In July 1910, seven decades after Elizabeth Barrett Browning had arrived there and eighteen years after Oscar Wilde had left, a teenaged boy from Shrewsbury spent a summer holiday with his uncle and aunt in Torquay. He knew this place and loved it, particularly for the bathing. That year, however, there was a new excitement to his stay. Two hundred vessels of the Royal Navy’s Home Fleet had gathered in Torbay to mark the accession of the new king, George V. Yet the spectacle that day was not confined to the sea. For the first time, boy and king would see an aeroplane soaring into the skies. It seemed like a good omen for a new reign; an intimation of glamour and technology. But it also promised another kind of future, one to which the young man – Wilfred Owen – would bear witness.

Like Elizabeth, Wilfred had come to join his relatives in the town. But unlike her uncle and aunt, living in a grand house on the hill, John and Ann Taylor lived at 264 Union Street in the commercial centre, between a bank and a pub. The wealthy winter visitors to Torquay were now giving way to more ordinary holidaymakers, and the ground floor of the Taylors’ house was a shop where they sold books, magazines and stationery. The building is still there: its wide, double-fronted bay windows, which once showed its wares, now display bridal gowns. Wilfred loved the shop; it felt special, the way things do on holiday. Passing the local newspaper office, he imagined a career as a journalist. He thought about the life of a poet, too, although that seemed even more fantastical. He had discovered that Christabel Coleridge, granddaughter of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, lived close by, and one morning he arrived unannounced on her doorstep. Miss Coleridge and her brother Ernest obliged by signing his edition of their ancestor’s poems. Other poets he revered had visited the area too. In ‘the azure time of June’ of 1816, Percy and Mary had spent a second, secret honeymoon in Torquay in ‘one soul of interwoven flame’. And two years later, a year after his visit to Southampton and the Isle of Wight, John Keats had stayed for two rather rainier months at neighbouring Teignmouth.

Wilfred felt connected to these poets; they spoke to him over time. Later, he would take the train to Teignmouth, where high tides and winter storms often threatened to cut off Brunel’s coastal railway; enveloped in cloud, Keats said Devon was so wet that it was amphibious. He had come here to look after his brother Tom, who was mortally sick with consumption, the same disease that would kill himself. But it was also here, by the sea, that he completed Endymion, just as he had begun it by the sea, on the Isle of Wight (and described the whole process as leaping into the ocean to become more aware of his surroundings). Staring into the windows of the house where his hero had stayed, Owen alarmed the inhabitants, so he walked down to the shore, where Keats had seen ‘the wide sea did weave | An untumultuous fringe of silver foam | Along the flat, brown sand | I was at home, | And should have been most happy – but I saw | Too far into the sea …’

Back in Torquay Wilfred wrote a sonnet to his patron saint: ‘Eternally may sad waves wail his death.’ He told his mother, Susan, that he was ‘in love with a youth and a dead ’un’; and when he read William Michael Rossetti’s biography of the poet, he felt that his hand had been guided ‘right into the wound … I touched, for one moment the incandescent Heart of Keats.’ (In a world in which words could pass on as relics, Rossetti himself had befriended the elderly Trelawny, who gave him a blackened fragment of Shelley’s skull taken from the funeral pyre.) But for Wilfred, the worship of dead poets was caught up with the sea and the life it offered; the water was the overwhelming reason to love Torquay on this, his third visit there, now with his brother Harold, four years his junior. ‘The whole day … centres around the bathing, the most enjoyable we have ever had, I think,’ Wilfred told his mother, adding, in his sweetly self-important way, ‘It is one of those rare cases where the actuality exceeds, does not fall short of, the expectation.’

He may have been born in landlocked Shropshire, but Wilfred had a strange connection to the sea. His father, Tom, would pretend to be a sailor – although his maritime experience amounted to little more than having once sailed to Bombay as a young man. He now worked as a railway clerk, but in his spare time Tom Owen assumed the stance of a captain, dressing up in a nautical, Gilbert-and-Sullivan manner on his visits to Liverpool docks, where he acted as a volunteer for the Missionary Society. One day he invited four Lascars home to tea; Harold remembered eight bare Indian feet appearing under the family table.

Mourning his imaginary career, Tom Owen invested his hopes in his eldest son; he planned a life at sea for Wilfred from the first.

An early family photograph depicts Tom in a sort of seaman’s outfit, with a straw hat and wide white trousers. Balancing the infant Wilfred on his shoulder like a kitbag, he poses like an Edwardian idea of a sailor. Harold – who really would go to sea – thought their father looked like Robert Louis Stevenson, with his long, handsome moustache. In another photograph, young Wilfred, dressed in his own white sailor’s suit, holds a toy yacht made for him by his father. And later, a little older, posed on a swing in navy blue, he seems already set for the sea, looking off to his own horizon.

At the age of six, Wilfred was taught to swim by his father on evening visits to the local public baths, where he displayed ‘a lithe aptitude for the water’. On holiday, Tom Owen insisted that his children should swim in the sea every day, whether the sun shone or not. It was a ritual for him, and became so for his eldest son.

At Tramore, near Waterford in Ireland, where many ships had been wrecked, Tom took the boys into a rough sea. Told by local fishermen to return to the shore, he defied them, recklessly diving into the waves and spouting through his moustache looking like a walrus. Later, the Owens caught a large dogfish which they stored overnight in a shed, only for Wilfred and Harold to find it rearing up in a corner on its tail, its mouth gasping and white; they thought it was walking like a man. The resurrected fish was duly released back to the sea, where it continued to be seen, swimming in the shallows. In another eerie incident, the family went for a walk down a dark, tree-shaded lane. A large animal seemed to be moving in the branches above them. At the end of the path a lake appeared like a mirage, and out of the darkness stepped a threatening figure that confronted their father while the children looked on, shaking with fear. None of this was explained, although the fisherman and his wife in whose cottage they were staying looked at each other strangely and asked the Owens not to tell anyone about what had happened.

In Harold’s remembering it seemed that the family were collectively haunted, as families can be. Wilfred embodied that mystery; they all felt he was in some way different, with his solemn gravity but sometimes wildly high spirits. Dark-haired and dark-eyed, he was proud of his Celtic blood, and had an animal love of loneliness. They called him the old wolf; he might as easily have been a selkie.

Everywhere he could, he swam in the sea. ‘We bathe here every day,’ Wilfred had written from Cornwall in the summer of 1906. Now a teenager, the water released a new energy in him. Staying in Bournemouth, he told his mother, ‘I have been so often at the Sea Side in Day Dreams of late.’ Those dreams took shape in a long and enthusiastic poem based on Hans Christian Andersen’s ‘The Little Mermaid’, in which the heroine gives up the sea for the land so that she can meet a young prince; Andersen’s story was a cipher, as Elspeth Probyn would write, ‘for an impossible love’. Wilfred was influenced by Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner and by Turner, whose paintings he had recently discovered. In lines neatly written out in his exercise book in his open, fair hand, he imagines the ‘exceeding deep’ beyond the ‘sea-bird’s view’, and ‘the tireless glee | Of waggish dolphins turning somersault | And whales a-snorting fountains angrily’. Such scenes make me wonder if Wilfred had seen cetaceans as a child, but his animals seem to have surfaced from Endymion, whose ‘gulphing’ whales and ‘Ionian shoals of dolphins’ would be familiar to Orlando and Oscar, too.

That summer in Torquay, Wilfred and Harold found a secluded cove, away from the other beaches with their deckchairs and families staking claim on their bit of England in the sand. To get there the boys walked up the hill, past the house from which Elizabeth had looked out to sea, and over the headland to Meadfoot. Here Charles Darwin had convalesced; his neighbour was Angela Burdett-Coutts, the richest woman in England; another villa was owned by the Romanoffs. The area’s well-to-do air appealed to the snob in Wilfred. But beneath the cliffs was the winding darkness of Kents Cavern, where three species of humans had lived; its prehistory appealed to the archaeologist in him. The beach was clean and wide, with flat pebbles veined with quartz; it looked out to a jagged shard named Shag Rock after its sentinel birds and driven at an angle into the sea, like something that had fallen from the sky.

One morning after swimming, Wilfred proposed an impromptu investigation of the geology of the cliff. As the brothers busied themselves with their excavations, as if looking for a psammead, they noticed two boys and a girl also digging about the rocks. Wilfred found the newcomers interesting – especially one of the boys, Russell Story Tarr. His father was Ralph Stockman Tarr, from Gloucester, Massachusetts; his ancestors included mariners and fish-oil merchants and women accused of witchcraft. A renowned geologist, student of marine zoology, collector of meteorites and Arctic explorer, Ralph Tarr was about to leave for Spitzbergen to investigate the physical properties of ice. The Tarrs were rich, evidently: Russell and his sister Catherine were staying with their parents at the grand Osborne Hotel, overlooking the beach.

Russell, bespectacled and about to go up to Harvard, was the personification of a new world. He and Owen were the same age, seventeen, and shared a love of geology; more importantly, Wilfred admired Russell’s prowess in the water. ‘This American boy is a splendid swimmer,’ he told his father. Russell would dive from a moored raft in the bay, disappearing for a dangerously long time, to emerge exhausted but clutching two handfuls of pebbles to prove how deep he had been. Wilfred and Harold tried to emulate him, but came nowhere near to doing so. Besotted by their new friend, the brothers would make the daily trek to Meadfoot to join Russell on the beach. In turn, the young American invited them to spend the following summer in New England. He couldn’t understand why the Owens were unable to accept.

As the summer stretched ahead, Wilfred and Harold were left to their own devices and diversions – among them one of the most splendid spectacles at sea that the country had ever seen, as the new king-emperor arrived to review his fleet. But the focus that day subtly shifted, from the monarch to another figure.

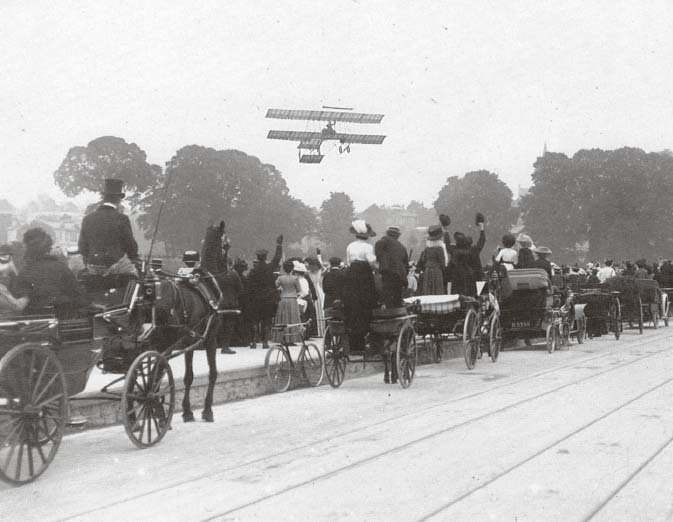

Claude Grahame-White was Britain’s most celebrated and handsome aviator, a former car salesman whose aeronautical outfit consisted of a three-piece knickerbocker tweed suit, cap and tie, sportily set off with a cigarette dangling nonchalantly from the corner of his mouth. His aeroplane looked more like a mechanical bird than a flying machine: a fragile thing of wood struts, doped linen and animal glue, yellow-skinned and thin-boned, held together by faith as much as by technology. Its appearance, one thousand feet over Torbay, was akin to the sighting of a UFO; the first time most of the crowd – which had been, up until that moment, an Edwardian assembly with straw boaters and picture hats and long skirts, craning their necks to watch the plane swoop over the bay – had ever seen anything other than a seagull in the air. Suddenly, they were modern. They were looking at the future. A man, flying.

The Farman III biplane took off from the beach-side field in front of Torre Abbey, flying over its gothic arches and the Georgian mansion where Nelson had once dined. Biplanes generally flew at dusk, when the day’s winds had abated. Grahame-White was borne up on a thermal, rising on the summer heat that had kept children paddling in the water all day. The aircraft glowed as sparks from its engine lit its linen wings like a Chinese lantern. Suffused with the colours of twilight, the scene might have been painted by John Singer Sargent.

Yet the pilot’s intent was anything but glamorous. The next day, on his second launch, he flew in the cold light of dawn. It was a foggy morning, and it seemed the review would have to be called off. But then the mist lifted to reveal eight columns of ships of the Royal Navy, sea-going enforcers of the greatest empire the world had ever seen. It was a unique assembly, an absolute demonstration of imperial power and industrial mastery of the sea: one hundred million pounds’ worth of weaponry. These ‘engines of war’ were an index of dominion, sweeping over heroes and victories and kings and colonies and out to the stars themselves: St Vincent, Collingwood, Lord Nelson and Temeraire; Edward VII, Hibernia, Africa and New Zealand; Dominion, Commonwealth, Hindustan and Britannia; Vanguard, Superb, Bellerophon and Jupiter. Not even the underwater world went unpatrolled. Six submarines – led by the leviathanic D1, built in utmost secrecy in Scotland and showing ‘like a salmon among minnows’ in the mechanical shoal – rounded Berry Head to the surprise of its dolphins and porpoises, and slid into place in the bay.

George V’s ascent to the throne, the reassurance of the same, seemed a bulwark against the changes of the new century. But that summer, as Wilfred and Harold swam and children played on the beach, Britain was filled with war games. Territorial troops were training on Salisbury Plain, and in Kent soldiers practised with machine guns on night operations. In Wales, the Royal Welch Fusiliers were faced with the prospect that a revolt in Ireland had been followed by a landing of forces north of Aberystwyth. And in a vast exercise carried out on the Firth of Forth, hundreds of troops, including the Cyclist Battalion of the Royal Scots, fought an imagined invasion landing at Dunbar, intent on marching on Edinburgh. Every shore of the kingdom seemed threatened; the country was preparing for attack from every direction, even from under the sea.

The militarised new monarch – ‘it must not be forgotten … that the King himself has handled a torpedo-boat, voyaged in a submarine, and commanded various classes of vessels from a gunboat to a big cruiser’ – watched from the armipotent battleship Dreadnought, the incarnation of imperial might (for all that a few months before, Virginia Woolf, along with five of her Bloomsbury male friends, two of whom were lovers, had conducted their own stunt, boarding the ship in Weymouth wearing costumes and blacked-up faces, pretending to be a royal delegation from Abyssinia).

As the monarch peered up through his telescope, the biplane passed directly overhead. To The Times, it was an uplifting sight; Grahame-White was exhibiting a new kind of art. ‘He made a particularly pretty flight, rising easily to about 1,500ft … then gliding round to a lower level to give the King an opportunity of seeing him more closely as he flew over the Dreadnought.’

The reporter was caught up in wonder like the rest of the crowd; this was aerial choreography to rival any Russian ballet. ‘All his gyrations and movements were made with that ease and smoothness for which he is noted, and his swoop to the landing-place was particularly workmanlike and beautiful.’ And as he rose over the trees under which their carriages were gathered, the crowd looked up as one in wonder. Their horses stood straight ahead, eyes blinded by leather blinkers.

At five o’clock that afternoon the aviator made his third flight. The fog was thickening, putting an end to the naval exercises, and the ships were coming in. As he soared over Dreadnought once more, Grahame-White dipped his wings and saluted his monarch.

The king waved his telescope-sceptre from the deck of the world’s most mighty ship. He did not realise what had changed in that instant.

The pilot had proved his point. None of the navy’s guns, able to quell rebellion and enforce diplomacy in every ocean, could swivel upwards and – had Grahame-White been an enemy – take him down. This Icarus in a tweed suit, borne aloft by linen wings and perched on what was little better than a kite with a car engine, was an augury of the time when such frail contraptions would become terrible firebirds, dealing not delight but death from above. As any classically-educated observer in the crowd might have noted, the word augury referred to the Roman belief in determining the future from a bird in flight, and shared the same root as avian and aviator.

That night, Wilfred and Harold stayed out on the cliffs until midnight. Looking down on the promenade strung with lights and dotted with palm-like cordylines, they pretended Torquay was some city in the tropics, shimmering under the dark-blue sky. Out at sea, the fleet was also lit up, and every now and again a ship would send up a rocket, its trail reflected in the black waters of the bay like a falling star.

The following spring, Wilfred returned to Torquay, alone. He missed Russell, who was now at Harvard, and in solitary moments the young poet sat on the rocks at Meadfoot, reading a French book he’d bought, filled to overwhelming with the sea. As a would-be university scholar himself, Wilfred translated a passage from Alphonse Daudet for his mother’s benefit: ‘You know, don’t you, this lovely intoxication of the soul? You are not thinking, you are not dreaming either. All your being escapes you, flies off, is scattered. You are the plunging wave, the dust of foam which floats in the sun between two waves … everything but yourself.’

‘Well, I was reading the book at Meadfoot the other afternoon,’ said Wilfred, as he broke off from his reverie, ‘when who should I see but the boy-youth whom we met with Russell Tarr, and who played croquet with us on the lawn, as Harold will …’

But the rest of the letter is missing, as are Wilfred’s other letters about Russell, censored by his brother in order to preserve his brother’s reputation – at least, as he saw it. Harold blocked Wilfred’s words with black ink; often he cut out paragraphs or removed entire pages. What was left made a mystery of what might have been banal, or perhaps not so. That not-knowing, the withdrawal of permission, is physical, like someone holding their hand in front of your face. He was doing to Owen’s letters what the sea had done to Shelley’s notebook; only instead of the water washing out the words, thick squid-black ink covered their traces. The result was quite contrary to Harold’s intent. He only made the ordinary more extraordinary.

It wasn’t the job Wilfred had imagined back in Torquay, but it would do for now. He was hurtling through the country lanes of Berkshire on his magical Sturmey-Archer three-speed bike, attending to his duties as assistant to the vicar of Dunsden. Cycling, like swimming, was a release; it took him into the natural world. He was a keen bird-watcher, and admired swallows so much that his family called them Wilfred’s swallows. Such fast birds fascinated him, built only for the air, hardly ever touching the ground, yet travelling from one hemisphere to the other. He had recently written a Keatsian ode to the swift, ‘Airily sweeping and swinging, | Quivering unstable’, and as he cycled below, their wings carved their own curves into the sky: ‘If my soul flew with thy assurance, | What Fields, what skies to scour! what Seas to brave!’

Despite its sententious reverend and the deadening sound of the vicarage clock ticking away the afternoon, Wilfred liked his new post. Dunsden sounded dull, but it lay close to the Thames; he was excited to learn that Shelley had lived in a cottage by the river in Marlow, where he’d erected an altar to Pan in the woods.

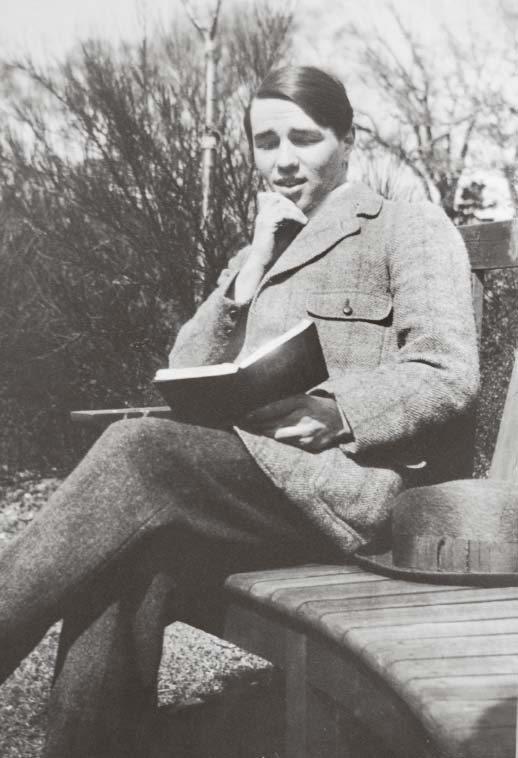

A photograph of Owen in the vicarage garden shows a typical teenager. He sits with his legs crossed and his body at an angle; a short, neat young man, just five foot five.

Perhaps it’s Sunday, the dullest, freest day of the week. He’s wearing a checked Norfolk jacket, flannel trousers, a Homburg hat by his side. His hair is side-parted. There’s a critical look on his unformed face as he reads aloud from a book held in one hand, the other curled under his chin. He may be serious; he may not. I imagine him arguing passionately from under that floppy hair and furrowed brow, all taut with complexities, even as you can hear him complaining about being told to tidy up his room when he has more important work of his own to do.

He had just returned from the Lake District, where he’d spent a week at an open-air Evangelical gathering, his generation’s version of a music festival. He was devout despite his doubts, and in his letters – he would write five hundred to his mother during his lifetime – his voice comes alive, funny and questioning and energetic; so many words, as if he were cramming them all in. At this field camp, with its endless hymns and sermons, he’d slept in a smelly tent and sung along with all the other young men, finding only one, a mining lad, interesting. When he took his shirt off, the boy’s back showed the scars of his subterranean work; to Wilfred, he seemed somehow angelic, ‘tho’ pricked with piercing pain’.

Escaping the camp’s holy orders, Wilfred swam in the nearby lake, and cycled forty miles in the pouring rain to Coniston to see Ruskin’s house, Brantwood, set over the slate-grey water. Ever the fan, Wilfred called on Ruskin’s secretary and biographer W.G.Collingwood, who lived nearby. I don’t know if he swam at Coniston too; I did, and found it fearful with the memory of Ruskin’s madness, imagining the critic-prophet watching the storm clouds of the nineteenth century from his gothic turret overlooking the lake. That night Wilfred rode back through the storm, ‘drunk on Ruskin’ and utopias and possibilities.

Now he was back in his routine, on his bike, making pastoral visits to elderly parishioners, delivering not food but comforting words from the sermons of Charles Spurgeon, ‘about human lives being as frail as flowers, as fleeting as meteors’. Of course he wanted to be a meteor too, ‘fast, eccentric, lone, | And lawless’. Astronomy fascinated him: that April he had witnessed the greatest solar eclipse for fifty years (for which Virginia Woolf had travelled to Yorkshire), and in an earlier letter he had sketched a new comet he’d seen in the night sky.

Wilfred rode on with his head full of all these things: with Keats and Shelley and Ruskin and shooting stars and comets and his own poems as he hurtled through the countryside, when suddenly his bike skidded and he slid violently to the ground.

The incident lasted barely ten seconds. Dazed and in shock, he managed to ride back to the vicarage, where the housekeeper took one look at his white face and the deep cuts on his hand and sent for the doctor. Wilfred started to lose consciousness.

‘Sudden twilight seemed to fall upon the world, an horror of great darkness closed around me.’ He heard the blood roaring in his ears, and ‘strange noises and a sensation of swimming under water’. Although he did not faint, he broke out in a cold sweat and, somewhat deliriously, found himself ‘gasping at a window, without quite knowing how I got there’. He went to look in the mirror, in which he admired his ‘really beautiful and romantic pallor’, and claimed, ‘I had a presentiment that something of note would happen shortly.’ Wilfred was all too sensitive to omens; around this time he made a note on one of his loose pages: ‘why have so many poets courted death?’ He was in love with death, as boys are. It was the biggest adventure.

A few days later, Wilfred resumed work on ‘The Little Mermaid’, now into its second exercise book. He sent his heroine diving to the sea floor to find ‘a marble statue, – some boy-king’s, | Or youthful hero’s’, whose cold face she kissed. The drowned image, out of Coleridge and Shakespeare, foresees her fatal meeting with her prince, for whom she forsakes the sea, her elegant tail bisecting into two painful legs, as if she were walking on knives, like Byron. The poem ends as she helplessly pursues the prince’s ship into a storm, ‘All ears | Hark to a grumbling in the heart of the seas.’

On the Friday after Harvest Festival, Wilfred got back on his bike and rode to his cousins’ house for a family reading of The Tempest. The play was a set text on his correspondence course in his attempt to get to university, and he had recently seen it performed in London. The elemental drama touched him with its strangeness; it spoke to the distance he felt between his art and his nature; between the future and the past, between what people expected and what he wanted to be. Later that year he went to see it in London for a second time, and from the train on the way back he saw a biplane ‘high in the Western sky’, so high he could not hear it. The machine, from Grahame-White’s new aerodrome at Hendon, was all the more impressive for its silence against the setting sun, held in the windless air.

In April 1913, worn down by his duties at Dunsden, Wilfred returned to Torquay to recuperate from congested lungs; the sea air would clear them, so he and his mother, who feared the first signs of consumption, hoped. He found the resort a changed place. His uncle had died, and his aunt had moved to a smaller house. Wilfred revisited Teignmouth, and both there and at Babbacombe he observed that the swelling afternoon tide seemed to bring on the rain, which his scientific mind sought to explain: ‘the rise of such a vast surface of water … compresses the Air above to a greater density’. But as the clouds lifted, so did his depression about the dead end his life had reached, having failed to get into university. The ‘verray’ blue sea worked its magic – although, as he told his mother, there were three battleships in the bay, closer to shore than he had ever seen. ‘How melancholy-happy I was,’ he wrote, quoting Keats, his consumptive hero, ‘where the wide sea did weave.’

Wilfred needed to escape, and the opportunity arrived: the offer of a job as a teacher in Bordeaux. As he crossed the Channel, the world suddenly opened up. He was no longer a boy from a backwater. He was a new European man. He grew a moustache and wore his hair fashionably slicked back and centre-parted, and acquired a tan which would stay with him for the rest of his life. He even fantasised about rebuilding his body with international parts, like a mail-order version of Mary Shelley’s Creature. He chose eyes from France, mouth from Italy, hair from Greece, chest from Sweden, legs (‘badly needed’) from France also, and shoulders from America, ‘of course’. At twenty-one, he placed great store in his use of the word ‘Beautiful’.

The reality was somewhat different. Wilfred suffered hypochondriacally, detailing to his mother every symptom, living on chocolate and raw eggs and bemoaning the fact that his old green suit was wearing out. (He favoured green: it was the aesthete’s colour, as sported by Wilde and his acolytes. Later, playing a dandy in an amateur drama at Craiglockhart, he’d ask his mother to send up his green suit, green shirts and green glass cufflinks for his ensemble.)

Wilfred had accepted a new post, as tutor to the Léger family: Charles Léger was the founder of the experimental Théâtre des Poètes, and impressed Wilfred because as a boy he’d met Mrs Browning, who had shown him particular kindness; Madame Léger, his young wife, Wilfred’s student, ran an interior-design company. They were staying at their summer house in the Pyrenees, a villa in the Belle Époque style on the outskirts of Bagnères. The town’s name meant baths, famed since Roman times for its healing waters. Lourdes was only a few miles away, with its own miraculous spring.

Wilfred was introduced to a southern life. Dressed in a consciously cosmopolitan manner in straw boater, bow tie and smart ankle boots at an open-air reading, he sat next to Madame Léger – who rather fancied him, he knew – as they listened to the poet Laurent Tailhade, who rather fancied him too. A decadent anarchist and opium addict, and friend of Verlaine and Mallarmé, Tailhade had declared a terrorist bomb in the French parliament to be a ‘beautiful gesture’, much as Karlheinz Stockhausen would call the attacks of 11 September 2001 a work of art, or as Turner had hired a boat to paint the Palace of Westminster while it burned to the ground in 1834. Tailhade still supported the anarchists even after he was injured by one of their bombs and lost the sight of one eye. Under his radical, pacifist influence Wilfred’s ideas changed. He too would find art in disaster.

From the Légers’ villa Wilfred would walk into the hills, where he discovered a mountain stream in which to swim. His hosts advised against it: too cold, not deep enough, people might be about. Wilfred dismissed these prissy reservations. Having found ‘an enchanting stretch of water in an alder-glade, I was not long in “getting in”. So now I go down every day, and I know, when I vaunt my coolness and freshness, the others would be green with envy, if they were not so infernally red with heat.’ He might have been Shelley dipping naked in a neoclassical landscape. But this was August 1914, and in Futurist-inflected pararhyme, Owen recorded that last summer more surely than if he’d photographed it.

Boys

Breaking the surface of the ebony pond.

Flashes

Of swimmers carving through the sparkling cold.

Fleshes

Gleaming wetness to the morning gold.

He knew what he was doing. He was becoming a modern artist, physically expressed in his body. Even here, in the soft light of southern France, the seismic shocks of the war that would transform him were felt as disturbances in the air. Women cried in the streets, and Wilfred looked to the mountains of Spain in the distance, wondering if he ought to take refuge there. The wounded were arriving from the front; he saw German prisoners of war kept in cages. ‘I like to think that this is the last War of the World!’ he told his younger brother Colin, as though sharing some science-fiction comic.

Charted in his letters, the slow, inevitable speed of Owen’s assumption into war is frightening and obvious, as if he were cycling into it. I look at his bookended dates and wish I could have written a different biography for him. Perhaps if he hadn’t written it all down, or if I hadn’t read it, it might not have happened. I might have seen him in the nineteen-seventies, an old man with a greying moustache on Meadfoot beach, looking out to sea, looking back into a past that never happened.

Giving up teaching, Wilfred returned to Bordeaux and became a perfume salesman – a somewhat decadent occupation in wartime, although Stephen Tennant would have approved – then returned to London, crossing a sea sown with mines, patrolled below by U-boats and threatened overhead by Zeppelins.

Yet even this close to the point of no return, he was torn between art and war. He walked through the East End and down to the river at Limehouse, a tidal place with its own secrets. He saw a ‘godlike youth … with blood-red lips’ whom he dared not approach, and who merged with a shadow he met on Shadwell Stair, its steps leading into the Pool of London. This boy’s eyes reflected ‘moons and lamps in the full Thames’, and this water – another kind of danger zone – mirrored Owen’s desires, ‘Like the sleepy tide upon the sands | To feel and follow a man’s delight’.

But such Wildean scenes had been banished by a strident new voice. Rupert Brooke’s sonnet saw the fighting as an antidote to ennui: ‘To turn, as swimmers into cleanness leaping, | Glad from a world grown old and cold and weary’. To Wilfred, a stark choice presented itself. ‘I have made soundings in deep waters,’ he told his mother, ‘and I have looked out from many observation-towers: and I found the deep waters terrible, and nearly lost my breath there.’

He took a headlong dive. Once his decision had been made, the transition was abrupt, and shocking. On 21 October 1915 Owen was sworn in at the headquarters of the Artists Rifles in Bloomsbury; given that he felt he was enlisting to defend poetry, his choice of recruitment station, in an area of modernist dissent inhabited by Woolf and her war-resisting peers, is ironic. Within weeks his body was subordinated and subsumed into the military machine at camps in Essex and Aldershot, far from Lake District evangelicals, and even further from elegant French villas and the proffered embraces of older women and one-eyed anarchist poets.

A photograph taken around this time, only recently discovered, shows Owen in an ill-fitting greatcoat, handed to him straight from the stores. Its thick, rough wool – more like a blanket – is pulled in at the waist by a webbing belt. It swamps his little body, hanging off his shoulders. But what surprises most is the smile on his face. If it weren’t for the rather tentative moustache, he’d look like a ten-year-old who’d just scored a goal. He grins from ear to ear, showing off his white teeth and his dimples. He looks like a boy you knew at school. He simply seems pleased to be a soldier.

By the summer of 1916, the transformation was complete. His fringe, which once fell carelessly over his broad forehead, was cropped (‘Note I wear my hair ½ in long now’), so brutally that his brother would seek to censor these images too. Harold was amazed when he called unexpectedly on Wilfred in his barracks that September to find him ‘clad in khaki slacks and nothing else’, his bare torso impressively developed, toughened by training during which, like other officers, he had grown an inch in height.

Owen the suburban boy had become a sophisticated officer, with offhand manners to match. He rose from his camp bed and dressed himself, assuming an elegant persona ordered from smart London shops. His Pope & Bradley tunic, waisted and epauletted, emphasised his new body; his torso was restrained by the Sam Browne belt slung across his chest, the leather lovingly buffed with a velvet shoe pad. His neatly parted, cropped hair was slick with brilliantine and groomed, like his clothes, with ivory-backed brushes from Swaine Adeney. The silkily knotted tie and collar-pin, the gleaming boots and riding crop – these were all part of a modern poet’s armour in time of war: close-fitting, tailored, belted, buttoned and buckled. He was laced and strapped and tied and bound by the state, right down to his putteed legs. It was as if Wilde had been sent to war rather than Oxford; the aesthete’s green had turned into military khaki, as though already muddied by the trenches. His fellow officers were ‘desperate nuts in dress: as befits our calling, and immemorial custom of all gallants’; their favourite ‘Flash’ was to sport a violet handkerchief trailing from their khaki pockets. Wilfred felt that was a bit too flash – and a dishonour to that noble colour, purple. Nevertheless, he doused his handkerchief in scent to stave off the stink of sick horses, much as a Regency dandy had recourse to his vinegrette in the odiferous streets of Piccadilly.

Photographed by his uncle that summer, his face is startlingly modern. He could be anything, but this is what he has decided to be, for this particular moment. He is boyishly tanned, gazing under his peaked cap through grey-brown eyes, faintly smiling under his ‘soldierly moustache’, knowing, as we all do at that age, that deep inside he was not really a part of this at all; that this was just another skin which would eventually be shed. ‘Outwardly I will conform,’ he told Harold, ‘my inward force will be the greater for it.’ Finally his name was in print, but not in the way he’d imagined –

W.E.S. Owen, CDT

– reduced to tiny initials in the gazette pages of The Times, signifying nothing more glorious than an assimilation into the system, along with column inches of other officers. Only when you see him next to those fellow officers – of the Fifth (Reserve) Battalion, under the pines of their Surrey campsite – do you realise how small he is, and how different, for all his efforts to look the same. He might be a particularly elegant Boy Scout. Yet he was now in charge of other men, younger and older than him. Power and duty became him. His instincts lay with the other ranks; his snobbish side allied with the officers: ‘I am marooned on a Crag of superiority in an ocean of soldiers.’ As a second lieutenant out training his platoon, he could break off from his duties on a hot summer’s afternoon by the side of a Hampshire lake – the order having been given for bathing to be allowed – and wander to a secluded cove where he found ‘a solitary, mysterious kind of boy’, the son of a Portuguese aristocrat, to swim with. He had a knack of finding such temporary companions. We forget, perhaps, what a charming man he was; or how sensually charged a war can be.

And Owen was a remarkably good soldier – good with his men, and an expert shot. Having proved that he could serve, that he had a place, he was determined to become an even more ambitious part of the war effort, in the Royal Flying Corps. ‘By Hermes I shall fly,’ he told his mother, turning himself into a young god. ‘I will yet swoop over Wrekin with the strength of a thousand Eagles … the pinion of Hermes, who is called Mercury, upon my cap. Then I will publish my ode on the Swift. If I fall, I shall fall mightily. I shall be with Perseus and Icarus, whom I loved; and not with Fritz, whom I do not hate. To battle with the Super-Zeppelin, when he comes, this would be chivalry more than Arthur dreamed of …’ Earlier, he had seen his first Zeppelin in the skies over his Essex camp, its body picked out in the searchlights. ‘The beast looked frightened somehow,’ he wrote, as he watched it nose about as if lost, only to vanish into a cloud which, he thought, was of its own making.

Wilfred was thinking of his favourite painting, Lament for Icarus, by Herbert James Draper, which was on display in the Tate Gallery, on the banks of the Thames. Draper liked to depict nude sirens decorously draped with seaweed in an imaginary sea; his Icarus, painted in 1898, sprawls on a rock in blue-green water, as if dragged out of Brueghel’s sea, or the Thames at Limehouse. The youth’s semi-naked body has been tanned by his close approach to the sun; he lies spreadeagled and folded in his huge but defunct wings, which Draper modelled on those of a bird of paradise.

But a painting in the Tate, no matter how heroic, was no substitute for the real thing: ‘Betimes I have a horrible great craving to behold the sea.’ Wilfred’s wish was granted that autumn, when he was sent to Southport for training – only to discover the tide there ran out so far over the wide flat sands – where half a century before Herman Melville had met Nathaniel Hawthorne and confessed his thoughts of self-destruction – that it was the ‘most unsatisfactory sea-side place in Europe’. Wilfred was under military manners but he could have still been a boy, writing home after leaving Torquay, ‘how I miss my morning bathe’. Within weeks he was on his way back to France; not as a young man in a dapper suit in pursuit of sensation, nor even a newly-fledged hero, but as a uniformed officer charged with the absolute implementation of violence. Those few miles of water between his island home and the embattled continent represented a new gulf. He already looked back to another life, ‘the days when my stars were bright from their creation by Pope & Bradley’. Inexorably, he was ordered to war, to experience its pity, and its pitilessness.

As he got nearer the front, Owen was physically assailed by the noise. It both repelled and drew him on. His duty was to minister to his men, much as he had ministered to the parish of Dunsden, ‘and this very day I knelt down with a candle and watched each man perform his anointment with Whale Oil’. Like a priest at the Mass of the Last Supper, he supervised them as they prepared for the flooded trenches by rubbing their bare feet with rendered-down blubber.

For these men, their future condition would be amphibian; this was a fearful morning bathe. Owen and his company were sent into the worst conditions on the Western Front, where the land had become ‘an octopus of sucking clay’, navigable only by aquatic duckboards. Bomb craters were bottomless lakes in which men drowned; others only managed to extract themselves by leaving their equipment and even their clothes behind – a weird, Stanley Spencer scene of resurrection, white bodies reborn out of primordial mud. These warriors were dressed ready to fish for some evil prey: Owen was ‘transformed now, wearing a steel helmet, buff jerkin of leather, rubber-waders up to the hips & gauntlets. But for the rifle, we are exactly like Cromwellian Troopers,’ lacking only the lobster-tailed helmets of the New Model Army. He could hardly breathe under his tin hat; when he took it off at night, he took in lungfuls of air, as if he’d been bolted into a brass diving helmet. He seemed to be walking on the sea bed. ‘In 2½ miles of trench which I waded yesterday there was not one inch of dry ground. There is a mean depth of 2 feet of water.’

It was a nightmarish version of those seaside days. He was weighed down; sinking, not swimming. Water had become protean and terrible, as it had for Elizabeth Barrett Browning and her memory of her drowned brother, evoked in Aurora Leigh: ‘When something floats up suddenly, out there, | Turns over … a dead face, known once alive –’. Arriving in the bombed-out village of Bouchoir, Wilfred found a copy of Mrs Browning’s collected poems, and in the battered book he underlined a passage from Aurora Leigh: ‘See the earth, | The body of our body, the green earth | Indubitably human, like this flesh.’ She was following him into the mire, picking her way through the devastation in her dark crinoline gown. Her words accompanied him as his mind wandered from the primordial mud to his internal ear, ‘having listened so long to her low, sighing voice (which can be heard often through the page,) and having seen her hair, not in a museum case, but palpably in visions …’

But this was no place for poets. This was nature suborned, perverted, and destroyed. Brooke’s clean swimmers wallowed in flooded trenches and their own dung. The countryside looked more like the blackened mud and debris left on the beach at low tide, with explosive shells instead of their marine equivalents and the buried dead constantly disinterred by each new wave of fighting. It was an inundated deathscape no silent film could record; although perhaps Shelley had foreseen this apocalypse, in which machines spewed Promethean fire and raptors pecked at heroes’ bones.

At one point Owen’s platoon took shelter in an empty German dugout, accessed by a tunnel which descended as deep as the height of a house. They remained for almost two days in this earthy chamber, like some prehistoric barrow, up to their knees in water which was rising ever further, while the enemy fired directly at them.

The men shook, spewed and shat themselves in fear. At one point the sentry Owen had posted at the top of the tunnel was hit, and came tumbling down the steps, ‘sploshing in the flood, deluging muck’. He was not dead, but he could not see.

‘O sir – my eyes, – I’m blind, – I’m blind, – I’m blind!’

Owen held a candle to his face, telling him that if he could see ‘the least blurred light’, he’d be all right. But he sobbed his reply, ‘I can’t.’ His ‘eyeballs, huge-bulged like squids’’, would haunt Owen for the rest of his life.

Everything was overcome. In his own desperation, Owen even considered allowing himself to succumb: ‘I nearly broke down and let myself drown in the water that was now slowly rising over my knees.’ Water had become a fetid medium in which war bred: as though Turner had reprised his Sunrise with Sea Monsters out of the Flanders mire, lashed to a lumbering tank – a land ship – while other armoured leviathans surfed over shell holes and sunken lanes like his scaly beasts, watched all the while by the helmeted enemy through submarine periscopes.

All the devils really were here. ‘Hideous landscapes, vile noises, foul language and nothing but foul, even from one’s own mouth (for all are devil ridden), everything unnatural, broken, blasted,’ Owen told his mother, invoking a seventh hell, scattered with the distorted bodies of the dead, ‘the most execrable sights on earth’.

Claude Grahame-White’s salesman’s prophecy had become a real war of the world, an alien invasion of machines that aped animals. Wasp-like aircraft buzzed overhead while whale-like Zeppelins, ominous five-hundred-foot-long, skin-covered shapes sailing over the German Ocean, dropped bombs on English resorts and even hovered over the shore where I swim. Britain was no longer safe as an island. The sea that surrounded it was now a conduit of disaster rather than trade or pleasure. It boiled and bled from below, as Virginia Woolf would write in To the Lighthouse. As the submarine peril increased, fear drove some to seek supernatural aid: the cost of a talismanic caul increased from one and six to three guineas for those who wished to protect their loved ones from drowning.

Meanwhile whales were mistaken for U-boats and blown up, or used as target practice, while their blubber was processed into nitroglycerine. The demand was sated by the slaughter of eighty thousand cetaceans, their bodies processed in remote whaling stations by other hip-booted men. Animals became by-products and victims of a great war in which as many horses died as men. It was a war for natural resources, the first war of the Anthropocene, an augury of extinction. In 1917 Siegfried Sassoon was appalled to discover that the real aim of the conflict was ‘essentially acquisitive, what we were fighting for was the Mesopotamian Oil Wells’. The machine was all-consuming, killing more whales and sinking more wells into oceans of oil, producing the raw material for more war. It was an inequitable, international exchange rate. In her diary, Woolf recorded that to kill one German at the Somme in 1916 cost Britain one thousand pounds; a year later, the price had risen to three thousand.

Sunk deep in those trenches, men donned aqualung-like masks against the waves of gas in ‘an ecstasy of fumbling’. One soldier unable to do so in time was watched by Owen: ‘Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light, | As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.’ The poet’s nerves, already raw, were brought to a state of exposure in those nine days at the front, each day worse than the last. As he slept on a railway embankment, a large shell landed barely two yards from his head, blowing him into the air, his body briefly leaving the earth. It was another transformation. A rebirth, of sorts.

At first it seemed he had only slight concussion; but a few days later he was observed, as his army file records, ‘to be shaky and tremulous, and his conduct and manner were peculiar, and his memory was confused’. He was suffering from shell-shock, brought on not by the explosion, but by the fact that he had lain in a pit for two days, sheltering under a sheet of corrugated iron next to his fellow officer, Second Lieutenant Gaukroger, who had been killed a week before and who now lay around him, in pieces.

Slowly, he was moved back to the sea. Étretat, a resort twenty miles north of Le Havre, was famous for its chalk cliffs, arches and stacks, much painted by the Impressionists. It too had become an anteroom of war, filled with khaki uniforms and materiel going one way, and doctors and nurses dealing with the results on the return journey. But it also represented the clear blue sea he loved. He was kept in a marquee on the lawn of a hospital run by the Americans – a reminder of his swimming friend Russell, himself now serving in the war, having found wings of his own in the intelligence department of the US Army, preparing maps for the 29th Engineers. It was as if Wilfred had finally been able to take up Tarr’s offer; like Woolf, he conjured up a continent he would never see.

‘I seem to be in America,’ he told his mother, ‘on this delicious Norman Coast,’ adding a little drawing of the Stars and Stripes to his picture postcard of Étretat’s cliffs. Warmed by the sunlight filtered through cream-coloured canvas, he could believe he had gone to heaven. ‘This is the kind of Paradise I am in at the present,’ he told Colin, his youngest brother. ‘The doctors, orderlies and sisters are all Americans, straight from N.York! I may get permission to go boating & even to bathe.’ He couldn’t quite comprehend that he would soon be back in England – ‘I shall believe it as soon as I find myself within swimming distance of the Suffolk Coast,’ he declared, as if he might flout all authority and swim back home. Instead, he contented himself with the prospect of the French beach: ‘If I go bathing this afternoon it will be to practise swimming in Channel waters.’ He was only a few miles from the shore where Mrs Browning had come to dip her body in salt water.

A few days later, Wilfred was taken back to England by converted West Indian liner – with the luxury of a cabin to himself – not to the Suffolk coast, but up the Solent to Netley’s vast military hospital. ‘We are on Southampton Water, pleasantly placed,’ he told his mother, ‘but not so lovely a coast as Etretat.’ The sea overcame words and what he had witnessed. ‘Nothing to write about now. I am in too receptive a mood to speak at all about the other side the seamy side of the Manche. I just wander about absorbing Hampshire.’ He felt a sense of disconnection, in his abrupt transition from the front and its deafening death cult to a semi-rural site with its main building an endless brick terrace topped by a verdigris dome, and behind it, rows of wooden huts. (One newspaper reported, ‘We are reverting to primitive ways. Like disciples of Thoreau we have gone forth and built huts in the woods and by the waters.’) He wasn’t impressed with my hometown. ‘This place is very boring,’ he decided, ‘and I cannot quite believe myself back on England in this unknown region.’ He added a sardonic caption to his postcard of the huge hospital, calling it a ‘Bungalow’.

In this sprawling medicropolis-cum-military resort, a halfway house between the martial and the civilian world, soldiers exchanged their khaki for pale-blue uniforms known as hospital pyjamas. They were loose enough to evoke holiday clothes, perhaps; but they were accessorised by blood-red ties. As an officer, Owen escaped this indignity; he merely wore a blue armband to signify his changed status. He was in limbo, awaiting his assessment as a mentally-rather than physically-wounded man. Half of all shell-shock casualties from the front were cleared through Netley; the fields teemed with traumatised men, a war-damaged crop. Wilfred may not have been able to believe himself in this place as he walked its beach, but I could. Swimming off that same shore, I look over and expect to see him trudging through the shingle, talking to himself.

After a week at Netley, and a stopover in London – where he boasted of writing a letter from a Piccadilly teashop under an opium den, perhaps remembering his decadent friend Tailhade – Owen arrived at Craiglockhart, a down-at-heel hydropathic establishment outside Edinburgh, complete with swimming pool and Turkish baths. It was now occupied by shell-shocked officers shipped there from flooded trenches; some wore nothing but borrowed bathing costumes from the pool. The house magazine, which Owen would edit, was called the Hydra after the mythical many-headed water-snake; but equally it might have evoked the snarling monsters that haunted the men’s dreams.

Military medicine fed on its own victims. But encouraged by his enlightened doctor, Captain Arthur Brock – who had studied in Vienna and who used as a teaching aid a print of a classical sculpture of Hercules and Antaeus wrestling – Owen tried to readjust, ‘chiefly by swimming in the Public Baths really religiously, for it never fails to give me a Greek feeling of energy and elemental life’. An Edinburgh librarian who met him around this time described Owen’s ‘comeliness’: his features fluid and sharp, his compact body like that of a boy, with the muscles of a man; a century later I would meet Owen’s nephew – he had that same short body, that same broad forehead. Yet Wilfred’s physical recovery was not reflected in his face. It had tightened; the slight smile and dark eyes now held a haunted look. It is the same change I see in photographs of my own grandfather: a handsome young soldier in 1914; a haggard man with a lined face just five years later.

I cannot imagine what these men saw. Owen dreamed of his sentry falling back blinded, and of motor accidents, and of a man who received a shrapnel ball ‘just where the wet skin glistened when he swam’, a round red hole ‘like a full-opened sea-anemone’; the wound became infected and he died on the way home, buried at sea along ‘with the anemones off Dover’. The delayed impact of what he had witnessed infected his semi-civilian life. Others who met him then claimed that Owen carried photographs of dead and wounded men in his pocket, a gallery of horror which he would produce as proof of the true effects of war; but in reality, the poetry he was about to write would prove far more effective. By day he wandered the streets of Edinburgh; at night he returned to the trenches. If this city had inspired Jekyll and Hyde, then Stevenson’s story was replayed in the personae of Owen’s fellow officers. At any point they could switch. One moment his friend, a young officer named Mayes, was perfectly normal. The next, he appeared at Wilfred’s door with staring eyes, mouthing words he was unable to utter, making strange gestures with his hands.

Siegfried Sassoon was wearing a purple ‘dressing suit’ on which the sun was shining brilliantly when Wilfred knocked at his bedroom door and asked him to sign his latest book. Sassoon, a hero to Bloomsbury for his rejection of the war’s aims, was of another class entirely: he would refer to Wilfred as ‘little Owen’, and thought him ‘perceptibly provincial’, but also ‘a very loveable creature’. For his part, Wilfred fell in love with Sassoon, innocently, knowingly. Being blown into the air had turned his life around; it was as if he was still falling back to earth. ‘I was always a mad comet,’ he told Siegfried, ‘a dark star in the orbit where you will blaze.’

Now everything changed again. He was introduced to the incrowd. In Edinburgh, Wilfred was invited into an artist’s house where the floor was black and the walls were white, and his hostess wore bright clothes and had her hair cut short. In London he became a house guest of Robbie Ross, Wilde’s lover and literary executor, who had painted his rooms on Half Moon Street gold as a protest against the war, and where every night Turkish delight, brandy and cigarettes were laid out for any friends who might call. These were no unknowing acts on Owen’s part. When he arrived at Robert Graves’s wedding at St James’s, Piccadilly with Ross – all but on the older man’s arm, led in like a faun found in the woods – it was a statement of allegiance. At the party afterwards he met Charles Scott Moncrieff, poet and translator of Proust, who would fall in love with him; both Scott Moncrieff and Ross were about to become entangled in the Pemberton Billing trial, a scandal of conspiracy and prejudice stirred up (not least by a now-embittered Bosie) against Wildean decadence. Wilfred wrote home that he was now ‘one of the ones’. Wilde’s heirs were dangerous people. Owen knew their power; he knew his own. As his biographer Dominic Hibberd wrote, his assault ‘on the civilian conscience’ was a wartime version of the ‘Decadent urge to shock’.

But there was so little time left. In one month, October 1917, he wrote ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’, ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’ and ‘Disabled’. He had barely a year in which to compose the other poems that would make him famous. He told Harold, when they met as soldier and sailor, that his work and the war were ‘running a ghastly race’ – adding, ‘I am getting very tired and short of breath, but I don’t think the War is.’

At the end of October, Owen was judged fit for duty. At first it seemed that he would be kept on the home front. He rejoined his regiment at Scarborough, another resort familiar from his childhood; the beach where he and his family rode horses on the sands was now lined with barbed wire. Scarborough had been shelled by the German fleet in 1914; only two months before Wilfred arrived, it was attacked by an enemy submarine. Some claimed that a German officer had landed from a U-boat and visited one of the town’s pubs.

Wilfred was quartered in a smart hotel with a turret, on the cliff overlooking the North Sea. In between duties as a ‘major domo’ – effectively, a housekeeper to his fellow officers – he went shopping for antiques for his future home, which he had designed even as he lay amid the mud of the trenches, sketching a seaside bungalow, complete with colour scheme and carpets, to which he would escape, like Wilde in his beach hut, once the war was over. After drinking in the town’s oyster bar, Wilfred retreated to his turret from where he could look down on the waves and, wrapping himself in his dressing gown with his feet in purple slippers, became a poet again.

He wrote poems filled with barefoot ‘little gods’ and ‘youthful mariners’, their thighs grasped with muscled arms, and decadent ghosts of Edinburgh alleys and Covent Garden stairs. He read Sherard’s book on Wilde, which steadfastly declined to discuss ‘the aberration which brought this fine life to shipwreck so pitiful’. Between the old world and the new, sex and death mingled, creating new myths. Most particularly, the image of the faun continually recurred in Owen’s work, from ‘Miners’, with its ‘the low sly lives | Before the fauns’, to an untitled poem about the son of friends in Edinburgh: ‘Sweet is your antique body, not yet young,’ among ‘sly fauns and trees’.

There was a knowing innocence in these shape-shifters – from Peter Pan, who would never grow up, to the teenaged C.S. Lewis’s dream, in 1914, of a faun carrying parcels and an umbrella in a snowy wood. Even the boy actor Noël Coward – whom Scott Moncrieff would bring to Half Moon Street, fresh from swimming naked at Babbacombe – wrote a youthful novel about the daughter of Pan. But these hybrids, neither one thing nor the other, were also subvert emblems of a queer nature; they persisted through history, mixing myth with apprehension, if not a little fear. It is telling, given the moral outrage of the times, to note that the word panic derives from this amoral creature. Its disruptions reached back to Keats’s fauns and Shelley’s satyrs and Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Flush as Faunus; from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Marble Faun to Herman Melville’s androgynous young Harry Bolton, ‘a mixed being’ who looked like a zebra or one of ‘the centaurs of fancy; half real and human, half wild and grotesque’; and on to Aubrey Beardsley’s lascivious beings, the sight of Nijinsky, a horned, piebald, cold-eyed faun falling wanking to the floor, and the future vision of a star who was half dog, a wild mutation.

Slipping between species, a boy could escape, into the sea or up to the sky. One of Wilfred’s prizes from Scarborough was a bronze statuette of Hermes, god of flight, father to Pan and Hermaphroditus, a muscular form with a winged cap. The dark little deity seemed like a simulacrum of his fantastical self which he might have carried into battle if he could, with feathers sprouting out of his army cap.

Half poet, half soldier in his khaki slacks, bare torso, dark hair and slanting eyes, Owen was acting out a rite of his own duality. It was how he saw himself. In a light-hearted letter to his mother, written in the heat of the summer in France, resting in the limbo of the American field hospital, he had described his appearance: ‘Clothing: sparse, almost faun.’ He certainly seemed so in Osbert Sitwell’s description of his small sturdy figure, with a broad forehead, wide-apart, deep-coloured eyes and ‘tawny, rather sanguine skin’; young for his age, with an eager, shy air, soft, warm voice and a ready smile. He was a twentieth-century faun, picking his way across the trenches on his goat-like feet and holding not an umbrella, but a Webley revolver.

The war had not forgotten its claim on him. As the last days of 1917 turned into a new year, Owen felt confident in telling his mother, ‘I am a poet’s poet. I am started. The tugs have left me; I feel the great swelling of the open sea taking my galleon.’ It was now certain that, despite Scott Moncrieff’s efforts at the War Office to get him a home posting, he would be sent back to the front. Back in Shrewsbury, he met up with Harold. They stayed up late, talking into the night. Wilfred seemed about to take his brother into his confidence about his private life, but it was clear from Harold’s attitude that any such statement would be impossible. To him, love between men was ‘horrible’, ‘repugnant’, ‘revolting’. Wilfred made a joke about the supposed purity of sailors, but he had no hope of making a confession on this, their last evening together.

Pronounced fit for overseas duty, posted to a vast army camp at Ripon in Yorkshire, Owen found a river, the Ure, in which to bathe. ‘I am rather weary now,’ he told his sister Mary, writing at midnight in his tent, ‘having Swum this afternoon, and – in consequence of the exercise –, having written a promising poem this evening.’ The poem was ‘Mental Cases’. He apologised to her for his exuberance. ‘It comes of my recent baptism in the pleasant waters of this River. It was an amusing afternoon.’

He’d walked miles to find the bathing place, only to discover a sign reserving it ‘for the Civilian Population on Wednesdays!’ He decided that the civilians of Yorkshire would not be dismayed to share the river with an officer such as himself. But even here there were omens. One of the young cadets dived into the water, which was just two feet deep, ‘losing his head with joy … and nearly lost it again. He cut it open, but as there was no brandy, he decided not to faint, and I got him safe into a cab.’ Wilfred never knew that the boy later died of his injuries.

On 31 August, he got ready to leave England. Having said goodbye to Sassoon in London, and after spending the evening with Scott Moncrieff, he rose at 5 a.m., and took the seven-thirty train to Folkestone.

As I leave the station I ask a passing youth for directions to the sea. He just keeps on walking, pulling up his hoodie, declining to meet my eyes. ‘I’m not from round here, mate.’

It’s not difficult to see where I must ride. The streets lead down to the harbour, its arm arching out into the Channel, ending in a lighthouse. The disused boat-train station still stands, its platforms deserted, glass awning cracked, rails rusty. On either side is the sea, the only place left to go. In the distance are the chalk cliffs of Dover.

By 1918, this resort had suffered greatly. One German bomb, dropped on the street I have just cycled down, killed sixty people, mostly women and children. Folkestone was filled with refugees and soldiers. It was continually saying goodbye. Ten million troops had passed through its port; here the war had been leaking into England for four years, and England leaking into the war. You had only to step from the train and into France, twenty-three miles away. You could see it from the cliffs through a coin-in-the-slot telescope: a dark line on the horizon.

It was the last day of August. A hot, sunny day. Improbable that he was leaving England at all.

‘But these are not Lines written in Dejection,’ he told Sassoon. ‘Serenity Shelley never dreamed of crowns me. Will it last when I shall have gone into Caverns & Abysmals such as he never reserved for his worst daemons?’ He was oddly cheerful. ‘I went down to Folkestone Beach and into the sea, thinking to go through those stanzas & emotions of Shelley’s to the full. But I was too happy, or the Sun was too supreme.’

‘I sit upon the sands alone,’ Shelley had written, but Wilfred told his mother, ‘my last hours in England were brightened by a bathe in the fair green Channel, in company of the best piece of Nation left in England – a Harrow boy …’ To Sassoon, he was more revealing about this shining encounter. ‘Moreover there issued from the sea distraction, in the shape, Shape I say, but lay no stress on that, of a Harrow boy, of superb intellect & refinement; intellect because he hates war more than Germans; refinement because of the way he spoke of my Going, and of the Sun, and of the Sea there; and the way he spoke of Everything. In fact, the way he spoke –’

He left his words hanging, with that boy, on that beach.

A lifetime ago another boy on another beach, Russell Tarr, had represented a new world. This unnamed Harrovian represented the last of England. He was the summation of other youths, like the ‘navy boy’ with whom Wilfred had shared a train compartment, golden-headed and fresh-faced, the seaman his father had always wanted him to be: ‘Strong were his silken muscles hiddenly | As under currents where the waters smile.’ ‘And as we talked, some things he said to me | Not knowing, cleansed me of a cowardice, | As I had braced me in the dangerous sea.’ What if he had followed his father’s desires, or his own? Would they, or the sea, have saved him?

He was going back to France, not for the love of his nation, but for the love of his men. ‘I came out in order to help these boys,’ he told his mother; to lead them as their officer, speak for their suffering. On that last day in Folkestone, Owen knew where to go: he had been here before, when he’d first shipped out from England as a soldier, back in 1916. After waiting for his shave – taking the time in the Saturday-morning queue to write a postcard home – he returned to the shore.

Wilfred, the lone wolf, on the beach.

People on the promenade, eating fish and chips, taking the air. Bands playing. Pierrots, made up in black and white, entertaining the crowds. On the streets, on trains, in canteens and shops and pubs and cafés, the civilian mixed with the military, blurring cups of tea with orders to advance. The tide coming in, and going out.

I wonder where he undressed, struggling to preserve his decency under a towel. Was he going back to war with his woollen bathers in his kitbag? The warm sun must have felt good on his tanned body, trained by war for war.

I watch him as he leaves his uniform neatly folded in a pile, striding into the sea on his short legs, feeling its rising, exhilarating chill, pushing through the waves, the water slicking back his short hair, as sleek as a selkie.

I follow him, into the surf. It’s high tide, cold and green, washed with the light of the white cliffs.

For a few minutes, on that beach, under the sun, everything intensified by the light, the sea was his saviour. If he’d stayed in a little longer, everything might have changed with the next tide.

But soon he was back in uniform and boarding the three o’clock boat, bound for France.

Nearly sixty years later, eighty years old, Owen introduced me to poetry; after all, he’d been a teacher himself. In the wood-and-glass-panelled classroom of my school – run by monks in black cassocks powdered with chalk dust – our civilian English master, a harried-looking man in an academic gown, handed out the poems. Their clarion words – ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ – spoke to my teenage self-drama; they seemed to be written by someone like me, not a remote poet from the past; he was part of my resistance against the normal world. Poets could time-travel, I realised, like the starman. They also died young. In a world in which I was promised five years left to cry in, his words were ambivalent, the way I felt. I heard his voice over war cries from autumnal football pitches. I peered at his photograph, the one in all the books, its half-smile receding with each reproduction of this ordinary, handsome man.

I still cannot look enough. I had no idea of how like or unlike me he had been. I did not know him for a boy from a semi-detached house where he read his books in his boxroom, or that he walked the same shore as I did.

I turn to tell him, as he stands by my side on the beach, that he is better off, that the century isn’t worth waiting for.

A few days after returning to France, Wilfred finished his poem ‘Spring Offensive’. In it, he wrote of the soldiers he served; men who had come to ‘the end of the world’, where they ‘breasted the surf of bullets’. ‘Some say God caught them even before they fell’; others succumbed in the sea of mud. The dead were drowned and forgotten, as he wrote in the last line he would ever compose.

Why speak not they of comrades that went under?

The final attacks of the war were made by soldiers wearing life-jackets taken from cross-Channel ferries, advancing in the fog through flooded fields. Owen went back into battle, accompanied by ‘Little Jones’, his manservant pledged to protect his officer’s life. Moments later Jones was shot. The two men lay together on a hillside as the servant’s blood poured onto his master, ‘the boy by my side, shot through the head, lay on top of me, soaking my shoulder, for half an hour’, Wilfred wrote to Siegfried. ‘Catalogue? Photograph? Can you photograph the crimson-hot iron as it cools from the smelting? That is what Jones’s blood looked like, and felt like.’

He became his myth. Leading his men on with a new, ‘seraphic’ lance corporal by his side, further ahead of the line than anyone else, he roared, fighting ‘like an angel’, capturing a German machine gun and personally inflicting, as his citation would report, ‘considerable losses’ on the enemy. For this he became a hero; for this he won a medal he would never wear. He was an avenging angel, tooled up, dealing death. In the dark, chilled to the bone, another corporal produced a blanket and shared it with his officer. And before the dawn, in the hour between wolf and dog when the night sank to its coldest, acting Captain Owen led his men back under the stars, ‘through an air mysterious with poison gas’, recalling enough of his astronomy to assure them that it was early morning. In between the frenzied, halting action he read Swinburne, another poet sensually attached to the water. It was the only book he had left; only poetry was any good now. In another lull in the fighting, his platoon were entertained by the bizarre sight of seaside pierrots and soldiers performing in drag, all but limelit by the falling flares, like the ghosts they all already were. He had never loved his men more, and longed to tell them the war was about to end, any day now.

Four days later the company took shelter in a cottage on the edge of the Mormal Forest, which might have contained magical animals, ready for the last battle. Holed up in a vaulted brick cellar, Owen and his men planned their next attack. It was the fourth of November. Back home, boys were getting ready to light fireworks.

The Sambre–Oise canal ran through the flatlands, forty feet wide and eight feet deep, too deep to ford; a man might be lost in it. Six months before, the occupying German soldiers had jumped into this water. Naked, some still wearing their caps. Laughing. Alive. They might have been modern youths tombstoning into Torbay. This could be the Wannsee or the Serpentine. Young willows sprout from the bank.

Weeks later, as they retreated, their sappers flooded the land to forestall their pursuers. More than ever, this world was water, and its assailants sailors. The advancing British built makeshift rafts from poles and petrol cans, like lads messing about on a river. On these they tried to cross the canal, only to come under fire from young men like themselves.

Owen was last seen standing on one of the rafts before he was shot.

The dark water flowed below him, overlooked by silent trees.