18 - Slave-hunter

There was a sound like approaching thunder, pebbles sprayed, and a high whinnying split the air. The hide curtain beside Rye was ripped aside, and he found himself staring out at the furious face of a woman on horseback.

Terrified by the hissing vehicle, the horse was plunging and crying out. Pushing a smoking, stubby black tube into her belt, the woman slashed at the animal savagely with a short whip, ordering it to be still, till at last it obeyed, trembling and sweating.

‘Didn’t you hear me calling, you buffoon?’ the woman shouted at Rye. ‘Get back off the road! There’s a cart coming behind me from the Harbour. You’ll have to wait till it’s passed. Our mission is urgent. We don’t want to be stuck behind this lumbering monstrosity all the way through the—’

She broke off, frowning. She peered through the doorway at Bean in the driver’s seat, at the small people huddled together in the back of the wagon.

‘What’s this?’ she demanded.

‘The Master’s business,’ Rye said, raising his chin.

‘No business I’ve heard of,’ the woman said slowly. ‘And who, might I ask, are you?’

‘Who I am is not your affair,’ said Rye, putting as much cold pride into his voice as he could. ‘It is enough for you to know that I am the Master’s servant, and my task is of great importance to him.’

‘Is it, indeed?’ the woman murmured. She stood up in the stirrups and looked over the wagon at the guards staring out through the gates.

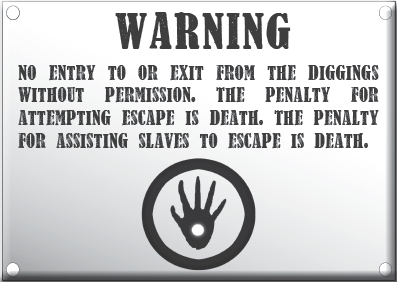

Rye looked too, and for the first time read the notice fixed to the mesh.

‘Guards!’ the woman shouted. ‘Why have you allowed these mine rats to leave their work? Explain yourselves!’

The guards glanced at one another in confusion. They muttered together for a moment, then one slipped through the gates and came running. It was Krop 1 or Krop 4, Rye thought, because the grey paper was in his hand.

‘We were only obeying orders, Kyte,’ the guard mumbled, handing the paper to the woman. ‘We know Brand’s sign—seen it often enough.’

Kyte! Rye’s stomach turned over. ‘Kyte’ was the name on the top of the orders! Kyte was the slave-hunter who had led the invasion of Nanny’s Pride farm!

The woman glanced at the paper. Her face darkened. ‘You dolts!’ she snarled.

‘Get out!’ Bird’s frantic cry rang out, echoing around the bare walls of the wagon. ‘Run!’

Bean slammed his hand down on a lever. Steam gushed, hissing, from beneath the wagon, smothering it in a billowing white cloud. As Kyte’s horse squealed and reared in terror, knocking the guard beside it to the ground, Bean hurled himself sideways out of the driver’s seat, onto the track. Stocky figures bolted out of the storage space and began scrambling after him.

‘Run!’ screamed Bird. ‘Bell! Chub! All of you—’

Kyte yelled in fury, fighting to control her panicking mount. The guards behind the gates hesitated, blinded by the steam. Rye leaped off the jell safe and began trying to fight his way through the press of fleeing slaves, towards Sonia.

There was a sharp crack, and a flash of white light lit up the wagon. The flash lasted only an instant, just long enough for Rye to glimpse ragged figures caught in mid-stride, Bird’s mouth wide open in a soundless cry, Itch half-turned with his knife in his hand, Chub crouched beside a man who seemed to have fallen.

They were all completely motionless. And in the same split second Rye realised that he, too, had frozen where he stood. He could not move a finger.

It was as if time itself had stopped. But only inside the wagon. Outside, there was noise and activity. Outside there was shouting, scuffling, cursing, the hissing of steam, the rumbling of approaching wheels, the thudding of fast-running feet. And there was Kyte’s voice, high and dominating, rising above everything else.

‘Krops, stay where you are! Stay, you fools, and hold the ones you’ve got! I’ve quelled the scum in the wagon—and the enemy spy who’s leading them, too. The strays can be rounded up later. Good! Here are my Baks with the cart!’

The sounds of wheels and running feet grew louder, slowed, then stopped. Rye tried desperately to turn his head so he could see what was happening on the track, but it was hopeless.

He could only imagine the cart coming to a stop beside the wagon. He could only imagine Kyte looking down from the back of her cowed horse at another set of inhuman grey-clad guards panting between the cart’s shafts.

‘Take the trench-bridge from the cart, Baks!’ he heard Kyte order. ‘We won’t need it now. Then turn the cart around. By chance we’ve been spared the journey to the Den. We don’t need Scour scum for the Master’s test any more. These traitors will do just as well.’

‘But Kyte,’ whined a Diggings guard, as the clatter of falling wood and the sound of turning wheels signalled that the woman’s order was being obeyed. ‘Can’t we at least have the mine rats back? We’re shorthanded as it is!’

‘Silence!’ Kyte snapped. ‘The penalty for trying to escape the Diggings is death. Isn’t that so?’

‘Yes, Kyte,’ the guard mumbled.

‘Yes!’ cried Kyte. ‘So these scum are doomed to die in any case. And if I were you, Krop, I’d think twice about questioning my orders. You made a bad mistake tonight. If I hadn’t come along—’

‘It wasn’t our fault,’ the guard protested. ‘The spy showed the Master’s paper, with Brand’s signature at the bottom. How did he lay his hands on it?’

There was a tiny pause. Rye knew why. Kyte was well aware that it was her error that had allowed the grey paper to fall into Bird’s hands.

‘It doesn’t matter where the paper came from!’ the woman snapped, recovering. ‘What matters is that somehow the spy knew where the mine rats he wanted worked, and which hut they slept in.’

‘It was not the Krops who told!’ exclaimed the guard. ‘The Krops would never betray—’

‘Luckily for you,’ Kyte cut in smoothly, ‘I’m in a good mood because I’ve been spared a tedious journey to the Den. So I’ll destroy the paper and say nothing of it to Brand. I’ll report that a spy made use of the jell-trader’s wagon to enter the Diggings, and tried to steal the slaves by force.’

‘Thank you, Kyte. The Krops are in your debt.’

The guard sounded very subdued. The woman’s reply was coldly triumphant.

‘Very well. Forget the paper ever existed, and you’ll be safe. And don’t open the gates again for any reason till I tell you to do it. Do you understand me?’

‘Yes, Kyte.’

‘Now, load the prisoners into the cart. Yours first—the quell will hold mine a bit longer. Tie their wrists and ankles, but don’t harm them. They’re to be delivered in good condition. The Master wants them to be able to run.’

Kyte’s final words echoed often in Rye’s mind during the long, jolting journey that followed. Bound hand and foot, lying packed together with the other prisoners beneath a canvas cover that hid the sky, he could not forget them. They kept coming back to him like a hideous refrain.

The Master wants them to be able to run …

What horror awaited him at the Harbour?

He had no idea how many others lay with him in the cart. Four-Eyes had been found, released from the sack, and left in the driver’s seat of the wagon, still fast asleep. But Bird had been taken, he knew. He had seen her carried out of the storage space with Sonia. Bean was here also. The Diggings guards had grabbed him as he stood helping others to jump down from the wagon. And Itch was here. And Chub and her husband, whose name seemed to be Pepper.

But there were many of the slaves from Tunnel 12 as well—all those who had not managed to escape in those first few moments of confusion. Rye could hear them whispering to one another. Every now and then he would catch a name. Lucky. Giggle. Bud …

Lucky, Giggle, Bud, Chub, Bird, Itch, Bean—what sorts of ridiculous names are they? Rye thought with a flash of useless irritation. And slowly it dawned on him that all the names of the people he had met since going through the silver Door were strange. Bones. Needle. Cap. Four-Eyes …

Then he saw it. Nicknames! They were nothing but nicknames!

The people here believed in the old tale, long forgotten by almost everyone in Weld, that those who know your true name have power over you. They kept their real names secret from everyone but their closest family and friends.

And perhaps this was wise. Perhaps it was their only defence against the sorcerer who had first led them, then enslaved them. Not knowing their names, the Master could control their bodies, but not their minds.

Of course! That was why Rye’s careless use of the name FitzFee had caused Bird to react so savagely. Bird’s family name must be FitzFee too. She had thought Rye was trying to enchant her!

If only I had been, Rye thought drearily. And if only I had succeeded. Then Dirk, Sonia and I would be together now, facing only the dangers of the Scour. And the bag of powers would still be with me, safe around my neck.

After a while, he lost all sense of time. And gradually the murmuring of the other prisoners, the bumping of the cart, the pounding of the guards’ feet, merged and became parts of confused, nightmarish dreams.

He seemed to see Dirk waking, groggy with myrmon, on the track far behind him. He seemed to see Bones sitting alone by the sled at the Den, his head in his hands.

And he seemed to see Sonia lying somewhere very near, somewhere in the rattling cart, coming to consciousness and searching frantically for some sign of him.

Hazily, knowing he was caught in the web of a waking dream, he sent his thoughts to her.

Sonia, I am here with you! Sonia, we are captured—being carried to the Harbour.

Rye sent the message, as so often he had sent urgent thought messages in the past, without any real hope that it would be received. But this time something was different. Faintly, so faintly that he could not be sure it was real, an answer came to him.

The nine powers. Can you or Dirk reach …?

The stab of pain he felt made him reply abruptly, without thought.

The bag of powers is lost. Dirk too. Lost.

Sonia’s horror rolled like a wave through his mind, making him gasp and blink. Then, quite suddenly, there was another feeling—a feeling, almost, of joy—startled joy!

Rye, we are talking to each other in our minds!

Yes, Rye thought in amazement. But how can that be?

Am I dreaming? He sent the message cautiously.

If you are, then I am too, the reply shot back, clearer than before. And then another message came, tumbling after the first and tinged with dread. Rye, I can smell the sea.

Rye hesitated. And slowly, through the mingled odours of canvas and sweat, he too detected the tangy scent of salt water and seaweed.

He had been relying on his sense of hearing to warn him that the journey was ending. He had been waiting for the dull, regular boom of waves pounding on a shore, like the sound that had dominated the city of Oltan.

There was no sound of waves here. Yet now that he had become aware of it, it seemed to him that the smell of the sea was growing stronger by the moment.

And the cart was slowing. Slowing, turning … and stopping.

Rye—

Sonia’s voice clamoured in his mind, sharp with fear, then broke off abruptly. Rye knew why. Sonia did not want to burden him with her terror.

We will find a way out of this, Sonia. We will survive, as we did in Oltan.

He sent the message as firmly as he could, but the only reply was a faint brush of warmth. Sonia was holding her thoughts back. No doubt she could not stop herself from remembering that it was the Fellan powers that had saved them in Oltan, and the powers were gone.

The canvas above Rye was pulled aside. He lay blinking up at a canopy of weirdly glowing clouds. The smell of the sea rolled over him, driven by a small, sour breeze. The odour was heavier, oilier than the smell of Oltan bay. And there was still no sound of breaking waves—only a soft lapping, and a faint, dull rumbling that seemed to be coming from far away.

Grey-clad arms seized him and he was lifted from the cart and set roughly on his feet. He found himself standing on a flat, paved space flooded with white light that banished the darkness of the night completely. Directly in front of him was a blank grey wall, so long that he could not see where it began or ended.

Swaying, he looked up, trying to judge the wall’s height, trying to see any way it could be climbed. And to his dazed astonishment he saw a low roof studded with air vents, and pipes from which steam rose.

This was not a wall, but a building—a building with no windows and no doors. A building so vast that it seemed to go on forever.

An iron hand held him upright as the bonds that bound his ankles were cut. All around him the other captives were being dealt with the same way. Many were staggering and falling to their knees the moment they were no longer supported.

But no one made a sound—not a single gasp or groan escaped anyone, let alone a plea for mercy. Those who managed to remain on their feet helped those who had fallen. And when the cart was empty, and Kyte strode forward to confront her prisoners, she found the people of Nanny’s Pride farm, re-captured slaves and failed rescuers alike, standing shoulder to shoulder, staring straight ahead, refusing to show their fear.

Rye felt a strong surge of emotion flow into his mind, mingling with the respect and admiration he was already feeling. He looked across the heads of the silent crowd and met Sonia’s shining eyes.

‘So the rats are feeling brave,’ sneered Kyte. ‘I’ll enjoy seeing how brave you are when tomorrow comes, little rats!’

Turning her back on them, she took a slim grey tube from her belt and pointed it at the building. A square section of the grey wall slid noiselessly to one side.

Rye felt sweat break out on his forehead. The opening in the wall shone bright white. Evil streamed from it like water.

‘Guards!’ shouted Kyte. ‘Take them in!’