The story of the Children of Lir is most commonly associated with beautiful Lake Derravaragh in County Westmeath. In many ways, however, the legend of Lir’s children is a story of loneliness, and it is therefore closely bound in spirit to the place where their story ends. Inis Glora is a tiny island on the west coast of the Mullet peninsula in northwest Mayo. West Mayo is a place of spectacular beauty and spectacular loneliness, and of all its solitary places, the Mullet peninsula is one of the most isolated. The peninsula consists of a long isthmus joined to the mainland by only a thin neck of land. The nearest towns are Castlebar, Westport and Ballina. These towns buzz with people, but none of them is nearer than 50 kilometres (31 miles) away.

The journey from these towns to Belmullet seems even longer than the mileage would indicate because the road takes the traveller through an unrelenting landscape of high mountains, rocky passes, and most of all, blanket bog. This stunning but desolate landscape is barely relieved by a house, much less a village. Boglands have a particular atmosphere which is all their own. No crops can be grown there; no animals can graze there. They contain great riches of plant life but the overriding feeling of travelling through such a landscape is one of desolation. It has a strange, slightly uncomfortable beauty. The bogs are the Irish equivalent of the desert – a desert made up of brown earth and water and open skies; a place in which the individual feels very small against the vastness of a landscape that seems untouched by humanity. The boglands are also preservers – indeed petrifiers of the past, a growing and living memory of the race. When the tracts of bogs at the Céide Fields in Mayo were excavated, extensive remains of a highly organised prehistoric landscape of fields and structures was discovered under the blanket of turf. The dark tower of Bellacorrick power station stands out in harsh contrast to its surrounding bog, the source of its fuel. One wonders if in future years our descendants will look back on the stripping of the bog in the same way that we look back in sadness at the clearing of the great Irish forests.

Perhaps the feeling of loneliness in Mayo is increased by the knowledge that this is not a countryside that was never settled, but one that once had a much higher population than it has now. Mayo was one of the counties that suffered most from the disasters of the nineteenth century, particularly the Great Famine and the ensuing mass emigration. Up until very recently, a huge percentage of its young people were still being leached from its soil. Now, however, the empty landscape is beginning to be filled with new houses – during the past five years, Belmullet has seen growth and prosperity probably unknown since its hey-day as a market town in the mid-nineteenth century. Yet, despite its new wealth, the smells of turf smoke and seaweed still linger in its small harbour.

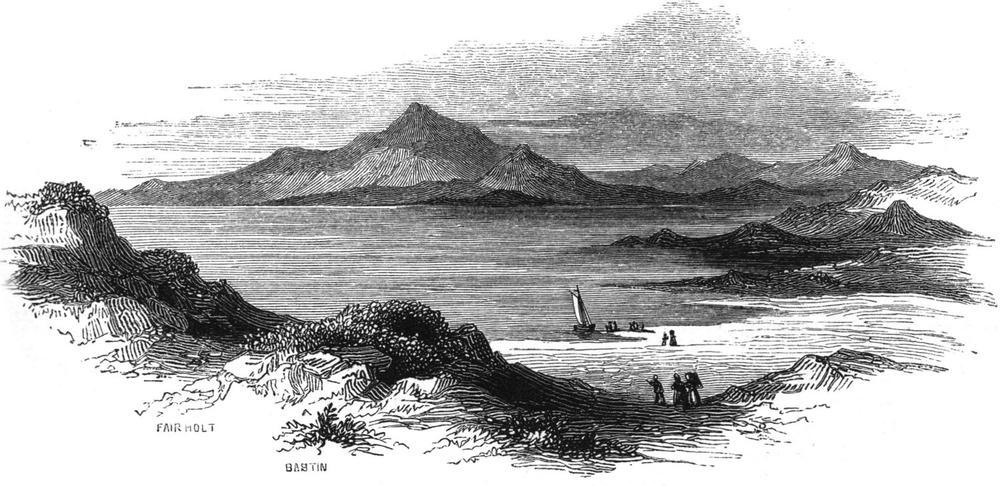

View of Clew Bay and Croagh Patrick, County Mayo, by FW Fairholt.

Inis Glora, however, has lost its human community, possibly forever. Like the neighbouring Iniskea islands, it was inhabited until the mid-1930s, but the island community was shattered in 1927 when ten of its people were drowned at sea. Up until more recently, fishermen lived on the islands during the summer and worked the seas off their coasts, but this too has ceased. There is no regular boat service to Inis Glora, and if you wish to visit it, you must make your arrangements well in advance – it was only the native courtesy and sense of hospitality of the Mayo people which got us there at all.

If you can manage it, make the journey. The island is about 3 kilometres (less than 2 miles) offshore and is only about 27 hectares (66 acres) in size. There is no pier so you would need to be reasonably agile – and wearing wellingtons – for the scramble onto the rocky shore. On the island, there are the remains of a Celtic monastic settlement said to have been founded by St Brendan. You will also find the remnants of a stone church and some beehive huts, together with various other enclosures, including the church of the women. It was said that bodies buried in the soil here did not rot, because the place was so sacred.

The island is deserted now except for sea birds and some sheep. There are no beaches, but lovely golden and pink stones veined with silver line the shore and long ridges from old potato crops, like giants’ graves, cover much of the interior – a record of the lost community. During our visit there, a gull circled noisily overhead, as if warning us off her property. She became particularly vociferous as we walked to the southern end of the island, away from the Christian section. Here there are mounds of broken stone, littered with the bones and feathers of birds, with sheep skulls and brown pools between the rocks. The patterns of the bright tawny lichen on the stones are uncannily like the spirals and semi-spirals, the circles and cup marks of the Megalithic art found at Knowth.

Even if you do not make it to the island, the peninsula itself is a beautiful place to visit. It is covered in extensive early Christian and Megalithic remains. It was the reputed home of Fliodhas, the wife of Fergus Mac Róich and an ancient goddess of wild things, especially deer. The Mullet is a place of long, deserted beaches – pale dunes filled with small singing birds and long grass bending in the wind. In summer, the shades of blue on the distant mountains darken into black and purple; and the lighter greys and silvers also constantly shift and change. These are some of the most beautiful views in Ireland, towards the deceptively gentle line of mountains to the south, with the cliffs and mountains of Achill and the southern coastline of Mayo. Achill is where the great Hawk of Achill, who lived for thousands of years, was said to have had his home. To the south, beyond Achill, is the holy mountain, Croagh Patrick, one of the most revered places in Ireland, where a pilgrimage is still held in July every year – a continuation of the ancient Lughnasa rite. St Patrick is said to have been tormented by black-winged birds on ‘the Reek’, and then comforted by angels with white wings, who came to him in multitudes – one angel for every soul saved in Ireland.

In the townland of Cross on the Mullet, Cross Abbey stands on the coast facing towards Inis Glora at the closest point to the island. Beside a long white beach there are still the remains of a monastery and graveyard. The monks from Inis Glora moved here after they had left the island. Close by, you can visit Cross Lake, which is said to have been a refuge of the Children of Lir during wild winter weather. If you make the journey to the lake in winter, when it becomes the haunt of barnacle geese and whooper swans, you may see white wings flying out towards the lonely island in the west.

THE CHILDREN OF LIR

The moment of transformation – from fair day to storm, from maiden to wife, from good woman to demon, from white-limbed child to swan. Four pairs of grey eyes staring at me in horror as I transformed myself before their very eyes from loving mother into wicked witch. The eyes that looked at me were my sisters’ eyes, and my own eyes, for everyone said that we were as alike as three peas in a pod, the fair daughters of Bodhbh – Aobh, Aoife and Ailbhe. Why did Lir not choose me in the first place? My father offered him the choice; but he chose my elder sister, seeing in her wisdom and nobility.

He did not hear me calling silently to him, ‘Choose me, Prince. Choose me.’

My sister Aobh did not have time to grow old and wise, for she died when she bore her second set of twins, Conn and Fiachra. The eldest pair, Fionnuala and Aodh, were still not much more than babies. And then my father called Lir to him again and offered me to him – Aoife, the second sister, the second best – and he agreed to take me then, but his face and his heart were closed against me.

I loved my husband and I loved my sister’s children, and for many years, I was a good wife and a good mother, while I waited to have my own child – a child to whom I would be the first, the most important one, the real mother. When that did not happen, it seemed that nobody cared very much. Lir had his four children – three sons and a fine daughter – and my father his grandchildren. As they grew up, it seemed that Fionnuala was set to rival my sister in the love she inspired in all who had dealings with her. It is hard to be always second choice. The children made their own self-contained little world: two sets of twins, indissolubly linked, unheeding of my pleas to let me into their tightly closed circle. And that was perhaps why I became bitter and sick, and I lay in my bed for a year and waited for someone to notice. Something grew and hardened in me during that year. Lir would come and ask me how I felt, but did not listen for my answer. Fionnuala would come with the boys, shushing them to be quiet so as not to disturb me. I could hear their relieved laughter when they left me. Life went on around me.

One autumn morning, I got up and called the children to me. I told them that they were going to visit their grandfather, and they were delighted – all but Fionnuala, who looked at me strangely and when I asked her what was the matter, said that she had not slept well, a night of bad dreams.

I took them in my chariot to Lake Derravaragh, and told them to bathe, for although it was the end of the year, the air was mild and the water warm. As I watched them in the water, their white limbs dancing in the low sunlight, splashing and playing and singing and laughing, I knew that I could not kill them. So I took my wand and pronounced their doom, and looked on as the white feathers sprouted on their flesh, their necks growing longer, their feet becoming webbed and their legs short and unwieldy.

‘You shall spend the rest of your days as swans,’ I said. ‘Three hundred years you will spend here at this lake, then three hundred years on the Sea of Moyle. Do you know the Sea of Moyle? It is one of the wildest and coldest seas in the world. Your webbed feet will freeze to the rocks, so that when you try to get loose, you will tear your feet, and when you swim, the salt water will be agony.

The ruins of Cross Abbey standing on the coast, facing towards Inis Glora, County Mayo.

‘The last three hundred years you will spend on Inis Glora, in the western ocean. You shall not be released from this spell until the man of the north marries the woman from the south. But I will give you one boon – during all this time, you will retain your human minds and your human voices, and you will sing such music that all who hear you will be astounded, and however sad they are, they will be comforted.’

And then I could look at them no more, but made my way to my father’s palace. His face dropped when he saw that I was alone, and the bitterness in my heart increased. Of course, it was not long before the people of Danu discovered my evil-doing; and my own father in his great anger turned me into a demon of the air, condemned to fly and wander in exile forever, terrifying all who saw or heard me.

The moment of transformation – from good daughter to shrieking demon, from one of the tribe to the one who will always be an exile. Fionnuala, Aodh, Conn and Fiachra had an easier time of it than I did, for during their three hundred years on the lake, the Danann came and listened to them and cheered them; and their music comforted all who heard it – all, that is, except me. But then they went to the Sea of Moyle, and that was a hard time for them, for the storms beat their soft feathers, and the ice froze their feet to the sharp rocks, and the wind drowned out their singing; and no one was within miles to listen to their music in any case, except poor sailors blown off course who covered their ears for fear of the treacherous songs of mermaids. Fionnuala would try to shelter her brothers under her wings and at the pin-feathers of her breast, and it was only the heat of the four bodies that kept them alive on many, many nights. Often, though, they would be blown apart, separated from each other, and each one found those wild, lonely nights the hardest – not knowing if they would meet again.

How do I know this? I know because I was there, hating them still, but still their mother, watching over them – needing to know that they still suffered. Those wild nights were the only ones where I myself escaped my pain. For, buffeted by wild wind and crashing waves, I was released from the anger that burnt inside me. The wildness of the storms carried me to some other place where I no longer needed love, and my rage was called back to me in the wind and the water.

However, that too finally ended, and the four swans made their way westwards, passing over their father’s sídh at Sídh Fionnachaidh. They called aloud as they passed over, and the Danann looked up at the four magical birds, so white against the blue sky of autumn; they waved at them but the four children did not stop, for the times had changed. The Sídh now disguised their palaces as grassy mounds, hiding them from the eyes of the new race that lived in Ireland. The Place of the White Field seemed to the swans no more than green mounds and furze and crops of nettles – not jewelled palaces and lovely orchards; not houses thatched with white feathers. The song they sang then was so mournful that I think if I had had any heart left, it would have been broken by the music. Meanwhile, below, the Danann called to them in frantic voices to come home, come back to their loved ones. They flew on, unable to hear, far to the west and to the shores of the great ocean.

And there, on Inis Glora, they found a lake on an island, where they made their last home. Their music was such that it drew birds from everywhere around. And after another three hundred years had come and gone, I heard new sounds on the island – the chant of Latin and the tolling of a bell. A hermit came there – a gentle man who listened to the birds every evening, and they told him their tale. He made silver chains for them, which held them together, so that no matter how wild the storms were, they could never become separated. I hid in the trees by the lake, silent and watchful, knowing that the day would finally come when the enchantment would end.

A princess from the south married a prince from the north, and, having heard of the wonderful music of the four swans that lived on Inis Glora, she demanded them as a bridal gift from her husband. But when the prince came to fetch them, the hermit Mochaomhóg refused to give them up. The prince became angry and made to take them by force from where they stood by the altar in the hermit’s tiny church.

And then again, the moment of transformation — from swan to human. Not to godlike children, on the verge of blossoming, but to four withered old people, bent and broken, ready for death – children who had never grown up, had never known the pain of not being loved enough; children who had found love even in the shape of wild swans; children who were nearly a thousand years old.

Then Fionnuala said, in a cracked voice that was hardly above a whisper, ‘Brother Mochaomhóg, our time is not long. Baptise us now, and bury us together in the churchyard of your god. Bury Conn on my right and Fiachra on my left, and place Aodh before me, for it was so we used to stand on the rocks of the Sea of Moyle when the wind buffeted us, during so many cold and bitter nights.’

So the children of the Sídh were transformed into good Christian corpses and buried far from the mounds of their people. The hermit mourned them greatly. He still goes to the lake in the evening, but it is silent now except for the harsh call of the gulls; all the birds that sang there once have fled. My voice has called to him once or twice, but he does not even hear me above his prayers. I continue to live, without the mercy of death. I suffer more than the children ever suffered. They have found release in their last transformation – to bleached bones buried beside a priest’s cell. I am what I have always been. With no hope of rest or change, I make my cries, shrieking my pain over barren islands, limitless oceans, salt foam white as a swan’s wing.