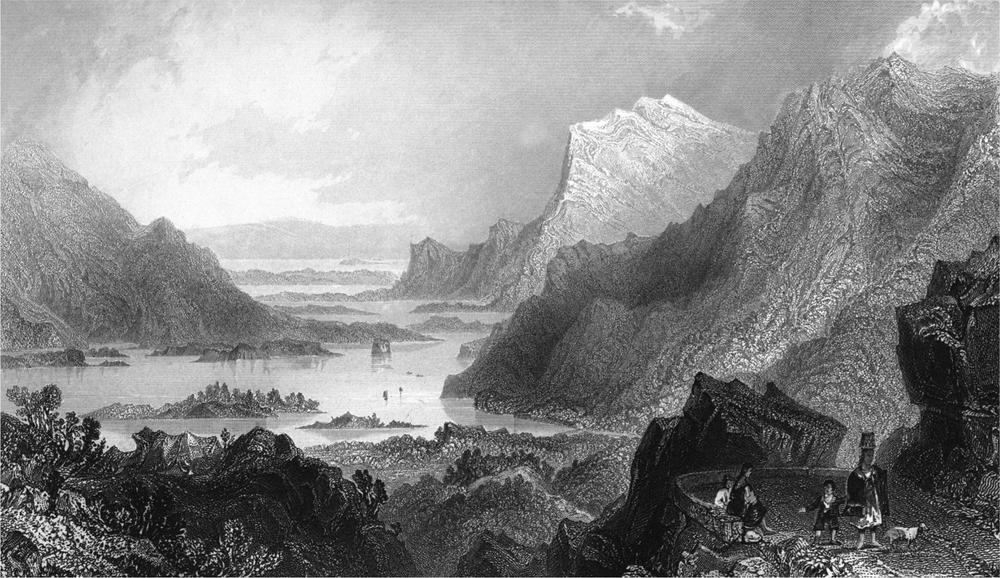

By any standards, the district surrounding the Lakes of Killarney is incredibly beautiful. Killarney (Cill Áirne, ‘Church of the Sloe’) is situated in County Kerry, between the Macgillicuddy Reeks and the Mangerton Mountains, close to the influence of the warm Gulf Stream, which results in a landscape that contains a wide variety of luxuriant vegetation. The particular combination of the high, rugged mountains (the highest in Ireland), the three lakes, the woodland and the many islands dotting the lakes makes the district one of stupendous natural beauty. Up until the early nineteenth century, this was a wild and isolated spot – the haunt of highwaymen, some of whom are still remembered in the names of the caves where they hid in the mountains. The area has suffered, however, more than any part of Ireland from a feeling of tourist overkill – the lakes have left the kingdom of Kerry and entered the kingdom of cliché. During the nineteenth century, everybody who was anybody visited the lakes, and usually wrote about them, for they saw in this place the epitome of a romantic landscape. Wordsworth and Tennyson, Thackeray and those indefatigable travellers, the Halls, Charlotte Brontë (who came here on her honeymoon), even Queen Victoria – they came, they saw, and they rhapsodised with various degrees of romantic hyperbole. The pattern continued into the twentieth century, when the area became a Mecca for transatlantic visitors. There was an exponential growth of tourist attractions such as Kate Kearney’s cottage and the Colleen Bawn’s rock – all to be visited by jaunting car, if possible.

WH Bartlett’s nineteenth-century engraving depicting the ‘Approach to Killarney from the Kenmare Road’.

The legend of Oisín, which is associated with Lough Leane, is the most recent in this book, although it stems from a much older tradition which has Oisín returning to Ireland after hundreds of years. He had many long conversations with St Patrick, in which they discussed the relative values of the old, wild, heroic days and the new, gentler order; and it must be said that his case for the old world view often makes it seem the more attractive time. Oisín is commemorated in the road which runs down the Iveragh Peninsula, which is signposted as Bealach Oisín.

Killarney itself is a pleasant enough town, though there is a palpable feeling of a place that feeds on tourism. The establishment of a National Park has at least had the result of preventing the expansion of hotels and restaurants in the most beautiful areas around the lakes, and it is still possible, with a little effort, to strip away the Disneyland associations and connect with the place as it must have been before the tourist invasion of the last two centuries.

Such a place is sometimes wild and terrible, especially when the storms that are a regular feature of such a mountainous region lash down on the rocks and whip the waters of the lakes into a black frenzy. However, it can also seem to be the most serene place on the planet, in early morning when the still water of the lakes is glimpsed through the ancient oak woodlands. There are three main lakes in Killarney – the Upper Lake, the smallest of the three, high in the mountains near the gap of Dunloe; the Middle Lake or Muckross Lake, on the banks of which stands the impressive Muckross Abbey and a useful information centre; and the largest of the three, Lough Leane or the Lower Lake, nearest the town itself and dotted with thirty islands. Lough Leane is said to be named after a retainer of the god Bodhbh from Slievenamon who was called Len Linfiaclach.

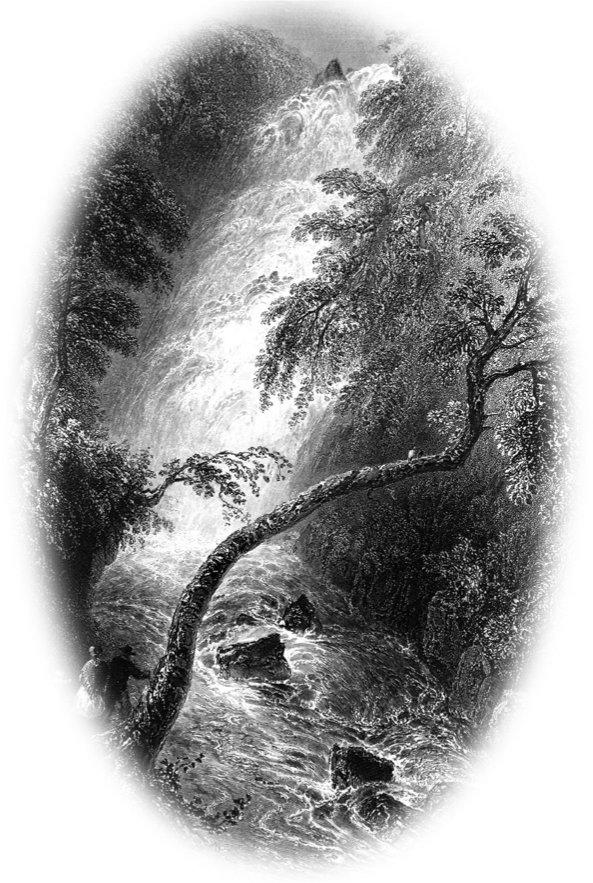

‘The Torc Cascade’, County Kerry, engraving by WH Bartlett.

It is possible to take a boat trip on the lakes and visit some of the islands. Many of these are covered with semi-tropical vegetation, such as bamboo and eucalyptus. In June, the colours of the rhododendron are stunning. The plant is not a native one but has flourished so wildly in the warm temperate climate of the south of Ireland that, despite its beauty, it is now considered a pest and a threat to native species. On Inisfallen island there are the ruins of an abbey, reputedly founded by St Finian the Leper, where the Annals of Innisfallen – a seminal source of early Irish history – were written between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries. Other areas of exceptional beauty include the Torc waterfall and the gap of Dunloe to the south of Lough Leane. It is worthwhile to make the effort to get away from the more popular sites, where hordes of tourists are disgorged from the maws of coaches. If you are very lucky, in the high upland areas, you may see one of the herds of the red deer, a species which has roamed the Irish countryside for thousands of years. Alternatively, choose a wet day for your trip, preferably with an odd roll of thunder and flash of lightning thrown in. Most of the crowds will have taken refuge inside the restaurants and you will be able enter into the wildness of the place. And if the mountains are not as visible as you might like, you may lose yourself instead in the wet, green world of the ancient woodlands. In this world, if you hear a clattering of horse’s hooves in the distance, it will be easier to imagine that this is not yet another jaunting car, carrying a shivering tourist desperate for the sight of a thatched cottage which serves cappuccino, but rather the horse of a woman of the Sídh, coming from the other side of the mist in search of her human lover.

THE RETURN OF OISÍN

I am fallen here, in this Wicklow glen, like a dead leaf on the floor of the forest. I am the dried husk of summer, waiting to be crushed into the earth, unable to move without the help of those who, a moment ago, thought me some kind of god. They look down at me, horrified; one minute they were seeing a fine warrior on a white horse, the next minute an ancient withered man, transformed as soon as I touched the soil of Ireland. The people’s faces are coarse and cowardly, their limbs puny; I have seen no one here that has a quarter of the strength or nobility of my companions of old. But every one of them is stronger than me now.

Yet the summer is as sweet as it ever was, though the noise of the forest is torture to me now, in this woody glen, so full of life. Full of sap rising, birds building, bees humming, linnets, thrushes, and ringdoves. All is flowering, all is alive and full to bursting. And the bells of the Christian priests tell me over and over again that my world has gone.

It was in another such beautiful glen, in autumn, that I hunted with my father, Fionn Mac Cumhaill, and my son, Oscar, near Loch Leane in the south. In autumn, that place has the saddest beauty, the beauty of a world about to change. It was a clear, cold morning that we started out.

‘Oisín,’ my father called out. ‘You take your company down by the lake. I think there are the tracks of a young fawn down there.’

I nodded, although I resented my father telling me how to go about the hunt. I knew I still had things to learn from him about woodcraft and magic, but he was no longer the man he had once been; bitter lines had been etched on his mouth since Diarmaid’s betrayal of him and his of Diarmaid. Lines were on his forehead from the long battle with his old companion, Goll. Yet still I felt as if I walked in his shadow. But as I made my way down towards the lakeside, I forgot him in my joy in the beauty of the mountains and the water and the excitement of the hunt.

Then I stopped, for riding towards me over the hillside was the most beautiful woman I had ever seen. Her skin was whiter than a white rose. Her hair was the gold of the sun, her eyes the colour of a thrush’s egg. She rode a fine white horse, with golden reins and saddle, and as she came towards me, I could see that her eyes were shining with joy.

‘I have found you at last,’ she said as she approached me. ‘Oisín, I have sought you long, and come so far to find you, for I have seen you in dreams and I know that you are my heart’s match.’

I could say nothing. I, Oisín, the great poet and teller of tales, was struck dumb by her loveliness.’

‘Will you come with me?’ she asked sweetly. ‘I am Niamh, Princess of the Golden Hair, and I have come from the Land of Pleasure to take you back there with me as my husband. Will you come with me?’

I was so overtaken with desire for this lovely woman that had she asked me to go with her anywhere in this world or any other, I would have left without a backwards look. I saw nothing, neither my father nor my son coming up behind me, calling me. I went to her, and she pulled me onto her horse. We rode like the wind away from that place, leaving my companions calling behind me. The journey took us over seas and plains and mountains, and far beyond the land of Ireland; finally, we reached her father’s place. They treated me with great honour there and I lived with my sweet bride for what seemed to me to be three years, and had a son and a daughter by her. I lived a life of pleasure – of hunting and feasting and laughter. But one day I awoke with a longing in my heart to see my companions again, and my son Oscar and the fair land of Ireland, and even my father; for I thought that now I should no longer feel that I lived in his shadow, having lived so long in the bright sunlight of the other world. I imagined the stories I would have to tell them, how they would listen to me in wonder. So finally I went to Niamh and said, ‘My sweetheart, you know I love you better than life itself, but I feel that I must visit my family and my companions. Will you come with me that you may be welcomed by my people as I have been welcomed by yours?’

Niamh’s hands fell from her needlework.

‘Oisín,’ she said. ‘Let me ask you not to do this. I cannot come with you and I fear that you will not return if you leave me to visit Ireland.’

‘My love,’ I said firmly. ‘Nothing would keep me away from you. If you will not come with me, let me go alone. I will return before you know that I have gone.’

My wife nodded. ‘So the day I dreaded has come. So be it, then. But take the white horse we rode on to come here; and promise me one thing – that you will not dismount from his back no matter what happens. Promise me that, if nothing else.’

I laughed a little – so this was her trick to make sure that my visit was a short one! But she looked so disconsolate that I promised what she wished.

The white horse carried me like the wind to Ireland; but it was not the Ireland of my youth. It seemed as if a race of dwarfs – ugly, misshapen weaklings – had taken over the island. I rode through the valleys asking the people for news of Fionn and the Fianna, but no one seemed to know what I was talking about. Everyone looked blank, except for one very old man who said that he had heard stories of such heroes who had dwelt in the forests three hundred years before. Slowly, I began to realise that what had passed for a year in the Land of the Young was a hundred years in the world of mortals; my father, my child and my companions had long since become white bones, rotted into the land itself.

Yet still I rode through the countryside, for although the people had changed, the land remained familiar, and I hoped to find the traces of my lost world. Finally, I came here to Gleann na Smól, the valley of thrushes, where I met a group of men trying to shift a heavy boulder. They begged me to help them, for like the rest of the inhabitants they were a puny lot. I leaned from the back of the white horse to shift the stone, and as I did so, a bell rang out from a neighbouring valley and the horse bolted, throwing me to the ground. As soon as I touched earth, I felt my flesh wither, my eyes fade, my strength seep from me. Within seconds, I was an ancient heap of skin and bones, and the white horse had galloped off, back to the fair princess I would never see again.

Always, those who leave expect to come back to the same world. They want it to be unchanged – the same companions opening their arms to welcome them; the girls they left years before as young and pretty as ever; their friends gathered together, agog to hear stories of adventure. But those who leave never come back to the same place. Indeed, now I sometimes wonder if that lost world really existed – if my memory has recreated it in brighter colours than the ones it actually held. When I tell these people of how the world was when I was young, I can see that they only half-believe me. They smile behind their hands to see me weep, but I will weep my fill, because Fionn and the Fianna are no longer living. They look at my withered flesh and offer to bring me to the man who is preaching of a new god. His name is Patrick and he talks of something called the soul and promises eternal life.

I do not want eternal life. I would sell what the Christians call my soul to have only one day of my youth again – to be alive and strong and a part of the green world, to hear the hounds baying in the forest, the sweet note of the blackbird, and my companions calling me to the hunt.