1

• • •

The Basics

Chinese medicine is grounded in the philosophies that evolved from an ancient culture deeply sensitive to the rhythms and relationships of nature. Early observers tried to make sense of human existence and our relationship to the never-ending cycle of birth, growth, maturity, decline, and death. They understood human beings to be small reflections of the larger cosmos, connected energetically to the movements of Heaven and Earth, and therefore impacted by the phenomena of their natural surroundings.

In the very early days of the development of Chinese medicine, the priority of care was to prevent illness. If one of the farmers in the village became ill he was unable to work the fields, unable to provide for his family, and ultimately unable to be productive in the community. The early medical practitioners provided care during acute illness or injury, but their primary role during those early days was to be a teacher to the community, making recommendations regarding diet, exercise, and other lifestyle choices. Preventing illness and maintaining the health of the population was crucial.

The early practitioners recognized that, just as the seasons of the agricultural year changed, so too were there natural phases of life for the men, women, and children of their community. Priorities and responsibilities changed as individuals moved through their lives. A young woman of childbearing age was, of course, treated differently than the grandmother of the family. A young man laboring in the fields had different health concerns than the village elder.

Guided by principles learned from observing nature, a system of thought developed that made the correlation between the cycles and interactions of nature and the stresses experienced by human beings. When the soil is fertile and moist, with appropriate periods of sunlight and warmth the crops thrive and yield a good harvest, and the population is well nourished. If, on the other hand, there is a drought, or floods, or the temperatures are too hot or too cool, the crops become diseased, wither, or even wash away. A light wind might gently rock the trees, their slight movement enough to aerate the soil around their roots, but too much wind breaks branches or uproots entire trees.

Likewise, if we humans have access to nourishing food and clean water and live in a sheltered environment with resources to manage the unpredictability of life, we have more freedom to live meaningful, healthy lives.

The philosophy from which Chinese medicine derives is not merely intellectual but pervades traditional Chinese culture, as is evidenced by the recognition of interrelationships among humanity, nature, and the cosmos. On the other hand, in modern Western culture, our philosophy tends more toward breaking things down to their smallest component parts to fully define and understand the individual pieces of the whole. These different ways of viewing the world pose a challenge for Westerners who are trying to understand Chinese medicine.

Our initial exploration in this primer includes an introduction to the vocabulary that describes the nature of illness; the Chinese understanding of the energetic circulation in our bodies; and the interconnectivity we have with our environment.

The Vocabulary

Much of the language of Chinese medicine is metaphorical. The words defining imbalances in the human body are the same as the words we use to describe the phenomena of nature. Wind, Cold, Damp, and Heat are among the terms commonly used to describe imbalances in the body. Extremes of these factors lead to illness, just as extremes of climate damage crops. We have no control over the climate, but we human beings can make choices that strengthen our abilities to accommodate the changes that occur in our lives. A moderate climate is critical for abundant crops; if we maintain our physical health by making moderate choices in our lifestyle, the “climatic” factors are less likely to interfere with a productive, healthy life.

The Pathogenic Factors—Wind, Cold, Damp, and Heat

The terms Wind, Cold, Damp, and Heat can be literal descriptions of external climatic factors penetrating the body. For example, when we get sick after working outside on a cold, windy day, we have acute “Wind-Cold” with sneezing and a runny nose. The terms can also describe the effects of food that we eat: we get a sharp stomachache after eating too much watermelon, a food that is described as energetically Cold in nature. Symptoms of Heat, such as the red, swollen, painful joints typical in rheumatoid arthritis, are described as Hot Bi/Obstruction syndrome. Or we feel heavy and lethargic after eating pasta with a cream sauce, both of which contribute to Dampness.

The terms are also metaphors for the emotional challenges we encounter in life. The nature of Cold is to restrict movement; the nature of Dampness is to make things heavy. If we wake up depressed, weighted down by responsibility, perhaps fearful of facing the day, our condition might involve aspects of Cold and Damp. On the other hand, someone prone to angry outbursts most likely has a condition of excessive Heat.

The Su Wen acknowledges many causes of illness. We can become ill from internal factors related to poor diet, insufficient exercise, or emotional patterns. We can become ill from external factors that are environmental or climatic in nature. And we can be born with an illness.

Regardless of cause, the terms Wind, Cold, Damp, and Heat can describe acute illnesses or long-term, chronic, degenerative conditions. In the West, despite our technological approach to medicine, we commonly say we have “caught a cold” or are feeling “under the weather.” These statements acknowledge that we are indeed connected to the environment, that we are vulnerable to the climate, and that this vulnerability can affect our health. When we keep this in mind, the language of Chinese medicine can perhaps feel a bit less foreign.

The Wind That Causes Hundreds of Diseases—Inevitability of Change

In the Su Wen we are told that Wind is the cause of all disease. This Wind can be literal, as in the wind caused by changes in atmospheric pressure, bringing with it a change in temperature and/or pollens and other allergens. But Wind is perhaps more powerfully understood as a metaphor for change. How well do we accommodate the changes in our environment, the weather, or the transitions of our lives? Do we suffer allergies when the seasons change? Do we resist the aging process, insisting on maintaining the same interests, relationships, and responsibilities as we had thirty years ago? As we often hear, the only constant in the universe is change. Everything is changing all the time. The better able we are to move gracefully with these changes, the less stress we experience and the healthier we can be.

Wind moves. It can blow in any direction. The physical signs and symptoms of Wind imply some kind of movement, be it the movement of fluids reacting to allergens and producing a runny nose and teary eyes or the movement of a person being fidgety and unable to sit still. Wind can manifest as a superficial, acute condition that causes us to shiver or have a muscle spasm. Or it can be Wind Bi/Obstruction syndrome, a condition of radiating or traveling pain. There can be twitching in the eyelid, dizziness, or high blood pressure. At a deep, chronic level, neurological conditions such as the trembling of Parkinson’s disease or the seizures of epilepsy are identified as Wind conditions.

When the term Wind is used in conjunction with the terms Cold, Damp, or Heat, it typically describes a relatively acute condition. When used otherwise—for example, Internal Wind or Liver Wind—it refers to illnesses that are more chronic in nature.

Cold—Resistance to Moving with the Winds of Change

The second major culprit in creating illness is Cold. The earliest major tradition of Chinese medicine is recorded in the Shang Han Lun—the Treatise on Injury by Cold. An early pictograph for the term Cold is the representation of a cultivated farm field and a house with a teardrop coming out of it. The meaning: Cold is anything that prevents us from doing the things we need or want to do. Cold restricts movement; it blocks energy. It expresses a hesitation to make change. It might be from emotional causes or from traumatic injury. It can be from eating and drinking icy, cold foods and drinks. Or it can simply be from being chilled to the bone on a frigid winter day.

The study of how Cold affects the body was significant enough to have a whole tradition dedicated to it. How did the pathology initially enter the body? What were the routes it took to penetrate deeply into the physiology? What could break up the blockages it was causing? How could the body release it?

The channel systems through which energy circulates allowed early practitioners to map out the routes by which pathogenic factors penetrated the physiological defenses of the immune system. By understanding how and where the pathogenic factor had entered—through the skin? through the gut? the lungs?—theories were developed as to how to move the Cold back out again. The Shang Han Lun tradition developed a sophisticated understanding of the etiology and progression of disease, and how to treat it by ultimately expelling the pathology to the exterior. Indeed, Chinese medicine holds the belief that if acute illness is properly treated by bringing the pathology to the exterior instead of suppressing it and pushing it more deeply into the physiology, we will be less likely to develop chronic degenerative disease.

Cold constricts. It resonates with deep parts of our anatomy, where energetic movement is slow—for example, in the bone and the marrow. Signs and symptoms of Cold conditions can include sharp, gripping, or fixed pain, aversion to cold, fear, feeling cold to the touch, or poor circulation.

Acute viral conditions such as the common cold are attributed to Wind-Cold. For acute Wind-Cold the treatment principle is to “release to the exterior” through sweat and expectoration. The simplistic treatment strategy is to create warmth—take a hot bath, drink a warming herbal tea, or put a hot compress on the area of pain.

A more complicated condition than acute Wind-Cold is chronic Cold—for example sharp, chronic pain in the lower back—or “Cold in the Uterus,” causing painful menses or infertility. In this case, Cold has penetrated deeply into the anatomy and requires a more sophisticated treatment strategy.

Viruses in general can be described as a Cold pathogen. They are able to migrate into deeper levels of the body, especially into the lungs and the liver, which both offer a blood-rich environment for the virus to take up residence. Some practitioners believe that many autoimmune conditions, such as multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis, are the result of a virus that the body has been unable to expel. The herpes virus has evolved with human beings over such a long time, it might almost be a part of our DNA.

Damp—Heaviness and Lethargy

Dampness can be created by external or internal factors. In the agrarian culture of China, farmers waded for long hours in the rice paddies, and many of them developed a condition known as leg Qi. One of the great practitioners of Chinese medicine, Hua Tuo, described a process of Dampness being absorbed through the feet and moving upward into the legs, causing heaviness and aching in the lower limbs. These words—heaviness and aching—are most descriptive of a Damp condition. Dampness can be physical discomfort, as in leg Qi, or it can be the lethargy we experience when the weather is heavy with humidity, or when we eat sweet, heavy, or sticky foods such as bagels and muffins, hard cheeses, rich sauces, or cookies and cakes.

Dampness weighs things down. It is heavy. It sinks. It tends to accumulate in the lower region of the body, perhaps as edema, with fluid swelling in the legs, or in the intestines, manifesting as diarrhea. As a chronic condition, Dampness is particularly insidious because it moves slowly and does not show itself with dramatic symptoms until it is well advanced. Emotionally, Dampness leads to indecisiveness.

If Dampness lingers in the body for very long, the body begins to generate Heat in order to dry it out. When Dampness and Heat combine, the condition becomes more complicated. Like reducing a sauce on the stovetop, the Heat causes the Dampness to thicken. It can become phlegm. Phlegm can manifest as a mass or nodule, and with the involvement of Heat, which invigorates its movement, the phlegm can be deposited anywhere in the body—in the flesh as lipomas; in the joints, ultimately leading to arthritis; on a gland as a nodule; or even in the brain, causing confused, dull thinking.

Dampness is associated with fungal conditions. Fungus grows best in a moist, dark environment, which in the body is reflective of the bones, spine, and brain.

Signs of Dampness are a thick, sticky coating on the tongue, a slippery pulse, or oily skin. Addiction to carbohydrates is also an indication, and consumption of such foods can lead to parasitic infestations.

Heat—Bringing Urgency to Change

In the theory of pathogenesis discussed in the Shang Han Lun, Heat is seen as a physiological response to the pathogen of Cold as it enters more deeply into the body. Ideally the body’s defenses are strong enough to expel the Cold soon after exposure. If it fails at this task, at a certain point the body begins to generate Heat to try to neutralize or break up the Cold. Most commonly, this transition occurs in the region of the chest.

For example, someone catches Wind-Cold. He is sneezing and feels a little chilled, and his nose is running with clear fluid. The discomfort is not bad enough, however, to make him stay home from work. He busies himself out and about, comes home, goes to bed, and wakes up the next morning with a bad sore throat and cough. He has taxed his immune system too much and now the external pathogenic factor has penetrated more deeply into his body. Maybe his cough produces thick yellow phlegm, a sign that Heat is being generated. Maybe he feels feverish. In any case, the transition from Wind-Cold to Wind-Heat has occurred. At this stage, it is still an acute condition. The treatment strategy is to release to the exterior through sweating and expectoration. Because the pathology has now penetrated more deeply into the physiology, it may also come out through urination. From a Western point of view, this transition toward Wind-Heat is likely to manifest as a bacterial infection in the sinuses or chest.

Heat invigorates. It is a natural physiological response to a Cold or Damp pathogenic factor to break up the constriction or accumulation and move it out of the body.

At this level, if the condition is improperly treated, the pathology begins to make its way even more deeply into the body. The modern widespread use of antibiotics and anti-inflammatory medicines is implicated in this deepening process. These pharmaceuticals have a cooling, dampening effect (that is, constricting and heavy and thus resonating with deeper levels of the anatomy). Since the Heat, or the bacteria being treated by the antibiotic, is in fact a response to an initial “injury” by Cold, the cooling effect from the drugs causes both the original Cold and the responding Heat to be pushed more deeply into the physiology. This process opens the door to the growth of bacterial colonies in the stomach and large intestine. At this deeper level, the Heat can begin to consume the fluids and blood that nourish the nerves, sinews, and the internal organs.

From the Western point of view, Heat is acidic. Many of the conditions with names that end in -itis (for example, tendinitis, arthritis, sinusitis, or bronchitis) fall into this category.

Further Complications of Heat

When Heat persists over time it dries out our fluids and damages tissues. In this hot, dry, desert-like environment, Wind begins to stir. When we are parched for nourishment our nerves and muscles become damaged, and conditions such as Wei/Atrophy syndrome develop, which can manifest as various neuropathies, including multiple sclerosis, ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Lou Gehrig’s disease), and Parkinson’s disease.

When they occur together, it can sometimes be difficult to determine whether Heat or Wind is the dominant pathology. A general guideline is that Wind has a greater effect on the body; it causes restlessness, spasms, or cramps. Heat can also affect the body, but it generally has a greater effect on the mind, the spirit, and the emotions.

Another deep condition of Heat damaging tissue is “Steaming Bone syndrome,” where the person feels heat emanating from deep within the body. Symptoms can include menopausal hot flashes and night sweats; swollen, bleeding gums; dry mouth; loose teeth; tinnitus; and urinary tract infections.

Tissues damaged during this process are called Fire Toxins, which can be likened to free radicals. These tissues no longer have the integrity to combine with fluids or blood and the continuing pathologic Heat flushes upward and outward because it can no longer be anchored. This is “Empty Heat,” the result of Full Heat having damaged the Blood, Fluid, or deep Essence of our physical bodies. This progression of Heat pathology yields symptoms such as hot flashes, or low-grade fevers that are worse in the afternoon or evening.

Heat as a Pathogenic Factor

As the rural, agrarian communities of ancient China were replaced by large and crowded cities, “pestilent” Qi and epidemics emerged. The medical understanding of Heat evolved to regard it as a pathogenic factor in and of itself, not just a response to Cold.

Heat spreads and consumes. The understanding of Heat as an internal pathology has its roots in the works of great practitioners such as Liu Wansu, founder of the school of Cooling and Cold, and Li Dongyuan (1180–1251 CE), founder of the Earth school. Both of these masters maintained that Internal Heat formed in the body because of dietary and emotional factors, especially because life was so busy and so driven by unfulfilled desires. With the emergence of contagious epidemics in large populations, however, a new understanding of Heat as a spreading external pathogenic factor developed during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The new theory was developed by the Wen Bing/Heat Disease school, which generated a sophisticated herbal approach to address this new health concern. The earlier Shang Han Lun understanding of Heat as a response to Cold or Damp was still valid, but the new Wen Bing school recognized that new challenges to health were evolving as the culture changed.

The Anatomy

Chinese medicine recognizes not only the physical anatomy of our bodies but also an energetic anatomy. Energy animates the movement of blood and fluids and allows for the proper function of the physical anatomy.

The Internal Organs

The same interconnectedness observed between nature and human beings is recognized within the body as well. The Internal Organs (Lung, Large Intestine, Stomach, Spleen, Heart, Small Intestine, Urinary Bladder, Kidney, Pericardium, Triple Heater, Gall Bladder, and Liver) have their individual responsibilities, which are understood to be similar to the responsibilities ascribed to them by Western medicine. Chinese medicine also ascribes significant interrelationships between the organs that are not so clearly recognized by Western thinking. These relationships are supported by energetic pathways, called channels or meridians, which support healthy function as well as carrying pathological factors. These channels course throughout the body, giving rise to the many relationships we see between the various organs and the channels themselves.

The Internal Organs can be individually afflicted with disease, or there might be imbalances of relationship that occur between the Organs. Any dysfunction at the level of the physical organs, however, will be preceded by blockages in the channels that interfere with proper physiological function.

Another group, the Curious Organs, includes the Brain, Marrow, Vessels (a controversial term perhaps referring to Blood Vessels or to a group of meridians associated with constitutional energy), Bones, Gall Bladder (the Organ that makes the link between the Internal and Curious), and Uterus (including the male genitalia). Unlike the Internal Organs, which are responsible for postnatal functions, the Curious Organs are the ones most involved in the evolutionary changes required for our species to continue living on Earth. (The Curious Organs are discussed in depth in chapter 7.)

The Channels

Each channel is a trajectory that allows for the movement of energy in the body. Channels have internal pathways, where they meet with their associated organs and communicate with other channels, and external pathways, where the trajectory carries energy into the arms or legs, or into the head.

For example, the Lung channel has an internal pathway that begins at the center of the abdomen. It travels downward to points adjacent to the navel and then upward to the breastbone and the actual organs of the lungs. This is the internal trajectory of the channel, and many important communications occur along the way. The external pathway emerges from the lungs at the hollow region in front of the shoulder and travels down the arms toward the thumbs.

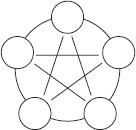

There are five channel systems of energetic circulation. The most popularly known are the Primary Channels, but there are also the Luo Channels, the Extraordinary Vessels, the Sinew Channels, and the Divergent Channels. These will be discussed in chapter 9, and subsequently in more detail in the introductions to groups of stones in the materia medica.

The Points

In modern Western practice, the channels and associated points used for treatment are given an organ name. The organ name is associated with a channel along which the points are located, and the points are given a number, for example “Stomach 36” or “Liver 3.”

Traditionally, the Chinese names of the points are descriptive of their function or anatomical location, and the names can actually change depending on the intention behind a treatment. Our Western naming and numbering of the points is for convenience of communication among practitioners. This method can, however, cause unfortunate confusion for clients. When a channel or point is mentioned, perhaps “Liver 8” or “Spleen 10,” clients are sometimes concerned that it is the actual organ of the liver or spleen being discussed, when, in fact, the practitioner’s intention is to affect the Blood.

How It Works—A Simplistic Explanation

Over the centuries of observation and experience, practitioners of Chinese medicine determined that certain points have particular functions. When an acupuncture point is stimulated by massage, a needle, an essential oil, or a stone, the immune system recognizes that something “foreign” is affecting the body. Resources gather and mobilize to the point to determine what action, if any, is required. Simply by virtue of the energy and blood that arrive at the area, the acupuncture point is stimulated, and its inherent functions activate.

The Modern Challenges to Health—Staying Healthy

The first nine chapters of the Su Wen are devoted to the discussion of the causes of disease. They emphasize that illness is the result of being out of harmony with nature and the changes of the seasons; our susceptibility to the external climatic factors of Wind, Cold, Damp, and Heat; and internal factors such as improper diet and destructive emotions. Life is very different in modern times than in ancient China, but the causes of illness are fundamentally the same.

External Factors

In modern Western culture, with the conveniences of technology, our ability to harmonize ourselves with nature has been seriously compromised. We leave air-conditioned spaces to enter the sweltering heat of a summer day, or we go out of our snug, warm homes to brave the frigid wintry night. Artificial lighting encourages us to ignore the natural rhythms of night and day, allowing us to study or watch television late into the night instead of going to bed and getting adequate sleep. Additionally, we are dealing with ecological and environmental pollutants that did not exist in ancient times. The air we breathe contains chemicals that are foreign to the physiology of our bodies. We absorb synthetic hormones from our plastic water bottles and electromagnetic radiation from our computers and cell phones. Because global travel is so prevalent, we can be exposed to pestilent factors from all over the world.

Humanity as a whole will evolve to adapt to these new challenges—it must in order to survive. We as individuals, on the other hand, may need to take action to counteract these new pathogenic factors if we want to live a healthy life relatively free from physical suffering.

Internal Factors

The Su Wen acknowledges that imbalances can result from improper dietary choices and excessive emotion. Again, modern life presents different challenges than ancient people faced. They had to contend with famine and malnutrition while we enjoy an overabundance of choice. We have food in plenty at our local grocery store, not just the produce and meat grown in the local region but offerings from all over the world. While poor agricultural practices have diminished the nourishing value of our food, the food-processing industry adds insult to injury by manufacturing substances that are not food and have little nutritional value.

Modern life offers tremendous diversity. Meeting people from very different cultural backgrounds is routine in many communities. We are bombarded by so much information from so many different sources that it is difficult to know what to believe, and difficult to make appropriate choices. With so many distractions, it is easy to be overwhelmed and to forget our personal priorities. And if we do get overwhelmed, it is easy to become emotionally imbalanced.

All in all, mainstream modern life is not very conducive to the cultivation of health. If we trust the ancient texts of Chinese medicine and want to be healthy, we must reacquaint ourselves with our interdependence with the natural environment. We can hope for a reasonably healthy life, with satisfying relationships and activities—even as we age—but accomplishing this is best achieved with appropriate, moderate lifestyle choices.