IT’S ALL RELATIVE: FILIAL AND SIBLING CANNIBALISM

3rd Fisherman: I marvel how the fishes live in the sea.

1st Fisherman: Why, as men do a-land; the great ones eat up the little ones.

William Shakespeare, Pericles Act II, Sc. i

MANY INVERTEBRATES DO NOT recognise individuals of their own kind as anything more than food. As a result, a significant amount of cannibalism takes place within such groups as molluscs, insects and arachnids (spiders and scorpions). Clams, corals and thousands of other aquatic invertebrates have tiny, planktonic eggs and larvae, and these are often a major food source for the filter-feeding adults. Since the planktonic forms often belong to the same species as the adults feeding on them, by definition this makes filter-feeding a form of indiscriminate cannibalism.

Although both fertilised and unfertilised eggs are eaten by thousands of species, the practice of consuming conspecific eggs appears to have led to the evolution of an interesting take on the concept of the ‘kids’ meal’. Trophic eggs, for instance, are produced by some species of spiders, lady beetles and snails, and function solely as food. These often outnumber the fertilised eggs in a given clutch – a phenomenon exemplified by the rock snail. This species commonly lays around five hundred eggs at a time, but averages only sixteen hatchlings. The vast majority of the eggs are consumed.

In the black lace-weaver spider, this is only the beginning. One day after their young hatch, new mothers lay a clutch of trophic eggs, which they dole out to their hungry babies. The meal tides the young spiders over for three days, after which they’re ready for their next stage of development.

Arthropods – the phylum that includes spiders, insects and crabs – are characterised by having their skeletons outside their bodies. To grow in size, they undergo a regular series of moults during which their jointed cuticle or exoskeleton is shed and replaced by a new one arising from beneath the old. After their first moult, and after the trophic eggs have been consumed, young black lace-weaver spiders are too large for their mother to care for, though they are in dire need of additional food. In an extreme act of parental devotion, she calls them to her by drumming on their web and presses her body down into the gathering crowd. The ravenous offspring swarm over their mother’s body, then eat her alive, draining her bodily fluids and leaving behind a husk-like corpse.

Such a willing act of self-sacrifice is hardly the norm, however. Insects undergoing pupation, the quiescent stage of metamorphosis associated with the production of a chrysalis or cocoon, are particularly vulnerable to attack from younger peers. To counter this threat, the ravenous larva of the elephant mosquito not only consumes fellow pupae but also embarks on a killing frenzy, slaying but not eating anything unlucky enough to cross its path. The reason for this butchery appears to be the elimination of any and all potential predators before the larva enters the helpless pupal stage.

For some, cannibalism is only a juvenile phase. Certain snail species, for example, transform into vegetarian adults after a brief cannibalistic period. In one food preference test, hatchlings from a herbivorous species always chose conspecific eggs over lettuce, four-day-old individuals ate equal amounts of eggs and lettuce and sixteen-day-old individuals preferred the veggie option. When snails older than four weeks were denied the lettuce they starved to death, even in the presence of eggs. The reason for this gradual transition in feeding preference appears to be that these snails, like other herbivores from termites to cows, require a gut full of symbiotic bacteria before they can digest plant material. Since newly hatched snails have no gut bacteria, they’re compelled to consume easily digested material, even if this turns out to be their own unhatched siblings.

Cannibalism also occurs in every class of vertebrates, from fish to mammals. For researchers, factors like relatively larger body size and longer lifespans have made these backboned cannibals easier to study than invertebrates. As a result, previously unknown examples of cannibalistic behaviour are being revealed on an increasingly frequent basis. Additionally, factors related to the increased size and longevity of vertebrates have made it easier for scientists to determine and track kin relationships, leading to a greater understanding of the complexities of cannibalism-related behaviours. One such result has been the classification of cannibalism into distinct forms, such as filial cannibalism (eating one’s own offspring) and heterocannibalism (eating unrelated conspecifics), both of which have become vital to the concept of cannibalism as normal behaviour.

In most vertebrates, and specifically in mammals, filial cannibalism has been reported in rodents (like voles, mice and wood rats), in rabbits and their relatives, as well as shrews, moles, and hedgehogs. These mammal mothers sometimes eat their young to reduce litter size during periods when food is scarce and cannibalism also occurs in other circumstances, such as when litter size exceeds the number of available teats or when pups are deformed, weak or dead.

In stark contrast, for fish, by far the largest of the traditional vertebrate classes, individuals in every aquatic environment and at every developmental stage are ambushed, chased, snapped up and gulped down on a scale unseen in terrestrial vertebrates. One reason that cannibalism occurs so frequently may be the fact that the group as a whole has more in common with the invertebrates (where cannibalism is often the rule and not the exception) than do the other vertebrate classes (reptiles, birds and mammals). Another way to consider this is to think of fish as a mosaic – composed of a suite of more recently evolved vertebrate traits (like a spinal column and larger brain) but still retaining some invertebrate characteristics. Here it is the production of high numbers of tiny offspring with little parental care, as well as a proclivity for indiscriminately consuming both eggs and young, that predisposes them to filial cannibalism.

At its most extreme, reproductive success in many fish species depends on a romantic-sounding technique known as broadcast spawning, during which females can release millions of eggs, while males simultaneously release clouds of sperm (milt). The end result is that some of the eggs get fertilised. Each female produces between four and ten million eggs in a single spawning, though the record is held by the ocean sunfish, which can broadcast up to 300 million.

But it’s not just the abundance of eggs and young that makes fish such a popular menu item for members of their own species. Unlike most terrestrial vertebrates, which tend to produce few or single offspring of significant body size, most fish produce a huge number of extremely tiny young. This fact goes a long way towards explaining why the majority of them exhibit about as much individual recognition of their offspring as humans do for a handful of raisins. Fish eggs, larvae and fry are vast in number, minute in size and high in nutritional value. This makes them an abundant, non-threatening and easily collected food source. It’s also why experts consider the absence of cannibalism in fish, rather than its presence, to be the exception not the rule.

Parental care occurs in only around 20 per cent of the 420 families of bony fish (a group composed of nearly all living fish species except sharks and their flattened relatives the skates and rays). The primary logic underlying this trend is the fact that the natural world is full of trade-offs. Here, it works like this: since females expend a tremendous amount of energy producing huge numbers of eggs, they can’t afford to expend much energy caring for them or their young when they hatch. For this reason, the eggs and fry of most fish species exist in dangerous environments inhabited by a long list of potential predators.

Even in the ninety or so piscine families where parental care does occur, filial cannibalism is an extremely common practice, although it seems to depend on who is doing the babysitting. Among most land-dwelling vertebrates, females are the principal caregivers, while males take on support roles or simply make themselves scarce. In bony fish, though, it is often the males who guard the eggs, if they’re guarded at all. But the male guardians often end up consuming some of the eggs (partial filial cannibalism), and sometimes all of them (total filial cannibalism).

One reason they engage in this seemingly counterproductive behaviour may be that generally they have much less invested in the brood than the females. It is less costly to produce a cloud of sperm than it is to produce, carry and distribute an abdomen full of eggs. Furthermore, with their ability to search for food seriously constrained by caregiving duties, males are forced to undertake at least some degree of fasting. This practice decreases their overall physical condition and thus the likelihood of future reproductive success. By consuming a portion of the eggs, males can increase their own survival chances and therefore produce additional offspring.

In some instances though, unrelated conspecific males will raid nests in order to consume or steal eggs. Egg theft can be explained by the females’ preference to spawn at sites already containing eggs, even someone else’s. In these instances, once a female has been lured in to deposit her own clutch, the male will selectively eat the eggs he previously stole and deposited there.

On the topic of parental care in fish, mouthbrooding cichlids certainly deserve a mention. Mouthbrooding occurs in at least nine piscine families, most famously in the freshwater Cichlidae. With over 1,300 species, cichlids have evolved extremely specialised lifestyles (including mouth-brooding) that serve to reduce competition with related species living in the same area. Typically, mouthbrooding refers to post-spawning behaviour in which parents (usually females) hold their fertilised eggs inside their mouths until they hatch, and sometimes even beyond. This provides the eggs and fry with a haven from predators, a point commonly portrayed in nature videos that depict young fish darting back into their parents’ mouths at the first sign of danger. Less frequently reported is the fact that parents holding a mouthful of eggs usually eat a considerable portion of them, and sometimes the entire brood. Also unlikely to make it into family-friendly documentaries are shots showing the male cichlids’ habit of fertilising the eggs in the females’ mouth.

Mouthbrooders practise filial cannibalism primarily because, understandably, eating a regular meal is next to impossible while carrying around a mouthful of eggs. The simplest way around this vexing problem? Cannibalism. Interestingly, scientists had thought that for the first few days after spawning, female mouthbrooders selectively consumed only unfertilised eggs. When researchers set out to determine just how mothers were able to make the distinction, they were surprised to find that 15 per cent of the consumed eggs were actually fertile. And should the brood reach about 20 per cent of its original number, many mothers will simply eat them all. As with similar examples of total filial cannibalism, this usually occurs when the cost of caring for the young becomes higher than the benefit of producing a small number of offspring. In such cases, it becomes more advantageous for the female to recover some energy by consuming her remaining young and moving on to find a new mate.

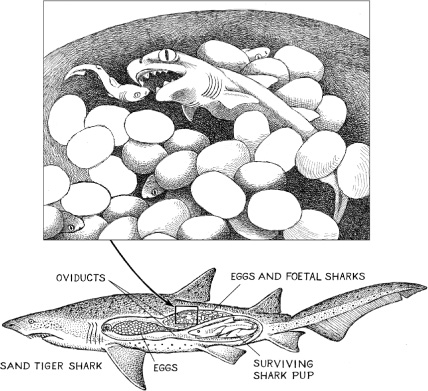

Perhaps the award for the most extreme example of piscine cannibalism, however, goes to sand tiger sharks. In their case the individuals doing the cannibalising haven’t even been born yet.

Sand tigers, like hammerheads and blue sharks, do not deposit their eggs into the external environment. Instead the eggs and young develop inside the females’ oviducts, a developmental strategy known as histotrophic viviparity. Scientists who first looked at late-term sand tiger embryos in 1948 noticed that these specimens were anatomically well developed, with a mouthful of sharp teeth – a point driven home when one researcher was bitten on the hand while probing the oviduct of a pregnant specimen. Strangely, these late-term embryos were found to have swollen bellies, which were initially thought be yolk sacs – a form of stored food. This was puzzling, though, since most of the nutrient-rich yolk should have been used up by this late stage of development. Further investigation showed that the abdominal bumps weren’t yolk sacs at all, they were stomachs full of smaller sharks. These embryos (averaging nineteen in number) had fallen victim to the ultimate in sibling rivalry – a form of in utero cannibalism known as adelphophagy (from the Ancient Greek for ‘brother eating’) or sibling cannibalism.

This is possible because sand tiger shark oviducts contain embryos at different developmental stages, a characteristic that also evolved in birds. Once the largest of the shark embryos run through their own food supply, they begin consuming other eggs. And when the eggs are gone, the ravenous foetal sharks begin consuming their smaller siblings. Ultimately, only two pups remain, one in each oviduct. According to renowned shark specialist Stewart Springer, the selective advantage for the young sharks may extend beyond the obvious nutritional reward.

Springer, the first to study the phenomenon, believed that the surviving pups were born ‘experienced young’, having already killed for survival even before their birth. He hypothesised that this form of sibling cannibalism might afford the young sand tigers a competitive advantage during interactions with other predatory species looking for a meal.

Although the sand tiger is the only species known to consume embryos in utero, several other sharks exhibit a form of oophagy, in which the unborn residents of the oviduct feed on a steady supply of unfertilised eggs. Additionally, a form of adelphophagy occurs in some bony fishes in which broods mature at different rates. Once again, in these species it’s the older siblings that cannibalise the younger.

Cannibalism of the young also occurs in many species of snakes, lizards and crocodilians, where, for example, it accounts for significant juvenile mortality in the American alligator. Although reptiles do not transition through larval stages like most fish and amphibians, the smallest and most defenceless individuals, namely eggs, neonates and juveniles, run the greatest risk of being eaten by their own.

Among birds, such behaviour is comparatively rare, a fact that may be related to one particular aspect of their anatomy – their beaks. These keratinous structures are responsible for the designation of most bird species as ‘gape-limited predators’. In other words, their lack of teeth limits them to consuming prey small enough to be swallowed whole. Existing under this anatomical constraint, when cannibalism does occur in birds it falls more under the general heading of filial cannibalism, where eggs and younger siblings are consumed.

Cornell ornithologist Walter Koenig informed me that brood reduction is common among birds, and so it’s likely that sibling cannibalism would be even more widespread if birds had beaks capable of tearing dying offspring to pieces, or could open their gapes wide enough to swallow them whole.

Heterocannibalism has been reported in seven of the 142 bird families and is most common in colonial seabirds. Here the practice of consuming eggs or young is an integral part of foraging strategy and it can have a significant effect on bird populations. In one study of a colony of 900 herring gulls, approximately one quarter of the eggs and chicks were cannibalised. This also occurs in acorn woodpeckers, as pairs of female woodpeckers will share a single nest and even feed and care for each other’s young. But before this occurs, the nest mates will destroy and consume each other’s eggs if one bird should lay first, presumably because the oldest hatchling would be the most likely to survive. To eliminate this advantage, the birds will keep eating each other’s eggs until both lay their eggs on the same day, a process that can take weeks.

Sibling cannibalism is best known among the raptors – predatory birds like eagles, hawks, kestrels and owls, all of which possess strong eyesight, powerful beaks and sharp talons. As a result they are far better equipped than other birds to engage in cannibalism. In some species, sibling cannibalism is the end result of asynchronous hatching, in which two eggs are laid with one of them hatching several days before the other. The firstborn chick uses its extra bulk to win squabbles over food, or in instances where the parents are unable to provide enough to eat, the firstborn will kill and consume its younger sibling. Researchers sometimes refer to these types of victims as ‘food caches’, as sibling cannibalism becomes an efficient way to produce well-nourished offspring (albeit fewer of them) during times of stress.

Something similar happens in the snowy egret. Three eggs are laid, the first two having received a serious dose of hormones while still in the mother’s body. The third egg receives only half the hormone boost, resulting in a less aggressive hatchling. If food is abundant the larger nestlings simply throw the passive chick out of the nest, but if alternative sources of nutrition become scarce, the smaller sibling is pecked to death and eaten.

According to Koenig and fellow ornithologist Mark Stanback, filial cannibalism in birds has been reported in thirteen of 142 avian families but it is not well understood, perhaps because it is still infrequently observed. On rare occasions, birds like roadrunners will eat undersized chicks. Similarly, barn owls are reported to consume their own chicks during extreme environmental conditions. It has been suggested that filial cannibalism of dying or decayed offspring can prevent infection and deterioration of the entire clutch. Presumably there are also benefits to getting rid of dead chicks before they attract legions of carrioneating flies and maggots. In most cases, however, it seems to be the lack of alternative forms of nutrition that initiates the behaviour.