I return to the Cape on the eve of the new year. The summer is long gone. The sun looks as strong as ever, but it is made milky by the cold, its span over the horizon shortened. The days open late, become public, flicker, then close early, reclaiming their privacy.

As Dennis and Dory and I walk the beach at Herring Cove, the Arctic wind hits us full on. It bites at my face, tearing off the sun’s facile heat. I pull my scarf over my nose and stumble through the sand. Dennis kneels to the ground; we observe the rituals of the dead. A herring gull lies eviscerated, its guts pecked out by a glaucous gull which we saw at a distance, crouching over its cousin, ready and welcome protein. Dennis records the carcase on an index card. The blood, on pure white feathers, is strangely orange. The hole in its belly is big enough for me to wear the dead bird as a hat, should I so wish.

I throw Dory’s ball. She is naked, save for her collar. I worry that she might be shivering too. Her brow furrows and she cocks her head to one side as she asks me to throw the ball again. When we are with dogs, physicality is uncomplicated. They walk beside us as our outliers. Part of the human party, they are also our bridge with the natural world. They are our other. They are not cleverer than us, so we love them.

Like all animals, Dory has extraordinary eyes. Hers are fringed with pale lashes. No human could look so exquisite, or so feral, so unadorned. I can see why people once worshipped dogs. As we drive to the beach Dory perches on the armrest between Dennis and me, peering intently ahead, seeing and hearing things we do not see or hear. We only know because her ears rise or her eyes twitch. She knows where we are going. Perpetually expectant, as if every experience were a surprise, her body quivers with the excitement of just being alive. It is Funktionslust; an animal’s pleasure in doing what it does well, in being itself.

Dory is an import, like everyone else here, rescued from the backstreets of Miami. Now she scents foxes and chases balls, sometimes letting them roll into the surf, then staring at them as if daring me to go in after them. Her breeding, such as it is, may be Caribbean – a wild dog, the sort you see roaming Haitian beaches in packs and howling in the heat of the night – but her compact body seems suited to this winter landscape. Her neat flat coat is the colour of the dunes and the parched grass, although now she is growing fine silver hairs through her desert pelt. She never stops being, never stops running for her ball; I think her heart would burst before she let up the chase. Her life runs ahead of ours, speeding up as she races alongside us in another time zone. I’d like to talk to her in her voice, but like Wittgenstein and his lion, I wouldn’t understand what I might hear. Debbie, Dennis’s wife, says that sometimes Dory comes back from the woods shaking as if in fear, as if she’d seen something out there.

‘I am secretly afraid of animals,’ Edith Wharton, an erstwhile New Englander for all that she spent almost all her life in Paris, wrote in 1924, ‘– of all animals except dogs, and even of some dogs. I think it is because of the Usness in their eyes, with the underlying not-usness which belies it, and is so tragic a reminder of the lost age when we human beings branched off and left them; left them to eternal inarticulateness and slavery. Why? their eyes seem to ask us.’

The wonder is that all animals are not afraid of us. J.A. Baker, who spent the nineteen-sixties observing the wildlife of Essex, wrote of finding a heron on the winter marshes, trapped by its wings frozen to the ground. Baker dispatched the bird, humanely, watching the light leave its frightened gaze and ‘the agonised sunlight of its eyes slowly heal with cloud’.

‘No pain, no death, is more terrible to a wild creature than its fear of man,’ Baker concludes, in a deeply affecting passage, cited by Robert Macfarlane: ‘A poisoned crow, gaping and helplessly floundering in the grass, bright yellow foam bubbling from its throat, will dash itself up again and again on the descending wall of air, if you try and catch it. A rabbit, inflated and foul with myxomatosis … will feel the vibration of your footstep and will look for you with bulging, sightless eyes. We are the killers. We stink of death.’ Nature writing becomes war reporting. I remember the countryside of my childhood infected with that disease. In his ‘Myxomatosis’, written in 1955, Philip Larkin sees a rabbit ‘caught in the centre of a soundless field’, and uses his stick in an act of mercy. ‘You may have thought things would come right again | If you could only keep quite still and wait.’ My sister remembers our father having to do the same thing: the same terrifying eyes, the same dispatch.

We only play our roles; animals’ fates are our own. The fifteenth-century orator Pico della Mirandola, in his essay ‘On the Dignity of Man’, declared that to be human is to be caught between God and animal: ‘We have set thee at the world’s centre that thou mayest more easily observe what is in the world.’ Five hundred years later, the Caribbean writer Monique Roffey saw that ‘Animals fill the gap between man and God.’ That gap has widened. As John Berger observed, animals furnished our first myths; we saw them in the stars and in ourselves. ‘Animals came from over the horizon. They belonged there and here. Likewise they were mortal and immortal.’ But in the past two hundred years, they have gradually disappeared from our world, both physically and metaphysically: ‘Today we live without them. And in this new solitude, anthropomorphism makes us doubly uneasy.’

We expect animals to be human, like us, forgetting that we are animals, like them. They ‘are not brethren, they are not underlings’, the naturalist Henry Beston wrote from his Cape Cod shack in the nineteen-twenties; to him, animals were ‘gifted with extensions of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear … other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth’. That fear we see in their eyes is fear in alien eyes, eyes created for other realms.

Dennis, Dory and I walk on, around the cove. The tide peels back time, revealing frozen expanses of sand and waves of wrack. Skeins of briar and line have twined together like an elongated net constructed to catch primeval fish. I half expect to see a Neolithic family foraging on the beach. The landscape is moonlike, bone-scattered. Sere, stripped back by the winter, pallid and raw. Yet despite the intense cold – so barbarous it becomes a kind of warmth – the shore is full of life.

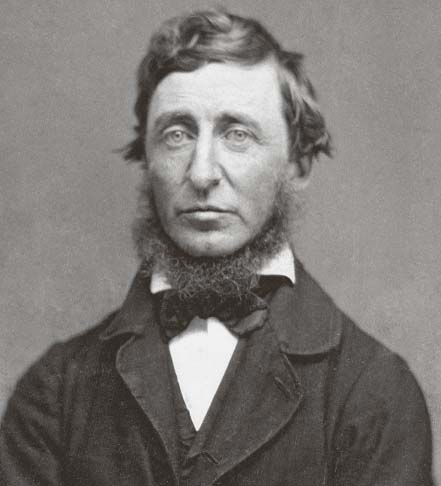

Everything is residual and tentative in the intertidal zone; a place belonging to no one, ‘a sort of chaos’, as Thoreau saw it, ‘which only anomalous creatures can inhabit’. Ribbed mussels, elegantly slipper-shaped in metallic blue and mauve, lie next to tiny flat stones, beige and green and purple and ringed with white. Through this tesserated pavement, samphire pushes up its stiff fingers; it’s called pickle grass here, a name that sums up its salty gherkin crunch. Stattice stands upright; even its everlasting purple flowers have been leached to a lifeless brown. Wind-burnt stalks of wild rose have long since lost their scent, but can still tear bare flesh. Pale-green lichens, barely alive at all, grow infinitesimally, stone flowers in this tundra-by-the-sea.

Dennis shows me his favourite tree: a stunted cedar like a large bonsai, spreading its skirt over a sandy hillock, as though claiming the site of an ancient tumulus. Impaled in a bayberry bush is the empty shell of a crab, probably dropped by a passing gull, still snapping its upraised claws at the sea across the dunes.

The estuary ahead widens with the falling tide. In the distance is Race Point Light. In between is Hatches Harbor, site of another lost settlement, like Long Point. Dennis thinks this was the place known as Helltown – an outpost for the outcasts of an already remote place, the human reverse of this heaven. Perhaps it resembled Billingsgate Island down at Wellfleet, which was reserved for young men, with its own whale-lookout, tavern and brothel.

Today there’s not a soul to be seen on this beach. But one winter morning I arrived here to see what looked like black sails a mile down the shore. As they dipped and swayed, I thought they belonged to particularly intrepid windsurfers. Only when I raised my binoculars did I see that the dark triangles were rising and falling, flexingly powered by something far bigger and stronger than a wetsuited human. I realised, with a sharp intake of cold breath, that they were the flukes of right whales, rolling in the waves.

Trying to remember the intricate geography of this outermost edge of the Cape, I cycled round to the fire road and as far as I could to the distant beach, abandoning my bike in the dunes. I would have run if the sand had allowed me. Cresting a low hill and stumbling through the marran grass, I suddenly regained the shore.

Below me lay a great crescent-shaped arena, occupied by hundreds of herring gulls. As I approached, they rose as one like a theatre curtain to reveal, barely twenty yards beyond the surf, half a dozen right whales engaged in what scientists call a surface active group, and what you and I might call foreplay.

I crouched there, doing my best not to disturb them. For an hour or more I watched their sleek blubbery bodies tumble and turn over one another in an intimate display, all the stranger and more physical for their nearness to the shore, as if they might be beached in the throes of their passion. But nothing could have curtailed those caresses. A harbour seal sat at the waterline watching too, hesitating to share the waves with these loved-up leviathans. It was a spectacle made more extreme by the cold, the sun, the wind and the silence as these gigantic animals, whose glossiness seemed to absorb all the light and the energy of the day, danced around one another in an amorous ballet whose choreography was determined only by their own sensuality.

There are no whales today, amorous or otherwise. Perhaps it is too cold even for their courtship. Dennis and I take shelter in the lee of a dune. For a few moments we’re out of the wind and can draw warm breath again. With the sun on our backs, our muscles relax. Hunched shoulders and curled hands loosen a little. As I look around, I realise that we are surrounded by bones – femurs and sternums, ribs and skulls – all tangled up in the salt hay.

We’re standing in a graveyard, an animal ossuary.

Poking about in the wrack we find a fox splayed in the tousled seaweed as if caught in the act of running, or of agony. Its flesh has been stripped away like an anatomical drawing. Clenched jaws display fine canines; ribs are picked clean. But its brush, the length of its body again, streams behind it, resplendent, rotting.

Nearby is a gannet. Or rather, its wings, six feet wide, great white-and-black contraptions discarded by some modern Icarus who’d fallen face-first into the grainy wet sand, leaving a pair of feet sticking out of the ground. A single gannet would fill my box bedroom back home; a bird on a giant scale. I hold the feathers up behind my back, as if the fledgling buds had burst through my skin, sprouting from my shoulderblades and unfolding to lift me into the air. I remember reading in my children’s encyclopaedia that my dreams of growing functional wings were impossible, because I’d have to grow a breastbone longer than my body. The accompanying illustration showed a man with his sternum hanging down between his legs, like some grotesque man-bird chimera drawn by Leonardo.

We turn back into the wind. The strand sweeps open and wide, connecting the inner bay with the outer sea. A beach that in summer is filled with sunbathers and anglers remains resolutely empty. I take off my clothes – no easy matter with frozen fingers and gloves, hat, scarf, jacket, fleece, two jumpers, boots and socks and jeans and long johns to contend with – and run into the navy-blue sea. It rolls on, and on. It looks like it did six months ago and five thousand years ago. It even feels the same. I treat it accordingly, borne up, singing, as though nothing has changed. As though everything will always be like this, and always was.

It is New Year’s Day.

Dennis and Dory walk on ahead. Glowing pink and shivering like a dog, my extremities as navy blue as the sea, I struggle back into my clothes, unable to do my jacket up with my numb fingers, and run after them. Dory looks back, apparently relieved. Did she think I’d been lost for good? In the car park Dennis has to rub my hands in his, making jokes about hoping that none of his friends will be driving by. My teeth chatter and my muscles shiver, shaking me back to life. Skin and bone burn like a hard cold flame. And they continue to burn and shake for an hour afterwards, till my body is convinced that the threat is over. Every swim is a little death. But it is also a reminder that you are alive.

Out at sea, hundreds of eiders and mergansers bob in the waves. They must be among the most hardy of all animals, these sea ducks, forever riding on the freezing water, resilient and resigned. At the north end of Herring Cove – in the lee of the rip of the Race where the sea turns dark as it becomes the ocean – is a sandbar which traps a temporary lagoon at high tide. In the heat of summer it’s a wonderfully warm place to swim, as languorous as a Mediterranean pool, although once I was horrified to see half a humpback beneath me, its great white knobbly flipper all but waving to me from the sandy bottom, as if its part-carcase were preserved by the salt water. Today the tide is running fast, and would quickly carry me out to sea.

This entire rounded tip of the Cape is a curling catchment, a beneficiary of long shore drift, perpetually shifting to reveal shipwrecks sticking out of the dunes. After winter storms have destroyed most of the car park – leaving its tarmac hanging in slabs like cooled lava over the sand – a chunk of ship, stirred out of retirement, emerges up the beach. Was it washed up or merely uncovered by the storms, lying there all along as I walked there, its knees and ribs beneath me, rubbed and eroded by the decades in which they have rolled around on the sea bed, waiting to be revealed like some vast wooden whale? It might be the remains of a twentieth-century vessel or a Viking longboat. The splintered timbers and curled ribs of oak lie cloaked in emerald-green weed, bolted pieces of something whose shape can only be guessed at.

‘The annals of this voracious beach! who could write them, unless it were a shipwrecked sailor?’ Thoreau wrote as he wandered from one end of the Cape to the other from 1849 to 1857, continually drawn back to this inbetween place. ‘How many who have seen it have seen it only in the midst of danger and distress, the last strip of earth which their mortal eyes beheld! Think of the amount of suffering which a single strand has witnessed! The ancients would have represented it as a sea-monster with open jaws, more terrible than Scylla and Charybdis.’

Walking towards Provincetown, Thoreau saw an arrangement of bleached bones on the beach ahead, a mile before he reached them; only then did he realise they were human, with scraps of dried flesh still on them. It was a sign Shelley had already foreseen, ‘On the beach of a northern sea’, as if in a premonition of his own demise, ‘a solitary heap, | One white skull and seven dry bones, | On the margin of the stones’.

On another walk Thoreau was told of two bodies found on the strand: a man, and a corpulent woman. ‘The man had thick boots on, though his head was off, but “it was along-side”. It took the finder some weeks to get over the sight. Perhaps they were man and wife, and whom God had joined the ocean-currents had not put asunder.’ Like the victims of Titanic, some bodies were ‘boxed up and sunk’ at sea; others were buried in the sand. ‘There are more consequences to a shipwreck than the underwriters notice,’ said Thoreau. ‘The Gulf Stream may return some to their native shores, or drop them in some out-of-the-way cave of ocean, where time and the elements will write new riddles with their bones.’ I see that same sea in his eyes, eyes that seem to see the sea forever; what it had found, and what it had lost.

Nearly four thousand ships have been wrecked along the Cape’s outer shore, from Sparrowhawk, which ran aground down at Orleans in 1626 and whose survivors were given refuge by the Pilgrims at Plymouth, to the British ship Somerset, which came to grief off Race Point in 1778 during the Revolutionary War, having fought in the Battle of Bunker Hill, foundering on the sandy bar off the Race. Twenty-one of its sailors and marines drowned, but more than four hundred were taken prisoner and sent to Boston. The Cape Codders escorting them gave up halfway, possibly worn down by their charges asking, ‘Are we there yet?’ Somerset has appeared every century since, in 1886, 1973 and 2010; a spirit ship, a beached Flying Dutchman. One writer in the nineteen-forties claimed that scores of people had seen ‘ghosts in the vicinity, ghosts of the British sailors’. The ship remains a sovereign vessel; perhaps I ought to reclaim it for my queen.

Meanwhile, many other wrecks lie out there like time machines. Thoreau saw the bottom of the sea as ‘strewn with anchors, some deeper and some shallower, and alternately covered and uncovered by the sand, perchance with a small length of iron cable still attached, – of which where is the other end?’

‘So many unconcluded tales to be continued another time,’ he wrote. ‘So, if we had diving-bells adapted to the spiritual deeps, we should see anchors with their cables attached, as thick as eels in vinegar, all wriggling vainly toward their holding-ground. But that is not treasure for us which another man has lost; rather it is for us to seek what no other man has found or can find.’

Wreckage and the wrecked: they merge into one, a mangling of man and land, of vessel and sea. I think of Crusoe cast up on the shore waiting for Friday’s footsteps, as the waves washed over a plaintive nineteen-sixties soundtrack; of Ishmael, another orphan, clinging to a coffin carved for Queequeg which provided his lifebuoy; of beached whales and beached humans. And I hear my father singing, ‘My bonny lies over the ocean, my bonny lies over the sea, my bonny lies over the ocean, O, bring back my bonny to me.’ I used to hear ‘body’ for ‘bonny’.

When Thoreau was visiting the Cape, an average of two ships every month would be lost in winter storms, especially on the deceptive bars off the Race at Peaked Hill, where shoulders of sand shadow the ocean’s edge. The roaring breakers catch white on the shifting shelf, luminous at night with the memory of the lives they’ve taken. And all this happened within sight of land.

‘Ship ashore! All hands perishing!’

These tempests were not conjured up by a magician, nor were there any sprites on hand to guide the survivors to safety. Commonly, sailors did not learn to swim – partly through superstition – ‘What the sea wants, the sea will have’ – and partly through practicality, knowing that adrift on the open ocean, their flailing would only prolong their fate. Any attempts to save the shipwrecked were often defeated by the elements. Would-be rescuers could only look on and wait until the storms subsided, by which time it was too late. All that was left to do was to salvage the wreck. In the eccentric museum at the Highland Light, housed in a 1906 hotel standing in the shadow of the lighthouse on the windblown headland, one of the most haunted places I have ever visited, a row of assorted chairs from many different disasters stands as a testimony to lost souls and salvaged domesticity: a sad line of mismatched seating, ranged along a wall at a students’ party. Upstairs, rooms with stable doors lined along a long, narrow and dimly-lit corridor; they still seemed filled with fitful guests, and something in the darkness down the end told me to get out.

Those who did make it ashore could die of exposure in this no-man’s-land, with no hope of reaching dwellings set deep inland, far from the raging sea. In 1797 the Massachusetts Humane Society set up ‘Humane-houses’, a series of huts equipped with straw and matches to provide survivors with warmth and shelter. Their echoes remain in the shacks still scattered through the dunes: rough constructions put together from grey beach-wood and timbers as though assembled by those lost sailors. Even in the town, salvaged ships’ knees propped up houses against the storms that brought the flotsam here, while Thoreau recorded fences woven with whale ribs.

Other dangers lurk in these countervailing waters, seen and unseen. Locals told Thoreau there was ‘no bathing on the Atlantic side, on account of the undertow and the rumour of sharks’, and he was warned by the lighthouse keepers at Truro and Eastham not to swim in the surf. They would not do so for any sum, ‘for they sometimes saw the sharks tossed up and quiver for a moment on the sand’. Thoreau doubted this, although he did see a six-foot fish prowling within thirty feet of the shore. ‘It was of a pale brown color, singularly film-like and indistinct in the water, as if all nature abetted this child of ocean.’ He watched it come into a cove ‘or bathing-tub’, in which he had been swimming, where the water was just four or five feet deep, ‘and after exploring it go slowly out again’. Undeterred, Thoreau continued to swim there, ‘only observing first from the bank if the cove was preoccupied’.

To the philosopher, this back shore seemed ‘fuller of life, more aërated perhaps than that of the Bay, like soda water’, its wildness lent an extra charge by that sense of life and death. Down at Ballston Beach, where Mary and I often swim out of season while seals and whales feed just off the sandbar, the powerful undertow seeks to pull us out. Not long ago a man swimming here with his son was bitten by a great white shark. Public notices instruct swimmers to avoid seals, the sharks’ true targets. Recently a fisherman showed me a photograph on his phone, taken at Race Point. A great white breaks the surfline, barely in the water, with its teeth around a fat grey seal. I place my quivering body in that tender bite, the ‘white gliding ghostliness of repose’ which Ishmael discerned, ‘the white stillness of death in this shark’. I still swim there, despite Todd Motta’s warning, ‘You don’t wanna go like that.’ The water is as hard and cold as ever. But one day, I think, I will not come out of it.

In his book The Perfect Storm, the story of a great gale which hit New England in 1991, Sebastian Junger details the way a human drowns. ‘The instinct not to breathe underwater is so strong that it overcomes the agony of running out of air.’ The brain, desperate to maintain itself to the last breath, will not give the order to inhale until it is nearly losing consciousness. This is the break point. In adults, it comes after about eighty seconds. It is a drastic decision, a final, fatal choice – like an ailing dolphin deciding to strand rather than drown because of something deep in its mammalian core; ‘a sort of neurological optimism’, as Junger puts it, ‘as if the body were saying, Holding our breath is killing us, and breathing in might not kill us, so we might as well breathe in.’

Drawing in water rather than air, human lungs quickly flood. But lack of oxygen will have already, in those last seconds, created a sensation of darkness closing in, like a camera aperture stopping down. I imagine that receding light, being drawn deep, caught between the life I am leaving and the eternity I am entering. We know, from those who have come back from death, that ‘the panic of a drowning person is mixed with an odd incredulity that this is actually happening’. Their last thoughts may be, ‘So this is drowning,’ says Junger, ‘So this is how my life finally ends.’

And at that final moment, what? Who will take care of my dog? What will happen to my work? Did I turn the gas off? ‘The drowning person may feel as if it’s the last, greatest act of stupidity in his life.’ One man who nearly drowned, a Scottish doctor sailing by steamship to Ceylon in 1892, reported the struggle of his body as it fought for the last gasps of oxygen, his bones contorting with the effort, only to give way to a strangely pleasant feeling as the pain disappeared and he began to lose consciousness. He remembered, in that instant, that his old teacher had told him that drowning was the least painful way to die, ‘like falling about in a green field in early summer’.

It is that euphoria which offers an aesthetic end, leaving the body whole and inviolate, a beautiful corpse, as if the sea might preserve you for eternity. There is an inviting compulsion about falling into the sea, because it seems such an unmessy, arbitrary way to go. You’re there one minute, in another world the next; a transition, rather than a destruction.

On his journey from New York to England in 1849 on the ship Southampton, Melville saw a man in the sea. ‘For an instant, I thought I was dreaming; for no one else seemed to see what I did. Next moment, I shouted “Man overboard!”’ He was amazed that none of the passengers or sailors seemed very anxious to save the man. He threw the tackle of the quarter boat into the water, but the victim could not, or would not, catch hold of it.

The whole incident played out in a strange, muted manner, as if no one really noticed or cared, not even the man himself.

‘His conduct was unaccountable; he could have saved himself, had he been so minded. I was struck by the expression of his face in the water. It was merry. At last he drifted off under the ship’s counter, & all hands cried, “He’s gone!”’

Running to the taffrail, Melville watched the man floating off, ‘saw a few bubbles, & never saw him again. No boat was lowered, no sail was shortened, hardly any noise was made. The man drowned like a bullock.’

Melville learned afterwards that the man had declared several times that he would jump overboard; just before his final act, he’d tried to take his child with him, in his arms. The captain said he’d witnessed at least five other such incidents. Even as efforts were made to save her husband, one woman had said it was no good, ‘& when he was drowned, she said “there were plenty more men to be had.”’

Half a century later, in 1909, Jack London – who was a deep admirer of Melville – published Martin Eden, his semi-autobiographical account of a rough young sailor who becomes a writer. London, the son of an astrologist and a spiritualist, was born in San Francisco in 1876. He had led an itinerant life as seaman, tramp and gold prospector. He was a self-described ‘blond-beast’, a man of action, the first person to introduce surfing from Hawaii to California; he also became the highest-paid author in the world with books such as The Call of the Wild, The Sea-Wolf and White Fang. But the proudest achievement of his life, he said, was an hour spent steering a sealing ship through a typhoon. ‘With my own hands I had done my trick at the wheel and guided a hundred tons of wood and iron through a few million tons of wind and waves.’

London wrote Martin Eden while sailing the South Pacific, trying to escape his own fame; the New York Times had reported FEAR JACK LONDON IS LOST IN PACIFIC when he didn’t arrive as expected at the Marquesas, the remote islands where Melville himself had jumped ship in 1840. In London’s book, Eden, the first man to himself, cynical about his new-found celebrity, contemplates suicide in the early hours of the morning. He thinks of Longfellow’s lines – ‘The sea is still and deep; | All things within its bosom sleep; | A single step and all is o’er, | A plunge, a bubble, and no more’ – and decides to take that step. Midway to the Marquesas, he opens the porthole in his cabin and lowers himself out.

Hanging by his fingertips, Eden can feel his feet dangling in the waves below. The surf surges up to pull him in. He lets go.

Everything in his strong constitution fights against this act of self-destruction. As he hits the water, he begins to swim; his arms and legs move independently of his will, ‘as though it were his intention to make for the nearest land a thousand miles or so away’. A tuna takes a bite out of his white body. He laughs out loud. He tries to breathe the water in, ‘deeply, deliberately, after the manner of a man taking an anaesthetic’. But even as he pushes his body down vertically, sinking like ‘a white statue into the sea’, he is pushed back to the surface, ‘into the clear sight of the stars’.

Finally, Eden fills his lungs with air and dives head-first, past luminous tuna, plunging as deep as he can. His body bursts with bubbles. He is aware of a flashing bright light, like a lighthouse in his brain. He feels he is tumbling down an interminable stairway. ‘And somewhere at the bottom he fell into darkness. That much he knew. He had fallen into darkness. And at the instant he knew, he ceased to know.’ Eden, this handsome sailor whose body is described as solid, hewn and tanned, is compressed by the weight and darkness of the sea, falling asleep on its bed, so still that a shake of the shoulder could not wake him. He has been sacrificed to his own ideals, his own masculinity. London said his novel was about a man who had to die, ‘not because of his lack of faith in God, but because of his lack of faith in men’. His writing is vivid enough to recall his own youthful attempt to drown himself in San Francisco Bay, when ‘some maundering fancy of going out with the tide suddenly obsessed me’. ‘The water was delicious,’ he wrote. ‘It was a man’s way to die.’

There have been moments in the water when I felt they might be my last. One dark November afternoon I swam off Brighton, under the shadow of its burnt-out West Pier, while a murmuration of starlings eddied about the rusting ribs above me. I hadn’t realised, until I entered the water, how strong the undertow was; or, as I swam out, how it would take me up, take control and tip me head over heels before dragging me back out.

I’d lost my grip on the world. The heavy pebbles of the beach rolled beneath me, and in the falling darkness, as the lights came on along the esplanade, I thought how banal it would be to die within sight of a dual carriageway and a row of fish-and-chip shops and burger bars. And I wonder, when I am dead, what thoughts will be left in my head, like the black box recorder of a downed plane.

Another time, on Dorset’s West Bay, under its towering cliffs, the tow played a similar trick. I quickly realised what I had done, and tried to climb out. Again I was turned over for my impudence and thrown face-down on the shingle, my features squashed like a peat bog man. Mark told me this was the way surfers smashed their faces, and that evening in town, someone warned me that the beach was notorious, and that only a few months before a young man had drowned there.

And I thought about Virginia Woolf’s body being taken out, as if her death were a culmination of all her words, moving inexorably towards the sea.

It’s odd to return to the books I was required to read at college, their unbroken backs covered in clear plastic to protect them against some future event, preserving them for a time when I would actually understand them, although their pages are now vignetted in brown, as if the sun had penetrated their closed edges. They wait for me to open them, to bring them back to life, familiar and strange and dangerous, as though I were reading them for the first time.

To the Lighthouse is set in the Hebrides, but it draws on Woolf’s childhood holidays in Cornwall, and memories of her Victorian mother. Mrs Ramsay hears and feels the waves as they ‘remorselessly beat the message of life’; they make her think of ‘the destruction of the island and its engulfment in the sea’. At night, as her guests sit around the candlelit table, she looks out of the uncurtained windows through the dark rippling glass – ‘a reflection in which things waved and vanished, waterily’, as if all the world was at sea – and she thinks of herself as a sailor who, if the ship had sunk, ‘would have whirled round and round and found rest on the floor of the sea’. In the distance, the lighthouse stands tall and white on a rock.

The water possessed an ambivalent power for Woolf. One moonlit night, when she was a young woman, she and Rupert Brooke swam naked in the river Cam at Byron’s Pool, named after the poet, who had swum there when he was at Cambridge. Brooke was proud of his improbable and Byronic ability to emerge from the water with an erection. Later, Woolf joined Brooke and his Neo-Pagans, as she called them, when they camped on Dartmoor and swam in the moorland river. Virginia, both prim and liberated, did not quite feel at ease with their attempts to commune with nature; her future biographer Hermione Lee would lament the fact that the nude photographs taken on that occasion did not survive.

Woolf – only an extra O away from being an animal herself, a virgin wolf – had a relationship with the natural world that was both paradoxical and predatory. Nature was unfeeling, going about its business. The beach was no consolation. In To the Lighthouse, after a scene in which ‘the sea tosses itself and breaks itself, and should any sleeper fancying that he might find on the beach an answer to his doubts, a sharer of his solitude, throw off his bedclothes and go down by himself to walk on the sand … to ask the night those questions as to what, and why, and wherefore, which tempt the sleeper from his bed to seek an answer’ – we discover, almost in passing, that Mrs Ramsay has died. In the aftermath, the sea seems to take over the house, as death has overtaken the Ramsays. Of their eight children, Andrew is killed in the war and Pru dies in childbirth. Virginia’s own mother, Julia, died aged forty-nine, and her brother Thoby died of typhoid fever when he was twenty-six years old. For Woolf, the water meant death as well as life.

What remains of the Ramsay family and their friends return ten years later. The house, once so full, has stood empty; the elements threaten to overtake it. We expect the deluge of war to have washed it away. But it is rescued by the housekeeper, to whom Mrs Ramsay appears as a ‘faint and flickering’ image, a kind of ghost, ‘like a yellow beam or the circle at the end of a telescope, a lady in a grey cloak, stooping over her flowers’. The memory is electric, almost cinematic: Virginia’s mother Julia was photographed by her aunt, Julia Margaret Cameron, more than fifty times, her profile turned this way or that, her smooth hair, glaucous eyes and strangely vacant face the same as her daughter’s, wearing a black gown, white cuffs and collar, caught on the path at Freshwater, moving in her dark clothes; then not moving, stilled in the instant, then moving on, ‘the Star like sorrows of Immortal Eyes’.

So too Virginia would pose for Vogue in her mother’s dress in 1924, ravished by a Pre-Raphaelite sea, acting as her own sepia ghost, rehearsing her last scene, floating down the Ouse as Ophelia, ‘her clothes spread wide, | And mermaid-like, awhile they bore her up’. After her father died, and Virginia and her orphaned siblings moved to Bloomsbury, she hung Cameron’s fantastical portraits of famous men and fair women in the hallway as an ironic gesture. For all her modernism, Virginia was anchored in a Victorian past, shaped and damaged by its history, and her own.

Those remote summers by the sea would remain with her. In her book, the ferocious Atlantic becomes a character itself, like the moor in Wuthering Heights or the whale in Moby-Dick (of which she owned two copies, and which she read at least three times). ‘In both books,’ she wrote in an essay on Brontë and Melville in 1919, ‘we get a vision of presence outside the human beings, of a meaning that they stand for, without ceasing to be themselves.’ Woolf’s white lighthouse is Melville’s white whale; an impossible mission over unfathomable waters.

Cam, the riverishly-named youngest Ramsay daughter, dangles her hand in the waves as she and her brother reluctantly accompany their father on the long-postponed trip to the lighthouse. Out at sea they become becalmed, and in her dreamy, deceptive state, Cam’s mind wanders through the green swirls into an ‘underworld of waters where the pearls stuck in clusters to white sprays, where in the green light a change came over one’s entire mind and one’s body shone half transparent enveloped in a green cloak’. As blank and ever-changing as it is, as calm or crazed, the sea could embody ecstasy or despair; it was a mirror for Woolf’s descent into madness, a process made profound by knowing what was about to happen. She might have been enchanted by Ariel. ‘I felt unreason slowly tingling in my veins,’ she would say, as if her body were being flooded by insanity or filled with strange noises: birds singing in Greek; an ‘odd whirring of wings in the head’.

Cam seems besieged by the sea, by a numb terror and ‘a purple stain upon the bland surface as if something had boiled and bled, invisibly, beneath’. Meanwhile ‘winds and waves disported themselves like the amorphous bulks of leviathans whose brows are pierced by no light of reason’. Eventually the Ramsays reach the lighthouse, but even that epiphany is darkened by the fact that they pass over the place – if water could be said to have a place – where their fisherman had once seen three men drown, clinging to the mast of their boat. All the while their father, as gloomy and tyrannical as Ahab, dwells on William Cowper’s doomy poem, ‘The Castaway’: ‘We perish’d, each alone: | But I beneath a rougher sea, | And whelm’d in deeper gulfs than he.’ When, as a young woman, Virginia had heard of the fate of Titanic, she imagined the ship far below, ‘poised half way down, and become perfectly flat’, and its wealthy passengers ‘like a pancake’, their eyes ‘like copper coins’. Later, to another friend, she said, ‘You’ll tell me I’m a failure as a writer, as well as a failure as a woman. Then I shall take a dive into the Serpentine, which, I see, is 6 feet deep in malodorous mud.’ To her even the bridge over the monstrously-named inland sea in a London park was a white arch representing a thousand deaths, a thousand sighs.

While writing To the Lighthouse, Woolf read of another disaster. On the first ever attempt to fly westbound across the Atlantic, the wealthy Princess Löwenstein-Wertheim had perished, along with her pilot and co-pilot. ‘The Flying Princess, I forget her name, has been drowned in her purple leather breeches.’ In her mind’s eye Virginia saw the plane running out of petrol, falling upon ‘the long slow Atlantic waves’ as the pilots looked back at the ‘broad cheeked desperate eyed vulgar princess’ and ‘made some desperate dry statement’ before a wave broke over the wing and washed them all into the sea. It was an arch nineteen-twenties scene; Noël Coward out of The Tempest. ‘And she said something theatrical I daresay; nobody was sincere; all acted a part; nobody shrieked.’ The last man looked at the moon and the waves and, ‘with a dry snorting sound’, he too was sucked below, ‘& the aeroplane rocked & rolled – miles from anywhere, off Newfoundland, while I slept in Rodmell’. Ten years later Virginia drove past a crashed aeroplane near Gatwick and learned afterwards that three men on board had died. ‘But we went on, reminding me of that epitaph in Greek anthology: when I sank, the other ships sailed on.’

The sea echoes over and over again in Woolf’s work, with the rhythm of moon-dragged tides. Having finished To the Lighthouse, she entered a dark period, exhausted, fighting for breath; yet out of it she sensed the same vision of presence beyond being that she had seen in Brontë and Melville; something ‘frightening & excited in the midst of my profound gloom, depression, boredom, whatever it is: One sees a fin passing far out.’ It was a deep, cryptic image, hard to diagnose or discern, as she confessed to her diary a year later, summoning ‘my vision of a fin rising on a wide blank sea. No biographer could possibly guess this important fact about my life in the late summer of 1926: yet biographers pretend they know people.’

As a boy on holiday in Dorset, I saw a distant glimpse of dolphins, arcing through the water off Durleston Head, a rocky promontory held out in the grey English Channel. As a girl holidaying in Cornwall, Woolf had seen cetaceans too: one family sailing trip in the summer of 1892 ‘ended hapily [sic] by seeing the sea pig or porpoise’; her nickname for her sister Vanessa, with whom she was extraordinarily close, was Dolphin. And in The Waves, the book that followed To the Lighthouse, and which became her most elegiac, internalised work, her vision returned as one character watches a fin turn, ‘as one might see the fin of a porpoise on the horizon’.

The sickle-sharp shape seen against the featureless sea – something there and not there – is the emblem of knowing and unknowingness. It is not the real dolphin leaping through the waves, or the curly-tailed, boy-bearing classical beast, or the mortal animal sacrificed and stranded on the sand, but something subtly different: the visible symbol of what lies below, swimming through the writer’s mind as a representation of her own otherness. In Woolf’s play Freshwater, a satire on the bohemian lives of Julia Margaret Cameron and Tennyson on the Isle of Wight, a porpoise appears off the Needles and swallows one of the characters’ engagement ring; in The Years, ‘slow porpoises’ appear ‘in a sea of oil’; and in a vivid episode in Orlando, a porpoise is seen embedded in the frozen Thames alongside shoals of eels and an entire boat and its cargo of apples resting on the river bed with an old woman fruit-seller on its deck as if still alive, ‘though a certain blueness hinted the truth’.

Woolf made a sensual connection between the porpoise and her lover. Vita Sackville-West, tall and man-womanish – a kind of Elizabethan buccaneer clad in her brown velvet coat and breeches and strings of pearls and wreathed in the ancestral glamour of her vast house, Knole, where the stags greeted her at the door and even wandered into the great hall – morphed from she-pirate into a gambolling cetacean for Virginia. It was a dramatic appropriation, dragging the strange into the familiar. Perhaps it was no coincidence that Shakespeare – for whom gender and species were fluid states – often linked whales, living or stranded, with royal princes; or that Woolf’s name evoked both the queen and her colony.

At Christmas 1925 the two women, who’d just spent their first night together, went shopping in Sevenoaks, where they saw a porpoise lit up on a fishmonger’s slab. Virginia elided that scene with her elusive paramour out of the sixteenth century into the twentieth, Vita standing there in her pink jersey and pearls, next to the marine mammal, both curiosities. ‘I like her & being with her, & the splendour,’ Woolf admitted to her diary like a schoolgirl, ‘she shines … with a candlelit radiance, stalking on legs like beech trees, pink glowing, grape clustered, pearl hung … so much in full sail on the high tides, where I am coasting down backwaters.’ ‘Aint it odd how the vision at the Sevenoaks fishmongers has worked itself into my idea of you?’ she wrote to Vita two years later, and proceeded to replay the image at the end of Orlando, when her gender- and time-defying hero/ine returns home in 1928 – ‘A porpoise in a fishmonger’s shop attracted far more attention.’ Meanwhile Vita made her own boast, of ‘having caught such a big silver fish’ in Virginia.

Orlando is an updated fairy tale which collapses four centuries of English history into a whimsical modernist fantasy. History rushes by, briefly arrested in close-up, acid-trip details: the grains of the earth, the swelling river, the long still corridor in Orlando’s sprawling palace which runs as a conduit into time, as if a production of The Tempest were being acted out silently at the end of its wood-panelled tunnel. Orlando is both player and prince, like Elizabeth, or Shakespeare’s Fair Youth, Harry Southampton, animal and human, a chimera out of a Jacobean frieze, ‘stark naked, brown as a satyr and very beautiful’, as Virginia saw Vita. As the deer walked into Knole’s great hall, so Orlando moves through species, sex and time; she too might become a porpoise strung with baroque pearls, animating the unknown sea.

There is more than a little of Melville’s playfulness in Orlando. Woolf read Moby-Dick in 1919, in 1922, and again in 1928. In 1921, in her two-paragraph prose poem ‘Blue and Green’, she wrote a remarkably vivid picture of a part real, part fantastical whale inflected with her recent reading: ‘The snub-nosed monster rises to the surface and spouts through his blunt nostrils two columns of water … Strokes of blue line the black tarpaulin of his hide. Slushing the water through mouth and nostrils he sings, heavy with water, and the blue closes over him dowsing the polished pebbles of his eyes. Thrown upon the beach he lies, blunt, obtuse, shedding dry blue scales.’ In Orlando, she uses a line from a sea shanty in one of Melville’s chapters, ‘So good-bye and adieu to you, Ladies of Spain,’ and his influence is felt elsewhere in the book, not least when, halfway through a long sentence set in the seventeenth century, Woolf informs her reader of the precise moment at which it was written, ‘the first of November 1927’, in the same way that Melville time-codes his chapter ‘The Fountain’ ‘down to this blessed minute (fifteen and a quarter minutes past one o’clock P.M. of this sixteenth day of December, A.D. 1850)’. ‘For what more terrifying revelation can there be than it is the present moment?’ Woolf wrote. ‘That we survive the shock at all is only possible because the past shelters us on one side and the future on another.’ She even had an active interest in science fiction, prophesying a machine that could connect us with the past, as well as a telephone which could see.

As Orlando leaves the eighteenth century and changes sex, her Shakespearean origins are reflected in the nineteenth-century weather: ‘the clouds turned and tumbled, like whales’, reminding her, like Keats, ‘of dolphins dying in Ionian seas’, while the carriages in Park Lane conjure up ‘whales of an incredible magnitude’. In these ‘unfathomable seas’ the natural world takes on an erotic charge. For Ishmael, Melville’s unreliable narrator, the shape-shifting sperm whale is freighted with the ocean’s obscure desire, while the sea reflects Narcissus examining his own beauty. As the equally unreliable Orlando reaches the eighteen-forties – when both Moby-Dick and Wuthering Heights took shape – she declares, like Cathy, ‘I have found my mate. It is the moor. I am nature’s bride.’ And in another Melvillean image, she sees a ship sailing through the bracken while her lover recites Shelley and watches it cresting a white wave which, like the Serpentine bridge and the white whale, represents a thousand deaths. (It is telling that Woolf compared George Duckworth, her half-brother and abuser, to ‘an unwieldy and turbulent whale’.)

As a writer, Virginia felt she had to conduct a transaction with the spirit of the age; and so she played with the ages – an artist has to stand outside like a seer, or in between, like a medium. Slowed down compared to the speeding time suffered by the humans around her, Orlando lives for four hundred years, as long as an Arctic whale; like Moby Dick, she too seems immortal and ubiquitous – ‘for immortality is but ubiquity in time’, as Melville says. Perhaps she cannot die. At the end of the book, Orlando drives her fast car back to her country house. Swapping her skirt for whipcord breeches and a leather jacket, she wanders through her estate to a pool which is partly the Serpentine, partly the sea, ‘where things dwell in darkness so deep that what they are we scarcely know … all our most violent passions’. It is her version of Gatsby’s orgiastic future that recedes before him, beating against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past, just as Ahab’s ship sinks in a sea rolling on as it had done for five thousand years – its biblical age.

In fiction and reality and in between, Woolf continued to delve in a pre-Darwinian, aquatic uncanny. During a visit to Loch Ness in 1938, she met a charming couple at a lochside inn ‘who were in touch … with the Monster. They had seen him. He is like several broken telegraph posts and swims at immense speed. He has no head. He is constantly seen.’ And in another gothic episode, like one of the gruesome Victorian family stories she liked to retell, Virginia recorded the fate of Winifred Hambro, wife of a wealthy banker, who drowned in the loch when their speedboat burst into flames. Her husband and sons swam to safety, but despite being a good swimmer, and pulling off her skirt, she sank. ‘Loch Ness swallowed Mrs Hambro. She was wearing pearls.’ It was said that because of its steep sides, the loch never gave up its dead: divers were sent down to recover the body and the pearls, which were worth thirty thousand pounds, but reported only a story of a sinister underwater cave, warm and black. In To the Lighthouse, the artist Lily imagines throwing herself off the cliff and drowning while looking for a lost pearl brooch on the beach. The lustrous pearls, lit from within, slide into the abysmal darkness; the sensual product of the sea, they once more become the eyes of the dead.

That same year, 1938, Woolf dwelt on something else elusive. In her essay ‘America, Which I Have Never Seen’, she looks out over the ocean to a continent she will never visit, sending her ‘Imagination’ to explore it for her, like Odin’s all-seeing ravens or an updated Ariel, ‘to fly, | To swim, to dive into the fire, to ride | On the curl’d clouds’.

‘Sit still on a rock on the coast of Cornwall,’ her spirit-familiar tells her, ‘and I will fly to America and tell you what America is like.’ Passing fishing boats and steamers, soaring over Queen Mary and several aeroplanes, Imagination reports back: ‘The sea looks much like any other sea; there is now a shoal of porpoises cutting cart wheels beneath me.’ She makes landfall, like an exhausted swallow or monarch butterfly arriving on the Cape. Then the Statue of Liberty looms, and New York: a century on from when Ishmael looked over its harbour, it is now overlooked by ‘immensely high towers, each pierced with a million holes’; each a white lighthouse of its own.

This sea is as freighted as any in Moby-Dick or The Tempest, and it suffuses Woolf’s most intensely felt work. The Waves is flooded with a stream of consciousness, invoking the voices Virginia heard in her head on the days and nights when her condition drove her to talk unintelligibly for hours on end, and when she lay confined to her bed in her house by the river at Richmond, ‘mad, & seeing the sunlight quivering like gold water, on the wall, listening to the voices of the dead’.

The book follows six characters, loosely based on Woolf’s siblings and friends, as they move from schooldays to adulthood, drawn together by the loss of their dead friend Percival, just as Virginia lost her brother Thoby. Each section is separated by descriptions of the sea which are more painterly or musical than literary, redolent of Turner’s seascapes or Britten’s sea interludes. Surging and ebbing, borne on the immemorial Thames and its intimations of the ocean beyond, the water seeps into lives landbound by London. It is the same refined, barbaric world undermined by Conrad’s heart of darkness and Eliot’s waste land; where the river sweats oil and tar, and barges drift past Greenwich Reach to Gravesend. Bernard, Susan, Rhoda, Neville, Jinny and Louis speak in the voices of the long or recently dead, voices submerged by civilisation and the city-drowned suburbs, crushed by their pressure. They long to escape. They speak as their creator spoke, in perfectly composed sentences which sound like quotations from their own fiction. ‘One was compelled to listen even when she only called for more milk,’ wrote a friend after spending an evening with Virginia. ‘It was strangely like being in a novel.’

‘Here, in this room, are the abraded and battered shells cast on the shore,’ Jinny says. Louis – for whose voice Woolf drew on Eliot, whom she saw as a slippery eel – is summoned to ‘wander to the river, to the narrow streets where there are frequent public houses, and the shadows of ships passing at the end of the street’. Bernard feels the world moving past him like ‘the waves of the sea when a steamer moves’; he dreams of going to Tahiti and watching a fin on the horizon. All along the river, time leaks; the Thames is a time machine. We might be standing by Orlando’s side as she looks out from her Blackfriars house, past the empty warehouses of empire once filled with colonial plunder and on with the heaving tide, swelling high and brown along the Embankment while twenty-first-century tourists pass by.

This city, through which Virginia wandered in a state of inner loneliness, is a place of ritual and sacrifice as much as of trade and progress, coursed with a relentless tide of humanity undone by death, as though it would flow backward out of time. ‘It was this sea that flowed up to the mouth of the Thames,’ as she wrote in The Voyage Out, ‘and the Thames washed the roots of the city.’ And as the characters of The Waves watch the steamers sail, they bear witness to the same sea-reach where Marlow saw that ‘we live in the flicker, but darkness was here yesterday’.

Under the pavements of Piccadilly – ‘the descent into the Tube was like death’ – Jinny feels the trains running ‘as regularly as the waves of the sea’. Neville – based on Woolf’s whinnying intimate, Lytton Strachey – reads a poem, and ‘suddenly the waves gape and up shoulders a monster’ (an image to be replayed in Iris Murdoch’s The Sea, the Sea, with its own Tempest-inflicted story); he sees his life as a net lifting ‘whales – huge leviathans and white jellies, what is amorphous and wandering … I see to the bottom; the heart – I see to the depths.’ And in a passage auguring her author’s own fate, Rhoda imagines launching a garland of flowers over a cliff, beyond ‘the lights of the herring fleet’, to ‘sink and settle on the waves’, and she with it, like Melville’s Billy Budd or Hamlet’s Ophelia. ‘The sea will drum in my ears. The white petals will be darkened with sea water. They will float for a moment and then sink. Rolling me over the waves will shoulder me under. Everything falls in a tremendous shower, dissolving me.’

This is a fractured, brutal sea, far darker than Orlando’s brocaded dreams. It is ‘violent and cruel’, a new myth enacted under a sky ‘as dark as polished whalebone’. Woolf’s prose catches that dark and light, washed over by ‘water that had been cooled in a thousand glassy hollows of mid-ocean’, inundating and uncaring, everything and nothing: an empty eternity, ‘no fin breaks the immeasurable waste’. The modernists had found their sea in Melville, an alternative, absolute power with which there is no dialogue, no debate. It stood beyond the depredations of a violent and cruel century, yet was filled with stories like those wreaths cast into its depths, dashed with votive offerings and ghosts of the living and the dead: ‘There are figures coming towards us. Are they men or women? They still wear the ambiguous draperies of the flowing tide in which they have been immersed.’ The shores are patrolled by phantoms abandoned to the waves. ‘It is strange how the dead leap out on us at street corners, or in dreams.’

As we sit around her stove, peering into its glowing interior, Pat tells me she remembers how she has lost good friends, but they came to see her as they died, even though they were far away.

She raises her foot to kick a new chunk of wood into the furnace.

‘Do you have visitors like that?’ she asks me. ‘They do the rounds before they die.’

I see them walking up the beach to her, nonchalantly passing on the news of their passing. I remember walking on another beach with my mother by my side, waiting to see the sun slip behind the shadow of the earth at noon. I remember her greyness at the end, when all colour had been leached out of her, out of her red hair and her high cheekbones, lying there, so still, in her hospital bed. And I wonder if I’ll see my loved ones, pacing up the sand or peering round my door as the latch lifts and clicks.

At night, Pat lies in her wooden, boxlike bed, face up. Even in her unconscious she is open to the sea just beyond her window. Does she dream of her dogs, or do her dogs dream of her?

‘My dreams got too heavy,’ she tells me, as the stove warms my outstretched hands with its iron glow. ‘So I stopped having them.’

By the water, terror and beauty go hand in hand. The Pilgrims who came to the Cape – sailing at two miles an hour rather than travelling in the instant accomplished by Woolf’s Imagination – found this brave new world a ‘naked and barren’ place. Soon after Mayflower anchored off what would become Provincetown, Dorothy Bradford, wife of their leader, William Bradford, fell overboard and drowned in the harbour.

This naked and barren coast is now studded with lighthouses, symbols of the lost and found. They offer haven and home, safety and hope, welcome and melancholy. They’re the land’s last markers, measuring out the Cape’s confusing asymmetry; you never really know where you are here, no matter how much you might consult the compass or look to the sun. You lose your bearings, find them, then lose them again. But the lighthouses hardly help. They’re invested with the strangeness of the sea, only emphasising our separation. For Mrs Ramsay, the lighthouse represents ‘our apparitions, the things you know us by’. She looks out ‘to meet that stroke of the lighthouse, the long steady stroke … until she became the thing she looked at’. As she wrote her novel, Virginia saw Vita as a lighthouse, ‘fitful, sudden, remote’.

Once fuelled by the whales on whom their beams still fall, these towers of light map out the Cape like one of those illuminated museum displays where you’d press a button to turn on a little wavering bulb. They flash their characteristics, coded signatures like a cetacean’s metronomic clicks: from the unseen light at Nauset, which reveals itself only by an anonymous ten-second sweep over the horizon as if it were itself lost, to the six-second signal of the Highland Light, where Thoreau was entertained by the keeper in his ‘solitary little ocean-house’, and where his bedchamber was flooded with light ‘and made it bright as day, so I knew exactly how the Highland Light bore all that night, and I was in no danger of being wrecked’; and on, from Long Point’s green dash every four seconds to Wood End’s red twitch every ten, looking out over the waters in which in the US submarine S-4 was accidentally hit by a coastguard vessel, sinking one hundred feet to the sandy bottom in the winter of 1927. Wood End Light was no use to it now, down there in the darkness.

Most of the forty-strong crew died – not drowned, but poisoned by bad air like canaries – and storms prevented the rescue of the six survivors trapped in the torpedo room, the only remaining air pocket. A second submarine, S-8, was able to communicate with them by an oscillator attached to the hull of their vessel, transmitting Morse code through the metal skin that separated the men from the world above and the sea around them.

‘Is there any gas down there?’

Their officer, twenty-five-year-old Lieutenant Graham Fitch, replied, ‘No, but the air is very bad. How long will you be?’

‘How many are you?’

‘Six. Please hurry.’

Attempts to run fresh air using a hose were frustrated by the high seas. Lieutenant Fitch tapped out a terse entreaty.

‘Hurry.’

Then, later,

‘Is there any hope?’

‘There is hope. Everything possible is being done.’

That night the S-8 began sending out a message, over and over again.

LIEUTENANT FITCH: YOUR WIFE AND

MOTHER CONSTANTLY PRAYING FOR YOU

It took until the following morning, sixty-three hours after the submarine had sunk, for Fitch to tap out his final reply.

‘I understand.’

A year later, when the vessel was salvaged, the divers ‘found a spectacle that moved them, hardy and inured as they are to horror, to deep emotion. Near the motors, arms clasped tightly about each other in protecting embrace, were two enlisted men, apparently “buddies”. The divers tried to send them up thus locked together, but the hatch was not wide enough and they had to be separated.’

If we are lucky, the way we leave this world will become the way we lived in it. According to Sylvia Plath’s Lady Lazarus – briefly brought back to life online in her creator’s flatly expressive voice, rocked shut like a seashell, unpeeling her skin in the same breath – dying is an art. Plath’s fatal, watery dreams merge in her ‘Ariel’, as her imagination flying over Dartmoor’s tors to evoke a distant glimpse, ‘a glitter of seas’ and a child’s cry, an echo of Icarus, the winged boy fallen from the sky.

Plath grew up on the southernmost tip of Boston’s North Shore, a site now overflown by planes taking off and landing at the international airport which has turned the streets she knew into potential runways. ‘My childhood landscape was not land but the end of land,’ she recalled, in the last piece of prose she ever wrote, now living in London, ‘– the cold, salt, running hills of the Atlantic. I sometimes think my vision of the sea is the clearest thing I own. I pick it up, exile that I am, like the purple “lucky stones” I used to collect with a white ring all the way round, or the shell of a blue mussel with its rainbowy angel’s fingernail interior; and in one wash of memory the colours deepen and gleam, the early world draws breath.’ She remembered other debris, too, ‘sea-beaten’ nuggets of brown and green glass – ‘blue and red ones rare: the lanterns of shattered ships?’ And she recalled her mother’s stories of wrecks picked over by townspeople on the shore like an open market, ‘but never, that she could remember, a drowned sailor’.

As a child, Sylvia had crawled into the water – ‘Would my infant gills have taken over, the salt in my blood?’ – and later taught herself to swim. She believed in mermaids more than in God, and saw the sea as ‘some huge, radiant animal’. At six years old, she and her younger brother watched a hurricane sweep over Cape Cod Bay, ‘a monstrous specialty, a leviathan. Our world might be eaten, blown to bits. We wanted to be in it.’ The storm rocked their house, howling outside the black window in which her face was reflected like a moth trying to get in. The sea was her past, sealed off like a ship or a god in a bottle, ‘beautiful, inaccessible, obsolete, a fine, white flying myth’. But it was her now, too, and it seethed through her poetry – ‘A far sea moves in my ear’ – sucking her body of blood till she was as white as a pearl.

As a teenager Sylvia returned to Cape Cod, which she had known all her life. She was the same age as Pat, swimming and sunbathing, modelling herself on Marilyn Monroe with her bright white bikini, her beach tan and her sun-bleached hair. She worked here in the summer as a mother’s helper, looking out longingly from her duties to the ‘blue salt ocean’. It promised all the ecstasy of expectation. But it was disturbing, too. Plath was already experiencing deep bouts of doubt and depression. In the summer of ’fifty-two she read To the Lighthouse, underlining the lines ‘Of such moments … the thing is made that remains for ever after’; in her beach bag was a copy of Orlando. The following summer of ’fifty-three, she swam out into the sea, and kept on swimming, trying to emulate her heroine, ‘Only I couldn’t drown.’ Two days later, and two days after that, she attempted again, and again, to take her own life.

Her mother tried to send Sylvia to a friend in Provincetown to recover. This place might have healed her. Instead she was admitted to an asylum where she felt she had been put under a glass bell. Electrodes were attached to her temples and dials turned on a console that resembled the equipment my father used to test the resistance of electrical cables. Instead of testifying to her resistance, they systematically attacked her memory, the most precious thing she possessed: the means of her imagination.

In 1957 Plath came back to Cape Cod with Ted Hughes. The newly-weds spent a seven-week summer here, a delayed honeymoon. It was a heady time. They stayed in a cottage at Eastham, down the coast from Provincetown. Sylvia introduced her lover to the beaches. Her favourite, at Nauset, named after the original inhabitants, was a bike ride away, and in her journal she recorded the rhythm of their lives, ‘write, read, swim, sun’, as if it would never end.

Walking between Nauset and Coast Guard Lights, the shore where the Pilgrims first sighted land, the pair found a sandbar, shallow and smooth. Floating with her hands and feet bobbing like corks, her wet hair trailing as if to trap the fish, Plath felt a sense of power and glory. The possibility of a new life lay ahead; the elemental flux refixed her; she was recalibrated to the ocean. The pair were caught in the ‘great salt tides of the Atlantic’; for Plath, marriage had set ‘the sea of my life steady’. To enshrine it, the two poets recorded the shore. She saw fiddler crabs in a dried pool at low tide, scuttling to dig themselves into the sand with their one gigantic claw; they were denizens of a ‘weird, other world’. He would recall the ‘pre-Adamite horse-shoe crabs in the shallows’, their ‘honey-pale carapaces’ and the ‘wild, original greenery of America’. They were post-war, modern people; they could fly over the ocean that had defied Shakespeare, Keats and Woolf. Here they found the oldness of a new world that Hughes had imagined before he’d ever seen it, defined by the ocean and ‘the whaled monstered sea-bottom’. His words echoed Eliot’s, who’d sailed here as a young man and found ‘hints of earlier and other creation: | The starfish, the horseshoe crab, the whale’s backbone’.

While her husband thought of the men who drowned out there, ‘Where darkness on Time | Begets pearl, monster and anemone’, Sylvia was reading Woolf again. She finished The Waves, disturbed by its ‘endless sun, waves, birds, and strange unevenness’. She felt Woolf’s writing made hers possible: ‘I shall go better than she.’ The crystalline memory of that time would be set in the shadows of the future. Hidden in the sardonic snarls of ‘Daddy’ – partly written about her father, whom Plath saw as a dark Prospero, and partly about her partner, who, like everyone else, would leave her in the end – is a sudden shining invocation of happiness: the sight of a seal, ‘a head in the freakish Atlantic | Where it pours bean green over blue | In the waters off beautiful Nauset’. These lines would come to haunt Hughes, who, like Plath, believed in signs and wonders, and who, years later, recalled that same shore descried in Sylvia’s ‘seer’s vision-stone’ – one of the white-ringed purple stones she picked up from the beach. Through it he saw her brown shoulders, now in a black bathing suit, secure on her childhood’s shore. On the beach, everyone is immortal.

But Plath knew none of this was real. She was engulfed by the tyrannical beauty of this place. ‘I’d rather not live in this gift luxury of the Cape, with the beach & the sun always calling … I need to end this horror: the horror of being talented and having no recent work I’m proud of, or even have to show.’ The world was speeding past. As they trudged under the hot sun along the sandy roadside of Route 6, where the pines grew short and looked as young and as old as the country itself, ‘deathly pink, yellow and pistachio coloured cars’ shot by, ‘killer instruments from the mechanical tempo of another planet’. The pair were relieved to reach the beach, where the red-and-white Nauset Light surveyed waves five miles long.

Plath left the sea for Smith College in Massachusetts, where she was taught Melville by Newton Arvin, known as ‘the Scarlet Professor’ (and was also lover to Truman Capote). She lived with Hughes in the nearby town; someone in Provincetown who’d been to the same college told me that his landlady had complained about being unable to get rid of the smell of perfume which her former tenant, a poet, had spilled on her desk. Plath was rereading Moby-Dick and finding solace in it, ‘whelmed and wondrous at the swimming Biblical & craggy Shakespearean cadences, the rich & lustrous & fragrant recreation of spermaceti, ambergris – miracle, marvel, the ton-thunderous leviathan’. She even imagined herself, ‘safe, coward I am’, aboard a whale ship ‘through the process of turning a monster to light and heat’.

Four years later in her London flat, in the winter of 1962 – the coldest for two hundred years, when the capital lay covered in snow and ice and she was reduced to wrapping herself in her coat and walking to the telephone box to plead with her husband to come back or to tell him to leave the country forever – Plath wrote a radio talk for the BBC. It was entitled ‘Ocean 1212-W’, after her grandmother’s telephone number on Boston’s North Shore. In it, she recalled the hurricane which had turned a childhood afternoon sulphurous and dark. ‘My final memory of the sea is of violence,’ she wrote, ‘– a still, yellow day in 1939, the sea molten, steely-slick, heaving at its leash like a broody animal, evil violence in its eye.’

She would never record the broadcast. Two days later, with the snow still lying on the city’s streets and her children in their beds, she carefully sealed the kitchen with wet towels, turned on the gas, and put her head in the oven.

On the winter shore, where the sea rises higher than my head, Mary and I scramble down a great sandy scree. All around us purple and green stones stand proud where the air has scoured around them, leaving them balanced on gritty pedestals like miniature megaliths. Others have tumbled down the cliff, leaving a drunken trail behind them. We wonder if they continue to roll while we’re not looking, only stopping when we stare at them. Clumps of compass grass, true to their name, draw circles around themselves as they whip about. Their stalks are brown and dead, all colour drained away by the dunes. But they’ve been resurrected by the wind.

We associate the beach with life, with warmth and the sun; not this numbing down, this low-season, reiterated death. At Race Point, the old lifesaving station stands empty; there’d be no handsome New Englander ready to throw me a lifebuoy if the ocean or my heart decided this was my last swim. The New York Times of 23 August 1883 recommends this shore to ‘those looking for good surf-bathing’, so empty even on a summer’s day that ‘if one wishes to go in in his bare pelt he may do so without the fear of shocking propriety’. Although it is January and the air temperature is about to fall to minus twenty, I duly heed the Times’s advice.

You have to take your chances with this ocean, roaring, rising high, utterly elemental and unharnessed, more like a mountain range than water. I wait for my moment, trying to judge when to get in, if I should get in at all. The water is warm compared to the air. And just as the waves roll me around, like stones in a barrel, I feel abraded by the winter, made raw, my bones exposed by the cold, both withdrawn and peeled back by it, as if I took off my skin too when I skinny dip. The cold removes sensation then restores it. The hardness of winter is an absolute in an equivocal world.

Each day seems colder than the last. The black ducks and eiders come into shore, seeking the respite of the sand. But the buffleheads, the smallest ducks – so sharply marked in stark black and white that they look more like feathered orca than the buffalo they supposedly resemble – stay out, diving fast and brave beneath the surface. It is strange, this comfort birds offer us, considering the discomfort they seem to suffer. Polar animals occasionally arrive here: a beluga whale once nosed around the moored boats, and a bowhead whale has appeared in recent years, caught up with its right whale cousins, its slow smooth bulk bringing an Arctic chill to the bay.

The North does not feel far away: in Pat’s paintings of frozen seas, echoes of the icy waters in which her great-grandparents perished, or in the thick snow through which I wade to get into the water after driving back from New Bedford with Dennis in a blizzard whose swirling blinding flurries rouse like ice monsters, turning the Cape landscape into the Russian steppes. A few doors down from here is the home of the polar explorer Donald MacMillan. His wooden house stands over the beach as if it had arrived here on a floe, stranded like all those fatal ships – Resolute, Erebus, Endurance. Surrounded by a white paling fence, its lawn could have been a corral for the polar bear whose stuffed and yellowing remains rear over visitors to the town museum and in whose skin MacMillan might be hidden, like some Inuit shaman.

At MacMillan Wharf, named in his honour, the trawler Tom Slaughter out of Gloucester has come into the harbour, seeking shelter; the young bearded crew might have been fishing here for a hundred years. Dovekies – little auks, their wings whirring like clockwork toys, wound up by their economic binomial, Alle alle – fly in, too. Named after the Swedish diminutive for dove, they’re also known as ice birds. Out in the open ocean they assemble in their millions, flying through the water on their wings to feed. They’re seldom seen this close to shore, these brave, stubby birds; some storm far out at sea has driven them in, along with all the others. In Charles Kingsley’s The Water-Babies, young Tom, become amphibious, goes north in search of Mother Cary, passing tens of thousands of birds, ‘blackening all the air; swans and brant geese, harlequins and eiders, harelds and garganets, smews and gooseanders, divers and loons, grebes and dovekies, auks and razorbills, gannets and petrels, skuas and terns, with gulls beyond all naming and numbering’, ending up in the frozen waters ‘where the good whales lay, the happy sleepy beasts, still upon the oily sea’.

Everything has been slowed down; a slow pace for a slow place. A Provincetowner lends me Sten Nadolny’s The Discovery of Slowness, a retelling of the life of Sir John Franklin, would-be discoverer of the North-West Passage. Nadolny’s prose itself slows the reader as he lays out Franklin’s story: his slowness to respond to his teachers in his Lincolnshire school; his slowness to draw fire on the enemy at the Battle of Copenhagen, where Nelson appears, never quite appearing; his slowness to stop strangling a Danish soldier with his bare hands; his slowness to respond to a man overboard when sailing with his uncle, Matthew Flinders, to Terra Australis, where Franklin would become lieutenant-governor of Van Diemen’s Land; the way he leaves a pause before he answers, the consideration he gives to what he is about to say, the manner in which he seems to militate against an accelerating century. All these happen at a glacial pace. Slowly moving through history, slowly moving across the ice, eyes protected against snow blindness by wooden spectacles, the sea slows him down too, as well as providing him with a kind of certainty. ‘As long as there was the sea, the world was not wretched.’

But most of all, the explorer’s slowness slows him to his ending on Erebus – named after the god of darkness – out on the slow-moving, ever-reforming ice which, it seemed then, would never end, and where he succumbs to a stroke, leaving his starving men to eat each other. To the native hunters who saw them, the lost, bedraggled adventurers were dead men walking.

In the dark morning I pace the deck, waiting for the light and the tide to arrive. It is shocking when the sun comes up, lifting over the sea, as if I’d forgotten it was there.

As I swim off Pat’s bulwark, there’s a commotion on the sea wall. Running along its concrete edge in front of the Icehouse, a fish storage block turned into apartments, are a pair of foxes. They’re in peak condition, red and ginger and grey, brushes held out proudly as though they’d come straight from the hairdresser’s. ‘Would you like some product on that?’ They follow one another nose to tail, resplendent in their ordinary otherness, calmly trotting over the deck before vanishing down the alley.

Pat calls me in after swimming to warm myself by the stove. I crouch over it, dripping, clad in a towel and my trunks. Its cast iron is piled with bricks to radiate its heat, creating a votive altar on which little metal figures perch as household gods: a long-eared African running dog; a bronze rat, wired to a whale vertebra; and smallest of all, a tiny cold-painted pale-green monkey with wire-thin curling tail. The stacking and burning of wood from the cords piled outside; the lichen-covered logs scattered with frozen cats’ turds; the loading into the barrow and the trundling to Pat’s door (Caliban would complain that there’s wood enough within) – all this proposes a primal exchange: trees for heat; my body for the sea.

Pat stokes the fire with a poker, the incandescence catching the light in her eyes and her hair. Lulled by the dumb cold outside and the dry warmth within, we talk about her past: how her mother left her father when Pat was three years old; how her uncle, a naval commander, arrived on his aircraft carrier in New York harbour, and how she climbed right up the rigging. She still remembers that feat: the fourteen-year-old hoyden caring nothing for convention, running up the ropes as if to spy out her future over Manhattan and the sea beyond. She calls her father Daddy and repeats his full name, Ernald Wilbraham Arthur Richardson, as if to draw him near.

All too soon the afternoon darkens into night and the windows, which briefly burst into life with a final flare of the setting sun, turn into black screens. ‘What a fine frosty night,’ says Ishmael; ‘how Orion glitters; what northern lights! Let them talk of their oriental summer climes of everlasting conservatories; give me the privilege of making my own summer with my own coals.’