Level 16

Some Notes on Music1

WHEN THE IMAGINEERS were creating the Star Wars Star Tours attraction at Disneyland, they initially intended the experience to be “realistic.” The audience would hear only the sound of the Starspeeder 3000 and the pilot’s dialogue. However, when they tested the attraction, something didn’t feel right. Without the classic theme by John Williams, the attraction just didn’t seem like “Star Wars,” so the music was added in.

Music brings a lot to any entertainment experience, be it a theme park attraction, movie, or video game. But it also requires a lot of work and coordination between many members of a team, which contributes to the reason music and sound are usually left until late in production. This is a mistake. Sound and music can bring so much to a game that leaving it until to the last minute means missing out on some great design opportunities.

Music and sound in gaming have come a long way in a short time. Back in the 1970s and 1980s, arcade and console programmers had only electronic beeps and boops to play with. Even with those limitations, game creators were able to create some simple but memorable musical themes (or even just jingles) for games like Pac-Man, Donkey Kong, and The Legend of Zelda. Sound advances happened with almost every system; voice synthesizing and MIDI format audio meant that music became more lush. However, game creators were limited because sound and music files took up a good amount of memory on cartridges.

The big jump in game music came with CD media games. Starting with Red Book audio (Red Book being the set of standards for CD audio), music in games began to sound just like any other recorded music, and it was possible to store more of it on the CD. As games moved onto DVD media, the biggest problem with sound and music—storage space—was no longer an insurmountable issue. Nowadays modern PC and console games use streaming sound (compressed into MP3s, Ogg Vorbis, or console-specific formats and decompressed as needed by the sound chip). Emphasis shifted from the programmatic issues with music and sound to what to do with it creatively.

The first question you need to ask yourself when thinking about music design is, “What kind of music do I want?” There are really two answers to this question: licensed or original.

Licensed music is previously recorded music that can be “licensed” for use in a game for a fee. While music publishers own the rights to the recorded music, companies that work on behalf of the publishers, including the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) and Third Element, negotiate licensing deals. Game publishers usually handle the job of obtaining the rights to music licenses and negotiating deals.

Because video games currently don’t generate royalties once published, game publishers will negotiate one-time buy-out fees for music licenses lasting over a period of seven years to “life of product.” Licensing fees can range from $2,500 to more than $30,000 a song. The more popular and prestigious a song is, the higher the licensing fee. I don’t want to think how much the licensing fees were for The Beatles: Rock Band (EA, 2009).

If the song you want for your game is too expensive for your budget, don’t fret; there are still plenty of options. You can license a less-expensive cover version of a song—this was done in the first Guitar Hero (Activision, 2005). Or you can find a similar sounding but less expensive song at a music library. In fact, libraries are great if your game calls for a wide variety of musical styles or requires incidental music, like that heard on a radio or in the background of a bar scene.

Your other option is to use original music. Original music is a composition that is created specifically for your game. Unless you can compose, perform, and record your own music, I suggest hiring a music director to work with your team.2 Not only will she create the music, but she can also handle the resources required for performing, recording, and preparing the music for your game. Even though that’s a lot of work, a game designer still has plenty of prep work to do before even getting to that stage.

I Know It When I Hear It

I find it helps to be able to talk to a music director in his own language, even if you can’t write music, play an instrument, or carry a tune. You just have to know what you like and have an opinion about it! Provide examples of what you want for your composer: try to cut out as much of the guesswork as possible. For Maximo: Ghosts to Glory, I gave the composer a mix tape of music from movie soundtracks and songs I thought would be appropriate for the game’s levels. While they say that “a little knowledge is a dangerous thing,” I have found it useful to develop a musical vocabulary so you are speaking the composer’s language. Doing this will make it that much easier to request changes when you know what to listen for and what it’s called.

Here are a few musical terms that I have found useful to know:

- Accent—Emphasis placed on a beat to make it louder or longer. As in “please place more accent on the drums.”

- Beat—The “pulse” of the music. Music is measured in beats. Music can have fast beats or slow beats.

- Chord—Three or more tones played at the same time to create a harmony.

- Instrument—An object that produces music. Synthesized music replicates the sounds instruments make. The choice of instrument can greatly change the theme and mood of a piece.

- Mood—The “feel” or theme of a musical piece. The mood of a musical piece can be based on emotion (fear, excitement), action (sneaky, combat), or even location (tropical, Russian). Mood is created by instruments and changes in tempo and beat.

- Octave—This is the interval between one musical pitch and another with half or double its frequency. One octave up has twice the pitch; one octave down has half the pitch. You will likely be telling the composer to bring something “up an octave” or “down an octave” to make it sound higher or lower pitched.

- Pitch—The highness or lowness of a tone. A tone’s pitch can be adjusted either higher (to sound like the Chipmunks) or lower (to sound demonic). A tone’s frequency is adjusted to add variety into game sounds without creating new sounds. For example, a sword clanging on metal can have its frequency changed so the player doesn’t have to hear the same sound over and over.

- Rhythm—The controlled movement of music in time. Ravel’s Bolero builds in rhythm to a frantic conclusion.

- Tempo—The rate of speed of the music, which can range from very very slow to very very very fast. There’s even a specific tempo for walking speed called andante!

- Theme—The “heart” of the musical composition. Usually, a composer will come up with the theme first and then “flesh it out” to fit the length required. For example, John Williams created the Raiders of the Lost Ark March when Steven Spielberg couldn’t decide between which of two themes he liked better … so he had Williams combine them!

- Tone—The sound or characteristic of a particular voice or instrument.

- Upbeat—The last beat of a measure, but can also refer to making the music sound happier, friendlier, or faster.

- Volume—The softness or loudness of the music.

Music with Style

Now that you can communicate with your music director, you need to consider the genre of your game. What style of music do you want for your game? A traditional route would be to use the style of music generally associated with that genre. Say you’re making a sci-fi game. Do you want orchestral music like John William’s score from Star Wars or something like Vangelis’s synthesized music from Blade Runner, or do you want to go old school with 1950s’ theremin3 music in the style of the original The Day the Earth Stood Still? Feel free to go in another creative direction: how would a sci-fi game feel with a hip-hop soundtrack? Or a trance soundtrack? Or polka?

Creating a temporary soundtrack for your game will cut down on the guesswork for your composer and give him clear examples of what you want. Finding music is incredibly simple compared to the past, when we had to scour our CD collections or go into “the field” with microphone and recorders to get samples from the real world. But with the advent of iTunes, YouTube, Spotify, Pandora, and other music-finding websites, assembling tracks is a breeze: put in a couple of keywords and you’ll get hundreds, if not thousands, of results. You can have your team’s programmer insert this temp music into your game during production, but keep in mind there is always a danger that your team will really start to like (or hate) the temp tracks and complain if they are changed! Also, make absolutely sure you don’t leave any music in your game that you don’t have a license for. You may have to pay big money to use it or scrap all that work!

And the Beat Goes On…

Next, prepare a list of your musical needs. To determine this, figure out how many levels/environments/chapters/race tracks/unique encounters your game has. Each one of these levels will require background music—literally, music that plays in the background as a kind of audio backdrop for gameplay.

Traditionally, background music is themed toward the level. Spooky music on the haunted house level, medieval music for the castle level, jungle drums for the jungle level—you get the idea.

Background music tracks usually run for a few minutes and loop over again to save space in memory and composition time. Work with your music director to make sure the transition between the beginning and the end of the song sounds correct and isn’t marred by silence or an awkward change in tempo.

The next question to ask is whether you want—or more realistically, you can afford—to have background music on every level. You may have to reuse tracks throughout the game. For example, in Maximo vs. Army of Zin, we had two songs created for each world and alternated between them so players wouldn’t have to hear the same song twice in a row.

Instead of having a straightforward song-per-level system, you may want to work with your sound programmer and music director to create a dynamic score instead. In this method of scoring a game, music is broken up into themes that play when a certain situation arises. For example, dynamic music can kick in during combat to make a fight feel more exciting and fast paced. The main theme music will come back in once the fight is won.

Dynamic scoring is similar to the music convention leitmotif, in which a specific character or scenario has a specific musical theme associated with it. One of the most commonly known leitmotifs is from the Star Wars films. Darth Vader, Luke Skywalker, Yoda, and the Princess Leia/Han Solo romance all have unique themes that play whenever the characters are on-screen. If more than one is on screen, it’s up to your composer to switch between them without sounding too jarring.

The most commonly encountered dynamic score themes include

- Mystery—The player has entered a new and mysterious locale. A little bit of mysterious music can help set the mood.

- Warning—Sinister or menacing music plays whenever the player is entering a hazardous area or about to encounter enemies. This type of theme can be found in many horror games.

- Combat—Exciting music plays whenever the player is engaged in combat.

- Chase/fast movement—Chased by dinosaurs? Pursuing villains? Giant boulder hot on your heels? A fast-paced chase theme will make the action feel even more exciting.

- Victory—Be sure to sonically reward your players, even if it’s a “sting” (a very short piece of music) to let players know when a fight is over and they are victorious or to celebrate a successfully accomplished event in the game. The Legend of Zelda games have some great examples of rewarding players with music.

- Walking—While most games play “walking” music, I believe that if you play slow music, the player is going to move slowly. But if you make the music’s beat faster than the player can walk, it will motivate the player to move faster. In other words, remember this very important thing:

ALWAYS MAKE THE MUSIC MORE EXCITING THAN THE ACTION ON-SCREEN

Don’t forget to budget in music for your title screen, pause/options/save screen, game-over screen, or any bonus or minigames your games may have. Your opening theme is very important: it’s the first piece of music players hear and sets the stage for the rest of the game. I suggest using your best piece of music for the start screen to really get players excited about playing your game.

Environmental effects are the music of the world around us. Locations have their own special background sounds; a graveyard at night sounds very different from a city during lunch hour. Sometimes music can just be too overbearing or feel wrong for certain environments or games. Combining environmental effects with a dynamic score to punctuate action can be very effective. In Maximo: Ghosts to Glory, the hub levels were designed to have environmental effects to help players get into the mood of the locations while the gameplay levels had more traditional background music.

When is a sound not a sound? When it’s silence. Silence has a powerful effect on the listener. Often sound is used judiciously to indicate that something special is happening to the player or the world. It can be used to indicate great speed (when the music drops off as the player engages the boost in Burnout), intense action moments (as in “reflex time” in F.E.A.R.), suspense, or even a character’s failed attempt at humor.4

Sounds Like a Game to Me

Next, assemble a list of sound effects. Develop your sound effect lists as you develop the move sets of your characters and enemies. Start by cataloging the basic sound effects for your main character:

- Movement—Start with the sounds for walking and running on specific surfaces like stone, gravel, and metal, and splashing through water to make your character feel grounded in the world. Jumping, landing, rolling, and sliding all need sounds too to let players know they’ve pulled off the moves.

- Attacks—Making swings and kicks “swoosh” will make them sound more dynamic. Make unique attacks sound distinct, like Pac-Man’s “eating a ghost” or Mario’s jump/stomp.

- Impacts—A nice meaty “whack” will make a punch or kick feel more powerful. Weapons, spells, and explosions all need dynamic and loud sounds to make players know they’ve hit something or someone. Don’t forget object reaction effects like breaking wood, shattering glass, and clanging metal.

- Weapons—Guns bang, swords clang, and laser blasters “pew pew!” The bigger the weapon, the bigger the sound effect. Your weapons should sound as unique as they look; for example, the iconic hum of a light saber matches its distinctive visual.

- Hit reactions—“Oomph!” “Ow!” and “Aarrgh!” may sound funny while you are recording them, but they are some of the most important sounds in the game. Whenever players get hit, they need to know it and the sound will clue them in.

- Vocal cues—Need to communicate with the players? Use your character. Having your hero say “What’s this?” when he spots treasure or “That’s better!” after being healed will not only let players know what’s been accomplished or is possible, but provide a chance to add some character to your character. Don’t forget effort cues, such as grunts of exertion when pushing moveable blocks and pulling stubborn levers.

- Death—Nothing says “you’re dead” better than a good blood-curdling scream. Make sure you account for all the horrible ways to go, from a groan when getting slain to the gurgle of death by drowning to a long scream when plummeting off a cliff.

- Success—Use sound effects to indicate success to your players. Play a “sting” to let players know they’ve won and don’t forget to have your character celebrate vocally with a “woo-hoo!” or “yeah!”

For temporary sound effects, I suggest buying CD libraries from sound-effect providers like Sound Ideas5 or Hollywood Edge6. Their libraries have sounds for things you can’t even believe anyone would ever need—cougars sneezing or the hum of a nuclear reactor. They even have sound effects from some of the most popular Hollywood movies and TV shows. Even if you don’t have a dedicated sound effects designer on staff, sound effects are useful tools to have around the studio. Be prepared to spend many hours trying to find “the right” sound effect.

You can also find many sound effects online for free (though, of course, you should always check for copyright and so on—better to be sure than on the end of a lawsuit later). However, even with all these great resources online, sometimes you just can’t find the effect you need. This is the reason I turn to sound editing tools like Sound Forge7 or Vegas8. With these programs, I can quickly and easily mix together two or more sounds to get an idea across to a sound effects designer.

Decide whether you want your sound effects to be realistic or cartoony. This choice will generally be set by the theme of your game, but sometimes there are exceptions. Realistic sounds make the world feel grounded in reality, but sometimes the sounds can be too subdued. Cartoony sound effects are exaggerated and great for “video game-y” things like extra lives and treasure collection, but sometimes they are a little too “on the nose” and they risk taking the player out of the game’s world.

Make sure your sound designer is using sound to its greatest potential. Make sounds go “up” in pitch and tempo to make something sound positive, like collecting an extra life or completing a task. Make sound effects go “down” to reinforce negative and failure situations.

Sometimes your sound designer will have to “sweeten” a sound effect because the real-world version just doesn’t sound right. For example, I have found that breaking bones never sound right; they sound more like dry twigs cracking. Instead, my team “sweetened” the effect with the sound of a bowling ball cracking into pins.

When you are creating attack and reaction sound effects for your characters, work with your animators to determine timing. You want to make sure your sound effect doesn’t last longer or end before the animation does. After you determine the animation’s timing, create the sound effect to fit. Make sure your sound programmer knows what frame of animation the sound effect is supposed to play on.

Sounds can be used to give the player a warning or clue to something else in the game. The whistle of a falling bombshell can give the player enough of a chance to dive for cover. A crackle of electricity or ominous thrum of magical power will give the player pause when approaching a protected doorway. A player can search for an item like a lost pocket watch or misplaced cell phone by following the sound of its ticking or ringing.

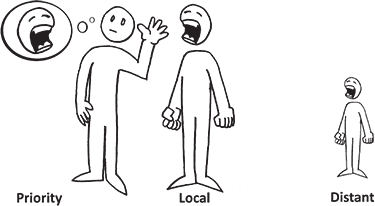

Be careful not to have too many sounds playing at once. To prevent sound effects from creating cacophony, you will have to prioritize them. Your sound programmer can help you designate sounds into three categories: local, distant, and priority.

- Local sound effects play when the player is close to the source of the sound effect. This may be a babbling brook, a ticking clock, a ringing phone, the hum of machinery, or the growls of an enemy. As the player gets further from the source, these sound effects fade away.

- Distant sound effects are sounds that the player can hear even if she is far from the sound’s source. These include explosions, a wolf’s howl, approaching vehicle engines, or the ominous thrum of a tower o’ doom.

- Priority sound effects are sounds that will always play regardless of where the player is. These are sounds that provide the player gameplay feedback, including loss of health; collection of treasures/goodies; score or combo increase; power-up or countdown timer; successful enemy hit; death; world interaction such as landing, collision, or weapon impacts; and footsteps/swim strokes/wing flaps.

When naming files for production, give your music and sound cues descriptive but short names so your teammates don’t have to guess what they are. For example, music for level 2 of your game may be called Lv2Song.wav, and the sound file for a variation on a robot enemy’s blaster shot may be roblast2.wav.

Sound not only is effective for communicating what is going on in the game, but also can be used for gameplay. Whole genres of games are centered around music and sound, from Dance Dance Revolution (Konami, 1998) to Band Hero (Activision, 2009) to Papa Sangre II (Playground Publishing B.V., 2013). When creating sound-based and music-based gameplay, don’t rely completely on the sound. Create visuals to echo the music and sound. You can never provide too many clues for the players, and you get the benefit of creating gameplay that can be played by impaired players.

- Short-term memory games like Simon (Milton Bradley, 1978) require players to memorize and repeat a short piece of music. It helps to have a visual component to the gameplay, not only to help players remember which notes to play but also to accommodate deaf (and tone deaf) players.

- Rhythm games like PaRappa the Rapper (SCE, 1996) Taiko: Drum Master (Namco, 2004), Rhythm Heaven (Nintendo, 2008), the Guitar Hero series, and the Tap Tap series require players to keep the beat in time to the music. Many of these games require or come with specific peripherals resembling instruments from guitars to maracas. When designing rhythm games, make sure you account for player fatigue. This is doubly true for games that use motion controllers or dance pads. You don’t want to give your players a heart attack! Provide mandatory breaks between songs and levels so players can catch their breath and keep playing.

- Pitch games have players sing in order to match a song’s pitch. These games require a microphone to play, as seen in the SingStar or Karaoke Revolution series of games.

- Music creation games blur the lines between music creation tool and game. Electroplankton (Nintendo, 2005) and Fluid (SCEI, 1998) feature charming player characters and dynamic on-screen activity; however, their end goals are not to win but to create and enjoy.

Other music games defy classification. Vib-Ribbon (SCE, 1999) creates platform-esque gameplay based on whatever CD players insert, creating different play experiences with every game. Rez (Sega, 2001) is a classic rail shooter with the added layer of players creating complex electronic music with each enemy they destroy. Battle of the Bands (THQ, 2008) is a rhythm game in which players play a musical tug-of-war (from disco to country, for example) as they launch attacks at each other.

As you can see, there are plenty of ways to use music and sound in gameplay. Don’t neglect them; they’re an important tool for a designer to use.