Level 11

They All Want You Dead

Video games are populated with a plethora of beings that want to kill you: aliens and androids, pirates and parasites, mercenaries and mushroom people. However, I realize not every video game features slobbering, sword-wielding enemies—often they use guns too!

Yes, yes. I realize that plenty of other video games use other forms of conflict, such as time, human competitors, or even the players’ own skill, to challenge the players. But I’m not talking about those types of games.1 As I flip back to Level 3, I am reminded of three types of conflict found in stories: man versus nature (like a hurricane or a giant white whale); man versus self (where the hero is struggling with an internal issue such as “where to go for lunch”2); and man versus man, or in the case of video games, man versus zombie or man versus ninja pirate or man versus hideous-alien-creature-made-from-the-skins-of-your-dead-crewmates.

Those are the types of enemies I talk about here. While zombies and ninja pirates and alien thingee enemies are great fun to design, you first need to follow this very important golden rule:

FORM FOLLOWS FUNCTION

Hey! I saw you trying to design that winged skeleton enemy without thinking about how he’s going to attack.3 Put down the pencil as I repeat myself because THIS REALLY IS VERY IMPORTANT:

FORM FOLLOWS FUNCTION!

You need to (not “would kinda like to”) determine the function of your enemies first. So many things are resting on the decisions in your design: how the programmer will code it, how the animator will build the rigging model, how the artist will texture it. These important enemy attributes are

- Size

- Behavior

- Speed

- Movement

- Attacks

- Aggression4

- Health

All these attributes, along with your level’s theme, will allow you to determine who your enemies are, what they will end up looking like, and how well they will work together when they are placed in the game. Having to redo an enemy character again and again and again is a big morale killer for your team and a huge waste of time and money.5

Sizing Up the Enemy

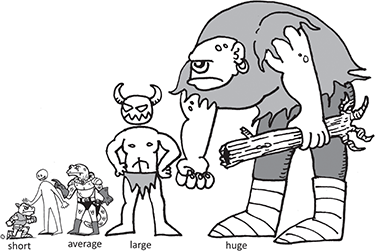

Speaking of huge, enemies come in a wide range of sizes:

Short enemies are no taller than the player character’s waist.

Average enemies are roughly the same height as the player character.

Large enemies are several heads taller than the player character.6

Huge enemies are at least twice the player character’s own size.

Gigantic enemies are so large that they can be completely seen only from a distance.

The size of the enemy will determine how the player will fight it. For example, a short enemy can be fought only by crouching or with a low attack like an upward sweep or radial spin attack. On the other end of the scale, a huge enemy with a vulnerable head can be reached only with a jump attack. Design your combat so the player character “fights his way up” the enemy: the player character should be able to hit an average enemy using a low or medium attack; the player character should be able to hit a huge enemy using a low, medium, or high attack; and so on.

Size also influences health. Larger enemies traditionally have more health (are harder to kill) than smaller ones. This might account for why many bosses are so darn big. Size will also dictate the enemies’ reaction to attacks. Hit a short enemy with a knockback attack, and he should go flying. Hit a large enemy with the same attack, and he may not even budge. You’d be lucky if a gigantic enemy even notices your attack, let alone reacts to it.

They say variety is the spice of life. I don’t know about spice, but I do know it is variety that keeps a player from getting bored. Size can influence a player’s emotions too. Defeating a huge enemy can make a player feel heroic, whereas defeating a short one can make him feel like a bully.

Bad Behavior

Now that you’ve determined size, ask yourself, what is the enemy’s behavior?

- How does the enemy move?

- What does the enemy do when in combat?

- What does the enemy do when he is hurt?

Answer these questions, and you will have the foundation to build robust enemies. When you are designing enemy behavior, the goal is to not have different enemy characters repeat the same behaviors. Even better, design your enemies’ behaviors to complement each other.

A patroller moves back and forth or up and down in a mechanical fashion. The path of movement can be more involved than this, but the movement is always predictable.

A chaser pursues a player if approached or some other condition is met. In many games, patrollers can turn into chasers when they see the player or the player attacks them.

A shooter is an enemy that fires a projectile. Shooting patrollers and chasers will fire at the player once they’ve been spotted. Due to the nature of the attack, this enemy will try to keep distance between himself and the player rather than engage him.

A guard is an enemy whose AI priority is to guard an item or location (like a doorway) rather than actively pursue the player. Guard behavior can be easily combined with chasing or shooting if the player manages to steal the item or get past the guard.

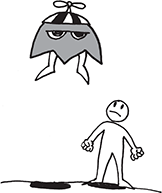

A flyer is an enemy that, well … flies. Flyers are aerial patrollers, but because the flying adds another dimension (literally) to the movement, these characters deserve their own classification. Flyers can swoop down to attack players, or they can fire projectiles from a safe distance. Flyers are more advanced enemies for the player to deal with because their movement and attack patterns can be difficult to predict. Players trying to attack flyers usually stop to target or make a jump attack.

A bomber is a flyer that attacks from above. Give the player warning that a bomber is above to drop down (or drop its payload) so it doesn’t come as a nasty surprise. In a game that uses a third-person camera, bombers can be difficult for a player to see as they fly above the player to attack.

A burrower is an enemy with an invulnerable state that allows him to get into an advantageous position to attack the player. The player must wait for the enemy to emerge before he can attack.

A teleporter is an enemy that can change position around the playfield. The player must attack quickly lest the enemy teleport out of harm’s way. The teleporter varies from the burrower in that the teleportation is instantaneous, giving the player no time to attack. Give your player a way to disrupt the enemy’s teleportation, such as a stun or another disruptive attack.

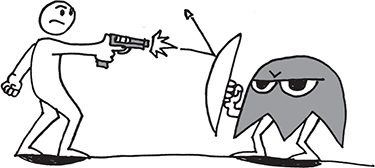

A blocker is an enemy that defends himself against the player’s attack with a shield or other defensive device. The shield can either be circumnavigated with an attack from another direction or elevation (such as from down low or from behind), or the player can disarm the enemy with a specific move or attack. Shields can make the enemy temporarily invulnerable, requiring the player to break the shield with a specific move or action, or wait around until the invulnerable state passes.

A doppelganger is an enemy that looks like the player; he moves, attacks, and uses AI that mimics the player’s own. Doppelganger enemies force players to use moves or weapons in an unusual manner in order to defeat “themselves.”

The goal of having all these different behavior types is to have enemies that complement each other. Enemies should “live harmoniously” with each other, creating interesting combat challenges for the players to solve.

Once you create enemy behaviors that work well together, it will create gameplay. In dealing with these enemy combinations, players will learn how to perform threat analysis. They’ll find that sometimes it’s easy to take out the weak enemies first and other times it will be better to tackle the deadlier foe and ignore the little guys. As a designer, you can force the player to make these kinds of interesting decisions during combat.

Here are a few interesting enemy combinations that I’ve found work well together:

- A blocker with a shooter positioned behind him. As the player tries to whittle down the blocker, the shooter is taking pot-shots at the player.

- A big chaser and a group of smaller flyers. While the player goes after the big guy, the little guys attack. However, if the player leaves the big guy alone and goes after the flyers, he’s gonna get thumped.

- A teleporter and a chaser. As the player tries to catch the teleporter, he leaves himself open to the chaser’s attacks.

- A guard and a bomber. While the player is tied up with the guard, the bomber attacks from above.

How Rapid is Rapid?

Depending on speed and movement, an enemy can be more dangerous, harder to target, and more frightening. Use the different speeds stationary, slow, medium, fast, and quick for your enemies.

The difference between a hazard and an enemy is mobility and AI, but every rule has its exceptions. Just because an enemy is non-mobile doesn’t mean he can’t move. Movement = character and life. A humongous Cthulhu-esque creature may be to too big to walk or fly around, but players would still consider him an enemy. Even an “inanimate object” like a turret can be smart enough to make life difficult for players. Design ways to keep players engaged as they attack non-mobile enemies, whether it’s a timing puzzle that stands between the enemy and the players, or even a puzzle that’s part of the enemy itself.

The speed, size, and strength7 of an enemy are inversely proportional: small enemies are fast but not strong, big enemies are strong but are not fast. Medium-sized enemies can be either strong or fast, but if you give them both attributes, they end up feeling “cheap” because they’ve been given an advantage that the player cannot match. Whenever an enemy is extremely overpowered or too perfect at making attacks, it feels as though the player is fighting artificial intelligence rather than an actual living creature.

But I digress.

Slow enemies work best when there are lots of them. One zombie isn’t very threatening, but a dozen of the slow-moving undead can make even the most stalwart hero a little nervous. Often, a slow enemy packs a big wallop: if players get hit, it’s their own darn fault. Or you can give a slow-moving enemy a fast attack to keep players on their toes. Slow enemies often have built-in defenses, allowing them to brace themselves against a player’s attack or casually swat him aside. If you want your enemies to feel powerful, have them move slowly like the Tyrant, Nemesis, and Dr. Salvador from the Resident Evil series. The inevitability of the bad guy advancing on the hero can make the player panic and make fatal mistakes.

Medium speed is just what it sounds like: the speed of the enemy’s movement and attacks will likely match the player’s own speed. Medium speed may be a little predictable, but it’s useful for most situations. I’ve found it’s helpful to make medium-speed enemies run slightly slower than the player character, especially when chasing him. This allows the player to retreat at running speed if necessary without fear of getting cut down from behind. The player can then reorient himself and face the enemy in time to deliver an attack or effectively defend. It’s OK to tweak speed values here and there to get the effect you want. There’s no hard and fast rule when it comes to this; you’ve just got to do what feels right and fair.

Fast enemies either dart forward to quickly strike and back away, or they move quickly around and then jump in to do multiple attacks. Fast enemies work great in horror and action games. Players will have less time to react to an incoming enemy and may panic and make dumb mistakes—until they learn to keep their cool. However, don’t make fast enemies constantly attack the players because they get frustrated by getting hit by something they can’t hit back—unless this is the strategy you want. The smaller the enemies, the quicker they are. Give fast-moving enemies an erratic movement pattern to give your players a real challenge.

Quick enemies move in bursts. They can move blindingly fast—so fast that it may seem unfair to players, but you can balance that by limiting their attacks and moves. Help players see quick moves coming by playing a warning animation. This will allow players to dodge, block, or strike before an enemy completes its quick move.

Movement Style

What is your enemy’s movement style? Does your enemy charge the player like an angry bull? Does he zigzag erratically to avoid taking fire? Does he make a beeline and then retreat? Does he jump from cover to cover? Does he crawl on the walls to ambush the player from above? Does he run away and never fight at all?8 Knowing your enemy’s movement styles will not only determine his attacks but also his personality.

Determine whether your enemy moves randomly or predictably. Avoid extremes and insert variety. Too random and the player might feel the enemy moves too arbitrarily. Too predictable and an enemy feels too “game-y.”

The best solution doesn’t include unpredictability. For Crash Bandicoot 2, Naughty Dog tried creating more behavioral AI with fewer simple patterns. Focus groups found them inferior. The players liked the challenge of figuring out the enemy’s patterns. On the flipside, players like unpredictability in sports games. Predictable patterns become “holes” for players to exploit, which ruins the realism of the experience.

Coordinating several enemies’ movements adds complexity. Consider how your enemies behave and group together during a fight. Some enemies can use flocking behavior to create realistic group movement.

Look at the movement behaviors of different animals, birds, and insects for inspiration. Humans usually move in straight lines. Predatory mammals like wolves and tigers move in looping arcs as they circle their prey. Crabs move sideways rather than straight ahead. Birds fly in swooping patterns as they catch updrafts to aid their flight. Insects zigzag as they course-correct during flight. Giving your enemies different movement patterns will make them feel more realistic.

Let’s consider how the bad guys in a Bruce Lee movie fight scene behave. Bruce Lee is surrounded by dozens of karate experts, but they never attack him in more than groups of ones and twos. They are very polite, those kung fu villains. This strategy works well in games too. It allows you to create the illusion of a group without overtaxing your game or the players.

Work with your programmer to create pathing AI. Determine the needs of your enemies to figure out how they are going to move around. Here are some questions that you should address when creating pathing and behavior AI:

- How mobile are your enemies? Do they have more than one movement speed? Can they can break into a run or slide to a stop? Do they leap over obstacles or use doors?

- How aggressive are your enemies? Fast-moving frothing berserkers or slowly advancing stone-cold killers? Enemies can even be cautious or cowardly, afraid to get hurt or die. Giving enemies a sense of self-preservation makes them feel like real people.

- How much like team players are your enemies? Do your enemies raise the alarm and alert other enemies to assist them? Will they try to keep a player pinned down while another closes in for a melee attack or better shot? Will they try to flush a player into the open where another enemy will have the advantage? Will one grab and grapple the player while another attacks? Do they have a “partner,” like a guard dog or attack drone?

- How defensive are your enemies? Do they crouch or duck behind objects? Do they use cover or hold the line? Do they act stealthily when they spot a player? Do they try to attack from behind and sneak up on a player? Do they have defensive items like shields or defense systems?

- How versatile are your enemies? Can they pick up and use dropped weapons or health? Do they drive vehicles or man weapon emplacements? Can they take over functions for other enemies if they are killed? Can they fly or use non-ground-based movement?

Most AI characters use a waypoint navigation system to move around. The designer lays out a grid or path that determines where the AI moves. As the AI moves, the programmer can determine what movement and animations are played to create specific AI behavior. Areas can be designated as “go” or “no-go” areas based on world geometry or to achieve a specific AI behavior.

All this means is that your bad guys either travel along a preplanned network of paths or wander around within the confines of an invisible box (or sphere).

Using such a system allows the designer to choreograph a world event with an enemy—like crashing through a wall or reaching a specific spot at a particular time. However, placing waypoints can be time-consuming, and they don’t always meet all the AI needs.

Because most waypoint-guided enemies are programmed to determine the shortest and quickest path to the player, be careful of enemies clipping corners and objects. You can fix this issue by tweaking your waypoint paths. Pull the waypoints in a bit at corners or near objects to compensate for this movement.

Bring on the Bad Guys

The player is walking through a graveyard winding his way through the tombstones when he sees a skeleton blocking his path, ready to fight.

Wait a second. Rewind. There’s a much more dramatic way to introduce this bad guy into your world.

The player is walking through a graveyard, winding his way through the tombstones. One of them shakes as he passes by. Suddenly, the camera zooms in on the player’s face as the screen shakes and the controller rumbles. The camera whip-pans around to a grave as a bony hand thrusts out of the ground! The tombstone shatters into a million shards as a skeleton warrior bursts from the grave, its eyes glowing evilly and bony fingers clenched, ready to fight!

Now that’s exciting!

Enemy introductions are a really effective way to tell players that they’ve encountered something new, exciting, and dangerous:

- Freeze the camera or zoom in on the creature: let players get a good look at what’s about to kick their butt!

- Display the name of the enemy on-screen. Players like to put a name to an enemy.

- Foreshadow what will happen. Resident Evil 2 provides a great “what the heck was that?” moment when a licker enemy runs past a window right before the player encounters him. Foreshadowing builds up suspense for the moment when the licker actually appears to the player. Make it an event!

- Introduce your enemies in a very dramatic way. Have them smash through a window, kick down a door, blast into the world in an explosion of special effects—anything to let your bad guys make a good first impression!

Keep in mind, not all games warrant an enemy introduction. Players of a multiplayer games wouldn’t want their own game play stopped while the introduction occurs. (Maybe they would if they could attack the player who is watching the introduction!)

Spawning enemies into the world is just as important as removing them. You want to make sure that players aren’t able to slaughter the enemies before they get a chance to arrive on the scene. Some games make enemies invulnerable upon spawning or have them spawn from off-screen where players can’t reach them. You may consider creating a hazard or mechanic that allows enemies to spawn on the playfield without getting killed.

In Maximo: Ghosts to Glory, we created coffins that burst through the ground to deliver enemies into the world. If the player collided with them, he would be knocked backwards. If he swung at them, he would shatter the coffin, but the enemy inside wouldn’t be hurt and would start attacking. We wanted to make sure the enemy survived entering the world long enough to fight the player.

Why go through all this trouble? Because of this very important thing:

FIGHTING ENEMIES IS SUPPOSED TO BE FUN!

Before I forget, here’s another very important thing:

ENEMIES SHOULD BE FOUGHT, NOT AVOIDED

I’m not talking about enemies that you have to dodge out before they hit you during a fight. No. I’m talking about the “this enemy is too hard, too cheap, too much of a hassle to fight so I don’t want to fight him” type of enemy. And yet, I always see the following type of enemy in a game:

This enemy has a bomb or some other explosive device. The enemy runs toward the player. If the player doesn’t get exploded, he will run away. Although this might sound exciting, in my experience this type of enemy always causes problems.

When the player runs, if the game is in third person, the camera tends to flip around to show the back of the player. In first person, the player can’t even see the enemy following him. In either case, the player can’t see the enemy at all. When the enemy explodes, it comes as a nasty surprise. Sure, you can give the player a warning with a HUD or in-game warning indicator, but in the end, you are going to design all kinds of stop-gap measures to help the player spot the enemy—but then that kind of defeats the purpose of the enemy, doesn’t it? Ultimately, this kind of explodey enemy just isn’t very good design.

In an action game, you are going to be fighting a lot of enemies, so do whatever you can to make the action awesome! Explosive effects, funny or dramatic hit reaction animations, cool and/or gory kills and, of course, lots of feedback and rewards.9 Why fight enemies?

- They have the loot. Gold, items, bolts, experience points, health—it doesn’t matter what it is as long as they have it and you want it.

- They block the path. You can block the player artificially to force a fight, like a battle arena.

- They have the key. And you need that key to get through the gate that leads to the next room, section, or level. I’ve always wondered: why is it the last enemy you fight is always the one who is holding the key?

- You need to take their power. Tired of getting shot at? Defeat those enemies and take their bigger, better guns! Want to upgrade your +1 mace to a +2? You’re going to have to fight that orc to get it!

- They’re making fun of you. Taunts are a great way to motivate players into fighting. Having enemies taunt or challenge players if they’re standing still for too long not only can force a player into attacking, but also is a great way to get some character into the enemies. Taunts work great in multiplayer fighting games like Street Fighter where the player takes a risk by taking a break from combat or defense to mock his opponent.

- It’s fun to fight. Nothing will keep a player fighting more than having a solid combat system. To achieve that, see Level 10.

Don’t forget to let enemies have a chance to be bad too! Give your enemies some sweet attacks like these:

- Melee attacks—Do they use hands/claws/tentacles/feet? Do they have raking attacks or punches? Do they know martial arts? Can they grab or ensnare? Can they perform throws? Can they “ground pound” or cause earthquake attacks?

- Weapon combat—Do they use weapons? One-handed or two-handed weapons? Are they barbaric or skilled fighters? Can they disarm or be disarmed by the players? Can their weapon be used by the players? Can the weapon extend, be thrown, or boomerang?

- Projectile combat—Do they use guns/magic spells/ranged weapons? How accurate are they with their attacks? Will they blindly fire or wait for the perfect shot? Do they track movement or lead when aiming? Do they need to reload? Is their projectile explosive? Can they be disarmed? Do they have a close-range melee attack if engaged or disarmed?

- Persistent damage—Does your enemies’ attack have a side effect like acid/poison/fire? Does it do damage with the attack or as a lingering effect? Can it be healed by the players, or does it wear off over time? Can it be countered by player equipment/gear?

Telegraphing attacks is important for effective enemy combat. An enemy should have a “tell” animation that informs observant players that the enemy is about to go all stabby, shooty, or clawey. Tells include

- Cocking a fist back to punch

- Growling or yelling before swinging a weapon or charging

- Moving part of the anatomy (like a twitching tail or reptilian fins) before attacking

- The weapon’s laser sight acquiring a target before firing

- A weapon or spell “charging up” before firing

Not every attack needs to do damage to the player. There are plenty of ways to give the player grief without doing permanent harm:

- Block/parry—The enemy can block or parry the player’s attack, causing a stagger in the player’s combat flow. This can break combat chains, reset combo meters, and cause the player’s weapon to rebound or ricochet. Whatever the source of the block, be it a force field, an actual shield, or a defensive grab, don’t ever make the player wonder why it happened.

- Knock back—Rather than taking damage, the player is knocked backward when hit. Putting distance between the enemy and player can upset any combat chain or disrupt any activity the player was engaged in, like spell casting or operating a mechanic. It is particularly effective when the player is hit while standing on a narrow platform, knocking him off or to his death.

- Stun—The player is stunned into a defenseless state. The player should lose momentary control—just as long as it doesn’t last too long, which can be very frustrating for the player. Circling stars and tweeting birds effects are optional.

- Freeze/paralyze/capture—This type of attack acts like a stun, but the player can break out of it by button mashing or furiously waggling the control stick. Characters are often entombed with a freeze attack, snared by a spider’s web, or caught in some sort of netting. The player may or may not take damage during this attack. Make sure you have a cool “victorious breaking free” animation and effect when the player finally regains control.

- Repair/heal—The enemy regains health. I suggest using this behavior infrequently because it can feel unfair to the player. It works best if the enemy has a healing animation as well as a health bar to show that he’s returned to his fully (or partially) healed state. Consider allowing the player to attack the enemy to disrupt his heal.

- Buff—This effect works like the heal, but the enemy gains power to charge an attack. Usually, this effect can be found when charging magical attacks. You also find it in shooters when the bad guy is charging up his weapon to unleash his wrath on the player. The enemy can be in either an invulnerable state while buffing up or the reverse, which would cause the enemy to lose the advantage he sought.

- Steal—The enemy steals money or equipment from the player, causing the gameplay dynamic to shift from “fight the enemy” to “get that creep who just stole my chainmail!” Make sure the player has a fair opportunity to get back what’s been stolen. Never steal anything the player has bought or won as part of progression; make it something that is (somewhat) easily replaceable.

- Leech—The enemy drains the player’s “charged up” resources. This can be super meter power, mana, shield power, or even fuel. Usually, the player doesn’t have an opportunity to regain the resource from the enemy that attacked it. Once it’s gone, it’s gone. Players will soon pick up that leeching enemies should be dispatched as soon as possible.

- Perform unexpected behaviors—If the player is expecting a movement pattern or attack, having another up his sleeve adds a nice bit of variety to the encounter. The variety adds to the illusion that the enemy is learning to react and defend against the player. The player will have to adjust his battle plan as he goes rather than falling into the same old routine.

- Show vulnerabilities or resistances—Make sure they’re clear to the player and follow logic. Of course, that murderous snow angel is going to be vulnerable to fire, just like that flaming pyre corpse is just going to laugh in your face when you wave that burning torch in front of him. Let the player make logical connections; don’t ever let him wonder why something doesn’t work. Enemy taunts are great for conveying that information. The more smug or cutting the enemy’s taunt, the better. Just don’t overdo it; even the funniest or best-delivered line gets boring after the third time.

Even if an enemy has fierce attacks, nimble defenses, and cool behaviors, there still has to be a way to kill him. You determine an enemy’s health the same way you would for player characters. Balance your enemy’s health in relationship to the player’s attack. Start with how many hits you want your enemy to take before he dies. Consider all the different attacks your hero has when determining this. Your goblin enemy may be able to withstand three normal hits, but a flaming sword may be able to kill him in one stroke.

All the notes about displaying player health apply to the enemy’s health as well. Refer to Level 10 rather than make me retype it all here.

I Love Designing Enemies

Enemies offer you a chance to really flex your creative muscle as a designer. It’s fun to come up with horrible monsters and evil villains. Personally, I find adversaries to be the most interesting characters in a story. And not just the “big bad” bosses. Look at all the great cannon fodder found in movies and comics: Imperial stormtroopers, orcs, Cobra troopers, death eaters, AIM scientists, parademons, Nazi soldiers, those henchmen in James Bond films that flip through the air whenever a grenade explodes.

But I’m proud to report that no one comes up with more creative cannon fodder than video game designers. In games, anything can be an enemy! An angry pickle! An irate toaster! Whatever the heck a goomba is! A whole glorious world of psychopathic possibilities is yours for the choosing … but rather than overwhelm you with a huge list,10 I’ve created—tada!—

The Alphabetical Bestiary of Choices

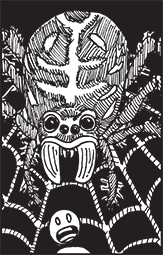

A is for arachnid, our pois’nous, crawly friend. Beware his webby legs or you’ll meet a sticky end.

Battlemechs, huge and metal, with cannons all a-blazin’. Stand beneath their feet, and you’ll go squish just like a raisin.

C is for criminals, quite the cowardly lot. Better catch them quickly, or you’re likely to be shot.

D is for the dinosaur that’s chewing on my rear. Who said genetic engineering was such a good idea?

Evil creepy children, blank eyes stare so sadly. They’re easy to dispose of (’cept when guarded by Big Daddy).

Flying devils bedevil you while climbing a wall. Give ‘em a whack, knock ‘em back, before they make you fall.

I hate those Ghosts who chase me merely out of habit. But they’ll run the other way if I eat a power pellet.

Henchmen, mercs, and soldiers: they’ll kill you for a buck. My advice? Shoot them first. If they shoot back, duck.

Irradiated Insects! It’s my house they invade. Someone know where I can find a 10-foot can of Raid?

Do not shoot a Jungle Beast; treat with kindness instead. Even when it steals your gal, throwing barrels at your head.

Killer Plants may look pretty, but do not stop to smell. Shooting thorns and whipping weeds will send you straight to hell.

A Lich is just a skel’ton that has a fancy name. You should place a score or more of these into your game.

M is for mutant freaks, scarred by radiation. Their drippy flesh could use a little bit of lotion.

Red Ninjas vanish from sight, throwing stars at you. If they do any other attacks, make sure to tint them blue.

Orcs, the standard foe of any knight or wizard. Can be fought by the score in any game by Blizzard.

P is for the pirates who sail the seven seas, in ships laden with treasure and crews full of disease.

Dragon, spider, alien: whichever type of fiend; they’re always harder to defeat when they are called “the Queen.”

Robots are a paradox—they’re s’posed to make life better. But when they’re in video games, they always make me deader.

Spaceships, as an enemy, come in many flavors. Try Galaxian, Sinistar, or plain ol’ Space Invaders.

T is for treasure chest; their mimics should be banned. First you’re reaching for the gold, but then you lose your hand.

Darn those Unholy cultists! Their demons are a blight. They’re crazy, but without these guys, there’d be no one to fight.

Vampire bats are all a-twitter, flying rather quickly. Trying to draw a bead on them is making me feel sickly.

Werewolves have fearsome claws, sharp and ready to maul. But rendering all that hair makes games slow to a crawl.

Xenomorphs are nothing but an intergalactic pest! They eat your brains, infest your ship, and burst right through your chest.

Behold these enemies of Yore! Gorgons and animal-men. (Lead designer’s been watching Harryhausen films again.)

Zombies are the final foe, so with your gun, take aim. They’d be so much scarier if not in every game.

If you don’t want to use any of those traditional enemies, don’t sweat it. Come up with your own foes! Here’s how:

- Start with your theme. Brainstorm the types of enemies based on your game’s environment. For example, an ice world can have killer snowmen, yetis, disgruntled skaters, snowball-throwing wizards, and penguins with machine guns.

- … or start with your story. Who is the main enemy in your story? For example, in an original trilogy Star Wars game, I would expect to be fighting stormtroopers no matter what planet I am on. Other villains can appear, but players should be constantly reminded of their arch-nemesis.

- Come up with a way to tie the two of them together. What’s the one visual or behavioral cue that will differentiate your enemy from the others in your game? Or from other games? Within your game, you can create groups of enemies based on shapes, color, physical attributes, weapons, or uniforms.

- Be economical with your enemies. Re-use models, animations, and textures wherever possible to get the most bang for your production buck. When creating similar enemies with different behaviors and attacks, make them look different at a glance. I call this design mentality “Red Ninja/Blue Ninja” because a red ninja enemy may be set to hop and throw shuriken, whereas a blue ninja may use dash attacks with sai. Sub-Zero and Scorpion, two of the most famous characters from the Mortal Kombat series, were originally just reskinned versions of each other.11

- Decide whether the enemy belongs in your world. You wouldn’t expect to find a cybernetic death-mecha in a Super Mario game; that world is too whimsical for such “serious” enemies. Conversely, a goomba would be seriously out of place in a realistic Medal of Honor style title.

- Make your enemy look like an enemy. Glowing red eyes, demonic horns, fangs, clawed hands, spikes, skull ornamentation, ragged capes, fearsome masks and helmets that obscure faces. Sure, this is stereotypical imagery, but if your players see characters in the world with any of these visual traits, they’re going to shoot first and ask questions later. Stereotypes are stereotypes for a reason: they’re easy for viewers to understand. Don’t be afraid to use them to your advantage.

- … or go against expectation and type. You can go against type and juxtapose your enemies’ visual with their behavior. How about a cute bunny that turns into a slavering killer? Or a hulking troll that will burst into tears when attacked? The more personality you can add to make your enemies feel and look unique, the better.12

I Hate You to Pieces

When introducing your boss to players, do it in a memorable fashion. Who can forget Darth Vader’s entrance in Star Wars? Make sure players get a good look at the villain, that they understand “this is the bad guy” they will eventually fight. You always want to give your main villain13 a “Joker moment,” when the bad guy executes a henchman or some other NPC to show what a truly bad guy (or girl or he-she-demon) he is. This can happen within the game or a cutscene.

Have other characters talk about how bad the boss is before you introduce him. Or give the players information in collectable form like audio clips or data files or letters to warn them about the enemy. This works when dropping hints to players on how to defeat the enemy or boss. Arm them with knowledge along with the firepower. Anticipation of fighting the boss will be greater if players know the fight is coming.

When I was working on a game based on the movie Demolition Man, the designers were presented with an interesting challenge. Simon, the movie’s bad guy, didn’t fight the hero until the very end of the game. But the designers knew that Simon had to be a recurring villain in the game, so they came up with a clever solution.

At the start of every level, Simon would run out onto the screen, shake his fist at players, and then run off. The effect on players was electric. They’d shake their fists back and say, “Oooh! That darn Simon! I’m a-gonna git him!” and then proceed to blast their way through a half hour of gameplay. By the time these players reached the next level, they were probably so heady from all the killin’, they forgot why they were there until Simon would run out again, shake his fist, and re-energize the players. This taught me a very important thing:

MAKE THE PLAYERS HATE THEIR ENEMY

How? Simple. Make sure your boss does bad things! This is why villains are always killing off their own henchmen—so that they have someone to kill if they can’t kill the main characters! Have the enemy take something the player needs or cares about. Kill the hero’s parents, kidnap the princess girlfriend, burn down the quaint village—you get the idea. Whatever your enemy does, make sure it impacts the gameplay as well as the story. Make the parent the blacksmith that gives the hero that magic sword. Does the girlfriend heal the hero whenever he visits her hut? Not anymore! The enemy just kidnapped her! And now that the village has burned to the ground, where is the player going to store all the collectables he’s found? Japanese RPGs do this right: they kill off the player’s girlfriend, who happens to be your best party member. Are those tears I see? Are they being shed for a lost love or because you can no longer heal every other turn?

When it comes time to design your boss fights, you don’t have to kill the boss at the end of each battle. In fact, it’s better if you don’t. This way, you give the player someone to fight later in the game. Because your player will have “history” with this bad guy, he will hate him even more! If you kill off your enemy in the first act, who is left for the player to fight? Unmotivated, your hero loses the will to live, starts drinking, and moves in with his parents.14

Pathetic.

And more importantly, not fun.

Taunts are a great way to get the player mad at an enemy, but you have to be careful not to overuse them. To paraphrase Spider-Man, “With great power comes dialogue-the-player-is-going-to-tire-of-hearing-over-and-over-again.” Taunt the player physically as well as verbally. You can even build these taunts into your enemy’s attack moves. For example, in Maximo: Ghosts to Glory, there is a sword-wielding skeleton that, every time he successfully hits the player, does a little flourish with his sword, like a gunslinger spinning his guns before he holsters them. This flourish was created to give the player an opportunity to strike back and wipe the grin off that cocky little so-and-so’s face.

Simple animations like idles and taunts go a long way toward making an enemy feel smarter than he actually is and provide lots of character. Has the player retreated too far for the enemy to attack? Have the enemy berate the player or make “come here” gestures. Did the player successfully elude the enemy with stealth? The player should shrug his shoulders and mutter that he must have been seeing things. Some games have guard enemies taking smoking breaks or falling asleep at their post to make them easier pickings for the hero. But keep in mind you don’t want every one of your enemies to act this way; otherwise, you’ve just thwarted the uniqueness you were trying to achieve.

One last thing about enemies: sometimes you should let the bad guys win.

I don’t mean killing off players to give your enemies a victory, but you shouldn’t baby your players either.15 Let the enemy get in a hit (or a cheap shot) once in a while. Give the enemy a temporary invulnerable attack state. Force the player to run away or at least block an attack. Have your enemies outnumber the player several times over. Let them sweat it out as to whether they’ll survive the encounter. The player should feel as though he is actually in danger from the enemies. Bad guys aren’t going to feel very threatening if the player doesn’t have to struggle to defeat them. And the players’ victory is going to feel hollow if the enemies don’t provide a challenge.

Non-Enemy Enemies

As mentioned at the start of this chapter, not every game has physical enemies that are to be overcome with hot lead and cold steel. There are plenty of ways to push and punish your players without resorting to fighting sentient beings:

- Gremlin—This character looks like an enemy but doesn’t directly engage the player. Instead, a gremlin will disrupt the game by undoing the player’s progress. For example, SimCity features a Godzilla-like monster that stomps through the player’s city, leaving destruction in his wake.

- Tormentor—This enemy challenges and taunts the player throughout the course of the game but never directly confronts or attacks him. The alien overlord of Space Fury and Portal’s sentient computer GLaDOS are examples of tormentor enemies. In the case of Portal, the player can “defeat” GLaDOS by tearing her apart, but it is implied that—SPOILER ALERT!—she is “still alive” at the end of the game.

- Time—“Time pressure makes people think something is a lot more complicated than it really is.”16

- Human competitor—Player versus player, competitive or cooperative—regardless of the gameplay mode, I find the best and worst thing about multiplayer games is … the other players.17

How to Create the World’s Greatest Boss Battle

Video game BOSS (n): a large and/or challenging enemy that blocks a player’s progression and acts as the climax/ending to the game’s environment, level, or world.

At first glance, a boss battle may appear to be an encounter with a very, very, very large enemy with too much health. But this is an underestimation. Bosses are very complex creatures with many separate working parts that should be thoughtfully designed.

Just as with enemies, boss characters are fun to create. But before you start designing your boss, you must first make sure that you have completely defined the player’s move-and-attack set. When that’s set, you can design a boss fight in three different ways:

- Learned moves—The boss encounter is designed around the players’ existing set of moves. You don’t have to teach the players anything new, and they feel as though they’ve mastered those skills when they defeat the boss. The Mario titles design their bosses this way.

- New abilities—The boss encounter is designed around players gaining a new weapon or new move. The players’ learning curve is part of the boss round’s difficulty. You find this in many of the bosses in the Legend of Zelda series.

- Combination—You can try to use both methods in one boss fight, but why complicate things for players? Don’t be so mean.

Who’s the Boss?

Boss design is just like enemy design: form should follow function. Knowing the boss’s movement and attacks will determine the boss’s appearance: if he can shoot, give your boss a gun (or a magic spell or a rocket launcher or a large nose to sneeze out nose goblins); and if he can defend himself, give him a shield (or a force field or protective cowling or a missile-deflecting karate move). In a nutshell, if the boss can use it, he should have it.

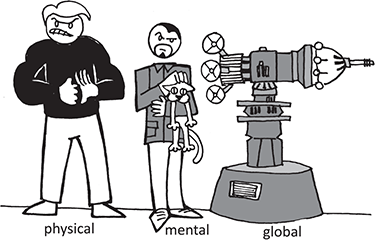

Next, consider how the boss relates to the hero. No, I don’t mean in a “Darth Vader is your father” way, but rather what the boss represents. The James Bond movies of the 1960s and 1970s had a really good formula for bad guys. There were technically three “boss types” that Bond had to defeat.

The first villain was the arch henchman: the physical adversary. A muscle-bound goon would beat the tar out of Bond until he turned the tables with one of his spy gadgets or a deftly executed judo move to throw the goon into a pool of piranhas. Physical adversaries in the Bond films are the classic henchmen like Jaws, Tee Hee, and OddJob. In video games, these characters are monstrously large, freakishly hideous, and very heavily armed.

The second villain type is the mastermind: the mental adversary. Bond fought these villains at the film’s climax. Usually, mastermind intelligence leaves the hero at a disadvantage and against overwhelming odds. In video games, this is when the boss gets into his robotic suit to blast away at the hero or forces the player to solve an environmental puzzle that, when solved, brings the cackling villain to his knees.

Even though the mastermind has been defeated, there is still one more “villain” to defeat: the global threat. This isn’t a person so much as a threat to the hero’s world. This can be the timer on Goldfinger’s nuclear bomb, Hugo Drax’s deadly spore bombs, or SPECTRE’s space-capsule-eating rocket.

Here are some questions to consider when designing bosses:

- What makes the boss a worthy adversary? Most bosses have the upper hand on players in size, strength, firepower, and defenses. Make sure players know they are in trouble even before the fight begins.

- What does the boss represent to the hero? In many games and movies, the villain is merely an obstacle to the hero gaining true love (rescuing the princess) or a threat to peace. But don’t be content with those tropes. Villains can represent the inner demons of the hero. In Return of the Jedi, Luke Skywalker must reject the dark side and become like his father in order to defeat the Emperor (or at least motivate daddy to toss him down a shaft).

- What does the hero gain by defeating the villain? It shouldn’t be treasure, weapons, or power. In most movies and games, the hero is content to merely save the world and restore the status quo. But in the classic “Hero’s Journey” story structure, the hero returns from his adventure with knowledge. For example, in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, Indy finds out that fortune and glory aren’t the only important things in life.

- What is the boss’s motivation and goal? Give your boss a more compelling motivation than “he’s evil.” I find “the seven deadly sins of man” (lust, gluttony, greed, sloth, wrath, envy, and pride) to be a great starting point for villainous motivations. The Riddler wants to prove that he’s smarter than everyone. Voldemort wanted to regain his corporeal form and power. Sinistar is just hungry. Whatever the villain’s motivations and goals, they have to come in conflict with the hero’s own. The boss is the primary obstacle to the hero’s success. Only after the villain is defeated can the hero truly achieve his goal.

- What’s the boss’s job? In video games, most bosses are guardians: the guardian of a magic weapon, of a captured princess, of progression. But by keeping it at just this, you are doing a disservice to your villain. Give your boss a motivation for doing what he does.

- Is your game based on a licensed property? Remember that these boss fights are the highlight of the fans’ play experience. If you aren’t a fan of the property yourself, research it enough to find out what the players would want to do. It’s safe to say that Star Wars fans will find a lightsaber fight against Darth Vader a lot more thrilling than shooting down his advanced TIE fighter.

Congratulations! You’ve done a great job giving your boss a believable motivation, clear goals, and an intriguing backstory. He looks menacing and has awesome attacks and behaviors. But the most common way to make a boss look bad and dangerous is to make him huge.

Size Matters

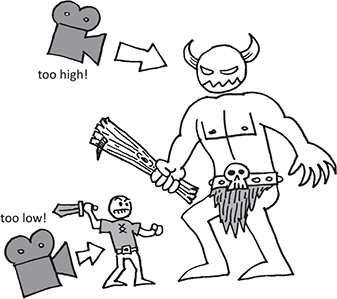

A bigger boss means a badder boss … and bigger camera problems. You can start to solve this issue by always focusing the camera on the boss. Because the boss should completely command the player’s attention, you should try to keep the boss within camera view (unless the player does something stupid like turn his back on the boss). Avoid placing your camera:

- Too high—The high angle de-emphasizes drama and the scale of the boss.

- Too low—The foreshortening that happens makes it hard to gauge the distance to the boss and see incoming attacks. It can also cause clipping issues if the camera drops through level geometry.

Use elevation in the level and with the boss to help rectify some of this issue. Allow the player to reach the boss by climbing geometry to higher elevations. Or you can bring the boss down to the player’s level just in time for the player to give the enemy a good smack to the face. One thing you want to avoid is crotch whacking. This is when the player is just tall enough to reach the crotch of the huge boss.

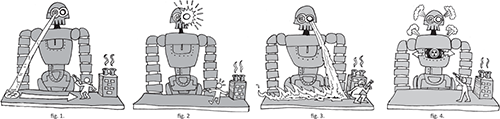

A big boss means big attacks. Why be content with the boss throwing rocks when you can have him throw cars? Why not buildings? Or entire city blocks? The more dramatic your attacks, the more memorable they are. Take inspiration from games with bombastic bosses like Contra and God of War 3. Regardless of how spectacular the attacks are, you will need to give the player an opportunity to fight back. The player needs to work out when it is safe to attack. The player needs to memorize the boss attack patterns. Patterns are at the heart of every traditional boss fight and are created when several attacks and behaviors are strung together into a predictable sequence. Here’s a simple example to show how patterns can be created:

Let’s say the player is fighting a giant mech armed with a laser cannon. The cannon’s laser sight sweeps the arena three times (fig. 1). Once the sight has acquired a target (the player), the cannon will fire a stream of laser blasts—first to the right, then to the left, and then in the middle of the arena. The mech’s cannon then transforms into a larger weapon. This new form charges up for a second (fig. 2) and then fires a single thick beam that sweeps the ground of the arena and can be avoided only by jumping or ducking behind cover (fig. 3). When the attack is over, the mech’s chest cowling pops open and vents steam (fig. 4). After a couple of seconds, the cowling snaps back closed in a burst of electricity, and the mech retransforms its cannon back into its original configuration. The attacks cycle until there is a break in the pattern initiated by the player, such as the player taking damage, dying, or successfully attacking the boss.

This example shows the components of a boss fight: the primary attack, the invulnerable attack, the vulnerable state, and opportunities.

The primary attack, the laser blasts, create movement patterns for the player to memorize and follow (left, right, center). As long as the player knows that sequence, he’ll be able to avoid taking damage.

Movement patterns should be easy to remember, but you should feel free to change the order of events to add some variety. Random movement patterns can be used, but I have found that many players find them difficult to determine and get frustrated if they don’t “luck” into a favorable pattern.

The invulnerable attack, the charged cannon shot, is a dramatic, large-scale attack that forces the player to take avoiding action. As the player cannot hurt the boss during this attack, the player must act defensively, breaking up the play pattern.

The vulnerable state, the mech’s chest cowling opening up, reveals the boss’s weak spot to the player and is vulnerable to the player’s attacks. This should be the chance the player has to inflict the most damage on the boss. The boss’s weak spot should be visually designed to be obvious to the player: make it flash or glow, or highlight it in some manner. It should stick out like a sore thumb. You can prolong a vulnerable state by stunning or incapacitating the boss. It becomes very clear to the player that he has a chance to attack without the fear of being attacked in return. Make sure you end the vulnerable state with an attack/event of some sort (in this case the electric burst), which pushes the player away from the boss and informs the player that his chance to attack the boss is over.

Opportunities, like the cannon changing form, are chances the player has to attack. The window of opportunity is usually shorter than the one given by the vulnerable state. Taunts work well for this too. Just don’t overuse any vocal cues or the player will get tired of hearing them over and over again.

I like to think of boss battles as a dance between the enemy and the player. Alternate between offensive and defensive moves for both the boss and player. Get more mileage out of your boss attacks and moves by changing the timing, speed, and range; just make sure these changes escalate. Most bosses start out pretty easy and get harder as they go. This is why many bosses have several rounds of patterns: the boss gets madder, and the threats ramp up until the ultimate climax when the boss is defeated.

Even as your boss is trying to kill the player, make sure to do all you can to keep the fight going. Provide plenty of opportunities for the player to regain health or power during the fight. Tools like dynamic difficulty will programmatically determine what the player needs to succeed. You can apply dynamic difficulty to enemy AI, reaction times—in fact, just about anything. Delivering the right power-up exactly when the player needs it makes the boss fight feel exciting and dramatic.

I also think the last boss battle of the game should be the easiest. Why? Because I want the player to end the game on a high note and feel like a triumphant hero. He’s already done the hard part—playing through the entire game.

When the player gives the boss his comeuppance, use animations, sound cues, and visual effects to show that the player is damaging him. A robotic enemy can shoot off sparks; a fleshy foe can spray out spurts of blood or ichor. Other bosses will limp or crawl as they are close to death. Work with your artist to build your boss to have parts get chopped off or use several models that show increasingly damaged states. No matter how your boss goes, remember this very important thing:

LET THE PLAYER ADMINISTER THE COUP DE GRÂCE

The last strike of the fight needs to be delivered by the player. It’s very important psychologically for the player to feel that he has won. This is the climax of the encounter. Don’t rob your player of his victory with a cutscene or a canned animation. Once the boss is dead, let the player savor the moment with celebratory text, music, or effects.

Sometimes, due to story or licensing needs, your enemy will escape at the end of a boss fight. As the enemy escapes, do it with style. Having an enemy escape to fight another day shows the player that he is a worthy adversary and another encounter is coming. But even if the boss escapes, you still need to make the end of the fight satisfying. You need the false kill. You must first knock the boss to his knees before he gets up and runs away. Hold camera on that defeated boss for a moment. Let him curse the player’s good luck (because it’s never skill that defeats a bad guy, right?). Make sure it’s clear to the player that he’s won the fight.

When the enemy is defeated or killed, what happens to the enemy? Does he vanish in a puff of smoke or pop like soap bubbles? Does he dramatically clutch his heart and die an agonizing death? Does he explode? How is treasure delivered to the player after the enemy is defeated?18

Determine how the enemy model is removed from the world. Does he fade away, leaving only weapon pickups where his body once was? Does he dissolve into a pile of goo that then melts away? Or does the body stay on-screen as a gory reminder of your combat? Remember, what happens to your enemy affects your ESRB rating.

One more thing: sometimes a player is going to die. When he does, make sure he returns to a safe respawn point. The boss shouldn’t attack until the player is ready to fight. Consider keeping the boss’s game state upon the player respawn. This means picking up the fight where the player left it rather than restarting the entire boss fight sequence from the beginning.

Location, Location, Location

Where a boss fight takes place is just as important as the design of the fight itself. The level is an extension of the boss fight … and sometimes, the level IS the boss fight.

The basic boss fight takes place either in a circular arena or a linear screen-wide walkway. This allows the camera to stay focused on the boss, who generally inhabits the center or back of the room with occasional trips to the side and outer edges. For more dynamic boss fights, add elevation to the arena. Devil May Cry had an interesting fight in which the player kept alternating between fighting the boss high up on the walls of a castle and down low in the castle’s courtyard.

Think about the boss in relationship to the environment. How will a boss use the level for movement or attacks? Having dynamic elements like collapsing statues or walls or break-away floors can keep things exciting and surprising as the environment gets wrecked by the boss (and the player) over the course of the battle. Bust that joint up! Just be aware that if the player has to replay the boss fight, seeing the event happen again and again may get a little stale.

Designing boss arenas with dynamic level elements is the best of both worlds. The arena contains dynamic objects and elements that will react to a certain boss attack or action. These can be breakable windows, smashable floorboards, crushable computer consoles, and so on. This way, no matter what order the boss interacts with these elements during the battle, interesting things will happen. It creates a different experience every time.

A scrolling battle, where the player and boss fight their way through several locations, makes for a dynamic boss fight. First determine the method of player locomotion during the fight. Are the player and boss fighting on foot (chasing each other?), on top of vehicles (like the moving train in Uncharted 2: Among Thieves or hopping from car to car as in Wet), or while piloting vehicles? (Maybe they are vehicles!) Just be careful because scrolling boss fights require as much work if not more than a full level.

Another variation is the puzzle boss: a boss that is actually invulnerable and cannot be defeated by a direct assault by the player. Instead of fighting, the player has to survive the boss’s attacks long enough to use objects in the level that will defeat it. Spidey can’t actually hurt the Rhino boss in Spider-Man 2 (Activision, 2004), but if Spidey can trick the Rhino into smashing into electrified machinery, he can defeat him. The most obvious (and hilarious) example of a puzzle boss is in You Have To Burn The Rope (http://www.youhavetoburntherope.net) where the Grinning Colossus can only be defeated by … well, I’ll let you guess how to beat this one.19

Why Not to Create the World’s Greatest Boss Battle

Some designers believe that boss fights are too “old school”—that they grind game progression to a halt; that the time and effort to create bosses with their non-reusable artwork, hard-coded behaviors, and unique animations just isn’t worth the production cost. Boss fights create a skill gateway; whenever someone has told me that he quit playing a game, the reason was usually that a boss was too hard.

An alternative to these problems can be found in turning the boss fight on its head. Instead of making it about a big creature, make it about big drama. Make the fight personal to the player and more about pivotal moments in the story.

My friend, designer Paul Guirao (Dead to Rights, Afro Samurai), created what I thought was the best boss fight design I had ever heard. Early in the game, the player learns an arm-wrestling mechanic. At the climax of the game, the hero is knocked to the ground by the villain, who attempts to plunge a dagger into the hero’s eye! The player has to use that arm-wrestling mechanic to force the dagger away and eventually turn it on the villain himself.

Paul’s design really opened my eyes (groan) to what a boss fight could be. It sounded awesome and dramatic and very different from anything else I had seen in games. It wasn’t just another big stompy boss. What I really liked about it was that it

- Emphasized drama over scale—It didn’t need a rocket-firing colossus rampaging through a city to be exciting.

- Used intimacy to create urgency—Because the camera view was to be very tight (only the faces of the two characters, their hands, and the dagger were to be shown), the impending danger was heightened to a degree not seen in most video games.

- Better utilized existing assets—All the assets for the fight—the hero, the villain, the dagger, the arm-wrestling HUD meter—were used in other parts of the game. Nothing new had to be created to make this boss fight playable.

- Told the story with a boss fight, not cutscenes—Video games are interactive entertainment, so playing the story is always better than watching it.

SPOILER ALERT!

Years later, as I played the ending of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2, I was reminded of Paul’s knife-fight design. In CoD:MW2, the player character is stabbed by the game’s villain. As the bad guy attempts to murder your partner, the player has to (painfully) pull the knife from his own chest and hurl it into the bad guy’s eye (all occurring in very dramatic slow-motion).

Had the designers at Infinity Ward heard of Paul’s knife-fight design idea? Or was it just a good idea for a boss fight whose time had finally come? All I know is that it was as awesome and dramatic as Paul’s boss fight idea had sounded to me all those years ago.