This chapter arrives on a decidedly postmodern trajectory, one where reflexivity1 is as much a practice of reading a film as it is a process of making one (Frus 2008: 57). It is influenced by my own experiences with films in general, and Woody Allen’s work in particular, over the last 35 or so years. It is steeped in heuristic inquiry,2 a process of discovery that acknowledges both the personal and creative dimensions of critical analysis. And, finally, this chapter will be by necessity “an” interpretation, not “the” interpretation, for, like the emerging genre of the “essay film” (Rascaroli 2008: 25), Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989) poses questions but offers no simple solutions, and is elusive and inconclusive. I offer these caveats as a framing device, for this discussion is as much about you, the reader, as it is about me, the writer. Unlike a typical Hollywood narrative that offers easy access but limited potential for interpretation, Crimes can be fairly impenetrable for all but those willing to do the spadework of interpretation – not unlike Eco’s classic “open text” (1979: 49). At the very least we need to actively meet this film, for it resists what Barthes would call passive viewing (1974: 4) and, like all reflexive works, Crimes and Misdemeanors demands engaged (or even imaginative) thinking (Stam 1985: 16).

Many of Allen’s films contain themes pertaining to morality and existential angst, and Crimes and Misdemeanors is no exception. Mark Roche sees competing philosophies of justice (2006: 269), Sander Lee places the film within Allen’s career-long investigation of the moral decline of society (2002: 139), and Mashey Bernstein suggests the film is a meditation on the nature of good and evil in a post-Holocaust world (1996: 227). For my part, however, in this chapter I am looking at how both main storylines can be seen as interlinked ruminations not only on the art and process of filmmaking, but also on the concept of story, the construction of the cinematic narrative, and the audience’s role in its interpretation and experiences. What is challenging is that all the strands are tightly woven into the film’s fabric, and no amount of tugging on any one individual thread holds the easy promise of a clean and complete unraveling.

In order to locate Allen’s efforts within the zeitgeist of postmodern filmmaking, we must accept the development and refinement of his reflexive tendencies as a natural outgrowth of his career as a stand-up comedian and author of comedic essays. I have argued elsewhere that Allen’s earliest public, professional persona is inextricably linked to his Jewish identity (Bachman 1996: 179). Although it is dangerous, if not foolhardy, to try to sum up all of Jewish humor (Whitfield 1986: 247), at its core is an intellectual tradition, steeped in cerebral manipulations that expose ironies and contradictions in a harsh and cruel world. It is a comedy of self-deprecating outcasts (Bleiweiss 1996: 203) that “raise(s) comedy-as-hostility and comedy as tragic catharsis to new levels and new expectations” (Cohen 1987: 9).

Allen’s “little man” persona, positioned as he is on the margins of society, affords him an opportunity to critique the mainstream norms and mores from the perch of an outsider, yet much of his humor depends on his location as an insider, albeit a poorly fitted one (Pogel 1987: 8). Laughter depends on the recognition of this self-consciousness (Yacowar 1979: 5), of the swinger or self-professed ladies’ man who enjoys so little success yet can’t seem to gain the perspective that he’s a loser at love, of the sophisticated intellectual who can’t even manage a relationship with his kitchen appliances. His comedy routines depend on the powers of disjunctive comparison, ironic Hegelian dialectics, born of competing visions – one rooted in traditional logic and the other whirling around in an almost surreal plane. The target audience is limited, however, to those who can appreciate, if not comprehend, the obscure references. This is captured beautifully in a starkly autobiographical moment in Annie Hall (1977) when Annie (Diane Keaton) enthusiastically responds to Alvy’s (Woody Allen) stand-up routine before a college audience, a routine cribbed directly from Woody Allen’s own stand-up catalogue. “I’m beginning to get the references . . .” Annie assures Alvy, who then warns her that the later show is layered with even more challenging material.

This understructure emerges more sharply in his comic writing, his “occasionals” that appear in periodicals such as The New Yorker and Esquire. Much of his humor depends on the reader’s at least nodding acquaintance with the foundational theories and critical processes of literature, philosophy, academia, art, or religion, which he then gently probes and critiques: “God is silent. . . . Now if man could only shut up” (Allen 1980: 5) or “Can we actually ‘know’ the universe? My God, it’s hard enough finding your way around Chinatown” (Allen 1971: 29). His critiques never appear to be withering or sharp; he pokes, he prods, he exposes possible flaws, he offers momentary delight and then opens the door, as only the best comedy can, to more serious consideration (Mast 1973: 15).

Allen’s comedic sensibilities seemed to have uniquely positioned him to take full advantage of the emerging freedom of expression employed by the bold cinematic experimenters in the 1960s, an era alive with artistic possibilities. Led by such daring young filmmakers as those of the French Nouvelle Vague, the classic cinema was under assault. The illusion of reality, the basic premise of the classic Hollywood narrative, arguably the dominant artistic mode of the twentieth century, was undermined by fresh takes on the tropes of genre and the conventions of the strict formalist lexicon that had shaped and informed the commercial medium for decades. Inspired by the likes of such visionaries as Resnais, Truffaut, and Godard, filmmakers became enmeshed in a dialogue on the very nature of motion pictures, transforming themselves into, as Godard observes, critics who made movies instead of just writing criticism (qtd. in Stam 1985: 17). Academia soon followed suit, creating grand theories of how movies make meaning, borrowing heavily from psychoanalysis and the literary fields.

Allen was apparently not immune to such heady machinations. From his first forays as a director, we can see an overt tendency to explore and exploit the cinematic medium. Take the Money and Run (1969) is a full-on assault on the tropes of the documentary, operating in (and perhaps helping to define) the parodic modality of the “mockumentary.” His next effort, Bananas (1971), has an almost manic reflexivity, pulling out all the stops in a tour-de-force send-up of media in the modern, electronic age. Even though such playful reflexivity can be dismissed as a mere superficial method of demystification (Stam 1985: 165), this does not preclude such efforts from the possibilities of more significant meanings. For example, a small moment with larger ramifications occurs in Bananas when Woody Allen’s character, Fielding Melish, receives an invitation to dine with the president of the small banana republic in which he finds himself. Melish lies back on his bed in a rhapsodic reverie, accompanied by the standard, nondiegetic harp music on the film’s soundtrack. Something attracts Melish’s attention, however, and we quickly realize it’s the music itself, whose narrative functionality is punctured when Melish throws open the closet door, exposing the source of the music, a harpist who apologizes, explaining that he has trouble finding a place in which to practice. Laughter ensues but, through reflection, Allen has made his point. He has literally “opened the door” to speculation on the narrative functions of nondiegetic music.

Throughout the 1970s and beyond, Allen continued to refine his use of reflexivity to the point that his audiences came more prepared to suspend belief rather than disbelief (Recchia 1991: 258). These films parody literary and filmic genres, bend time and space, and probe art and philosophy in increasingly skillful efforts, leading us to Crimes and Misdemeanors, which sits, conveniently as of this writing, at the midpoint of his filmmaking career.

There are two main plot lines in Crimes and Misdemeanors. The seemingly more serious story – and for the purposes of this chapter, the more traditional in the narrative sense – concerns Judah Rosenthal (Martin Landau), a successful ophthalmologist who engineers the murder of his mistress, Dolores “Del” Paley (Anjelica Huston) when she threatens to expose their affair and, potentially, his questionable financial moves. The seemingly “lighter” plot concerns Allen’s Cliff Stern, a small-time documentary filmmaker who loses both in love and in his art. Both plots can be approached as inquiries into the nature of the filmic experience. I arrive at this reading not only by way of his earlier works, but also by his utilization of the intertextual technique of inserting excerpts of old black-and-white feature films into the narrative flow. That all of the scenes come from mainstream studio releases of the Golden Age of Hollywood, with their neatly structured, unambiguous endings, clearly defined character arcs, and unmistakable moral structures is a point that should not be ignored. This consciously reflexive technique prompts the viewer to speculate on the idea of narratives, of stories, their interpretations and (re)telling, that permeates the entire film.

The first excerpt appears after the initial contentious scene between Judah and Del, centered on the letter she sent to Miriam (Claire Bloom), Judah’s wife, which he intercepted and subsequently destroyed. Tension and argument ensue and the scene ends with the two in an uncomfortable embrace as Judah sighs, “Oh, God.” This quiet moment is suddenly ruptured by the disorienting appearance of Ann (Carole Lombard) and David (Robert Montgomery) in an argument from Alfred Hitchcock’s RKO release Mr. and Mrs. Smith (1941), followed closely by the revelation that this is the movie which Cliff and his niece, Jenny (Jenny Nichols), are watching in a darkened theatre (Figure 8.1).

Figure 8.1 Cliff Stern and his niece Jenny watch one of the movies that provide an ironic counterpoint to the plots of Crimes and Misdemeanors.

(Producers: Robert Greenhut, Charles H. Joffe, Thomas A. Reilly, Helen Robin, Jack Rollins)

Although it’s an elegant answer, from a filmmaker’s perspective, to the question of how to transition from the Judah plot line to Cliff’s, it is a revealing choice nonetheless. There is a plethora of scholarly literature on Hitchcock, long the darling of academe.3 That Allen, who has a habit of delving into dialectics, would select a Hitchcock film, then, isn’t very surprising. But there is a very telling moment in this film that informs all that follows in Crimes, although it isn’t included in Allen’s film. Ann and David decide to have dinner at a restaurant they visited before they were married. The place and neighborhood have seen much better days, however, but they make the best of it, convincing the proprietor to allow them to dine out on the sidewalk. A group of children gather to watch them, and the couple decides to unnerve the kids by staring back at them. In a shot/reverse shot, both they and the children are seen staring not so much at one another, but at the camera and, by extension, directly at us in the audience. We watch and we’re being watched. We’re the ones who become, if not unnerved, then certainly aware of the voyeuristic experience, one that is not introduced without a certain element of risk (Howe 2008: 17). This is a technique that Hitchcock employs in several of his other films, and has served as an inspiration for a veritable cottage industry in academic circles utilizing psychoanalytic strategies to decipher his films.4

Of course, if we miss this connection (and I will be the first to admit that it took several screenings to come to this realization), we’re denied both the depth of the experience and the opportunity to wholly take part in the intertextual dialogue, but such is the strategy that Allen consistently employs, not only in these intertextual references, but also across the body of his work. If you care to engage in the dialogue, your experience is enriched; if not, you run the risk of being alienated from, or at best, limited to, a superficial experience of the entire enterprise. A perfect example occurs when Halley (Mia Farrow), upon first meeting Cliff, observes that he really doesn’t like Lester. Cliff responds, “I love him like a brother. David Greenglass.” I must confess that I had to dig to discover that David Greenglass was Ethel Rosenberg’s brother and had played an important (and questionable) part in her conviction. Armed with this information, the joke is apparent and funny, but I had to work to get there, not unlike Annie in her struggles to fully appreciate Alvy’s stand-up routines in Annie Hall or even, in the present case, of connecting Hitchcock’s Mr. and Mrs. Smith to Crimes.

Once this reflexive genie, inspired by the concept of watching, is out of the bottle, it’s difficult to put it back in. We’re encouraged to engage in the ongoing debate surrounding the abandonment of the “cloak of invisibility” taken for granted in the classic Hollywood narrative (Willemen 1986: 212) which then leads us to a reconsideration of Judah’s opening speech at the dinner given to honor his philanthropic efforts. Judah notes,

I remember my father telling me . . . the eyes of God are on us always . . . the eyes of God. What a phrase to a young boy. I mean what were God’s eyes like? Unimaginably penetrating, intense eyes, I assumed.

This scene can understandably be used as an introduction to the religious and moral themes of the film, but in this case I am suggesting that it also contains the seeds for the reflexive discourse. In the cinematic experience, it is the spectator who enjoys a certain Godlike, omniscient vantage point. We who watch in the audience can see not only what the characters see, but what they don’t see, as well. We are voyeurs, witnessing, with unimaginably penetrating eyes, subjective internal states as well as objective fly-on-the-wall points of view. This all-seeing, all-knowing privileged position, long the domain of the classic narrative structure, comes with an oddly quixotic entitlement – we are empowered to see, yet to do nothing in the face of the unfolding events. We are assured, however, within the strictures and demands of the classic Hollywood narrative, of a logical, and, if not happy, an invariably unambiguous conclusion – a point Allen will exploit within the narrative of Crimes.

We then must consider the other intertextual moments in the film, which are often counterpoints to the dramatic action and are at once comic but also no less revealing of what Bailey identifies as Allen’s “self-conscious reconfiguring of the relationship between the chaos of experience and the stabilizing, controlling capacities of aesthetic rendering” (2001: 5). For example, as Judah wrestles with and recoils from the terrible responsibility of engineering Del’s murder, we’re treated to an outtake from This Gun For Hire (Tuttle, 1942) in which Gates (Laird Cregar) doesn’t want to know the gory details of a planned murder. Tommy (Marc Lawrence) persists in telling him, calling it a “work of art.” It’s soon revealed that Cliff and Halley are watching the film, and Cliff whispers, “This only happens in the movies.” Cliff ironically, albeit unwittingly, refers not just to the movie on the screen but to Judah’s struggles as well.

At another point, after Del’s murder, hard on the heels of the revelation that a detective wants to talk with Judah, Cliff and Jenny watch a scene from Happy Go Lucky (Bernhardt, 1943) in which Betty Hutton energetically sings the song “Murder He Says” which contains the line, “murder he says in that impossible tone will bring on nobody’s murder but his own” (Figure 8.2). The suggestion here is that the narrative demands (and thus we expect) that Judah be brought to justice.

Figure 8.2 Betty Hutton sings “Murder, He Says” more cheerfully than Judah Rosenthal reacts to the murder he plots and purchases in Crimes and Misdemeanors.

(Producers: Robert Greenhut, Charles H. Joffe, Thomas A. Reilly, Helen Robin, Jack Rollins)

The final scenes from the movie screen of the Bleeker Street theatre occur right after Cliff learns that Halley will be leaving for London for work. Cliff and Jenny watch The Last Gangster (Ludwig, 1937), in which Edward G. Robinson’s Joe Krozac serves time in the notorious Alcatraz prison. The first image is of the all-imposing “Rock” in San Francisco harbor, but then we cut to a much later section of the film, a typical montage sequence signaling time passing through the superimposition of clock hands and the word “months” rolling over images of Robinson sweltering away at his demeaning prison job in the laundry. The connection here is that Cliff, too, suffers as he waits for time to pass. But instead of just allowing us to make the connection contextually, Allen conflates the two experiences by using a title superimposition of “Four Months Later” to introduce the next scene. Production notes indicate that Allen is very aware of this device: “Note that there will be no textless background for this title since Mr. Allen wants all audiences to see the title move onto the screen in the same manner as in the black-and-white clip . . .” (Gelula 1989: 176). In other words, Allen appears intent upon having us make the connection between the diegesis of Crimes and the worlds of the Hollywood clips. This interrogation through reflexive juxtaposition, if you will, of the various levels of cinematic experience is echoed in how Cliff, the filmmaker whose purported documentary is enfolded within the diegesis of Crimes, uses the same type of techniques (née shenanigans) in his send-up of Lester, thus further thickening the already rich, intertextual stew.

Another moment of watching an audience watch occurs not in a theatre but in Cliff’s editing suite. Cliff and Halley watch a scene from the musical Singing in the Rain (Donen and Kelly, 1952) on the flatbed editor. The idea that all film musicals are reflexive in and of themselves enjoys a rich history in scholarly discourse. The choice of this particular film, which is self-reflexive in that it’s a film about filmmaking, is doubly revealing. But this moment is distinct from the others, for we’re held at bay, denied the pleasure of watching the actual film itself. The camera, positioned behind the flatbed, slowly tracks right and then holds. We watch Cliff and Halley watch; never once do we see the scene that they see. If you know the film (and again there are certain demands here for willing and active participation) you can see it play across the movie screen of your memory. “All I do is dream of you,” the characters sing. We, to a certain extent, dream this film as we voyeuristically peer over the edge of the editing machine, reminding us that dreams themselves, and the act of dreaming, are a rich metaphor for the cinematic experience (Linden 1970: 175).

This is a convenient transition for us to now explore the more obvious of the reflexive story lines. Cliff Stern is a cash-strapped filmmaker who makes documentaries with limited appeal. He is stuck in a loveless marriage to Wendy (Joanna Gleason), a college professor who no longer has any appreciation for Cliff’s artistic endeavors. Cliff is lost in the impossibly long shadow cast by Wendy’s brother, Lester (Alan Alda), a wildly successful television producer with a “closet full of Emmys.” Cliff reluctantly accepts the opportunity to become Lester’s biographer, an arrangement that Lester offers out of familial responsibility to his sister, and which Cliff pursues to raise money to finish his current project, a documentary on the existentialist professor, Louis Levy. It is while in production of the Lester film that Cliff meets and falls for assistant producer Mia Farrow’s Halley Reed.

This obviously self-reflexive setup invites an investigation into the nature of the documentary in the age of commercialism. Surrounded by the apparatus of filmmaking, this plotline pushes forward with its consideration of the raw stuff of documentary, the gathering of actualities and the ethical responsibilities of storytellers. Cliff’s film about Lester is being funded by public television as a part of its ongoing “Creative Minds” series. Although cloaked in this nonprofit veneer, it is understood that these PBS documentaries are ultimately commercial enterprises with sizeable audiences expecting a diet of popular figures. In contrast, the Levy project is an artistic endeavor, a labor of love of personal expression, presenting a man who offers challenging ideas on morality and religion.

At first, we assume our sympathies should lie with the little man, Cliff Stern. His efforts appeal to the more noble aspects of documentary filmmaking, laying bare realities on shoestring budgets and confronting weighty, thought-provoking issues. We become acquainted with the Levy film in Cliff’s editing suite. Surrounded by trim bins, split reels, and shelves burgeoning with motion picture footage on cores, the Levy interviews grind through a six-plate, flatbed editor, the image a washed out workprint marred by grease pencils and scratches.5 It is here that serious documentary work is pursued, as we listen to Levy, shot in close-up, probe esoteric and cerebral concepts.

In contrast, we witness Cliff shooting his Lester film out in the streets of Manhattan and in Lester’s offices. Lester is presented as arrogant and full of bluster (among other things). His is a powerful presence, and we are manipulated into interpreting his pronouncements as nothing more than narcissistic nonsense. “If it bends it’s funny . . . if it breaks it’s not funny” is Lester’s oft-repeated line, which Cliff and, by extension we, meet with an eye roll and a head shake.

Allen, however, doesn’t allow us to swallow any of this framing easily. There is ambiguity – Lester actually shares many traits with Woody Allen, the real man behind the camera. For instance, he prefers shooting in New York City, takes on edgy issues, and, in spite of the fact that he never finished college, ivy league universities offer courses on the existential motifs in his comedies. All of this could have very easily been torn from the pages of Allen’s own biography. Then there is the question of who Lester really is. We hear comments from other characters of how generous Lester has been his whole life, supporting a number of charities and even paying for his niece’s wedding. And when Halley Reed, portrayed by Allen’s real-life paramour, for whom we have a great deal of respect if not affection, returns from London engaged to the egomaniacal Lester, what are we to think? “Give me a little credit, will you?” Halley asks Cliff, although she might as well be asking us, in the audience.6

We are forced, then, to consider the rather subjective idea of “story” – who controls it and where the “truth” lies. Although Cliff is the putative director, there is never any question that Lester assumes he’s in control, as he instructs Cliff as to what should and should not be filmed, or where they’ll pick up the line of questioning after a break from shooting. When we watch the rough-cut hatchet job in the screening room and realize that Cliff has mixed in both archival newsreel footage and outtakes from fictive film to compare Lester to Mussolini and Francis the Talking Mule, we’re not surprised at the outcome. Although Lester’s firing of Cliff might have more to do with ego than anything else, we cannot dispute Cliff’s violation of what Hampe would call a “sacred” principle of the documentary genre of never intentionally fooling an audience (Hampe 1997: 37).

Cliff’s blatant subjectivity finds its corollary in his Levy film. When the professor commits suicide Cliff is completely blindsided. Despondent (more over the loss of his film than anything else), Cliff seeks solace in his editing suite. As an interview unspools through the flatbed, we realize that the potential for Levy to take his own life had been there all along, captured in celluloid and on the magnetic recording tape. “But the universe is a pretty cold place. It’s we who invest it with our feelings. And under certain conditions we feel the thing isn’t worth it anymore,” Levy opines, and then the film, literally as well as metaphorically, runs out. A skillful documentary filmmaker might see a great (albeit ghoulish) opportunity in this tragic turn of events. This is not the film that Cliff wants to make, however, and, in choosing to ignore Levy’s surrender to the bleakness of life, he draws attention to how similar documentaries and fictive films really are in their construction of stories (Vighi 2002: 492). Ironically, Levy, much like Lester, also takes over Cliff’s film by indirectly asserting control over the story through the taking of his own life, forcing Cliff to abandon the project.

As much as the Cliff Stern plot is “filmmaker as character,” the Judah storyline can be seen as “character as filmmaker,” although it’s far less transparently reflexive. This is understandable. The morality play of “(m)urder and infidelity, the existence of God and human responsibility” (Vipond 1991: 99) justifiably overshadows any other suggested interpretation. As John Pappas writes, the seminal question of “[i]f we knew we could get away with murder would we be able to rationalize it?” (2004: 204) can easily absorb most of a viewer’s attention. However, if we’re willing to do the work, we can recognize that the raw reflexive material is nonetheless present, with Judah’s desperate struggle with his conscience serving as a search for an alternate resolution to the classical Hollywood model.

In Judah’s opening speech, he not only speculates on the eyes of God, but also introduces the concept of his always having been a religious skeptic. If we interpret this skepticism toward religion as a substitute for his desire to subvert the expected narrative, all the pieces can fall into place. The Old World religious point of view embodied by Sam Waterston’s rabbi, Ben, represents the inherent structure of cause and effect, an Aristotelian logic that is deeply embedded in the Hollywood model. Reflexive filmmakers are, if anything, always in search of ways to subvert this intended order. As such, Judah confronts these conventions through Ben, within the milieu of the eye examinations, and their relationship becomes symptomatic of this struggle over cinematic narrative design. Associating eyes with cameras may be clichéd at this moment in time (Friday 2001: 359), but it’s had a rich and fruitful relationship since the days of the camera obscura (Ihde 2000: 21). Even the ophthalmic apparatus, with projectors casting beams of light on screens in darkened rooms, extends this metaphor. The first time we observe Judah as he examines Ben’s eyes, Judah is seeking to assert control as he directs Ben to follow a projected spot of light in the dark. Ben confirms that he sees it, but Judah sighs, “Oh, God,” and asks for a break; the tension here can be construed to be not merely about Judah and his conscience, but about Judah’s confrontation with the inevitabilities of the conventional narrative structure. After Judah comes clean about his affair, Ben holds to the rational story arc of confession and forgiveness. But this, not unlike Cliff’s struggles with both Lester and Levy, is not the story resolution that Judah desires. To underscore this point, this same conversation is revisited as Judah, again in the dark but this time in his home, lit by the light of the fire and flashes of dramatic lightning, comes to the conclusion that he must order the murder of his mistress.

The next time Judah examines Ben in the dark it is after the murder. Ben inquires about Judah’s “personal difficulties,” and Judah responds that the woman had “listened to reason.” Ben then says, “That’s wonderful. So you got a break. Sometimes to have a little good luck is the most brilliant plan.” Maybe so, but this “deus ex machina” strategy is without dramatic logic, and satisfies neither the conventional narrative nor audience expectations very well. Ben’s impending loss of sight then can be construed as the emerging impotence of the classical story structure, exposing it as the mere “organizational principle within the cumulative randomness of events” (Bottiroli 2002: 14).

This malleability of story lives at the heart of Crimes. In the Passover Seder sequence in which Judah not only observes but, in a signature Allen strategy,7 interacts with characters within a flashback, Aunt May (Anna Berger) and Sol (David S. Howard) debate the relevance of the ritual retelling of the exodus story. Aunt May (a person to whom Judah is later favorably compared) brings up the contemporary issue of Hitler and the Holocaust, and poignantly asserts that, had the war turned out in the Nazis’ favor, history would tell a decidedly different story. “History is told by the winners,” May pronounces, reminding us that the invention of narrative is as much a construction of artists as it is an “objective record of true facts” (Frus 2008: 54). To this, Sol takes great umbrage, insisting that, “whether it’s the Old Testament or Shakespeare, murder will out.” That he associates biblical narrative with a dramatic conceit is key, and when he concludes that given the choice, he would always choose God over the truth, he concedes, within this interpretative landscape, that he chooses a preordained story structure over the uncertainty of nontraditional, if not unstructured, events.

This discourse speaks directly to Professor Levy’s observations of the paradoxes inherent in certain stories. We watch and listen as he lectures to us from the flatbed editor’s screen, commenting on how the early Israelites could not imagine a truly loving image of God, as he demands Abraham to sacrifice his only son. Later, he underlines the contradictions of love, how we simultaneously desire to both return to and undo the past. If anything, art represents our human attempts to get things that don’t go well in life to work out right, a point Alvy Singer makes towards the end of Annie Hall when we witness a rehearsal of his play in which the breakup scene, that we have just witnessed, is reworked to have the Annie character decide to return to New York with the Alvy character. “[W]hatta you want? It was my first play,” Alvy explains directly to us, breaking the fourth wall. “You know . . . you’re always tryin’ t’get things to come out perfect in art because . . . it’s real difficult in life” (Allen 1982: 102). Story, here, is shown to be pliable enough to even recast the actual role of “the winner.”

Again, in sequences that are both intratextual (Sol and Levy) as well as intertextual (Annie and Crimes), we are asked to reflect on the narrative and how it makes meaning. Both moments are reflexive, whether through the subversion of conventions (Judah interacting with his flashbacks) or in our witnessing Levy, mediated through the apparatus of filmmaking (the flatbed editor).

I arrived at this reading through the process of heuristic inquiry, in which, as Moustakas suggests, we become aware of the interplay of our own conscious and unconscious minds, and actively seek to harmonize the two (Moustakas 1990: 28–29). To illustrate this point, I must indulge in some reflexivity myself and break from the traditional conventions of scholarly discourse to reveal a little of my own processes in the creation of this chapter. The moment I wish to discuss occurred late at night. I had just concluded reviewing the latest draft, in particular sifting through the possibilities offered up by Allen’s choice of the Hitchcock film Mr. and Mrs. Smith and how it colored my subsequent interpretations. As I slipped into bed and began to drift into the lovely twilight state that limns the borders of the dream world, I was suddenly confronted by an image of Mount Rushmore. Running around on the iconic faces chiseled into the rock were three people engaged in a desperate cat and mouse game. “In heuristic investigations,” Moustakas writes, “[we] may be entranced by visions, images and dreams that connect (us) to (our) quest” (1990: 11). I quickly recognized it was a scene from Hitchcock’s splendid North by Northwest (1959) with Roger Thornhill (Cary Grant) and Eve Kendall (Eva Marie Saint) being pursued by the cloying henchman Leonard, played by none other than a callow Martin Landau, appearing in only his second feature film.

After a moment’s confusion, I leapt out of bed and frantically fumbled for a pen and paper in the dark. The word “heuristic” comes from the Greek “heuretikos” which means “I find” and is related to the more familiar “eureka” (Douglass and Moustakas 1985: 40), a word I wanted to shout but, mercifully out of deference to my sleeping spouse, didn’t. North by Northwest, if anything, is a film that Stanley Cavell invites us to (re)interpret as a boldly reflexive film, not only in regards to its source material of Hamlet but in its investigation of the relationship between life and art (Cavell 1986: 251–254). Now, I am not asserting that this had any influence over Allen’s casting choice, or that it even occurred to him; intentionality on the filmmaker’s part is not essential when reading for meaning in a film (Frus 2008: 59). What I am drawing attention to is the interplay between our expectations as scholars and critics and motifs that occur within and across films. It is a complex matrix, but once Allen introduces someone such as Hitchcock into the mix, many Hitchcock-inflected moments suddenly become evident in the film; once you ring this particular bell, it’s difficult to un-ring it.

Take, for example, when Judah drives his car to revisit his boyhood home. There is a shot/reverse shot sequence that is very reminiscent of Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) in Psycho (1960). We see Judah as he drives; we hear, in voiceover, his thoughts; and we see, from his subjective point of view, where he’s driving (in this case, through a dark tunnel). Then there is the moment that Judah returns to the scene of the crime to retrieve some incriminating personal effects. He stands over Dolores’ body and stares down in horror. The camera moves in a very atypical way for Allen – a long, slow tilt and pan, down the length of Judah’s body, to Del’s face and her lifeless eyes, then back again. This move is very reminiscent of the aftermath of the murderous shower scene in Psycho. It is atypical of Allen, because he is most noted for his love of master shots and mise-en-scène (Lax 2007: 199). It is rare that the camera makes itself known in such a manner.8 Hitchcock, on the other hand, is well known for quite the opposite: his restless, moving camera that always reminds us of the man in the director’s chair.

Let us now revisit the last eye examination when Judah shines the light of his projector into Ben’s eye. This inspires a flashback to when Del asks Judah, early on in their relationship, if he agrees that “the eyes are the windows of the soul.” Judah responds, “Well, I believe they’re windows, but I’m not sure it’s a soul that I see.” Although the implication is supposed to be sexual, the introduction of the concept of “windows” allows us to come back into the intertextual dialogue with Hitchcock, who uses windows so prevalently in such films such a Shadow of a Doubt (1943), Psycho, and, most prominently, Rear Window, with the suggestion that frames within frames offer opportunity to reflect on the very nature of the cinematic experience itself. If all art is in some measure about itself, then this kind of reflexivity draws us even closer to the dialogue (Affron 1980: 42).

But probably the primary “Hitchcockian” moment is a manipulation of our perception of character and thus our response to that character’s murder. Dolores Paley is not a particularly sympathetic woman – she is played as high-strung, unreasonable, and neurotic. Judah calls her a hysteric, and we can hardly disagree with him. Thus, when she is murdered, offscreen, we feel perhaps a little ambivalent. Hitchcock does this kind of manipulation in Strangers on a Train (1951). Miriam (Kasey Rogers), the wife of Guy Haines (Farley Granger), is unsympathetically played. She is shrill, manipulative, and an unreasonable impediment to Guy’s happiness, and so we don’t feel terrible when she’s murdered, despite Guy’s revulsion when Bruno (Robert Walker) reveals his awful deed. Judah similarly is repulsed by the suggestion of murder made by his brother Jack (Jerry Orbach), and so to a certain extent he distances himself from the foul plan.

If anything, these allusions to Hitchcock add to the cumulative effect of the reflexive dialogue interwoven into Crimes. Motifs that refer to watching and vision, beyond those already addressed here, weave their way into the very fabric of both plots, either directly or indirectly, in large ways or smaller, quieter ones, almost in reflection of the film’s title. For example, when Judah and Del are on an apparently deserted beach, Judah becomes uncomfortable for fear that someone might be watching; Aunt May demands of Sol to “open your eyes” to how people can escape punishment; in an argument with Wendy, Cliff asserts that Halley’s staring at Lester is a result of her not being able to “believe her eyes”; Lester invokes Oedipus; Halley assures Cliff, “I’ll be seeing you” when she breaks away after their first kiss; and even the music contributes, with “Jeepers Creepers” (where did ya get those peepers) and, for the closing montage, “I’ll Be Seeing You.” Thus in both plots, in flashbacks and in the films within the film, subtle, reflexive motifs echo throughout in an almost call and response dynamic.

All of this points us towards the end of the film. In the penultimate scene, Cliff and Judah, our two main protagonists, finally meet. We in the audience, of course, are well aware of their respective backstories, which have, on the surface, run in parallel, with supporting characters crossing lines, dipping in and out of both of their lives. Now they get a chance to “compare notes,” if you will. They’ve both sought out some quiet amidst the joyful tumult of the wedding of Ben’s daughter, and Judah stumbles upon Cliff, alone in a room. Judah observes the obvious (“Off by yourself, eh?”), but then says, “You’re like me.” Although this refers to their choice of finding solitude, or even, perhaps, that they’re both “well lubricated,” it can also be read as the comparison of their twin struggles over the control of the narratives that we’ve witnessed throughout the film. To reinforce this reflexive track, the topic of movies and murder comes into the conversation:

| Judah: | You look deep in thought. |

| Cliff: | Yeah, I was plotting the perfect murder. |

| Judah: | Yeah? Movie plot? |

This takes Cliff by surprise, for we are to assume he is thinking (albeit not very seriously) of a possible real-life murder of his rival in love, Lester. Ironically, Judah, who has apparently committed the perfect murder, refocuses us on the world of fiction. “I have a great murder story,” he begins, but realizing that he might be going too far, he attempts to break it off. Cliff, however, invites him to continue, and after a cut to another scene, we return to Judah, now in a medium close-up, staring off into the distance, having divulged, we assume, the spine of the real-life murder of Dolores. He tells Cliff of the “character’s” inner struggles with guilt, issues that we have seen plague Judah after the actual murder. But then “one morning, he awakens. The sun is shining and his family is around him and mysteriously the . . . crisis is lifted. . . . he finds he’s not punished. In fact, he prospers.” Essentially, Judah pitches the narrative that has been revealed through the diegesis of Crimes as a fictive piece with an unexpected ending (which, in essence, it is).

Cliff counters that in order for the film to achieve “tragic proportions” the character must assume responsibility and turn himself in. Judah looks at him in surprise. “But that’s fiction. That’s movies,” he responds. “You see too many movies. I’m talking about reality. If you want a happy ending, go see a Hollywood movie.” In other words, Ben’s Old World construct of cause–effect, of crime and punishment, the hallmark of classic Hollywood, has no standing in Judah’s story.

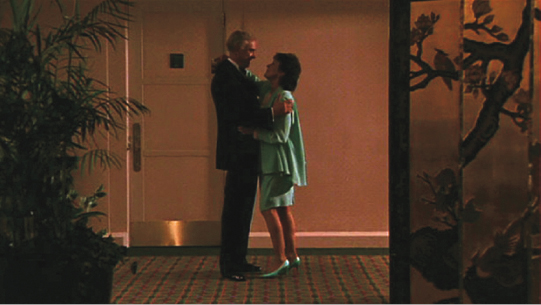

To punctuate this point, Judah’s wife Miriam interrupts, suggesting that it’s time to leave. After bidding Cliff farewell, Judah joins Miriam, where they’re both framed in the proscenium arch of the doorway, perfectly lit as if in their own movie. Faint applause is heard as they embrace, murmur love devotions, and plan for a presumably (and scathingly paradoxical) happily-ever-after future (Figure 8.3).

Figure 8.3 Judah and Miriam Rosenthal are happily ever aftered in the close of Crimes and Misdemeanors.

(Producers: Robert Greenhut, Charles H. Joffe, Thomas A. Reilly, Helen Robin, Jack Rollins)

The camera then swings back to Cliff. When he first was resistant to take on the task of shooting Lester’s documentary, Lester recorded an idea into his ever-present, pocket tape recorder. “Idea for farce: . . . a poor loser agrees to do the story of a great man’s life, and in the process comes to learn deep values.” This would be the expected character arc of the traditional narrative. Cliff, through losing Halley to his nemesis, on the verge of divorce and with no prospects of finishing any of his work, should learn from his mistakes and experiences and, if not change course, then at least give us some sign that he is now a bit wiser for all the tumult and effort. But the only sense that we have is that he is condemned to continue his life of lonely, quiet desperation and we’re not convinced he’s actually learned anything at all.

The final section of the film is anchored with Ben, the now blind rabbi, dancing the traditional father/daughter wedding dance, to the tune, “I’ll Be Seeing You.” As cruelly ironic as this may seem, we’re then presented with a montage of images from a variety of moments within the film we’ve just watched. They all represent crucial plot points in both the Cliff and Judah storylines, but they appear in no particular narrative order, shuffled like a deck of cards. The context is supplied by Professor Levy’s voiceover narration, as he ponders how we are defined by the choices we make. We jump through time and space, seeing Judah and Del argue, then the aftermath of Judah making the phone call ordering her murder, back to Judah and Jack in the pool house, and then to the flashback of the Seder dinner. Intercut with these scenes are excerpts from the Cliff plot, when he kisses Halley, then the newsreel footage of Mussolini on the balcony, to Lester pestering Halley as she attempts to talk on her cell phone, and then Cliff and Jenny, on the sidewalk and eating pizza.

From the moral perspective, meaning can be derived from the skillful juxtaposition of Levy’s words with the passing images. “We are all faced throughout our lives with agonizing decisions. Some are on a grand scale,” supports the images of Del and Judah; “Most of these choices are on lesser points,” refers to Halley and Cliff’s furtive kiss in the editing room, and so on. However, what is also intriguing here is that in a relatively short montage sequence we get to experience the totality of the film in an order not necessarily linked in a linear, dramatic line.9 The cause/effect connection is subverted. “Human happiness does not seem to have been included in the design of creation,” Levy intones, as we watch an excerpt from the Seder dinner juxtaposed with Del, walking in the street on the night of her murder. Levy could just have been easily addressing the narrative design of Crimes, however, which offers no predictable narrative and no happy resolutions. Levy’s final words, that we keep trying with “the hope that future generations might understand more,” are ambivalent, at best, although I will admit that, at one point in my life, I determined them to be rather hopeful (Bachman 1996: 186). But within the present context, the film concludes with a shrug. The audience, in the guise of the wedding guests, applauds offscreen, drawing our attention once again to the fact that we’re experiencing an artistic construction whose meaning, in the end, future generations may be able to figure out. Maybe . . . or maybe not, for we can’t forget that these hopeful words come from a character who has killed himself.