A diversity of eggs, clockwise from top left: Black-capped Chickadee, Killdeer, American Robin, Mallard

Every bird in the world, be it hummingbird or ostrich, penguin or condor, chickadee or turkey, has something in common: each emerged from an egg. And every one of those eggs started as a single-celled ovum (plural: ova) that popped out of the mother bird’s ovary at ovulation.

A diversity of eggs, clockwise from top left: Black-capped Chickadee, Killdeer, American Robin, Mallard

During most of the year, the sex organs of both male and female birds are excess baggage that would slow them down in flight, so except during breeding season, those organs shrink. Most female birds have one functional ovary which, during most of the year, resembles a tiny cluster of grapes. Each “grape” is an ovum, which may grow and develop, until by ovulation, it’s an entire yolk: a huge, single cell that, if fertilized by sperm present before or very soon after ovulation, will turn into a chick.

Eggs, like these of the Eastern Bluebird, look the same whether fertilized or not.

With birds, ovulation always leads to production of an entire egg, which exacts a heavy physical toll on females whether it’s fertilized or not. A female Ruddy Duck produces a clutch of eggs that, together, weigh more than she does. Unlike pet parakeets or domesticated chickens, wild birds can’t afford to ovulate even once without a strong likelihood that the egg will be fertilized and develop into a healthy chick. Human females may ovulate monthly for years before becoming pregnant, but most birds have physiological adaptations that prevent ovulation until:

Pairs usually start mating within days of the female’s first ovulation. Sperm remain viable inside her body for days or weeks even at high body temperatures, so if a female loses her mate after mating, she may still produce fertile eggs.

The song of the male Yellow Warbler helps trigger ovulation in the female.

When female hormones kick in at the start of the breeding season, stimulated by environmental and behavioral triggers, a few ova start swelling. Increasing day length during late winter and spring is the most universal trigger. But ovulation usually waits until stimulated by key behaviors such as displaying, song duetting, presenting and accepting nest materials to and from a mate, and building the nest.

Depending on the species, courting behaviors may stimulate both male and female hormonal levels and synchronize the pair physiologically. This ensures that females will be producing eggs precisely when males are producing sperm to fertilize them, after the nest is ready to lay them in.

Male hummingbirds are famous for not establishing a bond with their mates or visiting the nest and young, but they serve important functions that may contribute to the survival of their offspring. If a female nests near a strongly territorial male who tolerates her, he will chase other hummingbirds away from nectar-producing flowers but let her drink her fill, minimizing the time she spends off the nest.

Some male hummingbirds are so pugnacious that they dive-bomb Bald Eagles, but they often defer to females of their own species. These tiny birds are difficult to track individually by sight, so it’s not certain whether males are more deferential to their own mates than to other females, nor how likely it is that hummingbirds return to the same territories or mates year after year.

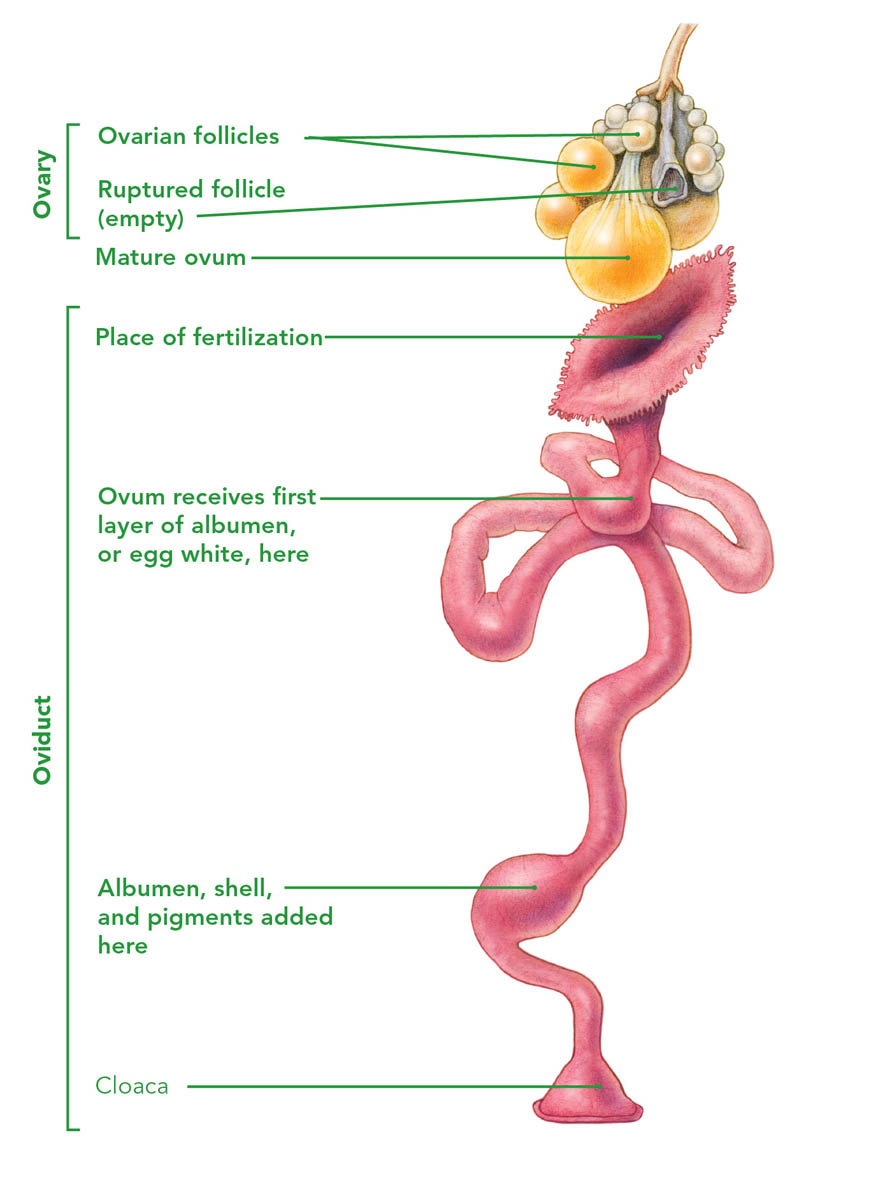

We refer to the ovum as the “egg” in mammals, but with birds this is confusing, because a bird’s egg includes much more than an ovum. If sperm reaches the upper part of the oviduct (the tubular passageway from the ovary to the outside of the body) as the ovum passes through, it may fertilize the egg.

Eggs of a Red-winged Blackbird

Fertilized or not, the ovum gradually makes its way along the oviduct, whose walls first secrete albumen (egg white) and then the minerals that form the shell. Finally the finished egg reaches the cloaca — an expandable, multipurpose chamber in both males and females that provides an entrance into the oviduct for sperm (in females), and an exit from the body for eggs (in females), sperm (in males), and droppings (in both). This process is the same whether the female has mated or not, and the eggs she lays look the same whether they’ve been fertilized or not.