MESHULLAM DEPIERA

(early thirteenth century–after 1260)

MESHULLAM DEPIERA lived his entire life in northeastern Spain and never experienced Muslim rule. Born, it seems, and raised in Gerona, he was also known by the Catalan name of Envidas and most likely spoke the regional language, which was close to Provençal. He was one of the most daring and innovative of the Spanish-Hebrew poets, and his poems indicate that the man was every bit as difficult as his work: “I admit there’s a little strangeness in me,” he confesses in one poem, but adds, “though my heart goes out to my friends in need.” Perhaps because he was marching to the sound of a distinctly un-Andalusian drummer, his poems enjoyed only minimal circulation after his lifetime (among some of the later poets) and then disappeared after the seventeenth century. They were rediscovered in the 1920s and published in a critical edition in 1939.

The fifty poems of Meshullam that have come down to us are characterized by their density and at times obscurity, their supple manipulation of the qasida form, their innovative use of rabbinic as opposed to biblical diction, their complication of perspective, and—in their polemical mode—their subtle satiric strategies. It is possible that the torque of Meshullam’s verse was influenced by the troubadour poets of Provence and their trobar clus style; others suggest that some of his abstruseness can be traced to his qabbalistic training. (Meshullam was a member of Spain’s first qabbalistic circle, which took shape around Nah-manides in Gerona, though his poetry rarely mentions the other members of his group or their mystical doctrine.) Not all his work, however, is obscure; on the contrary, some consider him the first Hebrew medieval poet to break free of the Arabic literary conventions and speak “freely” in his verse. Unburdened by the literary protocol of the court context, Meshullam was writing to please himself alone. And where he does preserve the classical conventions, he often significantly extends their range or undermines them, so that their surface can be deceptive. There is, for instance, a pronounced antisecular strain throughout his verse: he wrote many poems against Maimonides’ Aristotelian Guide for the Perplexed, which he considered blind to the mysteries of Scripture; and in “How Could You Press for Song” he pours forth scorn for the grammarians. Fleischer notes that this marks a sea change in Hebrew literature, as the study of Hebrew had always been prized and poems were often written in praise of the language and its intricacies. That said, Meshullam was not at all averse to worldly pleasures and, while without doubt a God-fearing man, he was perfectly willing to give vent to his impatience with excessive piety. Schirmann notes lines such as: “Jewish faith is ablaze in me, / though I do not weaken my heart with fasts” and “My prayer is pure, though it isn’t long, / and I offer it softly, not with a cry.”

It is difficult to make a selection of Meshullam’s work that does him justice: most of his poems are long, and choosing one over another would exclude critical elements of his poetry and its vision. Included here, then, are three short poems and excerpts from a number of other poems treating topics such as the nature of poetry, its power and mystery, the limits of linguistics, and the true goal of study.

THE POET

ON A NEW BOOK BY MAIMONIDES

BEFORE YOU TAKE UP YOUR PEN

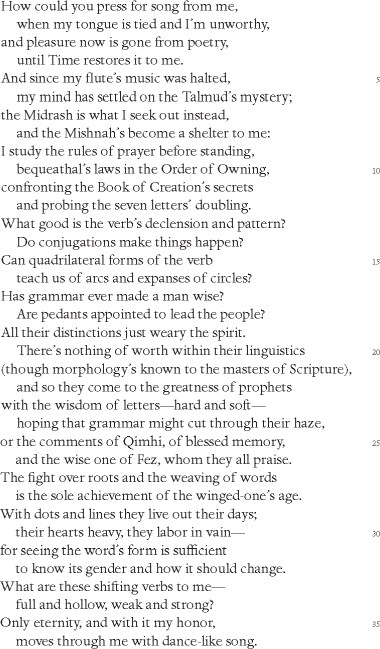

HOW COULD YOU PRESS FOR SONG

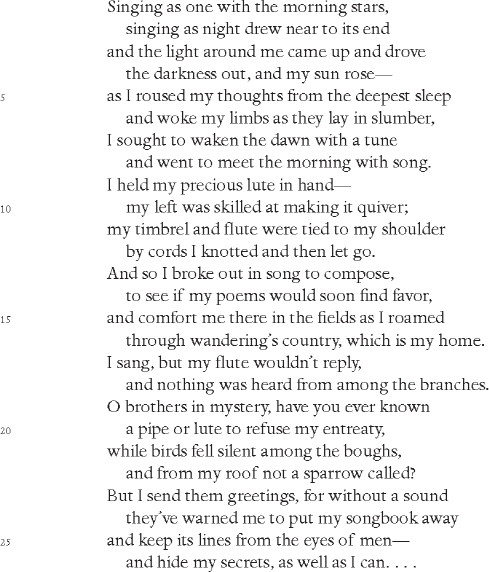

AS ONE WITH THE MORNING STARS