications like 883, but in the mainstream Spiegel, the result of a deal whereby the liberal weekly agreed to “donate” 20,000 DM to youth shelters.8

Drawing heavily on the guerillas’ experiences in the APO, and what they saw as the weaknesses of the New Left, The Urban Guerilla Concept tried to answer some of the questions people were asking about the RAF, while critiquing both the anarchist scene and the K-groups (referred to respectfully as “the proletarian organizations”). It also constituted an open invitation to join with the guerilla in the underground.

It was a document aimed at the seasoned activists of the left, speaking to their sense of frustration with the legal struggle in the hope that they might be won over to clandestinity.

This was Thorwald Proll’s closing statement in the Frankfurt Department Store Firebombing Trial. (M. & S.)

The trial for conspiracy to commit arson followed the trial for committing arson. But that’s obviously another question. Justice is the justice of the ruling class. Faced with a justice system that speaks in the name of the ruling class—and speaks dishonestly—we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. Faced with a justice system that forced a student couple underground by using laws regarding breach of the public peace and causing a disturbance from the year 1870/71 to sentence them to 12 months without parole, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves (breachers of the public peace, torch their ramshackle peace).

Faced with a justice system that uses laws from 1870/71 and then talks about what’s right—and speaks dishonestly—we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. Faced with a justice system that gave Daniel Cohn-Bendit1 (lex Benda, lex Bendit) an 8-month suspended sentence for jumping over a security fence, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. Faced with a justice system that, on the other hand, only pursued most Nazi trials in order to ease their own guilty right-wing conscience, trials in which they charge anyone that swore the Führer Oath2 as a criminal, an act which the entire justice system quite willingly engaged in itself in 1933; faced with a justice system like that, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves.

Faced with a justice system that prosecutes the minor murderers of Jews and lets the major murderers of Jews run around free, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. Faced with a justice system that in 1933 shamelessly plunged into fascism and in 1945 just as shamelessly deserted it, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. Furthermore, faced with a justice system that already in the Weimar Republic always sentenced leftists more heavily (Ernst Niekisch,3 Ernst Toller4) than right wingers (Adolf Hitler5), that rewarded the murderers of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht6 (and in so doing became complicit in their deaths), we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. Comrades, we want to take a moment to remember Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht—stand up!—the eye of the law sits in this court.

Faced with a justice system that never dismantled its authoritarian structure, but constantly renews it, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. Faced with a justice system that says might makes right and might comes before right (might is always right), we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. All power to freedom! Faced with a justice system that defends property and possessions better than it does human beings, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. Faced with a justice system that is an instrument of social order, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves.

Faced with a justice system that makes laws against the people rather than for them, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. Human rights only for the right humans (the state that leans to the right). Right is what the state does, and it’s always right. The state is the only criminal activity allowed. In a capitalist democracy such as this, in an indirect democracy such as this, it is possible for anyone to end up ruling over anyone, and that’s how it should stay, and don’t ask for how much longer. The ruling morality is bourgeois morality, and bourgeois morality is immoral. Bourgeois morality is and will remain immoral. If it is reformed, it will only result in a new form of immorality (and nothing more). Faced with a justice system that undermines the ethical underpinnings of the people (whatever they may be), we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. This state prosecutor is nothing more than a piece of the criminal justice system. He requested 6 years of prison time.

Furthermore, faced with a justice system that says it represents the people, but means that it represents the ruling class, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. Faced with a justice system that works to assure the ongoing reproduction of existing relationships, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. Faced with a justice system for which the (so-called) criminal class is and will remain the criminal class, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. What does return to society mean? Back to which society? Back to the capitalist society where you will have the opportunity to re-offend? Back to the bourgeois, capitalist society that is itself a prison, which amounts to going from one hole to another.

Every reform to criminal law only reforms the existing criminal injustice; criminal law is criminal injustice; the sentence is the injustice. I wouldn’t again offend against society, if they didn’t give me another reason to do so. How am I supposed to return changed to an unchanged society, and so on, and so forth. It is not the laws that need to be changed; it’s the society that must be changed. We want a socialist society. Faced with a justice system that plays homage to an abstract concept of law (Roman law is Bohemian law) and does not see individuals as the result of their society, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. Faced with a justice system that treats defendants as second-class citizens, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves.

Furthermore, faced with a justice system that is a system of the ruling class, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. (And furthermore) faced with a justice system that doesn’t reduce delinquency, but creates ever more of it (guilty verdicts and acquittals), we can’t be bothered defending ourselves (the outcome can only serve their interests). In an authoritarian democracy like this one, it can never amount to more than an assessment of guilt or innocence. The judge sentences the individual, not the society and not himself. What’s the magic word? The magic word is power, and it means the death of freedom! What do we have here that does not come from Nietzsche, that sociopath? For example, the will to power. You should think about power, but do not think that power thinks about disempowering itself at some point; ergo: destroy power (the question of power, the power of the question). Faced with a justice system that wants power and not freedom, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves (what freedom do you mean—bourgeois freedom is servitude, and socialist freedom is a long way off).

Furthermore, faced with a justice system that seeks to criminalize Kommune 1 and has persecuted them with an endless series of trials, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. Such a justice system should itself be put on trial. Faced with a justice system that seeks to criminalize a section of the SDS, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. How can the public peace of 1870/71 be broken in 1967/68? Yet again: torch this ramshackle peace!

Furthermore, faced with a justice system with a concept of law—a deceitful concept—that is shaped by the opinions of the ruling class (already the case with Franz von Liszt1 in 1882) we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. Furthermore, faced with a justice system that doesn’t see crime as a social phenomenon and which passes sentences that serve no social function (Franz von Liszt), we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. Faced with a justice system that speaks of punishment— meaning oppression, meaning repression—helping the offender, while in fact defending bourgeois society, always defending it, defending it to the end; faced with such a justice system, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves.

Quotes from the first draft of the reforms to the criminal code: “The bitter necessity of punishment.” “Responsibility lies with the law breakers” (and not the representatives of the law), “given the flawed nature of people” (and so it will remain in a capitalist society such as this, in which antiauthoritarian structures that promote perfection don’t exist and there are no examples of moral perfection—the principle of guilt, which guarantees the continuation of the principle of punishment, lives on, spelling the death of freedom and assuring the integrity of power). Another quote from the first draft of the criminal law reforms (this will be the last one): “(W)hat the principle of punishment presupposes is a virtually unchallenged standard of criminal law, etc., etc.” When will this stop?

Faced with a justice system that holds that the irrational standards of criminal law and criminology are appropriate, that denies the reality of the capitalist social order, that denies and suppresses psychology and the study of crime in a particularly nauseating way, constantly impeding them, that treats criminology as a science of social relationships; faced with such a justice system, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. Furthermore, faced with a justice system that represents the law of the ruling class—represents duplicity—we can’t be bothered defending ourselves.

Furthermore, bourgeois morality is and remains immoral, and if reformed, it is only as a new immorality. All attempts at reform are pointless, because they are inherent to the system. We demand the resignation of Minister of Justice Heinemann (also a pointless demand). Where is the judge who will turn his back on this crap and join the general strike, instead of remaining eternally stuck up to his armpits in this shit? Where are the antiauthoritarian judges? I can’t see them. This is your chance, Herr Zoebe,1 to be the first. I wrote that before I knew you. Later, you responded to the word democracy like it was leprosy, which is to say, you shrunk away from the concept. And for you, resocialization sends you into a rage; it’s the final blow. And for you it should be the final blow. Always: the final blow.

Faced with a justice system that has completely authoritarian judges, like the judge Schwalbe,2 we can’t be bothered defending ourselves (but one Schwalbe doesn’t make for an authoritarian summer). Faced with a justice system that has judges like the judge in Hamburg, who on August 15 of this year, following a 2½12; minute hearing, sentenced a young worker to 4 months with the possibility of parole, beginning at Easter, with the comment that the young worker should be happy—in spite of the brevity of the hearing—that he was given a chance to clarify his political motivations, and then went on to tell this young worker that he should stop worrying about things that don’t concern him; faced with a justice system that is made up of such judges, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. Yet again: torch this ramshackle peace.

Faced with a justice system that has judges like those that presided over the Timo Rinnelt trial,3 once more extending the reach of the German billy club, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves.

And finally, faced with a justice system that has judges like the judge presiding in the case against Jürgen Bartsch,4 who was sentenced to life imprisonment on the grounds that if he had wanted to he could have struggled to control his abnormal appetites (whatever that means), with the judge saying in conclusion, “And may God help you to learn to control you appetites”—so God and not society—and for such a judge it would be preferable if he had never been born or had died long ago; faced with such a justice system, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves.

It has been said that the trial of Jürgen Bartsch was the trial of the century. It was actually a trial against this century, and the sentence spoke for this century, which is to say, it spoke for the morality of the preceding century (it will only get worse), which in this trial was celebrated as a barbaric triumph. When the judgment was read, the spectators, a petit bourgeois gathering, clapped and cheered. Nobody forbid that. The teeth of justice were chattering, but nobody heard that. Child murderers are useful. They eliminate all consciousness that criminals were once themselves children (the authoritarian upbringing). A hundred children of West German families are beaten to death every year. Beaten to death. Child murderers work to ease our conscience about this slaughter. And what of the daily murder of children in Vietnam (with its breathtaking body-count)? What do respectable people pray for? Today we get our daily ration of murder (The Springer papers are the centerpiece of every breakfast).

Furthermore, bourgeois morality is the ruling morality, and bourgeois morality is immoral. Faced with a justice system that has state prosecutors like state prosecutor Griebel,5 who told me “under four eyes”6 that he holds Marx’s teachings in the highest regard (but what does he do about it?), that he is as much a prisoner of a labyrinthine bureaucracy as I (but what does he do against it?). He accuses the left here of only wanting to change superficial things, but nothing beyond that (but he bears the mark of Cain of repression on his forehead), and he had the effrontery to bare his broken bourgeois heart to me, saying that on the one hand he is troubled by the rigidity of the ruling conditions, while on the other—how grotesque—he continued to speak of the legitimacy of the laws of 1870/71—speaking deceptively—faced with such a justice system, I can’t be bothered defending myself, and we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. Imprison the state prosecutors. Where is the state prosecutor who will indict the state?

Faced with a justice system that is charging us with life-threatening arson, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. Faced with a justice system, in the eyes of which, we have every reason to believe, we are politically tainted from the outset, we cannot defend ourselves (all the charged are arsonists and all judges are honest men). Yet again: torch this ramshackle peace.

And furthermore, faced with a justice system that speaks for the ruling class—and speaks deceptively—we can’t be bothered defending ourselves.

Faced with a justice system with custodial judges as authoritarian as judge Kappel, who gave every impression of being convinced of the guilt (whatever that is) of all of the accused before the trial even started. Amongst other things, his macho aggressiveness is such that he said to me, “Take your hand out of your pocket.” When I put my other hand in my pocket (obviously not the same one), he didn’t say anything, he just laughed, and my laughter caught in my throat at the thought that he and I could ever laugh at the same thing for the same reason—a question of consciousness. Faced with such a justice system, I can’t be bothered defending myself, and we can’t be bothered defending ourselves.

Faced with such a decadent justice system, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves (a legal right is only what is right legally). Faced with a justice system that grotesquely misuses detention, I can’t be bothered defending myself. If you have a fixed address, the justice system holds on to you until you lose it, which is to say, until you’re tossed out. Then the justice system says, “Ah, you don’t have one. In any event, if you’re released you will no longer have one. That essentially makes you a flight risk.” Faced with a justice system that grotesquely abuses preventive detention, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. In this way they reveal the abyss that is the justice system. If you have a fixed address, the police make sure you lose it, so they can take you into custody. It happened to August Klee, who like me has been held in detention for some months now. While all of this has not been enough to convince me that life is a theatrical drama, I do believe that the remand centre can be. When Klee was detained in this way, the police assured him that it was not the first time they had done this; making the criminal police potential criminals.

Risk of flight always offers the necessary excuse. For instance, August Klee is also classified a flight risk because his closest relatives, first and foremost among them his wife, live outside of Germany. He must divorce her (what’s that about?) if he wants to get out. On the other hand, if you live in Germany, but do not live with your wife (what’s that about?), if you have no family ties (because you’re not chained to that structure), then you’re a flight risk. If you lived outside the country 40 years ago, you’re a flight risk. If you’ve recently come back from a trip (and not from some crappy tourist trip), in that case you’re a flight risk. If you’re a foreigner, then you’re a flight risk. (I can recite all of this by heart). If there is a mix-up of some sort in your arrest, as occurred recently on Hammelsgasse (bourgeois freedom is a Hammelsgasse1), there’s no need for concern, phony paperwork will be prepared. Here the danger is that one will be silenced.

Following conviction, it may be the case that you will be released for good behavior. He, however, has been refused this, because he has behaved so well that he has become institutionalized, and will surely be unable to find his bearings on the outside. He must remain inside until the end. This is an example of the risk of unadorned reconstruction. If you happen to be an arsonist, there is the danger of evidence being suppressed, etc.; faced with such a justice system, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves.

Faced with a justice system that supports a prison system that attacks and violates the personal freedom and dignity of 365 people every second—first the attack, then the violation—we can’t be bothered defending ourselves.

What is permissible and what is not permissible in remand: prisoners in remand are permitted to do what the justice system—acting as administrators—permits them to do. You are not permitted to be afraid. You are not permitted to lie around in bed, but you can lie under the bed. You are not permitted to play ping-pong with multiple balls; you are only permitted one ball. You are not permitted to refuse dinner; you are not permitted to show any kind of defiance. As a revolutionary socialist, you can never show defiance.

A rate of 1.23 DM1 per day is designated for meals (what a fantastic amount). You are not permitted to throw your dinner in the guard’s face, or he’s not responsible for what happens next. The guards are prisoners just like you, and most of them know it. The guards are only the little warlords.

You are not permitted to smoke outside of your cell, only in it. You are permitted to experience the hell of it all inside your cell. You are not permitted to light fires, because you can’t use the fire alarm, because you can’t reach it, because you can’t leave your cell, because the door is locked.

You are not permitted to take the opportunity to engage in discussion with the other prisoners, the so-called criminals, whatever might come out of it. Let’s be perfectly clear, they are staple products of the capitalist social order. You need to be clear about this.

Furthermore, you are not permitted to hang anything on the walls, but you are permitted to hang up the memo that tells you that you are not permitted to hang anything on the walls. You are not permitted to loiter. You are not permitted to lean against the wall. You are not permitted to just hang around. You should spend every day formulating a more thorough understanding of the justice system.

If you go to see the minister, don’t forget it’s just a crutch. Don’t go to church; God is dead, but Che lives. Study the rudiments of socialism, and you will have everything you need.

You are only permitted a half-hour a day to walk. You are not permitted to yell out the window. You are not permitted to have as many comrades as you like. You are permitted to spend 35 DM2 per week. That’s how it goes in Hessen. And don’t forget, Hessen has the most liberal penal system. You are not permitted to drink as much coffee as you wish. You are not permitted to drink any alcohol. You are not permitted to smoke hash. You are not permitted to consume in the way you wish, and you are not permitted to consume what you wish, and all of that in a society based on consumption. Note that in prison consumption becomes a treat.

Correspondence is monitored. Sexual intercourse is not monitored, but then there’s not much of it. Adultery is not permitted (what’s that about?), but it is not permitted to consummate a marriage (what’s that about?). All of those in the hole who still cling onto bourgeois existence (woe be it to those who see no alternative), and that’s most of them, will be driven crazy by the bourgeois social order. That’s how it is. How, for instance, are they to maintain their marriages? They will all fail, and that’s good.

Every citizen should go to prison to gain a real understanding of the situation.

Every socialist should go to prison to gain a real understanding of the situation.

Every citizen should go to prison so that he develops a correct relationship to socialism.

Yet every individual capitalist or socialist has the opportunity to be the first to blow up a prison. Don’t read any of the Springer papers; burn them. Then blow Springer up.

You are not permitted to beat off or masturbate if that’s what you want to do. You can do what you want with your body. The duality of homosexuality exists. If new sexual laws are passed, will you still be permitted to fuck chicks; not to speak of other prisoners. In Butzbach penitentiary there was a flourishing trade in bras. Forced sodomy (what’s that all about?). Rape the guards that torment you.

You aren’t permitted to commit a break-in, but you are permitted to break out. Out of prison I mean. Attempted escape is not an indictable offense. You are not permitted to receive photos 1-3 from the Kommune 1 book, Klau Mich,3 because their obscene content is a threat to the moral order of the remand centre.

The way Glojne, alias Globne, the Regional Court Judge explained it to me in a letter—who asked?—you are not permitted to hang anything in your cell or hang yourself in the cell. You are not permitted to hide in your cell. Try it some time. You are not permitted to take anything from the library. You are not permitted to lose your mind. You are permitted to buy food and specialty items, as well as other items you require in keeping with a reasonable lifestyle. You are not permitted to violate these conditions. The administrators decide what reasonable means (each individual administrator in this mental asylum).

If for reasons of order they want to reduce the number of newspapers and magazines you receive, you must attempt to have them delivered to you by means of disorder—in the sense of antiauthoritarian order. You must pull them out of the guard’s hands, just as he pulled them out of yours. You have to try. You can’t give up without trying. If the warden addresses you with du, you must also address him with du.1 You mustn’t work—for 80 pfennig2 a day. You can’t let yourself be exploited. The justice system practices the most secretive, most efficient and most disgraceful exploitation possible. It fattens itself by using primitive capitalist techniques in a modern capitalist system. Grievances are pointless, particularly as you are not permitted to file common grievances. Grievances are suppressed at will. Grievances are pointless, because you must submit them to the ruling structure. Common dispositions are common dispositions, and solitary dispositions are solitary dispositions. You can’t give in to loneliness. You can’t lose the dialogue. You can’t lose the socialist dialogue. In prison you have nothing to lose and lose nothing. You have everything to win.

Note that the rights and responsibilities of remand prisoners mentioned here are an introduction to inequality and bondage; you’re a first class citizen, you’re a second class citizen, you’re a fourth class citizen, you’re a fifth class citizen, etc., and that’s what you’ll remain. You’re a criminal and that’s what you will remain. Conduct regarding the attendants: the prisoner must immediately disengage himself from the attendants; he must immediately disengage.

Life in the penal institution is one in which work time, free time, and quiet time are carefully divided, and the prisoner is bound to this division. Life in the penal institution is life in barracks. It consists of sitting around. Life in the penal institution is divided into time for oppression, time for bondage, and time of dead silence. The time of unconsciousness is over. The time for realism has begun. Bourgeois life is its own kind of remand. If you didn’t already know that, now you do. You are not permitted to live and you are not permitted to die; you are not permitted to die and you are not permitted to live. Exactly. You are not permitted to run amok in the house. You are not permitted, of your own free will, to leave your assigned place. You are not permitted to break out. You are not permitted to scream, yell, or speak out the window. You aren’t allowed to speak to your cellmates (what’s that about?). You are not permitted to threaten the security of the institution. You are not permitted to withhold, store, or use anything. You are not permitted to retain anything, etc.

You must do everything that you are not permitted to do, and you must not let your guard down. Always think about it. Send every state prosecutor to prison. You are not permitted to defend yourself. Never. Those who defend themselves incriminate themselves. Do forget that. You are not permitted to have unauthorized telephone contact. Your correspondence is monitored. Letters you send from prison cannot be sealed. You are not permitted to seal them yourself. You are not permitted to… You are not permitted to…

You cannot give in to fatigue. You cannot, at risk of retribution, pass parliamentary representative Güde3 in the street without pushing him around. He brings out the best in you. But beforehand you must paint your hand red. The left one, obviously.

Yet again (in the hole), you cannot give in to fatigue. Concentrate. You’re sitting in bourgeois capitalism’s concentration camp. Beyond that, the prisoner has a cell to keep clean. The most oppressive power in prison is the power of cleanliness. Cleaning is the major form of torture. You are not permitted to get dirty while cleaning things. Only clean up when it suits you. Otherwise you aren’t in prison; prison is in you. Keep in mind: the cleaner the cell, the more complete the hell. Furthermore, the prisoner and his seven suitcases4 and his cell can be searched at any time. When you are searched, ask them if they’re looking for new people, etc., etc.

I can’t continue talking about this. Faced with a justice system that has such an indescribable prison system, we can’t be bothered defending ourselves. Such a justice system must itself be indicted. Such a justice system must be exposed by the revolutionary process. It is the responsibility of every antiauthoritarian judge to take legal action against this justice system. We encourage the antiauthoritarian segment of the justice system to use its strength to call a general strike. We particularly encourage antiauthoritarian interns to call a general strike.

I declare my solidarity with Gudrun Ensslin and Andreas Baader, although they have chosen to defend themselves here, which was obviously a decision that no one really understood. This solidarity will continue through the next period while they are in prison and the penitentiary. I have, in any event, every reason to do so. I declare my solidarity with Horst Söhnlein. And if I do so, although he chose not to defend himself, it is as much prollidarisch1 as it is in solidarity. And with that, I stop.

We declare our solidarity with all of the actions that the SDS has undertaken in response to the recent attempts to undermine their public support. We demand the abolition of judicial unaccountability, because they use their power to assure the rule of some people over other people.

We demand the abolition of the power of some people over other people.

Workers of the world unite!

Venceremos!

Thorwald Proll

October 19682

Comrades of 883,

It is pointless to explain the right thing to the wrong people. We’ve done enough of that. We don’t want to explain the action to free Baader to babbling intellectuals, to those who are freaked out, to know-it-alls, but rather to the potentially revolutionary section of the people. That is to say, to those who can immediately understand this action, because they are themselves prisoners. Those who want nothing to do with the blather of the “left,” because it remains without meaning or consequence. Those who are fed up!

The action to free Baader must be explained to youth from the Märkisch neighbourhood, to the girls from Eichenhof, Ollenhauer, and Heiligensee, to young people in group homes, in youth centers, in Grünen Haus, and in Kieferngrund.3

To large families, to young workers and apprentices, to high school students, to families in neighborhoods that are being gentrified, to the workers at Siemens and AEG -Telefunken, at SEL and Osram, to the married women who, as well as doing the housework and raising the children, must do piecework—damn it.

They are the ones who must understand the action; those who receive no compensation for the exploitation they must suffer. Not in their standard of living, not in their consumption, not in the form of mortgages, not in the form of even limited credit, not in the form of midsize cars. Those who cannot even hope for these baubles, who are not seduced by all of that.

Those who have realized that the future promised to them by their teachers and professors and landlords and social workers and supervisors and foremen and union representatives and city councilors is nothing more than an empty lie, but who nonetheless fear the police. It is only necessary that they—and not the petit bourgeois intellectuals—understand that all of that is over now, that this is a start, that the liberation of Baader is only the beginning! That an end to police domination is in sight! It is to them that we want to say that we are building the red army, and it is their army. It is to them that we say, “It has begun.” They don’t pose stupid questions like, “Why right now precisely?” They have already traveled a thousand roads controlled by the authorities and managers—they’ve done the waiting room waltz; they remember the times when it worked and the times when it didn’t. And in conversations with sympathetic teachers, who are assigned to the remedial schools that don’t change anything, and the kindergartens that lack the necessary spaces—they don’t ask why now—damn it!

They certainly won’t listen to you, if you aren’t even able to distribute your newspaper before it is confiscated. Because you don’t need to shake up the left-wing shit eaters, but rather the objective left, you have to construct a distribution network that is out of the reach of the pigs.

Don’t complain that it’s too hard. The action to free Baader was hardly a walk in the park. If you understand what’s going on (and your comments indicate that you do understand, so it’s opportunism to say that the bullet also hit you in the stomach1—you assholes), if you understand anything, you need to find a better way to organize your distribution. And we have no more to say to you about our methods than we do about our plans for action—you shitheads! As long as you allow yourselves to brought in by the cops, you aren’t in a position to be giving anyone else advice about how to avoid being brought in by the cops. What do you mean by adventurism? That one only has oneself to blame for informers. Whatever.

What does it mean to bring conflicts to a head? It means not allowing oneself to be taken out of action.

That’s why we’re building the red army. Behind the parents stand the teachers, the youth authorities, and the police. Behind the supervisor stands the boss, the personnel office, the workers compensation board, the welfare office, and the police. Behind the custodian stands the manager, the landlord, the bailiff, the eviction notice, and the police. With this comes the way that the pigs use censorship, layoffs, dismissals, along with bailiff’s seals and billy clubs. Obviously, they reach for their service revolvers, their teargas, their grenades, and their semi-automatic weapons; obviously, they escalate, if nothing else does the trick.2 Obviously, the GIs in Vietnam are trained in counterguerilla tactics and the Green Berets receive courses on torture. So what?

It’s clear that prison sentences for political activities have been made heavier. You must be clear that it is social democratic bullshit to act as if imperialism—with all its Neubauers3 and Westmorelands,4 with Bonn, the senate, Länder youth offices, borough councils, the whole pig circus—should be allowed to subvert, investigate, ambush, intimidate, and suppress without a fight. Be absolutely clear that the revolution is no Easter March. The pigs will certainly escalate their means as far as possible, but no further than that. To bring the conflict to a head, we are building the red army.

If the red army is not simultaneously built, then all conflict, all the political work carried out in the factories and in Wedding5 and in the Märkisch neighborhood6 and at Plötze7 and in the courtrooms is reduced to reformism; which is to say, you end up with improved discipline, improved intimidation, and improved exploitation. That destroys the people, rather than destroying what destroys the people! If we don’t build the red army, the pigs can do what they want, the pigs can continue to incarcerate, lay off, impound, seize children, intimidate, shoot, and dominate. To bring the conflict to a head means that they are no longer able to do what they want, but rather must do what we want them to do.

You must understand that those who have nothing to gain from the exploitation of the Third World, of Persian oil, of Bolivian bananas, of South African gold, have no reason to identify with the exploiter. They can grasp that what is beginning to happen here has been going on for a long time in Vietnam, in Palestine, in Guatemala, in Oakland and Watts, in Cuba and China, in Angola and in New York.

They will understand, if you explain it to them, that the action to liberate Baader was not an isolated action, that it never was, but that it is just the first of its kind in the FRG. Damn it.

Stop lounging around on the sofa in your recently-raided apartment counting up your love affairs and other petty details. Build an effective distribution system. Forget about the cowardly shits, the bootlickers, the social workers, those who only attempt to curry favor, they are a lumpen mob. Figure out where the asylums are and the large families and the subproletariat and the women workers, those who are only waiting to give a kick in the teeth to those who deserve it. They will take the lead. And don’t let yourselves get caught. Learn from them how one avoids getting caught—they know more about that than you.

DEVELOP THE CLASS STRUGGLE

ORGANIZE THE PROLETARIAT

START THE ARMED STRUGGLE

BUILD THE RED ARMY!

RAF

June 5, 1970

We must draw a clear line between ourselves and the enemy.

Mao

I hold that it is bad as far as we are concerned if a person, a political party, an army or a school is not attacked by the enemy, for in that case it would definitely mean that we have sunk to the level of the enemy. It is good if we are attacked by the enemy, since it proves that we have drawn a clear dividing line between the enemy and ourselves. It is still better if the enemy attacks us wildly and paints us as utterly black and without a single virtue; it demonstrates that we have not only drawn a clear dividing line between the enemy and ourselves but have achieved spectacular successes in our work.

Mao tse Tung

May 26, 19391

1. CONCRETE ANSWERS TO CONCRETE QUESTIONS

I still insist that without investigation there cannot possibly be any right to speak.

Mao2

Some comrades have already made up their minds about us. For them, it is the “demagoguery of the bourgeois press” that links these “anarchist groups” with the socialist movement. In their incorrect and pejorative use of the term anarchism, they are no different than the Springer Press. We don’t want to engage anyone in dialogue on such a shabby basis.

Many comrades want to know what we think we’re doing. The letter to 883, in May 1970, was too vague. The tape Michele Ray had, extracts of which appeared in Spiegel, was not authentic and, in any event, was drawn from a private discussion. Ray wanted to use it as an aide-mémoire for an article she was writing. Either she tricked us or we overestimated her. If our practice was as hasty as she claims, we’d have been caught by now. Spiegel paid Ray an honorarium of $1,000.00 for the interview.

Almost everything the newspapers have written about us—and the way they write it—has clearly been a lie. Plans to kidnap Willy Brandt are meant to make us look like political idiots, and claims that we intend to kidnap children are meant to make us look like unscrupulous criminals. These lies go as far as the “authentic details” in konkret #5, which proved to be nothing more than unreliable details that had been slapped together. That we have “officers and soldiers,” that some of us are slaves of others, that comrades who have left us fear reprisals, that we broke into houses or used violence to take passports, that we exercise “group terror”—all of this is bullshit.

The people who imagine an illegal armed organization to be like the Freikorps or the Feme,1 are people who hope for a pogrom. The psychological mechanisms that produce such projections, and their relationship to fascism, have been analyzed in Horkheimer and Adorno’s Authoritarian Personality and Reich’s Mass Psychology of Fascism. A compulsive revolutionary personality is a contradictio in adjecto— a contradiction in terms. A revolutionary political practice under the present conditions—perhaps under any conditions—presumes the permanent integration of the individual’s personality and political beliefs, that is to say, political identity. Marxist criticism and self-criticism has nothing to do with “self-liberation,” but a lot to do with revolutionary discipline. It is not the members of a “left organization,” writing anonymously or using PEN names, who are just interested in “making headlines,” but konkret itself, whose editor is currently promoting himself as a sort of left-wing Eduard Zimmermann,2 producing jack-off material for his market niche.