Figure 6.1. (Left) Clairaut (courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Libraries, Washington, D.C.) and (right) his love equation, circa 1745. V is the fixed fulcrum and the i’s and I’s moving clockwise represent the motion of its endpoint.

Further Investigations of the Mind-Body Problem

The Kabbalist: Thinking too much can lead to madness. Don Pedro Velasquez: Reason can accept anything, if it is used knowingly.

—from The Saragossa Manuscript (1965), film by Wojciech Has

The real lover of learning [philomathes] … will not … desist from eros until he lays hold of the nature of each thing in itself with [the rational] part of the soul … drawing near to and having intercourse with the really real.

—Plato, The Republic, 490b.1

If, as French film critic Jean Mitry claimed, “a film is a mirror in which we recognize only what we present to it through what it reflects back to us,”2 do we mathematicians recognize ourselves in the increasingly frequent cinematic images of our profession? When we look in our private mirrors, do we see Carlo Cecchi (Death of a Neapolitan Mathematician), Tilda Swinton (Conceiving Ada), Matt Damon (Good Will Hunting), Gwyneth Paltrow (Proof), Russell Crowe (A Beautiful Mind), Rachel Weisz (Agora), Sean Gullette and Mark Margolis (Pi), David Wenham (The Bank), or Béatrice Dalle (Domaine)? Or perhaps the autistic savants played by Dustin Hoffman (Rain Man) and Andrew Miller (Cube)? Do we agree that we are misfits (Damon, Hoffman, Miller, Dalle, Wenham) if not martyrs (Weisz, Margolis, Cecchi, Swinton), on the verge of madness (Paltrow, Crowe, Gullette, Cecchi) if not over the edge, and stunningly attractive (nearly everyone)?

Now joining the cast is Edward Frenkel, a Berkeley professor and one of the rare mathematicians who would not look out of place on the red carpet at Cannes, as author, codirector, and star of a twenty-six-minute independent film entitled Rites of Love and Math. The action is well summarized by the synopsis included with the film’s press packet:

Mathematics is first and foremost pursuit of Absolute Truth and Beauty. This is the story of a Mathematician who has found, after many years of hard work, the ultimate Formula of Love. At first, he was thrilled that his formula would benefit people, bringing them eternal love, youth and happiness. But later he discovered the flip side of the formula: it could become, if used in the wrong way, a weapon against Humanity. And so forces of Evil are now after the Mathematician. They want to take possession of the magic powers of his formula and misuse them in order to achieve their sinister goals. The Mathematician knows that there is no escape for him, and he is ready to die. But he wants his formula to live.

The Mathematician has a secret love affair with a beautiful Japanese woman, Mariko. At midnight, he comes to her place and tells her about his predicament. Having realized that they are seeing each other for the last time, they make love more passionately than ever before. And then the Mathematician tattoos the magic formula on Mariko’s body. They both know that this is the last time they are seeing each other. Afterward their love will live in this formula engraved on her beautiful body.

Whenever I hear of a mathematician pursuing extraprofessional interests, I am reminded of Claude Levi-Strauss’s impressions of São Paulo high society in the 1930s: “Society, being limited in extent, had allocated various roles to its different members. All the occupations, tastes and interests appropriate to contemporary civilization could be found in it, but each was represented by only a single individual…. There was the Catholic, the Liberal, the Legitimist and the Communist; or, on another level, the gourmet, the book-collector, the pedigree-dog (or -horse) lover….”3 Among contemporary mathematicians, one finds the novelist, the ballroom dancer, the dandy, the cultural critic, the theologian. In recent years Paris has seen a procession of mathematicians from America in novel roles: the installation artist (Benedict Gross), the fashion consultant (the late Bill Thurston), the auteur (Ed Frenkel), and the sex symbol (Frenkel again).

The more dynamic sectors of the French mathematical establishment—represented by the Fondation de Mathématiques de Paris-Centre, which contributed financially to Frenkel’s film, and the Institut Henri Poincaré (IHP), under the direction of the media-friendly Fields Medalist Cédric Villani—have conspicuously welcomed these developments that hint at a kind of glamour to which we are mostly unaccustomed. Although his project suffered neither from corporate sponsorship nor from the support of the mainstream media, turning filmmaker has nevertheless brought Frenkel into some scandalous company, Japanese novelist and ultranationalist Yukio Mishima, for starters. Frenkel’s Rites is consciously modeled on Mishima’s film Yûkoku, also known as Patriotism or The Rite of Love and Death, “suppressed” by his widow after the author performed seppuku in 1970 (according to Wikipedia) until it resurfaced accidentally earlier this century. Through his codirector, the experimental filmmaker Reine Graves, Frenkel was exposed to the psychoanalytic theories of Jacques Lacan—Graves confided to me that Frenkel had read all of Lacan in a single day—as well as to Graves’ former collaborator Jacques Henric, literary contributor to the magazine Art Press, which is directed by his companion, the sexual Stakhanovite Catherine Millet, whose The Sexual Life of Catherine M. is one of the founding documents of what French weekly magazines a few years ago were calling the “new libertinism.” Henric supplied a sort of interpretation for the Rites press kit:

There is also a lesser tradition in literature, philosophy and morals, which strives to ease and even bluntly cut the link between Eros and Thanatos. In the course of the XVIII century, French Libertines followed it, but in the XIX century, with the advent of Romantism [sic],“love to death” came back into fashion, and the past century… did nothing to liberate itself from the influence of this ideology and this moral philosophy. In Japan, on the other hand, a deep-rooted tradition, close in spirit to that of French Libertines, has nourished a grand and steady literary current as well as an essential trend in painting striving to produce the most beautiful images.

Both Mishima’s film and its “homage” by Frenkel and Graves are highly stylized and take place on the Noh stage with Wagner’s Tristan4 playing in the background. Frenkel’s Mathematician, played by Frenkel himself, replaces Mishima’s army officer, who, passionately attached to the emperor as well as to his wife, performs seppuku to avoid being forced to attack his equally patriotic comrades-in-arms. We have seen in the synopsis that the Mathematician impales himself on a blade as well. The ritualized suicides take place after no less ritualized scenes of love-making—“love to death” is alive and well in Japan as well as in Rites—in front of a scroll painting. In Mishima’s film, the scroll reads “Sincerity” in calligraphic Chinese characters; in Frenkel’s it reads Истина [istina], Russian for “truth”—and though the screen informs us that that “In the face of death, the Mathematician and Mariko bid final farewell to every little detail of each other’s body,” what Lacan would have called the Mathematician’s “signifier” remains at all times concealed from the spectator. Here’s Henric again:

What has motivated Edward Frenkel and Reine Graves to make their film Rites of Love and Math? Is it to drive not just the nail, but the knife, if one may say so, between spirit and flesh, or is it to finally reconcile them?

Relatively few professions are practiced even intermittently in the nude, and while Rites is likely to reopen the long overdue debate on whether mathematics, like the fieldwork for Catherine M.’s memoirs, should be one of them, I find the film most explosively scandalous in its confusion of genres—practically a category mistake—focused precisely on the reconciliation Henric evokes of “spirit and flesh,” more classically known as the mind-body problem. Archimedes deserved a best-supporting-role nomination for dramatizing the problem in Plutarch’s Life of Marcellus:

He neglected to eat and drink and took no care of his person; … he was often carried by force to the baths, and when there he would trace geometrical figures in the ashes of the fire, and with his finger draws lines upon his body when it was anointed with oil, being in a state of great ecstasy and divinely possessed by his science [my emphasis].

The Archimedes of classical literature embodies a metaphysical paradox. On the one hand, in the Plutarch quotation, as well as in his Eureka! scene—the most persuasive argument to date in favor of mathematical nudity—he created the classic figure of the mathematician distracted to the point of total withdrawal from the material world, reduced to mind alone. The archetype of the absent-minded mathematician was revived during the Enlightenment, as we see shortly, but is not conspicuous in recent cinematic representations of the profession, and this is perhaps surprising, given that the absent-minded professor is certainly a stock character in popular films. On the other hand, in the familiar anecdotes just recalled, Archimedes’s body is literally visible and uncovered; in a third anecdote, also from Plutarch, a Roman soldier’s sword severed the spirit from the flesh of the Greek mathematician found in a “transport of study and contemplation” on the beach near Syracuse. Seen from the outside, the mathematician’s body is an object of ridicule, inappropriately displayed and in the way. But from the inside the body is irrelevant, at best serving as a convenient surface for the drawing of geometric diagrams, as Mariko’s body in Frenkel’s film is in the end only a surface for preserving Frenkel’s “magic formula”5 or as the bodies in Catherine M.’s narrative, not least her own, are little more than machines performing repetitive and largely predictable motions in a variety of natural and artificial settings.

The scandal of Catherine M. is the “Je” of the first-person narration, told from the viewpoint of one of these machines; the scandal of Archimedes, and of western metaphysics as a whole, is that the mind forever ceases its inventions and discoveries when the body is left in a heap on the sand. An unwritten rule of cinema, especially of erotic cinema, is that not all reminders of materiality are equally painful to behold; in this respect Rites is faithful to the tradition. But attempts to transcend our material limitations and to encompass the infinite within our finite bodies lead invariably to swift retribution and martyrdom: expulsion from the Garden of Eden, the fall of Icarus, crucifixion, or the insanity of the mathematicians represented in popular films. The hero of Pi, having computed the 216-digit number from which all patterns in nature arise, escapes martyrdom only by voluntarily ridding himself, with the help of a power drill, of the substance responsible for his mathematical understanding, located on the border between spirit and flesh in his right temporal lobe.

Members of the nonspecialist public more comfortable with words than images may base their impressions of mathematicians on the biographies, written by distinguished writers and published in Norton’s Great Discoveries series, of Cantor, Gödel, and Alan Turing: two mad-men and a martyr, all damaged by encounters with infinity. Those who prefer a balance of words and pictures can turn to the graphic novel Logicomix, authored by Apostolos Doxiadis and Christos Papadimitriou with a team of professional artists: they will learn that the creators of the logical foundations of mathematics, not excluding the consummate rationalist Bertrand Russell, were haunted by madness. Even those who know only what they see on TV have heard about Grigori Perelman, deemed crazy for turning down a million-dollar prize after having solved “one of the most difficult problems of the last ten centuries” and reportedly slated to be the subject of a James Cameron film.6

Frenkel has explained in a series of press interviews that he wants to “set the record straight” and offer an alternative to the stereotypic image of the mathematician as “the mad scientist” of Pi and A Beautiful Mind:

My purpose is precisely to counter these stereotypes. I wanted the mathematician in our film to be seen as a human being with whom the public can relate: he tries to do his best in difficult times, he is someone who can love and be courageous, who fights for his ideals.7

Once in New York City, near Pi’s neighborhood, a friend’s neighbors, to whom I had been introduced as a mathematician, told me how fortunate they felt to meet someone from such a sensitive profession. In those days, before the dark forces that finance mathematics serves had transformed lower Manhattan’s sociocultural landscape, it was still possible to be moved by a sentiment expressed so unaffectedly, even by a couple marginally integrated into society who, my friend later told me, practiced domestic violence almost on a daily basis. It was the last time artists acknowledged me without prompting as one of their own, and I thought of them at the champagne reception following the film’s first screening, when three of the codirector’s friends, sharing a cigarette, insisted in response to my question that they were not at all shocked to see eros and mathematics treated in film as reflections of one another. On the contrary, although their professionally informed comments were sometimes sharply critical of the lighting, colors, sound, acting—of everything that makes Rites a film rather than an idea, in fact—they were in total agreement that Frenkel and Graves had found a très beau choix de sujet, a beau theme, in conceiving a film about a mathematician who is simultaneously a lover and a martyr to truth.

Reading the blogs, one learns that Frenkel’s complaint about the treatment of mathematicians in popular culture is widely shared. But in an important sense it’s beside the point. Cinema doesn’t need to look to mathematics for unstable or unhappy character types. No one complains that films about Sid Vicious, Kurt Cobain, or Jim Morrison reinforce negative stereotypes about rock musicians, and who can keep track of all the cinematic representations of Van Gogh? The interesting question is not whether mathematicians are portrayed as deranged or tormented, but in what sense their torment or madness is characteristically mathematical.8

Indeed, the madman is only one of the stereotypes on the mathematician’s storyboard. According to historian Amir Alexander,

Among modern mathematicians, it seems, extreme eccentricity, mental illness, and even solitary death are not a matter of random misfortune … in the popular imagination … mathematicians feature prominently as loners and misfits who never find their place in the world.9

Frenkel’s Mathematician is neither a loner nor a misfit, much less a madman, but his death is almost—though not quite—solitary. His film thus reproduces the image of mathematician as romantic hero, the stereotype that, for Alexander, has represented mathematics “in the popular imagination” since Galois was elevated to iconic status several decades after his death. Revisiting the lives of Chopin and the poets Byron, Keats, Shelley, and Novalis—he could have added Pushkin and Lermontov—Alexander sees the romantic hero as “a doomed soul whose quest for the sublime leads to loneliness, alienation, and all too often an early death. But in the few years allotted to him, the romantic hero burns more fiercely and shines brighter than any of his fellows.” Familiar picture, to be sure. More surprising is Alexander’s report that the romantic details of Galois’s biography that have inspired generations of mathematicians—including Frenkel, whose important work on the Langlands program straddles the boundary between Galois theory and mathematical physics—were in large part fabricated in the decades after his death in order to fit Galois into a preexisting romantic mold.10 Moreover, according to Alexander, the “troubled mathematical martyr,” exemplified not only by Galois but also by Abel, János Bolyai, Riemann, Cantor, Gödel, Turing, John Nash, Grothendieck, Perelman, and even, in a certain sense, Cauchy, remains to this day the dominant image of the “ideal mathematician,” long after the romantic paradigm was exhausted in the arts.

Perhaps paradoxically, the well-known account of Galois’ life is the more significant for being false. One sees more clearly that Galois’ invented romantic persona fills and thereby reveals a cultural need; unadorned truth is not always up to the task. Alexander sees this persona as constructed in opposition to the Enlightenment ideal of the mathematician as a “natural man.” The prototype of this ideal, with its obvious echoes of Rousseau, was the mathematician and encyclopedist Jean le Rond d’Alembert, especially as represented by the Marquis de Condorcet in his eulogy of d’Alembert at the Académie Française: another fabrication, as Alexander makes clear. A semifictional d’Alembert was made to play the natural man as “disconnected dreamer and hopeless bumbler” in Denis Diderot’s D’Alembert’s Dream. The “geometer” Don Pedro Velasquez of Jan Potocki’s late enlightenment novel The Saragossa Manuscript offers a more complete and well-rounded fictional interpretation of the mathematician as natural man. Distracted, like Archimedes,11 to the point of walking into a stream while engrossed in his calculations, Velasquez is nonetheless noble and elegant, an engaging storyteller, an enlightened philosopher, and, most importantly for our purposes, an object of romantic interest.

In this respect, the fictional Velasquez was a mathematician of his time. The Oxford English Dictionary informs us that in 1750 “The Wranglers”—top-ranked candidates in the mathematical tripos at Cambridge University—“usually expected, that all the young Ladies of their Acquaintance … should wish them Joy of their Honours.”12 In their obituary dedicated to the analyst and geometer Alexis Clairaut, Diderot and F. M. Grimm recalled the mid-eighteenth-century mathematical craze:

Clairaut avait vu ce règne brillant de la géométrie, où toutes nos femmes brillantes de la cour et de la ville voulaient avoir un géomètre à leur suite. [Clairaut had witnessed the illustrious reign of geometry, when all our brilliant women of the court and the city wanted to have a geometer at their disposal.]13

Figure 6.1. (Left) Clairaut (courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Libraries, Washington, D.C.) and (right) his love equation, circa 1745. V is the fixed fulcrum and the i’s and I’s moving clockwise represent the motion of its endpoint.

Clairaut, who, according to Diderot and Grimm, aimait éperdument le plaisir et les femmes, may have been the first mathematician to propose a love equation [figure 6.1(b)] in the form of the Archimedean spiral, “on which the Geometers have so greatly exerted themselves, without having discovered its true nature.”

On demande la Courbe iiI décrite par l’extrêmité d’un corps Vi, qui étant d’abord dans une situation verticale renversée Vi, change ensuite de grandeur & de position en devenant successivement Vi VI, &c. [We seek the curve described by the endpoint of a body, initially vertical and pointing downward, that subsequently changes in length and position.]14

Enlightenment mathematicians were more likely than not to be erotically curious. In his speculation on life on other worlds, Fontenelle claimed that “mathematical reasoning is made like love” and that “these two sorts of people [mathematicians and lovers] always take more than they are given.” Maupertuis’ thoughts15 on evolution begin with a vivid depiction of the role of pleasure in the preservation of species not unlike the “rites of love” that occupy the middle of Frenkel’s film:

Celle qui l’a charmé s’enflamme du même feu dont il brûle: elle se rend, elle se livre à ses transports; et l’amant heureux parcourt avec rapidité toutes les beautés qui l’ont ébloui: il est déjà parvenu à l’endroit le plus délicieux.

And Potocki, a soldier and adventurer in his early life, has the beautiful and cultivated Rebecca of his novel, in the course of her extended flirtation with Velasquez, ask the geometer where love fits in his system:

Mais, dit Rébecca, ce mouvement que l’on appelle amour, peut-il être soumis au calcul? [But, said Rebecca, this movement we call love, can it be calculated?]

Here on the twentieth day of the narrative,16 Rebecca is concerned with the tendency of a man’s love to diminish with intimacy while the woman’s increases; Velasquez replies that there must, therefore, be an instant when the two love equally and adds, “I have found a very elegant proof for all problems of this kind: let X….” (See figure 6.2.)

On the thirty-third day, Rebecca and Velasquez return to the question with the latter recasting the question in terms of positive and negative numbers:

Si je hais la haine de la haine, je rentre dans les sentiments opposés à l’amour, c’est-à-dire dans les valeurs négatives, tout de même que les cube de moins est moins. [(If I hate the hatred of hatred, I return to the feelings opposed to love, that is to negative values, just as the cube of minus is minus.]

After several paragraphs of this, Rebecca, now called Laure, interrupts Velasquez:

[S]i je vous ai bien compris, l’amour ne saurait être mieux représenté que par le développement des puissances de X moins A beaucoup moindre que X.

Aimable Laure, dit Velasquez, vous avez lu dans ma pensée. Oui, charmante personne, la formule du binôme inventée par le chevalier don Newton doit être notre guide dans l’étude du coeur humain comme dans tous les calculs. [[I]f I have understood you, love is best represented as the development of powers of X minus an A that is much smaller than X.

Figure 6.2. Illustration of Don Pedro Velasquez’ Intermediate Love Theorem. The black curve measures the decline of the man’s love and the gray curve, the increase of the woman’s. The point P is the intersection predicted by Velasquez. Unfortunately, Potocki does not allow his character to present the proof. A more general proof of a similar theorem was first published by Cauchy in his course at the École Polytechnique in 1821, seventeen years after the first edition of Potocki’s book.

Dear Laure, said Velasquez, you have read my mind. Yes, charming person, the binomial formula invented by the knight Don Newton must be our guide in the study of the human heart as in all calculations.]

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

I agree with you quite upon Mathematics too—and must be content to admire them at an incomprehensible distance—always adding them to the catalogue of my regrets—I know that two and two make four—and should be glad to prove it too if I could—though I must say if by any sort of process I could convert two and two into five it would give me much greater pleasure.

—Lord Byron to his wife

Leading mathematicians grew increasingly intimate with power as the Enlightenment waned in the last decades of the eighteenth and first of the nineteenth centuries, and mathematics was prized as a source of charisma. The artillery specialist Choderlos de Laclos, for example, was trained in ballistics—as a mathematician, in other words—before he became known as author of the classic libertine novel Les Liaisons dangéreuses. “Even more than their [Enlightenment] predecessors,” writes Alexander, the mathematicians Gaspard Monge, Pierre-Simon de Laplace, Lazare Carnot, and Joseph Fourier were “men of action, high officials of state under the revolutionary regime and Napoleon, and personal friends of the greatest men of the realm.” And “for [the young Stendhal], at least, mathematics was … the royal road to Paris, glory, high society, women.”17

Readers are nevertheless advised to contain their excitement a bit longer. Since the French revolution literary attitudes toward mathematics have been marked by rejection or indifference, as indicated by the Byron quotation given earlier.18 When Zamyatin’s protagonist D-503 in We asks, “Can I find a formula to express that whirlwind which sweeps out of my soul everything save [his opposite number, the sensual I-330]… when her lips touch mine,” the author clearly wants us to answer: No, there is no formula. Even the economist Francis Ysidro Edgeworth, inventor of the indifference curve, acknowledged in his ambitious attempt to develop a “Hedonical Calculus” of “Feeling, of Pleasure and Pain” that “we cannot number the ‘innumerable smile’ of seas of love.”19

Psychoanalysts did occasionally resort to diagrammatic representations of love, as in Jung’s representation (see figure 6.3) of the archetype of the “marriage quaternio.”20

There have also been bursts of enthusiasm in France. The writer Isidore Isou, who founded Lettrism shortly after World War II and wrote a theoretical and practical study of the “mechanics of women,” as well a treatise entitled Traité d’érotologie mathématique et infinitésimale, devoted a number of texts to formulas for love, including the one illustrated in figure 6.4. Existentialists were more ambivalent, but I have heard of an incident in which one of them caressed the monographs of a well-known mathematician, “the only kind of books they could not understand at all.” Undeterred by their occasional lack of understanding, but deeply influenced by the Bourbaki group’s insistence on the centrality of structures in mathematics, the structuralist generation in France had meanwhile placed mathematical models at the center of their philosophy, with Lévi-Strauss going so far as to include a chapter on group theory by André Weil in his Elementary Structures of Kinship.21 Weil, by the way, is the author of what may be the single most quotable, erotically charged passage on mathematical creation. Attempting to describe how it felt to discover his topological approach to counting solutions to equations, Weil wrote that

Figure 6.4. Formule de l’amour prodigieux, copyright Cathérine Goldstein. I thank her for bringing this image to my attention and for authorizing its reproduction. The formula is accompanied by a legend: A.Pr = amour prodigieux, P = total perfection, p = partial perfection, Per = perversion, D = discussion, M.Er = erotic mechanics, t = time, and so on.

around 1820, mathematicians (Gauss, Abel, Galois, Jacobi) permitted themselves, with anxiety and delight, to be guided by the analogy [between an algebraic and a geometric theory] … [Now] gone are the two theories, their conflicts and their delicious reciprocal reflections, their furtive caresses, their inexplicable quarrels; alas, all is just one theory, whose majestic beauty can no longer excite us. Nothing is more fecund than these slightly adulterous relationships; nothing gives greater pleasure to the connoisseur, whether he participates in it, or even if he is an historian contemplating it retrospectively.22

Among the structuralists, responsibility for love, by way of psychoanalysis, fell to Jacques Lacan, and a flourishing collaboration in Lacanian knot theory remains active at the margins of French mathematics and psychoanalysis. In most of Lacan’s seminars mathematical symbolism made only a fleeting appearance, as in this excerpt, which I will not attempt to translate, from his seminar in Vincennes December 3, 1969.23

JACQUES LACAN—(se tournant vers le tableau). Ça c’est une suite, une suite algébrique…

INTERVENTION—L’homme ne peut pas se résoudre en équation.

JACQUES LACAN—… qui se tient à constituer une chaîne dont le départ est dans cette formule:

Some of the terms in the “algebraic” formula may refer to the poles in the diagram (figure 6.5) of the “mirror stage,” a version of the all-purpose structuralist double binary opposition scheme and the starting point for Lacan’s approach to the mind-body problem, in which “the child anticipates the mastery of his bodily unity by an identification to the image of his likeness and by the perception of his image in a mirror.”24

Figure 6.5. Lacan’s Schéma L: http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sch%C3%A9ma_L.

Interviewed by Daily Californian reporter Samantha Strimling, Frenkel explained “he wanted to challenge the notion of what mathematicians can do” by following Mishima and including a sex scene in Rites:

“How about this: We have a mathematician … who is fighting for his ideas, and he is in love and there is actually a nude scene. He is actually making love to a beautiful woman,” [Frenkel] said. “How about that compared to the stereotypes people are used to?”

I’m not sure I’ve ever met a professor other than Frenkel, in any specialty at any university, who has submitted the surface of his or her body to public inspection in quite this way.25 But we have seen that the fashionable public of Diderot’s time had no doubts about “what mathematicians can do.” It is ironic that the rise of the romantic image of the mathematician coincides with the end of the image of the mathematician as a model romantic partner. George Sand had a full register of romantic men à sa suite, but none of them was a mathematician. Lord Byron’s daughter Ada, in contrast, was encouraged by her mother to study mathematics expressly in order to protect her from her father’s romantic madness.26 Every mathematician knows that Galois was killed in a duel over a woman—sometimes identified as “Stéphanie”—but Alexander argues that “the affair, such as it was, did not go well, and […] Stéphanie was trying to distance herself from the intense young mathematician.”

Figure 6.6. His and hers matching love formulas: from the short film Riducimi in forma canonica [Reduce me to canonical form] by Monica Petracci, 2000.

Galois’ death, for Alexander, was the culmination of a pattern of ar-rogant and self-destructive behavior rationalized as uncompromising devotion to the truth. In the letter he addressed “to all republicans” on the eve of his death, Galois can only “repent having told a baneful truth to men who were so little able to listen to it calmly … I take with me to the grave a conscience clear of lies.”27 Alexander argues that the transition from the Enlightenment to the romantic ideal in the lives of mathematicians parallels a transformation of the subject matter. “… [T]he new mathematicians turned away from the Enlightenment focus on analyzing the natural world to create their own higher reality—a land of truth and beauty governed solely by the purest mathematical laws.”28 In his own mind and in the legend that grew up around his life, Galois died for the sake of what Rites’ synopsis called “Absolute Truth and Beauty,” just as Frenkel’s Mathematician died for istina. But where, as Alexander continued, “[the romantic], whether poet, artist, or mathematician … was … an otherworldly creature who belonged in a better and truer world than ours,” the Mathematician of Rites devotes his life’s work to discovering a “Formula of Love” that “would benefit people, bringing them eternal love, youth and happiness.”29 Is Frenkel’s Mathematician’s romantic martyrdom for truth in contradiction with his materialist objectives, like the Enlightenment practitioners of mathematics as a “science of the world that had its roots planted firmly in material reality”?30 Or do Frenkel and Graves agree with the Russian mathematician A. N. Parshin, who wrote, referring to the mathematics of elementary particles, that “The deeper we plunge into the material world, the further we move from it in the direction of the ideal world”?31

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Hal: […] Mathematicians are insane. I went to this conference […] last fall. I’m young, right? I’m in shape. I thought I could hang out with the big boys. Wrong. I’ve never been so exhausted in my life. Forty-eight straight hours of partying, drinking, drugs, papers, lectures …

Catherine: Drugs?

Hal: Yeah. Amphetamines mostly. […] Some of the older guys are really hooked. […] They think math’s a young man’s game. Speed keeps them racing, makes them feel sharp. There’s this fear that your creativity peaks around twenty-three and it’s all downhill from there. Once you hit fifty it’s over, you might as well teach high school.32

A totally unfounded fantasy, and if you were expecting any serious gossip at this point, I’m afraid you’re going to be disappointed. On the contrary, there seems to be a growing consensus that, in spite of the persistent public fascination with mathematics, it’s not among mathematicians that you’ll find the best parties and that life is more fun in the company of dancers, philosophers (Anglo-American or continental), hedge-fund managers, fashion designers, biomedical engineers, theater critics and/or performers, historians, industrialists, Russian Orthodox theologians, or anyone involved with the movies. In the new world of public-private partnerships, leading European research institutions are also encouraged to follow the dark side into its realm of dream and magic. Consorting with the men and women at the summit of the socio-economic firmament is consistent with the injunction raining down on us from all quarters to tie our work more closely to the needs of production, especially the production of wealth. The culture industry, meanwhile, deals primarily in the production of novelty, and indications are that the added value of mathematics, as a cultural signifier of indeterminate scope, has yet to be exhausted. Aronovsky’s Pi, whose plot is driven by Wall Street’s search for a (deterministic) formula to predict the future course of stock prices, stands as a reminder that the “forces of Evil” will not invest in our work without expecting a substantial return. When a mathematical community still largely faithful to the romantic ideal crosses paths with the masterminds of enlightened materialist ruthlessness, will the result be a second Enlightenment mind-body synthesis, a Faustian bargain signaling a renewed appreciation of one another’s desirability, with the “brilliant women of the court” replaced in the updated version by shapers of taste and prophets of economic competition, and with the reflection on human freedom of a Rousseau or a Condorcet replaced by obsessive attention to the bottom line?

In recent years, mathematics has made its mark on the inexhaustible witches’ sabbath that is Paris nightlife. Harvard mathematician Benedict Gross passed through Paris in the fall of 2008 for the opening of his collaborative installation with multimedia artist Ryoji Ikeda at Le Laboratoire, a “creative space” near the French Ministry of Culture “dedicated to experimental collaboration between artists and scientists,” directed by the author and biomedical engineer David Edwards. After exchanging messages for a year on “mathematics, infinity, the sublime,”33 Gross and Ikeda settled on an installation of two horizontal monoliths, each covered with more than seven million tiny digits representing in one case a prime number, in the other a “random” number.

Biomedical engineers have the edge on parties, if the opening reception at Le Laboratoire is any indication. Wandering across the dimly lit exhibition space—the two numbers were illuminated from above and their digits could be inspected only with the help of a magnifying glass—the few mathematicians in attendance, Ed Frenkel and I among them, gradually found one another in a crowd of hundreds of the experimental collaboration’s boisterous and exuberantly stylish celebrants. An office door slid open before us, and we were ushered in to join the collaborators. While Edwards fiddled with a magnum of VIP champagne, Ikeda dropped to his knees at the feet of Jean-Pierre Serre and announced, “For me you are a rock star!”

Figure 6.7. Thurston and assistant wrapping Dai Fujiwara in a knot (my photo); still from http://www.isseymiyake.com/isseymiyake_women/ (photo Frédérique Dumou-lin/Issey Miyake).

Parisian mathematics had no official representation at Le Laboratoire but was in evidence at the March 2010 opening of another Japanese-American collaboration, this time between the late topologist Bill Thurston and Dai Fujiwara, creative director for the Issey Miyake fashion house.

“[Y]ou did not need a top grade in math to understand the fundamentals of this thought-provoking Issey Miyake show….”34 Fujiwara had contacted Thurston after learning about Thurston’s Geometrization Conjecture and its connection with the Poincaré Conjecture. Fashion designer and mathematician, it turned out, both used the peeling of an orange to help their students understand geometry. “We are both trying to grasp the world in three dimensions,” Thurston told the AP. “Under the surface, we struggle with the same issue.”35

Alerted by a message from IHP director Villani (who starred as himself in the 2013 film Comment j’ai detesté les maths—we’ve seen his own fashion statements favor a nineteenth-century romanticism), my colleagues and I arrived in time to sample the hors d’oeuvres (American and topological: doughnuts, pretzels, bagels) and to register the shocked expressions of the insiders, too spontaneous to be concealed, as they witnessed the breaching of a fortress of Parisian fashion by the hopelessly unfashionable. Thurston (the “coolest math whiz on the planet,” according to an admirer of his YouTube appearance36 with Fujiwara) modeled an original Miyake blazer created for the occasion at the show and again at the reception. Playing neither the natural man nor the romantic hero (“I can’t believe this mathematics guy. He’s so … not like what I expected.”), Thurston told his interviewer that “Mathematics and design are both expressions of the human creative spirit.”37

Like the authors of Rites, Thurston invoked truth and beauty in his essay for the show. “The best mathematics uses the whole mind,” he insisted, “embraces human sensibility, and is not at all limited to the small portion of our brains that calculates and manipulates with symbols.” Thurston was back in Paris in June 2010 for the ceremony organized by the Clay Mathematics Institute to honor Grigori Perelman for his solution to the Poincaré and Thurston conjectures. A grandson of Poincaré was on hand, and the pantheon of the last fifty years of geometry, with only a few notable exceptions, had been assembled for the occasion, which was extensively covered by the French media (though not more than the Laboratoire show). One by one, the distinguished senior geometers stood up to praise the absent Perelman, who had not yet decided to refuse the Clay Institute’s million dollars. Only Thurston took the opportunity to express sympathy for Perelman’s defense of the romantic ideal against the onslaughts of the good intentions of megaloprepeia:

Perelman’s aversion to public spectacle and to riches is mystifying to many…. I want to say I have complete empathy and admiration for his inner strength and clarity, to be able to know and hold true to himself. Our true needs are deeper—yet in our modern society most of us reflexively and relentlessly pursue wealth, consumer goods and admiration. We have learned from Perelman’s mathematics. Perhaps we should also pause to reflect on ourselves and learn from Perelman’s attitude toward life.38

Most of the spectators at Rites’ first screening were artists of some sort, rather than mathematicians, and were apparently drawn from Reine Graves’ extensive list of Facebook friends. Once again, it was not hard to identify the mathematicians in the crowd at the postscreening reception, but the contrast was not as jarring as at Thurston’s fashion show. On the contrary, the champagne was a democratic vintage and everyone in the Rites audience seemed to share a rejection of the couture mindset—the artists by design, the mathematicians by indifference. Communication across the cultural divide was cryptic but unstrained. One of Graves’ three friends speculated that les maths sont là pour exprimer l’essence de la nature [the math is (in the film) to express the essence of nature]; another saw une beauté calligraphique [a calligraphic beauty], analogous to the calligraphy at the center of the Noh stage, in the tattooed Frenkel-Losev-Nekrasov formula. Number theorist Loïc Merel, on the other hand, thought the film was an exploration of “how to preserve knowledge” but that the question was not taken seriously; the film’s language was that of a conte de fées [fairy tale].

To mark the conclusion of a year spent in Paris as the occupant of the Chaire d’Excellence de la Fondation Sciences Mathématiques de Paris, Frenkel organized a mathematical conference entitled Symmetry, Duality, and Cinema at the Institut Henri Poincaré. Four lectures on mathematical topics of interest to Frenkel were followed by another projection of Rites d’Amour et de Math. At the champagne reception that followed,39 I took notes while Gaël Octavia, the Fondation’s public relations specialist, asked Graves why she decided to make a film about mathematics.40 Without hesitating, Graves, whose motto is ne jamais avouer [never confess], gave the very best possible answer. Mathematics, she began, is un des derniers domaines où il y a une vraie passion [one of the last areas where there is a genuine passion]. Cinema, according to Graves, is dominated by economics; so is contemporary art. Mathematics, like a very few other activities—she mentioned physics and sculpture—is practiced without complacency [sans autosatisfaction]; instead there is a true exigence au travail [demanding work ethic]. Mathematicians seek to percer le mystère. You can see it at once in l’oeil qui brille [the eye that gleams].

Let us gaze back a moment into the gleaming mathematical eye that Graves finds so compelling. Amir Alexander describes a portrait of Abel by the Norwegian painter Johan Gørbitz:

[I]t is the young man’s eyes that grab our attention and draw us irresistibly toward them. Dark and intense, … [t]hey burn with a fire that suggests deep passions of the soul and profound insights of the mind. Their gaze shoots out from the painting’s surface … focused not on us but on a distant point on the horizon … the portrait is of a man … absorbed by his own inner flame and a vision he perceives far beyond.41

And looking back at us from romanticism’s troubled borderlands, the eyes of Pechorin, Lermontov’s Hero of Our Time, “shone with a kind of phosphorescent gleam … which was not the reflection of a fervid soul or of a playful fancy, but a glitter like to that of smooth steel, blinding but cold.”

Alexander’s final chapter compares the portraits of Abel and Galois to the self-portraits of early romantic painters A. Abel de Pujol and O. Runge, as well as to contemporary portraits of Keats and Byron—always the same “oeil qui brille.” In contrast, enlightenment mathematicians like D’Alembert and Johann Bernoulli resembled nineteenth-century physicists like Helmholtz and Lord Kelvin, “successful men of the world, showing no hint of the morose sentimentality that became a hallmark of the [romantic] mathematical persona” (pp. 260–61).

“In the film that [Frenkel and Graves] envisioned.” writes Henric,

the central character … fights not for honor [in contrast to Mishima’s hero, M.H.], but, like his ancestors in science and philosophy, for truth. So here is the question, philosophical, religious, political, moral: should one sacrifice himself and die for the truth?

Yes, said Socrates, Giordano Bruno, Michel Servet …, and all scholars and thinkers who did not compromise with the truth and preferred death to disowning it. No, said the philosopher Kierkegaard.

In his own mind, Galois had no doubt that he belonged to the first group. Stripped and doomed like a gladiator, Frenkel’s Mathematician is a martyr following in the footsteps of Galois or Socrates … or of Hypatia of Alexandria, the third mathematician, with Archimedes and Frenkel, whose biography features a prominent nude scene. Along with another entirely gratuitous nude scene, this one, culminating in her martyrdom, is duly included in Alejandro Amenabar’s film Agora, starring Rachel Weisz as the scientist and philospher of late antiquity. Amenabar’s depiction of Hypatia’s murder is lighthearted in comparison with Gibbon’s version, in which the crowd literally inserts the knife between the victim’s spirit and mortal flesh as if to punish the latter for its pre-sumptuous affirmation of its primacy:

On a fatal day, in the holy season of Lent, Hypatia was torn from her chariot, stripped naked, dragged to the church, and inhumanly butchered by the hands of Peter the Reader and a troop of savage and merciless fanatics: her flesh was scraped from her bones with sharp oyster-shells and her quivering limbs were delivered to the flames (Gibbon, Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Chapter XLVII).

It hardly matters that there is no basis in the scanty historical record for the film’s contention that Hypatia died for her defense of scientific rationalism in the face of religious fanaticism.42 On the contrary, as with Alexander’s deconstructive reading of the Galois legend, Amenabar’s film is less interesting for its history of Hypatia than for what it tells us about our cultural moment: that we need a martyr to truth and beauty, or to the “science et []amour” of Leconte de Lisle’s 1847 poem Hypatie. The following verses could serve as a point-by-point illustration of Alexander’s characterization of the mathematician “absorbed by [her] own inner flame and a vision [she] perceives far beyond”:

Sans effleurer jamais ta robe immaculée,

les souillures du siècle ont respecté tes mains:

tu marchais, l’oeil tourné vers la vie étoilée,

ignorante des maux et des crimes humains.

L’ homme en son cours fougueux t’a frappée et maudite,

mais tu tombas plus grande! *

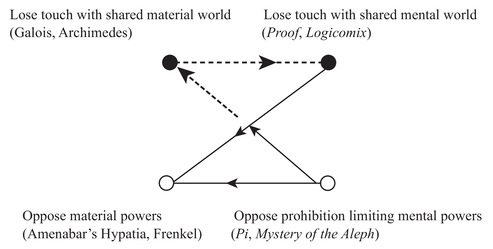

There is a kind of satisfying symmetry that helps us understand what is peculiar about mathematical madness as it appears in the wider culture. Those mathematicians who turn their eye, gleaming or otherwise, to the “starry life,” neglecting the material world, are martyred in the flesh like the Hypatie of Leconte de Lisle’s poem, or like Archimedes or Galois, victims of their devotion to their science. Those who assert the primacy of the human mind, like Amenabar’s Hypatia, or of the individual mind, like Frenkel’s Mathematician, are again martyred in the flesh, victims this time of the “forces of Evil” that seek to extend their control over the material world. Madness, on the other hand, is martyrdom in the spirit, the fate of mathematicians who focus their minds too closely on what must remain unseen, like the protagonists of Pi or the Georg Cantor in Amir Aczel’s The Mystery of the Aleph,43 or who pursue their intuitions so far into abstraction that they cannot find their way back, like the Gweneth Paltrow character’s father in Proof or Cantor (again) in Logicomix. With a bit of imagination, we can even squeeze these alternatives back into that handy structuralist double binary opposition scheme, as follows:

Figure 6.8. Hypatia turning her eyes to the “starry life.” The image appears in Kids Britannica online and elsewhere (Photos.com/Thinkstock).

But there is also a persistent asymmetry that brings us back to the scandal with which this essay began, insofar as it is possible to lose one’s mind while one’s body remains intact, while profane history records no instance of the reverse … except perhaps when the spectator identifies with the martyred characters on screen:

[T]he spectator is absent from the screen. He cannot identify to himself as object…. In this sense, the screen is not a mirror. But this other whom he observes and hears in the film is a psychic prosthesis, an imitation with which it is possible to identify.44

In western metaphysics, the specialist in survival of the spirit despite martyrdom in the flesh is Jesus, who famously declared, “I am truth.” In the Greek of John 14:6, the word for truth is aletheia, translated into Russian as istina. This is how the word becomes central to Russian Orthodox theology.45 Readers familiar with pravda as the Russian word for “truth” may have been wondering why Frenkel instead chose the word istina for the icon hanging beside Mariko’s futon. The answer is that the two terms have different roots, with pravda in the semantic complex, including the words for law, justice, and rules, while istina carries the sense of the adjective istinnii, genuine; thus in Lermontov’s novel, Pechorin’s lover could write “no one can be so truly [istinno] unhappy as you, because no one endeavors so earnestly to convince himself of the contrary.” The pravednik is the righteous man one occasionally encounters in the Bible, but we have seen that istina is the religious truth Jesus claims to embody; istina is also the technical word for mathematical truth, as in Gödel’s theorem. Here’s Maria Kuruskina’s advice, on the AllExperts Web site, for those of you wondering which word to choose for your next tattoo:

‘Istina’ is a great deal more pathetic and I’d say lofty or elevated than ‘pravda’. In sentences like “Neo, you’re the One because you know the Truth” … Russians would use ‘istina’.

‘Pravda’ is neutral. It’s used in phrases like “you must tell me the truth”. For a tattoo i’d recommend ‘istina’.46

What survives Frenkel’s martyrdom is his formula, istina, tattooed above his lover’s47 womb. I will resist the temptation to read this as a promise of the mathematician’s spiritual reincarnation and will instead turn to the practical, cinematic, and theological question of how mathematical truth can burst into our lives with the devastating consequences illustrated in Rites.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

The true (istinniy) artist does not want his own truth, whatever the cost, but rather the beautiful, objectively beautiful, that is the artistically incarnated truth (istina) of things…. If the truth is there, then the work establishes its own value. (Pavel Florensky)48

I have never consciously attempted to find an equation for love, nor have I knowingly appeared in a movie. But in preparing this chapter, I learned that my namesake, the actor Michael Harris, starred as the evil half of a pair of identical twins in the film Suture, described as a meditation on mind-body duality and featuring a plastic surgeon named Renée Descartes. And on numerous occasions during the feverish year when I wrote my PhD thesis, I woke up vainly trying to recall the formula or the diagram that in my dream had solved one of my many pressing material problems, often with love as primary focus.

Presenting his film at the IHP, Frenkel confirmed Merel’s intuition, saying that the film had been conceived as an “allegory” and a “fairy tale.” That may be accurate as a description of the film’s tone, but not of its narrative arc: a typical (Russian) fairy tale has a thirty-one-part structure, according to Vladimir Propp’s classic study Morphology of the Folktale, and usually a happy ending to boot. Nor, the Liebestod notwithstanding, is Rites of Love and Math a tragic romance on the model of Tristan and Isolde. In Mishima’s Yûkoku, Reiko announces to her officer “I know how you feel, and I will follow you wherever you go,” and she keeps her word, dying over the beloved warrior’s body, as Isolde did before her. No such symmetrical closure concludes Rites. Condemned as a sort of human parchment to outlive her fallen lover, Mariko must maintain her mind as a shrine to the lost Mathematician while her body preserves the fatal formula for eternity. Frenkel’s second cinematic venture, a screenplay with Thomas Farber entitled “The Two-Body Problem,” promises a parade of women in bikinis as a “visual trope,”49 but the inconveniently tattooed Mariko will never be among them.

Attempts to reconcile the plot with what life has taught me about the material world confronted my mind with unwelcome questions. The Mathematician’s mind is safely beyond the reach of the “forces of Evil,” but how will Mariko, her skin still stinging from the pain of the tattoo needle, dispose of his body without attracting their attention? Because the Mathematician “wants his formula to live,” Mariko has consented to keeping her own body healthy, her skin taut, forever; but how will she explain the formula to her doctor? And what will she tell them at the gym?

Focusing on such questions to fill in gaps in limited information, a precious logical skill in the hands of mathematical crime fighter David Krumholtz in the TV show Numb3rs or of Elijah Wood and John Hurt in the film The Oxford Murders,50 is useless in the face of allegory and totally inappropriate on the Noh stage. But if love in Rites is to be more than a symbol, a four-letter word illustrated in red and gold and conventional iconography, the viewer cannot help wondering how the equation is actually supposed to work. Eugene Wigner’s canonical version of the mind-body problem concerns “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences”; mathematics stands at the mental pole of the antinomy, the universe at that of the body. What troubles me is this: how am I supposed to understand the unreasonable erotic effectiveness of the Frenkel-Losev-Nekrasov love equation?51

Setting aside the odd interpretation on the Russian website Woman Today,

[i]t is fully realistic, according to Frenkel, to predict life expectancy precisely, if you have at your disposal the statistics of a person’s sexual acts.52

I ask: are the equation’s “magic powers” like the magic formulas in Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus?

The iterating of these lines brings gold;

The framing of this circle on the ground

Brings whirlwinds, tempests, thunder and lightning;

Pronounce this thrice devoutly to thyself,

And men in armour shall appear to thee,

Ready to execute what thou desir`st (Mephistopheles to Faust, Scene V).

Does the love formula bring new love into being or reveal existing love that is concealed? Is it actually a sex formula and can it, like a date-rape drug, force “love” on the unwilling? Or is that one of the “sinister goals” of the forces of Evil? Is the Frenkel-Losev-Nekrasov equation of figure 6.9 a record postfacto that explains how your seductions fit into a pre-ordained order, like Pasolini’s Teorema? Or is it the profane translation of a “Let there be love!” from an alternative Scripture? And does it act on minds, or bodies, or both? Does it act on all bodies or minds at once or on a few at a time? (And in that case, how many bodies and how many minds?)

Writing having stalled while I puzzled over these questions, I sent a partial draft to Amir Alexander, who wrote back suggesting I read Frenkel’s character not as one of the archetypes of Alexander’s book but rather as a “classical Renaissance magus,” like Dr. Faustus. “A magus is a manipulator of abstract signs, … not for their own sake (as is the case for the romantics) but rather for earthly power. He may use it for the good, as Frenkel’s hero hopes to do, but his power is always suspect….”

Before he became a filmmaker, Ed Frenkel was known as a brilliant product of the incomparable Moscow mathematical school53—one of the last mathematicians to be trained in that school before it broke up, along with the Soviet Union, when many of the best-known Russian mathematicians left for Europe, Israel, and (especially) North America. In their important book Naming Infinity, Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor trace the rise of Moscow mathematics to the influence of the Russian Orthodox doctrine of name worshipping [imyaslavie], whose theology and religious practice are based on the postulate that “The name of God is God Himself.”54 Treated as a heretical sect by the Orthodox hierarchy and persecuted by Soviet authorities, the name worshippers included Dmitri Egorov and Nikolai Luzin, considered by Graham and Kantor to be the founders of the Moscow school, as well as their colleague, the mathematician, engineer, philosopher, Orthodox theologian (and priest)—and political martyr55—Pavel Florensky.

Figure 6.9. The Frenkel-Losev-Nekrasov Love Equation, conscious (from Frenkel et al. 2011). For the embodied version, see the trailer to Rites of Love and Math, http://vimeo.com/15492339, 1′44″.

Just as the name worshippers believed that the repetition of the name of God in the Jesus prayer would bring them into the presence of God, the Moscow mathematicians, according to Graham and Kantor, maintained that mathematical objects were brought into being in the course of giving them names. It would appear from this description that name worshipping goes further in breaking through the mind-body barrier than mathematics, whose naming process remains on the mental side. But Moscow mathematician A. N. Parshin, a contemporary interpreter of Florensky, views both word and meaning in purely mental terms:

[T]he meaning of a word represents itself as a wave of (intelligible) light, located in supersensible space…. the perception of a word is not merely connected to the perception of light, it is the perception of light, but a mental light.

And

vision arises from the sense of touch. Florensky liked this idea very much. The primary sense, the primary mode of knowledge, is touch of the surface, while vision is touch by means of the retina…. we may conclude that reflection in the act of knowing takes place by means of reflection with respect to the surface of the body, that is all the surface of the body is a mirror.56

The name worshippers pronounced the name of God—many more times than thrice—not for earthly power but to bring about a spiritual experience. The Moscow mathematicians went beyond manipulation of their abstract signs by giving them names. The theory behind the “love equation” is analogous: invocation of the formula suffices to bring “eternal love” (as well as youth and happiness).

From this perspective, Rites is not a fairy tale but rather an allegorical expression of theological mysticism. But everything about the film’s imagery suggests that its sphere of action is not limited to the mind but, like the Faust legend, encompasses the realm of the senses in its full materiality, not merely the realm of mental perception to which Parshin alludes. Is this the transgression for which Frenkel’s Mathematician must pay with his life? Or are the filmmakers reaffirming the principle the Abbé Suger had inscribed on the doors of the Basilica of St. Denis?

Mens hebes ad verum per materialia surgit

[The dull mind rises to truth through that which is material.]57

Florensky challenges our dull minds with a series of cryptic definitions of the body. Each definition illuminates a different aspect of the mind-body problem while reinforcing Parshin’s conception of the body as mirror: “The body is the most spiritualized substance and the least active spirit, but only as a first approximation.” “The body is the realization of the threshold of consciousness.” “The body is a film that separates the region of phenomena from that of noumena.”58 Of particular relevance to Rites is the following:

That which is beyond the body, on the other side of the skin, is the same striving for self-revelation, but hidden to consciousness; that which is on this side of the skin is the immediate presence of the spirit, and thus not extended beyond the body. In being conscious, we clothe ourselves [literally “robe,” as in the church], and ceasing to be conscious, we lay ourselves bare.59

The passage is obscure, but I will risk a possible interpretation. Parshin has written that “reflection with respect to” the mirror that is the surface of the body “exchanges the internal and the external.”60 Florensky seems to be saying that when we are (figuratively speaking) dressed, the surface of the body acts as in Parshin’s model, exchanging the region of noumena—the intelligible [umopostigaemii]—with that of phenomena—the sensual [chuvstvennii], both of which are located within the mind; this is what it means to be conscious. And when we’re undressed—well, when consciousness is absent—the body is doing its thing, and who knows what that’s about?

I mean, who really knows?61 Who can know well enough to express it all in a formula? Maybe what the existentialists couldn’t understand in the monographs they caressed was what their formulas and arcane language had to do with human freedom, responsibility, and desire. Lacan’s heckler was right: “L’homme ne peut pas se résoudre en équation [man cannot be expressed in an equation].” Nor could that couple in figure 6.6 really be reduced to canonical form. At least that’s what Florensky thought. Writing about love, he explains what he sees as Spinoza’s category mistake (not so different from the category mistake in philosophy of Mathematics):

For love is directed toward a person, whereas desire is directed toward a thing. But the rationalistic understanding of life does not distinguish … between a person and a thing … it has only one category, the category of thingness, and therefore all things, including persons, are reified by this understanding, are taken as a thing, as res.62

You might say—and you would hardly be the first to say it (see chapter 8)—that love, as a subjective experience, is exactly what cannot be expressed in a formula. That’s what makes it subjective rather than a variant of “thingness.” The body can be tattooed from head to foot with an owner’s manual, rules for operation (pravila expluatatsii) sent down from the mental heavens, but neither alone nor in combination will they produce the experience of true love (istinnaya lyubov’) that springs out with our bodies from the earth. Frenkel’s Mathematician’s Ultimate Formula of Love, subordinating the body to the calculating mind, can work only by means of a category mistake. In other words, it can’t work. And that’s why the Mathematician has to die. Otherwise no one would ever believe it possibly could have worked!

Florensky saw not only love but also the relation to truth [istina] as essentially personal. “Christ said: I am Truth,” Parshin explained to me; “the truth is a personality, not a mere object.” In Florensky’s philosophy, “an act of knowledge is a communication or relation, even a kind of ‘friendship’ between the two persons, the one who studies and the one who is studied.” For pure mathematicians in the romantic mold, Parshin’s mirror model—physical reality as mediation between sensual experience and the intelligible world, our gleaming eyes turned, like Hypatie’s, toward the stars, there to find the “land of truth and beauty” of which Alexander wrote—seems just about right. The mirror is mirrored by the words of Simon McBurney, director of London’s Théâtre de Complicité, explaining how mathematics works as a metaphor for love when no formula is possible:“Infinity is a way to describe the incomprehensible to the human mind…. In a way it notates a mystery. That kind of mystery exists in relationships. A lifetime is not enough to know someone else. It provides a brief glimpse.”63

Goethe reincarnated the magus Faust as a romantic hero, as Mephistopheles was well aware:

Fate hath endow’d him with an ardent mind,

Which unrestrain’d still presses on for ever,

And whose precipitate endeavour

Earth’s joys o’erleaping, leaveth them behind.*

And though Faust eventually died, his Truth survived him, and the angels cheated Mephistopheles of his soul:

Those that damn themselves,

be healed by Truth;

so that from Evil

They gladly release themselves.†64

Sometimes I think the whole mad/martyr/mathematician angle is a ruse to trick the forces of Evil, to cheat the boardroom Mephistopheles who are skeptical that our efforts will bring them tangible returns. Our readiness to sacrifice our minds and bodies to our vocation is the ultimate proof that what we are doing is important, even if—as far as any observer can see—we never leave our side of the mirror.

P. A.: Are you deliberately trying to be thick?

N. T.: How nice of you to stop by! But I’m afraid I have no idea what you are talking about.

P. A.: Frenkel is not claiming his formula actually induces or explains or calculates love in any way. It’s a metaphor, silly. As Florensky might have said, his “act of knowledge” is a kind of “friendship” between the mathematician and his formula. The feeling of the mathematician about his formula is analogous to the feeling of love.

N. T.: Aha! So Frenkel is saying that mathematics feels like love. Are you convinced?65

P. A.: At least in both cases there is a feeling of transcendence of one’s state as an individual. That’s why love is described as an out-of-body experience. The proof is that I can represent love on the stage to people who are not bodily present.

N. T.: Now you’re trying to compete with me in paradox. Frenkel did feel compelled to represent bodies on the screen.

P. A.: And you felt compelled to write more than was strictly necessary about those bodies. We should agree that you can have an out-of-body experience only if you have a body to begin with.

N. T.: Just as you need a mind to go out of if that’s where you intend to go.66

P. A.: That’s just the challenge mathematicians have lately been posing to performing artists, to represent a personality, perhaps with an exaggerated work ethic, but otherwise totally nondescript, on the verge of insanity.

N. T.: From what I’ve heard, it shouldn’t be such a challenge for a performing artist to impersonate a borderline personality. But since you brought it up, you might be interested to know that transcendence is also amenable to mathematical analysis.

P. A.: I suspect you are trying to reassert your seniority in matters of paradox. For me, the transcendent is precisely whatever escapes rational analysis of any kind. As Levinas wrote, for example, “the idea of infinity is a thought which at every moment thinks more than it thinks.”67

N. T.: Be patient; then you can decide whether or not your transcendence and mine have any hope of making contact.

P. A.: It would have been pointless to have gone out of my way at such an hour if there were no hope at all.

N. T.: If that’s how you feel, we should get your disappointment out of the way immediately. As far as I can tell, there is exactly one transcendence theory, which as it happens is a branch of number theory. But let me switch off the lights and I’ll go back to the big screen.

* “Never brushing your immaculate robe / the century’s stains respected your hands / you walked, your eye turned to the starry life/ignorant of human evils and crimes / Man in his impetuous course struck and cursed you / but you fell all the greater!” Hypatie, Leconte de Lisle.

* Ihm hat das Schicksal einen Geist gegeben,

Der ungebändigt immer vorwärts dringt,

Und dessen übereiltes Streben

Der Erde Freuden überspringt.

† Die sich verdammen,

Heile die Wahrheit;

Daß sie vom Bösen

Froh sich erlösen.

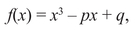

chapter β.5

How to Explain Number Theory at a Dinner Party

IMPROMPTU MINISESSION: TRANSCENDENTAL NUMBERS

We have been talking about roots of polynomial equations, and I think you are now willing to admit that the root of a polynomial f(x) is an answer to a question about numbers and is, therefore, a number. For example, if

then the question

For what α is f(α) = 0?

has three answers. You remember we gave formulas for these answers and called them Olga, Masha, and Irina. You also remember that there is usually no formula when f is a polynomial of degree 5 or more; nevertheless, the roots are answers to a question similar to the one we just considered and, therefore, are numbers. According to the terminology that goes back to Leibniz, roots of polynomial equations are called algebraic numbers; all the other numbers are called transcendental numbers, and transcendence theory is the study of transcendental numbers.

The first obvious question is this:

Question 1: Are there any transcendental numbers?

The first transcendental number was exhibited by Joseph Liouville in 1844; it was a number λ he concocted for just that purpose, but it answers Question 1 and, therefore, certainly qualifies as a number. When I say Liouville “exhibited” the number, I mean that he wrote down a description and used this description to show (very ingeniously) that there is no polynomial f for which f(λ) = 0.

If all transcendental numbers were as artificial as Liouville’s λ, transcendence would never have grown into a mathematical theory. Methods were soon developed, however, to show that some familiar numbers are transcendental. For example, e = 2.718… (the basis of the natural logarithm) was proved to be transcendental in 1873; π = 3.141… (the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter) was proved to be transcendental in 1882, and the list continues to grow. The easiest ways to exhibit transcendental numbers is by studying transcendental functions—like the cosine and sine functions familiar from trigonometry and the exponential function. Leibniz introduced the word transcendence when he proved that such functions are not algebraic functions, and his proof made use of the fact that they are solutions to equations—differential equations, not polynomial equations.

There is a notion of algebraic differential equations that expands the class of numbers that admit finite descriptions far beyond the class of solutions of polynomial equations. Connected to this is a vast framework of conjectures predicated on the expectation that transcendental numbers have a structure and are not simply characterized negatively by their failure to be algebraic. One of the most sophisticated conjectures in transcendence theory belongs to Grothendieck’s theory of motives, to which we return in the next chapter. There is practically no evidence for this conjecture and not the slightest hope that it will be resolved in the next few centuries, but my sense is that everyone working in the field would like it to be true.

In the meantime, Cantor’s theory of orders of infinity had shown that practically all numbers are transcendental. Cantor had introduced the notion of the cardinality, or size, of an infinite set. His methods show that the sets of positive integers, of even integers, of all integers, and of rational numbers all have the same cardinality: they are all countable, or denumerable. The set of real numbers, on the other hand, is not denumerable; it is a much bigger set. Cantor established this by what we can call a trick. A countably infinite set is a set whose members can be listed in numerical order: the first one, the second one, and so on (forever …). Cantor reasoned by contradiction: assuming the real numbers could be so enumerated, he exhibited a member that was not on the list.

Just about every popular book about mathematics explains Cantor’s diagonalization trick,1 so I’ll omit the details. The upshot is that Cantor’s methods show easily that the set of algebraic numbers is countable, which implies that the transcendental numbers are uncountable. You can remove all the algebraic numbers from the number line and hardly notice the difference. But Cantor’s ideas are much more disturbing. The transcendental numbers relevant to Grothendieck’s conjectures are all related to algebraic differential equations and are, likewise, examples of what Maxim Kontsevich and Don Zagier call period numbers.2 These are called periods for the same reason a number like

is called a period—in other words, for a historic reason, the mention of which would add nothing to the present discussion. The period numbers are in turn examples of what Alan Turing, in his paper on machine computation,3 called computable numbers. The latter are the numbers that can be calculated to any degree of accuracy desired by the class of theoretical calculating devices Turing called “universal computing machines” and we call Turing machines.

Turing created the theoretical foundations of computer programming in his landmark paper in the process of defining his computable numbers. In so doing, he also proved that his class of computable numbers is a countable set. This is because you need a computer program in order to compute a computable number, but a computer program is of finite length, so you can enumerate all the computer programs by listing them in a kind of modified alphabetical order. Cantor’s trick then shows that the set of all real numbers is much bigger.

In fact, no matter how we choose to describe numbers, the set of descriptions will be countable. (By a description I mean something more or less informal, like the parenthetical descriptions I provided earlier for e and π. For example, Gregory Chaitin described a number he calls Ω that is designed not to be computable, but since he writes down a description, it can be given its place in modified alphabetical order.) This means that we simply have no way of talking about practically all numbers—not individually, in any case.4

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

P. A.: I was hoping you would say that transcendental numbers answer transcendent questions, because I have a few of those.

N. T.: Well, Vladimir Voevodsky gave a public lecture in which he said that “first-order arithmetic is totally a creation of human minds, there is absolutely no reason for transcendental forces to … ensure its consistency by transcendental means.”5 Since he, and not Frenkel, is performing in the next chapter, I would rather say that the indescribable numbers are the answers to the questions that can’t be asked. But one has to be careful about what one means by that.6 I was careful not to describe the indescribable numbers, though I was in no danger of describing them by accident.

P. A.: I was thinking of Levinas’s “idea of infinity” … but also about the transcendent experience of simultaneously being a character in a play, following the rules set down by the author, and a performer endowed with human volition. Everyone who performs on stage is constantly tempted “to wonder at unlawful things … to practice more than heavenly power permits,” or at least to practice more than what’s written on the page. And we need to yield to that temptation. Otherwise we’re just meat puppets.

N. T.: Doesn’t that very rational account of the experience contradict your definition of transcendent as “whatever escapes rational analysis of any kind?”

P. A.: What I just said doesn’t count as a rational account of the experience any more than calling a number indescribable counts as a description.

N. T.: In his lecture, Voevodsky admitted the possibility of transcendental knowledge of natural things. But he didn’t give any details, so if that’s the sort of thing you have in mind, I’m afraid we’ll have to work it out on our own.

P. A.: Let’s finish with numbers, then. On the one hand, you explain how a description can specify a number; on the other hand, you talk about numbers that can’t be described at all. But how do you know two descriptions can’t specify the same number?

N. T.: You don’t. Any number has multiple descriptions, infinitely many descriptions. For example, “the positive number whose square equals 2” and “the diagonal of the square of length 1” are two ways to describe  . And the word the in “the square of length 1” is infinitely ambiguous. Moreover, if you just start writing down descriptions at random, you’re likely to find yourself describing things that are not numbers. This bottle, for instance, promises un bouquet puissant empreint d’épices de framboises et de notes grillées, which is an example of a description of something that is not a number in any obvious way and that I don’t claim to understand.

. And the word the in “the square of length 1” is infinitely ambiguous. Moreover, if you just start writing down descriptions at random, you’re likely to find yourself describing things that are not numbers. This bottle, for instance, promises un bouquet puissant empreint d’épices de framboises et de notes grillées, which is an example of a description of something that is not a number in any obvious way and that I don’t claim to understand.

P. A.: Tasting wine is a perfect example of a transcendent experience, impossible to capture in words. Whoever wrote that description shouldn’t have bothered. And you number theorists should reserve the word transcendental for the numbers that are answers to questions that can’t be asked.

N. T.: I would take it up with the relevant authorities, but they’re all long dead. Besides, even understanding algebraic numbers in their natural habitat, which is the continuum, requires setting aside time for repeated acts of transcendence. For Hermann Weyl, “The continuum appears as something which is infinitely in the making inside,” a “medium of free becoming.”7

P. A.: Free becoming is a lovely description of the performing artist’s state of being.

N. T.: You do have a gift for paradox. You’ll have to tell me more about your transcendent experiences. As far as indescribable numbers are concerned, the only way to talk about one is to create one, for example, by writing down an infinite string of digits. But to be sure that we’re creating one of these indescribable numbers, we must commit ourselves to writing down the digits in a completely pointless manner, what L.E.J. Brouwer called free choice sequences, for all eternity.

P. A.: We could take turns …

N. T.: At best, we would have just created one of unimaginably infinitely many numbers. And even then there’s no guarantee, unless we have prepared a table of computable numbers in advance, which would fill infinitely many shelves, that we’re not accidentally writing the digits of a computable transcendental number like  .

.

P. A.: I can see how that would get tiresome fairly quickly.

N. T.: And if we ever decided to quit, all we would have done is write a long formula for a probably boring rational number. So we may as well not get started. Anyway, I have a more transcendent idea. Let me switch off the lights again.