If Tara is air and the flight of birds, Newgrange is wood and stone and water. If Tara is the sovereignty of the king, Newgrange is the sacred space far more powerful and more ancient than any sovereign’s power. The concentration of great tombs at the bend of the River Boyne in County Meath (Brú na Bóinne, ‘The Mansion or dwelling Place on the Boyne’, also translated as ‘The Bend of the Boyne’) constitutes one of the most important centres of Neolithic antiquities in Ireland, and indeed in Europe. To reach Newgrange, you move slowly down roads which follow the bends of the river, past old stone farmhouses half-covered in green moss, through a landscape that has been cultivated by man from a time beyond time – a rich land, a quiet people; long before Maeve led her armies towards Ulster in battle for a great bull, the people here herded their cattle quietly, paying homage to the Bóinn, the cow-goddess of the river. The remains at Newgrange are from long before the time of the Celtic warrior society that produced the stories of the Táin. Knowth and Newgrange have been dated through excavation to around 2500BC, making them older than Stonehenge, Mycenae or the pyramids of Egypt. The Newgrange site remained sacred, a burial place for pre-Christian kings, and known and honoured at least until Roman times, but at some point after this the secrets of the mounds were lost. Newgrange became part of the possessions of the monks of Mellifont Abbey, a grassy hill for grazing cattle. The great tombs slipped quietly into the quiet land of Meath, and were left without interference until the beginning of the modern age. Then, at the end of the seventeenth century, a local landowner was quarrying stone, and stumbled onto the entrance to the chamber of the great mound at Newgrange.

Since then, the mound has been continuously studied, and, in the middle of the last century, Newgrange was excavated and the exterior reconstructed in line with the evidence available. Now the great mound is a sparkling white quartz-covered circle on the green hillside. Newgrange is one of many mounds in the Brú na Bóinne complex. It is the largest and most dramatic of the tombs, sited on a hill looking down towards the river, with its entrance aligned towards the mid-winter solstice sunrise. Before the archaeologists had discovered the alignment of the roof-box over the entrance to the great passage, situated so that it lights the furthest recess in the tomb at dawn on the winter solstice, they had been told of a local tradition that held that the rising sun at some point in the year lit those same three spiral stones. The astronomical and engineering skills of a people who lived almost 5,000 years ago have also resulted in a structure that keeps the inner space as dry as a bone and silent as a tomb, where the temperature stays at a steady 10 degrees.

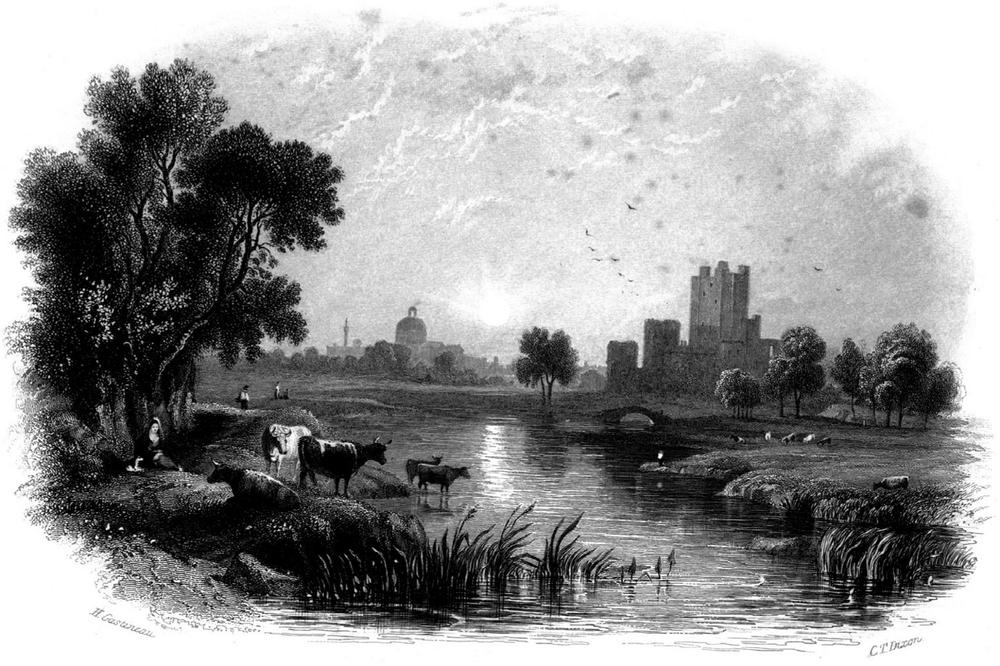

The River Boyne.

The other main ritual centres of the Boyne complex are Knowth and Dowth. Unlike Newgrange with its single mound, at Knowth you can spend time wandering through the ritual area marked by seventeen satellite mounds scattered around the central tomb. It is now also possible to visit the inside of this central mound. While Newgrange has one passage leading into the burial chamber, Knowth has two long passages leading into the centre under the great mound. Its orientation is hotly disputed, with theories put forward of equinoctical or possibly even lunar alignment. It should be visited as part of a trip to the complex, not least because the carved stones here are incredible examples of Megalithic art – in fact, the Knowth tombs constitute 30 per cent of the known Megalithic art of Europe. Newgrange and Knowth can be visited only as part of a guided tour from the excellent interpretative centre, and as there is limited access, it makes sense to come very early in the day.

The visitor centre supplies a wealth of archaeological information. The archaeologists can tell us that while there is evidence of burials in the mounds, it seems highly unlikely that these huge, complex structures were built as individual tombs. They can also give us a great deal of information on how these structures were made. However, what they cannot give us is definitive answers as to the meaning behind all this human effort. The experts cannot say why these people carved rocks with spirals, with lozenges, and, in one case, with a single fern. They cannot say why the stones were painstakingly shaped and carried from districts far away. Why did these people make the bowl-like depressions in the recess stones, which may have held some form of liquid? Are the carvings on the stones astronomical maps or messages in some lost shamanistic language that we can no longer read? Is the carving on the stone marking the western entrance of the main tomb at Knowth, resembling so closely a human face with an open, screaming mouth, the ‘guardian stone’ as it has been named, or something else completely? In the absence of definitive scientific answers, theories abound.

Plan of the gallery at Newgrange, County Meath.

What is sure is that these places acted as treasuries for the people who lived 5,000 years ago – treasuries not of material wealth, but of their deepest feelings and thoughts about how the cosmos functioned. If we take our leave of the archaeologists and go back to the legends, we are told that Aonghus, the young god, the god of lovers, brought the beloved dead to the Brú. Here he took Diarmaid and breathed life into him for a time every day so that he could converse with him in the dark house of the dead. Here, in this same chamber, light breaks in on the darkest day of the year. Here, by some power of love – whether human, emanating from the memory of the tribe, or divine, emanating from the power of their gods – here, in some sense, the dead lived and spoke to the living.

Close to Newgrange and a further integral part of the Brú na Bóinne complex was the royal house of Cleiteach, although there are conflicting theories about its exact location. Some authorities site it near Stackallen Bridge, which is located some miles from Newgrange on the Boyne. This is the theory put forward by the great nineteenth-century Gaelic scholar and place-name expert John O’Donovan, who suggests this place as a possibility in his Ordnance Survey letters. However, O’Donovan was not at all adamant about this theory; originally he sited Cleiteach at Clady, a hill on the northern bank of the Boyne, one mile north of Bective; later, he admitted that this must be wrong, and walked the length of the river trying to find the site. It was then that he put forward the possibility of Cletty being one of the mounds on the river near Stackallen at Broadboyne bridge. Later in the century, William Wilde, father of the famous Oscar, suggested either Clady or Assay as possible sites. There was little further investigation until Elizabeth Hickey, in 1965, made a convincing argument about the location of Cleiteach, based on geographical features and the physical landscape linked with the written sources, suggesting that the site of Cleiteach might be at Rosnaree House, near Newgrange itself.

Rosnaree, the wooded headland of the kings, is the place where the great high king, Cormac, is believed to be buried. He moved to Cleiteach from Tara after he gave up the high kingship because of physical disability, and died there when a salmon bone caught in his throat. At his funeral, as he was carried across the River Boyne, it rose up, refusing to let him be buried with the pagan kings at Newgrange. According to some accounts, Cleiteach is also the place where the god Nuadhu lived when banished from Newgrange by Aonghus Óg, and also where Fionn tasted the Salmon of Knowledge and gained the power of foreseeing.

Perhaps the specific site of the original Cleiteach, which was destroyed in a great fire in the sixth century during the reign of Muircheartach Mac Earca, is not really so important. The course of the River Boyne itself has been much altered by canalisation and by dredging. Its leafy banks, however, still repay the visitor with a sense of luxuriant, slow-moving power. Because it can sometimes be hard to connect with the ancient power of Newgrange, surrounded as we are by other people during the visit, it is worthwhile to spend time at the quieter places along the banks of the river. To visit the ancient graveyard at Ardmulchan, for example, when evening light turns the grass to a golden green, and to watch the river as it curves past the Norman castle and Celtic crosses, is to feel something akin to the kind of power that one feels at Knockainey in Limerick. In both these places, the land is rich and has been cultivated for a very long time, and the goddess that was honoured here is one associated with fertile land and herds. In one story, Bóinn, the goddess of the Boyne and mother of Aonghus, the Lord of Newgrange, was drowned and became the river when she opened the well of Segais. This mythical well was the source of wisdom where the nine hazel trees grew and dropped their nuts and berries in the water, there to be swallowed by the salmon of wisdom, the salmon which gave Fionn his powers of foreseeing. Bóinn flowed past Brú na Bóinne, one of the most important access points to the otherworld. And it had been at the Brú that she had betrayed her husband Elcmar when she lay with the Daghdha. On a night which the Daghdha made last for years, their mating engendered Aonghus. The Dindshenchas, the lore of places, calls on Bóinn as one of the great ones, the rulers of the landscape. Her name associates her strongly with cows (bó being the Irish word for cow), and there are echoes of her power well into the nineteenth century when O’Donovan recorded that local farmers drove their cattle through the River Boyne as a charm against the powers of the Sídh.

Sunlight floods the passage grave at Newgrange.

In historical times, the river was the site of the famous and bloody Battle of the Boyne between James II and William of Orange. Walking along its quiet banks, it is hard to imagine any violence or hatred disturbing the peaceful realm of this gentle goddess. However, the following story shows that things could be otherwise.

THE REVENGE OF SÍN

When the great king, Muircheartach Mac Erca, came back from a hunting-trip with a strange and beautiful woman, there was much talking among his people, for it was whispered that she had appeared out of nowhere while he sat apart from his companions on the hunting mound at the Brú. Many thought that she must be a fairy woman come out of the mounds, for her beauty seemed not of this world. It was a dangerous thing to do – to hunt alone at the time of Samhain, when the leaves were turning and beginning to fall in fiery drifts, and the great forests on the banks of the Boyne were transformed into a copper and crimson melting pot. Outside the houses, cold air solidified into a mist when man or beast breathed out, mingling with the vapour that rose from the river. Inside the houses, there were great fires and feasts, and songs celebrating a king whose victories had brought all the tribes under his power, who had left dead bodies as countless as the leaves that fell from the trees, crushed underfoot into the earth. A tall, dark-haired man with a heavy beard and a searching eye, Muircheartach was generous and hospitable; his house at Cletty was always full of guests, of poets and musicians and brave warriors.

The people loved and trusted their king; so although they whispered when the woman came to Cletty, they did not demur. However, when Muircheartach put his wife, Duaibhseach, and his own children out of the house, his people began to worry that he was under an enchantment that would bring evil to the realm. And while the woman, Sín, was indeed beautiful, with her slanted amber eyes and bronze hair, it was a strange, sly beauty, a beauty without gentleness, and her power over the king was such that he could do nothing but watch her while she moved or spoke or sang. Then the king commanded that, at his beloved’s request, no cleric should enter Cletty while the lady Sín resided there.

Duaibhseach, proud and a princess in her own right, went, red-eyed, to the hermit Cairneach and complained of her treatment, and he went and stood in front of the great house – one of the finest and strongest in Ireland – and cursed Muircheartach for his evil-doing.

However, Sín, looking from the ramparts with Muircheartach, laughed and said to the king, ‘Do not worry about the curse the greasy cleric puts on you. He cannot harm you with his bells and his books while I am here to protect you, for my magic is stronger than his.’

Muircheartach looked at her lovely form, and thought of the knowledge that she had, which he thirsted after as he might after wine or her body, and asked the question he had wanted to ask from the first moment he had seen her: ‘Are you human, then, or a woman of the Sídh?’

Sín smiled and said, ‘I am human like you, but I have knowledge that could make wonders happen before your eyes. I could make the Boyne water into wine, and change the very stones on the hills into flocks of sheep, and the ferns that grow all around Cletty into fat swine. Ask me what you will.’

So Muircheartach asked her to perform these deeds, and before his eyes she changed the stones around the dún into blue men who battled with another army which she made from goats – a horrible goblin crew which had kept their animal heads, horns and all, but had the bodies of warriors. It was a brave battle the couple watched, and when it was over, Sín brought the king and his household inside and took three casks of water which she changed into a wine the like of which the king had never before tasted. Then she fed the host with magic swine which she had created from ferns. It was a wild feast that night, but one that gave those that partook of it no nourishment. The next day, the king and his army could hardly move from their beds, for their strength had been sapped by the enchanted food and drink.

Now, Sín had power over the king and all his court, so it seemed to them that battalions of the blue men and other creatures without heads were attacking the house, and the king and his warriors went out to do battle with this phantom army, not realising that the witch had made the demons of stones and sods and the green growing things of the riverbank. So it continued, with the king moving further and further into a world of dark enchantment – feasting at night on magic food that left him weak in the morning, and further weakened during the day by the senseless battling with the goblin army created by Sín. The clerics tried to cure him of the enchantment, but as soon as he returned to Sín, his eyes were blinded once again.

This went on, then, until the Wednesday night after All Saints’ Day, when a winter wind came over the land, and Sín called out her names of Sigh and Wind and Winter, Storm and Grief. First, thunder and lightning flashed, and then she made a great snowstorm come down, which enveloped the house at Cletty and the sleeping king. He awoke screaming in the darkness, having seen fire and destruction, forewarning him of the fate that he was bringing upon himself. Twice he awoke from nightmares but each time the lady Sín gave him enchanted wine and he fell back into a drugged sleep. The third time, he awoke to find the house ablaze, and all his retainers fled, for as he slept, Sín had lit red fires in every corner of the mansion. She had put each weapon in the place with its point facing inward and had set a demon army battling outside, so that the king thought that the house was surrounded by enemies. Fire burst from every doorpost and window ledge. Muircheartach ran around in frenzy, trying to find a way out, but everywhere was blocked by flame and crashing timbers. The flickering leaves of the fire fell on his head and his shoulders, and terror came into his heart – a terror that he had never known in battle. Yet still the frenzy that Sín had put on him clouded his brain and his eyes, so that everywhere he looked he saw someone ready to attack him, and he fought the very tables and benches wildly, as if they had been mortal enemies.

Muircheartach begged Sín to save him, to make a path for him through the flames, but she turned her back and disappeared. With her cloak of invisibility about her, Sín stood and watched, until the flames grew too hot and bright and she left Muircheartach to his fate. He ran screaming through the house, the flames biting at him like angry teeth. Finally, in desperation, he climbed into a cask of wine, but the flames fell on his head, and burnt it, leaving the rest of his body whole. So it was said that the king was both burned and drowned.

Cairneach buried Muircheartach with the respect due to a great king. Duaibhseach came to her husband’s graveside and lamented, and they say that she finally fell dead from grief. Then the clerics saw a most beautiful lady approaching them – so lovely that some of them turned their eyes to the ground to keep their minds from evil thoughts, while others could not look away from her. Long red hair fell over a green mantle with a silver fringe, and her beautiful countenance was made even lovelier by the loneliness and sadness of her face.

‘Who are you?’ they asked.

‘I am Sín, daughter of King Sige. I am the one who brought this king to his death.’

‘And why did you do this?’ they asked.

‘Muircheartach, dead here before you, killed my father and my mother and my sister at the battle of Cerb; he destroyed all my family, all the old tribes of Tara, and took the land of my people away from them. I was only a child when that happened, but I swore that I would gain vengeance on him and I learned the skills of magic so that I could do so.’ She paused, and the face she turned to Cairneach was the bleakest he had ever seen.

‘But despite all my knowledge and foreseeing, what I did not know was that I myself would fall under a spell – that I would love this man for his strength and his courage, his kindness and generosity; for his smile and the way the hair curled at the back of his neck. That is the revenge fate has had upon me.’

It is said that then she too died, from her grief at the death that she herself had brought about, and that although she had been an enchantress and the murderer of a great king, because of her beauty and her sorrow, Cairneach took pity on her and buried her in hallowed ground.