2

DR. WESTON PRICE AND HIS STUDIES OF TRADITIONAL SOCIETIES

The name Weston Price has become more familiar in recent years, but is still not widely known. This is ironic in a world that is now—more than ever before—so much in need of the wisdom and knowledge he discovered before his death in 1948. It is heartening that Nutritional and Physical Degeneration, the text of his most important work, is widely available in bookstores and online.

Controversy surrounded the book when it was first published in 1939. Dr. Price was a dentist, and many in his profession viewed his work as profound and significant. So too did many anthropologists; for years, the book was required reading for Dr. Ernst Hooton’s anthropology classes at Harvard University. But the majority of professionals ignored it, and some attacked it. Among the public, there was some enthusiastic acceptance, but the book is long and not an easy read. Not written with an eye to the public, it never became widely read. Nevertheless, it remains a classic. Let’s take a closer look at Dr. Price’s seminal work now.

DR. PRICE’S UNIQUE FINDINGS

Weston Price was born in Ontario in 1870 and raised on a farm. After receiving a degree in dentistry in 1893 and moving to the United States, he began practicing his profession and performing research. His many published articles brought him recognition, and his textbooks on the dangerous effects of root canals became world renowned (if little heeded).

During his years in dental practice, in the children of some of his patients, Dr. Price began noticing problems that the parents hadn’t experienced. In addition to exhibiting more decay, the teeth of many children didn’t fit properly into the dental arch and were, as a result, crowded and crooked. Price suspected that nutritional deficiencies were responsible for this. He also noticed that the condition of the teeth reflected the child’s overall health, which further confirmed his suspicion. Anthropologists had long observed and written about the excellent teeth found in people of primitive cultures. While others in his profession continued looking for external causative factors in dental decay, Price decided to turn his attention to primitive people, and searched for a nutritional factor that might be protecting them from similar dental degradation.

His discoveries may genuinely surprise you. He found entire cultures that had no tooth decay. Nor did he find anyone with misshapen dental arches or crowded teeth. He interviewed an American medical doctor living among Eskimos and northern Indians who reported that in thirty-five years of observation, he had never seen a single case of cancer among the natives who subsisted on their traditional foods. When natives eating white man’s foods developed tuberculosis, this doctor eventually took to sending them back to their villages where they resumed their native diet. Typically, they recovered. In every culture where the people were immune to dental and degenerative disease, biochemical analysis showed the diet to be rich in nutrients that were poorly supplied in modern diets.

Throughout the world in the 1930s, groups in the early stages of modernization were using foods imported from Western countries—sugar, white flour, canned foods, and condensed milk. Price visited and studied cultures where people following traditional ways and diets lived near kinsmen who were eating these foods of modern civilization.

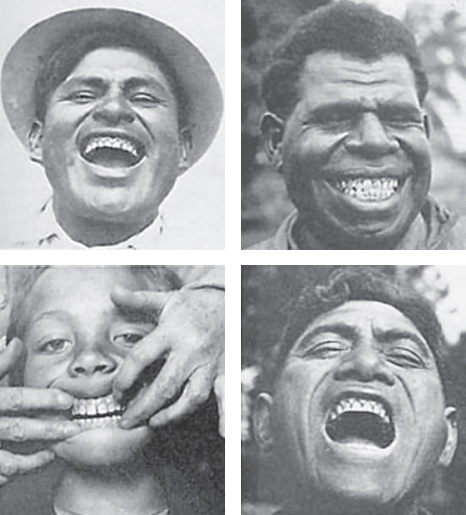

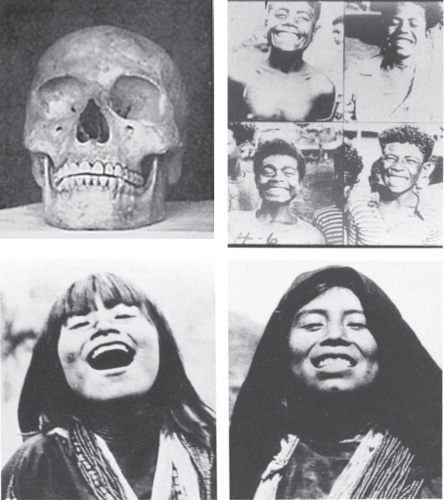

Figure 1.1. These photographs, typical of those taken throughout the world by Dr. Weston Price, are of native people living on traditional foods. Uniformly broad dental arches were found—with all thirty-two teeth present, little or no decay, and no crowding of teeth. (The photographs in this chapter were taken by Weston Price in the 1930s; most appear in his book Nutrition and Physical Degeneration. These prints were made by Marcus Halevi and appear here courtesy of the Price-Pottenger Nutrition Foundation.)

Upper left: Peruvian coastal fisherman

Upper right: Great Barrier Reef (Torres Strait) fisherman

Lower left: Swiss girl (Loetschental Valley)

Lower right: New Zealand Maori fisherman

His travels took him to the corners of the earth. He and his wife, Florence Price, R.N., lived with the Swiss in high alpine valleys; Gaels on islands of the Outer Hebrides; Eskimos in Alaska; Indians in the far northern, western, and central parts of Canada, and in the western United States and Florida; Melanesians and Polynesians in the southern Pacific; Africans in eastern and central Africa; Aborigines in Australia; Malay tribes on islands north of Australia; Maori in New Zealand; and descendants of ancient civilizations in Peru.

Skeletal remains of ancient people were studied by Price wherever they were available. He also studied dental health, keeping detailed records that included thousands of photographs. He analyzed native and modern foods for their calorie, mineral, and vitamin content, and he made extensive studies of the effects of different foods on the chemistry of saliva and its relation to dental decay. Scores of his articles were published, including a series in the Journal of the American Dental Association. He examined the general health of his subjects, and whenever possible, he interviewed medical personnel caring for the people he studied.

Dr. Price’s observations were not limited to health and diet, for he sought to understand the nature and character of these thousands of people he encountered. He came to know many of them well, and his insights reveal the strength of character of many of them, a trait he found typical in native cultures. This chapter chronologically tours Weston Price’s search for health among indigenous cultures all over the world.

EUROPE (1931)

The Swiss of the Loetschental Valley

The Loetschental Valley, nearly a mile above sea level in an isolated part of the Swiss Alps, had been for more than a dozen centuries the home of some two thousand people when the Prices first visited in 1931. The people lived in a series of small villages along a river that wound its way along the valley floor. The completion of an eleven-mile tunnel shortly before the Prices’ visit had made the valley easily accessible for the first time.

The people lived as their forebears had. Wooden buildings, some centuries old, dotted the landscape, with mottoes expressive of spiritual values artistically carved in the timbers. Snowcapped mountains nearly enclosed the valley, making it relatively easy to defend. Though many attempts had been made, the people had never been conquered.

There was no physician, dentist, policeman, or jail. Sheep provided wool for homespun clothes, and the valley produced nearly everything needed for food.

Their crops, many of them on steep hillsides rising from the river, produced winter’s hay for the cattle, and rye for the people. Most households kept goats and cows; the animals grazed in the summer on glacial slopes. Cheese and butter were made from fresh summer milk for use all year, and garden greens were grown in summer. Whole rye bread, made in large stone community baking ovens, was a staple all year, as was milk. Most families ate meat once a week, usually on Sunday when an animal was slaughtered. Bones and scraps were used to make soups that were eaten during the week.

Price examined the teeth of all the children in the valley between the ages of seven and sixteen. Those still eating the primitive diet were nearly free of cavities. On the average, one tooth showing evidence of decay was found for every three children seen.

Many young people examined had experienced a period of rampant tooth decay that suddenly ceased, often having first lost teeth. All the individuals who exhibited evidence of tooth decay had left the valley prior to this period and had spent a year or two in some city. Most had never had a decayed tooth before or since.

Tuberculosis at this time took more lives in Switzerland than any other disease. Yet Swiss government officials reported that a recent inspection of the valley hadn’t revealed a single case of it. Astonishingly, a thorough study of records of death certificates demonstrated clearly that no deaths had occurred from tuberculosis in the history of the valley. This is evidence of profound natural forces at work.

Upon returning to America, Price had samples of the dairy products from this valley sent to him twice a month throughout the year. A pioneer in developing methods for measuring fat-soluble vitamins in foods in the early 1920s, he had written extensively on the subject and was a recognized authority on it. His analyses found these dairy-product samples higher in minerals and vitamins—particularly the fat-soluble D complex vitamins—than samples of commercial dairy products from the rest of Europe and North America.

The vitamin D complex helps regulate the utilization of calcium and other minerals. Price believed that the D complex and another unidentified nutrient he called “activator X” played crucial roles in the excellent general health, immunity to dental disease, and splendid physical development of the people of the Loetschental Valley. The quality of their food was apparently responsible for the presence of rich amounts of these nutrients.

The Swiss people Price studied recognized the crucial importance of their food. The clergymen told how they thanked God for the life-giving qualities of butter and cheese made in June when the cows ate grass near the snow line; their worship included lighting a wick in a bowl of the first butter made after the cows reached this summer pasturage. Price’s analyses showed butter made then was highest in fat-soluble vitamins and minerals.

This late spring butter obviously had a special place in the culture; it was, in a sense, considered a sacred food. Weston Price tested more than ten thousand samples of butter and cheese over the course of many years. Consistently he found the content of fat-soluble vitamins was highest during the months when grass grew most rapidly. For much of North America, there are two such periods, one in late spring and the other in late summer. In more northern areas, the two periods occur more closely together than in southern areas, around midsummer. But for every area, Price’s graph of the fat-soluble vitamin content of the dairy products of the area (plotted against the time of year) echoed a graph of that area’s rate of plant growth (plotted against the time of year). I believe it is no coincidence that this butter contained the same fat-soluble nutrients, from an animal source, that were found in other sacred foods in other traditional and native hunter-gatherer cultures.

Statistics for mortality from heart disease and pneumonia for all districts in the United States and Canada were then plotted. Price found the rise and fall in mortality from these two diseases followed regular yearly cycles in each section of the country. These cycles were exactly opposite the curve for the vitamin content of the dairy products and the curve for the rate of plant growth for that section of the country. In more northern districts, where the twin peaks of the vitamin curve (and also the twin peaks of the plant-growth curve) tended to blend together into one midsummer peak, mortality rates tended to bottom in midsummer. In more southern districts, where distinct peaks occurred (one for late spring and one for late summer) in both vitamin and plant-growth curves, there were two low points on the mortality curve—one in late spring and one in late summer.

Price analyzed the incidence of children’s diseases in Ontario, including chicken pox, measles, nephritis, and scarlet fever. For each disease, a graph of the number of cases was opposite the graph of vitamin levels in the dairy products of Ontario (both graphs were plotted against the time of year).

This is evidence of a direct relation between the quality of foods and the incidence of illness and death. All life depends upon the sun. Is it strange that the green life springing from the sun’s rays, the fresh greens making higher life-forms possible, should prove so vital?

Spiritual values dominated life in this Swiss valley at this moment in time. Part of the national holiday celebration each August was a song expressing the feeling of “one for all and all for one.” Price wrote: “One wonders if there is not something in the life-giving vitamins and minerals of the food that builds not only great physical structures within which their souls reside, but builds minds and hearts capable of a higher type of manhood in which the material values of life are made secondary to individual character.”

He found other evidence of this throughout the world.

Health conditions in the Loetschental Valley were in stark contrast with those in the lower valleys and plains country in Switzerland—modernized areas where rampant dental decay, misshapen dental arches with crowding of the teeth, and a high incidence of tuberculosis and other chronic health problems were the norm. The people of the valley were clearly protected by the quality of their native foods.

Although few of the other traditional groups Price studied consumed dairy products (those who did were certain African tribes, including the Masai), raw, whole milk (both fresh and cultured), cheese, and butter were used in large amounts by the people of the Loetschental Valley. This milk, from healthy, well-exercised animals, was unpasteurized and unhomogenized. Such foods may play a major role in a health-building diet for people genetically able to utilize them well. For the people of the Loetschental, their milk products provided fat-soluble nutrients and minerals essential to maintaining optimal health.

Gaels on the Islands of the Outer Hebrides

The Isle of Lewis and the Isle of Harris, visited by Price after leaving Switzerland, are the chief of these islands off the northwest coast of Scotland. When Price and his wife visited them, they were isolated, and inaccessible much of the year because of constant rough seas. Most islanders lived traditionally, working at fishing, sheep-raising, and farming.

Fish was abundant, and many men went to sea daily. Cod, lobster, crab, oysters, and clams were readily available. Oat grain was the only cereal that grew well and was a staple. The islands were covered with peat, providing poor farmland and pasturage, and consequently people rarely kept dairy animals. Milk was practically unknown; so too were fruits.

Modern foods—white bread, jam, marmalade, canned vegetables, vegetable oil, sugar, syrup, chocolate, and coffee—were available for purchase in shipping ports. Together with some fish, these foods formed the diet of many people in the port towns. Their health was in stark contrast with that of the rest of the population. Children living on seafood, oats, and in summer, vegetables in primitive areas showed less than one tooth out of 100 with any decay. Tuberculosis, cancer, arthritis, and other degenerative diseases were unknown to them.

Children eating modern foods in the several shipping ports, on the other hand, showed an average incidence of 16.3 to more than 50 decayed teeth per 100 examined; even three-year-olds had decay. Tuberculosis was a great problem—some populations had been decimated by it. Wherever Price investigated, afflicted individuals had been eating modern foods. The authorities blamed tuberculosis on the fireplace smoke in the thatched-roof houses that for centuries had been the people’s homes. Yet, former generations had been free of tuberculosis. Only the diet had changed.

Whole grains—rye in the Loetschental, oats in the Outer Hebrides—formed major parts of these traditional European diets. Grains were also important to the few African tribes Price studied. Everywhere else, fish, animals, and vegetables formed the bulk of traditional diets, and grains played little or no role.

Seafood was the other staple in the Outer Hebrides. Fish organs (especially the liver), fish eggs, the head, and the bones were all consumed. A dish considered especially important for children was made from the head and liver of codfish. Since there were no dairy foods, bones used in soups were important because of the calcium and other minerals they contained.

Fish, especially the liver, is a rich source of the vitamin D complex and other fat-soluble nutrients that were supplied primarily by butter, cheese, and milk in the Loetschental Valley. In every culture that Price found free of dental and degenerative disease, a rich source of these fat-soluble nutrients formed a substantial part of the diet—and it is precisely these nutrients that are strikingly deficient in the diet of most modern people.

NORTH AMERICA (1933)

Eskimos of Alaska and Northern Canada

A simple yet stirring story of primitive Eskimos tells of a time when food ran short during the long winter night north of the Arctic Circle, when for months there is no daylight. An Eskimo man takes to stormy seas in a kayak to hunt seal with a harpoon. In darkness, bitter cold, high winds, and rough seas, he searches the dark waters for food. A wave crashing over a kayak can snap even a strong man’s back; as breakers approach, the kayaker rolls the vessel, submerging himself. The tight fit of sealskins between the upper edge of the kayak and his waist keeps water from entering. When the white water passes, he flips upright and continues the hunt, finally killing a seal and returning home with food for his family.

As impressive as Weston Price found the physical strength of primitive Eskimos in Alaska and northern Canada, even more impressive was their character—their courage, honesty, and openness, dedication to family and community, and ability to survive and thrive in the harsh northern environment. In village after village, among Eskimos living entirely on the native diet, Price found virtually no decayed teeth and no evidence of chronic disease. Among those partially subsisting on refined foods, decay and disease increased in direct proportion to the amount of refined food eaten.

The plight of the natives’ modernized brethren was bleak. With no medical help to alleviate their suffering in the years immediately following the introduction of refined foods, many had been driven by the pain and misery of progressive tooth decay to take their own lives. In many small native settlements where the white man’s food was available, some, however, refused it, subsisting entirely on the primitive diet. No evidence of decay or signs of chronic disease were found in them. Their fellow villagers, living the same life except for the fact that they consumed refined foods, had extensive decay, and some had tuberculosis. Among those who had eaten modern foods for several years, some also had arthritis.

In children born of parents who consumed refined foods, the majority had crowding and malocclusion of teeth because the dental arches were too narrow to accommodate the teeth properly. Several of Price’s photographs contained in this chapter illustrate such changes. In contrast is the breadth of the dental arches and the perfect fit of the teeth shown in figures 1.1, 1.2, and 1.5; these Eskimos and other primitives exhibit nature’s normal dental development, found wherever people subsisted entirely on native traditional foods.

This hereditary pattern, normally passed on from generation to generation in accordance with nature’s laws, had been disrupted by the introduction of refined foods. Problems seen in the children of Price’s patients in the United States were, for the first time, appearing in primitive cultures. “Intercepted heredity” was the term Price used for this: the hereditary pattern of perfect dental form, seen clearly in thousands of his photographs, had been intercepted by poor nutrition.

Observation reveals that most people today have crowded teeth; a small minority has the broad dental arches and perfectly fitting teeth that are normal in primitive cultures. And while most people today have the four wisdom teeth (the third molars) removed because of crowding, traditional people nearly always had room for all thirty-two teeth.

Traditional wisdom enabled successive generations to reproduce nature’s perfect pattern. This wisdom in every culture prescribed specific kinds and quantities of foods known to ensure fertility, the birth of healthy babies, and the optimal development of growing children.

In terms of food consumed by the Eskimo cultures that Price visited, the diet, mostly fish and wild animals, was rich in animal fats. Salmon was important. Most primitive Eskimos had homes near deep water, making salmon relatively accessible from the sea. Much of it was dried and then smoked for winter use. When eaten, the fish was dipped in seal oil, rich in vitamin A and also used to preserve sorrel grass and flower blossoms.

Salmon eggs were dried raw and used in quantity; they constituted a source of great nutrition for small children after weaning. Rich in iodine, they were used by women of childbearing age to ensure fertility. The milt of male salmon were eaten by men for the same purpose; this too was eaten raw. Other foods in the Eskimo diet included caribou, especially the organs; kelp, gathered in season and stored for winter; the organs of large sea mammals; and certain layers of the skin of one whale species (analysis showed this was very high in vitamin C). Wild plants and berries were gathered in the summer and stored.

Indians of North America

Great areas of northern British Columbia and the Yukon Territory were still inhabited by Indians in the 1930s when Price visited these places. He went also to reservations in Canada, where Indians lived under more modernized conditions, consuming modern foods, and to Florida to study present-day Seminoles and the remains of pre-Columbian Indians.

Indians living in the Rocky Mountain range in the far north of Canada were unable to obtain any seafood, not even migrating salmon. Winter temperatures of seventy degrees below zero precluded the possibility of growing cereal grains or fruits or of keeping dairy animals. The diet of these Indians was thus almost entirely limited to wild animals.

One old Indian was asked through an interpreter why Indians did not get scurvy. He replied that scurvy was a white man’s disease. Although it was not outside the realm of possibility that an Indian might contract scurvy, the Indians knew how to prevent it and white men did not. When asked why he did not tell white men how to prevent it, he replied that white men knew too much to ask the Indians anything. When asked how it could be prevented, the Indian replied that he must go to his chief for permission to divulge the secret. Upon returning—with permission—he explained that when an Indian kills a moose, he opens it up and finds a small ball in the fat above each kidney. He cuts these balls—the adrenal glands—into pieces that are immediately eaten, one by each person in the family.

We now know that the adrenal glands are among the richest sources of vitamin C in all animal or plant tissues. Cooking destroys vitamin C. The Indians’ empirical knowledge and use of different organs and tissues of animals has certainly been verified by modern methods of analysis. Their wisdom preceded the discovery of vitamin C by thousands of years.

Such wisdom is again demonstrated in a story of a white man running out of supplies while crossing a high plateau in the far north country just before the fall freeze-up. A doctor of engineering and science, he was forced to march out of the wilderness when his prospecting plans went awry. While crossing the plateau, he went almost blind with a violent pain in his eyes that persisted for days. He nearly ran into a grizzly one day; an old Indian tracking the bear recognized the white man’s plight.

The Indian led him to a nearby stream, and with a trap of stones, caught some trout. Throwing the fish on the bank, he told the prospector to eat the flesh of the head and the tissues behind the eyes. In a few hours the man’s pain was largely gone. In a day his sight was returning, and in two, it was close to normal. He had been suffering from xerophthalmia, due to vitamin A deficiency.

The fatty tissue around the eyes is one of the richest sources of vitamin A in any animal’s body.

For nine months of the year, the nutrition of these northern Indians was mostly wild game, chiefly moose and caribou. Emphasis was placed on eating organs, including the wall of parts of the digestive tract, which are rich in vitamin D. Some meat and organs were eaten raw; much muscle meat was fed to dogs. Bone marrow was consumed, especially by children. Plants were consumed in summer, and some bark and buds of trees in winter.

The thyroid glands of the male moose, greatly enlarged during the fall mating season, were eaten liberally by men and women in moose country near the Arctic Circle. The Indians said this caused a large percentage of children to be born in June, the best time to bring infants into the harsh northern environment. A known, direct relationship exists between thyroid gland activity and fertility.

The teeth of several primitive groups that Price examined showed no indication of decay. In these and other groups, a total of eighty-seven Indians living on the native diet were examined; only four teeth ever affected by decay were found. As well, there were almost no irregular teeth and no impacted third molars found. Inquiries were made about tuberculosis and arthritis; not a single case was seen or heard of among isolated groups.

However, many crippling cases of rheumatoid arthritis were seen at the point of contact with refined foods, and tuberculosis was taking a severe toll. Tooth decay was rampant, and crooked teeth with deformed dental arches were typical.

Josef Romig, a surgeon known then as the most beloved man in Alaska, was interviewed by Price at the government hospital in 1933. Dr. Romig had served primitive and modernized Eskimos and Indians for thirty-six years. He stated that cancer was unknown among truly primitive natives. He had never seen a case, though when the Eskimos and Indians began eating refined foods, it frequently occurred. Other acute medical problems requiring surgery, common among modernized Eskimos and Indians, were similarly rare among primitives.

Such experiences led Romig to begin sending modernized natives afflicted with tuberculosis back, when possible, to native conditions and a native diet. Though the disease was generally progressive and eventually fatal when patients remained on refined foods, he found that a great majority of them recovered when they reverted to a traditional diet.

During those years, a physician in Los Angeles with a keen interest in nutrition was using a strikingly similar diet in treating patients with tuberculosis and other chronic diseases. This physician, Francis M. Pottenger, Jr., would soon conduct and publish studies validating the use of a diet rich in high-quality animal-sourced foods, especially raw and lightly cooked organs. (Pottenger’s investigations into the effects of cooking upon foods and his discoveries about the role of animal foods in healing chronic diseases will be presented in chapter 5.)

Price also interviewed the physician directing the hospital on Canada’s largest Indian reservation in Brantford, Ontario. The doctor explained that during his twenty-eight years there, the services that the hospital offered had changed completely. He had had contact with three generations of Indian mothers. The grandmothers of the current generation had given birth without difficulty in wilderness homes, but current mothers often were in labor for days, and surgical interference was frequently necessary. As a result, the main function of the hospital had changed to address problems related to problems associated with maternity. All reservation Indians ate refined foods.

Seminole Indians in Florida were studied and comparisons were made with skeletal material from pre-Columbian Indians in museums. Some Seminoles still lived in relative isolation in the Everglades and in cypress swamps; others lived near communities consuming modern foods along the Tamiami Trail and near Miami.

Several hundred pre-Columbian skulls from burial mounds in southern Florida were examined; not one decayed tooth or a single dental-arch deformity resulting in crowded or crooked teeth was found. A comparison of the skulls’ thickness with that of recent skulls showed the older skulls were much thicker, providing further evidence of superior physical development in the native culture. Pre-Columbian skeletons showed no evidence of arthritic joint involvement; many Indians eating modern foods had bony deformities derived from rheumatoid arthritis, along with tooth decay.

The original inhabitants of North America had great wisdom about utilizing foods native to the land. Most Indian cultures ate quantities of superior quality animals and seafood to maintain resistance to disease, great physical strength, and normal reproduction. As with the Eskimos, this often was accomplished on diets of mostly fish and wild animals, supplemented by plant foods.

Native Americans and other native cultures throughout the world had detailed information about using specific parts of animals and the unique importance of each part. Many sources also indicate a vast knowledge of the medicinal uses of herbs. The development of these cultures was not simply a matter of people randomly eating whatever was available. Rather, cultures passed on the accumulated wisdom of the group to the next generation. This wisdom was concerned with laws of nature that, when ignored, lead to sickness, death, and the degradation of succeeding generations.

We know not from where this wisdom came. We only know that it has disappeared from the consciousness of the vast majority of people alive today.

Western culture has mobilized the intelligence and resources to send men to the moon, make color televisions, and plumb the atom’s depths. Yet, modern people have failed to recognize that the native people who were exterminated knew a great deal about maintaining the biological integrity of the human species. As millions of people continue down a path of disease and suffering, modern medicine obstinately refuses to recognize that the fundamental cause lies in the way most people eat. And the way a person eats is merely a reflection of the way he or she thinks and lives.

THE TROPICS

Melanesia, Polynesia, and Hawaii (1934)

The tropics were of interest to Price because he sought universal factors affecting people everywhere, regardless of climate, race, or environment. Melanesians (on New Caledonia and the Fiji Islands) and Polynesians (on the Hawaiian, Cook, Tongan, and Marquesas Islands, and the Tuamout group, including Tahiti) were visited. Arrangements had been made through government officials, leading everywhere to a cordial reception.

Detailed records on physical development, the condition of every tooth, the shape of the dental arches and face, and kinds of foods eaten were kept for each individual. Special or unusual physical characteristics were photographed. More isolated members of each tribe were compared with those living in the vicinity of the port or landing place of the island.

Government reports revealed exactly what was imported. Nearly always, 90 percent of the total value of imported goods consisted of white flour and sugar. This was true everywhere Price traveled.

The magnificence of the islanders of the South Seas—as reported by early European explorers—is legend. They were a strong, beautiful, and kindly people. The islands had been densely populated. But by the time Price arrived, these populations had been decimated—mostly by tuberculosis, but also by smallpox and measles.

He paints a distressing picture of the majority of the people remaining. Most used little of the seafood staples of their ancestral diets, and in addition to some vegetables and fruits, they ate foods made with white flour and sugar. Decay was found in more than one-third of the teeth examined. Many individuals suffered from tuberculosis, and dental-arch deformities were common in the youth.

Relatively isolated groups were found, though on many islands there were few such groups. The native diet was mostly shellfish and fish, eaten together with land plants, fruits, and sea vegetables, all selected according to a definite program. Much shellfish was eaten, often raw, as were many small fish. Underground ovens of hot stones were used for cooking. Taro root was dried and powdered, then mixed with water and fermented. The incidence of decay was about one tooth in every two hundred examined, and dental arches were uniformly broad, with no crowding of teeth.

Viti Levu, one of the Fiji Islands, is one of the larger islands in the Pacific. Price hoped to find natives in the interior living far enough from the sea to be dependent entirely on land foods. He could not. Everywhere in the interior, piles of seashells were found.

Food from the sea had always been considered essential, his guide told him. Even when at war with coastal tribes, arrangements existed whereby interior tribes sent special plant foods by courier to coastal tribes in exchange for seafood. The couriers were never harmed. Land animals, including pigs, an excellent source of vitamin D, and freshwater fish, supplemented what seafood inland tribes could get. No places were found where seafood was not eaten.

The same physical changes seen in natives eating modern foods in Switzerland, the Outer Hebrides, Alaska, northern Canada, and Florida were seen in the islanders of the South Seas who had abandoned traditional native diets. Similarly, tuberculosis and arthritis had become prevalent.

The isolated groups immune to these problems were largely eating animal-sourced diets, which provided large supplies of fat-soluble vitamins and other nutrients. The source in the South Seas was seafood.

Groups maintaining immunity to dental and chronic disease on diets consisting entirely of vegetable matter had been especially sought by Price but none were found. As his studies progressed, it emerged ever more clearly that healthy, free-ranging animal life of the land and sea provided humans everywhere with essential nutrients apparently unobtainable in adequate quantities from plants.

Many individuals have recovered from diseases on vegetarian diets. Most of these diets have included dairy foods and at least the consumption of occasional fish or poultry in their regimens. When well-balanced, such natural diets are far superior to the diets rich in white flour and sugar that most people consume today. Strictly vegetarian diets that exclude all animal foods (known as vegan diets) often initially result in better health and the alleviation of serious problems.

But the success of vegan diets is usually self-limiting. By avoiding all animal foods and animal fats, nutrients essential for the development of optimal strength, resistance to disease, and reproductive capacity are lacking. Individuals on strictly vegan diets may thrive for several weeks, months, or even years, but in the vast majority of cases, problems—including mental illness—eventually appear.

I recall my first philosophy teacher in naturopathic medical school. Crusty and old-fashioned, the doctor had practiced for many years. Surveying thirty-six rather thin and predominantly vegetarian students on the first day of class, he stated, “Most of you people look like you could use a good steak.” Deciphering reality through the smokescreen of preconceptions is never easy. The idea that all natural foods build good health is a common preconception, but behind it lies reality: even when one eats mostly natural food, precisely which foods are emphasized determines the course of health and disease.

AFRICA (1935)

The magnificence of Africa has been partially captured in several films: vast rolling plains; primordial sunsets; thundering herds of wild animals; lilting, billowy clouds of long-necked snow-white birds; lions ripping and tearing at flesh before charging the camera. The Africa that Price visited was very beautiful but, like the other cultures he studied, its beauty had begun to vanish. But the land proved more permanent and less quickly damaged than the inhabitants, and even today much of its beauty remains.

Last to receive the sometimes dubious benefits of modern civilization, the African continent in 1935 contained scores of tribes living according to native ways. Price’s travels in Africa covered more than six thousand miles. Thirty tribes were studied and more than twenty-five hundred photographs taken. Price’s most indelible impression: the contrast between the rugged resistance of the natives to their harsh environment and the fragility of foreigners.

A racial difference this was not, for when the natives abandoned primitive foods for refined foods, they developed dental decay and became susceptible to infectious processes to which they were previously immune. These included malaria, dysentery, and tick-borne diseases such as sleeping sickness. The immunity experienced when eating native foods extended to chronic disease; an interview with the doctor in charge of a government hospital in Kenya revealed that in his several years of ser-vice among native people eating the native diet, he had seen no cases of appendicitis, gallbladder problems, cystitis, or duodenal ulcer.

In several tribes studied, no evidence of tooth decay was found, nor a single malformed dental arch. Several other tribes had nearly 100 percent immunity to decay, and in thirteen tribes no irregular teeth were found. Where some members had moved to cities and adopted modern foods, however, extensive decay was found. Children born of these individuals often showed narrowed dental arches with crowding of the teeth.

A wide range of diets was encountered, and differences between tribes were seen in physical stature and strength of typical individuals; stronger tribes dominated weaker neighbors. Among tribes studied were the following.

Nilotic Tribes, Including the Masai

Herders of cattle and goats, the people lived on milk, meat, blood from their steers, plants, nuts, and fruits. Blood was whipped in a gourd and the clot cooked. The liquid remaining, especially important in the nutrition of children, pregnant and lactating women, and warriors, was consumed raw.

These cattle people were superbly developed physically, brave, and mentally sharp. Every Nilotic tribe observed dominated its agricultural neighbors. This was not an undesirable trait or a sign of over aggression, for in the harsh African environment, as in all of nature, survival of the strong often was at the expense of the weak. The strength of the cattle people helped ensure their survival.

Protection of their animals from predators called for greater skill and bravery by the Masai than required of other African tribes. One or two men or boys often guarded entire herds with only spears. Price called the skill of Masai in killing a lion with only a spear “one of the most superb of human achievements.” Scenes in films of lions in full charge—absolutely frightening images—give an indication of the courage involved in this practice.

Eighty-eight Masai were examined by Price; all were cavity-free.

The Kikuyu

These neighbors of the Masai were primarily agricultural, eating mostly sweet potatoes, corn, beans, bananas, millet, and insects. Smaller and much less rugged than the Masai, their teeth were quite good, but not up to the standard of cattleherding tribes; 5.5 percent of teeth examined showed cavities. Dental arches were generally well formed.

For six months prior to marriage, young Kikuyu women used a special diet including extra animal-sourced foods; these foods were also emphasized in pregnancy and lactation. Children were spaced at least three years apart and each pregnancy was preceded with special feeding. Such practices were typical of native cultures everywhere.

The Maragou

Strong and well-developed, these people ate quantities of fish, whole grains, sweet potatoes, and other plant foods. One tooth with a cavity was found in the nineteen individuals examined.

The Muhima

These cattle-raising people lived on meat, milk, blood, and wild plant foods. They were tall, strong, and dominant, defending their families and animals with spears. This was one of six tribes Price found that had no tooth decay.

Sudan Tribes, Including the Neurs

These herdsmen supplemented milk, blood, and meat with fish and shellfish from the Nile River. Among the Neurs, women were often more than six feet tall; men more than seven. No cavities were found in any people of this tribe.

They believed the seat of the soul was the liver and considered it their most important food. The growth of a person’s character and body was said to depend upon feeding that soul by eating the livers of animals. In that sense, liver seems to have been considered a sacred food for this culture; a food with both physical and spiritual dimensions not found in other foods.

Other Agricultural People

The chief foods of other agricultural people were corn, beans, millet, sweet potatoes, bananas, and other grains. The people were smaller than herdsmen and tribes consuming large amounts of freshwater fish, and indeed, they had been dominated by such tribes.

Other groups that had a diet made up chiefly of whole grains were examined at ports and missions. The individuals were not eating as their ancestors had. Some kept a few animals and most consumed some milk and fish. Six to eight percent of the teeth of individuals in these groups had cavities.

Wherever natives had used large amounts of refined foods for some time, decay was rampant and tuberculosis prevalent; other chronic diseases appeared eventually. Dental arch abnormalities commonly appeared in the next generation.

Modernized natives were aware of a problem. Native boys at mission schools often asked why they were not as strong as boys growing up without contact with mission or government schools. As in other places that Price had visited, the contrast between traditional and modern natives was stark. These words of a mining prospector, spoken after twenty years among the native people of Uganda, echo the sentiments of many people who observed native cultures: “The heaven of my choice in which to spend all eternity would be to live in Uganda as the natives of Uganda lived before the coming of modern civilization.” Perhaps he romanticized. Yet such reports were not uncommon, nor are they inconsistent with recent reports by contemporary anthropologists studying surviving hunter-gatherer cultures.

Tribes eating grain-based natural food diets had well formed dental arches and resistance to infectious diseases, but their physical development, resistance to dental decay, and strength was inferior to tribes eating more animal foods. The people strongest physically and often 100 percent resistant to dental disease were herdsmen-hunter-fishermen. In towns and ports where some groups ate a combination of refined and primitive foods, problems developed, but not to the extent occurring when native foods were abandoned entirely.

Native people everywhere discovered essentials of life and, following fundamental nutritional laws, lived in harmony with nature. Modern civilization has chosen to ignore these fundamental truths. The sophistication of our technical knowledge has bred an arrogance that precludes an appreciation of the so-called primitives’ superior skill in interpreting cause and effect. The wisdom of native societies in understanding laws of nature and living in harmony with these laws is a treasure humanity must not lose if we ever wish to regain our lost strength and resistance to disease. And yet, each day that treasure slips further and further from our grasp as the few remaining native cultures are encroached upon by the expansion of civilization into their habitats.

Words like “primitives” and “savages” reveal our prejudices. Most writers have emphasized aspects of native cultures that reinforce these images. Representatives of a Western civilization exporting religion and refined food to the rest of the world refused to realize they gave little for what they took and were unable to see that nonwhite people had something to teach them. Immoral actions were accompanied by a lack of common sense; Westerners failed to learn from cultures that, through destructive ignorance and malicious exploitation, were being forever destroyed. The degradation of traditional moral values in modern societies is a matter of concern.

Herein we have concerned ourselves primarily with matters of a physical nature, however, references to the more spiritual and moral qualities of the native people Price met warrant some review. Dr. F. M. Ashley-Montagu, a world-renowned anthropologist and author of various popular and scholarly books, wrote in his article in the June 1940 issue of Scientific Monthly, “The SocioBiology of Man”: “In spite of our advances, we spiritually and as human beings are not the equal of the average Aboriginal or Eskimo—we are very definitely their inferiors. We lisp noble ideals and noble sentiments—the Australians and the Eskimos practice them—they neither write books nor lecture about them.” Decades later, the truth in this statement has become even more apparent.

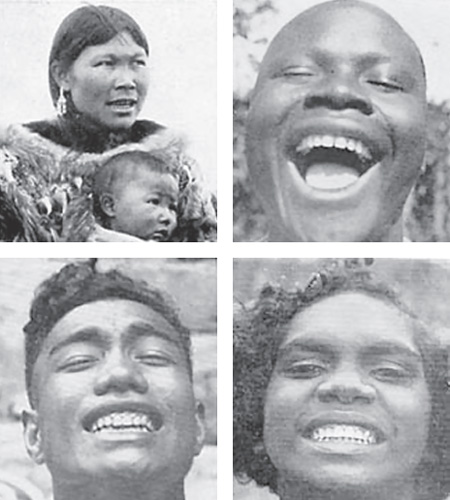

Figure 1.2. Further examples of the remarkable but quite natural physical development resulting wherever people ate according to the traditional wisdom of their culture.

Upper left: Eskimo woman and child

Upper right: African woman

Lower left: Samoan man

Lower right: Aborigine woman

Though currently many would prefer otherwise, nutrition is not a matter of opinion; nor are the ideals of truth, honesty, integrity, loyalty, and service that have been held in common in traditional societies the world over by thousands of generations. The price of modern society’s decision to ignore natural laws governing these fundamental aspects of human life has resulted in the spiritual bankruptcy that threatens Western society today.

AUSTRALIA, THE TORRES STRAIT ISLANDS, AND NEW ZEALAND (1936)

Aborigines of Australia

Price wished to study many different cultures in order to witness as wide a range in their physical conditions as possible. More than one-half of Australia receives less than ten inches of rain per year. Poor soil and subsequent scanty plant and animal life in the interior regions made the physical condition and culture of Aborigines there all the more remarkable.

Their skill in tracking and trapping animals was renowned; they were said to see animals moving over a mile away. Their social organization too was quite remarkable. Aboriginal boys and girls were required to pass through a long and involved series of tests and trials (physical, mental, and moral) to enter adulthood. People knowing them well invariably stated that Aborigines never stole and were completely trustworthy.

They were a spiritual people who believed in an afterlife. The stars to them represented spirits of ancestors. Indeed, spirits of great character made up the constellations, and aboriginal youth learned their names. These were people who had conquered life’s temptations and lived completely in the interest of serving others. Aborigine spirituality was built upon this principle.

In every isolated primitive group, Price saw physical excellence in all individuals. But the majority of Aborigines had been deprived of their homelands, placed on reservations, and enslaved as laborers. The contrast between them and those left alone was more extreme than any place Price had seen. Whites who enslaved Aborigines ate the same refined foods, and their physical degeneration was equally marked.

Aborigines from both interior and coastal districts were studied. Special effort was made to examine children aged ten to sixteen after their permanent teeth had come in. Only then could the developing shape of the adult dental arch and pattern of the adult face be determined, allowing a full assessment of the effects of the individual’s nutrition.

A large number of skulls of Aborigines in museums at Sydney and Canberra were also examined. Aborigines living primitively all had broad, beautifully proportioned faces, with wide and well contoured dental arches. Museum skulls too were uniformly excellent.

Aborigines near the coast were larger than those of inland tribes, and skulls from near the coast were more massive. Coastal people ate quantities of fish, sea cow, a great variety of shellfish, sea plants, land plants, and fruits. Inland food was scarcer; people ate roots, stems, leaves, berries, seeds, large and small animals of every variety (including rodents, insects, beetles, and grubs), various animal life from the rivers, birds, birds’ eggs—nearly everything moving or growing.

All of those examined in primitive groups from both coastal and inland places had excellent bodies, with almost no decay or abnormalities in the shape of the dental arch and face. Apparently this had been the case for thousands of years, for the primitive museum skulls were all perfect.

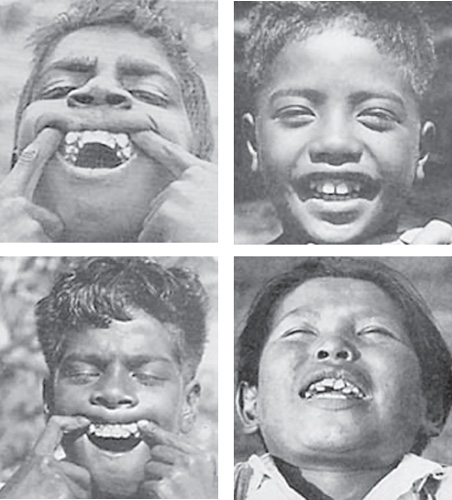

Figure 1.3. Typical changes occurring in the first generation born after the introduction of refined foods shows narrowing of the dental arches with subsequent crowding of teeth. These problems occurred in addition to the agonizing dental decay that both parents and children experienced.

Upper left: Aborigine boy

Upper right: Polynesian boy

Lower left: Torres Strait Islands boy

Lower right: Eskimo boy

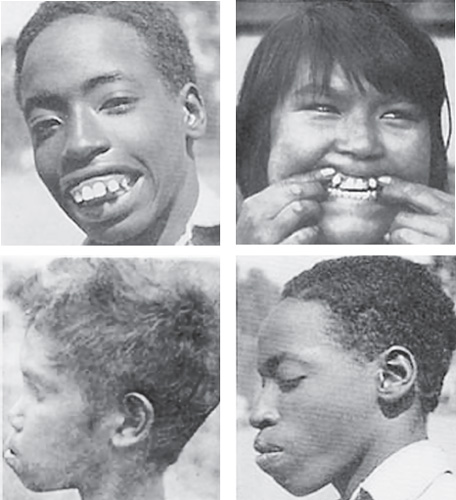

Figure 1.4. Further examples of degenerative changes typically seen in children born of parents eating refined foods.

Upper left: African boy with extreme protrusion of the upper teeth and shortening of the lower jaw.

Upper right: Eskimo girl with crowding of the upper dental arch, which has caused the bicuspids to protrude. This is often seen in cultures eating refined foods. Contrast this with the young people in figures 1.1, 1.2, and 1.5.

Lower left: Aborigine boy. Changes in the shape of the face and dental arch have caused the lower jaw to be thrust forward. Price virtually never saw such changes in people eating native, natural food.

Lower right: African boy with the same thrust of the chin found in a boy on the other side of the world. The cause is the same.

Those forced to eat refined foods showed, in the next generation, the same dental abnormalities present in white people. Tuberculosis and crippling arthritis became common, particularly among those with no access at all to native foods.

The story of the Aborigines is perhaps sadder than that of other native peoples decimated by contact with Western civilization because the Aborigines were so completely exploited. They are a reminder that the white man was not welcome in primitive lands; guns were his introduction and the arbiters ensuring his stay. Perhaps natives in some places welcomed Westerners at first, but had they seen everything that was to come, they almost certainly would have resisted initial contact more strongly.

The processes destroying traditional cultures were so insidious as to be perhaps unrecognizable in early stages. Who was to know that the white man’s food would lead inevitably to sickness and death and that the biological integrity of thousands of generations would be disrupted? When conditions deteriorated, it was in most cases impossible to return to traditional ways.

Some native people exposed to Westernization chose to maintain traditional ways, however, entirely refusing to eat the white man’s food. These people also maintained their strength, health, and integrity. Perhaps they served as models for any of their fellows seeking help.

Torres Strait Islanders

The Torres Strait is the body of water between northernmost Australia and southernmost New Guinea. Many small fertile islands supported populations of several hundred to a few thousand people when Weston Price visited this region. Government stores selling refined foods had in recent years been established on many of these islands. Before a local market economy took hold here, adults had reached maturity eating only native food; very few other factors in the environment had changed.

Surrounding waters were rich with fish and shellfish. Plant foods too were abundant and of such importance that Thursday Island, the location of the administrative center for the islands, was not originally inhabited because the soil was poor. The native diet consisted of a great deal of fish and shellfish of many kinds, tropical plants, seaweed, taro, bananas, papayas, and plums.

Natives living on native foods had practically no cavities. Most had broad, normal dental arches. They were a happy, peaceful, and contented people; there was almost no crime.

Thursday Island was the home of the majority of whites in the Torres Strait; imported foods had been available for several decades. Native people lived mainly on the rest of the islands and acutely resented the intrusion of modern ways, particularly refined foods. Government stores were seen as a danger, and on several occasions the issue had nearly provoked violence. Perhaps the people intuitively saw the threat posed by the “white man’s foods.”

The incidence of dental decay on a given island was directly proportional to how long a store had been present there. Children born after parents began using refined foods often developed abnormal dental arches, as did a large majority of white children on Thursday Island.

The government physician for the Torres Strait islanders stated that in his thirteen years with them, among the native population of four thousand he had never seen cancer. He had operated on several dozen malignancies among the white population of about three hundred. Among natives, any conditions requiring surgery were extremely rare.

The general health and resistance to disease of traditional cultures is demonstrated in interviews with the physicians who spent years with these people. Though Price focused primarily on dental health, his studies showed that a resistant individual developed neither dental disease nor other disease. He noted that people suffering from tuberculosis and rheumatoid arthritis nearly always had extensive dental decay. Physicians interviewed consistently stated that native people living on traditional diets remained nearly or entirely free of all disease. This was observed by early anthropologists, and confirmation has recently come in the form of several research articles, to be discussed later in this book.

New Zealand Maori

The reputation of the Maori among Western anthropologists has, since the first Europeans sailed to New Zealand, been that of the most physically well developed people in the world. An early study of two hundred and fifty Maori skulls revealed only one tooth per two thousand with a cavity, and nearly 100 percent had normally formed dental arches. This was superior to even the Eskimos.

According to Price, Maori have told a man at a telescope exactly when an eclipse of a satellite of Jupiter, supposedly invisible to the naked eye, was about to occur. Paintings in cave dwellings in other parts of the world reveal that some prehistoric people saw stars that we see only with telescopes.

Weston Price traveled eighteen hundred miles through twenty-five districts examining native Maori families and children in native schools that were in various stages of modernization; the cavities rate varied with the degree of change. In more isolated groups, 2 percent of the teeth had been attacked by decay, and in many districts 100 percent of the older generation had broad, normal dental arches. In modernized groups, from 40 to 100 percent of the younger people had abnormalities.

Tribal tradition placed much emphasis on shellfish, especially certain species, as was the case throughout the Pacific. Kelp (seaweed) and fern root were eaten in quantity. The Maori relied primarily upon the sea for nourishment.

SOUTH AMERICA

Ancient and Present-Day Peruvians (1937)

Long before Spaniards pillaged the Mayan and Aztec civilizations of Mexico and South America, cultures flourished in Peru, existing in the high plains country of the Andes Mountains and the arid desert region extending from the Pacific Ocean to the Andes. This desert, forty to one hundred miles in width, runs one thousand inhospitable miles down the length of South America and is marked by vast sand dunes with scarcely a sign of greenery.

Figure 1.5. Archeological evidence studied in several countries—skulls and teeth from ancient cultures—showed in generation after generation that tribal patterns repeated themselves with no significant changes.

Upper left: This ancient Indian skull was among the skeletal remains Price studied in North America, Australia, and Peru. In Peru, he examined 1,276 successive skulls without finding one with the narrowed dental arches of most modern people.

Upper right: Melanesian boys. These four boys lived on four different islands and were not related. Each had nutrition adequate for the development of the physical pattern typical of Melanesian males; thus their similar appearance.

Lower left: Peruvian jungle Indian girl

Lower right: Peruvian jungle Indian woman

But throughout are found complex foundations of fortresses and extended residential areas from past civilizations. Great aqueducts brought water from the mountains, enabling people to grow quantities of corn, beans, squash, and other plants in river bottoms where alluvial soil from the Andes had collected for ages past. These foods, and the seafood consumed, nourished the cultures there.

Mummies of ancient inhabitants have been found in this desert region. Indeed, fifteen million mummies were estimated to be in the burial mounds found along the entire coast. Many articles were buried with these mummies, including jars containing food and items the dead person used in life. Nets and the tackle of fishermen were buried with many. The foundation of these cultures was ultimately the animal and marine life of the Pacific Ocean. Sweeping north from Antarctica, the Humboldt Current carries with it sources of food that support a vast population of fish and shellfish.

Thousands of mummified specimens, well preserved because of the dryness of the climate, existed in Peruvian museums. Skulls of 1,276 ancient people were studied by Price; not one significant deformity of the dental arches was found. Each showed normal broad arches capable of accommodating thirty-two teeth without crowding.

Villages were visited where descendants of one of these ancient cultures lived. Isolated on the north coast of Peru, they were fisherfolk who lived traditional lives and didn’t consume modern food. Their physical development was excellent.

Cultural achievements of these ancient civilizations were considerable. Engineering feats remain unexplained. The great aqueducts of the coastal people, sophisticated and estimated to be capable of delivering sixty million cubic feet of water per day over distances of up to one hundred miles, were cut through boulders without hardened tools or blasting powder. Roads and suspension bridges built by the Incas crossed mountain divides fourteen to sixteen thousand feet above sea level, linking all parts of the empire to Machu Picchu, their mountain fortress. A superb engineering achievement, the walls were built of white granite lifted from quarries in a riverbank two thousand feet below.

The Tauhuanocan culture preceded the Incan and left magnificent monuments. One of the largest single stones ever moved and used in a building is found in one of their temples; it is thought to have been brought more than two hundred miles through mountainous country. Many structures from this culture are found in the Andean Plateau from Bolivia to Ecuador, all characterized by intricately fitted, manysided large stones, some of them twenty feet long. The fit is such that most crevices do not allow for the passage of a knife point.

How were the stones cut and moved, and how were they and the white granite of Machu Picchu raised? No one knows.

The Incan society was a highly organized and perhaps successful socialistic state. Some sources report there was no hunger or crime, and that the ruling Incan carefully practiced laws his people were required to live by.

Foods in the high plateau country of the Incan and Tauhuanocan cultures were less diverse than those found at the coast. Plants and grains were consumed. These included potatoes, corn, several varieties of beans, and quinoa, a seed cereal. Llamas and alpacas were domesticated, and some wild game was available. A colony of guinea pigs was kept by each household for food; we now know they provided a rich source of vitamin D.

When Price visited, dried fish eggs and kelp were regularly obtained through commerce with the coast and were universally available in high-country markets; for centuries this had been so. The Indians said dried fish eggs were necessary to maintain fertility, and kelp was necessary to prevent the “big necks” whites often developed—the enlarged thyroid gland (goiter) that results when the body attempts to compensate for a deficiency of iodine.

Skulls from pre-Columbian burials in the mountains were studied. All were free of dental decay, with broad dental arches and well-developed third molars.

Despite the severe climate of the mountains and the arid conditions of the coast, ancient Peruvians of both areas developed ways of eating and living that led to physical integrity and significant cultural achievements. The accumulated wisdom of their centuries of living in harmony with nature has been largely forgotten. Subsequently, people in these lands have developed diseases and structural, physical problems inherent to the use of refined foods.

Andes Mountain Indians

In high mountain plateaus of southern Peru and Bolivia, many descendants of the ancient Tauhuanocan and Incan cultures still lived according to their ancestors’ methods. Market day was characterized by trade and socializing. On such days, Price had opportunities to examine several groups. Contact was arranged through local authorities.

The most isolated groups showed the lowest incidence of tooth decay and degenerative changes. No decayed teeth were found in one group of twenty-five; each individual had all teeth normal for his or her age.

Strength and endurance were characteristic of the Indians of the Andes Mountains who typically carried loads in excess of two hundred pounds all day long, day after day. In freezing weather they slept with ponchos about their heads; their legs and feet remained bare. Many lived at elevations of twelve thousand feet or more.

While native cultures in Switzerland and Georgian Russia used quantities of dairy products, Andes Indians achieved physical excellence without them, for dairy animals introduced to the Andean climate had never adapted to it. Llamas, wild birds, and guinea pigs were the animal foods consumed by inhabitants here.

Amazon Jungle Indians

The Amazon region of Peru begins in the eastern foothills of the Andes, where fertile soil, warm climate, and abundant rainfall generates fish-filled streams and forests rich with tropical vegetables, fruits, and wild animals. Price met and examined a group of thirty Amazon jungle Indians who lived in this area.

They were a proud, beautiful people with great strength. They exhibited no evidence of dental decay; each individual had perfect dental arches. Another tribe of the same ancestral stock was in contact with a mission and had reduced the use of native foods in favor of refined foods available through the mission. As a result, many members of this tribe had rampant tooth decay, and young children had dental-arch deformities. They were becoming civilized.

Decay and missing teeth were expected. But Weston Price’s monumental study for the first time thoroughly and convincingly linked many other problems to inadequate nutrition. Among these problems were changes in the shape of the dental arches, head, and face; infertility, miscarriage, difficult labor, and birth defects; susceptibility to acute diseases; and prevalence of tuberculosis, arthritis, cancer, and other chronic diseases. Price also wrote of the relationship between inadequate nutrition and criminality and mental deficiency. His discovery of characteristic animal nutrients in the diets of all groups enjoying immunity from these problems further adds to the revolutionary impact of his findings.

CONCLUSIONS OF THE MEDICAL COMMUNITY PERTAINING TO DIET AND DISEASE

In response to controversy about the role of diet in degenerative diseases, a consensus emerged within the medical profession in the second half of the twentieth century that animal fats and foods rich in cholesterol were harmful. There is no truth to this assertion, which has been used to reach numerous faulty conclusions.

Analysis of the deterioration of the modern diet is complex. Beyond the decline in quality, traditional wisdom about the use of different organs and tissues of animals has been forgotten or ignored. Liver, for example, is seldom eaten today. But in all traditional cultures, liver is among the most important of foods.

The displacement of traditional foods by refined foods is the heart of the problem. Attempts to cite the single issue of animal fats and cholesterol as the chief problem and solution are misdirected and sidestep issues central to a reasonable approach to health and disease.

While Price was a pioneer, other scientists have studied traditional cultures and concluded that food is almost certainly responsible for the nearly complete protection that hunter-fisher-gatherers enjoy from dental and chronic disease. Recent publication of this work and research comparing oils and fats in fish and wild game with those in domestic animals will be reviewed shortly, after completing our travels with Weston Price.