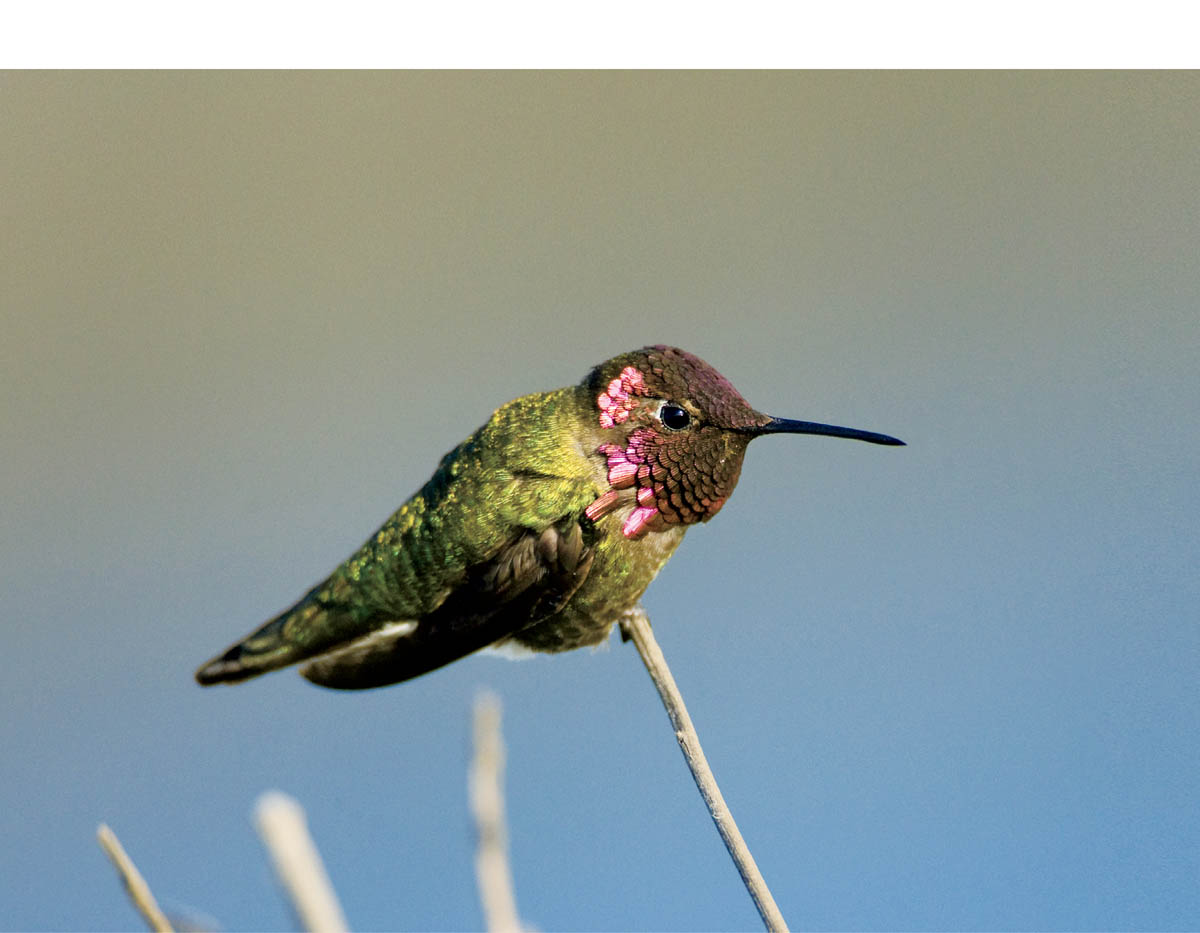

Anna’s Hummingbird male

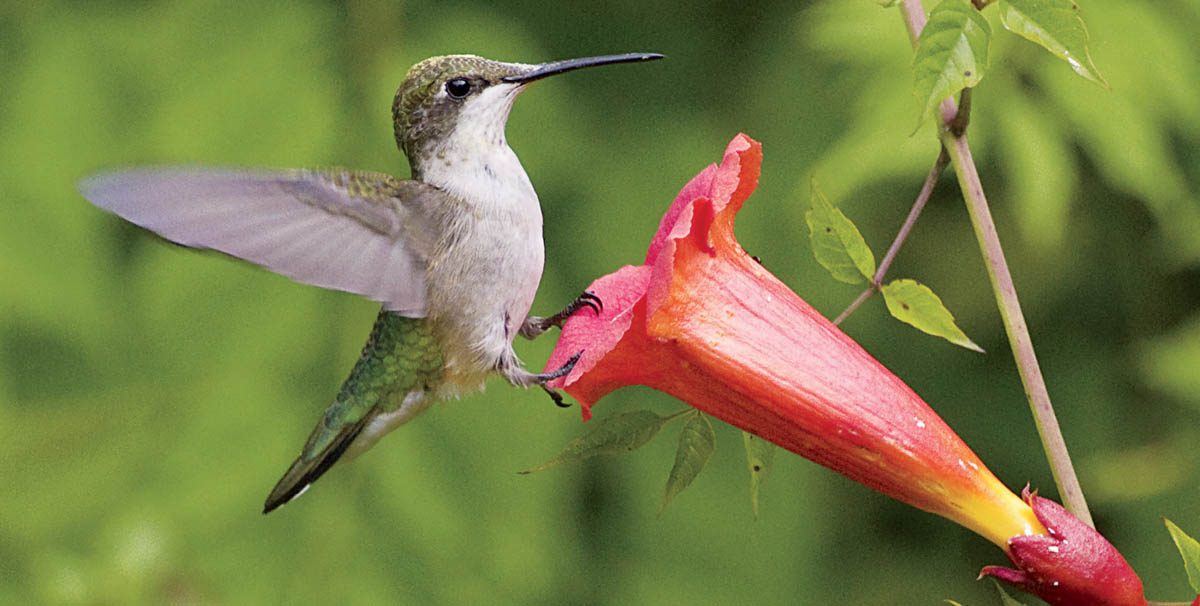

The hummingbird is a tiny dynamo. At rest, a Ruby-throated Hummingbird’s heart beats about 250 times every minute; this rises to 1,200 beats per minute in flight. Males chase other birds from hummingbird feeders, force competitors from flowers, and attack other species — even dive-bombing Bald Eagles, which weigh 1,600 times as much as they do.

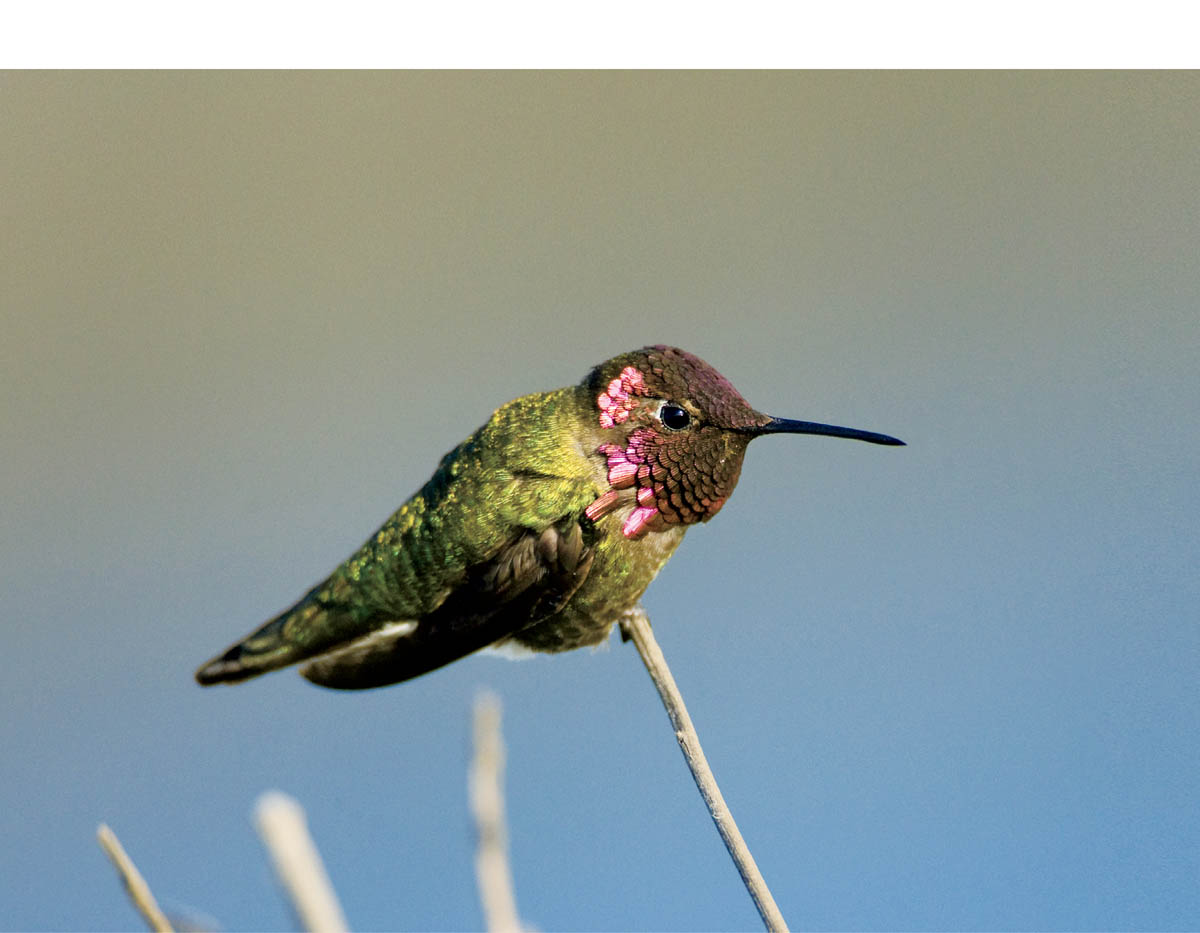

Anna’s Hummingbird male

Shown actual size, this Ruby-throated Hummingbird nest is made of plant down lashed together with spiderwebs (visible in lower right corner). The female shaped the nest with her body, smoothing the rim by pressing it between her neck and chest. She camouflaged the outside with lichens and moss.

A Ruby-throated Hummingbird female incubates her eggs. Notice how well this nest blends in with the supporting branch.

Hummingbirds are highly territorial during the breeding season, focusing around a food source. The male doesn’t form a pair bond with females drawn to his territory; he remains with each only for courtship and copulation, after which the females nest and raise the young themselves.

Despite the lack of a pair bond, females who happen to nest near a male’s territory may benefit from his presence. Female hummingbirds are larger than males, and when they flare the white patches in their tails, the males sometimes seem deferential, allowing them access to flowers that the male has been defending against other competitors. But females are perfectly competent to build the nest, incubate the eggs, and raise and feed the young without male assistance.

To entice females to mate, male hummingbirds perform conspicuous dive displays high in the air — soaring more than 100 feet, plunging toward the ground, pulling up and snapping their wings, singing buzzily all the time. They may repeat the entire display as many as 40 times in one bout. The female watches, and copulation often follows.

Feeders are an important food source for hummingbirds, especially at both ends of the breeding season. Even the best feeding station, however, will not entice hummingbirds to nest in your backyard. Two other elements seem most desirable: the presence of a sapsucker, and an abundance of spiders.

Sapsuckers are woodpeckers that drill holes in hardwood trees. In early spring, those holes well with sugary sap and attract insects, both essential food sources for hummingbirds arriving on their breeding grounds.

Although hummingbirds may snap up some tiny spiderlings ballooning through the air, the spiders’ main contribution is nesting materials. Hummingbirds construct their nest from bits of lichens, mosses, thistle and dandelion down, and sometimes pine resin, woven together with spider silk. The sticky gossamer binds the nest to the supporting branch and camouflaging vegetation.

Spider silk is also extraordinarily stretchy. The female needs tight quarters with thick insulation at first, to retain her body heat as she incubates her two tiny eggs and broods the tiny, naked nestlings. As they feather out, the nest must stretch to fit the chicks’ growing bodies. They’ll both be almost as large as their mother before they leave the nest!

To find the hidden nests of Ruby-throated and Rufous Hummingbirds, watch where females fly when they leave your feeder during the nesting season, and try to follow them. The female ruby-throat takes six to ten days to build the nest, usually on top of a branch 10 to 40 feet above ground; near human habitation, hummingbird nests have been found on loops of chain, wire, or electric cords.

The nests of Anna’s Hummingbirds are much easier to find, often built in areas of high human activity, probably due to their dependence on feeders and ornamental plants during the nesting season and to the high human population along the Pacific coast.

The incubation period for Ruby-throated Hummingbirds averages 13 days; it’s longer, about 16 days, for Rufous and Anna’s Hummingbirds. Female ruby-throats and rufous begin incubation when they lay the first egg, so it hatches a day or two before the second egg; some Anna’s delay incubation until the second egg is laid.

Nestlings hatch with very few feathers and eyes sealed shut. At first they huddle on the nest floor with virtually no activity between feeding bouts, but they lift their heads and open their mouths when the female arrives for feedings, and by the second or third day can back off the nest to poop.

The female feeds the nestlings a slurry of nectar, semi-digested tiny insects, and spiders via regurgitation, pumping gently and slowly at first but more vigorously as the chicks grow. At first, the mother broods the chicks most of the time, usually leaving only for feeding bouts, but as they feather out she spends less and less time warming them. When the nestlings are 15 to 16 days old, she starts bringing them small insects, holding them between her upper and lower bill. Insects provide a necessary source of protein while the young are growing.

Hatching. A newly hatched Ruby-throated Hummingbird nestles next to an egg that will hatch a day or two after the first. The tiny nestlings are altricial, naked and gray-skinned except for two thin tracts of yellowish white, hairlike feathers along their backs. The nestling’s eyes won’t open until it’s about nine days old.

Feeding. A female ruby-throat feeds a newly hatched nestling whose eyes are still closed. She will provide all parental care with no help from the male. She feeds by regurgitation, inserting her bill into that of the nestling. Notice how short the youngster’s bill is at this age; it will not reach full adult length until about 30 days after fledging.

7 to 9 days old. A Ruby-throated Hummingbird female feeds a nestling whose head bristles with pinfeathers. Its eyes are only just starting to open and its bill is lengthening. At this age, when the young birds’ feathers are finally developing, she broods them less and less.

Near fledging. One of two Ruby-throated Hummingbird nestlings tries out its wings while standing in the nest. The young birds start exercising their wings when about 15 days old, and the first chick leaves the nest when 18 to 22 days old. The younger one may remain for another day or two.

Anna’s and Ruby-throated Hummingbird nestlings fledge about 20 days after hatching. Rufous Hummingbirds fledge at 15 to 19 days, the faster progress probably a result of the longer daylight hours for foraging in the species’ northern breeding range.

When the first hummingbird in a nest fledges, it usually stays near the nest until its sibling fledges; together they depend on the female for another week or two. In summer, when two or three female/juvenile hummingbirds appear together at a feeder without squabbling, chances are they are a family.

At summer’s end ruby-throats, including those that hatched just months earlier, migrate on their own to the Yucatan Peninsula and then as far south as Costa Rica. For many, the flight path crosses the Gulf of Mexico, a treacherous, nonstop journey of more than 500 miles, during hurricane season; they make the same trip back the following spring. Ruby-throated Hummingbirds wearing U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service leg bands have survived more than nine years; those individuals made this arduous journey at least 18 times.

Adult male hummingbirds typically migrate ahead of adult females, which are still busy raising young. They migrate after their bodies have recuperated after their last brood fledges. The juveniles migrate last, already pugnacious and ready to face the big, wide world entirely on their own.

A fledgling Ruby-throated Hummingbird about 19 days old begs from its mother. When they first fledge, the young outweigh their mother, but even though she continues to feed them, they lose weight rapidly due to their sudden increase in activity before they have the skills to forage for themselves.

A juvenile Ruby-throated Hummingbird feeds from a trumpet vine flower in late summer.