YOSEF IBN AVITOR

(c. 940–after 1024)

YOSEF IBN AVITOR was born in Merida into a prominent Jewish family that had lived in Spain for generations. He studied in Cordoba under the renowned Talmudist Moshe Ben Hanokh and soon became known as one of his most precocious students. Ibn Avitor went on to serve as a religious authority for many Spanish Jews, who turned to him with questions regarding halakha, or religious law. He is, though, best known for his poetry. Just as his responsa show the influence of the Babylonian academies, so, too, his liturgical poetry preserves the then six-hundred-year-old Eastern tradition that went back to the work of Yannai, Qallir, and especially Sa‘adia Gaon. An archaizing religious poet of what Fleischer calls “titanic powers,” Ibn Avitor was prolific and ambitious. Some four hundred of his poems have survived (most still in manuscript), and he seems to have attempted almost every sort of pre-Andalusian liturgical mode. According to Ibn Daud’s Book of Tradition, the twenty-year-old Ibn Avitor also composed an Arabic commentary—probably an abstract—of the Talmud for the library of the Andalusian caliph, al-Hakam.

By all accounts he was difficult. Well aware of his worth, and who his forefathers in Spain had been, Ibn Avitor was haughty, rash, and—at times—fanatical. These traits appear to have cost him the position he’d long coveted: head of Cordoba’s Jewish academy. The bitter intra-Jewish politics of that affair involved the caliph as well, who—after the community had “excommunicated . . . and banned him”—advised Ibn Avitor to leave Spain. “If the Muslims were to reject me,” said the caliph, “in the way the Jews have done to you, I would go into exile. Now betake yourself into exile!” The disgraced poet made his way to North Africa, Egypt, and then Palestine and Babylonia, before backtracking and settling in Egypt. There he resumed his life as a teacher and religious authority. He died, it appears, in Damascus. The secular poems translated here—three of just a handful of his poems that incorporate elements of the new Andalusian style—were most likely written in Egypt. The final poem, a hymn for the New Year, gives powerful and archaic expression to the poet’s cosmic, quasi-mystical perspective and his Blakean sense of majesty in creation’s detail.

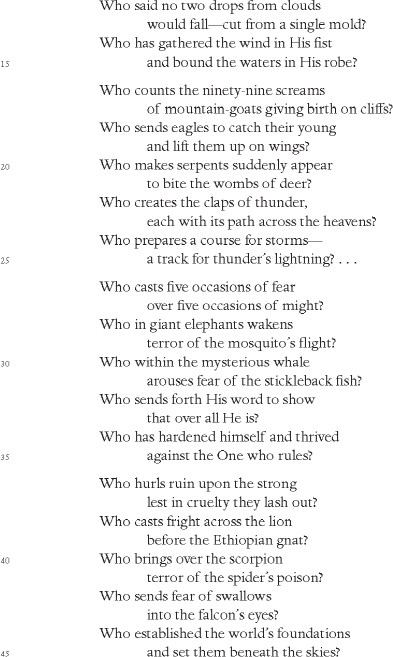

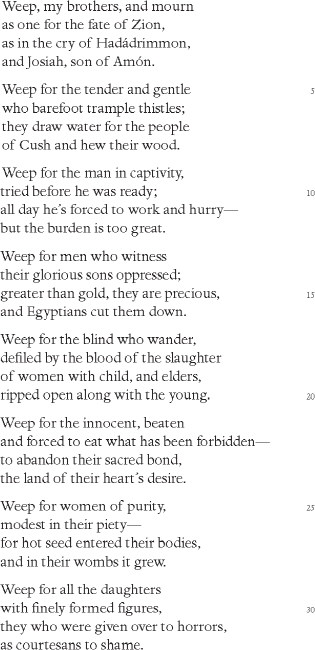

LAMENT FOR THE JEWS OF ZION

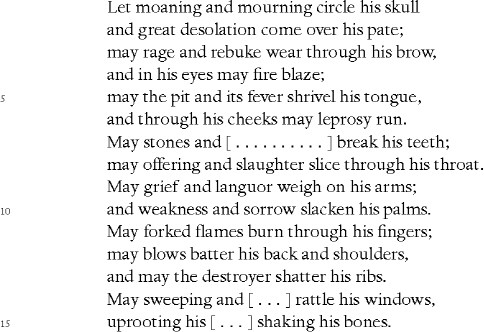

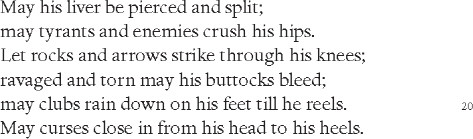

A CURSE

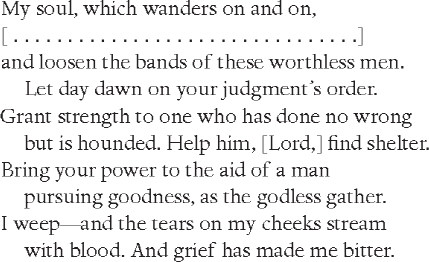

A PLEA

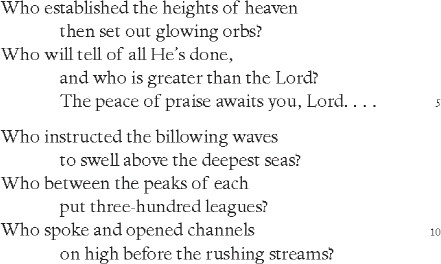

HYMN FOR THE NEW YEAR