14

The whole realm of Scotland, with the exception of Berwick, now lay in the hands of Robert Bruce, and no King of Scots before or since has had a greater knowledge from his own experience of the character and condition of his people from the feudal aristocracy, with whom he had been brought up at court and tournaments, to the humblest serf, in whose hovel he had found shelter when a fugitive from his foes.

Whatever had been the driving force of his career at its outset – a desire for personal aggrandizement or patriotism or a compound of them both – Scotland was now in his charge and he would labour for her welfare. For her prosperity he needed peace, for her dignity the recognition of her independence and her chosen king, for her spiritual comfort the removal of the papal interdict. Throughout the remainder of his reign his whole policy was governed by his determination to achieve these ends.

He had no wish to prolong the war. He saw his victory, above all, as an opportunity for reconciliation: with the Scottish nobles who had fought against him, with the English whom he had defeated. Soon after Bannockburn many Scottish barons and knights who had served under the two Edwards offered to him their allegiance and were received into his peace. In November 1314, a parliament convened at Cambus Kenneth adjudged that all Scottish landowners who had failed to do so by that date should be disinherited.1 But Bruce treated this as an enabling statute only and granted a year’s grace before enforcing dispossession. His sole proviso was that those who wished to regain their Scottish lands must do homage to him alone. They could no longer be feudatories in two countries and serve two kings. They must choose their nationality once and for all: a decisive break for the multinational feudal system that had hitherto prevailed. In the event, the great majority became his subjects and with few exceptions served him faithfully. He was less successful in his relations with England.

In the immediate aftermath of Bannockburn he had returned unasked to Edward II the Great Seal of England and the Royal Shield which had been captured in the battle, in the hope that this gesture of amity might elicit a statesmanlike response from the English King. But Edward II had been too humiliated by his defeat and shameful flight, and too conditioned by his father to abhor the Scots, to rise above a petulant childishness when dealing with that race. The opportunity to restore the amicable relations which had existed between his grandfather and Alexander III, and which could have prevented four hundred years of strife between the two nations, was ignored. He made no concession to Bruce’s overture, and soon after was embroiled with the four earls, Lancaster, Warwick, Surrey and Arundel, who had absented themselves from his invasion, and was virtually deprived of his executive powers.2

Bruce had no alternative but to try to obtain by force what was denied to civility. His troops, who were filled with that elation which comes to those who have fought in war and against all odds have foiled their enemy, were impatient for action. In August 1314, under Edward Bruce, James Douglas and John Soulis (great nephew of the guardian of that name), they were let loose to sweep through Northumberland, County Durham and into Yorkshire as far south as Richmond, exacting tribute and gathering spoil, and back by Cumberland burning Brough, Appleby and Kirkwold on their way.3 In December of the same year, Bruce himself carried out a second raid along the Tyne valley, occupying Haltwhistle, Hexham and Corbridge, resuming the lordship of Tynedale which had formerly belonged to Alexander III, receiving from the men of that area a down payment for a truce to midsummer 1315 and their feudal homage to him as their Lord.4

Early in 1315 yet a third raid was mounted under James Douglas and Thomas Randolph, Earl of Moray, driving deep into County Durham and sacking Hartlepool.5 The northern English, unsupported by their King, were completely demoralized and made no resistance. ‘A hundred English,’ wrote their chronicler Walsingham describing the state of their mind after Bannockburn, ‘would not hesitate to fly from two or three Scottish soldiers so grievously had their wonted courage deserted them.’6

But however useful were the droves of cattle and ransom monies to Bruce for the needs of his kingdom, he realized that these raids in no way shook the structure of England. The wealth of the country, its shipping, trade, industry, manpower and food production were all in the south and Midlands. The northern counties – pastoral, sparsely populated and remote from the centres of government – could temporarily be sacrificed without halting the pulse of the country, provided that the great fortresses of Carlisle, Berwick and Norham remained in English hands as bases for recovery. To bring his enemy to terms, the Scottish King needed to strike in a more sensitive area and it was this consideration that determined him to open a second front in Ireland.

* * *

Throughout the thirteenth century there had been a great surge forward in the prosperity and settled habitation of that country under the Anglo-Norman conquerors, but during the wars of Scottish independence Edward I had made it one of the main sources of supply for his army in Scotland.7 Irish troops were responsible for much of the western marches and Irish ships for the provisioning of the Galloway castles. By the end of his reign the forces and exchequer of Ireland had been so denuded by his demands that its Lord Lieutenant could no longer prevent the spread of lawlessness and disorder.8

Edward II made several half-hearted attempts to repair these deficiencies, but once again the requirements of his armies against Scotland caused him to claw back more than he had supplied and the situation grew worse.9 His defeat at Bannockburn by a mainly Celtic army roused the expectation of his subject Celts. The recovery of their independence no longer seemed a chimaera.

Taking advantage of this new mood, Bruce, early in 1315, sent envoys to Ireland carrying with them the following message:

The King sends greetings to all the kings of Ireland, to the prelates and clergy, and to the inhabitants of all Ireland, his friends.

Whereas we and you and our people and your people, free since ancient times, share the same national ancestry and are urged to come together more eagerly and joyfully in friendship by a common language and by common custom, we have sent over to you our beloved kinsmen, the bearers of this letter, to negotiate with you in our name about permanently strengthening and maintaining inviolate the special friendship between us and you, so that with God’s will your nation may be able to recover her ancient liberty. Whatever our envoys or one of them may conclude with you in this matter we shall ratify and uphold in future.10

A desired response came from the O’Neills, the royal line of Ulster, who sent emissaries to Robert Bruce asking for military aid against the English and offering the throne of Ireland to his brother Edward.11 The moment was propitious. Throughout his career Robert Bruce had maintained close links with the men of Ulster and was well aware of the disintegrating state of the country. From the strategic point of view a friendly Ireland, offering a base from which to threaten the west of England or to combine with an insurrection of the Welsh, could provide a powerful bargaining counter against the English. From the personal point of view it would be a welcome relief if the savage energy of his brother could be afforded employment at a distance, for his jealous ambition was already threatening the tranquillity of the state. According to one chronicler he had declared that Scotland was too small to contain both Bruces, and according to another that he could not live in peace with his brother unless he was granted sole rule of half the kingdom.12

Bruce had gone some way to soothe his discontent. In April 1315 a parliament was held at Ayr to consider the succession to the throne. Separated from his wife for eight years, Bruce had no legitimate son. His heir presumptive was his daughter Marjorie, about twenty years old, recently returned from England and soon after betrothed and married to Walter Stewart. On the grounds that the continuing peril from England demanded an experienced man at the head of affairs, Marjorie, on her father’s advice, agreed to waive her rights as heir in favour of her uncle Edward, described in the entail as a man ‘strenuous and skilled in the arts of war’. If Robert Bruce should die without a legitimate male heir, the crown should pass first to Edward, then to his heirs male, then, failing these, to Marjorie and her heirs. If the succession fell to a minor, Thomas Randolph, Earl of Moray, was to act as regent.13

At the same parliament the appeal from Ireland was considered and a decision taken to send there an expeditionary force under the command of Edward Bruce. No man was readier for action. He was one who, like the hero of the Chanson de Geste, would have declared, ‘If I had one foot in Paradise I would withdraw it to go and fight.’ Now his craving for the clash of steel and the glitter of a crown could be satisfied in full, while, at the same time, he would be carrying out the strategic objective of his royal brother: to harass England in her most vulnerable quarter. So important was this to the Scottish King that he put at Edward’s disposal 6000 veteran soldiers and, knowing the headstrong and reckless character of his brother, designated to accompany him Thomas Randolph, Earl of Moray, on whose combination of judgement and courage he could rely.

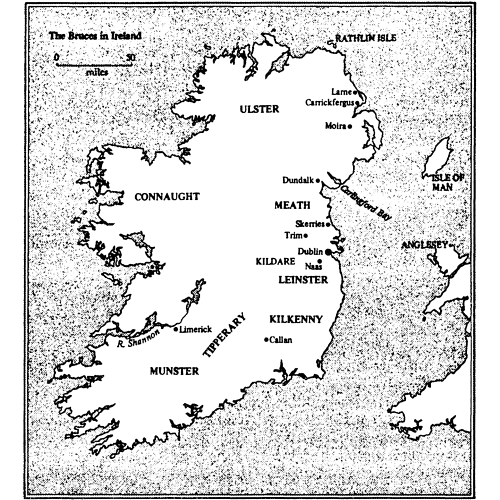

On 26 May 1315 the Scots landed at Larne near Carrickfergus in Ulster.14

Within a month of their landing, they defeated the Anglo-Irish barons of Ulster at Moiry Pass in Armagh and, after concluding a truce with the defenders of Carrickfergus castle, drove south to Dundalk and on 29 June 1315 put the inhabitants to the sword.15 Taking advantage of the dissensions between the Anglo-Irish leaders, they defeated piecemeal the Earl of Ulster at Connor on 10 September 1315 Roger Mortimer at Kenlis at the end of December, and on 1 February 1316 routed Edmund Butler, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, at the battle of Skerries in Kildare. The road to Dublin was open. But the devious behaviour of the native Irish chieftains who, on two occasions by treachery, involved the Scots in situations from which they extricated themselves with difficulty,16 decided Edward Bruce to retrace his steps to Carrickfergus to capture the castle and make certain of the base from which he could maintain his supply line to Scotland.

Once again his success in open warfare was almost annulled by deceit. While investing the castle he agreed with the governor that a truce should be observed over the holy week of Easter so that men might spend their time in penance and prayer. But on the night of Easter Eve fifteen ships from Dublin, loaded with armed men under the command of Sir Thomas Mandeville, slipped into the bay and entered the castle by a seaward gate. The Scots, with no thought of treason, were scattered about the countryside or in lodgings in the town below, leaving only Neil Fleming and sixty men to watch the castle gate which fronted on the town.

At first light the garrison of the castle and their newly arrived reinforcements let down the drawbridge and burst upon the unsuspecting Scots. When Neil Fleming saw them he sent a messenger in haste to warn Edward Bruce, and then with his little band pressed forward to hold the enemy at bay and fought them hand to hand until all his company were killed. The respite occasioned by this defence gave Edward Bruce and the twelve knights who were in his quarters enough time to arm and make for the battle with their followers. As soon as they joined the mêlée they drove towards Sir Thomas Mandeville and, one of them felling him to the ground with his axe, Edward turned him over and dispatched him with his dagger. Meanwhile the scattered Scots, as fast as they could arm, hurried to the fray, some to the castle gate and some to the ships, until their opponents, disheartened by the death of their leader, fled back within the castle walls.

When the fighting was over, Edward Bruce looked among the fallen for Neil Fleming. He found him scarce alive with his followers in a heap on either side. He stayed by him until he died and at his death he wept. In all his life this was only the second time he had been known to weep.17

Three weeks later, at Dundalk on 2 May 1316, Edward Bruce was crowned High King of All Ireland.

* * *

A crucial factor in the success which had attended the Scottish invasion of Ireland was control of the narrow seas between the two countries.18 In the summer of 1314, while Bruce was engaged in the defence of his country against England, John of Lorne, who after his defeat at the Pass of Brander had been appointed by Edward II Admiral of the Western Seas, landed on the Isle of Man and ousted the Scottish garrison. From there he began to canvass the petty chieftains of the Outer Isles and the seagoing men of Argyll to form a maritime opposition to the Scottish King.

Bruce was not slow to realize the danger to his strategy. As soon as the ships which had transported Edward Bruce and his army to Ireland had returned, he made an expedition to the Western Isles accompanied by his son-in-law Walter Stewart. Sailing up Loch Fyne, he bypassed the long beat around the Mull of Kintyre by laying pine trees side by side across the narrow neck of land which separates the lochs of East and West Tarbet and taking his ships over them partly by manpower and partly by hoisting their sails to catch the strong wind that blew from the east. So unexpectedly did he break into the open sea beyond that the men of the isles recalled the ancient prophecy that whoever should sail across the isthmus should have dominion over them. One by one they came to do him homage. John of Lorne was left without supporters and retired to England ‘impotent in body and his lands in Scotland totally destroyed’, there to receive a pension from Edward II until his death in 1318.19

A swarm of island privateers, under the protection of the Scottish King, now threatened the coastal towns of England and the merchantmen who plied between them and Ireland. Chief of these marauders was Thomas Dun, who on 12 September 1315 with four Flemish sea-captains sailed into Holyhead, captured an English ship and overawed the island of Anglesey.20 A rumour spread that Edward Bruce was about to cross from Ireland and restore the ancient liberties of Wales, and the Welsh rose in revolt under Llewellyn Bren. Edward II had to countermand the Welsh levies who had been summoned to join the army he was preparing against Scotland, and when the French King requested the aid of the English navy against the Flemings, he had to reply that all its ships were required for the defence of Ireland.21

So far Bruce’s strategy was proving successful. The English were too occupied in dealing with their Celtic subjects to reinforce their northern strongpoints, and gave an opportunity to Bruce to attack them. On 22 July 1315, after ravaging the surrounding districts and driving in the cattle to feed his army, he laid siege to Carlisle. For the first time the Scots had been able to acquire and bring with them siege artillery. But their single stone-lobbing machine was no match for the eight employed by the defenders. The high tower they proposed to wheel up to the walls sank in the swampy ground before it reached its objective. The shelter they built to protect their sappers while they undermined the fortifications suffered the same fate. Nor under the hail of arrows from the battlements could they fill the moat with sufficient bundles of brushwood to form a causeway.

In a last attempt to win success Bruce reverted to the element of surprise. On 30 July he assaulted the eastern side of the city with the greater part of his army, while James Douglas with a picked force of nimble men set up exceptionally long ladders against the western wall where the height and difficulty of access was regarded as adequate defence. But the garrison contained a large contingent of archers, and when the first assailants were observed in that quarter they directed their fire and picked off all who appeared above the parapet. The Scots had been foiled.

On 1 August Bruce cut his losses and returned to Scotland, leaving his siege equipment behind.22 This was the first English success for a number of years, and the Governor of Carlisle, Andrew Harclay, received one thousand marks from Edward II as a mark of his appreciation.

Six months later Bruce and Douglas made a surprise attack on Berwick on a black night in January 1316, but the moon came out as they approached the uncompleted wall by the harbour and they were repulsed.23

Nevertheless, the inhabitants were in a precarious situation. The Scottish fleet was cutting off supplies. From the autumn of 1315 a stream of letters was sent to the English King complaining that men were dying of starvation and that even the horses were being eaten. 24 In February 1316 a party of the defenders under the King’s Sergeant at Arms, Sir Raymond de Calhoun, a Gascon knight, against the orders of the governor, went foraging throughout Teviotdale, saying that it was ‘better to die fighting than to starve’.25 News was brought to Douglas in Selkirk forest that there was only a handful of skirmishers rustling cattle, and he set out after them with the few men he had about him. When he came up with them at Scaithmoor he found that there were a vastly greater number of knights and their followers than his own. But it was not in his nature to turn back. It was, he said afterwards, the hardest fight he ever fought. But he won it by concentrating his attack on the enemy commander. His little bunch hewed their way to close quarters with Sir Raymond, and when Douglas dispatched him hand-to-hand the rest lost heart and fled.26

The fugitives from this encounter excused their flight from so small a force by ascribing it to the demonic power of the Black Douglas. A Northumberland baron, Sir Robert Neville, whose character was encapsulated in his sobriquet ‘the Peacock of the North’, provoked by these reports of the invincible valour of the Scottish knight, challenged him, at his peril, to appear before the walls of Berwick. Douglas immediately marched to that neighbourhood, shattered Sir Robert’s forces, slew him with his own hand and took his three brothers prisoner.27 The considerable ransom he received in return for their freedom went to defray the expense of the hunting lodge he was having built at Lintalee in the forest of Jedburgh.28

While these activities were taking place, Bruce had returned to his family. His daughter Marjorie was expecting a child in the spring. This was a matter of some moment as his own wife Queen Elizabeth had not conceived since her return from England. On 2 March 1316, when near her time, Princess Marjorie was thrown from her horse and killed. The surgeons who were sent for, conscious of the succession, at once cut open her abdomen and delivered a son from her dead body. Crippled throughout his life from the injury of his birth, the boy, fifty-four years later, became King of Scots as Robert II, the first of the royal line of Stewarts.

When the obsequies of his daughter were over, the King in person, hearing that a muster of an English army was in train, led a raid in force deep into Yorkshire. By midsummer he had reached Richmond, into whose castle the nobles and gentlemen of the surrounding country had ridden for refuge. They offered a very large sum to be left unharmed, which he accepted. He then turned west, leaving a trail of pillage for sixty miles, into the Furness district of Lancashire. There he laid his hands on the accumulated stock of iron ore and had it brought by captives to Scotland where it was in short supply.29

Three months after his return, Randolph came to him from Ulster with the news that Carrickfergus castle had fallen and that Edward Bruce was only waiting for the arrival of his royal brother, with further troops, to complete the conquest of Ireland.30

* * *

To the end of his life Bruce remained sensitive to the danger from Ireland if it was in unfriendly hands. For him the short sea passage between Ulster and his vulnerable western seaboard was a boundary to be protected no less than the borders themselves. If now there was an opportunity to break the power of the English in Ireland he was prepared to take a calculated risk. A secure base had been established. He had confidence in Randolph’s judgement. An attack on Scotland from the south while Edward II and the Earl of Lancaster were at loggerheads could be discounted. Leaving James Douglas and Walter Stewart as regents of his kingdom, he crossed to Carrickfergus in the autumn of 1316 at the head of a considerable army.31

There was an ancient custom that whoever became High King of Ireland should make a royal progress through all the provinces of Ulster, Meath, Leinster, Munster and Connaught.32 To conform to this usage and thereby stamp the legitimacy of Edward Bruce’s coronation on the minds of the native Irish chieftains and win their adherence, it was decided that the two brothers should ‘make their way with their whole host through Ireland and from one end to the other’.33 In February 1317 they left their base at Carrickfergus moving south in two divisions, Edward Bruce commanding the van and Robert the rear.

Almost at the outset the impetuosity of Edward nearly brought disaster. The Anglo-Irish barons under the Red Earl of Ulster had had hidden their men in an ambush along the route. Edward, who by then had pushed recklessly ahead without maintaining contact with his brother, they let pass by and prepared to take the rearguard by surprise. But two archers, stepping from the woods to fire at Robert’s men, alerted the King to the possibility of a trap and he ordered his troops to halt and take up fighting formations. His nephew Colin Campbell, with youthful enthusiasm, started to charge toward the archers. He was quickly overtaken by his uncle, who gave him a resounding buffet that made him reel in his saddle and a sharp rebuke for disobeying orders. It was well that he had been checked, for within minutes hundreds of the enemy came out of the woods on either side greatly outnumbering the Scots.

It was the bitterest encounter in all the Irish war, and if Bruce’s military instinct had not caused him to marshal his men in time, they must have been overwhelmed. Not for nothing had he been named one of the three greatest knights in Christendom. This time he was in the thick of the fight. With Randolph, scarcely less renowned, and other tried companions beside him and a body of veteran soldiers, he gradually gained the ascendancy. Although they were eight to one against the Scots, it was the Anglo-Irish who gave the order to retreat and make in haste for Dublin. 34

Their arrival there roused the inhabitants to a frenzy of activity. For months they had been demanding the authorities to put the defences of the city in order. Now, with the knowledge that the Scots were only eight miles away, they took matters into their own hands. They clapped the defeated earl in gaol as a traitor, set fire to the suburbs of wooden houses, burnt the bridges across the Liffey and tore down the belfry of St Mary’s Church to provide stones to repair the breaches in the walls. Their spirited defence had its effect. As Bruce watched the flames rising around the city from his camp at Castleknock, he doubted, after the losses he had suffered, that he had the men or the time to succeed in a siege against resolute opponents.35

He had with him one of the Irish chieftains, Brian Ban O’Brien, whose clan was powerful in the southwest. O’Brien promised that if the King rode into Munster there would be a general uprising in his favour. So Bruce decided to bypass Dublin, march south by Naas in Kildare and Callen in Kilkenny, ravaging the lands of the Anglo-Irish on the way, and then turn west towards Limerick. But when the Scots reached the Shannon hoping ‘to effect a junction with the whole Irish army at Saingrel’, they were grievously disappointed. As happened more than once throughout the campaign, clan feuds overrode the Irish desire to be free of the English yoke. Brian O’Brien’s clan rival was Murrough O’Brien. Automatically, he supported the opposite side and when Bruce reached the river, Murrough’s ‘Army of Thomond’ was mustered on the farther bank ‘with intent to strike’.36

Bruce was already anxious about his expedition. The great European famine of 1315–17* had spread to Ireland and was at its worst in the southwest. Even without clan quarrels the rallying of Irish chieftains for concerted action was virtually impossible while famine gripped their domains. News, too, had reached him that Sir Roger Mortimer, newly created Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, was consolidating the forces raised by his predecessor, Edmund Butler, in Cork and Waterford to cut off his return to his Ulster base.37 He gave the order for retreat. The troops were ready to set off when he heard a woman’s shriek. Asking the reason for this, he was told that it was the cry of a laundress who was in the pangs of childbirth and must be left behind.

At this he halted his army, saying that no woman in such a state should be deserted, and he gave orders that a tent should be pitched and that other women should stay beside her until her child was born, and that arrangements should be made for mother and child to be carried with the troops. Only when this was done did he give the order to move.38 Their journey north was a long and painful progress through famine and plague-stricken lands, with the horses weakening from lack of forage or killed to provide food for the soldiers. As they crossed the boglands of County Tipperary they were harassed by Edmund Butler and his levies and everywhere along their route they were pestered by the starving Irish peasants who had been reduced to cannibalism.39

When they reached Trim in County Meath they rested for four days. The Ulster border was only thirty miles away. Here at last was the first flush of spring grass for their remaining horses and food for the men. So the gaunt and ragged band could pull itself into shape and march into Ulster as soldiers who had completed a mission.

It was time for Robert Bruce to return to his kingdom. Leaving many of his men with his brother Edward, he sailed for Scotland with the Earl of Moray while the passage of the seas was still open, landing late in the month of May 1317.40

As soon as it had been known in England that Bruce was intending to join his brother in Ireland, Edward II and the Earl of Lancaster, representing the Lords Ordainers, agreed to mount an invasion of Scotland, but the relations between them were not conducive to efficiency. According to a contemporary, ‘Whatever pleases the Lord King the Earl’s servants try to upset and whatever pleases the Earl the King’s servants call treachery: and so … the Lords by whom the land ought to be defended are not allowed to be of one accord.’41 In the event, the Earl of Lancaster and the barons of his party assembled their forces at Newcastle in October 1316 to await the arrival of the King. But the King had not forgotten Lancaster’s refusal to join him in 1314 and took his revenge by failing to appear. The Earl of Lancaster returned home in dudgeon and the troops were disbanded.42

The Earl of Arundel, however, hearing that James Douglas was to hold a housewarming on the completion of his hunting lodge at Lintalee in the forest of Jedburgh, gathered together his followers, each armed with a wood-axe, and with a number of other knights and esquires who wished for action, set out, several thousand strong, with the intention of cutting down the forest and destroying the lodge. But Douglas had enough warning of their coming to muster fifty mounted men and a great body of archers, for which that part of the country was famous.

At one point on their line of march the English had to pass between two woods which converged together to form a bottleneck. When he knew the enemy was near, Douglas placed his archers in ambush in a hollow on one side and his mounted men at the far end, and plaited the young birch trees along the edges of the ride so that it was difficult for a horse to break through. Then, as the English closed together to enter the narrowing way and had almost reached its end, he gave his war cry of ‘Douglas, Douglas’. The archers poured their arrows into the crowded flanks of the English cavalry and Douglas and his horsemen charged them head on with such force that the leading knights were bowled over and their horses, struggling and kicking, and those behind which had been brought down by the hail of arrows created such confusion that the English turned back into the open space behind and fled in panic.

Their van had been led by Sir Thomas Richmond, whose custom it was to wear a fur hat around his helmet. He was borne down at the first onslaught, and before he could rise Douglas had jumped from his horse, slain him with his dagger and taken his fur hat to wear as a token.

Three hundred of the enemy had missed their route and unexpectedly came across Douglas’s new lodge. Finding it unoccupied but with provisions all ready for his feast, they sat down to eat, thinking that he would be too much engaged elsewhere to disturb them. But his success had been so swift that he came back among them while they were still at table, and few survived.43

Another party of English knights who, after the disbanding of the army at Newcastle, sought action against the Scots, took ship and sailed north into the Firth of Forth. The sheriff of that area, when he saw the ships approaching, gathered a force of five hundred men and as the ships sailed along the coast kept pace with them on the shore to prevent them landing. But the ships beached at Inverkeithing near Dunfermline before they could come up with them and disembarked so many knights that the defenders, seeing them in formation, lost heart and began to stream away inland. William Sinclair, Bishop of Dunkeld, with sixty horsemen met them as they fled. He asked the sheriff what was their hurry. The sheriff replied that the English had landed in such force that they could not oppose them. At this the bishop, after saying contemptuously that he should have the gilt spurs hewed from his heels for such cowardice, called out ‘Let him who loves his King and country turn smartly and follow me.’ With that he cast off his bishop’s robe, beneath which he was in armour, and seizing a stout spear rode towards the enemy.

The Scots, shamed into action, drew up behind him. When they neared the English the bishop, who was a big and mighty man, cried out ‘Now spur your horses, men, and we shall override them’, and like an avalanche they charged the opposing ranks and scattered them in confusion. Many went down before the Scottish spears and others retreating to the ships crowded the nearest so thickly that they overturned and all were drowned.

When Bruce was later told of how the bishop saved the day, he took him in his arms and called him ever after ‘my own bishop’.44

The failure of his armed forces decided Edward II to enlist the weapons of spiritual warfare. His opportunity now arose. Pope Clement V, his country’s friend, had died soon after Bannockburn. For two years the electoral college had been unable to agree on a successor. At last in August 1316 their choice had fallen on John XXII, a Frenchman from the English fief of Guienne. The abiding ambition of the new Pope was to launch a crusade against the infidel.45 The English envoys at his Holy See in Avignon, in the absence of any Scottish representatives, who were debarred by the wholesale excommunication pronounced by his predecessor, easily persuaded him that only the obduracy of the Scots prevented them from offering the whole of their military might for the recovery of Jerusalem.

Accordingly he issued the bull ‘Vocatis Nobis’ commanding a two-year truce between Scotland and England, and sent a powerful embassy to London under the Cardinals Guacchini and Luca to see that the papal instructions were delivered to both parties. The cardinals arrived in the autumn of 1317 and handed over to Edward II the sealed letters they had brought with them. At the same time, they despatched two envoys, the Bishop of Corbeil and the Archdeacon of Perpignan, under safe conduct to the Scottish King with similar letters for his perusal.46

A confidential report made to their masters on the completion of their mission has an especial interest, for it is the only contemporary account of a meeting with Robert Bruce in person. From it emerges the portrait of a man of great charm and dignity, calm, assured, with a lively sense of humour and a beguiling courtesy.

He received them, they wrote, with smiling affability. No man, he declared, was more anxious to secure a true and lasting peace nor was more conscious of the Holy Father’s benevolence in making efforts to achieve it. But when they handed him the letters he pointed out that they were addressed to ‘Our dearest son in Christ, Edward II, illustrious King of England, and to our dear son, the noble Robert Bruce, acting as King of Scots’. ‘There are,’ he said mildly, ‘several gentlemen in Scotland who have the name of Robert Bruce.’ It would have been highly indelicate for him to open letters which might be intended for one of these. Only if they had been addressed to the King of Scots would he have felt sure that they were meant for him, and since they were not he had no option but to refuse them.

The envoys, in some confusion, pleaded that the Holy Father could not employ denominations which committed him to one side or another in a temporal dispute. ‘But that,’ said the king, ‘is exactly what he has done by depriving me of the title of King which is acknowledged throughout my realm and by which I am addressed by foreign rulers. Our Father the Pope and our Mother the Church of Rome would seem to be showing partiality among their own children. If you had brought letters addressed in this manner to other kings you might well have received a more savage reply.’

When they begged him to waive protocol and in the interests of humanity bring a halt to hostilities, he answered that this was a matter for his parliament and he could not expect their decision for some time. His tone had remained friendly but firm throughout the interview, but when they retired from his presence the forcible expression of his councillors left them in no doubt of the indignation aroused by the insult to their King.

They returned therefore to the cardinals with the sealed letters undelivered. But the cardinals were unwilling to credit the discouraging report of their envoys and appointed another emissary. The unfortunate man they selected was Adam Newton, Superior of the Berwick Franciscans. Well aware of the delicacy of the situation, he prudently left the papal communications at his friary until he should be confirmed of a safe conduct. After a hazardous journey he found the King of Scots in a wood near Old Cambus, a hamlet some twelve miles from Berwick, busily engaged in preparing siege engines for an assault on that city. Newton obtained a safe conduct from Sir Alexander Seton, the King’s deputy seneschal, returned to Berwick for his papers and once more made his way to Old Cambus.

He was refused a royal interview but his letters were delivered to the King who, observing that they were still not addressed to the King of Scotland, had them handed back with the brusque rejoinder that so long as his royal titles were withheld he would accept no truce but would make himself master of Berwick. Fearful of the fury of his superiors, the friar nerved himself to declare in public, before a gathering of barons and their followers, that the Pope demanded an instant application of a truce. A menacing growl of anger greeted his pronouncement and he was with difficulty hustled away from the place and ordered to find his own way home.

His troubles had not ended. On his road to Berwick he was waylaid by four armed ruffians, robbed of his papal documents, among which were bulls excommunicating the King of Scotland, stripped of his clothes and sent naked on his way. ‘It is rumoured,’ he wrote in a letter addressed to the cardinals, ‘that the papers entrusted to me are now in the possession of King Robert.’

The failure of the papal efforts and the news of the Scottish preparations against Berwick determined Edward II to order a mobilization for the protection of that town, but he was forestalled by Bruce. For some time the citizens of Berwick and the military had been at odds. In June 1317 Edward II received a complaint that the commandant was defrauding the Treasury by ‘drawing double pay for his retinue, starving the garrison, committing peculations in stores and totally neglecting the King’s interest’.47 In consequence Edward handed over the control of the town’s defences to the mayor and burgesses to be administered on an annual grant of six thousand marks. 48

Inevitably disputes arose between soldiers and burgesses. Among the latter one Peter Spalding was much offended by the insults he received from the military on account of his marriage to a Scotswoman. In revenge he sent word to Sir Robert Keith, Marischal of Scotland, to whom his wife was related, that, on a certain date on which it was his turn to keep watch over a section of the wall, he would admit the Scots. Sir Robert took the message direct to the King, who decided to risk the possibility of a trap.

Sir Robert was ordered to keep his information secret and to assemble his men at Duns Park. To him there the King would send James Douglas and Thomas Randolph with a small body of picked men, and only then was he to reveal the plot to the other two leaders.

On the night of 1 April 1318 Douglas and Randolph with their scaling party left their horses at Duns Park and marched through the darkness to where Spalding was waiting. There they set their ladders and mounted the walls unseen. Their orders were to hold that part of the walls with their main body until Bruce should arrive with reinforcements, but to send a few throughout the town to cause panic.

When daylight came the prospect of plunder proved too great for Douglas and Randolph to be able to restrain their men, who dispersed through the streets pillaging and killing. This almost proved fatal to the enterprise. Many of the citizens escaped to the castle with their arms and swelled the garrison. By noon, the governor of the castle, Roger Horsely, seeing the holding party on the walls reduced to a handful, made a sally with his increased forces and nearly overwhelmed them. Never was the disproportionate effect that could be achieved by veteran champions more clearly shown than on this occasion. Almost single-handed Douglas and Randolph repelled the attack, ably assisted by a new-made knight, Sir William Keith of Galston, whose name has come down to posterity for his action that day. The English were driven back to the castle.

Bruce arrived with his army soon after, secured the town and within a short time starved the castle garrison into surrender.49 Conscious of the immense trading value of the greatest seaport in his kingdom, Bruce made an exception from his policy of demolishing all captured fortresses. He repaired and improved the battlements: provisioned the castle with stores for a year and placed town and castle under the command of his son-in-law Walter Stewart. Neither he nor his son-in-law had any illusions that the English would allow Berwick to remain undisturbed. Walter Stewart sent for his friends and followers till he had with him, besides archers, spearmen and crossbowmen, five hundred gentlemen who quartered the arms of the Stewart. He enlisted also John Crab, a Fleming and an expert in the construction of siege weapons, who assembled for him along the ramparts catapults both large and small for the discharge of huge stones or iron darts and installed hoses to emit Greek fire.50

When, by May 1317, these precautions had been put in train, Bruce took his army south, captured the castles of Harbottle, Wark and Mitford and then drove deep into Yorkshire, burning Northallerton, Boroughbridge and Knaresborough.51 Ripon was spared on the promise of a thousand marks. Six burgesses were taken as hostages to ensure payment.52 Two years later the unfortunate wives of these men, when the bulk of the debt was still outstanding, petitioned Edward II to compel their fellow citizens to make good their undertaking so that they could once more enjoy the comfort of their husbands.53 The plunder from this expedition was very great especially in terms of livestock. ‘They made men and women captive,’ says the Lanercost Chronicle, ‘forcing the poor folk to drive a countless quantity of cattle before them, carrying them off to Scotland without any opposition.’54

The Archbishop of York responded to this incursion into his diocese by proclaiming once more the excommunication of the King of Scots. His opening salvo was followed by a powerful barrage from the Pope. In June 1318 he published a sentence of excommunication not only against Robert Bruce but all his accomplices. Scotland was placed under an interdict, and in September it was ordered that in every church throughout England a service of commination should be held thrice daily in which curses should be pronounced against Bruce, Douglas and Randolph.

NOTES - CHAPTER 14

1 Dickinson, 126

2 Vita Edwardii, 57

3 Lanercost, 210–11

4 ibid., 212

5 ibid., 213

6 Walsingham, 143

7 Cal. Doc. Scots, ii, 1260, 1277, 1763; Rishanger, 414; Stevenson, ii, 281

8 Lydon, 118

9 ibid., 119–20

10 Barrow, 434

11 Frame, 4

12 Barbour, 237, Pluscarden, 187

13 Dickinson, 128

14 Lanercost, 212

15 Barbour, 240–42

16 ibid., 245–6

17 ibid., 254–8

18 Lydon, 121

19 Barbour, 259–60

20 Cal. Doc. Scots, iii, 451; Vita Edwardii, 61, 67

21 ibid., iii, 448

22 Lanercost, 213–15

23 ibid., 216

24 Cal. Doc. Scots, iii, 452, 470, 477, 480

25 ibid., iii, 470

26 Barbour, 260–62

27 ibid., 263–6

28 Cal. Doc. Scots, iii, 527

29 Lanercost, 216

30 Barbour, 268

31 Barbour, 269

32 Nicholson, 94

33 Barbour, 269

34 ibid., 270–73

35 Lydon, 118

36 Frame, 23

37 ibid., 34–5

38 Barbour, 275

39 Frame, 36 and footnote 26

40 Lanercost, 218

41 Vita Edwardii, 75

42 Lanercost, 217

43 Barbour, 277–80

44 ibid., 282–5

45 Vita Edwardii, 78

46 Foedera, ii, 340

47 Cal. Doc. Scots, iii, 553

48 ibid., iii, 555

49 Barbour, 287–92

50 Barbour, 293

51 Lanercost, 220–21

52 Cal. Doc. Scots, iii, 707

53 ibid., iii, 858

54 Lanercost, 221

* cf note IX