QALONYMOS BEN QALONYMOS

(1286–after 1328)

One of the most versatile Hebrew translators of the middle ages, QALONYMOS BEN QALONYMOS was responsible for the rendering of at least thirty works from Arabic into Hebrew—many by Ibn Rushd—and he also translated from, and at times into, Latin. Born in Arles in 1286 to an illustrious family that saw itself as descended from the biblical King David, he was raised in relative comfort. Later in life, however, he suffered along with the rest of the Jewish community during the reign of Philip the Fair, who exploited the Jews in every way for financial gain. In 1316 Qalonymos completed his translation of the Iggeret Ba‘alei HeHayyim (The Epistle of the Animals), by the Iraqi scholars known as the Brethren of Purity, and during the following years he seems to have traveled around Provence and Catalonia. In the late fall of 1322 he finished his major work, Even Bohan (Touch-stone). He was thirty-five years old. Shortly thereafter he was summoned to Italy, where Robert Manjou, duke of Provence and king of Naples, had assembled a school of translators. Qalonymos spent several years in the king’s employ in Naples and Rome, translating scientific works from Arabic and Hebrew into Latin. (He was known there as Maestro Calo.) While in Italy he met the greatest Italian-Hebrew poet of the day, Immanuel of Rome, who, in his Mahberot Immanu’el, writes admiringly about Qalonymos’s tremendous learning and the accomplishment of his rhymed prose. By 1328, Qalonymos was back in Arles.

Even Bohan reflects both the poet’s arrival at midlife (the age of account) and the historical events through which he lived. Its death-obsessed later chapters are accordingly dark, gloomier even than Yedaya’s Behinat ‘Olam. The first part of Qalonymos’s work, though, consisting of a series of descriptions of the Jewish community and its “types,” contains an unusual mix of humor, biting satire, and resigned acceptance of the writer’s situation. Even Bohan is written in rhymed prose, and Qalonymos is explicit about his desire not to be considered a poet. In fact he singles out poets for some of the harshest treatment in his sketches:

There are those who take pride in poems they’ve made—which make them brave—as they’re filled with subjects abstruse and grave. Before the people’s eyes they rise, then strut about with their heads held high, speaking in riddles—and twisting the lessons of the wise. . . . On streets and alleys throughout the town, toe to heel, they prance around, like gilded doves, because they’ve found . . . in rhetoric’s ways some strange innovation to let them speak as no one has done. . . . And if they’re praised—to their faces—their eyes beam and give off rays. And then one says: ‘Blessed are you to the Lord! You’ve understood my every word!’ . . . And so I’ve observed: O you deep ones, over your heads in law and religion, you fritter away your days in a mission that’s neither a trade nor yields any wisdom. You dive through the depths, and work so hard, only to surface with worthless shards.

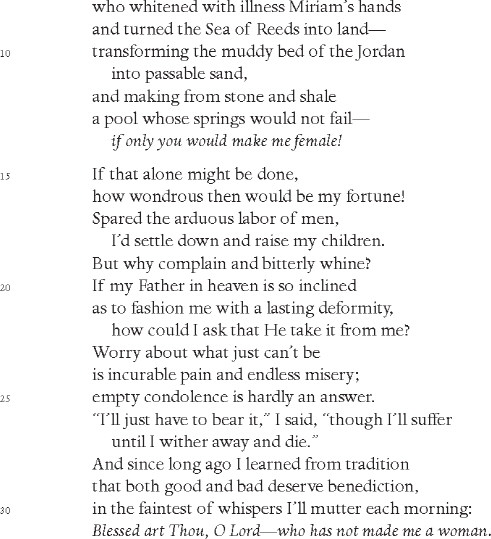

Also included in the first part of Even Bohan is a section in which the writer—who had been in the midst of a long confession of his sins and a Job-like indictment of the day he was born—suddenly breaks off and offers the surprising prayer translated below. Again, while the Hebrew original is in rhymed prose rather than lines of metrical poetry, or even the quasi-biblical parallelistic free verse we’ve seen elsewhere, it is offered here because of its excellence and its prominence in the Hebrew canon. Scholars have struggled in their reading of this section, seeing it as an “odd,” “amusing,” or “parodistic” insertion; in fact, grappling with the passage in the context of Qalonymos’s work as a whole reveals it to be part of Even Bohan’s quasi-carnivalesque critique of the author’s own culture.

ON BECOMING A WOMAN