Downy Woodpecker male

On the first days of January, when in northern latitudes the mercury has shrunk to the thermometer’s lowest depths, days are already growing longer. The worst of winter may be yet to come, but even on frigid mornings, we can hear a welcome sign of spring: the courtship drumming of a Hairy or Downy Woodpecker. Neither species will begin nesting until spring, but those rapid staccato beats are a promise of warmer days ahead.

Downy Woodpecker male

The louder a woodpecker’s drumming, the farther the sound carries, helping it defend a larger territory — and attract a potential mate from farther away. Woodpeckers usually have a favorite, particularly resonant drumming spot, such as a hollow snag or a bark-free area on a dead tree trunk, or another noisy surface such as a metal gutter, drainpipe, street sign, or utility pole.

Two Downy Woodpeckers perform a bill waving display. During territorial disputes, these woodpeckers hitch jerkily around tree trunks in pursuit of each other, fanning their tails and waving their bills, calling agitatedly.

Hairy and Downy Woodpeckers look bewilderingly alike, but they differ in size and, more helpfully, in bill length. The Hairy Woodpecker’s bill is almost as long as its head, while the bill on downies is noticeably shorter.

Not migratory, Hairy and Downy Woodpeckers tend to spend their lives in a relatively small area. Both species start drumming in mid-winter and seem to bond (or re-bond) with their mate at that time, but courtship doesn’t get serious until early spring. A Hairy Woodpecker male starts making a sputtering call, and when close to his mate, he erects the bright red feathers on his nape and spreads his white outer tail feathers. Courting downies perform butterfly flights, one following the other as they fly between the trees with slow, fluttering wing beats that resemble a flying butterfly.

A male Hairy Woodpecker raps emphatically and rhythmically with his bill. By late winter, both male and female Downy and Hairy Woodpeckers begin drumming to establish territories. A bark-free area on a dead trunk makes a particularly resonant drumming spot.

Often the female Downy Woodpecker chooses the nest site, but the pair usually investigates several likely spots together first. Hairy Woodpeckers begin nesting a week or two earlier than downies. In both species, the male and female take turns digging the nest, carving out the round entry hole to be just large enough for them to pass in and out. The finished cavity is slightly pear-shaped, 6 to 12 inches (15–30 cm) deep for downies, with a narrow entrance at the top. It typically takes about two to three weeks to excavate, but some birds can finish in just seven days.

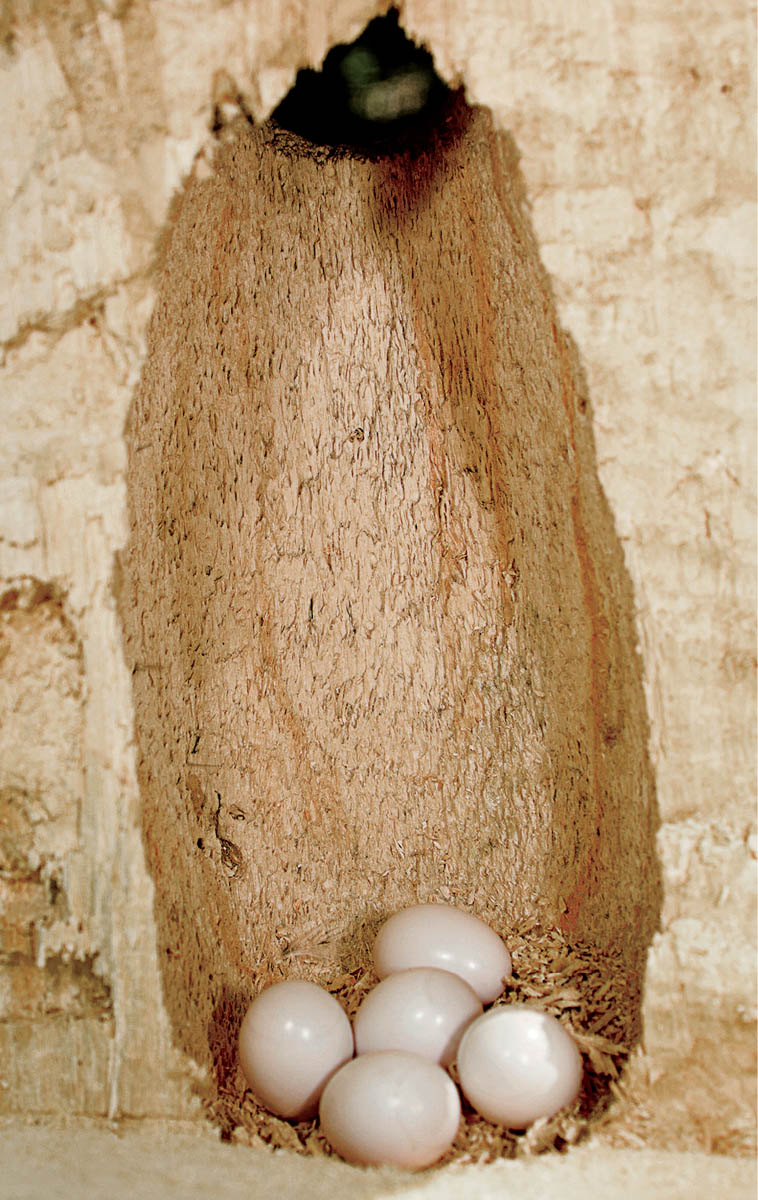

Both species lay an average of three to five shiny white eggs, laying them on the cavity floor without any additional nesting materials added. No camouflage is needed inside a cavity, and the shiny, white surface may help adults see them better in the dim light within.

Eggs. Woodpeckers (downies, in this sequence) do not line their nests but cushion the nest floor with a bed of woodchips. The eggs are glossy white and round, not pointed at one end. After about 12 days they hatch, usually at about the same time, but sometimes over a period of up to 48 hours.

Newly hatched. Woodpecker young are even less developed at hatching than other altricial species. Their thin skin is translucent, their skeleton and internal organs surprisingly visible through it. Their dark, still-closed eyes bulge from the skull. Adults drop the eggshells away from the nest.

1 week old. The female Downy Woodpecker reaches through the cavity entrance to feed her nestlings. Dark areas on their backs and crowns are tracts of feathers developing under the skin. Flight feathers on the wings have broken through the skin. Still enclosed in sheaths, they’re called pinfeathers. The nestlings’ eyes are just starting to open.

15–16 days old. The female brings a beakful of caterpillars to her nestlings. All four probably hatched on the same day, the less-developed two in back most likely third and fourth. Downy Woodpecker nestlings grow fast from the beginning, so a few hours’ head start gives the first-hatched a competitive edge.

A nest cavity protects eggs and nestlings from rain, wind, extreme temperatures, and predators better than an open-cup nest does, but it has disadvantages, too. During long bouts of incubation, carbon dioxide can build up to levels that would be dangerous for many birds. Fortunately, cavity nesters and their young are fairly well adapted to high CO2 levels, and to minimize the danger, the eggs hatch much sooner than eggs of most similar-sized species. As parents fly in and out, air exchange increases dramatically.

Few species other than woodpeckers excavate their own cavities, so even non-predators sometimes kill woodpeckers and their young to steal their cavities. House Sparrows and European Starlings are the worst culprits, but squirrels, mice, and some other birds will also occasionally take over an active woodpecker cavity. Hairy and Downy Woodpeckers build spare cavities to use as nighttime roosts throughout the year and backup nest holes when one is stolen.

Hairies often nest in living trees with fungal rot on the inside. They can hammer the entrance hole into wood too hard for squirrels to chew into, and then scoop out the rotted heartwood for the interior chamber. Aspens are ideal because they so quickly develop heart rot. Unfortunately, sapsuckers and flying squirrels also prefer aspens, and Hairy Woodpecker cavities are an ideal size for both these competitors. Hairies can more effectively exclude these species if they build their cavity beneath a curved limb.

Downies usually choose a dead branch on a dead or a living tree. Being larger, hairies more often use the trunk than a limb.

As with other woodpeckers, after the female lays the penultimate egg, both parents share incubation, the male taking night duty. The eggs hatch in only about 12 days. Woodpecker hatchlings are less well developed than hatchlings of other species, and utterly unfeathered, due to this short incubation.

The gape (open mouth) is thicker on woodpecker chicks than in most baby birds, broadened by pearly white to pinkish oral flanges that may give the parents a wider target in the darkness of the cavity. Though the nestlings’ eyes are sealed shut for a few days after hatching and not fully open for another week, the young birds can still discern the differences between dark and light. They start begging when a parent blocks the entrance hole, a signal that a feeding is nigh. By the second day, they can lift their heads to beg.

Woodpeckers provide critical ecological services to the animal communities around them. The cavities they excavate for roosting and nesting provide shelter for bluebirds, Great Crested Flycatchers, flying squirrels, and various tree frogs. By pecking into the wood to pull out insects for themselves, they open up access to the inner wood for smaller birds with weaker bills. In turn, both Hairy and Downy Woodpeckers benefit from associating with Pileated Woodpeckers; they can dig out insects from much deeper in the wood by working the holes made by the larger bird.

Hairy Woodpeckers hatch at close to the same time, and none get preferential feedings (see box). In contrast, first-hatched downies are fed large meals immediately after hatching, and may double their weight the first day. Even though all the eggs usually hatch that same day, the first nestling or two get a significant competitive edge. This developmental gap grows as the bigger nestlings continue to dominate their smaller siblings, begging more strongly and monopolizing the adults’ food deliveries.

This female Downy Woodpecker is carrying a fecal sac out of the nest. This sac’s surface has tiny fragments of wood from the nest floor stuck to it. Adults pick up the sturdy sacs and drop them at a distance to keep the nest clean.

A male Hairy Woodpecker feeds an almost full-grown female nestling at the cavity entrance.

Hairy Woodpeckers feed their nestlings about seven times per hour; Downy Woodpeckers about 11 or 12 times per hour. For the first several days, the parents take turns brooding the tiny nestlings almost constantly. As their eyes open and their feathers develop, the nestlings start literally climbing the walls and jockeying noisily for position at the nest hole.

Very young Hairy Woodpecker nestlings arrange themselves so that all get fed fairly equally. Facing one another in the center of the nest, each one drapes its long neck on a sibling, creating something of a circular stack. When parents arrive to feed them, the head of the chick that has waited the longest for a feeding will be at the top of the heap, and that chick will get fed first. After it takes a mouthful, it lowers its head, putting it at the bottom.

The parents feed whichever chick is at the top of the pile, but because of the chicks’ arrangement, they all tend to grow at the same rate and stay a similar size.

For two to three days before fledging, the nestlings take turns sitting in the entrance, begging constantly with raspy voices, watching for their parents to approach with food. Feeding is noisy and boisterous, and the young birds aggressively lunge at the adult. Gradually the adults return less often with food, enticing the chicks to start fledging. The first flight is usually brief; the fledgling lands on the nearest tree and remains motionless for much of the day. The adults feed it occasionally as they continue feeding the siblings still in the nest. Downy Woodpeckers fledge at about 18 to 21 days; Hairy Woodpeckers when about a month old.

The state bird of Alabama, the Northern Flicker spends a lot of time on the ground, but it’s a woodpecker through and through. The wing and tail feathers of birds from the eastern half of the continent have brilliant yellow shafts; those from the West have red shafts.

Northern Flicker (yellow-shafted) male

A flicker’s bright feather shafts (thick, central stems) serve as more than mere decorations; their brilliance may indicate a healthy diet and thus a bird’s fitness as a potential provider and protector. Interestingly, in areas where both red- and yellow-shafted birds live, birds don’t seem to prefer one color over the other, so hybridization is common. Bright wings and tail, along with the large white rump, are often flashed in territorial displays, and the colors may be more important for territorial defense than for attracting a mate.

In spring, flickers become territorial and start performing various behavior rituals. In the wicka dance, several flickers call flicking wings and tail and flaunting yellow or red feathers. The dancers may be two pairs squabbling over a nest tree, two same-sex flickers competing over a potential mate, or a pair selecting a nest site. When two flickers settle into a nest tree, they defend the space with loud, long-calling vocalizations, drumming, displays, and more dances and duels.

Flickers usually nest in open habitats with trees nearby, including open woodlands, forest edges, parks, and backyards. They are not strong excavators, so they select dead or diseased trees where decay has softened the wood and made it easier to dig. The nest is typically 6 to 15 feet off the ground but can be much higher. Both sexes share the work, the male usually taking the dominant role. Mating takes place on and off throughout the day, often on a nearby horizontal branch.

A territorial male flicker gives the long call, a long series of piercingly loud sounds, wik, wik, wik, wik…, from a tree stub above his nest site. Both male and female flickers call from prominent perches to establish territories and attract mates; they also both drum on wood or metal surfaces.

A pair of Northern Flickers copulates on a branch near their nest. Mating among birds is usually very brief and rarely observed. The female flicker solicits by crouching, leaning forward, and raising her tail slightly to expose her cloaca. The male hops onto her back, maneuvers his tail under hers, sometimes grasping the feathers on her head for balance, then briefly touches his cloaca to hers.

The female lays one egg per day. Flickers are a well-studied indeterminate layer: if one egg is removed each day, the female replaces it. (One female laid a total of 71 eggs!) If all the eggs are removed at once after incubation has started, it will take a week for her to begin laying again. This may happen more than once in a season, but not after early July.

As soon as a female starts incubating, ovulation stops. Both parents develop a large, oval brood patch and share incubation duties. They take turns during the day, but the male always takes the night shift, so incubates about two-thirds of the time.

Growing nestlings form a circle within the nest, facing outward, resting their chins and beaks upward on the nest wall. As they grow, their parents cannot fit into the cavity to brood them; soon they reach in only for feedings, regurgitating fairly large loads of insect mash with many ants.

When the nestlings are 18 to 19 days old, the tips of their bills are visible at the entrance. Their heads stick out at 21 days old. By now the feathers are developed and the breast spots obvious, and the parents no longer enter the cavity at all; they feed the chicks at the entrance hole. By the time the nestlings leave the nest at 24 to 27 days old, they look like small adults with slightly softer, duller plumage. We aren’t certain how long wild flickers remain with their parents in migratory populations, nor whether pairs remain together over the winter. Studies of marked birds show that when both birds of a pair return to the same area the following year, they usually re-establish their pair bond; “divorces” occur in about 25 percent of pairs.

Eggs. Like other woodpeckers, flickers deposit their eggs directly on the nest floor, with no nest material other than the woodchips left over from excavation. The nine eggs in this nest are an above-average clutch. Both adults incubate for 11 to 13 days.

Newly hatched. Nestlings lie in a heap on the cavity floor among fragments of eggshells. They have a white tip on the bill, the egg tooth, used to crack and then push out of the shell. The egg tooth disappears after a few days. Woodpecker nestlings are altricial, hatching bare and with their eyes closed, and require almost constant brooding at first.

4 days old. Five flicker nestlings reach up, begging and waving their tiny wing buds as the female feeds them. Their eyes are still closed, but the beginnings of feather tracts are visible as dark areas against the pink skin covering their wings, and one nestling shows the start of a tail.

8 days old. Feathers fluffed out, an adult male Northern Flicker squats over his nestlings, brooding them. The nestlings cannot regulate their own temperatures at first. A parent broods them almost constantly until their insulating feathers have grown in.

21 days old. Three flicker nestlings beg as their father regurgitates ants and ant larvae, some recognizable in his bill. Flicker nestlings peer out of the nest entrance and are fed there by the time they’re 16 to 21 days old, but won’t fledge until they are 24 to 27 days old, at which point they are fairly strong fliers.

Fledglings. Fledgling Northern Flickers wait to be fed. Researchers believe the fledglings become independent of their parents about two weeks after leaving the nest.