1

The Stand-up Auteur

Cecilia Sayad

Woody Allen’s films have always addressed particular aspects of American culture – Jewish humor, local identities (Brooklyn, Manhattan, California), politics (his aversion to Republicans), and aesthetic tastes (his love of Hollywood classics, art cinema, jazz). But the director’s channeling of cultural identities and debates goes beyond the plots of his films. Allen’s public image, a combination of his screen persona and his public discourse, has invariably embodied a tension that was central to the definition of a film culture in the United States: that between “high” and “low” cultural objects – to put it bluntly, between enduring art and disposable entertainment.

It is a well-known fact that the French-born idea of the auteur became a valuable tool in the ascription of cultural value to films. The term’s designation of stylistic and thematic consistency, as well as of a director’s self-expressive needs, counterbalanced the formulaic and ephemeral aspects of industrial objects produced for mass consumption. We are also aware that Allen’s recurring themes and stylistic tropes have placed the majority of his works in the realm of auteur cinema, especially after Annie Hall (1977), which marks a transition to more complex narrative structures and profound themes – the film was immediately followed by Interiors (1978), Allen’s first incursion into the domain of drama. At the same time, the director’s experiences as a gag writer for columnists and television comedians, and as a stand-up comedian both on stage and on TV, charge his auteur identity with elements of popular culture that for long existed in tension with auteur attributes, and which, as I explain later, largely precipitated the skepticism towards Allen as a serious filmmaker among American critics.

It is tempting to detect a transition, in Allen’s career, from the realm of popular comedies to that of auteur cinema; in other words, from the slapstick, the burlesque, and the one-liner to more “serious” philosophical themes dealing with death, God, adultery, and the self. Even when avoiding the risks of such clear-cut distinctions, studies of the director’s work tend to draw attention to the artistry or the political and cultural relevance of Allen’s humor. Maurice Yacowar’s introduction to Loser Take All: The Comic Art of Woody Allen (1979) is tellingly titled “The Serious Business of Comedy.” Sam Girgus’s The Films of Woody Allen (1993) and Robert Stam’s study of Stardust Memories (1980) and Zelig (1983) in Subversive Pleasures (1989) bring to light the complexity and theoretical dimensions of his oeuvre. Peter J. Bailey’s The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen (2001) analyzes the director’s cinematic dramatization of creative processes and anxiety about his place between art and entertainment. Mark T. Conard and Aeon J. Skoble’s Woody Allen and Philosophy: You Mean My Whole Fallacy Is Wrong? (2004) explores the philosophical undertones of his movies, thereby stressing their artistic value.

What I here hope to contribute to these and other studies of Woody Allen’s films is the investigation not so much of the artistic merits or the philosophical relevance of his comedy, but the coexistence, in Allen’s image, of the stand-up comedian with the ambitious artist, as he combines fleeting comments on current affairs with timeless metaphysical questions. This discussion calls for a brief account of the role of the cinematic author in the critical debates about the place of film in American culture, as they imply the interdependency between artistry and individual authorship. This overview will ground my analysis of the ways in which Allen embodies this tension, which in turn destabilizes traditional approaches to the auteur, and indeed adds a new dimension to this figure. I will subsequently look at the director’s topical treatment of cultural debates, the residual traces of his stand-up persona, and its implications for the problematic opposition between auteur and popular cinema.

The Place of the Auteur in American Film Culture

If in its romantic formulation the auteur is defined by the enduring and universal aspects of her work, Allen offers us a different model, defined as much by perpetual themes and elements of style as by the treatment of topical issues – in other words, current events in American culture, from politics to the mores of everyday life. And whereas Allen’s recurring themes and stylistic tropes place the director in the realm of auteur cinema, his exceptional productivity (at least one film per year since 1971), the usually limited budgets of his films and their constant recycling of similar material attach to Allen’s productions the seriality that is typical of popular culture. Allen personally articulates some of the tensions that have permeated the designation of the place and value of film in American society: tensions between uniqueness and repetition, universalism and topicality, and auteurism and commercialism.

The auteur has traditionally embodied notions of individuality, originality, control, stability, and universality. Primarily a tool for Cahiers du cinéma critics to assert the artistic value of supposedly “low” Hollywood genres, the notion of a film auteur was nonetheless at odds with the defining attributes of popular culture, characterized by its repetitive, ephemeral, and consumable qualities. Rather than fully embracing these notions, the defense of Hollywood filmmakers by the Young Turks headed by François Truffaut proceeded by attributing to their works characteristics associated with the high arts. One of the clearest articulations of this tendency was Jean-Luc Godard’s assertion that a film by Hitchcock was as important as a book by Aragon (MacCabe 2003: 74).1 The auteur thus embodies some of the oppositions that have marked the cultural production of the twentieth century at large. After all, the redefinition of art by the avant-garde was contemporary with, and partly motivated by, the advent of the cinema. The same notions of uniqueness, essence, timelessness, and universalism that defined the romantic artist were put into question when the attention to popular culture led to the validation of seriality, surface, transience, and topicality, especially in the writings of art and film critic Lawrence Alloway, as Peter Stanfield’s study of his work makes very clear (Stanfield 2008). Surrealist automatism, Dadaist ready-mades, and, later, Andy Warhol’s appropriation of rejects of consumerist society, were on a par with the meditations on the cultural value of objects industrially produced, with strong entertainment and mass appeal, and which displayed a so-called distasteful penchant for vulgar humor, physicality, and violence.

The earlier romantic vision of the auteur as the artist who survives the system, who is constrained by the industry’s political and commercial interests and yet is able to assert personal vision and style, was soon called into question, and was deeply impacted by the late 1960s structuralist turn in film studies. Untouchable for its transcending genius but challenged on the aforementioned attributes, this figure was quickly redefined as a theoretical construct, especially in the works of British film scholars like Geoffrey Nowell-Smith, Stephen Heath, Ben Brewster, and Peter Wollen, who coined the term “auteur structuralism.”2 This new account of auteurism replaced the biographical auteur with a set of “structures” – rather than human beings with specific worldviews, auteurs become “names for certain regularities in textual organization,” as Dudley Andrew explains in “The unauthorized auteur today” (2000: 21). “Auteur analysis,” Wollen argues in the foundational Signs and Meanings in the Cinema,

does not consist of retracing a film to its origins, to its creative source. It consists of tracing a structure (not a message) within the work, which can then post factum be assigned to an individual, the director, on empirical grounds (1972: 167–168).

The critic’s mission, in Andrew’s later rendition of Wollen’s theory, is to isolate “the auteur’s voice within the noise of the text” (2000: 21). It follows that, however skeptical about the possibility of locating the source of meaning on a self-expressing individual, auteur structuralism held on to romantic notions of uniqueness and permanence.

Given the industrial modes of Hollywood productions, it is not surprising that the attribution of traditional artistic values to cinematic texts was deemed either implausible or artificially imposed. Histories of American film criticism by Raymond J. Haberski (It’s Only a Movie! Film and Critics in American Culture, 2001) and Greg Taylor (Artists in the Audience: Cults, Camp, and American Film Criticism, 1999), for example, tell us about the movie-loving critics’ resistance to the standards applied to literature, the theater, or the fine arts. The excitement around cinema consisted precisely of the ways it begged the redefinition of cultural values, the novelty of a medium that, in Haberski’s words, was “both an industry and a cultural expression,” or an “art that had mass appeal and was mass produced” (2001: 11). Taylor’s account of the cult and camp criticism respectively practiced by Manny Farber and Parker Tyler since the 1940s shows that film’s collective and industrial production modes did not always accommodate a traditional understanding of authorship as identifiable and stable. On the contrary, these approaches privilege the critic’s, rather than the author’s, construction of meaning. Cult critics, Taylor explains, show little concern for the artistic impulse behind the making of films. Instead, these critics stress their own capacity to select objects that were either produced by Hollywood but had little merit or that simply lay outside of the industry. In Taylor’s words,

cult criticism focuses on the identification and isolation of marginal artworks, or aspects and qualities of marginal artworks, that (though sorely neglected by others) meet the critic’s privileged aesthetic criteria. Often the marginal cult object is not a traditional artwork at all but a select product of popular culture (1999: 15).

Cult critics elect obscure objects that escape commoditization, frequently promoting an “assault on the conventions and order of taste” (Taylor 1999: 32). Their goal is to reorient audiences’ choices, driving their attention away from traditional artistic standards, and towards “inappropriate objects from a lower taste culture” (32). These objects are to be given meaning and value by the critic, who guides audience’s likings, capacitating them to select and construe their own canons, “to define their own culture in opposition to prevailing standards” (33).

Similarly, camp criticism also seizes film for the critic’s own expressive needs. Where cult emphasizes selective criteria, “the critical camp spectator revels in the interpretation/transformation process while often placing little stake in the initial selection of mass objects” (Taylor 1999: 16). Inclined to investigations of psychological and archetypal manifestations, Tyler’s camp practices placed the critic at the origin of the film’s meaning, “the pleasure of criticism [lying] in forcibly remaking common culture into personal art” (16). Camp appreciation relies on “poorly controlled texts,” which prove “more rewarding than the tightly managed artwork” for a critic (and an audience) wishing to appropriate these texts for their own use (52).

The attribution of a subversive quality to cult and camp criticism presupposes an understanding of film as artistic expression that predates auteurism, in a narrative that opposes film-as-art and film-as-commerce, deprived of any cultural value. On the film-as-art front, James Agee, for one, privileged the director over screenwriters and actors; he spoke of geniuses, praised the artistic merits of Hollywood films, and advocated that a movie was as serious a cultural object as literature or painting. His review of Jean Vigo’s Zéro de Conduite (1933) and Atalante (1934) for The Nation on July 5, 1947, centered on the director’s artistry and, not unlike the politique des auteurs years later, detected a certain consistency in style. Historians call attention to Agee’s understanding of the director as “the deity behind the entire production, the father-progenitor of the film,” or the equivalent of “a symphony conductor, who ‘selects and blends his instruments’ to achieve aesthetic results” (Seib 1968: 123). Agee’s attribution of artistic merits to films often took the form of analogies with the high arts – he wrote, for example, that Preston Sturges’s The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1934) displayed the nihilism of Céline and the humanism of Dickens. Agee praised the film’s shifts between realism and comedy, claiming that, “if you accept that principle in Joyce or Picasso, you will examine with interest how brilliantly it can be applied in moving pictures and how equally promising” (reprinted in Agee 1958: 75).

The import of French auteurism by Andrew Sarris in the early 1960s, famously articulated in “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962,” blends Agee’s emphasis on directors with a cultist celebration of Hollywood as privileged site for the manifestation of auteurship. Pauline Kael’s merciless attack on the purportedly “esoteric” critical criteria proposed by Sarris (namely, technical competence, personal style, and interior meaning) contests, among other things, his biased preference for Hollywood movies. Kael criticizes Sarris for establishing that the director’s personality arises from a tension between artist and modes of production. He proposes, for example, that George Cukor’s “abstract style” is “more developed” than that of Ingmar Bergman, “who is free to develop his own scripts” (Sarris qtd. in Kael 1963: 18). In Kael’s words, Sarris’s ideal auteur

is the man who signs a long-term contract, directs any script that is handed to him, and expresses himself by shoving bits of style up the crevasses of the plots. If his “style” is in conflict with the story line or subject matter, so much the better – more chance for tension (Kael 1963: 17).

Curiously, the distinction between commercial and art films in the United States led to a territorial division where “art” became the domain of foreign productions – something suggested in the comparison between Cukor and Bergman. Stam also indicates the presence of a territorial component to Sarris’s criticism, claiming that his open defense of Hollywood productions ultimately evolved to a “surreptitiously nationalist instrument for asserting the superiority of American cinema” (Stam 2000: 89).

Allen himself seems to incorporate the binary opposing art to American filmmaking. While on the one hand his long lasting dismissal of the studio system and love of art cinema have posited him as “foreign” (Baxter 1998: 3), on the other he has stated that, being an American, his films would never be perceived as art in the United States (Lax 1991: 179). This displacement of American cinema within the terrain of the art film is ironic when one takes into consideration that Hollywood movies provided the material for the French formulation of the artistry of mise-en-scène – just as it was the attitudes of Orson Welles, Jonas Mekas, or John Cassavetes that legitimized the director as the key creator in spite of the collaboration of other professionals. Concurrently, the European auteurs that came to define the notion of “art cinema” had great impact on American filmmakers. The New American Cinema promoted by Mekas, for one, was modeled after European films (Taylor 1999: 87), and the recognizable styles of Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, and Brian De Palma, among others, owe as much to the aesthetic consistency of classical Hollywood auteurs as to the self-reflexive meditations typical of the French New Wave. However, few US directors have so explicitly articulated the split between the admiration for European art cinema and the American commitment to entertainment as Woody Allen.

Though the director’s recurring themes, stylistic tropes, and self-reflexivity define him as an auteur, Allen can just as easily be associated with Charles Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Jerry Lewis, or Mel Brooks. The unchanging characteristics of their performances intermittently produce the suspension of the illusion of fiction – rather than blending into the depicted worlds and disappearing into different characters, these actor-directors evoke both their roles in previous films and their public personas. Similarly, the parts played by Allen share very similar traits – the Jewish background, the unglamorous Brooklyn childhood, the conflicted relationship with psychoanalysis, the attraction to sexy and neurotic women, the love of jazz and of the movies. His trademark black-rimmed glasses and balding disheveled head lead to the perception of such characters as the same figure inhabiting different scenarios – blending in well in the universe of contemporary Manhattan writers or filmmakers, but standing out in scenarios such as the year 2173 in Sleeper (1973), nineteenth-century Russia in Love and Death (1975), or medieval England in Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex . . . But Were Afraid to Ask (1972).

Allen’s combination of European art cinema’s self-reflexivity and an all-too-New-Yorker avant-gardism epitomizes at once the intertextual patchwork that marks the citational cinema of the French New Wave and the tension between high and low cultures that guided the debate about the artistic status of film in the United States. The coexistence between popular art forms (slapstick, burlesque, stand-up) and high culture (Shakespeare, Dostoevsky, Bergman), and the artistic crisis experienced by some of Allen’s characters articulate and dramatize American cinema’s identity crisis, and the evocation of his stand-up persona allows for a topicality that exists in tension with the traditional conception of the auteur.

The Auteur as Commentator

Articles on Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep (1977) often quote Michael Tolkin’s observation that, “If [it] were an Italian film from 1953, we would have every scene memorized” (qtd. in Kim 2003: epigraph). Given that Burnett is an African American director, Tolkin’s provocative remark seems to address US racial politics. Yet it also attests to the ghettoization of American art cinema (often equated with auteur cinema), suggesting that art remains the exclusive reserve of foreign productions. The polarity art/entertainment ingrained in the debates about film in the United States is also a central trope both in Allen’s oeuvre and in his public discourse. Allen has incorporated the territorial marker of this distinction by endorsing the association of art cinema and Europe (heralding Ingmar Bergman and Federico Fellini) while linking American cinema to entertainment (celebrating the influence of the Marx Brothers and Bob Hope in his work). Hollywood Ending (2002) uses that opposition as a central element of the plot, with Allen’s character (Val Waxman) as a once successful director whose decadence is frequently described in terms of his pretentious insistence on being an “American artist.” The film makes nostalgic references to the long gone respect for the art of filmmaking, when access to foreign movies on New York’s screens was easier. Symptomatically, Waxman wants a foreign cinematographer to bring in some “texture” to the image, and ends up having a picture he directs blind (and which flops badly at the American box office) hailed as a masterpiece in Paris. The fact that the French are in reality more at ease with Allen’s auteur status than are Americans constitutes this narrative event as at once redemptive of Allen’s artistic status (however disdained at home) and mocking of the Europeans’ aesthetic tastes – a paradox that seems to haunt Allen’s own cinematic self-perception. Hence Hollywood Ending reworks the opposition between American popular movies and foreign art cinema incorporated in Allen’s public discourse about his work. Speaking to biographer Eric Lax in the late 1980s about the contrast between his early “commercial” comedies and his more dramatic films, Allen said,

There is a problem in self-definition and public perception of me. I’m an art-film maker, but not really. I had years of doing commercial comedies, although they were never really commercial . . . First there was a perception of me as a comedian doing those comic films, and then it changed to someone making upgraded commercial films like Annie Hall and Manhattan. And as I tried to branch off and make more offbeat films, I’ve put myself in the area of kind of doing art films – but they’re not perceived as art films because I’m a local person, I’m an American, and I’ve been known for years as a commercial entity . . . What I should be doing is either just funny commercial films, comedies and political satires that everybody looks forward to and loves and laughs at, or art films. But I’m sort of in the middle” (Lax 1991: 197).

In 1996, Allen told John Lahr: “The only thing standing between me and greatness is me . . . I would love to do a great film” (qtd. in Bailey 2001: 176). Similarly, Lax’s biography includes Allen’s statement about a purported inability to dwell on the “serious” and profound themes associated with the art film: “I’m forever struggling to deepen myself and take a more profound path, but what comes easiest to me is light entertainment. I’m more comfortable with the shallower stuff” (qtd. in Bailey 2001: 177). Allen’s statements, which are indicative of his typically self-deprecating style, echo his Stardust Memories character’s existential crisis – Sandy Bates’s shift from directing comedy to dramatic and artistically ambitious films is immediately rejected by critics and audience alike (Stardust comes out two years after Interiors, Allen’s first venture into drama).

The binary art/entertainment provides constant material for conflicts experienced by many of the writers and directors Allen plays in his films. As Bailey notes in The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen, these characters struggle to maintain some artistic integrity, resisting, when possible, the temptation to compromise their art for financial necessity (2001: 60). Alvy Singer (Annie Hall) and Isaac Davis (Manhattan, 1979) abandon television shows for more “serious” writing (theater and literature, respectively). Sandy Bates (Stardust Memories) struggles to have his “ambitious” films accepted by producers and studio executives, and Mickey Sachs (Hannah and Her Sisters, 1986) abandons a stable job as a TV producer when a brain tumor scare makes him reevaluate the meaning of life. Conversely, Cliff Stern (Crimes and Misdemeanors, 1989) undertakes the commission to direct a documentary on his commercially successful brother-in-law (Alan Alda), whose films he despises, in order to fight bankruptcy and artistic isolation, and Hollywood Ending’s Val Waxman reluctantly commits himself to directing a movie for his ex-wife’s husband, a studio tycoon.

The opposition low/high art also offers comic material for couple dynamics in Allen’s plots. Alvy and Isaac initiate Annie (Diane Keaton) and Tracy (Mariel Hemingway) into intellectual life (philosophy, literature, and classical and/or art cinema). Manhattan Murder Mystery (1993) and Mighty Aphrodite (1995), on the other hand, show the Allen characters’ enthusiasm about the popular confronted by their wives’ more sophisticated tastes – in Manhattan Murder Mystery, Larry loves basketball while his wife (Keaton) loves the opera, and in Mighty Aphrodite Lenny’s admiration for the Marx Brothers and jazz (he wants to name their adopted kid Groucho, Django, or Thelonious) contrasts with the passion of his gallery-owner wife (Helena Bonham Carter) for the fine arts. The husband/wife polarization of low/high art is taken to extremes in Small Time Crooks (2000), where Frenchy (Tracey Ullman) and Ray (Allen) become estranged when he refuses to be educated on high society’s artistic tastes. While Frenchy, accidentally turned into a millionaire, visits museums and reads the classics, Ray eats popcorn and watches old movies on TV.

Whereas on the levels of character and of Allen’s self-definition as an artist the binary high and low comes across as conflicted and hard to reconcile, on the aesthetic level it constitutes the director’s personal signature. Allen’s uniqueness lies obviously not just in the blending of what has conventionally been associated with the popular and the auteurist in film (which for that matter characterizes the works of directors like Godard), but in the components of this mix. Quotes (a trademark of auteurs like Godard, De Palma, or Quentin Tarantino, among others) have always permeated Allen’s career, and reflect his eclectic tastes. Citations include tributes to specific artists (Fellini, Bergman, Kubrick, Eisenstein, the Marx Brothers, Shakespeare, Dostoevsky), films (8 ½ in Stardust Memories; Amarcord in Radio Days, 1987; Autumn Sonata in September, 1987; M in Shadows and Fog, 1991; Rear Window in Manhattan Murder Mystery), literary texts (by Shakespeare in A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy, 1982; by Dostoevsky in Crimes and Misdemeanors), visual imagery (the futuristic scenario of 2001 and the orgasm machine of THX 1138 in Sleeper; the raising lion of Battleship Potemkin in Love and Death; the hanging clothes of M in Shadows and Fog) or specific film scenes (the mirror sequence of Lady from Shanghai in Manhattan Murder Mystery). The coexistence between literature and Freudian psychoanalysis, on the one hand, and slapstick, screwball, and stand-up comedy on the other, is one of the elements attuning the director with the art/entertainment tension that was central in the definition of an American film culture. But it is also through Allen’s signature use of one of these popular modes – namely stand-up comedy – that the director performs sociocultural commentary, adding a topical component to his films.

When considering Allen’s combination of the popular with the topical, it is worth remembering that he was once a freelance gag writer for newspaper columnists and TV performers, and that before entering the realm of cinema (and soon thereafter of auteur cinema), the director was himself a stand-up comedian on both the stage and television.3 As we know, stand-up comedy is largely a vehicle for sociopolitical and cultural commentary – from jokes about current events, politicians, and celebrities to comments on the mores of everyday life (traffic, public restrooms, eating habits, etc.). In fact, stand-up comics tend to be less concerned about constructing an altogether fictional world than telling anecdotes as if they had happened in real life – irrespective of how exaggerated or implausible their stories may be. More often than not, these comics appear under their own public identity (as Woody Allen, Chris Rock, or Jo Brand). However fictive their tales, they are narrated by the artist’s public (and highly performative) persona. Any traditional sense of a psychologically complex and consistent character is blurred with the artist’s autobiography. This is more apparent when the stand-up comic is also a film or sitcom actor (as with Allen, Rock, Jerry Seinfeld, or Larry David), rather than simply verbally reporting experiences to an audience, either on a stage or on a television screen.

What I am here suggesting is that the topical quality of Allen’s films results largely from the fact that his scripts and screen performances bear traces of his experience as a stand-up comedian. His appearance as a master of ceremonies for the New Year TV special Woody Allen Looks at 1967 provides a clear example. The program was part of NBC’s variety show The Kraft Music Hall, whose radio versions had been hosted by “king of jazz” Paul Whiteman and Bing Crosby, among others. As its title suggests, the program features Allen’s comments on the social, cultural, and political events of that year, both through stand-up routines and sketches. Allen’s overview of 1967 ranges from political satire to lifestyle – Allen and Liza Minnelli share the stage in a sketch about a husband complaining about his wife’s mini-skirt, and the program includes a spoof of Bonnie & Clyde, released that year. But it is in Allen’s stand-up monologues and in a Q&A with newspaper columnist and TV host William F. Buckley Jr. that we find the genesis of the personality and worldviews of his film characters. The aversion to social gatherings we see in Alvy’s distaste for parties in Annie Hall, where he chooses a basketball game over conversation with intellectuals of Commentary magazine, or the skepticism towards political action in Sandy’s shocked reaction to his French girlfriend’s account of her militant experience in May 1968 (Stardust Memories), can be traced back to jokes told in the Kraft special opening monologue. In a stand-up routine, Allen conveys his disbelief in the possibility of any group’s self-entitled nonviolence, the proof being he was “beaten up by Quakers.” Allen’s strong sense of not belonging is further dramatized in his joke about trying to help a “negro” kid (this is 1967!) from a beating and generating widespread anger – he is accused of being a fake liberal by the kid, a real liberal by the abusers, a fascist by the real liberals, a hippie by the police, and an anti-Semite by his mother. Allen’s typically self-deprecating Jewish humor manifests itself also in the previously mentioned Q&A with Buckley. Asked by a member of the audience if Israel should give their land back to the Palestinians, Allen answers, “No, I think they should sell it back.” It follows that Allen brings to his films the humor, persona, and worldviews he represented on the stages of variety theaters and television – both of which bear the stamp of popular entertainment.

The topicality of Allen’s jokes and sketches brings, in addition, a sense of immediacy to the comedy, which, as Oliver Double (2005) explains in his book on the genre, Tony Allen defines as stand-up’s “now” agenda. Referring to the importance of being attuned to the reactions of an audience in a theater, Double notes that, “straight drama shows events from another place and another time, but with standup the events happen right here in the venue” (2005: 173). This connection with the here-and-now for the audience invites an analogy with the topicality of Allen’s gags in his movies. Annie Hall features jokes about JFK’s assassination, Nazis, Commentary magazine, Poland’s political past (“[my grandmother] was too busy being raped by Cossacks”), and contemporary values (“everything your parents said was good is bad: sun, milk, red meat, college”). Topical jokes about the National Rifle Association in Sleeper (“a group that helped criminals get guns so they could shoot citizens; it was a public service”), or the postwar connotations of Wagner’s music in Manhattan Murder Mystery (“I start getting the urge to conquer Poland”) are, likewise, constant reminders of the here-and-now of our existences. The examples of references to elements of contemporary American society are numerous. In Curse of the Jade Scorpion (2001), Allen’s insurance investigator manifests his insecurity towards a strong female character (Helen Hunt) by observing that “she graduated from Vassar and I went to driving school.” Waxman’s aforementioned desire for filmic “texture” reflects the digital era nostalgia for the celluloid, and he is given an NYU business student to act as an interpreter for his Chinese cinematographer. Hollywood Ending’s criticism of current-day Hollywood comes also in the form of an absurd lifetime achievement award to Haley Joel Osmont (who was age 14 when the film came out). In Anything Else (2003), Dobel (Allen) complains that dialing 911 is like trying to get a mortgage. More recently, Allen’s surrogate, Larry David, opens Whatever Works (2009) with a monologue to the camera about the superfluous lives of the socially privileged, with their “nine servings of fruit and vegetables a day,” their “Omega 3, and the treadmill, and the cardiogram, and the mammogram, and the pelvic sonogram, and oh my god, the colonoscopy,” asking, “and what do you do, you read about some massacre in Darfur or some school bus gets blown up and you go, oh my god the horror, and then you turn the page and finish your eggs from the free-range chicken.”

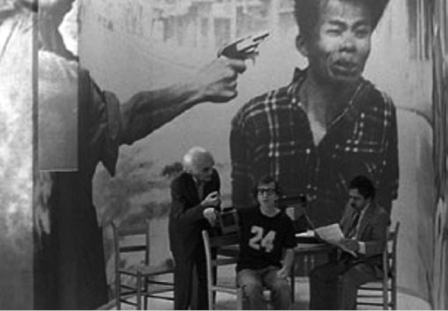

Annie Hall’s famous Marshall McLuhan scene is one of the clearest examples of the narrative’s invasion by the topical: Allen’s character pulls the media theorist from behind a film poster and into the scene to support his argument against an arrogant Columbia University professor pontificating in a movie theater – about none other than Fellini, one of Allen’s art-film heroes (Figure 1.1). McLuhan’s appearance anticipates the more consistent and extreme incorporation of real-life figures into the fiction in Zelig’s mockumentary-fashioned interviews with intellectuals like Susan Sontag, Saul Bellow, Irving Howe, Bruno Bettelheim, and John Morton Blum, who elaborate on the fictive Zelig, briefly metamorphosing into imagined versions of themselves – Blum, for example, is credited as the author of Interpreting Zelig.4 Most strikingly, Allen incorporates documentary footage of his own appearance in The Dick Cavett Show into the flashbacks explaining Alvy’s character at the beginning of Annie Hall (Bailey 2001: 59).

The references to topical issues define the characters played by Allen not so much as psychologically consistent beings enclosed within the narrative, but as commentators expressing their views by means of jokes. In relation to the question of topicality, it is through stand-up that Allen becomes an outsider to the worlds depicted in his narratives, to the classical conception of a self-enclosed diegesis, and to the realm of auteur cinema. The stand-up mode facilitates the penetration of the film by the extrafilmic, momentarily causing what in Carnal Thoughts Vivian Sobchack, speaking of the presence of documentary elements in fictional narratives, defines as the restructuring of the fiction as the space of the real (Sobchack 2004: 277).5 It is through Allen’s comments on current affairs that his films become topical, complicating the conception of the auteur as transcendental – notwithstanding the stylistic sophistication, universals, and profound matters singled out by scholars and critics in their legitimate task of illuminating Allen’s artistry. Allen’s self-conscious articulation of his own auteur identity tends to posit his affinities with popular forms of comedy as obstacles for the consolidation of his place in the pantheon of art film directors. The last segment of this chapter explores the fictional treatment given to this issue in Stardust Memories, where Allen voices the mores of American film culture through a fictionalized career examination questioning the director’s own auteur ambitions, as well as a cultural milieu’s response to the idea of artistry in film.

Stardust Memories: The Auteur between Distrust and Desire

At the beginning of this chapter, I argued that Woody Allen’s characters often articulate some of the questions that permeated the American debates about cinematic authorship – the validity of applying criteria such as artistic intention, control, and self-expression to assess the cultural value both of individual films and of cinema as a whole. The dramatization of Sandy Bates’s relations with fans and producers in Stardust Memories opens the way to a career examination that includes Allen’s own artistic anxieties (however fictionalized), meditations about the opposition between high and low arts, and a caricature of American film culture, albeit one inflected by the Fellinian universe of 8½, which Stardust openly parodies in the black and white photography, the grotesque portrayal of cultural types, the childhood flashbacks, and the figure of the estranged and conflicted cineaste.

Allen’s fictionalized self-evaluation is rendered through the story of a comic filmmaker undergoing artistic and personal crisis. The framework for Sandy’s interior battles is a retrospective of his films, turned into a subjective journey that takes place at a time in which producers, disdainful of Sandy’s artistic ambitions (and fearful to put at risk a profitable and stable cinematic production), reject his first dramatic screenplay. The retrospective exposes the fictional director to confrontations with such producers, studio executives, and critics. Sandy’s desire to make a drama with “meaning” is also undermined by his fans, interested in nothing but good laughs. Standing for “self-expression,” “meaning” is at once dismissed and desired by Sandy, and reflects Allen’s own dubiety about the spiritual benefits of artistic creations – Bailey suggests that the film dramatizes “the rejection of the redemptive power of art” (2001: 89).

Stardust resorts to a series of Q&A sessions, scattered through the narrative, to establish a dialogue opposing Allen’s fictional filmmaker and a caricaturized audience of critics, fans, scholars, and museum curators. In his analysis of the film, Stam calls attention to a dynamics in which “Allen places in the mouths of various characters all the conceivable charges that might be leveled against Allen’s oeuvre in general and against Stardust Memories in particular” (1989: 196). Such a structure grants Allen the opportunity to perform the “anticipatory self-depreciation” found in Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground – in Stardust, says Stam, such a practice “consists in demonstrating [the director’s] advance knowledge of all possible criticisms of himself and his work” (197).

Stardust articulates this anticipated reaction to criticisms through the opposition between the “emptiness” of popular cinema and the “meaningfulness” of art cinema. On the one hand, Sandy contemptuously dismisses the spectators’ interrogations about his comedies’ textual meanings during the Q&A sessions: a serious question about what the director was trying to say in his movie is dismissed with a blunt “I was just trying to be funny.” On the other, the protagonist protests the rewriting of his dramatic screenplay by studio executives, showing dismay towards their interference with his artistic processes. Both the sessions and the meetings reveal the impossibility of dialogue between artist and audience, and between artist and studio executives. But most significantly for the implications of Allen’s affinities with popular comedy, Sandy’s comic talent is ambiguously rendered as an obstacle to his development as an artist, but also as a gift. Implying the traditional distinction between entertainment and art, a producer defiantly questions the director’s anxieties and ambitions: “What does he have to suffer about,” completing his sentence with a line that, having been written by Allen, works as a form of self-consolation: “Doesn’t the man know he has the greatest gift that anyone can have – the gift of laughter?” Such criticisms of Sandy’s desire to make a personal movie were ironically echoed in the critical reception of Stardust. The titles of the reviews of the film, listed by Stam in his analysis, betray the critics’ dismissive attitude towards the director’s homage to his auteur-cinema “model,” which in turn read as a dismissal of his incursion into the terrain of artistic seriousness associated with European cinema: “Woody doesn’t rhyme with Federico” (Sarris), “Inferiors Woody Allen hides behind Fellini” (Schiff), and “Woody’s 8 wrongs” (Shalit) (Stam 1989: 197).

Stardust is also a vehicle for Allen to respond to some of the criticism addressed to his work – for example, his allegedly apolitical stance, noted by a fictional audience member who asks where Sandy stands politically. The hero’s answer – “I’m for total honest democracy, and I also believe the American system can work” – perpetuates Allen’s own scattered mode of political commentary. Similarly, Sandy’s contention that Bicycle Thieves is not exclusively a social film equally reveals Allen’s awareness that his movies are perceived as lacking social commentary, often unfairly. After all, he has produced elaborate caricatures of social types, which can be found in the naivety and hypocrisy found in Los Angeles (Annie Hall) and among the New York intelligentsia (Annie Hall, Manhattan, Stardust, Hannah, Husbands and Wives, 1992, Whatever Works, among others); the Italian American who recognizes Alvy Singer in the streets; the lower class, Brooklyn Jewish origin of all of Allen’s characters; and the elite’s extreme measures to secure their social status, as in the killing of lovers by a wealthy doctor (Martin Landau) in Crimes and Misdemeanors and a social-climbing tennis instructor (Jonathan Rhys Meyers) in Match Point (2005).

Though fighting for the expression of his subjectivity, telling producers one cannot be funny when surrounded by “human suffering” (Figure 1.2), Sandy nonetheless embodies the artist’s contradictory desire to both reveal and hide his soul, to both expose his interiority and seal it to public admission. For in Stardust the access to the artist’s intentions equals the access to his private life. The interpretation of the symbolism in Sandy’s films takes the form of psychoanalysis – in a dream sequence depicting a posthumous tribute, Sandy’s psychoanalyst confabulates on how the director’s films reflect his incapacity to “block out the terrible truths of existence,” speaking of Sandy’s inability to integrate the world of show business when Hollywood believes that “too much reality is not what the people want.” Similarly, the artist’s expression is repeatedly transformed into a tool for a threateningly obsessed audience to assess Sandy’s personal life, inquiring into his narcissism and sexual practices (“Have you ever had intercourse with any type of animal?”), and speculating about Sandy’s search for the meaning of life.

Further qualifying Stardust as an oblique form of self-examination is the confusion between the real artist and his screen persona, something that Allen experiences in real life. The film offers plenty of material for the conflation between Sandy and Allen. His character’s career move reflects the director’s own desire to incorporate drama into his practices – he had recently directed the Bergmanesque Interiors, which was followed by the dark tones of September, Another Woman, and, much later, Match Point and Cassandra’s Dream (2007), as well as by the blending of the dramatic and the comedic in The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985), Hannah and Her Sisters, Crimes and Misdemeanors, Husbands and Wives, or Melinda and Melinda (2004). John Baxter describes how, after watching The Seventh Seal and Cries and Whispers, Allen said that seeing Bergman’s films made him reevaluate his own work (1998: 278), which echoes in Sandy’s decision to write “meaningful” screenplays.

Examples of the confusion between Allen and his characters proliferate in the critical reception of his movies, and are frequently discussed in the literature on the director (including studies by Nancy Pogel, Girgus, and Bailey, as well as the biographies by Baxter and Lax). A 1992 issue of New York magazine dedicated two articles to pointing out similarities between the plot of Husbands and Wives and Allen’s personal life,6 which at the time was a public scandal. Gabe, Allen’s character in the film – a man who falls out of love with his wife (Farrow) and feels helplessly infatuated with a young student (Juliette Lewis) – was equated with the real Woody Allen, who at the time was ending his relationship with Farrow. David Denby, for one, read the film as autobiography:

When I saw Husbands and Wives, the audience, caught between loyalty and distaste, was clearly uncomfortable. So was I. Parts of the movie are excruciating – the scenes between Woody Allen and Mia Farrow, for instance, lack the minimal degree of illusion necessary to fiction . . . I felt like I was snooping (qtd. in Bailey 2001: 183).

Stardust also generated confusion, which according to Bailey much angered the director, who “impatiently rejected the imputation that Sandy Bates [was] himself and that his perceptions [were] unmediated versions of Allen’s values and feelings” (87). The director eventually comments on this kind of confusion in ironic statements to the press. In an interview about Deconstructing Harry, Allen told the New Yorker that the film was about a “nasty, shallow, superficial, sexually obsessed guy. I’m sure that everybody will think – I know this going in – that it’s me” (qtd. in Bailey 2001: 3). As Bailey’s book shows, the director also transposes this confusion to the domain of plot by exploring the problems that may arise when real events become material for art. Dianne Wiest’s character in Hannah and Her Sisters writes a script inspired by Hannah’s marriage. In Deconstructing Harry, Judy Davis accuses the protagonist (Allen) of not even bothering to disguise the details of their love affair in his book. Later on, Harry tells a professor about the character of his next novel: “It’s me thinly disguised. In fact, I don’t even think I should disguise it anymore . . . It’s me.” Allen himself had admitted to the autobiographical quality of his works in a 1972 interview:

Almost all my work is autobiographical – exaggerated but true. I’m not social. I don’t get an enormous input from the rest of the world. I wish I could get out, but I can’t (qtd. in Lax 1991: 179).

In Stardust, the confusion between real life and fiction also takes the form of the constant interference of the public into the private sphere. Fans wanting Sandy’s attention during the retrospective constantly interrupt his private conversations. The viewer can be never fully captured by the film’s romantic plot; the breaking of the news that Sandy’s lover left her husband and his own flirtations with a neurotic violinist are disrupted by the appearances of fans. Sandy’s personal life is constantly transformed into spectacle – from a surprise visit to his sister (witnessed by her yoga friends) to his first encounter with his lover’s children (under the eyes of a restaurant’s customers).

In addition to involuntarily generating curiosity, Sandy is perceived as a reassuring presence – yet another element inspired by the director’s own experiences. Baxter’s biography informs us that, knowing that Allen would not talk to strangers, some fans have “ask[ed] if they could walk a few blocks with him in silence, feeling themselves comforted in his presence” (1998: 278). Similarly, the fictional audience represented in Stardust is as interested in knowing Sandy’s inner motivations as they are in exposing their own intimacies to the filmmaker. Stardust inverts the dynamics between artist and audience by having the spectators confide in the auteur, subverting the romantic model criticized by Barthes in “The Death of the Author” (1981) (yet perhaps suggested by the conception of a reader yearning for the writer in The Pleasure of the Text). In the film, a fan approaches Sandy to tell him he was a Cesarean; another asks him to write an autograph to his wife calling her an “unfaithful lying bitch.” A young man wants Sandy to take note of his name because people say they resemble each other; a screenwriter wannabe wants him to hear his idea for a comic film. An aspiring actor wastes Sandy’s time showing and discussing his portfolio with him. A young woman shows up in his hotel room wanting to make love. A former schoolmate, now a cab driver, stalks the director to talk about the unfairness of life, contrasting Sandy’s glories with the dullness of his existence. Another man wants Sandy to film his amateur screenplay, and several representatives of charitable associations solicit Sandy’s contributions to and presence at special events.

Part of the hostility depicted in Stardust lies in the fans’ polarized attitudes of not seeing Sandy’s need for privacy and desperately wishing to be seen by him – in other words, in Allen’s portrayal of celebrity culture. The lack of empathy between artist and audience is also manifested in the opposites of not seeing and seeing too much, in refusing to understand the director’s artistic ambitions while comically trying to find symbolism where there is none – asked to interpret the significance of the protagonist’s Rolls Royce, a spectator pompously replies that he sees it as “his car.” Allen’s conflicted relationship with his audience was expressed in a 1992 interview, where he stated that, contrary to what critics said about the public’s indifference to his work, it was he who had no concern for the viewers’ needs:

The backlash really started when I did Stardust Memories. People were outraged. I still think that’s one of the best films I’ve ever made. I was just trying to make what I wanted, not what people wanted me to make (qtd. in Baxter 1998: 290).

Stardust’s discussion of authorial expression revisits the debates about critical authority and lack of artistic control that have marked the American approach to film authorship since the 1940s. The controversy surrounding the possibility of artistic expression within a collective and industrial structure is articulated in the distinction between entertainment and art made by the producers and studio executives depicted in Stardust; they see Sandy’s incursions into existential crisis as self-indulgent, including him in the hall of filmmakers who, in the words of a producer, “try to document their private suffering and fob it off as art.” The artist’s loss of control lies partly in the meddling with the director’s career paths, with producers, critics, and the general audience protesting against Sandy’s desire to abandon the commercial production of comedies. Similarly, the constant harassment – the public invasion of the director’s private sphere – indicates the artist’s loss of control over his personal life.7 Public and private are intertwined by the parallel between lack of artistic freedom and lack of privacy, between Sandy’s concern with the integrity of his screenplay and his yearning for solitude.

Equally attuned with some of the debates that evolved around the film author in the United States is the satirizing of the audience’s curiosities about Sandy’s aspirations, calling to mind Barthes’ dictate that readers shall investigate the work rather than the man (1981: 209), which in turn echoes the dismissal of authorial intention found in the creative critical writings of Manny Farber or Parker Tyler. Sandy’s incorporation of the European auteur model finds resistance in the show business framework in which he operates. Yet his satirical answers about the meaning of some of his films, chief among which is “I just wanted to be funny,” aligns him with the skepticism of those critical trends which, with Pauline Kael, feared that the transformation of movies into an object for intellectual scrutiny would deprive them of their popular appeal8 – trends that, according to Stardust, may nonetheless be harmful for the director’s artistic development. The very enthusiasm about film is ridiculed in a scene where a fan asks about a possible homage to Boris Karloff and then blinks at the camera to comment on his own cinephilic erudition. Allen, however, partakes of this enthusiasm – not only does the director frequently invoke his love for Hollywood movies during his childhood, film viewing is a constant in his oeuvre – Play It Again, Sam (1972), Annie Hall, Manhattan, Crimes and Misdemeanors, and Hollywood Ending are some of the movies featuring the director in the role of a cinephile. Most importantly, Allen’s love of film is evident in the abundance of intertextual references that mark his personal style. Such a mockery is therefore a form of self-mockery – the very tribute that Stardust pays to 8 ½ is satirized when Sandy’s actor tells the aforementioned film buff that the movie was not an “homage” to Karloff: “we just stole the idea outright.”

Allen’s topical comments on politics, lifestyle, aesthetic fashions, and American debates about film destabilize the notion of the auteur as producer of timeless works that transcend their eras. Yet, far from trying to undo the legitimization of Allen’s auteur status, I hoped to explore the ways in which the director’s experience in stand-up comedy has tainted his films with the modes of variety theatre and television, thereby adding a new dimension to his auteur identity. The idea of a topical auteur, a commentator on current affairs, challenges the romantic conception of film authorship and, by extension, the validity of relegating artistry to the exclusive domain of auteur cinema.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Peter Stanfield, Peter J. Bailey, and Sam Girgus for their comments on this chapter, and Heather Green for her treatment of the images.

Notes

1 Godard’s idea was later echoed in Peter Wollen’s contention, in Signs and Meanings in the Cinema, that “Hitchcock is at least as important an artist as, say, Scott Fitzgerald” (qtd. in Naremore 1990: 19).

2 For a collection of significant essays on the topic, see Caughie (1981).

3 The presence of stand-up comedy elements in Allen’s films is discussed in Sayad (2011).

4 In his analysis of the film in Subversive Pleasures, Stam (1989: 203) calls Blum’s association with the fictional book a type of “erroneous attribution.”

5 Sobchack analyzes the association between Allen’s real life and fictional narrative in Husbands and Wives in “The Charge of the Real: Embodied Knowledge and Cinematic Consciousness” (2004: 258–285).

6 See Hoban (1992) and Denby (1992).

7 Barbara Kopple’s documentary on the director (Wild Man Blues, 1997) provides an insight into Allen’s relationship with celebrity as she follows him on a European tour with his jazz band. The documentary registers a similar dynamics between fan and star as that found in Stardust Memories – where fans are eager for attention and the artist is more annoyed than he is appreciative.

8 See Kael (1995).

Works Cited

Agee, James (1958) Agee on Film: Volume One. New York: Perigee Books.

Andrew, Dudley (2000) “The unauthorized auteur today.” In Robert Stam and Toby Miller (eds.), Film and Theory: An Anthology. Oxford: Blackwell, 20–29.

Bailey, Peter J. (2001) The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky.

Barthes, Roland (1981) “The death of the author.” In John Caughie (ed.), Theories of Authorship: A Reader. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul in association with the British Film Institute, 208–213. (Original work published 1968.)

Baxter, John (1998) Woody Allen: A Biography. London: Harper Collins.

Caughie, John (ed.) (1981) Theories of Authorship: A Reader. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul in association with the British Film Institute.

Conard, Mark T. and Aeon J. Skoble (eds.) (2004) Woody Allen and Philosophy: You Mean My Whole Fallacy Is Wrong? Chicago: Open Court.

Denby, David (1992) “Imitation of life.” New York (Sept. 21), 60–62.

Double, Oliver (2005) Getting the Joke: The Inner Workings of Standup Comedy. London: Methuen.

Girgus, Sam B. (1993) The Films of Woody Allen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Haberski, Raymond, Jr. (2001) It’s Only a Movie! Films and Critics in American Culture. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky.

Hoban, Phoebe (1992) “Everything you always wanted to know about Woody and Mia (but were afraid to ask).” New York (Sept. 21), 32–42.

Kael, Pauline (1963). “Circles and squares.” Film Quarterly 16.3, 12–26.

Kael, Pauline (1995) “It’s only a movie.” Performing Arts Journal 17.2/3, The Arts and the University (May–Sept.), 8–19.

Kim, Nelson (2003) “Charles Burnett.” http://sensesofcinema.com/2003/great-directors/burnett/ (accessed Sept. 30, 2012).

Lax, Eric (1991) Woody Allen: A Biography. New York: Knopf.

MacCabe, Colin (2003) Godard: A Portrait of the Artist at Seventy. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Naremore, James (1990) “Authorship and the cultural politics of film criticism.” Film Quarterly 44.1, 14–23.

Pogel, Nancy (1987) Woody Allen. Boston: Twayne.

Sarris, Andrew (1962) “Notes on the auteur theory in 1962.” Film Culture 27, 1–8.

Sayad, Cecilia (2011) “The auteur as fool: Bakhtin, Barthes and the screen performances of Woody Allen and Jean-Luc Godard.” Journal of Film and Video 63.4, 21–34.

Seib, Kenneth (1968) James Agee: Promise and Fulfillment. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Sobchack, Vivian (2004) Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Stam, Robert (1989) Subversive Pleasures: Bakhtin, Cultural Criticism and Film. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

Stam, Robert (2000) “The author: Introduction.” In Robert Stam and Tobey Miller (eds.), Film Theory: An Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell, 1–6.

Stanfield, Peter (2008) “Maximum movies: Lawrence Alloway’s pop art film criticism.” Screen 49.2, 179–193.

Taylor, Greg (1999) Artists in the Audience: Cults, Camp, and American Film Criticism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Wollen, Peter (1972) Signs and Meaning in the Cinema, 3rd edn. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Yacowar, Maurice (1979) Loser Take All: The Comic Art of Woody Allen. New York: Frederick Ungar.